Reimagining urban design of stormwater infrastructure in settler-colonial Sydney

Abstract

Although many might consider the Australian city of Sydney as defined by golden beaches and a glittering harbour, the city actually has an abundance of wetlands—swamps and marshes laid out across the eastern Sydney region. Dramatic transformations of these waterscapes have taken place since 1788, when British colonists landed to form the settlement there. Environmental exploitation has been a key part of settler-colonial projects across the world. Sydney is no different. To contextualise this exploitation, I explore the ways in which a specific water infrastructure system in Sydney—the Tank Stream—has been entangled with, and is emblematic of, settler-colonial politics. I argue that to reimagine futures where such ecologically and culturally damaging infrastructures no longer have a presence in the city requires a nuanced interpretation of both water and history. I suggest that “conventional” stormwater design features emerged from colonial viewings of Sydney’s waterscapes. The transformation of these geographies was imposed on existing water management systems, set within local, First Nations knowledges. Thus, I also consider the Tank Stream as a site with potential to present an anti-colonial hydraulic urban co-design framing. I draw on colonial archival material and field site visits to question the importance that settler-colonial urban design has had in shaping contemporary ways of thinking about watery spaces. I conclude by arguing that the hydro-imperial knowledges must make way for a culturally inclusive urban water design that centres and elevates First Nations design.

Key insights

The historical geography of cities such as Sydney is heavily shaped by settler-colonial influences. Using water as a conduit to consider how urban infrastructures such as drainage evolve, I argue that hydro-imperial knowledges must make way for culturally inclusive urban water designs. Work being done by First Nations designers, planners, and architects is paving the way for cities to be designed on the principles of ecological balance and socio-environmental justice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sydney’s watery spaces are diverse and wide-reaching. From the harbours, bays, rivers, and estuaries to the creeks, swamps, drains, and ponds, the city is soddened with wet geographies. To unpack the complex histories and contested urban politics that these spaces possess, this article presents a reflection on how urban stormwater infrastructures—a hydraulic urban design—are situated against a growing movement of First Nations-led co-design practices. From this foundation, the core argument asserts that reimagining Sydney’s urban stormwater infrastructures should be working from an anti-colonial hydraulic urban co-design framing. That work proceeds by presenting two core concepts: “hydrontopower,” or the ways in which waters are known and experienced, reflects uneven power relations; and “kinfrastructure,” an acknowledgement of how designed and created infrastructures that have become habitats and living systems themselves might be considered as kin and thus necessitate structures of responsibility, duty, and care. The article advances these concepts in three parts: section 2 locates the argument within the literature on interdisciplinary water studies; section 3 discusses how hydro-imperial design still shapes urban waterscapes today; and section 4 presents a speculative imagining of alternative urban water infrastructures based on First Nations knowledges and design principles. Insights are captured in the conclusion in section 5.

2 WATERING HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIES, HISTORICISING WATERY GEOGRAPHIES

Analysing the underlying politics of Sydney’s water infrastructures requires a substantial historical reflection. Much has been written on the histories of Sydney’s waterways: Sydney Cove and surrounds (Karskens, 2009; Rogers, 2022); the Cooks River (Tyrrell, 2018); the Georges River (Coyne et al., 2020; Goodall, 2021; Goodall & Cadzow, 2009); the Dyarubbin/Hawkesbury-Nepean (Karskens, 2021); and Sydney Harbour (Irish, 2017). Across these texts, there is a focus on how British settlers interacted with the region’s First Nations peoples and on what implications those interactions had on both environmental histories and, more broadly, the wider histories that were to emerge. Indeed, within much of the literature on Sydney’s water histories, the threading together of environmental and “non-environmental history” is quite tight. As Griffiths (2007, n.p.) notes, “Nature is stage and setting for the human drama, and it is also something that humans do things to. Nature is changed—made historic—by human action.” Working with this enmeshed notion of “nature”—as a complex, metabolic socionature (Swyngedouw, 1996, 1999)—guides my core argument: to understand how water infrastructures associated with the settler-colonial project have been politicised, a nuanced interpretation of both water and history is required—a hydrosocial history (Linton, 2013; Morgan, 2017; Schmidt, 2014).

Leading this interpretation is the notion of connecting water and colonialism—most succinctly articulated by Pritchard’s (2012) concept of hydro-imperialism, Hofmeyr’s (2022) hydro-colonialism, and works by Gibbs (2009) and Hartwig et al. (2022). These terms refer, mostly, to a “colonisation of, on, or by means of water” (Hofmeyr, 2019, in Bethlehem, 2022, p. 343). Rogers’ excellent (2022) work on “nautico-imperialism” attends to many of the political underpinnings that situated Britain as a “maritime empire.” However, although there is a broad and deep proliferation of studies acknowledging the maritime and oceanic attributes of settler-colonialism across the British empire, “tying hydrocolonial analyses too rigidly to oceanic studies risks prematurely ceding important arenas of intervention” (Bethlehem, 2022, p. 343). As such, a turn to waterscapes such as rivers, swamps, and creeks engages a more acute spatial analyses of settler-colonial water histories.

