Emergent time-spaces of working from home: Lessons from pandemic geographies

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and consequent health regulations compelled office-based knowledge workers to work from home (WFH) en masse. Government and employer directives to WFH disrupted common norms of commuting to city office spaces and reshaped the geographies of office-based knowledge work, with potentially lasting implications. Pandemic-induced cohabitation of work-space and home-space saw more workers navigating the performance of paid labour in the home to produce new relational geographies of home, work, and worker. This paper provides a window on the lived experiences of the sizeable cohort of office-based knowledge workers displaced from Sydney’s CBD to undertake WFH in the Illawarra region during the pandemic. We explore the unfolding pandemic geographies of work and home by drawing together feminist economic geography and geographies of home literatures. Our analysis reveals the emergent and variegated time-spaces of WFH that emerged as the rhythms and routines of WFH shaped the home and vice versa. The analysis also reveals the differentiated agency of embodied workers to orchestrate emergent configurations of WFH, shaped by gender and by the socio-materialities of home shaped by size, tenure, and life-cycle stage. We conclude by drawing out important lines of analysis for further research as “hybrid work” evidently becomes entrenched post-COVID.

Key insights

New relational geographies of home, work, and worker were shaped through Covid-related work-from-home (WFH). Drawing on the voices of office workers compelled by lockdown orders to WFH, this Illawarra-based study reveals its varied configurations, which emerged as the rhythms and routines of WFH re-shaped the home, and vice versa. The study also reveals the differentiated agency of embodied workers to orchestrate these WFH configurations, shaped especially by gender and by the socio-materialities of home. WFH relied on unpaid work, with gendered labour both reinforced by the continuation of gendered labour paradigms and power geometries and, on occasion, subtly realigned.

1 INTRODUCTION

The social and economic disruptions precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic transformed socio-spatial relations in myriad ways. In labour markets where tasks could be undertaken remotely, disease control measures required employees to work from home (WFH). Office-based knowledge workers, in particular, were displaced from concentrations of central business district (CBD) workplaces. On top of social reproduction, home became the primary site of productivity and business connections (Craig & Churchill, 2021; Green et al., 2020; Jenkins & Smith, 2021). For their part, workers remade geographies of the home to accommodate the intensified demands of paid labour, crafting new time-spaces of WFH. Emergent post-pandemic labour geographies, characterised by a “new normal” of increased hybridity in the time-spaces of paid work, bring the likelihood that the materialities and meanings of work and home will transform in lasting ways. Such transformations include the (re)organisation of different work activities within the rhythms of everyday life as well as broader political-economic considerations, such as the effects on business performance, industrial relations (IR) laws, skill development, and opportunities for upward mobility (Cockayne, 2021; Warren & Gibson, 2023).

In light of this emergent “new normal,” a significant cross-disciplinary literature has appeared seeking to understand the implications and outcomes of WFH for workers, organisations and institutions of the state. Data from surveys and online questionnaires have been used by researchers to highlight the varied outcomes of COVID-induced WFH. For workers, the intensity and frequency of WFH, coupled with social differences related to class, gender, age, race, and citizenship status are seen to determine whether people have a positive or negative experience (Awada et al., 2021; Bolisani et al., 2020; Green et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2021; Oakman et al., 2022; Sutarto et al., 2022). However, under-represented in current research are fine-grained, qualitative approaches that provide deeper insights on worker’s lived experiences of WFH (cf. Rudrum et al., 2022). Such analyses are crucial for understanding how the home, diverse forms of work, household relationships, and community spaces matter to the experiences of WFH for differently positioned workers. They are equally important to unpacking the ways in which—in light of the intensification of WFH—the material aspects of home, such as physical size, tenure, social dynamics and connectivity, influence how, where and when workers do paid labour and, consequently, affect how paid work demands reconfigure material spaces and social relationships within the home. With such intimate, qualitative research into WFH currently under-developed, this paper contributes crucial insights on these emergent everyday geographies and the factors that shape them differentially.

Conceptually, we draw on feminist understandings of “life’s work” (Mitchell et al., 2004), rejecting dualistic separations of home/work and narrow representations of what constitutes work in favour of a relational approach cognisant of their multiple dimensions (Strauss, 2020; Werner et al., 2017). Our goal is to unpack the reconstituted times-spaces of labour in the home. Acknowledging that a range of social factors differentiates the agency of workers—the capacity to act effectively and achieve improved pay and/or conditions of work—our analysis shows how new intensities of paid labour emerge in the home. Such labour then intersects with a complex array of other (often gendered) work that constitutes everyday life within the materiality and sociality of the home space. Our research is focused on a study of workers displaced from Sydney’s CBD office spaces during the pandemic who were compelled by lockdown orders to WFH and thus had to negotiate the intensification of work within spaces of the home. We use qualitative methods and draw on the voices of workers to trace how they navigated this intensification personally, spatially, and temporally.1 Combining feminist scholarship and the geographies of home literature, we reveal the fine-grain of everyday experiences of WFH and show how intimate geographies of home, work, and worker unfolded through the pandemic. The paper thus contributes new empirical insights into the variegated time-spaces of WFH that emerged and shows how, amid the daily rhythms and routines of WFH, the home itself was reconfigured. Notably, we reveal workers’ varied capacities—differentiated agency (Warren, 2019)—to shape the conditions and time-spaces of WFH as they orchestrated and navigated the demands of paid/unpaid labour. Our findings, we argue, have significant ramifications for understanding how hybrid work unfolds and for its place-based impacts over the longer term.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we establish the theoretical underpinnings of the analysis before outlining the research methods in Section 3. Then our empirical analysis is presented in two substantive sections. First, in Section 4, we outline the varied configuration of WFH time-spaces using a series of vignettes. Then, in Section 5, we focus on the differentiated agency of workers to orchestrate WFH, emphasising gender and the socio-materialities of home as key vectors that differentially condition agency and shape emergent geographies of WFH and its experience by embodied workers. In Section 6, we conclude by reflecting on the importance of our findings as a guide for further research, crucial as hybrid work reconstitutes geographies of “home,” “work,” and “worker” and becomes embedded in future landscapes of work and employment.

2 RECONFIGURING THE TIME-SPACES OF WORK AND HOME IN THE PANDEMIC

Our investigation of the lived experiences of WFH among displaced office-based workers is informed by two bodies of scholarship: feminist economic geography (FEG) and the geographies of home. FEG offers a range of critical conceptual tools to grapple with the interconnectedness of socially-constructed categories such as paid/unpaid labour, production/producer, home/office, and mind/body while also providing a lens through which to consider differentiated power geometries and agency. Meanwhile, geographies of home scholarship provides a critical understanding of how home is relationally, materially and imaginatively shaped. By placing these literatures into dialogue, our analysis contributes rich insights into how home and work are (unevenly) co-constituted through the WFH process.

