Rewriting the climate story with young climate justice activists

Funding information: Funding for this study was provided by the University of Cincinnati’s Office of Research and the Society for Community Research and Action (American Psychological Association [APA] Division 27).

Abstract

Amidst intensifying climate breakdown and inadequate climate change education, young people are increasingly taking part in a global movement for climate justice. Young climate justice activists are disseminating stories of injustice and possibility intended to inform and activate their peers, parents, politicians, powerholders, and the public for sweeping systems-level change. Using in-depth interviews with 16 youth activists aged 15 to 17 from the United States, this study explored youths’ stories into activism, defined as the counterstories motivating youths’ initial and sustained engagement in the climate justice movement. Using reflexive thematic analysis, two interrelated thematic categories were generated: redefining the problem of climate breakdown and challenging dominant climate solutionism. First, activists spoke of questioning dominant, depoliticised discourses that regard climate change as a primarily scientific or environmental problem that adults are currently “solving” to prevent future harms. Youths’ counterstories emphasised that climate change is an issue of present-day and future injustices perpetuated by inadequate action by today’s adult leaders. Second, youths’ counterstories emphasised the powerful role of young people in spurring societal transformation towards climate justice—an inherently political and radical project requiring systems change through collective action. The research draws upon and contributes to recent scholarship in children’s geographies and critical geographies of education, while responding to urgent calls for reimagining climate pedagogies with young people’s well-being and political agency at the centre. By examining the counterstories employed by young activists, this research highlights storylines educators may mobilise to activate learners’ political imaginations and spur their active engagement in societal transformation.

Key insights

Youth climate justice activists are raising awareness of the unjust and inequitable impacts of the climate crisis while demanding that today’s power holders take urgent action to stop climate breakdown and radically transform present-day societal structures to make possible just, liveable futures. Drawing on in-depth interviews with activists, this study examined the counterstories that motivate and sustain youths’ activism. Youths’ counterstories served to redefine the problem and reframe solutions emphasising present-day impacts, climate in/justice, and young people as a powerful force for societal transformation. Findings have implications for developing alternative climate pedagogies capable of advancing youths’ well-being and political agency.

1 INTRODUCTION

School-age youth around the world are increasingly taking part in a global movement for climate justice (Bowman, 2020; Malafaia, 2022; Neas et al., 2022; Nissen et al., 2021; C. Walker, 2020). Climate justice is a concept and framework that blends sociospatial, sociopolitical, and socio-economic analyses to emphasise the disparate and inherently uneven distribution of climate-driven risks and harms, particularly between global North and global South contexts and between privileged and oppressed groups at more localised scales (Abimbola et al., 2021; Sealey-Huggins, 2017; Sultana, 2022a; Trott et al., 2022). Collectively, young activists are raising awareness of the unjust and inequitable impacts of the climate crisis, while demanding today’s power holders take urgent action to stop climate breakdown1 and radically transform present-day societal structures to make possible just, liveable futures in ways that prioritise the needs of marginalised groups (Foran et al., 2017; Holmberg & Alvinius, 2020; Thomas et al., 2019; Vamvalis, 2023).

Through activism, youth organisers are disseminating stories of injustice and possibility to inform and activate their peers, parents, politicians, power holders, and the public for sweeping systems-level change at local to global scales. Storytelling is a powerful tool for social change because stories help people interpret and articulate complex sociospatial phenomena, including the origins and impacts of environmental injustice (Bullard, 1993; Houston & Vasudevan, 2017). By providing interpretive frames, stories help to make sense of problems and why they are happening, who or what is responsible and/or at risk, and how to respond (Nisbet, 2009).

In formal education, the climate crisis is largely framed as a story of science, with environmental and technological storylines, yet little if any mention of its sociopolitical or justice dimensions (Neas, 2023; Trott, Lam, et al., 2023; Trott, 2024). This limitation applies not only to how the problem of climate change is storied in climate change education (CCE) but also to dominant solutions narratives emphasising “small steps” through individual behaviour change and “technology will save us” (Randall, 2009, p. 4). Consequently, CCE—particularly in the United States—faces criticism for perpetuating the neoliberal, modern/colonial status quo, even as education is so commonly invoked as a critical leverage point for societal transformation (Selby & Kagawa, 2010; Stein et al., 2023).

Given these important limitations of mainstream CCE, combined with the rise of the climate justice movement in providing alternative educative spaces for young people (Kraftl, 2014; Verlie & Flynn, 2022), critical questions for climate justice scholars include: What are the storylines that fuel young people’s engagement in climate justice activism? And how do these stories shape how they make sense of the problem of climate breakdown and its solutions? This study addresses these questions through in-depth interviews with youth climate justice activists from the United States. This research draws on recent scholarship in children’s geographies and critical geographies of education, while responding to urgent calls for alternative climate pedagogies capable of advancing young people’s well-being and political agency (Dickens, 2017; Dunlop et al., 2021; Neas, 2023; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; Verlie & Blom, 2022). By examining the counterstories employed by young climate justice activists, the study aims to shed light on storylines educators may mobilise to activate learners’ political imaginations and spur their active engagement in societal transformation.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS: COUNTERSTORYTELLING FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE

Narratives of crisis with ethical possibilities of redemption or a better future can challenge complacency, potentially assist to speed up adaptation, offer hope and bring other people on a collective journey to avoid the most disruptive aspects of anthropogenic climate change.