Furthermore, the colonial-water theme emerges again in work by Morgan (2015, p. 11), who brings forth the notion of a historicised “hydro-resilience” to describe “the historical product of an interaction of ecological, geographical, cultural, socioeconomic, and political factors, which together shape the extent to which they are adversely affected by a real or perceived lack of water.” By working to uncomplicate water’s presence in settler-colonial histories, these scholars are affirming, in many ways quite explicitly, the point that settler-colonialism is not an abstract event set in the past. Rather, it is an ongoing structural project (Glenn, 2015; Kēhaulani Kauanui, 2016; Wolfe, 2006). As such, essentialising settler-colonialism to a “structure” presents it as something that might be “un-structured” or dismantled; this, of course, is in reference to the call to decolonise settler-colonial states. However, in this article, I posit that another interpretation of the “structure” of settler-colonialism might warrant consideration; I move to affirm that many conceptions of settler-colonialism often struggle to attend to the material and the post-structuralist components which it also comprises. In essence, when it is said that settler-colonialism is a structure, not an event, I press the point that the “structure” is, quite tangibly, materialised in infrastructure. By doing so, I open up possibilities by which to consider dismantling and altogether transforming infrastructures as a material realisation of decolonial politics. What I am not suggesting is that material infrastructures can simply be pulled down and torn up and then replaced with another in isolation of discourse; politics of injustice must be addressed in the discursive as well as the material. Furthermore, as a tool for political change decolonisation is only half of the picture; Indigenising and Indigenisation should come forward in place of settler-colonial practices, policies, systems, and structures. These politics help us unpack the relational settings that brought about the marginalisation of First Nations peoples, knowledges, values, and beliefs in the first place.

2.1 Anti-colonial hydraulic urban co-design praxis

To affirm First Nations presence and ownership in the city, I reflect on how water infrastructures are never designed, planned, managed, regulated, or governed without the influence of politics. As a settler-descendent academic living and working in Sydney, the grounding of this work as fundamentally anti-colonial permeates into research methodology and frames my reflections of the data, which, by and large, are colonial.

In terms of design, questions about who is and who is not doing the designing are most significant (Coyne, 2023). But so, too, are questions about what kinds of knowledges are being used to inform the design process. What realities and beliefs are included and excluded? What futures are imagined? And who inhabits or uses these futures? One technique that is framed as acting to counter dominant design practice is Community Based Co-Design (CBCD). Seen by some, such as Al-Kodmany (2001), CBCD is often perceived to be the way to “bridge the gap between technical and local knowledge.” What underpins the idea of CBCD is a notion that “outside expertise” is, in some way, useful to “complete” the necessary steps to achieve a beneficial project that might be beyond the technical background of the community where the co-designing is taking place. However, existing unequal power relations can, and often do, exacerbate underlying systemic injustices and prejudices. Furthermore, unless co-design is followed through with radical reorientations of planning, management, regulation, and governance as well, then the intended restructuring of power relations is likely to emerge as thin, or actually perpetuate existing injustices and deepen traumas. In this sense, effective and “meaningful” CBCD should, in the settler-colonial setting, be guided by an anti-colonial politics.

Co-designing is perceived as an expression of public participation and a way forward to highlight and affirm First Nations knowledges in urban environments (Parsons et al., 2016). Sharifi et al. (2017) argue for the benefits of co-design, especially as a feature of developing urban resilience. As a tool, co-design can be understood through the NSW Council of Social Service’s definition as “the design of services and products that involve people who use or are affected by that service or product” (NCOSS, 2017). When framed around specific structured power/knowledge conditions, co-design might enable both capacity building and resilience. These conditions are centred around answers to questions posed by Sharifi et al. (2017): “Resilience for whom? Resilience of what? Resilience to what?” However, although capacity building and resilience might work in some way to address the concerns of injustice, these attributes perpetuate existing structural conditions that are imposing harm onto the community doing the resilience (MacKinnon & Derickson, 2013; Thomas et al., 2016). The idea that First Nations communities should be resilient to socio-environmental challenges obfuscates both the responsibility of those continuing the harm in the first place to stop and the ability of those harmed to adapt or mitigate (capacity-build) against damages that are beyond their control, among them structural racism, intergenerational trauma, land dispossession, and capitalist extractive environmental destruction.

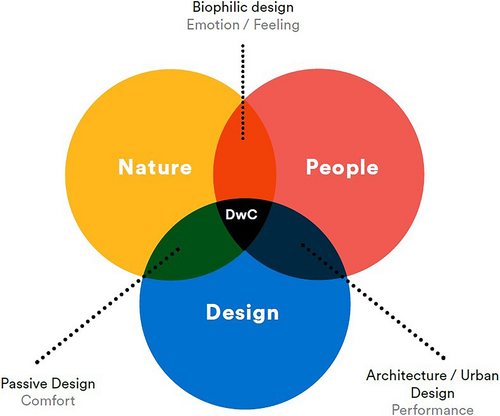

Through co-design, however, First Nations community members might potentially take ownership over settler-colonial infrastructures and transform urban spaces in a way that reflects First Nations onto epistemologies and ultimately un-settle urban waterscapes across Sydney. For example, leading the way in this space is work being done in Sydney by First Nations designers and architects such as Alison Page (Walbanga/Wadi Wadi), Dillon Kombummerri (Yugembeh/Goori), Kevin O’Brien (Kaurereg/Meriam Mir), Jefa Greenaway (Wailwan/Kamilaroi), Danièle Hromek (Budawang/Yuin), and Craig Kerslake (Wiradjuri) in agencies such as Yerrabingin, Djinjama, Nguluway Design Inc., and Bangawarra. A substantial portion of the latter part of the article is dedicated to discussing their praxis. Their names do not represent an exhaustive list, and every year, more First Nations practitioners enter this space. These people and agencies are doing remarkable work to highlight the deep interconnections between water and society, and they provide exceptional examples of culturally inclusive water urban design in action (Figure 1) (Coyne et al., 2020). Such work also shows the threading together of a political, relational ontology built and dependent on kinship with Country (Country et al., 2016; Foster et al., 2020; Lloyd et al., 2012). These ideas reappear later as I frame how future infrastructures are being designed in ways that address the above sentiment. The next section considers what infrastructures are and examines how they are perceived.

