Transboundary river governance and climate vulnerability: Community perspectives in Nepal’s Koshi river basin

Abstract

Frequent floods in the Koshi River have left the Nepalese vulnerable to erosion and recurring inundation—especially those living on the floodplains. The situation is worsening because water flow in the river is highly uncertain, affected by rainfall in the mountains and by climate change, and influenced by the Koshi barrage, which is governed by the Koshi River Agreement, a bilateral river agreement with India. This study addresses how Koshi River governance contributes to the vulnerability of riverine communities in Nepal by drawing upon ideas about vulnerability and vulnerability mapping. A household survey and interviews were conducted in 2015 for a comparative study of people living on two river islands located upstream and downstream of the barrage. Findings remain relevant because of persistent governance challenges and growing climate change effects, escalating islanders’ vulnerability to recurrent floods. The islanders’ vulnerability was produced locally and also shaped by historical, social, economic, political, geographical, and ecological processes occurring at multiple scales. That insight highlights the need to study the broader political economy of hazard production to understand vulnerability in the context of governance.

Key insights

In light of Nepal’s Koshi River’s frequent floods, this article investigates how governance contributes to the vulnerability of riverine communities in the basin. Drawing upon ideas about vulnerability and vulnerability mapping, it was found that communities’ vulnerability was shaped by local socio-economic practices and by multi-scalar political economic processes occurring at different times. Specifically, vulnerability is produced because of irresponsible and unaccountable decision-making and lack of critical and coordinated governance roles.

1 THE KOSHI RIVER BASIN AND ITS VULNERABILITY TO FLOODS

In the monsoon of 2008, a breach of the eastern Koshi River embankment in Nepal killed 55 people, including some in temporary shelters (Ministry of Home Affairs and Disaster Preparedness Network-Nepal [MoHA & DPNet-Nepal], 2011). The breach affected 65,000 people and 700 hectares (ha) of fertile land (Kafle et al., 2017) and created havoc downstream in Bihar, India. The incident was one of the most devastating natural calamities in Nepal between 2000 and 2010 in terms of its intensity of damage to people and properties (Kafle et al., 2017). Nevertheless, floods have continued threatening thousands of Nepalese riverine people almost every year since 2008. In 2018 and 2019 alone, the national government recorded 183 deaths, the destruction of 14,710 houses, and widespread effects on 16,196 families in 418 flood incidences (Ministry of Home Affairs [MoHA], 2019). In 2021, 60 people died, 36 disappeared, and 13 were injured because of floods (Nepal Disaster Risk Reduction Portal, 2021).

There are various reasons behind increasing vulnerability to flood hazards among people in the basin. The first is uncontrollable expansion of settlements on floodplains. Illegal occupation of floodplains in the southern plains (the Tarai) started with malaria’s eradication in the 1950s (Ghimire, 2017). Many poor people from hills and mountains settled on floodplains because of the availability of land, fertile soil, and high crop productivity. The second factor is climate change to which the Himalayan region1 in which Nepal lies is vulnerable because of increases in average temperature (Pörtner et al., 2022). According to Nepal (2016), the average temperature increased in the Koshi river basin between 1960 and 2009 at a rate of 0.014°C/year for the minimum temperature and 0.058°C/year for the maximum temperature. Consequently, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are rising (Shrestha et al., 2017). Hikes in temperatures will cause highly uncertain water flow (Kaini et al., 2021), exacerbating people’s vulnerability on floodplains. But vulnerability can also be attributed to river governance. The river is currently administered by a water-sharing agreement between Nepal and India, the Koshi River Agreement (KRA), signed in 1954 and revised in 1966, but which has not stopped thousands of riverine people suffering from the effects of frequent erosion, inundations, and sedimentation (Chen et al., 2013).

Governance can be defined as the process and arrangements by which decisions are made and implemented … Governance refers not to formal arrangements about how decisions are supposed to be made, but to what really happens. Power fits in here, because power can be thought of as the ability to make (or influence) decision-making and the implementation or enforcement of decisions. (Fisher, 2017, p. 134)

Based on Fisher’s definition, good governance is viewed here as comprising processes and arrangements by which decisions are made responsibly and accountably by, in this case, the governments of Nepal and India in Koshi River governance to reduce riverine people’s vulnerability to floods and climate change. The use of power in making and implementing decisions related to Koshi River governance will also be considered in assessing the quality of governance for such ends.

A brief review of literature on climate vulnerability and its assessment approaches is provided first (Section 2). In Section 3, the Koshi river basin and important environmental issues are introduced and then the methods used to collect and analyse data are explained. In Section 4, insights from findings are considered and those are followed by analysis of policy responses on vulnerability (Section 5). The conclusion (Section 6) provides new insights to the concept of vulnerability that should be of wide interest to geographers and others.

