Transanal total mesorectal excision: Understanding indications, managing complications, and effective prevention methods

Abstract

Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) has emerged as a surgical method for treating rectal malignancies in the middle and lower third of the rectum over the past 15 years. This approach was adopted because of the challenges encountered in secure total mesorectal excision (TME). Patient selection criteria and the rationale for TaTME have evolved, leading to improved oncological outcomes and patient quality of life. The procedure includes inserting a unique platform through the anus, forming a purse-string closure, and endoscopically sealing the lower rectum. The mesorectum is then removed laparoscopically following a ‘down-to-up’ approach, finalised with a transabdominal laparoscopic phase and anastomosis. Pelvic anatomy complexity poses challenges, including potential injuries to the urinary tract, surgical site leakage, sinus damage, sagittal vein harm, nerve injury, carbon dioxide embolism, bowel function disturbance, sphincter mechanism issues, and rectal abscess formation. Proficient anatomy knowledge, precise surgical techniques, and advanced technologies contribute to their prevention. In conclusion, TaTME offers a promising approach to rectal surgery with satisfactory oncological outcomes. However, vigilance is required to eliminate potential complications.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) has emerged as a notable surgical approach for the management of rectal malignancies in the middle and lower thirds of the rectum. Initially developed to face the challenges encountered in achieving secure total mesorectal excision (TME), TaTME has undergone significant refinement and acknowledgement within the surgical community. This article aims to explore the indications, complications, and strategies for their prevention. We aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of this evolving surgical technique and its impact on patient outcomes.

Malignant rectal cells can metastasise not only within the mucosa and muscular tissue, but also in the mesorectum, the peritoneal lining of the upper rectum. Two distinct studies have shown that no cancerous growths were detected in implants located more than 4 cm away from the primary tumours of T3 and T4 stage, or more than 1 cm away from the primary tumours of T1 and T2 stage.1, 2 Thus, it has been suggested to remove 5 cm of the mesorectum beyond the tumour during TME.3

For malignancies located in the middle and lower third of the rectum, complete removal of the midrectum down to the pelvic floor is critical, given that the rectum spans 12 to 15 cm.4 Conversely, for malignancies in the upper rectum, it is sufficient to remove the mesorectum at a length of 5 cm below the primary tumour.

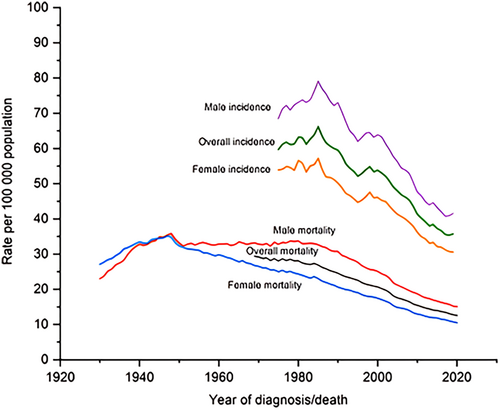

Complete removal of the mesorectum has been associated with a decrease in local recurrence rates (4%–7%) and improved survival, establishing it as the preferred treatment for rectal cancer.5 By contrast, surgeries performed without TME have led to local recurrence rates ranging from 14% to 45%, depending on the use of adjuvant therapy.6

While the conventional approach to TME involved open transabdominal surgery, laparoscopic and robotic techniques are increasingly preferred owing to their advantages of shorter hospital stays, reduced post-operative pain, improved cosmetic outcomes, faster recovery of intestinal function, decreased blood loss, and enhanced surgical visibility.

Recent research, including the worldwide multicentre COLOUR II study, has demonstrated the non-inferiority of laparoscopic complete mesorectal excision compared with open surgery, in terms of oncological outcomes.7 However, certain factors such as a narrow pelvis, male gender, obesity, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, or the location of the tumour in the lower third and anterior wall of the rectum can complicate surgery and lead to poorer outcomes. TaTME, introduced by Sylla et al,8 is specifically addressed to such challenging locations and aims to achieve a complete and uncomplicated TME preparation.