Feminist economic geographers have long advocated accounts that recognise the messy interdependence and intimate links between “work” across formal spaces of economic production and “everyday life” in home spaces of (gendered) social reproduction (Cameron & Gibson-Graham, 2003; Massey, 1995; McDowell, 2001).2 Much progress has been made in developing accounts that reject ideas of neatly bounded time-spaces of work/non-work, attuned to work’s dynamic, uneven, and untidy spatialities (Richardson, 2018). Although boundaries between “work” and “life” are blurry (Gray et al., 2017), the spatio-temporalities of home and work often differ in crucial ways (Massey, 1995; Werner et al., 2017). For example, within the capitalist space economy, home has long been porous to the demands of paid labour, yet the porosity usually flows one-way. Formal workplace rules, norms, and managerial expectations have demanded that matters of social life “outside” of work are “checked at the door” (Strauss, 2020; Warren, 2019).

During the pandemic, the large-scale, lockdown-induced relocation of paid work into home spaces overwhelmed attempts at the conventional separation of places of work and non-work. During extended lockdowns, life’s work—the “un- and under-paid work of maintaining everyday life outside the formal workplace” (Reid-Musson et al., 2020, p. 1461)—explicitly shared time-spaces with the constellation of activities that produce value-laden goods, throwing their interdependence into sharp relief. Workers not only had to shift how they performed paid labour but also had to create spaces for paid labour within the (already) messy realities of their homes. As the time-spaces of labour processes were reconfigured, home and work entered a more conspicuous union.

Feminist economic geography also conceptually and analytically attunes us to the changing time-spaces of WFH by sharpening our focus on working bodies—socially differentiated based on gender, race, class, sexuality, or citizenship—as critical elements of labour-power (Reid-Musson et al., 2020; Warren, 2016). This bodily awareness sensitises analysis to workers’ multiple identities and positionalities beyond those associated with employment and “doing” a specific job (Werner et al., 2017). In the contexts of WFH, feminist approaches encourage attention to lived experiences, household responsibilities, and social differences as they play out in time-space. Before the pandemic, WFH was depicted as enabling certain workers, particularly women, greater capacity to combine paid work with other activities, including care responsibilities (Reuschke, 2019). Yet emergent analyses of WFH in the pandemic suggest that the definition of women’s roles in the home around unpaid “life’s work” (Mitchell et al., 2004) may be reinforced (Aldossari & Chaudry, 2021; Chattopadhyay, 2021; International Labour Organization (ILO), 2021). Care responsibilities and other unpaid labour continued to fall disproportionately on women during lockdowns, underscored by “an intense emotional labour, as they tried to keep everyone calm and safe” (Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2020, p. 268).3 Through the pandemic, the home, it seems, continued to be positioned as a costless economic resource, with much of the reproductive labour that serves “productive labour” remaining unaccounted for (Jenkins & Smith, 2021), with repercussions, particularly for women’s agency in crafting positive WFH experiences.

Ultimately, FEG provides conceptual tools to analyse how bodies at work in the knowledge economy, long accustomed to office workspaces, adjusted to new working realities. These realities include the home accommodating more paid work alongside the “intense emotional labour” and diverse forms of (gendered) caring labour associated with social reproduction (McDowell, 2016). These insights are rendered more acute by turning to the geographies of home literature, which helps apprehend how the materialities and socio-spatial relations that constitute “home” shaped experiences of WFH during the pandemic and how, in turn, relationships of home were reshaped to support paid work. We argue that developing more nuanced interpretations of both dynamics is crucial to understanding the long-term ramifications of hybrid work and its implications for home, work, and worker.

2.1 Geographies of home

The relational approach adopted by many scholars examining geographies of home can productively gel with political economy frameworks often drawn on by feminist economic geographers (Werner et al., 2017). Conceptually, both frameworks recognise that home is co-produced out of diverse elements and draw attention to how uneven power relations are constituted (Easthope et al., 2020). Equally, feminist attention to the working body resonates with geographies of home that examine how embodied social beings comprise the materialities and imaginaries of home. Although the home’s material and imaginative dimensions have not been a strong focus for feminist economic geographers, these additional elements attend to what happens to home over time through the embodied subject (Nansen et al., 2011). As Blunt (2005, p. 506) explains, the “home is a material and an affective space, shaped by everyday practices, lived experiences, social relations, memories and emotions.” Home, then, is a space constructed at the intersection of concrete materialities and diachronic spatio-temporal imaginaries: as a complex relational space, home is associated with meanings of it that are mutable and change over time. The new intensities of paid labour in the home associated with lockdown-induced intensification of WFH triggered significant changes in people’s relationships to home, which are worthy of analytical attention.

Three dimensions of geographies of home scholarship offer productive entry points for this analysis. First is the conception of the home as encapsulating diverse socio-spatial relations (Blunt & Dowling, 2006). Home’s spatiality incorporates relations frequently sidelined or expected to be “checked at the door” of formal workplaces. The home is interwoven with human emotions, intimacy, familial relations, belonging, and domesticity (Hall, 2019). These personal, embodied qualities must be considered in efforts to understand the experiences of WFH. Equally, unlike corporate office spaces, home is not designed and curated around organisational principles that valorise and reinforce labour productivity (Boyle & McGuirk, 2012). Even as it is recognised that “the firm” is more than a “black box” driven purely by profit imperatives (Yeung, 2001), the home is more fully distinguished by socio-spatial relations not pre-defined by paid labour.

Second, recent scholarship has drawn attention to the multiple spatio-temporalities that constitute the home (Liu, 2021). Home is “a site where family members synchronise, come together and play out the complex performances that constitute everyday life … a space irrevocably enmeshed on a minute-by-minute basis with global events, wider society, and other places and times” (Nansen et al., 2009, p. 182). Externally imposed norms, values, and ideologies of time (for example, working hours) co-constitute the time-spaces of the home (Morgan, 2019). Ideas of home also involve an archive of memories and reflections from different spatial and temporal landscapes (Blunt & Sheringham, 2019). Understanding the pronounced shift of paid labour into the home through and beyond the pandemic requires engagement with intersecting temporal threads and the possibilities of change, contradiction, and ambivalence they entail (Blunt et al., 2020). A key concern related to the pandemic boom of WFH and its longer-termed ramifications, then, becomes how the complex socio-spatial relations of the home are negotiated when paid work becomes intensely focused there (see Liu, 2021). This negotiation needs to be understood in relation to the differentiated agency of embodied workers who are variously positioned in an employer organisation or wider labour market.