2 VULNERABILITY AND VULNERABILITY MAPPING

Vulnerability refers to susceptibility to harm experienced by an individual, household, or community from exposure to a hazard. According to the IPCC (2014, p. 5), vulnerability is “the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected.” The concept of vulnerability evolved from Sen’s (1981) work on the entitlement approach in the food security literature. Sen’s argument, with reference to food entitlements, was that poverty is not the sole determinant of people’s vulnerability; rather, vulnerability is shaped by other factors that render them poor, including trends in labour relations and markets.

Since Sen’s work was published, scholarship on vulnerability studies has grown in volume, and vulnerability is not viewed as an intrinsic feature of individuals or communities but as a relational concept (Gilson, 2014; Turner, 2016), or what Watts and Bohle (1993, p. 46) have defined as a “multi-layered and multi-dimensional social space which centres on the determinate political, economic and institutional capabilities of people in specific places at specific times.”

This framing of vulnerability emphasises the spatial–temporal-scalar interplay across social, economic, and political processes. Blaikie et al. (1994), Haynes et al. (2022), and Ribot (2011) have suggested that social, economic, and political processes and their complex interactions produce vulnerability. Ribot (2014) has argued the need to study vulnerability’s historical and spatial dimensions to understand its causes and that resonates with my own agenda to revisit empirical work generated in 2015. Jackson (2021) has pointed to the insufficiency of causal research on historical and socio-ecological aspects of individual and social narratives, perceptions, and agency related to vulnerability. In climate vulnerability literature, the relationship between water governance and vulnerability is lacking, and the historical socio-political aspects of vulnerability production and stories and sentiments people and communities hold have been ignored in climate vulnerability analysis.

There is a consensus that climate vulnerability includes the characteristics of a system determined by exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity (Adger, 2006; IPCC, 2007b). The IPCC report published in 2022 (Pörtner et al., 2022, p. 43) defines climate vulnerability as “the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected and encompasses a variety of concepts and elements, including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope and adapt.” Exposure has not been explicitly used in that definition but denotes the necessary condition in which adverse effects could occur (Pörtner et al., 2022). It refers to the potential magnitude and frequency of floods brought about by people’s or communities’ geographical positions and infers that sensitivity is the degree to which people or communities may be affected or harmed by flood hazards (Adger, 2006; Fischer & Frazier, 2018; IPCC, 2007a). The factors that mostly influence sensitivity depend on ecological goods and services for economic benefits and access to resources (Cutter et al., 2009; Fischer & Frazier, 2018). Adaptive capacity refers to individuals’ or communities’ abilities to adapt to change, prevent or reduce potential damages, or cope with the repercussions brought about by exposure and sensitivity to flood hazards (Fischer & Frazier, 2018; McCarthy et al., 2001). Access to resources is an important factor influencing adaptive capacity, among others such as social networks and physical strength, which Elrick-Barr et al. (2022) and Mortreux and Barnett (2017) have called the first-generation assessment of adaptive capacity. Noting people’s adaptation anomalies despite asset ownership, Mortreux and Barnett (2017) introduced a second-generation assessment method, also known as mobilisation capacities, which accounts for household-level factors, including risk attitudes, past experiences, faith in authorities, and competing concerns. Barnes et al. (2020) have expanded the second-generation research to include other factors such as organisation, learning, socio-cognitive constructs, and agency. Elrick-Barr et al. (2022) have proposed a third-generation assessment of adaptive capacity to include mobilisation and transfer of capacities between individuals and groups.

There are also growing numbers of studies on vulnerability assessment or mapping techniques. Chambers and Conway (1992) have developed the Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) that considers five different types of assets, which are natural, physical, human, social, and financial. Hahn et al. (2009) have modified the SLA to introduce a new tool called the Livelihood Vulnerability Index (LVI), which employed multiple indicators to assess three different aspects of vulnerability at a household level: exposure to natural disasters and climate variability; sensitivity determined by access to health, food, and water resources; and adaptive capacity determined by socio-economic status, livelihood strategies, and social networks. Likewise, Pandey and Jha (2012) have introduced the Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI), which also included all three dimensions of vulnerability. The Governance and Climate Vulnerability Index (GCVI) introduced by Jubeh and Mimi (2012) has normally applied quantitative measures, incorporating governance indicators along with other CVI indicators. One of the problems with these approaches, however, has been that they analyse vulnerability quantitatively, ignoring non-climate related factors, the stories and sentiments of people and communities. Thus, they are not flexible enough to consider social, economic, and political causes of vulnerability (Hinkel, 2011; Sapkota et al., 2016).