Furthermore, the multicentre COLOUR III study showed that TaTME resulted in superior attainment of negative circumferential resection margin compared with the laparoscopic approach, regarding malignancies of the middle and lower third of the rectum.9

2 PATIENT SELECTION—INDICATIONS

The indications of TaTME have undergone three revisions between 2014 and 2019. Initially, indications included male patients with a body mass index over 30 kg/m2, tumour size larger than 4 cm, and tumours located less than 12 cm from the anal verge. Contraindications included obstructive tumours, emergency surgery, and T4-stage tumours.10

In 2017, the St.Gallen Colorectal Consensus Expert Group presented new guidelines, stating that the technique could be used for both non-cancerous and cancerous conditions.11 The selection criteria no longer included gender, but focused on visceral obesity and previous pelvic procedures. Larger tumours of the middle and lower third of the rectum were also an indication.

Finally, in 2019, a consortium of 56 specialised surgeons set the current TaTME selection criteria.12 These included previous prostatectomy, a history of complicated pelvic surgeries, and preoperative pelvic radiation therapy. Regarding tumour characteristics, the technique is suggested for those expected to present technical difficulties during pelvic preparation, those located in the middle and lower third of the rectum requiring total mesorectal resection, and tumours staged as cT4 and Rullier type 3 (clamp filtered). The inability to reach the distal margin of transabdominal resection and previous full-thickness local excision lesions are additional indications.

TaTME may also be applied to benign conditions requiring proctectomy, such as those with technical difficulties in pelvic preparations; cases of sexually transmitted infections; inflammatory bowel disease; or familial adenomatous polyposis with ileoanal anastomosis, need for revision of ileoanal pouch, or anastomosis (Table 1).

| Second International taTME Conference 2014 | St.Gallen Colorectal Consensus Expert Group, 2018 | Dynamic Guidance 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Male gender, narrow +/− deep pelvis, visceral obesity +/−, body mass index > 30 kg/m2, and prostatic hypertrophy | Both genders; narrow pelvis; visceral obesity with a fatty mesorectum; and previous pelvic surgery, especially prostatectomy and mesh rectopexy | Previous prostatectomy, pelvic radiation, and complex pelvic surgerya |

| Tumour characteristics | Rectal cancer <12 cm from the anal verge, tumour diameter >4 cm, neoadjuvant therapy distorting tissue planes, impalpable, and low primary tumours | Bulky, mid/distal tumours, best for lower tumours needling total mesorectal excision, although partial mesorectal excision for higher tumours can be performed | Any malignant rectal resection where there is anticipated technical difficulty in pelvic dissection, only when total mesolectal excision is indicated, when a clear distal margin cannot be guaranteed by a pure abdominal approach, cT4 and Rullier type 3 juxtasphincteric rectal cancers can be considered for a transanal approacha, and following previous full-thickness local excision |

| Benign conditions | Inflammatory bowel disease requiring proctectomy, rectal strictures, complex fistulae, faecal incontinence, familial adenomatous polyposis, radiation proctitis, and removal of the orphaned rectum following colectomy | Inflammatory bowel disease requiring proctectomy or proctocolectomy, rectovaginal fistulae, pouch advancement procedures, and removal of a neorectum in cases of chronic anastomotic sinus/leak | Benign rectal resections where technical difficulty in pelvic dissection is anticipated, cases of inflammatory bowel disease requiring proctectomy, inflammatory bowel disease and familial adenomatous polyposis requiring an ileoanal pouch procedure with anticipated challenges in determining the level of distal transection, as well as revisions of an ileoanal poucha or refractory anastomosis–related sepsisa |

| Contraindications | Obstructing rectal tumours, emergency presentation, and T4 tumours | Not stated | Not stated |

- a Procedure recommended to take place in an expert centre for these cases.

As noted, while the indications and criteria for TaTME are outlined, contraindications are not mentioned.12 Furthermore, these criteria are often altered by the surgeon's preference and experience, as well as the available resources and capabilities of each medical centre.12

3 COMPLICATIONS AND PREVENTION METHODS

TaTME offers the surgeon the benefit of accessing the distal portion of the rectum; however, the rectum and mesorectum are located near several crucial anatomical structures. Deviating from the precise surgical plan during preparation can result in severe damage, leading to various complications, such as (1) urinary system injuries, (2) leakage of anastomosis, (3) vaginal and sacral venous plexus injuries, (4) damage to autonomic nerves, (5) carbon dioxide (CO2) embolism, (6) disorders of intestinal function and sphincter mechanism, and (7) rectal abscesses.

In a series of 1594 TaTME cases, Penna et al13 reported an incidence of 1.8% of visceral injuries during the perianal phase.