2.2 Challenging dead infrastructure

Emerging from considerations of a relational hydrosocial approach (Boelens et al., 2016; Linton & Budds, 2014; Swyngedouw, 2009), a hydro-onto-epistemological enquiry that engages with diverse ethnogeomorphological settings (Wilcock et al., 2013) across urban spaces opens up possibilities for highly nuanced, detailed, and Country-based design praxis. In using the term ethnogeomorphological, I am seeking to highlight, as Wilcock et al. (2013) do, that there is scope, and indeed cause to “move beyond cross-disciplinary scientific disciplines (and their associated epistemologies) towards a shared (if contested) platform of knowledge transfer and communication that reflects multiple ways of connecting to landscapes.”

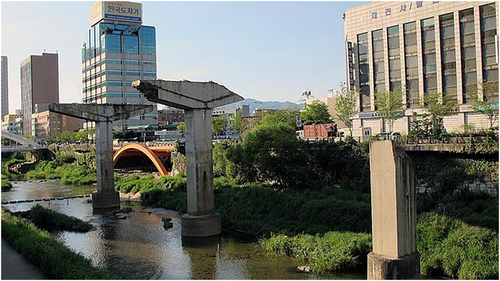

In shaping landscapes, water is central to many geomorphological processes—for example, the shaping of rivers through erosion, permeating into the earth to form vast, volumetric groundwater systems, or the propensity and proliferation of wetlands, estuaries, and other watery features. Acknowledging that both the creation and understanding of these processes are mediated through social, cultural, and political factors, an ethnogeomorphological approach highlights the many ways in which waters and society come together. By showing this connection, the role of certain kinds of stormwater infrastructures can begin to carry with it not just practical applications to reduce flooding or mitigate pollution, for example, but actually be representative of local customs, knowledges, beliefs, and values; the hydrosocial understanding of the processes, which many contemporary stormwater infrastructure projects make use of, is key to considering and co-designing culturally inclusive urban water infrastructures (Coyne et al., 2020). Both ecologically and socially, then, infrastructures can—and should—be thought of not as dead, neutral, and mundane, but rather as alive, charged, and dynamic. This vibrancy of infrastructures is especially the case when the relationality of these infrastructures is set against human/more-than-human responsibilities, duties, and systems. Such relationality between infrastructure, society, and the more-than-human can be understood in the concept of kinfrastructure (Coyne, 2023). Kinfrastructure actively defies conventional imaginaries of nonliving infrastructures and seeks to affirm the connections that infrastructures of all kinds might have with humans of all kinds. In particular, human-created infrastructures shape and are shaped by the more-than-human cohabitations, exchanges, and dependencies. The images, for example, below illustrate the complex entanglements that an infrastructure like a stormwater drain can present (Figure 2).

Furthermore, it is important to consider hydro-onoto-epistemology, a coalescence of work on hydro-epistemologies (Mukhopadhyay & Choudry, 2020; Staddon & Everard, 2017) and hydro-ontology (Brodaric & Hahmann, 2014; Hahmann & Brodaric, 2012) and informed by Povinelli’s (2016) geontologies. This epistemology advocates for a responsive consideration of the way waters are imagined, known, and manifested in design, planning, management, and governance. Acknowledging Povinelli’s work and her concept of “geontopower,” which describes “the regulation of Life and Nonlife,” I advocate for a “hydrontopower” to advance recognition that water’s existence is always mediated through cultural contextualisation and politically informed regulations. This notion firmly situates ontology alongside epistemology so that “attention is [oriented to thinking about] how humans comprise bundles of social, material, and discursive relations and are constantly in flux and in a state of becoming” (Henderson & Dombrowski 2017, p. 307, original emphasis). The ways in which waters are set within these relations are therefore analysed as being a condition of specific ways water is both understood and lived. Acknowledging the diverse ways in which waters are unevenly experienced by different groups of people in uneven ways is well established in the substantial literature that exists in political ecology (Bakker, 2003; Boelens, 2015; Millington, 2018, 2021; Sultana, 2018; Swyngedouw, 1996, 2009; Swyngedouw et al., 2002; Swyngedouw & Heynen, 2003). That work emerges to be especially pertinent to my argument given the ways various hydro-onto-epistemologies are unevenly situated in contemporary water governance, management, and design.

Broadly speaking, water politics has several themes. In Sydney, these themes include issues of water scarcity, flooding, sewage management, water recycling, groundwater management, irrigation, river and wetland management, and pollution. These themes do not begin to account for the interconnected issues of more widespread ecological management and governance decisions by national, state, local, and private/commercial actors. I look at stormwater and both “grey” infrastructure and “blue-green” infrastructure (BGI). The former refers to, typically, concrete, or metal stormwater assets such as drains, canals, or pipes; the latter is a more innovative reinterpretation of stormwater infrastructure manifest as, normally, water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) features such as swales, bio-retention ponds, permeable surfaces, and artificially constructed wetlands and rain gardens. Known as sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS), low impact development (LID), or sponge cities, the movement to include BGI into new or retrofitted urban design projects is often framed as a benign, apolitical subset of local council drainage committees. I aim to show that decisions about whether to include BGI or not are inherently linked to specific political agendas, namely, neoliberal gentrification projects (Blok, 2020; Safransky, 2014; Shi, 2020). But also, BGI is a hallmark feature of many progressive municipalities around the world (Bedla & Halecki, 2021; Cousins & Hill, 2021; O’Donnell et al., 2021). Because of the BGI’s role in mediating and responding to climate change-related challenges such as longer dry periods or more intense wet periods, BGI is used as a tool to showcase proactive governance. That said, for many cities and municipalities the design, construction, and maintenance of BGI are often out of step with either their politics or their capabilities. Typically, it is cheaper, quicker, and less of a hassle to make use of conventional grey infrastructure to manage stormwater. Pipes, drains, and canals are, broadly speaking, predictable and familiar to urban stormwater managers. In a world driven by risk society thinking (Beck, 1992), BGIs inherit dynamism is a concern.