Studies on climate vulnerability have shown a direct correlation between poverty and climate change impacts; however, other factors also affect vulnerability. Floods affect poor people because they live in poor quality cheaper lands, usually risky floodplains (Hallegatte et al., 2016; Nguyen & James, 2013). Working in the South Pacific, McEvoy et al. (2020) have established that those people who do not have access to critical infrastructure and financial resources, particularly the right to land, have reduced adaptive capacity. Ghimire et al. (2010) have found that Nepal’s hill farmers with access to land had high adaptive capacity to droughts. Where people live has also affected their vulnerability (Thomas et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2003). Vulnerability is also increased by: (a) lack of availability of diversified income options (Gerlitz et al., 2017; Giri et al., 2021); (b) lack of potable water, health, and transportation facilities (Gentle & Maraseni, 2012; Hallegatte et al., 2016); (c) lack of knowledge and dilapidated infrastructure (Giri et al., 2021); (d) reliance on weather-dependent or climate-sensitive incomes (Gentle & Maraseni, 2012; Hallegatte et al., 2016); (e) restricted access to critical information (Casse, 2013; McEvoy et al., 2020); and (f) lack of influential presence in governmental, non-governmental, and local community organisations that can help communities at times of need (Chau et al., 2014; Gerlitz et al., 2017). Nevertheless, Sapkota et al. (2016, p. 62) have argued that the social production of vulnerability to climate change in Nepal’s rural hills has happened because of “multiple interactions of social, cultural, economic and political processes happening at different times and places.”

At larger scales, the IPCC (2014, p. 49) has stated that “challenges for vulnerability reduction and adaptation actions are particularly high in regions that have shown severe difficulties in governance.” Although that statement was made in the context of violent conflicts arising from the impairment of necessary features for adaptation such as assets, institutions, infrastructure, and livelihood options, it applies to other cases of governance. For example, McEvoy et al. (2020) have found a strong link between good land governance and climate resilience planning and practice in the Pacific. However, there is limited research on the linkage between governance and climate vulnerability.

3 RESEARCH WITH THE KOSHI RIVER COMMUNITIES

Applying vulnerability as a relational concept in the context of transboundary river governance, this study uses the IPCC (2007b) definition of vulnerability and considers susceptibility and in/ability of riverine communities to cope with adverse effects of flooding in the Koshi river basin. Thus, it examines communities’ exposure and sensitivity to flood hazards and adaptive capacity to recover from them. In doing so, it explores the relationship between the governance and the hazards in the study area and considers how it affected the communities’ access to safe housing and security, potable water, health and transportation facilities, and food. In turn, it examines how such factors affected people’s socio-economic and livelihood strategies to adapt to and cope with hazards to understand governance-induced vulnerability among the study communities.

3.1 The study site

The research site was located along the Koshi River in eastern Nepal, about 200 kilometres (km) southeast of Kathmandu. Koshi is a transboundary river in the central Himalayan region, originating in China, passing through the breadth of Nepal, and finally draining into the Ganges in India. The Koshi river basin is the largest in Nepal, encompassing about 42% of the total catchment area of the river (Sharma cited in Devkota & Gyawali, 2015). The basin is susceptible to flash and riverine floods, landslides, erosion, sedimentation, and glacial lake outburst floods due to its diverse topography, young geology, intense glaciation, and heavy monsoon precipitation (Shrestha et al., 2010), all of which increase the vulnerability of many riverine communities.

The KRA governs the river. The main aim of this agreement is to control floods, irrigate, generate hydropower, and protect erosion of land in Nepal. After the agreement was signed, works for flood control, irrigation, and erosion protection were carried out under what was called the Koshi River Project (KRP). According to a revision, project leaders were authorised by the government of Nepal to lease for 199 years a portion of the river and adjacent land area, about 10,000 hectares (ha), in Nepalese territory close to the Nepal-India border. Three major structures resulted on the river: a barrage; two flood embankments (respectively 146 and 123 km long) along the river running across the border; and two canals protruding from the barrage for irrigating land in both countries. The barrage and embankments were completed in 1962 and the eastern canal in 1964 (Pun, 2009). As per the agreement, India’s state government of Bihar is responsible for all project-related management, repair, and maintenance works. For the purpose of this article, “the Government of India” will be used to denote both the Government of India and the Bihar Government.