Through narratives that justify or question present-day realities, stories have world-making consequences. They are used to uphold or resist systems of power, oppression, and privilege. Jones et al. (2023, p. 2) emphasise this core function of storylines, defining them as “persuasive shorthand interpretation[s] of reality used to maintain and challenge dominant social orders.” Regarding environmental in/justice, storytelling can raise critical questions about science and policy discourses by attending to “the types of social realities they produce and for whom” (Houston & Vasudevan, 2017, p. 3). For instance, climate justice narratives stress that the uneven distribution of climate vulnerabilities is not “natural”—explained purely by biogeophysical forces—but instead is patterned in ways that reflect profound inequities built into societal structures to “suit some people’s interests at the direct and indirect expense of others” (Abimbola et al., 2021, p. 17; Sealey-Huggins, 2017).

Climate coloniality occurs where Eurocentric hegemony, neocolonialism, racial capitalism, uneven consumption, and military domination are co-constitutive of climate impacts experienced by variously racialized populations who are disproportionately made vulnerable and disposable.

As a counterstory that reframes the origins and impacts of the climate crisis, climate justice calls for solutions that “rectify social inequalities rather than embed them” (Thomas et al., 2019, p. 99). Specifically, according to Mikulewicz et al. (2023, p. 3), the dual aims of climate justice are (1) “to identify and foreground the needs of individuals and groups most marginalised in face of climate change impacts as well as our responses to these impacts (i.e. mitigation and adaptation strategies)” and (2) “to dismantle the individual and structural architectures of marginalisation, exploitation and oppression towards these groups.” In the youth climate justice movement, a central mobilising storyline concerns intergenerational in/justice, which emphasises the ways in which older generations primarily in the global North, by benefiting from fossil fuel extraction and failing to take action to avert climate catastrophe, have imposed present and impending dangers to younger and future generations, while excluding young people from formal spaces of present-day decision-making and action on climate (Newell et al., 2021).

3 DOMINANT NARRATIVES FOR YOUNG PEOPLE’S SOCIETAL EXCLUSION AND CLIMATE SOLUTIONISM IN EDUCATION

The commonplace exclusion of children and young people from spaces of formal decision-making on climate is rooted in adultism (Liebel, 2023), another world-making storyline that bifurcates youths’ and adults’ life experiences while subordinating youths’ perspectives and limiting their agency (Pasley & Jaramillo-Aristizabal, 2023). The concept of childhood is a Western construct generated alongside schooling for children (Ritchie & Phillips, 2021). Reinforcing the reductive segmentation of the human lifespan are dominant narratives that position young people as “learner citizens” or “citizens in waiting” who are neither invited nor considered capable of participating as active contributors in civil society (Phillips, 2010; Wyness, 2009). Especially in Western and neoliberal contexts, stories of idealised childhoods have positioned children as (1) vulnerable and in need of protection and (2) “free” from adult responsibilities given their role as learners and students (Ritchie & Phillips, 2021). Scholars of children’s geographies, education, and interdisciplinary childhood and youth studies have noted that these still-prevalent narratives of childhood serve to disempower children and youth, particularly in the context of climate change (Dunlop et al., 2021; Neas, 2023; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; Verlie & Blom, 2022).

Many mainstream pedagogies treat the [climate and nature emergency] as if it were a fairly recent and external disruption to an otherwise well-organized and optimal system. From this analysis, the current emergency is the result of technical problems that can be “solved” with expert knowledge so that we can return to “business as usual, but greener.” … By presuming entitlement to a future premised on the continuity of the present, many mainstream approaches to climate education imply the reproduction or even the expansion of multi-layered injustices.

By not discussing the magnitude or complexity of the problem, these mainstream CCE approaches may succeed in avoiding learners’ emotional discomfort in the short term. However, as young people inevitably encounter these realities beyond the classroom (Collins & Coleman, 2008), educators’ broken promises of “projective hope, simplistic solutions, and innocence” can leave students with a sense of overwhelm and betrayal over the longer term (Stein et al., 2023, p. 991). Indeed, studies have shown that young people, looking back on their CCE, report feeling underinformed or, given scientific but not solutions narratives, anxious and overwhelmed (Jones & Davison, 2021; Neas, 2023). As Neas (2023, p. 11) asserts, “the story told about climate change through education matters and matters deeply. This story becomes the framework through which young people understand climate change and shapes if and how they respond to it.”