2.3 Unpacking Designing with Country

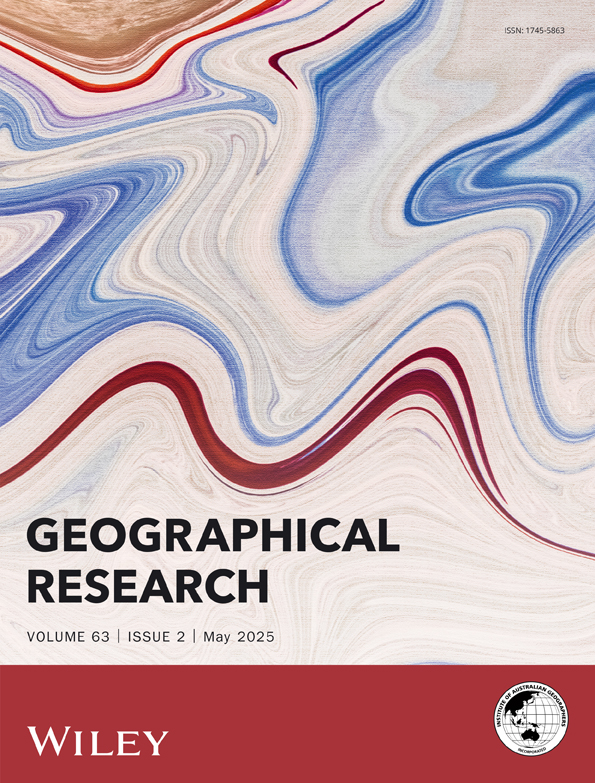

Taking the concept of BGI and acknowledging the interconnections that these infrastructures have, in 2017 Tyrell Studio, the New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment, and the Office of the General Architect of NSW (GANSW) produced the “Sydney Green Grid” (Tyrell Studio, 2017). The “grid” itself is a composition of four main landscape uses: the agricultural grid, the recreational grid, the ecological grid, and the hydrological grid. Other more “public grids” include the transport grid, the utilities grid, the development grid, and the historical grid. Pressingly, within this original composition, there is an apparent absence of a First Nations Grid, Indigenous Grid, or Aboriginal Grid.

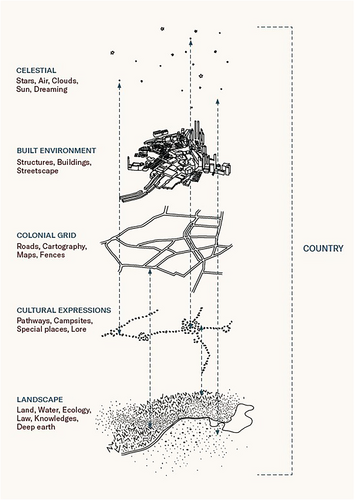

To address this absence, Principal Architect for the GANSW Dillon Kombumerri (Yugembir/Goori) as well as First Nations Spatial Designer Danièle Hromek (Budawang/Yuin) advocates for “Beginning with Country” through the “Ochre Grid” (2020) (Figure 3). Within the illustration, each grid represents a layer of what urban planners might consider when designing a new development. The top five grids (public, agricultural, recreational, ecological, and hydrological) have been present in the planning and design of cities for most of the last century. However, the “ochre grid” sees both planning and design begin with Country. Working with the ochre grid as a foundational reference point is a notion referred to by the Office of the GANSW and articulated by Kombumerri and Hromek as Designing with Country—what might be thought of as an Australian-specific form of First Nations urban design. This concept emerged and was solidified during the 2018 Designing with Country Forum held in Sydney. The working paper that followed clarifies and opens up many themes from the forum. From it, Hromek (2020, p. 2) states that there “is a clear need for tools and strategies to assist both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities to share knowledge about Aboriginal places as well as places of shared cultural and heritage significance—and to understand how we can all work to respect and protect sensitive sites and to strengthen culture.” At the centre of Hromek’s words are a push towards the development of a new way of designing urban places that are considered culturally and ecologically resilient and just.

3 OF CREEKS AND SWAMPS

The Sydney region is woven with a huge number of waterscapes threaded above and below ground. In the story of Sydney, an abundance of cases reflect the complexities of rapid-pace settler-colonialism’s impact on people and place. Here, the Tank Stream is used to showcase the politics and culture of the city and acknowledge the incredible transformation of the space from vibrant ecology to sanitised infrastructure. Importantly, I want to affirm that the Tank Stream—as “infrastructure”—emerged from a very particular politic; the stream as it is now emblematic of a network of settler-colonial infrastructures that silenced First Nations knowledges and experiences and proclaimed British ideals of hydro-imperialism.

In seeking to map this relational experience, the case shows a history of First Nations dispossession, the creation of settler-colonial infrastructures, and a complex setting where the futures of these infrastructures remain up for debate. Before the case is examined, an overview of the broader hydrosocial setting of Sydney is required.

3.1 Sydney—harbour city, river city, swamp city … water city

Although the breadth of British settler-colonialism across the region, the state, and the continent is significant, the specific infrastructures considered here are situated in the eastern, urban parts of the Sydney peninsula.