Third, bridging FEG and geographies of home and highlighting worker’s differentiated capacity to shape positive experiences of WFH, Massey (2005) provides coordinates for conceptualising the changing relationship between home, space and work. The pandemic-induced shift to WFH has created new expectations, management systems, and social dynamics that workers must navigate. For Massey (2005, p. 168), social relations are produced through the specificities of place and by relations that always extend beyond the immediate time-spaces in question. The socio-spatial relations of home encompass power geometries and questions of agency, which different household members negotiate (Carswell, 2016). Scholars have paid particular attention to gendered dimensions of the negotiation of diverse power geometries of home—concrete and imagined—noting how they enable dominant ideologies to be valorised whereas others are marginalised (Blunt & Dowling, 2006).

The relational conceptualisations and concomitant power geometries found in geographies of home scholarship combine effectively with insights drawn from FEG. Together this literature offers a productive orientation for analysing the time-spaces of WFH: this includes how work, home and worker were reconfigured through the pandemic, and where future lines of geographical research may focus as hybrid working becomes a more widespread and uneven experience within urban and regional economies.

3 CONTEXT AND METHODS

Traditionally, knowledge work has been linked to CBD office environments designed to incubate “information-rich” knowledge production (O’Neill & McGuirk, 2003). COVID-19 health orders required a redesign of the socio-spatial practices underpinning office-based knowledge work. For Sydney’s CBD and the Illawarra region—approximately 70 kilometres to the south (a 90-min commute by train)—this was consequential. Prior to COVID-19, office-based knowledge work dominated employment in Sydney’s CBD recognised as “Australia’s only global city and the leading knowledge-based economy in the nation” (CoS, 2020). Office-based industries constituted 85% of total employment in the City of Sydney.4 Of its 500,000-strong workforce, 23% worked in the financial sector, with another 20% employed in business and professional services.

On 23 March 2020, in light of COVID’s spread via workplaces and public transit, the New South Wales Premier announced: “If you have the capacity to work from home, you should do so.” Correspondingly, state health orders reshaped the geography of office-based knowledge work as CBD offices were abandoned and workers adapted to WFH. The Public Health Order was repealed eight months later, and by May 2021, office occupation increased to 68% as workers returned to “hybrid work” in office workplaces, on average, three days a week (De Smart et al., 2021). However, on 26 June 2021, Greater Sydney (including Wollongong and Shellharbour local government areas in the Illawarra region) was plunged into a second lockdown, with office-based workers again displaced. By September, office occupancy rates in the City of Sydney were just 4% (Property Council of Australia, 2021). WFH continued as the primary form of labour for many office workers in the Greater Sydney area, with a wholesale return only resuming in late February 2022.

Our investigations focused on WFH in Wollongong, the primary urban centre in the Illawarra region, and were conducted during the 2021 lockdown. Several factors made Wollongong an ideal place from which to explore lived experiences of intensified WFH. First, in recent decades the city and wider region have undergone substantial economic restructuring, transitioning from an industrial labour market toward an economy dominated by employment in knowledge-based service industries (Warren, 2019). Second, Wollongong has become one of the top sea change destinations for residents migrating out of Sydney. Such out-migration became an increasing trend through the 2020–2021 COVID-19 lockdowns (Needham, 2021). Third, through population and demographic changes, the city has become more deeply connected to central Sydney’s office-based economy. Wollongong and the Illawarra absorbed significant amounts of WFH among office-based workers displaced from the CoS during lockdowns; this included regular commuters (>4000 daily) who transitioned to WFH in lockdown and others relocating to the region when office-based work ceased (Deloitte, 2021a). Fourth, Wollongong’s coastal amenity has spurred significant price increases within the city’s housing market, for buyers and renters alike.5 With many younger people in the Illawarra renting, often in share house arrangements to help manage housing costs, the capacity to alter spaces in the home to accommodate intensified WFH can be limited. These socio-economic factors, combined with the substantial proportion of people employed in producer and professional service firms (28%), made Wollongong and the Illawarra ideal sites for the place-based examination of worker’s lived experiences of WFH during the pandemic.

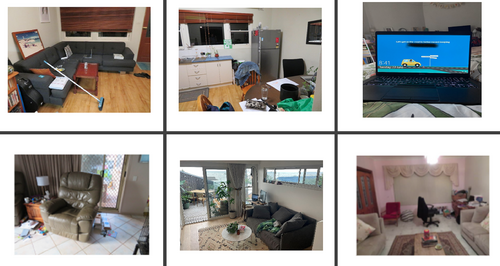

We engaged a feminist qualitative methodology to explore lived experiences of pandemic-related WFH and the many forms of labour performed as people negotiated tasks and income-earning from home through workers’ voices (see Reid-Musson et al., 2020). We recruited office-based knowledge workers engaged in WFH during the lockdown to explore the practices, structures, attributes, materialities, and experiences through which the time-spaces of WFH were shaped. The methods were founded in feminist commitments that knowledge creation is situated, embodied, material and grounded in the politics of place (Johnson & Madge, 2021). Ethics approval for the research was granted by the University of Wollongong’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2021/180). Data collection involved four stages: (i) desktop analysis of media and grey literature on COVID-19’s transformation of office-based knowledge work; (ii) semi-structured interviews, some with home tours, addressing where and when participants worked in their homes and how home spaces and work spaces interacted in 21 interviews of circa one hour with seven home tours (Table 1);6 (iii) time-space diaries with optional photographs conducted over a week of lockdown WFH, with participants recording details about their work space, tasks and activities, experiences of interruptions and disruptions to paid work (13 diaries and 40 + images); and (iv) follow-up semi-structured interviews with photo-elicitation based on participants’ time-space diaries (10 follow-up interviews). We sought to move beyond the textual to understand participants’ WFH experiences and capture the emergent, relational, overlapping time-spaces of WFH.