4 YOUTH CLIMATE JUSTICE ACTIVISM AS AN EDUCATIVE AND EMPOWERING SPACE

Against the backdrop of intensifying climate breakdown and inadequate CCE, the youth climate justice movement has grown in size and visibility this decade. A core motivation for activism has been youths’ feelings of betrayal and abandonment by the adults in charge, due to climate inaction by political leaders (Hickman et al., 2021) as well as insufficient or non-existent CCE (Long & Henderson, 2023; Stein et al., 2023). Many youth activists are politically disenfranchised and thus are appealing to the adults in their lives to act on their behalf during this critical period referred to in the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022, p. 33) as a “rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

Given the aforementioned limitations of CCE, alternative educational spaces are key learning sites for young people (Collins & Coleman, 2008; Kraftl, 2014; Mayes, 2023)—particularly those created by the climate justice movement (Biswas, 2021; Crouzé et al., 2023). Learning within and through movement spaces has long been recognised by social movements scholars to be a powerful force for microlevel (psychosocial) to macrolevel (societal) transformation (Kluttz & Walter, 2018). Similarly, critical geographers of education have called attention to the sociospatial dimensions of educational practices, their implications for social justice, and the function of alternative education spaces that “attempt to subvert or avoid the educational mainstream” (Pini et al., 2017, p. 15). Through intentional confrontation and contrast with depoliticised storylines in mainstream CCE, the core messages of the youth climate justice movement deal directly with political, systemic, and justice implications of the climate crisis (McGregor & Christie, 2021). By telling new, more complex and critical stories of climate, youth activists grasp the world-making consequences of education and are in fact becoming educators themselves.

In their dissemination of storylines largely untold in school settings, youth activists are underrecognised as climate justice educators, yet their dedication to advancing climate justice awareness, advocacy, and action is clear. Indeed, the strategy of one of the largest networks of youth climate justice organisers in the United States—the Sunrise Movement (2023)—is to “build a movement of thousands of young organizers across race and class, [in order to] change the common sense that has led us to this broken world.” This prominent group has taken aim at local schools as spaces of transformation. Their bottom-up theory of change is “if we can remake our schools to take on the greatest crisis we’ve ever seen, we will pave the way for the rest of society to follow” (Sunrise Movement, 2023). In considering alternative education spaces and why they matter, prominent geographies of education scholar Kraftl (2014, p. 130) reminds us that, when considering the various scales at which education occurs, “the boundaries are porous and overlapping.” Indeed, by educating their peers, teachers, and school administrators about and for climate justice and sociopolitical action, youth activists are filling an important void created by deficient CCE, while flipping the script on unidirectional, adultist pedagogies that limit young people’s awareness, agency, and action (Biswas & Mattheis, 2022; White et al., 2022).

According to Stein et al. (2023, p. 988), the current state of CCE “does not serve our students, nor the communities who pay the highest price for the continuity of this system.” Thus, there is a need to develop alternative pedagogies that promote young people’s political agency and well-being while advancing climate justice (Neas, 2023; Verlie & Flynn, 2022). Youth activists are already doing this critical work within and beyond schools, so their experiences hold a wealth of insight for developing such pedagogies. Viewing school strikes as a “reckoning for education,” Verlie and Flynn (2022, p. 10) encourage scholars and educators to “take the political agency of young people seriously; and to allow ourselves to be influenced by, responsive to, and supportive of, young people, as we collectively work to cultivate climate-just worlds.”

5 THE PRESENT STUDY

The present research rests on the notion that those stories resonating with and told by today’s youth activists can point scholars and educators in promising new directions towards reimagining education for climate justice. Specifically, by exploring stories that draw youths into the movement and drive their continued engagement, this study aims to generate insight into critical climate pedagogies that respond to youths’ demands for school-based CCE that more accurately capture the realities of the intersecting and compounding crises we collectively face (Neas, 2023; Trott, 2024). Ultimately, by examining the counterstories endorsed and employed by youth climate justice activists, the present study aims to shed light on storylines educators may mobilise to activate learners’ political imaginations and spur their active engagement in societal transformation. Through in-depth interviews with youth climate justice activists, this study explored the questions (1): What are youths’ stories into climate justice activism and (2) how do these stories shape how young people make sense of the problem of climate breakdown and its solutions? In this study, youths’ stories into activism are defined as the (counter)stories motivating youths’ initial and sustained climate justice engagement, including the storylines that first piqued youths’ interest as well as those that fuelled youths’ deeper engagement with the climate justice movement.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

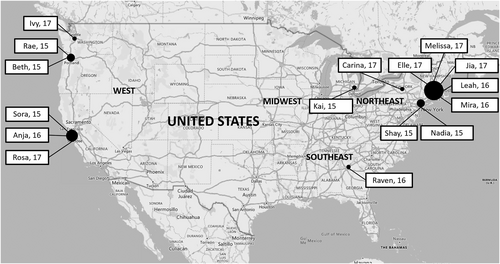

This research is part of a larger interview study exploring the views and experiences of 34 youth climate justice activists aged 15 to 25 in the United States. The present research focusses specifically on the 16 youngest participants in this study whose ages range from 15 to 17 years (M = 16.0; Table 1). Participants, assigned pseudonyms for this research, were from across the country (Figure 1) and were either in or recently graduated from high school. This age range was chosen for its temporal proximity to school-based CCE as well as the particular limits to political agency experienced by this group. In ways similar to young people in much of the Western world, youth under age 18 in the United States experience vastly different social, economic, and political responsibilities and rights compared with legal adults (Biswas, 2021; Holmberg & Alvinius, 2020). Notably, those under age 18 in the United States are legally considered sociopolitical “minors,” are unable to vote, and face numerous barriers to their political participation. Thus, the storylines that motivate and sustain teenage activists may differ in important ways from older youths, while having greater relevance to the project of reimagining climate pedagogies with young people’s agency and well-being in mind.