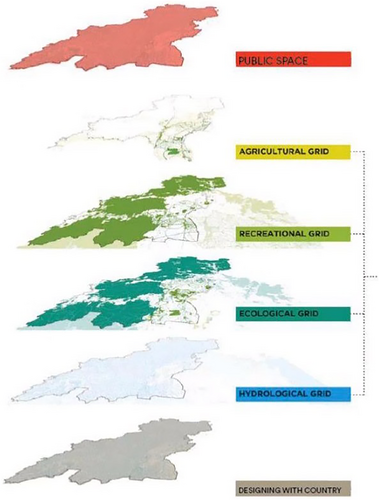

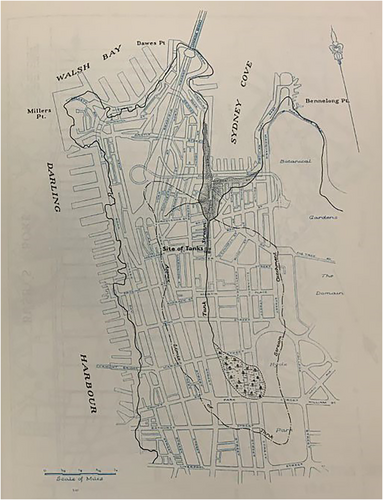

Sydney, or what is now known as the city of Sydney, is probably most recognised by Sydney Harbour. As a waterway, it defines much of contemporary Sydney. As its tendrils spread into the many coves, bays, and estuaries across the harbour, it sends a watery pulse into the daily lives and cultural identities of those who live near to it or travel through, over, and under it. Central to the way the harbour interacts with the rest of the city is that this waterbody captures much of the abundant rain that falls across the city. Indeed, as Figure 4 illustrates, the encompassing breadth of this catchment showcases the significance that watershed thinking is to managing urban waterways. This distinct hydrological feature is quite significant here.

Throughout its colonial histories, Sydney’s soggy geographies—be they swamps or wetlands, marshes, bogs, mud flats, or even creeks—were connected, quite firmly, to the idea of undesirability. For instance, mapping a history of inner-Sydney’s swampy places also often presents a history of Sydney’s slum geographies. Blackwattle Creek, for example, flowed across what is now Broadway and into Blackwattle Swamp near Pyrmont was the site of intense slum development in the late 19th century (Sneddon, 2006). That waterscapes were associated with slums is also largely connected to the kinds of industries that took place there; in this case, noxious trades such as slaughterhouses made use of the intermittently flowing water.

Firmly connected to the idea of disease and danger, the creeks and swamps did not receive the same care and attention from the British that they did from the many First Nations peoples who were already living—thriving—in these spaces. In the Tank Stream Valley, these are the Gadigal/Cadigal peoples, as well as the many groups who moved through and shared lands and waters with these groups. For example, the springs, creeks, and swamps around Rose Bay and Rushcutters Bay on the southern rim of the harbour have been significant First Nations settlement sites in eastern Sydney for many reasons including being locales of abundant food and building material (Irish, 2017).

Several runs of fresh water were found in different parts of the bay, but there did not appear to be any situation to which there was not some very strong objection. In the northern part of it [Botany Bay] is a small creek, which runs a considerable way into the country, but it has water only for a boat, the sides of it are frequently overflowed, and the low lands near it are a perfect swamp. The western branch of the bay is continued to a great extent, but the officers sent to examine it could not find there any supply of fresh water, except in very small drains.—18 January 1788

Between Sydney Cove and Botany Bay the first space is occupied by a wood, in some parts a mile and a half, in others three miles across; beyond that, is a kind of heath, poor, sandy, and full of swamps.—February 1788 (emphasis added)

In three days, with great difficulty, they passed the swamps and marshes which lie near the harbour. Nothing can more fully point out the great improvement which may be made by the industry of a civilized people in this country, than the circumstances of the small streams which descend into Port Jackson. They all proceed from swamps produced by the stagnation of the water after rising from the springs. When the obstacles which impede their course can be removed, and free channels opened through which they may flow, the adjacent ground will gradually be drained, and the streams themselves will become more useful; at the same time habitable and salubrious situations will be gained in places where at present perpetual damps prevail, and the air itself appears to stagnate.—15 April 1788 (emphasis added)

Within the text above, the absolute resolution with which water infrastructure in the city was imagined is inextricably linked to connotations of “progress.” The goal was to rid Sydney of “places where at present perpetual damps prevail.” To such ends, a massive transformation of Sydney’s waterscapes was to take place; it was a transformation that would leave the region almost totally unrecognisable.

3.2 The tank stream

Across the Sydney city, the topography varies greatly. Entering Sydney Harbour from the sea, towering golden sandstone cliffs—north and south head—rise up like sentinels protecting the calm water of the harbour. Bordering the harbour, undulating headlands jut out. Two particular headlands of the southern edge—coodyee (Millers Point) and tubowgule (Bennelong Point)—spread their rocky arms out to protect war’ran/warane/warang (Sydney Cove/Circular Quay). Looking south from the cove’s foreshore, the immense Sydney CBD now rises up. Indeed, it really does rise—to 90 metres above sea level at Park Street near Hyde Park. In many ways, it is this topographical variation that dictates the flow of water across the city. In the depression between the coodyee and tubowgule headlands, a lush stream once flowed through a forested valley. The headlands emerged from ridgelines that reach back to create the valley shape. Figure 5 shows the path of the Tank Stream as it looked at the time of British arrival, superimposed onto a late 20th-century map of the CBD. The stream flowed northwards from a swampy wetland higher up in what is now Hyde Park. The swamp here emerged from a combination of deep underground springs and Sydney’s ever-variable rainfall. This stream has no recorded First Nations name. However, when Arthur Phillip landed in this place, it was known as the Gadigal/Cadigal Stream (Karskens, 2009). This name—Gadigal/Cadigal—is the name that is given to the First Nations people of this region (Karskens, 2009). For the Gadigal people, this stream, the associated Hyde Park swamp, and the wide mudflats at Sydney Cove all provided an abundance of food—fish, crustacean, oysters, fruits, seeds and tubers, and feeding wallabies and kangaroos—as well as materials for tools and, of course, abundant fresh drinking water. And it was this last resource that brought Phillip to this nourishing cove. Importantly, these relations between First Nations people, Settlers, and the more-than-human are relegated to the past but have continued to play out in complex ways up into today. In the proceeding commentary, this entire waterscape—the swamp, the stream, and the mudflats—is captured in the term “Tank Stream Valley.”

