Dynamic changes of serum cytokines and their prognostic values in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by thermal ablation

Abstract

Background

Thermal ablation is effective for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It can induce a host immune response through dynamic changes in serum cytokines. It is unknown whether this host immune response correlates with tumour recurrence. This prospective study aims to investigate the dynamic changes of serum cytokines after thermal ablation of HCC and its clinical significance.

Methods

Sixty patients with HCC treated by thermal ablation were recruited. The dynamic changes of 39 serum cytokines were measured. The primary outcome was 2-year disease-free survival. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the prognostic factors for disease-free survival.

Results

Six cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, epidermal growth factor (EGF), eotaxin, transforming growth factor (TGF)-α] demonstrated significant dynamic changes after thermal ablation. The overall tumour recurrence rate was positively correlated with the dynamic changes in serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels. The 2-year disease-free survival was 49.7%. Serum bilirubin (≥25 μmol/L) and dynamic change of serum IL-10 (≥22 IU/mL) levels were the significant independent prognostic factors for disease-free survival.

Conclusion

There are significant dynamic changes in serum cytokines after thermal ablation. High serum bilirubin and upregulation of serum IL-10 levels are independent poor prognostic factors for tumour recurrence after thermal ablation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is the sixth most common malignancy in the world. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths and had a global incidence of more than 740 000 new cases in 2019.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 75% to 85% of primary liver cancer. Hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and orthotopic liver transplantation are the curative treatment options for early-stage HCC.2 Nonetheless, hepatectomy is only indicated in patients with early-stage HCC and preserved liver function, whereas application of liver transplantation is limited globally because of the organ shortage. Thermal ablation by either RFA or microwave coagulation (MWA) is therefore the most effective treatment in patients with HCC and borderline liver function due to cirrhotic liver, especially in the Asia-Pacific region where hepatitis B infection is prevalent.

Thermal ablation kills tumours via direct thermal denaturation and coagulation of tumour proteins.3 The retention of devitalised and damaged tumour cells within the body stimulates complex and robust inflammatory responses. It has been reported that thermal ablation creates a tumour antigen source for the generation of antitumor immunity and enhances host immune responses.4 In the process of complete ablation by thermal energy, the exposed tumour cells in the sublethal ablation zone may be affected positively or negatively by the concomitant inflammatory responses including increased levels of cytokines and growth factors. Inflammation following ablation may have negative effects via the production of growth factors and cytokines by macrophages and lymphocytes, which could stimulate tumour cell growth within the sublethal zone.5 Thus, the role of systemic inflammatory reaction by the release of cytokines on the subsequent tumour recurrence after thermal ablation is yet to be defined.

Human and animal studies using immunohistochemical staining of tissues, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of tissue lysates, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of plasma have shown a significant increase in specific inflammatory and immunomodulatory mediators after thermal ablation.6-8 Although pre-clinical studies on inflammatory responses of thermal ablation for liver tumours are substantial, the clinical correlation of this microenvironmental reaction is limited in the literature. A study on the results of 209 patients receiving RFA as the sole treatment for HCC showed that the overall tumour recurrence rate was up to 80% with a median follow-up of 26 months.9 Hence, the identification of high-risk patients who might develop early recurrence using surrogate biomarkers (eg, cytokines) carries an important clinical implication on the use of adjuvant treatment (eg, immune checkpoint inhibitor). It is hypothesised that thermal ablation for HCC may induce an inflammatory immune response, resulting in changes in cytokine levels. This microenvironmental reaction might positively or negatively regulate the residual tumour cells, leading to subsequent tumour recurrences. The present single-centre prospective study aims to analyse the dynamic changes in serum cytokines levels in patients with HCC treated by thermal ablation. The result is used to correlate the clinical outcome of patients (ie, early tumour recurrence within 2 years). Combined with other clinicopathological parameters, a prognostic model is derived to identify high-risk patients for early tumour recurrence after thermal ablation for HCC.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and patient selection