3.1 Urinary system injuries

A recent multicentre study conducted in 2021 documented 34 cases of urethral injuries, 3 cases of bladder injuries, and 2 cases of ureteral injuries associated with the TaTME procedure. Over the 28-month follow-up period, 26% of patients with urethral damage experienced enduring sequelae, with 18% reporting dysuric symptoms and 9% necessitating permanent cystostomy.13

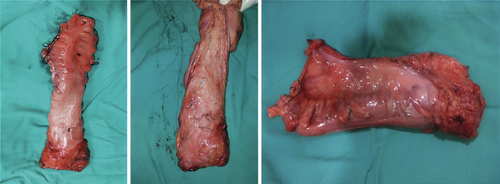

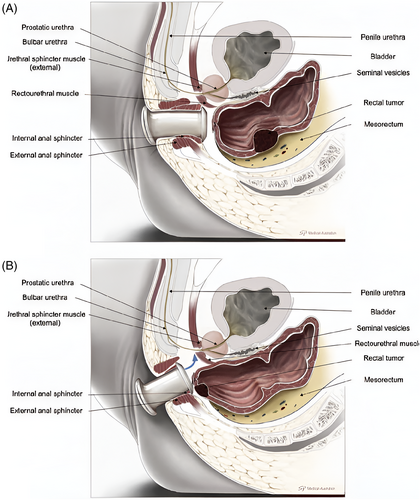

Urethral injury during TaTME usually results from non-meticulous anterior wall preparation, emphasising the critical importance of accurately identifying and distinguishing the surgical plane from the bottom upward. The risk of iatrogenic urethral damage augments significantly when preparing the pre-prostatic membrane urethra at extremely low rectal volumes (Figure 1), given its susceptibility to injury. Factors such as anterior wall tumours, hypertrophic prostate, prior prostatectomy, and neoadjuvant radiation therapy can further complicate surgical preparations.13

Prevention

- Detailed anatomical understanding: Prioritise detailed comprehension of the anatomical structures of the region, especially the rectourethral muscle's reduced thickness between the 11 o'clock and 1 o'clock positions during anterior preparation. Emphasise lateral preparations initially before centre-focused attention.

- Prostate palpation: Conduct a thorough digital rectal examination and palpation of the prostate to enhance surgical precision. In addition, precise identification of the symmetrical form and pale appearance of the lower lobe of the prostate is indispensable. Ultimately, discern the cylindrical form of the prostatic urethra.

- Meticulous identification of Walsh's neurovascular bundles is critical.14 Commence the preparation by identifying the lateral aspect before progressing sequentially to the centre.

- Indocyanine green (ICG) application: Utilise ICG administered through the urethra to augment urethral detection. ICG/NIR fluorescence techniques, such as the IRIS Urethral Kit (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) and the laparoscopic PINPOINT system (Stryker, MI), have demonstrated efficacy. Studies have illustrated the ease of ICG administration directly into the urethra or through a urinary catheter for near-infrared fluorescence imaging during TaTME, with cadaveric material often used to optimise urethral visibility.

- Stereotactic navigation: Use stereotactic navigation for pelvic surgical procedures to improve functional and oncological outcomes. Notably, Atallah et al15 reported positive clinical, functional, and oncological results in three patients with advanced rectal cancer treated using stereotactic navigation, as evidenced by a 30-month follow-up period.

3.2 Anastomotic leakage

Anastomotic leakage is a significant concern following low anterior resection (LAR), presenting an incidence rate of 15.7% according to a multicentre study including 1594 patients undergoing TaTME.16 Of note is that cancer was present in 96.6% of all leaks, with an average distance from the serrated line of 3 cm.16 Surgeons used an anastomosis technique with a stapler in 66% of cases. The observed spectrum of leak types included early leak (7.8%), delayed leak (2.0%), pelvic abscess (4.7%), anastomotic fistula (0.8%), chronic sinus (0.9%), and anastomotic stenosis (3.6%). Independent risk factors for anastomotic leakage were male gender, obesity, smoking, diabetes, tumour size larger than 25 mm, significant intraoperative blood loss, manual anastomosis technique, and prolonged operating room time in the perineum.16

Prevention

- Prophylactic stoma: A 2019 meta-analysis of eight randomised studies investigated patients undergoing LAR, segregating them into two cohorts: those with a prophylactic stoma and those without. The analysis revealed that patients with a prophylactic stoma experienced significantly lower rates of leakage (6.3% vs 18.3%) and a reduced risk of reoperation (5.9% vs 16.7%) compared with their counterparts without a stoma.17

- Endoscopic sutures: In a 2023 study involving 51 patients undergoing TaTME, anastomosis was performed using the single-stapling method. Following this, reinforcing Z sutures were applied to envelop the suture line with rectal mucosa, as depicted in Figure 2.18 Remarkably, none of the patients exhibited any signs of leakage.