Much has been written about the Tank Stream. Work by Cathcart (2009) has presented an evocative and detailed recount of the Stream’s role in shaping the city’s history. To avoid repeating a story much told across Sydney’s early colonial history, I will detail only an overview. In the early years of the Sydney settlement, fresh drinking water was, quite plainly, essential. Phillip chose Sydney Cove because of what he thought was a reliable source of fresh drinking water. However, as has been written extensively, the climatic conditions when the settlers arrived proved notably dynamic (Gergis et al., 2010). A period of extremely low rainfall meant that something had to be done to ensure stable provision of water (Gergis et al., 2009). And so, perhaps as per the technology learnt from British time in India (Goodall, 2008), three large tanks were carved out from the sandstone bedrock adjacent to the stream. However, as much as the tanks ensured nourishment for the settlement, it also became the site of concentrated sedimentation and pollution (Karskens, 2009; McLoughlin, 2000); coupled with extensive dredging of Sydney Cove, largely brought about by the aforementioned sedimentation and pollution, by 1825, the stream became unusable as a source of drinking water. By the 1860s, it was progressively covered over and used exclusively as drainage.

Although the story of the Tank Stream showcases the unsuccessful attempts at environmental management by the British, the infrastructure that was created out of the steam’s use remains. Today, although the tanks themselves are no longer present, the Tank Stream still flows, except it now is entirely undergrounded and functions to take the city’s stormwater off the streets and into the harbour. The drainage infrastructure lies deep under the fabric of the city, and yet the memory of the stream permeates up from below. Features such as Tank Stream Way, the Tank Stream Hotel, and a smattering of plaques and public artworks across the CBD now hint at what is below. Furthermore, although often framed as a “ghost stream” (Gies, 2022), undergrounded waterscapes like the Tank Stream can—and I argue—should be understood as still being kinfrastructure too. Indeed, in a nearby drain, eels have been spotted moving with the waters in defiance of macro and micro pollutants (Figure 6).

The surface-level references to the stream below present an attempt at acknowledging the valley’s history, and the presence of more-than-human inhabitants in subterranean water infrastructures highlights the aliveness of these spaces, but what might a future Tank Stream look like? As climate change and increasing impermeable urban development take place, the kinds of cities that emerge will need to look to alternative design paradigms, alternative planning agendas, alternative management techniques, and, fundamentally, alternative governance structures.

One example of these “alternatives” is that of “daylighting” undergrounded rivers and streams (Delibas & Tezer, 2017; McEwen et al., 2020; Wild et al., 2011). Daylighting, also known as deculverting, is a process whereby rivers, creeks, or streams that were once open to the surface and then subsequently covered over or undergrounded by urban development are then “reopened” back up to the daylight. Around the world, many cities are going through this process. In Seoul, South Korea, the Cheonggyecheon Creek was daylighted (Figure 7) and integrated back into the urban fabric so as to bring an awareness of the presence of water in the city.

Daylighting showcases, in a very tangible way, what a reimaging or restructuring of ingrained settler-colonial urban design can look like. Additional advantages to bringing an urban stream, creek, or river back to the surface include a variety of ecological benefits, a reduction in flood risks, community recreation (Wild et al., 2011), and the potential to reflect local cultural knowledges and relational political ontologies. It is with this last point that the opportunity for affirming an anti-colonial urban design process might emerge from. Daylighting the stream provides scope for buried geographies, buried stories, and buried knowledges to be a part of Sydney’s inner-city streetscape.

3.3 “Wasted” geographies

The infrastructure of the Tank Stream drain—as opposed to creek—still largely functions in line with previous imaginaries of these lands and waters as “wasteland.” That the Hyde Park Swamp, Tank Stream, and Sydney Cove mudflats were seen as “waste” fits into the idea that, as Libby Porter notes, “waste was also intrinsically related to the future: it had potential for improvement, cultivation and civilisation, a moral right and duty that colonisers took very seriously.” Porter (2018, p. 62) continues, “this was contrasted with what Aboriginal people appeared to do with land.” The water that moved across the valley, slowly, nourishing and fundamentally being Country, was, evidently, at odds with the colonial idea of what water, in particular stormwater, could be and, foundationally, what waterscapes such as these could do.

Infrastructures such as the Tank Stream shaped the way settler-colonial hydraulic urban design has materialised in Sydney. Importantly, what I note as one of the most significant materialisations was that of sending water underground. From the covering of the Tank Stream to the carving of Busby’s Bore in Lachlan Swamps, or the storing of water in vast underground reservoirs such as in Paddington and Surry Hills, or through to the network of underground pipes and drains that weave underneath contemporary Sydney, the undergrounding of water infrastructure obfuscates, by and large, human interactions with waters. Seeing the quick removal of water from the urban environment as efficient emerges from a way of thinking about water that lingers on from colonial notions of hydrology. Seeing human domination over water as foundational to civilisational progress, I concur with Sara Pritchard’s term of “hydro-imperial” and see the transformation of the Tank Stream Valley’s waterscapes into gutters and drains as a key component of the British hydro-imperial project in Sydney. In separating water from society—by sending in underground—there is a separation of water-related knowledge practice (how to know water) and the memory of water.

Since British occupation, there have been numerous floods across Sydney. The low-lying areas around inner-south and inner-west Sydney have all experienced intense flooding over recorded European presence in the city. And it is not just confined to the past. Numerous contemporary instances of urban flooding abound. In March 2021, heavy rains saw Centennial Park’s stormwater infrastructure struggle to respond to the deluge. Across the Park, sandstone-lined ponds overfilled their banks and playing fields were turned into vast shallow quagmires, pond edges overflowed, and swamps and marshes re-emerged to inundate paperbark forests and reed-filled ponds (Figure 8).