| Pseudonym and gender | Age (years) | Yearly income* | Tenure and home attributes | Industry and role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olga (F) | 18–25 | $52–$65k | Rental apartment, shared (2) | Government agency, Consultancy |

| Henry (M) | 18–25 | $104–$156k | Own house w/partner | Financial, tech development |

| Tiberius (M) | 26–35 | $104–$156k | Own house, w/partner and 1 child <5 | University, academic |

| Simon (M) | 56+ | $104–$156k | Rental house, partner and 2 children <12 | Education, primary schools manager |

| Henrietta (F) | 18–25 | $52–$65k | Rental house, shared (3) | Public service, graduate |

| Xavier (M) | 18–25 | $65–76k | Rental apartment w/ partner, then family home w/partner | Public service, client engagement officer |

| Albert (M) | 18–25 | $52–$65k | Rental house, shared (4) | Consultancy, environmental consultant |

| Mary (F) | 18–25 | $52–$65 | Rental house, shared (3) | Financial, digital marketing |

| Oliver (M) | 26–25 | $38–$41.6k | Rental house, shared (3) And Mother’s home | University, academic |

| Bridget (F) | 26–35 | $78–100k | Rental studio, alone | University, academic |

| Wylie (M) | 26–35 | $65–$78k |

Rental house, shared (5) Rental studio w/Partner |

Insurance, tech support |

| Kurt (M) | 18–25 | $41.6–$52k | Rental apartment, shared (2) | Creative digital, marketing |

| Matthew (M) | 18–25 | $65–$78k | Rental house, shared (4) | Financial, tech development |

| Adrian, (M) | 26–35 | $65–$78k | Parents home, separated flat w/partner | Consultancy, environmental consultant |

| Brittney (F) | 18–25 | $65–$78k | Mother’s home w/mother and sister | Digital content creation and marketing |

| Jelana (F) | 46–55 | $104–$156k | Own home, w/partner and 2 children <18 | University, academic |

| Valery (F) | 56+ | $33–$41.6k | Rental apartment, alone | Publishing, research journal editor |

| Grace (F) | 36–45 | $65–$78k | Own house, with partner and one child under 12 | Public service, policy implementation guidelines |

| Rafael (M) | 46–55 | $182k+ | Own home, w/partner and 3 children 18+ | Security software, Asia Pacific manager |

| Sue (F) | 56+ | $104–$156k | Own house, w/2 children 18+ | Insurance, area manager |

| Glenn (M) | 56+ | $104–$156k | Own home, w/partner and 1 child over 18 | Public service, digital program implementation |

- * Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/research/2021-census-topics-and-data-release-plan.

Initial stages of the research were conducted face-to-face just before the second lockdown. However, at the onset of that lockdown, most of the remaining research occurred via Zoom. Although this development prevented the opportunity to generate data directly in situ, Zoom offered a platform to generate rich, fine-grain understandings of participant experience. Rather than presenting an impediment, participants’ and researchers’ familiarity with Zoom allowed online interviews to become a window into the everyday realities of WFH. Lockdown also meant we had limited capacity to explore what Blunt and Sheringham (2019, p. 829) refer to as “the home-city geographies” of WFH, to capture how WFH practices sit within “the interconnectedness and porosity of urban domesticities and domestic urbanism.” The role of urban space beyond the physical bounds of the home in WFH experiences was outside the remit of the research, constituting a key vector for further study.

The following analysis begins with a series of vignettes fashioned through narrative analysis of participant diaries, photographs, and interview material. These provide an empirical illustration of the variegated time-space realities produced as the rhythms and routines of pandemic WFH shaped the home materially and imaginatively (see Gorman-Murray, 2013), and the paid and unpaid labours of life’s work intersected. Following the vignettes, we turn to analysis of participant interviews and insights from home visits, investigating workers’ agency to orchestrate these intersections and the time-spaces of WFH they produced. We attend to how this agency is conditioned unevenly by gender and the socio-materialities of home, shaping uneven experiences and geographies of WFH.

4 ORCHESTRATING WFH TIME-SPACES: RESHAPING HOME AND WORK

Here, using a series of participant vignettes, we sketch the variegated spatio-temporalities of paid labour that emerged in pandemic WFH, each differently interwoven with the home as individuals navigated their roles and responsibilities in specific material and social contexts. We adopt a conceptualisation of time-space, common in geographical thought, as interconnected and mutually constitutive (Liu, 2021; May & Thrift, 2001). We also draw on relational scholarship on the home that understands time-spaces as defined by material, abstract, and social factors (Blunt & Dowling, 2006; Easthope et al., 2020).

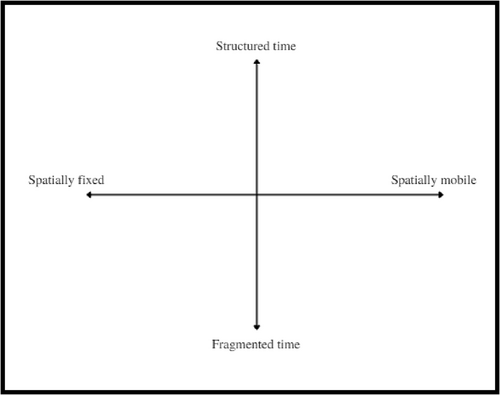

The variegated time-space configurations displayed by participants are interpreted across an intersecting continuum from structured to fragmented temporalities and from fixed to mobile spatialities (Figure 1). The continuum recognises the conditioning role of time in the constitution of space (and vice versa) through understanding time-space as “multiple and heterogenous experiences of social time that are bound up with spatial practices and imaginaries” (Liu, 2021, p. 343). On one end of the continuum, WFH time was shaped in linear, structured terms and, on the other, in a more open and fragmented way. For participants, structured time was tightly organised and linked to the temporality of paid work. Meanwhile, fragmented WFH time was more receptive to change and flexible accommodation of temporalities other than those of paid work. Likewise, space was understood as constituted by materiality, embodied relationships, and diverse labour. Workers’ everyday WFH practices ranged from demarcating a relatively fixed space for doing paid duties to being mobile across the home, occupying spaces that may simultaneously be put to other uses.7 As participants worked-from-home, space was shaped not only by the materiality of the home but also by social relations and imaginaries (Blunt & Dowling, 2006). The multiple spatial intersections that created participants’ experiences reflected how time-space—even at the intimate scale of the home—is not fixed by can be open, fluid and capable of multiple uses (Massey, 1995) (see Figure 2). This conceptualisation points to participants’ potential (and differentiated) agency to reshape the WFH experience. The following vignettes demonstrate the variety of time-spaces created by research participants through their different experiences of WFH.

4.1 Tiberius: Fragmented time and mobile space

Tiberius,8 a 26- to 35-year-old father of one in a heterosexual relationship, is an academic employed by a CBD-based university who lived in a leafy Illawarra suburb. The boundaries of his paid labour time-space were not readily definable: He did not go to his desk to begin his day, nor confine his work to a 9 am–5 pm schedule. Instead, Tiberius was mobile across three main spaces of the home, which he called his “Holy Trinity.” Work time was fragmented into blocks interspersed between paid labour and caring labour. His choice of space was primarily dictated by the type of paid labour he was conducting. For example, Tiberius recorded lectures in the most “office-like” space in his home where he projected a professional digital image. Yet it was also shaped by the temporality of his young daughter’s afternoon sleep when Tiberius seized the opportunity to complete tasks that required sustained concentration, such as recording lectures and reading academic texts.