| Characteristic | Parameter | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15 years | 6 | 37.50 |

| 16 years | 4 | 25.00 | |

| 17 years | 6 | 37.50 | |

| Gender identity | Woman/female | 14 | 87.50 |

| Man/male | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Gender nonconforming/gender queer | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Races and ethnicities | Multiplea | 6 | 37.50 |

| White | 5 | 31.25 | |

| Black | 2 | 12.50 | |

| East Asian | 1 | 6.25 | |

| South Asian | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Educational level | 9th grade | 1 | 6.25 |

| 10th grade | 4 | 25.00 | |

| 11th grade | 5 | 31.25 | |

| 12th grade | 4 | 25.00 | |

| High school graduate | 2 | 12.50 | |

| Region | US Northeastb | 8 | 50.00 |

| US Westc | 6 | 37.50 | |

| US Midwest | 1 | 6.25 | |

| US Southeast | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Population | Urban | 8 | 50.00 |

| Suburban | 7 | 43.75 | |

| Rural | 1 | 6.25 |

- a Races and ethnicities represented = White (4), Jewish (2), Japanese (1), South Asian (1), Mexican (1), Indigenous (1), and Latina (1).

- b Subregions: Pacific Northwest (3) and Bay Area (3).

- c Subregions: Greater Boston area (5) and New York City and Upstate New York (3).

5.1.2 Data collection and analysis

Prior to data collection, this study was reviewed by the university’s ethics board. Then, following ethics clearances, voluntary participants were recruited online, primarily through emails sent to youth-led climate justice organisations and snowball sampling. Participation entailed completing an online sociodemographic survey to indicate their interest to be interviewed. All self-identified youth activists who expressed interest were contacted for an interview, and all those who responded were interviewed. In-depth, semistructured interviews were conducted over Zoom in the summer of 2021. The purpose of interviews was to understand youths’ lived experiences, motivations, and perspectives on being involved in climate justice activism. The interview script inquired about youths’ pathways into activism, what keeps them going, and how activism has impacted their relationships, outlook, and everyday life. A US$25 gift card was given for participation.

Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim and edited for accuracy prior to analysis. To address the study’s research questions, reflexive thematic analysis was used to identify and describe “the patterning of [shared] meaning across the dataset” (Braun & Clarke, 2022, p. 76). This process involved: (1) reviewing the transcripts to gain familiarity with the data; (2) generating initial codes to capture concepts of relevance to this study’s research questions; (3) iteratively clustering and organising codes to generate thematic categories; (4) revising thematic categories to “capture multiple facets of an idea or concept” (p. 80), with direct reference to the interview data; (5) defining each theme in narrative form and its relationship(s) to other themes; and (6) producing a written report of themes and their properties to “tell the story” generated from the dataset (p. 91). I completed coding initially on paper transcripts and then organised codes and thematic findings using digital files. To assist in the data analysis process, I wrote brief memos for each transcript to summarise notable features of each participant’s lived experience. In producing the report, I paid simultaneous attention to ensuring that selected quotes articulate themes, and that the voice of every youth activist is represented.

5.1.3 Positionality

The original aims of this study were to bring visibility to the critical work being done by youth climate justice activists and, over multiple phases, to conduct research in solidarity with youth activists as a way to move beyond the extractive nature of traditional research processes. As such, in conceptualising this study and conducting data analysis, the critical ideological lenses through which I engage with this research are aligned with many of those employed by youth activists. Nevertheless, I write from the limited perspective of a white, cis-gendered woman and professional academic in the United States holding many privileged identities, including race, social class, professional status, and nationality, which inevitably shape how I engage with the research. Moreover, my generational status as a Millennial differs from that of the youth activists in this study (Gen Z), whose lives and well-being are more acutely shaped by climate precarity (Holmberg & Alvinius, 2022). Additionally, as someone raised and residing in the Midwestern United States, characterised broadly by a conservative political climate, my life experiences differ in important ways from the majority of youths in this study who are situated in more politically liberal and progressive regions of the country. Still, I share with many activists Leftist political beliefs and a firm commitment to advancing climate justice through my life’s work. As noted by Braun and Clarke (2022, p. 11), “analysis happens at the intersection of the dataset, the context of the research, and researcher skill and locatedness.” No research is value-free, and my life experiences, past academic work, and political values and beliefs have undoubtedly shaped my approach to this research—from its conceptualisation to how I make sense of and report on youth activists’ views and experiences.

6 RESULTS

My research questions explore youths’ stories into climate justice activism—asking what motivated their initial and sustained engagement and how these stories shape the ways young activists make sense of the climate crisis and its solutions. Major thematic categories are phrased as storylines grouped into two main categories: (1) redefining the problem of climate breakdown and (2) challenging dominant solutions narratives for climate just futures. Pseudonyms, ages, and geographic regions accompany illustrative quotes.

6.1 Redefining the problem of climate breakdown

In describing their pathways into activism for climate justice, youths recounted experiences that allowed them to reframe climate breakdown in terms of its gravity, urgency, and justice dimensions and reimagine the role of young people as agents of change.