This is a single-centre prospective study at a high-volume tertiary referral liver centre in Hong Kong (Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong). The Institutional Review Broad of The Chinese University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority New Territories East Cluster and Hospital Authority West Kowloon Cluster reviewed and approved this study. From June 2020 to December 2021, patients with HCC receiving thermal ablation as the first treatment were recruited. The inclusion criteria were (1) HCC of maximal diameter ≤5 cm, (2) multiple tumour nodules ≤5, (3) liver (serum total bilirubin level < 50 μmol/L and serum albumin >30 g/L), (4) renal function (serum creatinine level < 120 μmol/L), and (5) Child–Pugh class A or B.10 The exclusion criteria were (1) evidence of extrahepatic metastasis, (2) patients receiving combined hepatectomy and other local ablative therapy, (3) patients with decompensated liver function that precludes local ablative treatment, (4) patients with previous treatment for HCC (transarterial chemoembolisation, RFA, high-intensity focus ultrasound or systemic chemotherapy), (5) patients with inadequate serum sample for cytokine analysis, and (6) patients who failed to sign the consent form.

2.2 Pre-treatment investigation and assessments

The diagnosis of HCC was made in accordance with the diagnostic criteria for HCC used by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.11 HCC was diagnosed when the radiologic imaging techniques (spiral contrasted computed tomography [CT] scan or contrasted magnetic resonance imaging) showed typical features of HCC (contrast enhancement in the arterial phase and rapid wash-out of contrast in the venous or delayed phase) and/or the serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level was elevated (>200 ng/mL). All patients had the following pre-treatment investigations and assessments: (1) blood tests: complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, coagulation profile, serum AFP level, and hepatitis B and C serology; (2) radiological imaging study: CT scan of the thorax and abdomen with contrast to exclude lung metastases or intraabdominal metastases.

2.3 Treatment Procedures

Thermal ablation by either RFA or MWA was performed under standard protocols.9, 12 The electrode is effective in producing complete tumour necrosis with ablation of a margin of nontumorous tissue of 1 cm. The procedure will be performed percutaneously by an experienced interventional radiologist under local anaesthesia with intravenous sedation if a tumour is accessible by the percutaneous route. For tumours located at the liver dome or if there was a risk of thermal injury to adjacent structures like the diaphragm and bowel, thermal ablation will be performed through a laparoscopic or open approach. Subcapsular tumours are approached by either a laparoscopic or an open approach.13 A spiral contrasted CT scan will be performed 4–6 weeks after the procedure to assess the completeness of ablation. In case of incomplete ablation, repeat ablation will be attempted to achieve complete tumour ablation.

2.4 Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure is early intrahepatic tumour recurrence within 2 years after treatment (2-year disease-free survival [DFS]). The secondary outcome measures are treatment-related complications, mortality, tumour recurrence pattern (intrahepatic recurrence and extrahepatic metastasis), and overall survival.

The following procedure-related parameters were documented. These include the type of thermal ablation (RFA or MWA), ablation time, intraoperative blood loss, blood transfusion requirement, and the treatment approach (percutaneous, laparoscopic, or open). Short-term outcomes were documented. These included (1) post-operative morbidities according to the Clavien–Dindo classification14 (documented morbidities were wound complication, pulmonary complication, hemoperitoneum, biliary complications, liver failure, and renal failure); (2) hospital mortality (any death within the same admission for surgery); and (3) intensive care unit stay and total hospital stay.

No adjuvant treatment will be given after the procedure. All recruited patients will be followed up regularly. Liver function (complete blood picture, liver biochemistry, and coagulation profile) and serum AFP level were taken every 3 months during follow-up. Spiral contrast-enhanced CT scan of the thorax and abdomen will be performed every 6 months after treatment, respectively, to look for tumour recurrence. Long-term outcomes including tumour recurrence (intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic recurrence) and overall survival and DFS were documented.