Time-space was rendered mobile as Tiberius completed paid labour duties in different spaces of the home, defined by the nature of the work, the materiality and the presence of others in the home. In the evening, he undertook work planning and replied to emails from a lounge chair in front of the television. Paid labour blended in with mundane aspects of home life. As Tiberius put it: in WFH, “the working day is a lot more porous. It has a way of kind of seeping into things because I’m … less applying myself consistently, I suppose. Whereas if I’m in a boring office, I just sit there and do whatever I’ve got to do there.” The spatial fluidity in where work was performed mirrored the porosity of time and its openness to social needs outside of paid labour.

Throughout the day, Tiberius interrupted paid work to play with his daughter, prepare meals, and shop for groceries. Work was not simply categorised as paid labour but more broadly as life’s work inclusive of the maintenance of home spaces and care for others (Reid-Musson et al., 2020). Tiberius’ WFH experience reflects Massey’s (1995) careful unpicking of the dualistic separation of home and work. His paid labour and unpaid care work were interspersed across the time-space of the home, each shaping the other (Dutta, 2020). Importantly, WFH did not preclude this, and Tiberius viewed it as a valuable opportunity to spend more time with his daughter. Engaging with the organic relationality between time, space, and the embodied worker (Easthope et al., 2020), Tiberius’ experience revealed WFH in the pandemic as an opportunity for the productive reconfiguration and integration of home and work. Rather than necessarily denying the care labour that underpins home as a site of (re)production (Jenkins & Smith, 2021, p. 25), Tiberius constructed and embedded himself within a time-space of WFH that prioritised participation in a home life from which he derived considerable joy.

4.2 Brittney: Structured time and fixed space

Brittney, an 18- to 25-year-old woman, resided in the family home with her mother and sister. She had worked as a production manager in social media and marketing for a Sydney-based firm for over two years, creating, coordinating, and executing marketing campaigns. Brittney’s work days revealed readily definable times and spaces of paid labour, determined by discrete physical and temporal boundaries. Beginning each workday at 8 am or 9 am by checking emails, she then commenced other tasks such as attending meetings with a work team. Brittney worked from a bedroom office desk unless she was on her regular afternoon walk, when she took her phone to address emails as needed. Brittney finished work between 5 pm and 6 pm, depending on what tasks required daily completion. Like her work time, Brittney’s work space was defined by a lack of porosity to other needs and interests within the home. These were not allowed to shape her paid labour regime. WFH took precedence and shaped the dynamics of Brittney’s home time-space from 8 am to 6 pm, when paid labour duties were the primary influence (Blunt & Dowling, 2006).

Nonetheless, although Brittney’s paid labour was more fixed spatio-temporally, boundaries were still created in line with the rhythm of her workday. Brittney reconfigured the home’s materiality to align “with … dynamic work-related needs” (Goodwin et al., 2021, p. 3). For example, Brittney created a defined work-space in her bedroom to accommodate daily tasks, tidying up the room, making the bed, and creating a “Zen” atmosphere so that she did not feel like she was “living in it like a pig.” At other times, Brittney sought to re-create a more homely, comforting space. Turning off the laptop and work notifications, Brittney moved downstairs to the family area of the home. At this point, she did not engage with social media as required during her paid labour.

Echoing the arguments of feminist geographers, Brittney revealed the interdependency of home and work spheres with paid labour time-spaces formed by socio-spatial relations. She created time-spaces of WFH that were mindful of the home as a work-space shared with others, specifically her mother, Sue. As embodied labourers, Brittney and Sue negotiated paid work and familial relationships within the spaces of the home, seeking quiet and uninterrupted time-space for performing paid labour. Their negotiations reveal the valorisation of paid labour in the home, as the demands of work consumed spaces and reshaped areas of the home in terms of mobility, intimacy, noise, and unpaid labour (Blunt & Dowling, 2006). Brittney shared how she “sticks to her room the majority of the day” as her mother attended meetings that needed a quiet, interruption-free setting. For Brittney and Sue, negotiating the intimate mother/daughter relationship was a critical element of the WFH process, allowing time-spaces for productive paid labour to be created and maintained. Although this reworking was relatively harmonious, made possible by the compatibility of Brittney’s and Sue’s work needs, their situation raises questions about the co-constitutive modalities of social relationships and the power geometries that create the time-spaces of WFH (Meah, 2014). In the following vignette, the dynamic time-spaces of WFH were experienced very differently.

4.3 Simon: Fragmented time and spatially fixed

Simon, a father of six children who is aged in his 50s, lived at home with the two youngest and his wife. He worked as director of primary education for a non-government school with campuses dispersed across New South Wales. Prior to COVID, Simon’s work involved significant travel. However, in lockdown, he predominantly worked from a desk at home between 7:30 am and 4 pm. His work space was positioned within a larger room that served as a dining area and secondary lounge room, except for when he answered emails late at night on the couch using a smartphone. Closing two doors sealed the room off to the adjacent lounge and kitchen areas, which Simon often did as other family members used those spaces. For regular meetings requiring professionalism, Simon desired peace and quiet. To a degree, Simon synchronised his paid labour with the needs of his children, enabling him to perform care labour, including school runs and cooking some meals. Although care labour was shared with his partner, Simon acknowledged he was “less active” in his parenting than his paid work. He relied heavily on his partner’s unpaid care labour to enable a productive WFH experience: gendered labour that is not readily visible in capitalist labour markets (Jenkins & Smith, 2021).

Equally significant, Simon’s WFH time-space was fragmented due to his accommodating the unpaid labours of the teachers he supervised, shaped by the “ebb and flow” of their day. Simon’s colleagues emailed questions late in the evening because “many of them [teachers] are young, they’ve got young families.” Illustrating the diverse temporalities that shaped the time-spaces of the home (Blunt et al., 2020), Simon was able to alter his paid labour practices to meet colleagues’ needs. These WFH experiences emphasise how the home is a multiscale site comprising socio-spatial relations that stretch beyond its immediate time-space (Blunt & Dowling, 2006). Simon demonstrated how a wide range of seemingly mundane social relations are central to any labour process, extending to understanding experiences of WFH among knowledge workers (Massey, 1995). The fluidity in the time-spaces comprising WFH is illustrated in the final vignette.

4.4 Henry: Structured time and spatially mobile

Henry, aged 18–25, worked for a financial institution and led a team developing digital technologies for financial services. He lived with his partner, Sarah, in a home they owned together. Henry’s WFH time-space was spatially mobile yet tightly structured temporally as he worked for long blocks of continuous time between 8 am and 6 pm. Henry’s experience reflects how knowledge work, as an embodied social process, enables paid labour to go where the worker does (Gray et al., 2017). Although Henry reiterated how WFH unravels the neat separation of work and home (Reid-Musson et al., 2020), he navigated the diverse demands of paid labour by seeking to maintain home as a place of belonging, intimacy, and comfort.

