Massive peritoneal inclusion cyst with secondary abscessation

Abstract

Peritoneal inclusion cysts are rare intra-abdominal cystic lesions of controversial pathogenesis and nomenclature. Postulated to be of neoplastic or reactive origin, they are characterised by progressive expansion and variable symptomatology in classically reproductive-aged females. Local recurrence is frequent while malignant transformation is plausible. Herein, we review a presentation of a massive peritoneal inclusion cyst with secondary abscessation and septic shock in a 58-year-old female, reviewing the available literature to highlight the potential acuity of this pathology, the standard of surgical care, and the need for caution by treating surgeons in its evaluation as an entirely benign process.

1 INTRODUCTION

First described by Mennemeyer and Smith in 1979,1 peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) are rare intra-abdominal lesions described infrequently within the literature for which accurate classification and delineation of treatment guidelines are limited by an incompletely characterised pathogenic model and controversial nomenclature. Also described as benign (multi-)cystic mesothelioma,2-5 mesothelial inclusion cysts,6 and post-operative peritoneal cysts,5 lesions typically display a preponderance for females of reproductive age and high recurrence rates. Cysts may be discovered incidentally, or may present acutely, necessitating urgent surgical intervention.

2 CASE REPORT

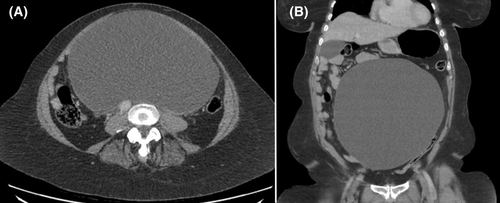

A 58-year-old female presented to our institution febrile, with a history of progressively severe abdominal pain, nausea, anorexia, and orthopnoea over a 2-year period, in the context of a known intra-abdominal cystic lesion for which she was awaiting outpatient surgical consultation. She had no history of prior intra-abdominal surgery or abdominopelvic pathology. Examination revealed a distended, diffusely tender abdomen with no evidence of peritonitis. Urgent computed tomography imaging with intravenous contrast demonstrated an anterior abdominal cystic structure measuring 24 × 15 × 24 cm with displacement of the duodenum and small bowel, and compression of the inferior vena cava (Figure 1).

A nasogastric tube was placed for decompression, and she was commenced on intravenous antibiotics for suspected intra-abdominal sepsis. The patient subsequently developed septic shock with rapid atrial fibrillation and Streptococcus dysgalactiae bacteraemia, requiring emergent midline laparotomy on day 2 of admission.

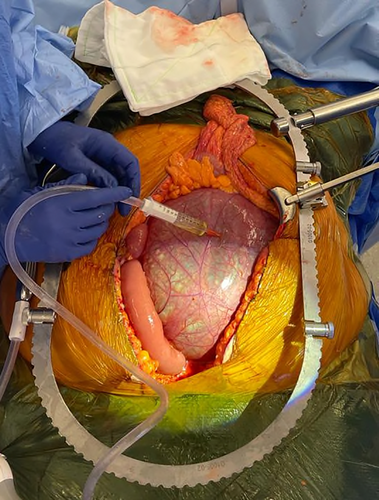

At operation, a sizeable midline cyst was found fixed to the duodenum, mesentery, and colonic splenic flexure without involvement of genitourinary structures. Its base was adherent to the vertebral column and aorta (Figure 2), limiting complete resection. The cyst was decompressed and opened to facilitate safe dissection, demonstrating serous fluid with dependent pus. Percutaneous drainage was considered, although deemed to provide insufficient source control given the acuity of this presentation.

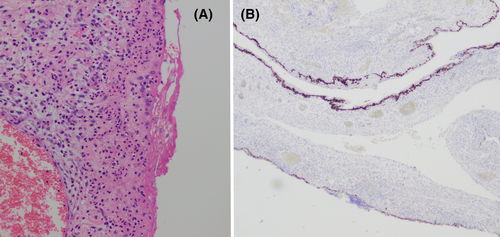

Cystic fluid aspirate revealed the growth of S. dysgalactiae, while histopathological analysis of the cyst wall demonstrated bland mesothelial-lined tissue with microabscessation and without atypia. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for calretinin, cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2 and negative for CDX2 and PAX8. An infected PIC was diagnosed (Figure 3). The patient's post-operative course was unremarkable.