2.5 Analysis of cytokines level

Serum samples were collected from each recruited patient for the analysis of cytokines levels before the procedure and 1 week after the procedure. Using a commercially available kit (MILLIPLEX MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel-Immunology Multiplex Assay), the levels of 39 cytokines (epidermal growth factor [EGF], fibroblast growth factor 2 [FGF-2], EOTAXIN, transforming growth factor [TGF]-α, granulocyte colony–stimulating factor [G-CSF], fibromyalgia syndrome-related Tyrosine - 3 ligant [FLT-3 L], granulocyte–macrophage colony–stimulating factor [GM-CSF], Fractalkine, interferon [IFN]α2, IFNg, growth regulatory oncogene, IFN-α2, IFN-γ, interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 [p40], IL-12 [p70], IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, interferon-gamma-induced protein 10 [IP-10], monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1], MCP-3, macrophage inflammatory protein [MIP]-1α, MIP-1β, soluble cluster of differentiation 40 ligand, tumour necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], TNF-β, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF]) were analysed. This is an overnight incubation assay.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All data will be prospectively collected by a research assistant and computerised in a database. Statistical analysis will be performed by the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, where appropriate, to compare discrete variables and the Mann–Whitney U test to compare continuous variables. Cumulative survival will be computed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazards regression model were performed to identify significant prognostic factors affecting the DFS rate. Potential prognostic factors included patient demographics (age, sex, and comorbidities), liver function (serum bilirubin, serum albumin, and Child–Pugh grading), operative parameters (blood transfusion and surgical approaches), pathological features (size of largest tumour and tumour number), and the dynamic changes of selected serum cytokines. The median value was chosen to be the cut-off point of continuous variables in the Cox proportional hazards regression model.

3 RESULTS

From June 2020 to December 2021, 60 patients with HCC who underwent thermal ablation by either RFA or MWA were recruited. The patient demographic and tumour characteristics are described in Table 1. The median age was 69 years. There were more male patients than female patients (83% vs 17%). The majority of patients were hepatitis B virus carriers (70%) and had Child's A liver function (97%). The median Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score was low (score = 8). Tumour size ranged from 0.8 to 5 cm. The majority of patients had a single tumour (83%). Twenty-nine patients (49%) and 31 patients (51%) underwent RFA and MWA, respectively. The ablation treatment was performed through percutaneous (65%), laparoscopic (13%), and open (22%) approaches.

| Characteristics | Patient group (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Age | 69 (49–85) |

| Sex (male: female) | 50 (83): 10 (17) |

| Hepatitis B viral infection | 42 (70) |

| Hepatitis C viral infection | 7 (12) |

| Concomitant medical illnesses | 54 (90) |

| Child–Pugh classification | |

| Class A: Class B | 58 (97): 2 (3) |

| Serum bilirubin (μmol/L) | 11 (3–42) |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 36 (19–44) |

| Serum alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 26 (10–129) |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 149 (58–370) |

| International normalised ratio | 1.05 (0.89–1.74) |

| Model for End-Stage Liver Disease | 8 (6–20) |

| Serum alpha-fetoprotein level (ng/mL) | 6 (1–1407) |

| Size of tumour (cm) | 2 (0.8–5) |

| No. of tumour nodules (single: multiple) | 50 (83): 10 (17) |

| Distribution of tumours (unilobar: bilobar) | 57 (95): 3 (5) |

| Ablation energy (radiofrequency ablation: microwave coagulation) | 29 (49): 31 (51) |

| Approaches of local ablation | |

| Percutaneous | 39 (65) |

| Laparoscopic | 8 (13) |

| Open | 13 (22) |

- Note: Continuous variables are expressed as median (range). Categorical variables are expressed as n (%).