6.1.1 Climate change is affecting our lives and futures, and it’s way worse than we were told: storying the gravity of the problem

For a lot of people like myself, it’s just always been in the back of your mind that, “Oh yeah, the world’s gonna end someday. It’s gonna happen.” … It’s a fact of life type of thing. And then, I later realized, “Hold up. That’s concerning. That is bad. We should do something about that.” — Ivy (17, Pacific Northwest)

A big focus that initiated my start was IPCC reports and … learning about the hazards and the harms of global warming, and how it’ll really destroy our communities. — Leah (16, New England)

I live in Oregon, and one thing that is very, very important to a lot of the education here—public education specifically—is that we care for our environment. The majority of our state is forests, and it’s beautiful and I love it. … I went to a week-long, school-funded outdoor school where we … had a conversation one night about climate change and how, in hundreds of years from now, our planet … won’t be as pretty and there won’t be as much beautiful forest and land for us to live on safely. — Beth (15, Pacific Northwest)

I live in California, so we can experience the effects of drought and wildfires. The drought’s been going on since before I was born, too, so I think that’s also a big part of why I knew about climate change. But then recently, over the past few years, we’ve had really bad wildfires, and so I’ve actually experienced those, like the sky has gotten all orange and hazy and filled with ash and smoke. And then, our schools have actually shut down a couple of times, so I think that was also really monumental in shaping my personal experiences with climate change and making me care about it. — Anja (16, Bay Area)

6.1.2 The planet will survive, but people are suffering—and vulnerable groups suffer more: storying the injustices of the problem

The beginning of COVID worldwide has been a really interesting time because it magnified a lot of the disparities in racial ideology and economic ideology, hate crimes or eviction, and loss of healthcare for people in our country and globally, depending on where they live. Seeing the world topple around me really got me researching and thinking, and I guess I was like some scared 14-year-old at the time … Seeing just how unequal everything was below a looming climate crisis … pushed me to do some research to figure out the entire thing … I was like, “Well, I gotta do something.” — Kai (15, Midwest)

… issues like women’s rights and LGBTQ rights, and racial justice, and how that tied into the climate movement. That’s really what stood out to me [… the] focus on who’s really being impacted and who we need to uplift, and who needs to be central to the climate movement so that we can have a more equitable and just future. — Carina (17, East Coast)

Youths’ stories into climate justice activism often centred on the dual notion that the planet will survive but humans are suffering, and groups rendered vulnerable—including minoritised, racialised, and other marginalised groups—suffer disproportionate risks and harms, including those in the global South who have contributed the least to the climate crisis. As Rae (15, Pacific Northwest) put it, if we do not act, “the planet will technically survive, but humanity won’t survive … [Climate justice means] finding a way that we can co-exist with each other and also with the planet.”

6.1.3 Time is running out and the adults in charge are not acting fast enough: storying the urgency of the problem

I learned about climate change through the news … about the IPCC report that we only have, I think 12 years … before [the] effects of climate change were going to be irreversible. And just learning about the temperatures and just seeing wildfires and people have dirty water in Flint and nobody is doing anything about it, and people in other countries are literally killing themselves because … the soil that they used to plant food is not producing healthy food anymore … Just learning about that was really scary to think that we only had 12 years—and now it’s less than that, it’s probably like 10 or something. And then I knew that I had to do something. — Melissa (17, New England)

As young people, we are the ones who are gonna have to deal the most with the effects of climate change, and everyone’s very aware of that. And that’s one of the reasons why young people are so involved in climate activism … There’s that element, of like, “Okay, yeah, we can’t really trust the adults, we have to take things into our own hands.” And just general anger at the state of the world. — Mira (16, New England)

6.2 Challenging dominant solutions narratives for climate just futures

Youths’ pathways into climate justice activism encompassed developing counternarratives to hegemonic solutions scenarios disseminated in school and society. Envisioning and enacting just climate futures, participants emphasised the need for collective action for systemic change to advance climate justice and a powerful youth-led movement to spur societal transformation.

6.2.1 Individual action is not enough; collective, justice-driven action is needed for systemic change: challenging dominant climate solutionism.

When I think of climate justice, I also think of dismantling the systems of oppression that have brought us here, and no more economically exploiting poor people, and people of colour, and the planet … I think that all teachers have an obligation to teach that climate justice is not just about the science and about the planet’s climate, and it has a lot to do with people and the way that people interact with each other … It’s really important that teachers do the work to teach their students about all this ‘cause … I had to kind of learn about what the climate justice movement was on my own. — Rosa (17, Bay Area)

A lot of people make it seem like it’s like the people’s fault that we’re facing the consequences [of climate change], “Oh, because you’re not using metal straws … because you don’t have an electric car,” basically blaming poor people for the climate crisis, people who can’t afford all of these things. When learning about climate justice, I realized that … the same system that perpetuates … blaming it on poor people … started the climate crisis and all of the other crises that we’re facing. So, I’m talking about white supremacy, colonialism, capitalism, all really big things that are the reason for facing the climate crisis … Through climate justice, I learned that it’s not the people’s fault. It’s more like the systems that allow people to be treated the way that they’re treated. — Rosa (17, Bay Area)

Climate justice … [is] the intersection between environmental change and social change … [that] is gonna disproportionately affect minorities and people of colour, and that for us to stop climate change, we also need a whole lot of system change … [So] it’s really important … that we take it to a political level, which is also what climate justice is about. — Sora (15, Bay Area)