At the forefront of Henry’s WFH experience was spatial flexibility. Henry had the space to dedicate a room in his home for an office and could move freely between the kitchen table, couch, and outdoor area. Henry worked in any part of the house conducive to the nature and intensity of the task at hand. For instance, when engaging with stakeholders outside of his immediate team, he would “make sure I’m sitting at my desk so I can show that I’m paying attention.” As a knowledge-based, embodied social process, the nature of Henry’s work meant paid labour could move with him, quite literally (Gray et al., 2017). However, Henry’s work often involved declining loans and talking customers through difficult financial situations such as closing down a business. Overhearing these discussions proved stressful and emotionally “difficult” for Henry’s partner Sarah. In response a clearly defined time-space was created for Henry’s paid work where certain tasks were done in an enclosed office space. Having an area of the home available to be dedicated to paid labour helped address another household member’s sense of belonging and comfort at home (Blunt & Dowling, 2006).

4.5 Variegated space-times of pandemic WFH: Co-constituting work, home, and worker

The four vignettes above reveal the variegated time-spaces of pandemic WFH created at the intersection of home and urban spaces, paid and unpaid labour, as embodied workers (differentially) shaped the spatio-temporal practices of paid work within individual work-home-spaces. Tiberius reiterated the argument of feminist scholars about the sheer presence of unpaid work, illustrating how paid labour duties are shaped around and through care labour for family members. Brittney and Henry exemplified how the inclusion of paid labour in the home space affected the performance of power geometries, including with other household members. Simon, meanwhile, revealed how attention to co-present bodies, household relationships, and the labour required to maintain the home is vital for understanding the multiple forms of labour that enable WFH. Overall, the vignettes reveal that WFH is not an experience merely constituted by labour confined to paid roles and responsibilities, nor is it simply a matter of finding a space to do paid work. Consistent with feminist arguments, we show that work, home, and worker shape one another in the reconfigured geographies of office-based knowledge work.

The vignettes make explicit how each of the iterations of WFH time-space required orchestration by working bodies, as both work and home were reconfigured by the rhythms, routines, and demands of accommodating WFH. However, equally crucial, though more implicit, in these vignettes is the different degrees of agency workers have to shape WFH experiences, including the orchestration of time and space for paid work. Thus we now turn to the question of agency in the context of different experiences of WFH.

5 DIFFERENTIATED AGENCY: GENDER AND SOCIO-MATERIALITY AND THE ORCHESTRATION OF WFH

This section draws the question of agency to the surface. Specifically, we examine worker’s differentiated capacities to shape positive experiences of WFH. Shifting our focus from individual vignettes that illustrate the dynamic orchestrations of time-spaces to accommodate WFH, we turn to focus on two key vectors that conditioned agency in our research: the recurrence of gendered labour practices around life’s work and the socio-material structures of home that shape worker’s capacities and affordances for accommodating WFH. Both factors, we argue, have significant implications for the post-pandemic evolution of (uneven) geographies of hybrid work.

5.1 Gendered working bodies

Drawing on FEG’s emphasis on working bodies and workers as embodying multiple, intersecting social identities (McDowell, 2014), here, we consider how the agency to shape geographies of WFH are conditioned by the reinforcement of gendered divisions of labour in the home. However, we also point to opportunities for the lineaments of these divisions to be reworked through the emergence of WFH, particularly through amplifying the space for male care work.

The vignettes show how a range of social factors shape individual experiences and agency in the context of WFH. Tiberius’ vignette was about how paid and unpaid labour were folded into the same time-spaces, illustrating how the embodied individual is a key site from which traditional gender roles can be reworked (Jenkins & Smith, 2021; Massey, 1995). However, other experiences reflected emergent research findings that suggest WFH can reinforce gendered dualisms, patriarchal relations, and uneven practices of paid/unpaid labour (Cockayne, 2021; ILO, 2021). This is because women workers remain constrained by their continued disproportionate responsibility for emotional care and mental labour as organisers and regulators of the home. Women continue to find their time “more restricted from childcare and household chores” as they prioritise the needs of children and other family members (Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2020). In our study, the home was a site where women participants did most of the unpaid work necessary to sustain social life. WFH did not so much challenge gendered divisions of labour in households as reinforce inequities, underscoring the reality that “struggles over work take place at home” (Carswell, 2016, p. 134).

My kids (two teenage children) do a lot of sport and training. I will take one of them during the day somewhere. But I know I have a meeting at the same time. I will sit in the car, set myself up and do that meeting in the car. And I’ve done that a lot over the last three weeks. Just so … their sport schedule isn’t disrupted.

We’ve got a really good balanced family environment in terms of making sure that we share everything equally, but I think it’s probably yeah, I’m at home (now), so okay, I’ll just make that I get that washing done, and that food ready for dinner, and everything’s ready … Like, okay, everything’s done. You feel better, but (you) tend to lump it all onto yourself.

Jelena’s experience of WFH was evidently patterned by a gendered division of labour in which she did most of the unpaid work at home on top of managing her paid work. By contrast, Jelena’s husband did considerably less unpaid work at home (ILO, 2021; Reid-Musson et al., 2020). Jelena absorbed most of the work of social reproduction at home to sustain the time-space of her paid labour. But in the process, divisions of labour across the wider familial household remained uneven.

I’ve got to say, from my first year of working from home, I did none of that sort of stuff, like, I really was so dedicated to (paid) work … But I guess I have relaxed over time with that. My husband, it used to drive me nuts, but he’d get home from work and go, “you have not emptied the dishwasher, or hung the washing out, like what’s going on.” And I’d be like “I’ve been working [both laugh]”!

Jelena’s and Grace’s unpaid labour sustained their homes, households, and the spaces that accommodated WFH. Yet their reflections also underlined the stubborn gendered divisions of work, which persisted and were even reinforced through pandemic-induced WFH. Both women made compromises to accommodate paid labour around family (James, 2014). These insights articulate the importance of understanding different bodies, including gendered bodies and their respective degrees of agency in orchestrating the emergent reconfigurations of home, work, and worker. An argument made by Elson (1999, p. 611) that “labour markets are gendered institutions operating at the intersection of the productive and reproductive economies” remained true through WFH. As McDowell (2015) powerfully illustrates, during episodes of major economic restructuring such as that induced by the global pandemic, women often experience continuity in their working conditions and divisions of labour rather than systemic or progressive change. FEG helps uncover the uneven experiences of pandemic WFH, including how inequities and oppressive structures that differentially shape workers’ agency are reproduced and reinforced rather than reorganised. These findings have important implications considering the longer-termed emergence of hybrid working patterns.