The short-term outcome is described in Table 2. Complete ablation was achieved in 58 patients (96.6%). The procedure-related blood loss during open or laparoscopic ablation was minimal (median 30 mL) and none of the patients required a blood transfusion. The post-operative complication rate was 11.7%. There was one patient who developed severe procedure-related complications. The patient had symptomatic ascites, which required image-guided abdominal drainage. There was no hospital mortality. The median hospital stay was 3 days.

| Outcome | Patient group (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Complete ablation | 58 (96.6) |

| Ablation duration (min) | 27 (12–53) |

| Operative blood loss (mL)a | 30 (10–123) |

| Blood transfusion (units) | 0 (0) |

| Hospital mortality | 0 (0) |

| Post-operative complications | 7 (11.7) |

| Liver abscess | 0 (0) |

| Bile duct injury | 0 (0) |

| Liver failure | 0 (0) |

| Symptomatic ascites | 0 (0) |

| Chest infection (with respiratory failure) | 1 (1.7) |

| Symptomatic pleural effusion | 1 (1.7) |

| Renal failure | 0 (0) |

| Wound complications | 5 (8.3) |

| Severe complications (Clavien–Dindo Classification Grade IIIa or above) | 1 (1.7) |

| Hospital stay (days) | 3 (1–18) |

- Note: Continuous variables are expressed as median (range). Categorical variables are expressed as n (%).

- a Only apply to laparoscopic and open approaches.

Of the 39 cytokines, 6 demonstrated significant dynamic changes in serum level before and 1 week after the procedure. They were IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, EGF, eotaxin, and TGF-α (Table 3) Following the ablation process, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10 and EGF were upregulated, whereas eotaxin and TGF-α were downregulated.

| Cytokines | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Differences | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin-1 | 12.6 (2.3–538.4) | 22.1 (4.9–348.5) | 14.6 (6.5–146.2) | <.001 |

| Interleukin-6 | 1.4 (1.1–59.4) | 13.6 (6.3–91) | 11.6 (5.2–196.2) | <.001 |

| Interleukin-10 | 13.4 (2.3–106) | 67 (47–115) | 22 (2.7–96.2) | <.001 |

| Epidermal growth factor | 24 (13–538.4) | 129.8 (26–861.5) | 126 (22–423.3) | <.001 |

| Eotaxin | 149.7 (117.4–436.3) | 102.4 (100.6–288.5) | −127 (−338.7 to −83.1) | <.001 |

| Transforming growth factor-α | 280 (198–880) | 108 (21–464) | −182 (−383 to −81) | .035 |

- Note: All cytokines are measured in IU/mL and are expressed as median (range).

With a median follow-up period of 18 months, 20 patients (33.3%) developed tumour recurrence (local recurrence n = 12, intrahepatic recurrence n = 19, and extrahepatic recurrence n = 1). All patients with local recurrence had tumour recurrence over the previous ablation site. The recurrence pattern is described in Table 4. Seven patients (11.7%) received hepatic resection, and 10 patients (16.7%) had transarterial chemoembolisation as salvage treatment for recurrent tumours. Among seven cytokines with significant dynamic changes following ablation, upregulation of IL-6 and IL-10 levels was positively correlated with the overall tumour recurrence rate (Table 5).

| Ablation group (n = 60), n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Tumour recurrence pattern | |

| No recurrence | 40 (66.7) |

| Local recurrence | 12 (20.0) |

| Intrahepatic recurrence | 19 (31.7) |

| Extrahepatic recurrence | 1 (1.7) |

| Treatment modality for recurrence | |

| Hepatic resection | 7 (11.7) |

| Local ablation | 1 (1.7) |

| Transarterial chemoembolisation | 10 (16.7) |

| Resection for peritoneal metastasis | 1 (1.7) |

| Supportive care | 1 (1.7) |

| Cytokines | Tumour recurrence (n = 20) | No recurrence (n = 40) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin-1 | 15.6 (76 to 146.2) | 16.4 (65 to 111.5) | .724 |

| Interleukin-6 | 28.3 (11.7 to 196.2) | 11.6 (5.2 to 103.2) | .021 |

| Interleukin-10 | 65 (31.1 to 96.2) | 22 (2.7 to 53) | .012 |

| Epidermal growth factor | 131 (22 to 312.4) | 126 (52 to 423.3) | .762 |

| Eotaxin | −118 (−338.7 to −102.4) | −127 (−287.1 to −83.1) | .558 |

| Transforming growth factor-α | −182 (−383 to −102) | −113 (−263 to −81) | .076 |