I’m not an expert on education in any way, but I think the important parts are telling people the truth, because the truth is climate change is going to have a large impact on their lives. It’s going to be probably the most impactful crisis in their life. And they need to know that because they need to know that they have the power to change that, and because it’s their life … it’s their future, and they need to have a say in it. And so, education can be how they learn about how they can make their voice heard. It’s important to teach them the truth, and teach them they have a voice and they can do something about it. — Carina (17, East Coast)

6.2.2 Young people are powerful, especially when we work together: challenging dominant theories of change for societal transformation

I didn’t think [climate change] was something I could control until I started hearing more about Sunrise … and their messaging about “young people can take the power in their hands and pressure their elected officials” and that young people … have more power over climate policy than we thought we would, rather than just “climate change is something [that is] inevitable.” — Elle (17, New England)

My middle school was right next to a really busy freeway, and I had a teacher who got my classmates and I involved in air quality work around the school … This teacher got us involved in lobbying for some legislation that would regulate diesel emissions in Oregon … [We went] to the Capitol and talk to our legislators, and that was the first experience where I really realized I could make a difference as a kid … [My activism came from] a combination of being directly impacted by a climate issue, but then also seeing other people in my life start to take action, and having that teacher who was there to tell us like, “You guys have power and people will listen to you,” was really impactful, and I wish more kids had that. And I’m also constantly inspired to keep going by seeing other young people around me who are taking action. — Rae (15, Pacific Northwest)

I think the biggest challenge I face is just not being taken seriously. I’ve met with a lot of adults and elected officials and … they seem to want to do it themselves or not totally take your ideas into consideration … Just because you’re young and because you don’t have experience in politics or government, they don’t want to value your ideas as much as they would take an adult’s … And I’m not really sure why, honestly, anymore ‘cause kids have proven over and over again now that they are just as capable as adults. This generation is a lot more interested in policy and politics and government than previous generations, and that that is something elected officials and adults and really anyone who isn’t a youth should be paying attention to and helping youth express their ideas and take part in our democracy … even if we don’t have a vote or a say, really. — Nadia (15, East Coast)

I think most people, whether or not they’re involved in climate justice are somewhat worried about our future. I don’t know if there’s any way you can’t be. But by funnelling … our fears into something productive, I think that’s really helpful. And that’s why a lot of people join climate justice organizations. — Anja (16, Bay Area)

It’s definitely made me feel like I can have more of an impact … and young people can have more of an impact … Just the fact that we are able to … be a legitimate organization even though we’re run by young people, always gets me excited … I’d definitely say it’s made me more hopeful. — Elle (17, New England)

7 DISCUSSION

This study has explored youths’ stories into climate justice activism, defined as the (counter)stories motivating their initial and sustained sociopolitical engagement. This research responds to the need for “the creation of new educational narratives [through which] we can begin to envision and enact transformational change in the face of climate disasters” (McKenzie et al., 2023, p. 6). For the young activists in this study, becoming involved in activism was, first, a matter of reframing the problem away from dominant discourses that regard climate change as a primarily scientific or environmental issue that adults are working on in order to prevent future harms. Youths’ counterstories emphasised inadequate action on the part of today’s leaders as well as present-day impacts—and impending irreversible climate breakdown—that disproportionately affect minoritised and marginalised groups in the United States and around the world. Youths’ interest and sustained engagement in climate justice activism also required reimagining climate solutions that follow from their alternative problem definitions. To them, advancing climate justice—an inherently political and radical project in the service of (more-than-)human flourishing—requires dismantling oppressive systems through collective action and that young people can be a powerful force for societal transformation. These central stories have key implications for those committed to just climate futures through alternative approaches to education. In what follows, findings are discussed through the lens of “classic story structure,” which consists of the setup, inciting incident, rising action, climax, and resolution (Caldwell, 2013, p. 1).

7.1 “Inciting incidents” activating youths’ critical climate justice awareness

Among the most common definitions of a story is “something with a beginning, a middle, and end” (Moezzi et al., 2017). The beginning, or exposition, sets the scene, which is interrupted by an inciting incident—a turning point—that commences the story’s middle. In this study, young activists told of being disengaged from the issue of climate breakdown before being awakened to its unsettling realities primarily through their engagement with alternative educational spaces beyond school settings (Kraftl, 2014). An inciting incident is typically “an unexpected event, a catalyst that begins the story action” (Caldwell, 2013, p. 5). Youths’ exposure to the dire realities of the climate crisis—often through news, social media, and (coverage of) climate justice activism—set many on a course of action to inform themselves about the problem through independent (online) research, conversations, and engagement with local groups. From this position, youth activists came to understand climate change more deeply as happening now, affecting their lives and futures, and as a matter of multifaceted injustices perpetrated against and disproportionately affecting groups made vulnerable by societal conditions ranging from marginalisation to exploitation and disenfranchisement.

In storytelling, inciting incidents operate to draw contrast between the “ordinary world” and a “different world” (Caldwell, 2013, p. 9). Indeed, young activists came to “recognize a growing gap between the world their education was designed to prepare them for, and the world they will inherit” (Stein et al., 2023, p. 988). By accessing alternative sources of information beyond school walls (Collins & Coleman, 2008), youths gained a deeper awareness of the necessity for urgent action by today’s leaders and, emboldened by the powerful messages and images of youth-led movements, saw a role for themselves in bringing necessary change. In sum, youths’ stories into activism pointed to a range of inciting incidents characterised by gaining critical awareness of the intersections between climate breakdown, injustice, and youth-led action.