Importantly, however, the experience of research participants who resided in shared households with different demographics, and who were less tied to traditional gendered divisions of labour, revealed a different inflection on worker agency. In such social contexts, we found the potential for WFH to amplify the space for men’s care work in the home and, relatedly, support the capacity for individuals to reconfigure gendered divisions of unpaid labour around WFH.

I’ll do a few chores while I’m at home, like chuck washing on and, like, if I’m taking a break to have lunch or whatever, I’ll sweep floors and stuff, just because I’m there and idle … I don’t know if you have seen how the boys clean but … [pulls a face]

Oliver cleaned and did unpaid care duties during the working day to maintain cleanliness at home, which was unlikely to be achieved otherwise. Similar experiences were shared by Matthew, who also lived in a rental share house with other men and performed more unpaid labour than his housemates. Oliver and Matthew expressed alternative masculine identities within their homes in undertaking unpaid care labour. Drawing on Gorman-Murray’s (2013) study of men’s embodied engagements with home, domesticity, and care work, the experiences Oliver and Matthew had indicate the differential possibilities for embodied individuals’ to exercise agency and reconfigure essentialist assumptions about gendered labour through the affordances of WFH (McDowell, 2015).

The multiple identities of working bodies—whether as a mother or a young man reshaping norms of masculinity—shaped the level of unpaid labour in the home undertaken as part of the pandemic WFH experience. To echo James (2014, p. 18), the different experiences of WFH we uncovered affirm the need for further attention toward the “gendered identities, varied responsibilities of care and personal-life interests beyond the workplace,” particularly as WFH becomes entrenched as part of hybrid forms of work into the future.

5.2 Home’s socio-materialities

In this final empirical section, we examine how the socio-materialities of home differentially shape WFH experiences, informing the capacity for workers to accommodate additional paid work in the home. In focusing on working bodies, tasks, and spaces we continue to follow feminist perspectives that conceptualise home and work as co-constitutive (Reid-Musson et al., 2020). In particular, the physical size of the home, the material affordances of housing tenure (particularly home ownership), and the related socio-materialities of the life stage emerged as consequential and worthy of deeper investigation.

(I work) in my kitchen, in front of my fridge, which also is a bit weird when I’m on professional calls with say a department … a little bit awkward. So sometimes I work from the couch, which is a little bit more comfortable. A better background. Definitely.

Olga’s experience mirrored an acknowledgement by Nansen et al. (2011, p. 711) that a “particular dining room, kitchen, or bedroom each provides a material context that interpolates certain routine performances and shapes their execution. Importantly, rooms, furnishings, technologies, and possessions frame the performance of daily life.”

My husband insulated this office, it’s probably the warmest room in the whole house. And then we got a heater in here and stuff. It’s super comfortable. The office is really set up well with printers and shelving and everything I need.

If I was to work from the lounge room, then I wouldn’t want to go out there after work because I’d be so sick of it by then. And if I worked in my bedroom, it’d be the same thing: that’s ruining my sleeping space. So that’s the downside of having such a small house. I’m still trying to balance out the working in my kitchen and then finishing work and spending time in here doing healthy cooking.

The materiality of Olga’s home shifted for paid labour so drastically that she found it difficult to transition back to a homely space free from the connotations of doing paid work.

Housing tenure was the other key feature of home that influenced individuals’ agency to orchestrate the work-home-space to their liking within the Illawarra. As a socio-material relationship, tenure fundamentally conditions the power geometries that situate the home and householder (Easthope et al., 2015). Feminist writing on home and housing has highlighted how tenancy (re)produces differentiated time-spaces and social relations (Dufty-Jones, 2017). Our research, for example, reflected the tendency for younger people in the Illawarra to rent and work in spaces that served many social functions (Goodwin et al., 2021). During 2021, the median house price in the Illawarra also exceeded AU$1 million for the first time with a significant contributor to price growth being pandemic-induced outmigration from Sydney (Fernandez, 2021). A housing affordability crisis in the Illawarra meant younger participants in their 20s were almost exclusively renting and often living in smaller dwellings that lacked defined office-type spaces. As such, participants frequently moved around the home to work, juggling to accommodate WFH while being cognisant of other housemates’ needs. For instance, Kurt, an 18- to 25-year-old in digital marketing, lived in a small, rented apartment with another housemate. He had a small desk in the living room that he used when available, but his home was too small to allow for a dedicated work-space. In his WFH experience, Kurt had to negotiate different objects, noises, distractions, and material co-presence of other bodies (Goodwin et al., 2021; Holton, 2016). These features of home life, thrown into proximity in smaller homes with co-present housemates and workers, intermittently disrupted Kurt while “at work.”

I was really hesitant to bring this working from home arrangement, like into my bedroom. But because I live in such a small house … three housemates and me, like, I don’t really have anywhere else I could put it.

Henrietta had no choice but to co-locate her living and working space. Her experience was also shaped by her renting in a share house and the proximity of housemates, induced by the dwelling size. Henrietta’s ability to shape spaces within the home to accommodate paid work tasks was restricted to her bedroom. In homes with limited physical space, the intrusion of paid work (including computers, folders, and equipment) affected how participants experienced WFH in shared rental accommodation. More negative experiences and pessimistic views of WFH were strongly associated with the material space of home and the “various time-space routines” of others who lived there (Goodwin et al., 2021, pp. 5–6).

… when COVID hit, it was an opportunity for me to WFH, because I’m in a good position being older now. And the kids are on their way … and our house is equipped for it. I have a whole room here that I can use. We don’t use it for anything else.

For Glenn, paid labour was less influenced by the socio-material demands of care work for dependent family members or living in a share house. As such, Glenn was at liberty to reorganise the space of his large home.9

Feminist geographers have long anchored analyses of work to gendered bodies and wider relations of social difference, drawing out connections to employer organisations, institutions of the state, and wider spaces of the city (McDowell, 2016; Werner et al., 2017). Our analysis in this section has shed light on how, in the emergent context of pandemic WFH, gender and particular dimensions of the socio-materalities of home that reflect social differences (dwelling size, tenure, and life stage) become vital contours of how home and work are reconfigured. Ultimately, in the context of WFH, we argue it is crucial to acknowledge that workers have different capacities to shape and utilise spaces of the home to do paid work. The differentiated agency of workers is significant for understanding the gamut of experiences regarding WFH and future scenarios where there is increased hybridity in the time-spaces of work and employment.

6 CONCLUSION

COVID-19 and related lockdowns resulted in a rapid and widespread intensification of WFH. This analysis in the Illawarra region has revealed how complex interactions between work, home, and (embodied) knowledge workers shaped the geographies of WFH that emerged through the pandemic. In particular our analysis, underpinned by qualitative methodologies, sheds light on how the home, as a material site shot through with different socio-spatial relationships, diverse materialities and meanings, shaped the time-spaces of WFH and, relatedly, how the rhythms and routines of WFH shaped the home (see also Goodwin et al., 2021; Nansen et al., 2011).