- Note: All cytokines are measured in IU/mL and are expressed as median (range).

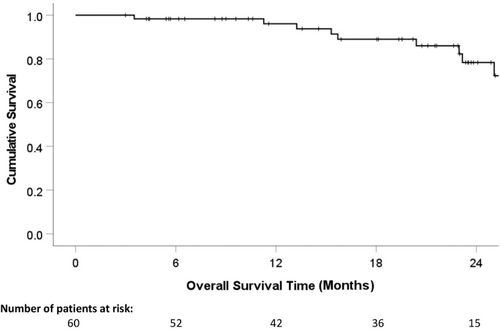

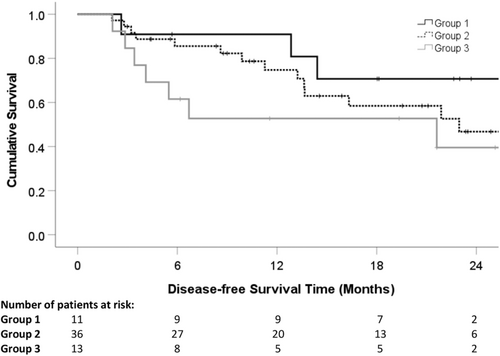

The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were 96.1% and 74.8%, respectively (Figure 1). The 1- and 2-year DFS were 73.2% and 49.7%, respectively (Figure 2). Table 6 presents the results from the univariate and multivariate analyses of potential prognostic factors for DFS. The pre-treatment high serum bilirubin level (≥25 μmol/L) (hazard ratio 0.965, 95% confidence interval 0.349–0.997, P = .032) and the upregulation of post-treatment serum IL-10 (≥22 IU/mL) (hazard ratio 0.723, 95% confidence interval 0.383–0.867, P = .008) were the significant poor independent prognostic factors influencing DFS (Table 6). Patients were then stratified into three groups (Group 1: no risk factor, n = 11; Group 2: one risk factor, n = 36; Group 3: two risk factors, n = 13). The 1- and 2-year DFS rates of Groups 1, 2, and 3 were 90.9% and 70.7%, 74.8% and 46.8%, and 52.7% and 39.6%, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in DFS between Groups 1 and 3 (P = .003; Figure 3).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

| Age (<60 vs ≥60 years) | 1.029 (0.351–3.016) | .958 | ||

| Sex (male) | 0.872 (0.539–1.371) | .736 | ||

| Presence of comorbidities | 0.897 (0.769–1.064) | .298 | ||

| Serum albumin (<30 vs ≥30 g/dL) | 1.005 (0.909–1.110) | .928 | ||

| Serum bilirubin (≥25 vs <25 μmol/L) | 0.725 (0.324–0.977) | .018 | 0.965 (0.349–0.997) | .032 |

| Child–Pugh Classification | ||||

| Class A vs Class B | 0.715 (0.201–0.976) | .476 | ||

| ICG-15 (≤15 vs >15%) | 0.828 (0.511–1.644) | .665 | ||

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 0.998 (0.995–1.002) | .437 | ||

| Blood transfusion (yes) | 1.270 (0.619–3.876) | .496 | ||

| Surgical approach | ||||

| Open vs MIS (Lap/Percut) | 0.811 (0.697–3.089) | .788 | ||

| Post-operative complications | 1.893 (0.026–2.483) | .037 | 2.022 (0.872–3.748) | .267 |