3.3 Vaginal and sacral venous plexus injuries

The incidence of vaginal and sacral venous plexus injuries is about 0.3%.19 Despite being less common than urethral lesions, they are important as the precise identification of the rectal septum could minimise deeper tissue damage.19

Challenges in preparation arise from factors such as anterior tumours, prior pelvic surgery, and radiation therapy, particularly when dissection is minimal, leading to difficulty in precisely identifying the position and accessing the rectal septum.

Prevention

Routine probing of the posterior wall can serve as a preventive measure against vaginal injuries.

Treatment typically involves the use of interrupted sutures, with plastic reconstruction being occasionally beneficial, especially in cases where manual execution of an anastomosis is required.

3.4 Damage to autonomic nerves

The occurrence rate of autonomic nerve damage is reported at 4.2%, resulting in dysfunction of the internal sphincter and sexual impairment. It is often caused by an indirect surgical approach, leading to permanent damage of the autonomic nerves.20

Prevention

A multicentre study conducted by Kneist et al20 demonstrated the efficacy of employing neurostimulation and imaging techniques to assess pelvic autonomic nerves, thereby avoiding such injuries. Electrophysiological confirmation of the external innervation of the internal sphincter, located proximate to the levator muscle, was critical. Electrodes positioned at the 5 o'clock position (internal sphincter) and the 8 o'clock position (external sphincter) facilitated this process (Figure 3).20 The study highlighted the superiority of the perianal technique with neurostimulation over the laparoscopic approach, exhibiting reduced induced dynamics. In addition, the identification of five critical risk areas potentially harmful to pelvic autonomic nerves was elucidated, with no reported complications among the patients.20

3.5 Carbon dioxide embolism

Although rare, CO2 embolism represents a potentially lethal complication during TaTME. In a retrospective study by Harnsberger et al,21 among 80 TaTME patients, 3 cases of CO2 embolism were documented.

Prevention

During the perianal phase, patients are positioned in the Trendelenburg position to reduce venous pressure. However, the confined space and insufflation pressures of 15 mm Hg increase the risk of venous bleeding and subsequent CO2 embolism. Vigilant monitoring of end-tidal CO2 and oxygen saturation is crucial to detect signs of intraoperative hypotension and cardiovascular collapse.

Immediate decompression of the pneumorectum and positioning the patient in a left Trendelenburg posture, coupled with meticulous bleeding control and saline irrigation of the surgical site, are vital steps in managing CO2 embolism.21 Furthermore, reports indicate that the use of suction during insufflation may exacerbate CO2 turbulence augmenting the risk of embolism.22

3.6 Disorder of intestinal function and sphincter mechanism

Total mesorectal resection (TME) may result in temporary or permanent impairment of pelvic organs, affecting the overall quality of life. The latest minimally invasive technique, of TaTME, raises concerns about potential further deterioration of genitourinary and anal functions.

Assessing the safety of TaTME necessitates a thorough examination of sphincters’ anatomical integrity and their role in continence, defecation, and urogenital functions. A study conducted in Denmark collected data from questionnaires including the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), LARS, ICIQ-MLUTS, ICIQ-FLUTS, IPSS, IIEF, SVQ, and FSFI. The study evaluated 115 TaTME procedures from August 2016 to April 2019 and 92 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic TME between January 2011 and September 2014. Although there was a transient decline in post-operative quality of life, long-term outcomes were comparable between groups. However, rectal dysfunction significantly ameliorated in TaTME patients (P < .001) compared with preoperative baseline at a mean follow-up of 13.5 months; 67.5% of TaTME patients reported low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) symptoms, including faecal incontinence, diarrhoea, and frequent bowel movements, which often ameliorated over time. Urinary function remained unaffected after TME across all surgical approaches, while sexual function data were lacking.23

In a recent Italian study involving 97 TaTME patients, 88.7% received prophylactic ileostomy and 25.8% experienced LARS symptoms during the 19-month follow-up. Statistical analysis revealed correlations between age, timing of intervention, duration until stoma reversal, and LARS severity. Prolonged surgery (>295 min) and delayed stoma reversal (>5.6 months) were associated with more severe LARS symptoms, especially in older patients (>65 years). No significant difference was observed in LARS occurrence between initial and subsequent cases.24

Prevention

- Precise staple insertion: Accurate insertion of staples through the anus is crucial.