Although this and other subsequent flood events across the region might rightly be connected to the progressive intensification of climate change-related rain fluctuations, others are beginning to acknowledge that perhaps the abundance of homogeneously designed “grey infrastructures,” such as drains, pipes, or canals, might be exacerbating the issue. Journalist Erica Geis’ 2022 novel Water Always Wins responds to this point in depth. Advocating for “Slow Water,” Geis presents a raft of alternative water relations from across the world that have, as their overarching sentiment, the knowledge that water should be treated as an ally rather than enemy. Having read and been highly influenced by Sue Castrique’s 2019 Essay “On the Margins of the Good Swamp,” I want to move to close up by reflecting, as she does, on Water’s memory, and how, as she puts it, “water remembers the way.”

In thinking of such matters, I also contemplate on the Tank Stream Valley and the memory that is embedded within its waters, but also, significantly, within those who have the longest memory of these waters, the traditional First Nations custodians of the valley. I move now to a reflection. A reflection on the future of the waterscapes … the future of the drains, canals, fountains, and ponds across Sydney—how might these spaces be reworked away from their settler-coloniality?

3.4 Blue-green-ochre infrastructure

Echoing Geis’ work, I note the growing trend across cities to “renaturalise” their waterways, from concrete canals to creeks lined with stone and grasses. The progression towards renaturalisation reflects a recognition among urban designers, engineers, and landscape architects that “blue-green” infrastructure has the potential to address the “betterment” of urban stormwater features. Renaturalisation is also, often, embedded against other “alternative” design paradigms. Most pertinent here is the notion of Designing with Country.

Country soars high into the atmosphere, deep into the planet crust and far into the oceans. Country incorporates both the tangible and the intangible, for instance, all the knowledges and cultural practices associated with land. People are part of Country, and their/our identity is derived in a large way in relation to Country. Their/our belonging, nurturing and reciprocal relationships come through our connection to Country. In this way Country is key to our health and wellbeing.

So, caring for Country is not only caring for land; it is also caring for themselves/ourselves (Hromek, 2018). Country holds everything, including spaces and places. Spaces and places, even those in urban centres, are thus full of Country (Hromek, 2018) and therefore need appropriate cultural care to ensure healthy landscapes.

As mentioned in the text above, the underpinnings of Country help to shape the material realities of everyday lived experiences for First Nations peoples. So central is the notion of Country that it is the keystone attribute of many design principles, namely, Designing with Country. The 2021 book “Design: building on Country” by Alison Page and Paul Memmott delves into much of the theoretical and practical aspects of this design practice. Within the book, Page pens a reflection on the application of the International Indigenous Design Charter (IIDC). The charter aims “to promote understanding among the practitioners, clients and the buyers of design including governments, corporations, businesses and not-for-profit organisations.” As Page acknowledges in their writing, the diverse philosophies and expressions of “Indigenous Design” across international settings might share “common ground” but are dependent on being “driven by Indigenous people at all levels” (Page & Memmott, 2021, p. 169).

The IIDC itself outlines a set of 10 best practice protocols: (1) Indigenous led; (2) self-determined; (3) community specific; (4) deep listening; (5) Indigenous knowledge; (6) shared knowledge (collaboration, co-creation, procurement); (7) shared benefits; (8) impact of design; (9) legal and moral; and (10) charter implementation (Kennedy et al., 2018, p. 8). These protocols can be—and are—applied to instances of a range of design settings including architecture, graphic design, fashion and textiles, media, and technology (including, among others, gaming, graphic novels, and VR/AR), a variety of user experience outputs, and—significantly for this article—landscape architecture and urban design.

I move to open up the discussion surrounding these infrastructures and their understanding as Country. I ask, while the aesthetics of renaturalised places as blue-green is ticking a lot of the right boxes, what of the ochre grid? What of truly, meaningfully, Designing with Country … healing Country?

In being attentive to the various “grids,” these “new” infrastructures are, I think, a step in the right direction. However, I take heed from and follow in the work of Hromeck and Kombumerri. I wonder, is it perhaps also time for “ochre infrastructure” too? Seeing the Tank Stream as blue-green-ochre infrastructure has, I suggest, huge potential for making real change.

4 SPECULATIVE RESTRUCTURING OF SETTLER-COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES

Although many designers and agencies are moving in an appropriate direction, if non-First Nations designers continue not to acknowledge a place’s historic and living First Nations heritage and not to engage in meaningful co-design processes, they are missing an opportunity—an obligation even—to right wrongs and to re-Indigenise the city. Here, I here allude to the governance of these infrastructures; even if “cultural landscapes” become more present across the city, I wonder how would the governance—the responsibilities and risks, the maintenance and ownership—of these blue-green-ochre infrastructures look like moving forward?

The work needed to materialise any such infrastructural shift is, quite simply, monumental. As Hromek (2021, p. 32) acknowledges, “the landscape has been smoothed off by colonial processes that flattened surfaces, removed landmarks and put concrete, asphalt and glass on top that weigh it down.” The processes of re-texturing these landscapes can be done in many ways. Typically, as is the case in most urban retrofitting projects, it would take the form of a kind of “sensitive” design process. Here, “sensitive” is an encompassing term to refer to all that is sustainable, eco, or bio. Another design praxis might seek to simply address a “pressing” infrastructural discrepancy by moving to implement an “affordable” and “efficient” project—cheap and quick. However, although the flaws of the latter design process are (hopefully) obvious, I and others see the former design process as good, but not good enough. “Sensitive” design that seeks to take from nature, from place, from Country, and not work with and for nature, place, and Country is only ever going to continue the damaging practices of settler-colonialism; it certainly will not come close to achieving anti-colonial outcomes.

Work mentioned earlier on crafting WSUD and other “sensitive” and “sustainable” design such as daylighting might address much of the immediate, obvious ecological and social needs of retrofitted urban design. However, for places such as the Tank Stream to be daylighted would require vast changes to the urban fabric of the Sydney CBD. These changes can happen, and the benefits of daylighting the Tank Stream abound. For a waterscape such as the Tank Stream to come to the surface once more, removing the tarmac and the concrete will only be one part of the process. Fundamentally, this work would require reimagining Sydney beyond the settler-colonial infrastructures that have been imposed onto it. Although work to daylight the Tank Stream is still far off, other projects are taking place across the city. Projects present tangible indications that settler-colonial infrastructures are being reimagined.