Prior to these inciting incidents, participants described a range of settings that reflect findings of previous research, principally that traditional approaches to CCE had done little to inform them of the gravity and injustices of the climate emergency (Neas, 2023; Trott, Lam, et al., 2023). In this and previous studies (Bhattacharya et al., 2021; Jorgenson et al., 2019; Monroe et al., 2019), the abstract, depoliticised, and science-centric framings common in school-based CCE left young people feeling disconnected from the issue and ways of addressing it. The pivotal turning point was exposure to counterstories emanating from the climate justice movement that began to disrupt “the patterns of thinking, feeling, being, and relating that are encouraged, naturalised, and rewarded within modern/colonial educational paradigms” (Stein et al., 2023, p. 994). These new storylines instigated youths’ sense of responsibility and urgency for sweeping policy action and systems change, particularly in light of their awareness of impending irreversible climate destabilisation. As in previous research, youth activists emphasised the lack of adequate action by today’s leaders, which gave rise to action-inducing feelings of outrage, abandonment, and institutional betrayal (Barnwell & Wood, 2022; Han & Ahn, 2020; Hickman et al., 2021). Joining the climate justice movement, for many, was inspired by the combination of their newfound critical awareness plus seeing examples of young people using their voices to demand action for just climate futures. In the United States and elsewhere, young people are steeped in dominant societal messages that seek to limit their political agency (Holmberg & Alvinius, 2020; Lam & Trott, 2024). In this study, young activists eschewed these restrictive storylines to claim their role as critical messengers and change-makers in society. Through exposure to justice-centred counterstories of climate breakdown, they entered an unfamiliar world in which environmental signals prompted wholly new and different directions for action—a world in which youths became climate justice educators themselves.

[Climate] education otherwise [that] encourages us to situate hope in the quality and integrity of an ongoing practice of expanding our capacity to face and process difficult intellectual, affective, and relational challenges in the imperfect present. It also asks us to take into account the past and how it has shaped the social and ecological injustices that have accumulated and become sedimented within the present.

As this study demonstrates, becoming aware of, and incensed by, climate injustice can be a pathway towards youths’ deeper connection and engagement with the issue, while the positive energy of the youth climate justice movement can be a critical source of positive emotions—inspiration, hope, and connection (Arnot et al., 2023; Elsen & Ord, 2021; Vamvalis, 2023). With young people’s sense of agency and emotional geographies in mind (Kraftl, 2013), creating alternative climate pedagogies for the classroom requires balancing narratives of injustice with youths’ critical reflection, un/learning, and action for societal transformation.

7.2 “Rising action” enabling youths’ political agency for just climate futures

Returning to classic story structure, rising action refers to a series of turning points, or revelations, which follow inciting incident(s) and propel the story forward (Caldwell, 2013, p. 3). In this study, once youth activists became aware of the grave, unjust realities of climate breakdown and inadequate action on the part of today’s leaders, they adopted and deployed counterstories from the movement emphasising solutions that enable just climate futures. These narratives ran counter to dominant discourses of climate action they learned in school and society that endorsed individual action, environmental protection, and adult leadership (Randall, 2009). Echoing findings of previous research, many young activists reported their school-based CCE focussed solely on the problem, not solutions, and left them feeling powerless (Jones & Davison, 2021; Neas, 2023). Moreover, they explained that CCE-driven action opportunities, with few exceptions, were either entirely absent or focussed on personal lifestyles and behaviour modification. Towards resisting climate solutionism—uncritical, neoliberal narratives of climate solutions—youths’ counterstories centred on the need for action-focussed climate justice education, collective action for systemic change, and the key role of youth-led movements in societal transformation (Trott, 2024).

This study’s findings reflect previous research documenting that most CCE either lacks an action focus or encourages individualised modes of action focussed on daily habits and minimising one’s own carbon footprint (Monroe et al., 2019; Neas, 2023; Waldron et al., 2019). Youths saw value in living eco-conscious lifestyles but—drawing on justice-focussed counterstories—felt it was misleading when framed as the solution to climate breakdown (Schindel Dimick, 2015). Rather, what is needed, they asserted, is collective action for systemic change. Youths’ conceptions of climate justice, in this study, were consistent with published theoretical and empirical research on the topic (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Trott, Gray, et al., 2023; C. Walker, 2020). They emphasised the point that the people least responsible for climate breakdown are bearing its heaviest burdens across local to global scales (G. Walker, 2009). In line with critical climate justice scholarship (Sultana, 2022a, 2022b), youths’ counterstories highlighted the systemic roots of the climate crisis in white supremacy, capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism. Through counterstories they encountered in the movement, advancing climate justice became a matter of dismantling these entrenched systems of domination, exploitation, and extraction that simultaneously fuel climate breakdown and perpetuate widespread suffering. Doing so, they noted, is an enormous task requiring mass mobilisation and collective action to demand structural and policy change. Perhaps, the most influential solutions-focussed counterstory for youth activists was that a key contingent in the monumental struggle for just climate futures is the world’s young people who can be a powerful force for social change. For many, what prompted and sustained their engagement in climate justice activism was feeling a part of a wider movement of young people collectively taking action and using their voices to demand change (Arnot et al., 2023; Elsen & Ord, 2021; MacKay et al., 2020).