| Size of the largest tumour (<3 vs ≥3 cm) | 0.823 (0.203–1.313) | .002 | 1.883 (0.778–1.023) | .723 |

| Number of tumours | ||||

| Solitary vs multiple | 0.545 (0.345–1.439) | .450 | ||

| Changes of interleukin-6 (≥11.6 vs <11.6 IU/mL) | 0.635 (0.217–0.993) | .002 | 0.712 (0.366–2.912) | .763 |

| Changes of interleukin-10 (≥22 vs <22 IU/mL) | 0.722 (0.536–0.991) | .046 | 0.723 (0.383–0.867) | .008 |

- Abbreviations: ICG: indocyanine green; MIS: minimally invasive surgery; Lap: laparoscopic; Percut: percutaneous.

4 DISCUSSION

Based on a prospective analysis of 60 patients with HCC treated by thermal ablation, this study provides clinical evidence that thermal ablation of liver tumours can induce significant dynamic changes in serum cytokines, which carry a prognostic value in the development of tumour recurrence after ablation. Among seven cytokines demonstrating upregulation or downregulation after ablation, upregulation of IL-6 and IL-10 was associated with tumour recurrence of HCC. More importantly, in the multivariate analysis, a pre-treatment high serum bilirubin level (≥25 μmol/L) and post-treatment upregulation of serum IL-10 (≥22 IU/mL) were significant, independent poor prognostic factors influencing DFS. Using this model, patients with two risk factors (high pre-treatment serum bilirubin and high post-treatment serum IL-10) had significantly worse DFS than those without risk factors (2-year DFS rates: 39.6% vs 70.7%).

Thermal ablation is an effective treatment for malignant liver tumours.2, 15 A previous randomised trial has demonstrated a comparable overall survival and DFS between hepatic resection and thermal ablation for early-stage HCC.16 The reported complete ablation rate was over 90% and the 5-year overall survival rate was over 40%. Nevertheless, the reported tumour recurrence rate was over 80% in 5 years.9

Different clinical factors have been evaluated to account for tumour recurrence, including tumour type (HCC and colorectal liver metastasis), tumour size (≥3 cm), and ablation margin (<0.5 cm).17

Apart from clinical parameters, systemic immune markers have been studied for their role in the thermal ablation of liver tumours and subsequent tumour recurrence. It is generally believed that thermal ablation can induce systemic immune response by the release of cytokines and inflammatory processes.18, 19 Activated platelets release IL-1, TNF-α, and TGF-β, which increase vascular permeability and promote chemotaxis. Neutrophils are attracted to the ablation site and perform debris scavenging by releasing free radicals via oxidative burst mechanisms aimed at destroying inciting agents. Macrophage migration ensues, transitioning to the proliferative stage, during which macrophages secrete growth factors, including TNF-α, VEGF, and basic FGF.20 The level of proliferative activity of macrophages and lymphocytes is mediated by IL-6 positively and IL-10 negatively.21, 22 Erinjeri et al.23 reported that the ablation type and primary diagnosis predicted the change of serum IL-6 levels and patient age predicted the change of serum IL-10 levels after thermal ablation of tumours. IL-6 may act as a surrogate for immunogenic cell death and the combination of immunogenic death–inducing procedures with immune checkpoint inhibitors may be beneficial to prolong patient survival after RFA.24 At the cellular level, RFA has proven to enhance tumour-associated antigen-specific T-cell response and this may contribute to the long-term survival of patients.25 Zerbini et al.26 found that thermal ablation induced significant upregulation of circulating tumour-specific T cells and T-cell responses to recall antigens. Phenotypic analysis of circulating T and natural killer cells showed increased activation and cytotoxic surface marker expression.