3 DISCUSSION

PICs are infrequently encountered intra-abdominal cystic lesions displaying progressive mesothelial cell proliferation that often raise clinical suspicion of malignancy.7 With an estimated incidence of 0.15 per 100 000 persons,2 their rarity has thus far precluded a comprehensive scientific understanding. Nevertheless, affected individuals are typically females of reproductive age, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:18 and a reported average age of 32 years.5

Patients often possess a history of prior intra-abdominal surgery or chronic inflammatory diseases such as endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease, supporting a theory of cyst formation as reactive mesothelial hyperplasia.5, 7 Critically, there is no known association with asbestos exposure.3 As in our case, however, some patients have no medical history of note.5 Moreover, the developmental behaviour of cyst formation and high recurrence rate support a pathogenic theory of PICs as neoplastic phenomena driven by systemic hormonal influences on peritoneal mesothelial cells,2 sitting on a spectrum between adenomatoid tumours and malignant mesothelioma.5 While their bland histological morphology and indolent behaviour are characteristics of a benign process, malignant transformation in recurrent disease has been identified. Mirroring this controversy are the variety of terminologies often used interchangeably within the literature to describe this condition: benign (multi-)cystic mesothelioma,2-5 mesothelial inclusion cyst,6 and post-operative peritoneal cyst5 find common usage, causing confusion in the classification of what is otherwise a definite clinical entity, and impeding the adoption of uniform treatment guidelines. To limit associations with malignant mesothelioma, the World Health Organisation advocates for the use of (multi-loculated) peritoneal inclusion cyst(s).5

Approximately half of clinically evident PICs display indolent behaviour and are found incidentally during surgical intervention or abdominopelvic imaging.3, 8 The remainder may exhibit non-specific abdominal pain; a palpable abdominal mass; weight loss; and signs of compression to surrounding structures, including bowel obstruction, constipation, and early satiety.5 Patients may even present with a surgical abdomen.9 Sepsis secondary to cyst abscessation, as in our case, is uncommonly described.

Differential diagnoses include both benign and malignant conditions.9 Enteric duplication cysts should be suspected where there is an intimate relationship between the bowel and cyst wall, while lymphangiomas are typically found in male children.3 More troublesome differentials are appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, ovarian cystadenocarcinoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, sarcoma, and malignant mesothelioma.2, 3, 5

The typical imaging findings are a single cyst or multiple cysts arising typically from the serosal surface of abdominopelvic organs.5 They may be unilocular or multilocular, and may even float freely within the peritoneum.5, 7 The presence of peritoneal deposits, cyst calcification, and ascites should raise suspicion for malignant mesothelioma.5 While radiographic findings aid in the assessment of cyst localisation and involvement of surrounding structures, definitive diagnosis of PIC is ultimately by surgical resection and histopathological examination, which should be pursued in every case where there is suspicion of malignancy. The characteristic findings are fibrous walls of loose or collagenous connective tissue, lined by a single layer of flat, cuboidal, or columnar mesothelial cells,5, 7, 8 while stromal neutrophilic infiltrate and microabscess formation suggest secondary infection, as in our case. Immunohistochemical analysis typically reveals positive staining for calretinin, cytokeratin 5/6, cytokeratin CAM 5.2, and WT1,5, 10 while bland nuclear features, a low degree of cellular proliferation, and absence of atypia are key features distinguishing PIC from malignant mesothelioma.3 There is no clear association with elevated tumour markers such as CA 19.9 and CA 125.5

While no uniform management strategy has been delineated, early complete surgical resection where possible is the treatment of choice.2 In addition, some surgeons have advocated for complete cytoreductive surgery with heated intra-peritoneal chemotherapy in select scenarios to mitigate the risks of recurrence and malignant transformation. In similar cases, repercussions for fertility in this population should be considered.5 However, given the high recurrence rates (41%–50%),2, 5 a treatment goal of symptom control with cyst debulking surgery may be preferable, especially in cases such as ours where total resection is difficult and tissue planes poorly defined.5 Other options are long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone and oestrogen receptor modulation, which have yielded reduced cyst volume and growth in limited case studies.5 Ultimately, PICs demonstrate a typically benign course with an excellent prognosis limited by surgical morbidity, and the rare risk of malignant transformation.4, 8

4 CONCLUSION

In summary, PICs are rare intra-abdominal cystic lesions characterised by progressive growth and frequent recurrences for which surgical management is the standard of care. Controversy surrounding the true pathogenesis and a lack of long-term follow-up have hindered an accurate appraisal of this disease process, and the establishment of a uniform treatment approach. In similar cases, treating surgeons should remain cognisant of life-threatening differential diagnoses, and take caution in assessing PIC as an entirely benign process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Kim Tran (New South Wales Health Pathology). Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.