- Preservation of rectal reflex: Minimise rectal tissue removal to safeguard the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, which typically recovers by the second year after surgery.

- Avoidance of mucosectomy: Mucosectomy should be avoided to preserve rectal innervation.

- Careful mesorectal preparation: Prepare the mesorectum in the vascular plane while preserving autonomic innervation. Avoid excessive lateral traction during preparation.

- Utilisation of laparoscopic and robotic surgery: Although claimed to preserve autonomic nerves, the benefits remain uncertain.

- Ischaemia and mesentery pulling: Be mindful of the combined effects of ischaemia at the anastomosis site, small descending colon size, and severe pulling on mesentery, which may impact post-surgical bowel function.

- Management of veins: Mobilising and ligating veins may disrupt inhibitory sympathetic innervation, leading to increased colonic movement and potential dysmotility, and thus contributing to low anterior resection syndrome (LARS).

- Importance of adequate mobilisation: Adequate mobilisation of the left buttock is necessary to achieve low anorectal anastomosis.

- Colonic neo-ampulla (J-pouch): Consideration of the colonic neo-ampulla, also known as the J-pouch or lateral-terminal anastomosis, is a surgical option to optimise outcomes.25

Implementing these preventive strategies is important for ensuring successful surgical interventions and minimising post-operative complications.

3.7 Abscess formation

Abscess formation following rectal surgery can occur through post-operative leakage or direct pelvic contamination during the perianal procedure phase, which poses a higher risk compared with standard TME approaches.

Research by Velthuis et al26 revealed that 39% of TaTME patients experienced post-surgical peritoneal bacterial infection, with 44% of abscesses developed in the presacral region.

Prevention

To attenuate the risk, preoperative rectal cleansing with an iodine solution is suggested. Ensuring airtight circulation and secure closure of the rectal lumen is crucial to prevent contamination and potential cancer cell spread within the rectum.27

4 LOCAL RECURRENCE RATES

- Technical challenges: TaTME is a complex procedure that demands high technical proficiency. Incomplete or inaccurate dissection of the mesorectal plane may leave behind residual cancer cells, increasing the likelihood of local recurrence.

- Learning curve: The steep learning curve associated with TaTME means that outcomes can vary widely among surgeons and institutions. Higher recurrence rates are often observed in centres with less experience.

- Patient selection: Inappropriate patient selection can lead to suboptimal outcomes. Patients with extensive local disease or advanced-stage cancer may not be suitable candidates for TaTME.

4.1 Risk attenuation strategies

- Enhanced training and experience: Ensuring that surgeons receive extensive training and gain sufficient experience is crucial. This includes participating in specialised training programs and workshops to master the technical aspects of TaTME.

- Standardised surgical protocols: Developing and following standardised protocols can help reduce variability in surgical technique and outcomes. Detailed guidelines on patient selection, intraoperative techniques, and post-operative care are essential.

- Multidisciplinary team approach: Involving a multidisciplinary team that includes surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists can optimise patient selection and perioperative management. This collaborative approach can help mitigate the risk of local recurrence.

- Ongoing monitoring and quality assurance: Continuous monitoring of surgical outcomes can identify fields for improvement. Tracking local recurrence rates and comparing them with benchmarks can help ensure quality control and improve overall outcomes.

In conclusion, TaTME represents a significant advancement in rectal surgery, offering improved access to tumours and facilitating a more thorough mesorectal removal. The integration of transanal and perineal access with minimally invasive surgical techniques has changed radically the management of rectal malignancies, especially in cases involving the narrow pelvis and perineum. TaTME requires extensive training and ongoing skill development among surgeons to minimise potential complications and ensure successful surgical interventions.

By providing enhanced visualisation of tumour location and addressing challenges associated with accurately predicting tumour volume, TaTME has the potential to optimise oncological outcomes and patients’ quality of life. Emphasising the importance of preventing adverse outcomes underlines the need for ongoing training and skill development among surgeons.

Through continuing research, training, and refinement of techniques, TaTME has the potential to further enhance the standards of care in colorectal surgery, and thus improve patient survival rates and quality of life.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.