Our findings indicate that the seven types of cytokines were either upregulated (IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, and EGF) or downregulated (eotaxin and TGF-α) regulated after the ablation process. Similar findings were also reported by other studies. Guo et al.27 revealed that there was a significant positive correlation between IL-6 level and white blood cell count after thermal ablation, suggesting a systemic inflammatory reaction. IL-6 is a biomarker reflecting the degree of hepatic trauma and subsequent inflammation. Another cytokine, IL-10, is an anti-inflammatory T helper 2 (Th2) cytokine that promotes immunosuppression, whereas TGF-α is a T helper 1 (Th1) cytokine that stimulates immune responses. The simultaneous upregulation of IL-10 and downregulation of TGF-α indicates that the Th1/Th2 balance could be disturbed, reshaped, and polarised to either the Th1 or the Th2 status. This could subsequently affect tumour-related immune responses.

The relationship between the dynamic changes in the immune-related microenvironment and the subsequent tumour recurrence after thermal ablation remains unclear. To address this question, the present study found that the upregulation of post-treatment serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels was associated with overall HCC tumour recurrence. A study by Cho et al.28 revealed that a low pre-treatment IL-6 level, in addition to low platelet and bilirubin levels, was an independent prognostic factor for DFS of patients with HCC undergoing hepatic resection or thermal ablation. Another study showed that a high pre-treatment IL-10 level was associated with tumour recurrence during the 1-year follow-up.27 A systemic review and meta-analysis showed that IL-10 played an important role in tumour microenvironment and HCC carcinogenesis.29 One limitation of these cytokine studies is that only a specific time point for the measurement of cytokine was chosen. The present study is therefore unique in demonstrating the association between dynamic changes of IL-6 and IL-10 and HCC tumour recurrence after ablation. From the present study, cytokine IL-6 and IL-10 levels can be checked preoperatively and within 1 week post-operatively to evaluate their dynamic changes following thermal ablation. This may provide some hint on subsequent tumour recurrence.

Another highlight of the present study is that a prognostic model on HCC recurrence after ablation was developed by combining both clinical parameters and dynamic cytokine changes. Such information is limited in the literature. By multivariate analysis, two important risk factors for tumour recurrence were found, namely, high serum bilirubin (≥ 25 μmol/L) and high upregulation of serum IL-10 (≥ 22 IU/mL). Patients with these risk factors are prone to develop tumour recurrence after thermal ablation (2-year DFS < 40%). This study is of clinical importance in establishing the potential role of immune response as surrogate biomarkers to predict HCC recurrence after thermal ablation. It establishes the model to identify high-risk patients for potential adjuvant treatment such as immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with HCC treated by thermal ablation. Potentially, cytokine-based immunotherapy involving IL-10 may be beneficial in this high-risk group.30

The present study has the following limitations. First, the number of patients recruited is relatively small. It would be desirable to carry out a large-scale study to alleviate the potential statistical error. Second, this is a single-arm study. Ideally, there should be a control group involving patients with HCC treated by other types of therapy, for example, hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolisation. Third, the thermal ablation approaches might affect the systemic immune response (minimally invasive vs open). Expectedly, the systemic immune response following an open approach may be more intense than that following a minimally invasive approach (percutaneous or laparoscopic). Moreover, the use of MWA or RFA may result in different immune responses, given that the temperature of MWA is higher than that of RFA. A subgroup analysis focusing on each of these approaches should be done if there are sufficient patient numbers. Fourth, the risk-factor model only provides some clues on tumour recurrence. It lacks the role of monitoring tumour recurrence, unlike AFP.

In conclusion, there are significant dynamic changes in serum cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, EGF, eotaxin and TGF-α) after thermal ablation of HCC. High pre-treatment serum bilirubin and upregulation of serum IL-10 levels after treatment are independent poor prognostic factors for tumour recurrence after thermal ablation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully thank Mr. Philip Ip (Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong) for his excellent help with data collection and analysis.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study is supported by a research grant from the Hong Kong Society of Gastroenterology.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.