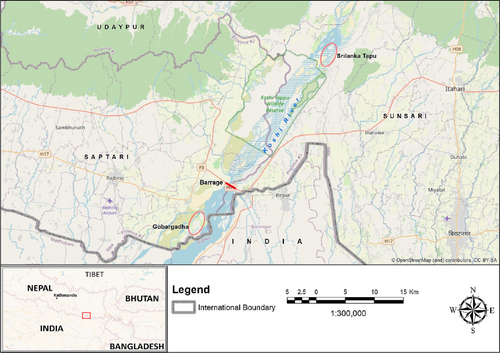

Fieldwork was carried out with Nepali river communities on two river islands (Figure 1). The islands are located in what were then Prakashpur and Gobargadha Village Development Committees (VDCs),2 respectively upstream and downstream of the barrage, which allows for useful comparison of the communities’ vulnerabilities. They were also among the most recurrently flood-affected places along the river. Both islands are surrounded by the Koshi River on the east and west. The main stream of the river was on the east during fieldwork but was flowing to the west of both islands until the early 1990s according to the islanders. During two months of fieldwork in April and May 2015, hundreds of people were living on the islands. (Re)visiting this work at this point is important because it contributes to a better understanding of the islanders’ vulnerability to recurring floods amidst transboundary river governance problems and increasing climate change effects.

The island in Sunsari, located 25 kilometres upstream of the Koshi barrage, is also known as Sri-Lanka Tapu or just Tappu, because of its resemblance to the island nation of Sri Lanka. People started living on the island by clearing forest areas in the late 1940s. During the fieldwork, the land was mostly occupied by the past flood-displaced people and people who migrated from the eastern neighbouring districts.

The island in Saptari (also known as Gobargadha) lies seven kilometres downstream from the barrage and touches the Nepal–India border. During the fieldwork, the islanders included the families of people residing there even before the signing of the KRA, and some new people who migrated from the surrounding areas and from India, while some islanders were living in neighbouring villages due to displacement by severe flooding in the 1990s, who are also included in this study.

3.2 Research methods

A critical pragmatist research approach was followed for this study. “Critical pragmatism appreciates multiple and contingent or evolving forms of knowledge, local or scientific, initial opinion and considered judgement” (Forester, 2013, p. 6). Critical pragmatists argue that truth cannot be absolute, that multiple realities exist, and that knowledge generation takes place where interaction and experience occur (Vannini, 2008).

Following ethics clearances, during fieldwork on the islands, informal key-informant interviews were carried out with locally respected people such as teachers, NGO activists, political and community leaders, and former Village Development Committee (VDC) chairpersons living in what were previously Prakashpur and Gobargadha VDCs. Semi-structured interviews (SSIs) were used to collect data from 93 households selected via a systematic sampling technique. Of these, 30 were from Tappu and 63 from Gobargadha, which also include households displaced from Gobargadha and living in the VDCs of Joginiya (21 households) and Haripur (12 households). Fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted with household heads, based on the information received from the SSIs to gain insights into their life stories and historical contexts and situations related to flood disasters. Of these 15 interviews, seven were conducted in the upstream whereas eight were conducted in the downstream settlements. All in-depth interviews were audio-recorded.

Secondary data and grey literature such as project reports and policy papers on climate change and its impacts in the Koshi river basin were examined. Semi-structured interviews with the household heads were analysed using descriptive statistics for quantitative data and content analysis for the qualitative data. Thematic data coding was done for content analysis using Microsoft Excel. In-depth interviews were transcribed and analysed using narrative analysis. The data were grouped, organised and reorganised, categorised and conceptualised for interpreting the meaning. The findings are presented in the sections below.

4 INSIGHTS FROM THE KOSHI RIVER COMMUNITIES

4.1 Exposure of the communities to floods

Floods on the Koshi River affected communities every year, particularly during monsoons or because of erosion, inundation, and siltation but as well as the destructive flood of 2008, riverine communities from the study site have faced many other disasters.

On Tappu, interviews revealed that flood devastation started only in 1965, three years after the Koshi barrage was built. Some people interviewed claimed blocking natural water flow with the barrage was the reason for harmful floods. People recalled that land erosion due to floods, which started in the early 1980s, completely eroded two wards of Prakashpur VDC, adjoining Tappu, within the five monsoon seasons up to 1985. Some disaster-displaced people moved further west to live on Tappu. Currently, floods erode land from the eastern areas of Tappu adjoining the river every year.

On Gobargadha, people reported that intense erosion began only after the barrage was built but said inundation had existed for a long time. They claimed that floods after the construction of the embankments eroded agricultural land from the western part of the island. Later, in the late 1990s, floods eroded a large area of land and destroyed many houses in the eastern part, displacing many people to nearby villages. Harmful inundation and erosion of agricultural land persistently happened annually until 2021.