Climate education otherwise supports young people to develop the stamina and the intellectual, affective, and relational capacities that will enable them to respond to the [climate and nature emergency] and other social and ecological challenges with justice-oriented coordinated action that is appropriate and relevant to each context they will face.

Fortunately, envisioning preferable futures can activate learners’ positive emotions (Finnegan, 2022) while simultaneously cultivating their capacity to imagine radical alternatives beyond the entrenched systems that presently shape their lives, limit their agency, and threaten their futures.

The particulars of how climate justice pedagogies are envisioned and enacted will inevitably be shaped by contextual features that facilitate or impede new possibilities (McGregor et al., 2018; Panos & Sherry, 2023). Just as “school life for young people is connected to life outside,” noted Dunlop et al. (2021, p. 292), “relations and processes in schools are dependent on the surrounding society.” These include the histories, geographies, and sociocultural and political landscapes upon which this creative experimentation takes place. In this study, youths’ counterstories were informed by their connection to place, including their direct experiences of climate injustice and climate-fuelled extreme weather and disasters as well as the politically favourable to politically hostile US contexts within which they were embedded. Moreover, youths’ counterstories shaped how they understood the places and spaces they inhabit and how and why they must be transformed. These and other important factors will undoubtedly influence students’ needs and desires in classroom contexts, adding emphasis to calls for place-based, creative, and participatory approaches that support youths’ agency and well-being (Grewal et al., 2022; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; C. Walker & Vance, 2023).

7.3 Limitations and future directions

Findings should be interpreted in light of this study’s limitations. First, most participants were located in and around some of the most politically progressive cities and regions in the United States, meaning that the voices of youth activists in politically conservative and rural locales are limited in this study. New research should explore youths’ pathways into and experiences of climate justice activism in less politically advantageous areas and the unique barriers faced by youths in these contexts. As Feldman (2022, p. 116) noted, “climate change effects [sic] all young people, regardless of their location, socio-economic status or cultural background,” yet research is dominated by particular forms of activism in particular regions, such as global North protests. Second, although the stories of youth activists can be pedagogically informative, we cannot expect all young people to have the willingness, ability, and contextual affordances to act on climate (Barnes, 2021; Feldman, 2021; Nkrumah, 2021; Prendergast et al., 2021; C. Walker, 2020). Young people respond to and cope with critical climate awareness in a range of psychologically protective ways (Hickman et al., 2021; Ojala, 2012), and sociopolitical engagement—despite being a constructive outlet for some, as this study showed—cannot be prescribed (and indeed is often proscribed in CCE). Rather, towards affirming youth agency through alternative climate pedagogies, learners should be encouraged to explore and experiment with modes of engagement that fit their specific needs (Marks et al., 2023; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; Trott, Weinberg, et al., 2023). More research is recommended that explores how young people with differing levels of prior knowledge interpret, engage with, and act for climate justice when provided a range of creative, participatory avenues for deeper engagement as well as the psychosocial and contextual barriers youths face.

8 CONCLUSION

The present research responds to the need to “radically reimagine climate pedagogies” (Neas, 2023, p. 12) with young people’s well-being, radical imaginaries, and political agency in mind. To find pedagogical inspiration and wisdom for how to transform critical climate awareness into impassioned collective action, it is important to look to young people who have made this “critical turn” (Neas, 2023, p. 13) and learn from the stories that guide, inspire, and sustain them (Bowman, 2019; Malafaia et al., 2022). The young people in this study became climate justice activists despite—and, at times, in response to—the inadequate, misleading, and sometimes disempowering messages they received in the classroom. The counterstories that sparked youths’ initial involvement and fuelled their sustained engagement were those that redefined the problem of climate change as one of present-day and worsening injustice as well as storylines that reimagined solutions through youth-led collective action for systems change.

Whether learned in school or elsewhere, young people are increasingly aware of the multifaceted injustices of the climate crisis, and many are taking action to ensure a liveable and sustainable future for all. To meet young people where they are and begin to repair a facet of the institutional betrayal they rightly feel, schools should be a key site for apprehending and acting on today’s realities through generative dialogue and democratic engagement. In this pressing moment—for our purposes, the story’s middle, with action rising in response to ever-intensifying climate breakdown—this means cultivating youths’ critical awareness, political agency, and collective action towards ensuring just climate futures.

Stories end with a climax and resolution, an inflection point followed by a new reality. Whether sweeping global action is taken today or climate breakdown proceeds unabated, another world is not just possible but guaranteed. Young activists are working hard to change the story’s ending from “an apocalyptic crescendo delivering the world to a point of no return” to “a collective reckoning gives way to a new and better world.” On this difficult journey that we have no choice but to be on together, scholars and educators would do well to heed the complex warnings and infinite possibilities embedded in the counterstories emanating from the youth climate justice movement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the youth climate justice activists who took part in this study and the Collaborative Sustainability Lab research assistants who contributed to data collection for this study: Emmanuel-Sathya Gray, Stephanie Lam, Jessica Roncker, and R. Hayden Courtney.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The research undertaken in this article was reviewed by the University of Cincinnati’s Institutional Review Board prior to data collection and fully complies with the university’s ethical standards.

ENDNOTE

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.