Our findings thus reinforce FEG’s assertion that paid work never enters a labour-free zone called the home. Rather, a complex array of “life’s work” already revolves around the home, including care for children and intimate social relations with family and housemates (cf. Hall, 2019; Mitchell et al., 2004). The experiences of workers highlighted above also reinforce geographies of home as relational, embedded in manifold socio-materialities and imaginaries. We make two key contributions by combining the relational theoretical insights of FEG and geographies of home scholarship. The first is to reveal the variegated time-spaces that emerged in pandemic WFH within the socio-materialities and socio-spatial relations that constitute home. In navigating WFH, the relationships of home were reconfigured to support the capacity to perform specific paid tasks and responsibilities. The second contribution is to recognise and begin to disentangle the differentiated agency of embodied workers to orchestrate variegated WFH time-spaces and the power geometries in which they are embedded (Carswell, 2016; Dutta, 2020; Gorman-Murray, 2017). Our analysis has revealed the multiple forms of labour entailed in managing arrangements to do with WFH, including how embodied workers’ attempted to craft time-spaces for paid work with differentiated abilities to do so in ways that created a positive WFH experience (Goodwin et al., 2021). Here, we acknowledge that the agency of workers was conditioned by gender and the socio-material relations that produce home.

As we enter a post-pandemic world, some corporate employers are heralding WFH as a success and implementing more permanent remote working policies. Other global firms, including Tesla and Apple, are demanding workers return back to centralised office spaces (Ward, 2021). With 75% of Australian workers wanting to continue WFH two or more days per week (Productivity Commission, 2021), “hybrid work” is likely to become established in Australia’s work and employment landscape. This paper provides valuable insights into the benefits and challenges of WFH arrangements relevant to hybrid work futures. Our findings point to important questions around differentiation in this emergent landscape, its spatio-temporalities and power geometries. We close by briefly articulating three questions we see as priorities for further research as the contours of hybrid work take shape.

A useful starting point for research going forward is the recognition that WFH time-spaces do not materialise out of nowhere. They emerge as a variegated temporal and spatial process from the complex intersection of space, time, socio-material relations, and power geometries of home and work (Hall, 2019). Widespread, long-term WFH home demands complex orchestrations of workers and employers shaped by these intersections. The socio-material settings of home are central to the conditions in which workers’ labour, and they delimit embodied workers’ agency to shape WFH time-spaces in ways that are important to people’s sense of home. Rather than assume WFH delivers universal outcomes, more research is needed to provide a deeper understanding of its variegated time-spaces and of workers’ differentiated agency to shape these time-spaces. This work will be key to informing workers’ personal choices around WFH and the regulation of WFH by firms and governments.

Second, WFH surfaces how paid labour is constituted and enabled by forms of under-recognised labour (Werner et al., 2017). The WFH workspace is always more than simply a desk in a curated room. It involves the daily negotiation of co-presence, intimate relationships and caring labour performed as home/work intermingle. Our research resonates with emerging findings that suggest widespread WFH could reinforce the continuation of gendered labour paradigms and power geometries and the limitation of women’s agency over “life’s work” (Chattopadhyay, 2021; ILO, 2021). However, it also points to the possibilities for subtle realignment of inequitable relations and power geometries that traditionally constitute home, work and worker. Further research is needed to unpack the conditions under which opportunities for progressive realignment can be recognised and amplified.

Finally, tenure is likely to be a highly significant socio-material relation that mediates and differentiates agency in the use of the home space for paid work (Goodwin et al., 2021; Nansen et al., 2011). Housing tenure actively shapes workers’ experiences of WFH, particularly in terms of physical space and freedom to remake spaces of the home more conducive to enjoyable work. As “generation rent” makes long-term rental and share housing a reality for growing proportions of the Australian population (Maalsen et al., 2020), the power geometries of tenure need to be a central consideration of WFH and its regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the research participants who shared with us their experiences of their work/home time-spaces during testing times. Thanks are also due to Chris Gibson and Rae Dufty-Jones for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this work, and to the reviewers for their insightful and instructive comments. Thanks are due to the research participants who shared their working lives and homes with the researchers, during challenging times. Thanks are also due to the reviewers and editors, and to the examiners of Emily Ormond’s honours thesis. Their engagement with the paper and constructive comments have helped us refine the paper. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley - University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Wollongong’s Human Ethics Research Committee. Approval number 2021/180. Informed consent was obtained and documented from all participants included in the study.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Although this paper is focused on office workers, we acknowledge the gender-based challenges faced by workers in non-office and essential forms of work, particularly for care-based industries such as general health, child/pre-school and aged care. For these workers, WFH was not feasible as they were required to maintain a presence in a specific workplace, often making them susceptible to COVID-19 infection

- 2 Indeed, FEG is founded on expansive understandings of ‘work’ that emphasise both the embeddedness of work in relationships with the state, employer organisations and institutions, and the diversity of forms that work takes as part of day-to-day life, including reproducing life itself.

- 3 A survey of Australian men and women conducted during lockdowns in 2020 also found unpaid labour in the home grew as access to services diminished and, whereas men increased their unpaid labour hours via increased childcare, women still reported feeling unsatisfied with the division of household labour (Craig & Churchill, 2021). A host of consulting reports has confirmed the uneven gendered impacts of WFH and post-COVID work landscapes, for example Wood et al. (2021) and Deloitte (2021b).

- 4 The City of Sydney refers to the Local Government Area that encapsulates central Sydney and contains the primary CBD office concentration.

- 5 Under several measures, such as median house prices and the ratio of median price to median household income, the city’s property market is one of the least affordable nationally (CoreLogic, 2023).

- 6 Participants were eligible to participate if they worked in their home space, their office or home was in the Illawarra, and they worked in the office-based knowledge economy. The sample recruited included a relatively high proportion of workers under the age of 26, some of whom had been in their jobs for a relatively short period of time. The participants nonetheless represented a diverse range of industries and job types, ranging from graduate public service roles to tech workers in international companies, and a cross-section of life stages.

- 7 Here, we note again that this research was conducted primarily during lockdown conditions. Our participants were largely restricted to their homes and unable to conduct work from cafés, co-working spaces, or other kinds of public spaces.

- 8 Pseudonyms are used for all research participants.

- 9 Of course, owner-occupiers at different life stages may be situated in different social dynamics and opportunity structures. The presence of children at home, multi-generational households and so forth, differentially condition the agency to determine the orchestration of WFH and the mutual reconfiguring of home and work (see Graham et al., 2021).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.