Building a protection wall around our island [Gobargadha] would save us from floods. (male, 40–45 years, Gobargadha VDC)

They [usually] don’t inform us when they open the gates [during monsoons]. The barrage is opened [by the authority] whenever they want. Only sometimes when there is an emergency … the police inform us. (male, 50–55 years, Gobargadha VDC)

Climate change also affected the river islanders. According to Paudel et al. (2021), there was an increasing flooding frequency in the river between 1980 and 2018. At least three studies found increasing drought trends and events in the basin in the recent several decades (Dahal et al., 2021; Paudel et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2019), the latter arguing that the trend significantly affected crops and water availability, which was also revealed by islanders during interviews.

4.2 Sensitivity of communities to floods

4.2.1 Access to safe housing and security

Although the KRA envisioned the permanent evacuation of settlements in between embankments, many people have been living in them because the KRP authorities were unable to convince them for safe relocation. The island settlements were typically rural with scattered houses and predominantly in an agricultural setting. On Gobargadha, all the houses were made with mud and reed and were thatched. However, some houses on Tappu were built of wood, which made them comparatively stronger. Either way, houses built on the flood-prone islands were more vulnerable to hazards.

On both islands, the security situation was critical as the Nepal government offices and national law enforcement agencies were absent. Rescue attempts may be jeopardised, particularly in case of flood disasters, as security forces will have to cross the swollen river. Furthermore, the Nepal government had not provided both islands’ residents with access to the national electricity grid. However, the people had solar electricity panels for lighting purposes that were provided by a non-governmental organisation.

4.2.2 Access to potable water, health, and transportation facilities

River islanders in the study lacked potable water and health and transportation facilities. Some were using shared tube wells containing excess iron, which had been marked unsafe by the government. Sanitary conditions were poor due to the lack of toilets, so open defecation on riverbanks. People often faced insecurity of potable water due to contamination in case of big floods or inundations, resulting in sickness and fatality. Health service provision was non-existent or primitive. From Tappu, people had to travel to Prakashpur village across the eastern embankment for any health-related services but travelling to Prakashpur meant using boats at two places to cross the main stream and a rivulet along the way, a journey of between 90 and 120 minutes. Such a situation makes it almost impossible to evacuate immediately in case of an emergency. On Gobargadha, there was a rudimentary government health centre, where all health-related materials and basic medicines were stored in a large traditional bamboo silo. Consequently, residents needed to travel to Hanumannagar town across the river to access health facilities, which would take about 30 to 45 minutes on foot (and by boat during rainy seasons). The absence of these facilities on the river islands made the islanders’ lives hard during floods.

4.2.3 Access to food

Food availability is another important factor determining people’s vulnerability to hazards. The islanders’ main source of food was agricultural produce, mainly rice, wheat, and lentils. Although all the households were engaged in farming, agricultural production was insufficient for the whole year. On Tappu, about 57% of the population was food insecure, whereas it was only 40% on Gobargadha. The main cause of food insecurity was their reliance on the non-irrigated risky land. Food insecure households had to buy or borrow food from their neighbours or relatives. They had to leave the islands to obtain food as there were no established marketplaces, increasing the risk of food shortages during disasters.

4.3 Adaptive capacities of the communities

4.3.1 Socio-economic situation of the communities

People’s socio-economic condition is vital in gaining easy access to resources, determining their ability to cope with and adapt to disasters. The survey showed that the islanders had low socio-economic status than those living outside the embankments. Many islanders were poor, not being able to meet their expenses. About 47% of the Tappu households had insufficient income to meet their annual household needs, while it was about 59% on Gobargadha (92% in Joginiya and 37% on the island). To address their unmet needs, they employed several strategies, including borrowing at high interest rates from informal sources such as family and friends (common) and formal sources such as cooperatives and banks (few).

The main asset for the islanders was agricultural land, as access to land benefits them in several ways. First, they can farm and grow their own food; second, they can build houses permanently; and third, they get access to basic amenities provided by the Nepal government such as national electricity grid and the piped-drinking water. The government denies people access to such facilities without a land ownership certificate, necessitating land ownership.

On both islands, people secured land access in different ways, such as buying privately, occupying public land, and leasing.3 The survey showed that only 35% of the surveyed Tappu households owned land privately, whereas 65% cultivated public land. Private land ownership for the Tappu residents means they became capable of buying land elsewhere, safe from floods. A Tappu resident (anonymous male, aged 55–60 years) was able to purchase land in a neighbouring village away from the river by selling some cattle and agricultural produce. However, moving to a safe location was a dream for many islanders, as a Gobargadha resident (anonymous male, aged 50–55 years) remarked, “We lack capital to go out from here. We can’t afford to buy enough land [outside] for us.” Besides, the Tappu residents also traded public land they occupied, mostly the land adjoining the river. The very poor islanders bought the flood-prone cheap land to erect temporary shelters, increasing their vulnerability to floods. On Gobargadha, only a few people occupied public land (23%) because many received ownership certificates for their previously occupied public land in 1979 after it was declared a Village Panchayat.4 As the land was mostly free or in-expensive, some residents from both islands shifted their houses towards the back several times whenever the floods washed them away. A Joginiya resident (anonymous male, aged 45–50 years) recalled doing so 20 times.