4.1 Doing First Nations urban design

In Sydney, two First Nations-owned design agencies are crafting a path forward in this space: Yerrabingin and Djinjama. Yerrabingin, meaning “we walk together” in the Mooktung language, began in 2018 and works to “[Support] a socially inclusive, resilient, and innovative community based on, honouring the wisdom and kinship of all cultures, captured through the lens of custodianship” (Yerrabingin, 2020). Central to Yerrabingin’s design ethos is a promotion of marginalised voices, coupled with an aim to “destabilise mainstream project processes and outcomes” (Mouritz & Breedon, 2022, p. 99). Their work has been hugely successful in recent years and their presence in the city is actively materialising the ochre-grid. Djinjama, meaning “to make, complete or build something” in the Dhurga language, was established in 2020. In their own words, “Djinjama brings Country into the centre of the design process in order to substantially affect Indigenous rights and elevate culture in the built environment and bring health to Country” (Djinjama, 2021). Working in strides to create collaborative and generative design, Djinjama has carved itself as respectful and caring, in the face of an industry built on dispossession and greed.

Underpinning the design praxis of both Yerrabingin and Djinjama is the concept of CBCD. The movement towards an anti-colonial and First Nations co-design paradigm must be based off a reimagining of what infrastructure is and can do. It must also situate a firm connection to reflecting on Country. If Country is considered as an active agent (Wright et al., 2012), then co-design must also work with Country, as well as the communities who live on and with Country—acknowledging, very firmly, that Country is not an “out-there” but is also the urban (Porter, 2018; Potter, 2012). Produced by Hromek (2020), Figure 9 shows the true connectivity and permeability with which Country is expressed in the built environment. In this figure, Country transcends liminal boundaries and volumetric constraints and so design with Country must similarly work across these expansive perspectives.

In Sydney, un-settling means working towards dismantling the dominant paradigms of knowledge that underpin contemporary urban design and landscape architecture. It is this avenue where I bring in discourses surrounding the key theories of First Nations design. First Nations urban design is the active concept that underpins a way of un-settling the development of cities, by being constantly attentive to the fact that cities in settler-colonial states have been constructed on First Nations lands and waters.

- Architecture considers design and people (informed by nature). Architecture without people is just a sculptural object.

- Passive design considers design and nature, and when used by people becomes environmental design.

- Biophilic design considers the innate relationship between people and nature. Informed by design, this relationship could be understood as a genesis for Indigenous architecture.

The breadth of practical applications for designing with Country is its strength. That designing with Country could, for instance, be applied to the redevelopment of a streetscape, a medical centre or a parkland, makes it a resilient and adaptable tool for First Nations communities to draw upon. In the case of the urban waterscapes of Sydney—in particular, the network of stormwater infrastructure—the notion of setting the ochre grid as the primary layer for which to build on top of is fundamental. What designing with Country can offer is a bridge between bringing and affirming First Nations knowledges, together with making tangible changes for un-settling Sydney’s stormwater infrastructures. I look to the concepts laid out in the work of Kombumerri for how I might move beyond simply critiquing existing urban design and instead consider how the application of recognising injustices in settings across the city might contribute to the advancement of the field of First Nations urban design.

overtones of both displacing from settlements that occupy space and make places of privilege and exclusion, as well as troubling the everyday discourses of erasure of the histories of settlement as invasion, occupation, dispossession and violence.

At the heart of the process of un-settling is to carefully consider the spatial, social, political, and historical contexts that have enabled the settler-colony to benefit in the first place; this requires action. But first, I suggest, there is design.

5 CONCLUSION

I have presented the argument that to understand how water infrastructures associated with the settler-colonial project have been politicised, a nuanced interpretation of both water and history is required. I have also argued that an anti-colonial framing of how water infrastructures are designed and managed needs to happen. By introducing a push to reimagine what infrastructures might be and might do I urge designers, communities, and decision-makers to think sensitively and carefully and be driven by principles of inclusivity. Using the example of the Tank Stream, I suggest that dismantling settler-colonial infrastructures can only really address issues of injustice when First Nations design is given priority. It is my hope that the work presented is both a call-to-arms and acts as a guide to push the way water infrastructures are designed, planned, managed, regulated, and governed into being more culturally inclusive and just.

Central to my argument for an anti-colonial hydraulic urban co-design paradigm shift is a recognition of how power is embedded within design. With water-specific design projects, this recognition emerges with the concept of hydrontopower; this is an idea that affirms the unevenness with which certain knowledges and experiences around watery themes are considered. Acknowledging and integrating marginalised groups’ hydrontopowers can have far-reaching implications. Beyond including culturally relevant plants and including local art projects, inserting a hydrontopower framing into new urban design and landscape architecture projects shifts the focus to expand beyond the material and introduce questions of governance and sovereignty.

This shift also acknowledges and responds to ideas of kinship. I assert that understanding the duties, responsibilities, and obligations of people to care for constructed blue-green infrastructures can be framed as “kinfrastructure.” This concept emerges from considering not just what infrastructures might be, to what infrastructures might do—and what we as designers and creators might do for them.

Sydney presents a raft of potential other examples and case studies that might be sites of the kind of change I have discussed. Although there is momentum, the structural conditions of planning instruments, development agendas, and protocols are hindering progress. At the heart of this issue lie matters of First Nations sovereignty and a recognition that settler-colonialism is not a historical event, but an ongoing structure. Without acknowledging that infrastructures are politicised, change will not happen. Without addressing First Nations justice, then no amount of WSUD or daylighting will matter. It will only ever be another pipedream.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

No empirical data were collected for this work. The research is part of UNSW Doctoral Research, Ethics HC200986.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.