4.3.2 Livelihood strategies

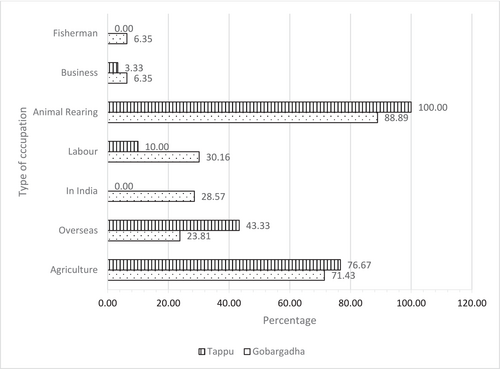

From the survey, islanders’ economic activities portrayed their vulnerability. Agriculture was the main occupation for about 54% and 66% of the economically active people surveyed on Tappu and Gobargadha, respectively. The people who were in foreign employment such as the Middle East, Malaysia, and India had the higher economic status than the rest. On Tappu, about 43% of the households had at least one person working either in Malaysia or the Middle East countries such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain (Figure 2). Most of them acquired land elsewhere in flood-safe areas with remittances. In contrast, only about 24% of the households on Gobargadha had family members working overseas, and about 29% had family members working in India. More Gobargadha residents were employed in India than Tappu inhabitants because they were nearer India and had relatives there.

Some Joginiya residents had their farming on Gobargadha. One of them (anonymous male, aged 45–50 years) remarked, “During floods, my family live here, but I live at Tappu [Gobargadha] in the recent years. I have to look after my cattle and produce there.”

Almost all Haripur residents were engaged in wage work because of farmland inadequacy. A Haripur resident (anonymous male, aged 70–75 years) said, “Everybody is working here; some as wage labourers; some sell firewood; some sell dried cow dungs; some sell fish.” Tappu residents found it hard to find labour work because of their unaffordability to hire fellow islanders. The islanders lacked income diversification opportunities, limiting their adaptive capacity.

4.3.3 Social networks

The survey showed that some islanders received assistance from other people and institutions during disasters. They received short-term relief assistance from the government and some non-governmental organisations that included essential food and clothes, and boats for crossing the river. Besides, they received help from their relatives, and friends, demonstrating almost non-existent formal community networks on the islands. A Joginiya resident (anonymous male, aged 55–60 years) remarked, “All political leaders give assurance to people during elections, but they don’t do anything afterwards.” Another islander (Anonymous male, aged 75–80 years, Joginiya) recalled borrowing money from local money lenders even though the interest rate was about 36% per annum, instead of borrowing from a bank because, “We need to pay them exactly by the deadline, which is very hard.”

5 KOSHI RIVER GOVERNANCE AND COMMUNITIES’ VULNERABILITIES

Vulnerability studies on the global South’s marginalised communities have put forward several dominant narratives in explaining vulnerability. According to Jackson (2021), the narratives are poverty or lack of economic development; global environmental change, particularly climate change; and various development processes that have regularly omitted vulnerability’s historical and socio-ecological aspects, as well as people’s perceptions and stories. Particularly, the climate vulnerability literature has ignored stories and sentiments of people and communities in analysing vulnerability’s multidimensional socio-economic, political, and historical aspects, obscuring the link between water governance and vulnerability. By exploring the Koshi River governance and the riverine communities of Nepal and employing vulnerability concepts and mapping, this article has demonstrated that vulnerability is a relational concept, and the governance has contributed to the islanders’ heightened vulnerability.

The barrage people [Nepalese administration] are only concerned about the customs duty for goods that people bring from Bhimnagar, India. They don’t care about the condition of the barrage. The Indian government also doesn’t care because it has been getting the needed quantity of water from the canals. (Male, aged 50–55 years)

Interestingly, many spurs were built to strengthen and protect the embankments, but the lack of coordinated decision-making and implementation between the Nepali and Indian governments made the islanders vulnerable. Such decision-making resulted in weak planning and practice, resulting in haphazard decisions and/or inaction on critical and urgent issues. For instance, coordination was lacking between the two when making decisions about opening specific barrage gates during floods and unilaterally constructing temporary river barriers. A key informant from Gobargadha happily shared, “The late King visited here [in 1979] and declared it an administrative unit.”, confirming the KRP authorities’ inability to persuade the islanders to relocate elsewhere. Furthermore, they could not collaborate during severe floods, frequently denying critical flood information to Gobargadha islanders giving them less time to prepare for coping and adaptation. The findings are important for policy-makers in understanding the major factors of riverine people’s vulnerability in a transboundary context and devising necessary interventions tailored to their specific needs.

This study also found that the local, national, and international governments’ weak presence and support during the flooding were other causes of vulnerability. The islanders neither got help from the government nor the KRP authorities. Instead, the Indian side exclusively opened the barrage gates on the Nepalese side and built artificial barriers to safeguard land just on its side, affecting the Gobargadha islanders. Besides, the authorities left the islands isolated from the outside world even during non-monsoon times, which was noted from the islanders’ compulsion to drink groundwater tainted with excess iron, a lack of connection to national electricity grid, a lack of proper health, sanitation, transportation, and security facilities. Lack of government assistance in obtaining irrigation and other livelihood support services forced the islanders to rely on rain-fed agriculture and live without diversified income sources and access to necessary assets, exacerbating their food and income insecurity and reducing their adaptive capacity. As a Tappu resident commented, “We have a plenty of water flowing in the river nearby, but we don’t have water for irrigation.” The lack of economic opportunities pushed them to seek foreign labour employment in Malaysia and the Middle East, albeit a few islanders were able to meet the recruitment costs. The employment also became the highest-paying occupation on the islands. Some islanders utilised remittances sent home from the overseas to purchase land outside the island in addition to the land they previously occupied, hoping to reduce flood risks. It was because their vulnerability to flooding did not decrease despite owning land on the islands.

In other words, the river’s poor governance has a substantial impact on the islanders’ adaptive capacity. First, only a few islanders could afford the basic assets required to adapt to floods. Second, many of them lacked the capacity to mobilise their assets for better adaptation due to a lack of agency and competing concerns, such as managing day-to-day food needs, illustrating the lack of mobilisation capacity essential for enhancing adaptive capacity, as argued by Mortreux and Barnett (2017) and Barnes et al. (2020). Only a few islanders were able to buy property in safer locations using remittances, income from farming, and animal sales. Third, they lacked the ability to transmit adaptive capacity from elsewhere, contrary to what Elrick-Barr et al. (2022) suggested about capacity transfer between individuals and groups. The lack of transfer ability was because of an absence of social networks outside of their islands. This study supports prior findings by McEvoy et al. (2020) in the South Pacific regarding the weak planning and practice, resulting in haphazard decisions and/or inaction on critical and urgent issues, and Chau et al. (2014) and Gerlitz et al. (2017) on the weak presence of the local, national, and international government authorities in supporting people when needed. It also resonates with Gerlitz et al. (2017) and Giri et al. (2021) regarding the escalating vulnerability due to the unaffordability of diverse income options. However, the lack of diverse income options was mainly due to the authorities’ irresponsibility in not facilitating the islanders in any income-generating activities despite their reliance on the neighbouring villages for almost everything. Because of lack of livelihood options, they had to rely heavily on weather-dependent income, which further increased their vulnerability to floods, echoing studies by Gentle and Maraseni (2012) and Hallegatte et al. (2016). McEvoy et al. (2020) in the South Pacific and Ghimire et al. (2010) in Nepal found that access to land rights reduced people’s vulnerability; however, this did not happen with the Koshi River islanders. They remained vulnerable because they lived on the risky locations, which instead resonated with studies by Thomas et al. (2019) and Turner et al. (2003). Another factor contributing to the islanders’ increased vulnerability, notably among the Gobargadha residents, was a lack of critical flood information during the opening of the barrage gates, which is exactly what Brunn and Casse (2013) found in Central Vietnam and McEvoy et al. (2020) discovered in the South Pacific.

The findings of this study show that lack of good governance was one of the major causes of vulnerability. The main actors, the governments of Nepal and India, failed to act responsibly and accountably towards the river islanders. They either misused or failed to use their power effectively in making critical decisions and implementing them. Besides weak planning and absence of government and project authorities on the islands, poverty, location, house type, security situation, health and transportation facilities, access to food, income and land, and the islanders’ capacity to mobilise and transfer adaptive capacity, including historical aspects of the KRA determined vulnerability. In addition, climate change is happening. Although studying the impacts of climate change on the islands is beyond the scope of this study, it is evident that the basin has experienced both increasing flood frequency and extremely severe droughts in the past several decades that have had an impact on agriculture and water supply (Dahal et al., 2021; Paudel et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2019). Pradhan and Shrestha (2022) estimated over 10% increase in monsoon rainfall in the basin’s low-lying plain region between 2021 and 2076. The rainfall pattern is expected to increase future catastrophic events including floods, flash floods, soil erosion, and landslides. Such a situation will increase the islanders’ vulnerability to floods, resulting in disasters. The situation will become much worse unless the vulnerability contributing factors are addressed well. For this, good governance is required, which includes responsible and accountable decision-making processes and arrangements, as well as the effective and efficient use of power in critical and coordinated roles that address the needs of the local people.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was conducted only on the Nepalese side due to fieldwork logistics. The inclusion of riverine people from the Indian side would portray a different story. Second, the fieldwork was conducted during the period just before the monsoon started, which prevented me from experiencing and observing the islanders during flooding. Third, the use of local research assistants posed a challenge in collecting some sensitive information from the islanders, for example, income. However, data triangulation and correction during the data entry from the field notes helped overcome the hurdle. Fourth, the study did not investigate climate change variables and examine climate change impacts on the islands. Thus, future research on the production of vulnerabilities in transboundary river communities in the context of anthropogenic climate change is necessary. As riverine people living in the transboundary governance settings become vulnerable when governance mechanisms are not effective, future studies that examine the responsibility and accountability of key actors involved in the governance are needed.

6 CONCLUSION

This article has shown how the Koshi River governance has disproportionately shaped the two river communities’ vulnerability to flooding on the upstream and downstream islands of the Koshi barrage, and revealed how it will continue to shape their vulnerability in the future with increasing effects of climate change. The question of governance in relation to vulnerability assessments that was generally missing in the vulnerability assessment literature, particularly the climate vulnerability literature, has been addressed here. The findings suggest that the islanders’ vulnerability is produced locally and also shaped by national and international social, political, and economic contexts. Multi-scalar social, economic, political, historical, and ecological processes occurred in isolation and also concomitantly influenced escalating flood exposures, elevated levels of sensitivity, and shrank adaptive capacities to cope with the hazards. When there is lack of coordinated governance and the main players become irresponsible and unaccountable to the people, planning and practice become weak, increasing vulnerability to hazards to the extent that recovery is difficult.Authorities’ inefficiencies and ineffectiveness in making proper decisions and managing people and floodplains influence people to live on floodplains. Unless major players make responsible decisions, even having access to a critical resource, such as land in the case of the islanders, is insufficient to reduce vulnerability. Furthermore, people are left defenceless because of the lack of strong government agencies and institutions in communities, timely access to critical information on hazards, diverse income opportunities, and their pursuit of weather-dependent subsistence occupations. People’s vulnerability to hazards escalates when major players overlook them and fail to act on critical matters in a governance process.

The article has also shown that vulnerability is a relational concept, demonstrating that governance failure leads to severe climate vulnerability. Just asking “how” people become exposed is insufficient. To understand vulnerability holistically, asking “why” is crucial because it brings out underlying or hidden reasons or causes of vulnerability. For such ends, exploring people’s stories becomes crucial for understanding who and how decisions are made and then disseminated to people. Understanding the political economy of hazard production is, therefore, crucial for understanding vulnerability. Therefore, the study of historical, social, economic, political, geographical, and ecological processes is critical in any social vulnerability analysis.

Last, as climate change is real and happening, highly uncertain precipitation patterns and water flows in rivers are becoming more frequent. This outcome, in turn, is directly escalating the vulnerability of riverine people and indirectly affecting other people who depend on river waters, especially across political borders. It is vital to reframe transboundary river governance, stressing powerful players’ responsibility and accountability towards the people being governed. More research is needed on the construction of vulnerabilities, especially in transboundary river settings that are highly prone to anthropogenic climate change impacts. The historical and socio-ecological aspects of vulnerability and people’s perceptions and stories need to be integrated into the climate vulnerability literature. A better understanding of relationships between water governance and vulnerability is necessary to enhance people’s lives and livelihoods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Professor Phil McManus and Dr Robert Fisher, my research supervisors, for their continuous encouragement and constructive feedback during this article’s development. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All participants gave their consent before they participated in the interviews and surveys. The study was done in accordance with the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), the University of Sydney.

ENDNOTES

- 1 The region encompasses eight nations, from Myanmar in the east to Afghanistan in the west, with China, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Bhutan in between (Satyal et al., 2017).

- 2 Since the fieldwork was done a new constitution has been adopted in Nepal and the former VDCs have been abolished and the islands are now in new administrative units. In this article, the names of the administrative units applying at the time of fieldwork are used. Currently, Prakashpur and Gobargadha VDCs have been renamed as Barahkshetra Municipality-09, Sunsari, and Hanumannagar Kankalini Municipality-13, Saptari, respectively.

- 3 The contract was locally known as adhiya. Adhiya is an informal oral contract between the landowner and the tiller, under which the tiller promises to provide a certain percentage, usually half, of agricultural produce to the owner.

- 4 Then the lowest administrative unit, later renamed VDCs.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable - no new data generated