Bankruptcy Exemption, Home Equity and Mortgage Credit

Abstract

This article examines the impact of state bankruptcy homestead exemptions on mortgage application outcomes. The empirical analysis controls for endogeneity problems by focusing on 55 urban areas that cross state borders using the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act files from 2001 to 2008. The results indicate that holding the loan-to-value ratio constant, a more generous homestead exemption encourages borrowers to buy more housing and take out larger mortgages. However, holding house value constant, a more generous homestead exemption discourages mortgage borrowing and results in more home equity. Moreover, benefits of the homestead exemption outweigh the costs of it to mortgage lenders.

Since the financial crisis that started in late 2006, millions of households have lost, or are at risk of losing, their homes to foreclosure. Homeowners overwhelmed by their debt burdens could turn to personal bankruptcy for financial relief. State bankruptcy homestead exemption provisions specify the amount of home equity that homeowners are entitled to retain in the bankruptcy proceedings. The generosity of this homestead exemption differs across states and across time. In this article, I argue that homestead exemption provision might affect borrowers’ incentives to borrow and lenders’ exposure to credit risks. This study examines implications of these and related ideas in the context of the U.S. mortgage market.

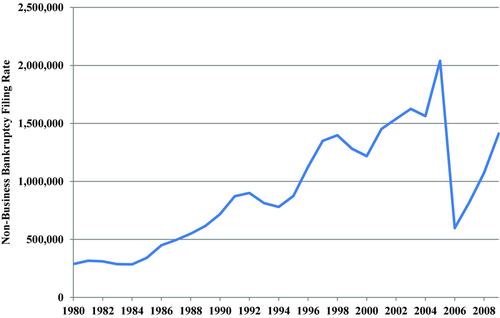

Figure 1 shows that personal bankruptcy filing rates in the United States increased dramatically between 1980 and 2008. This increase occurred despite the 2005 bankruptcy reform,1 which made filing for personal bankruptcy less appealing. The rise in personal bankruptcy filing rates over the past two decades has motivated research into how personal bankruptcy laws affect both the supply and demand sides of mortgage markets.

Particular attention has been devoted to the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage lenders, but the literature has failed to achieve agreement (e.g., Berkowitz and Hynes 1999, Lin and White 2001, Chomsisengphet and Elul 2006). On the one hand, the homestead exemption allows mortgage borrowers to shift resources from consumer debts toward mortgage debts and thereby helps them avoid mortgage default. Therefore, mortgage lenders are less likely to encounter late payments or mortgage default risks. On the other hand, mortgage borrowers are more likely to file for bankruptcy in states with a more generous homestead exemption. The bankruptcy filing stops all collection efforts, delays the foreclosure process and imposes additional transaction costs on mortgage lenders, such as lost mortgage interest and depreciated property value. When we allow for both possibilities, the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage lenders is potentially ambiguous. This article adds to the literature by examining the effects of state homestead exemption on lenders’ exposure to credit risks.

In contrast, the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage borrowers has not been studied as extensively in the literature. This article begins to fill that gap. The homestead exemption is unambiguously beneficial to mortgage borrowers and likely to increase the propensity of homeowners to retain wealth in the form of home equity. A higher homestead exemption directly protects debtors’ home equity from being taken away and encourages homeowners with more home equity to file for bankruptcy. In addition, the more generous the homestead exemption, the more funds borrowers are likely to have after filing for bankruptcy. This effect is known as the “wealth effect,” because it leaves borrowers with more funds to make their mortgage payments. Lastly, bankruptcy filing imposes an automatic stay on all collection efforts, including foreclosure sale. This allows borrowers to remain in their homes in the event of financial distress for a few months,2 so that homeowners who have fallen behind in their mortgage payments can get additional time to repay mortgage arrears and keep their homes.

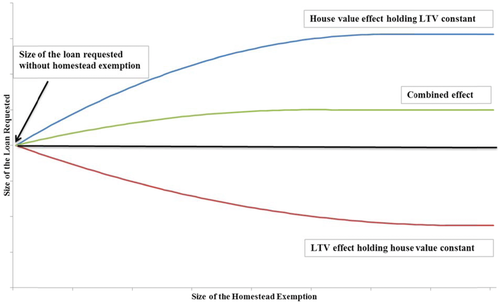

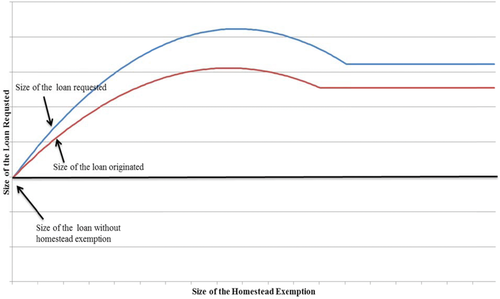

The core logic of this article rests on the assumption that risk-averse borrowers are aware of the protection provided by a homestead exemption in the bankruptcy proceedings before applying for mortgages. Therefore, a more generous homestead exemption will encourage homeowners to store a greater portion of wealth in the form of home equity ex ante. There are two possible mechanisms by which this might occur. One is the house value effect: a more generous homestead might encourage homeowners to purchase a more expensive home and request a larger mortgage for any given loan-to-value (LTV) ratio. The other is the LTV effect: a more generous homestead exemption might encourage borrowers to have a smaller LTV ratio and take out a smaller mortgage for any given value of a home. Therefore, the homestead exemption has offset effects on size of the loan sought by borrowers through these two different mechanisms.

The data that I draw upon are obtained from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) files from 2001 to 2008. In all cases, my unit of observation is the individual loan application. I have a set of dependent variables and a series of regressions. To assess the combined effects of the two mechanisms on mortgage demand, I regress the size of the loan requested on the level of the homestead exemption. I also measure the impact of the homestead exemption on size of the loan originated and lenders’ accept/reject decisions of loan applications. I restrict my samples to conventional, conforming-sized home purchase loans for the above analyses.

There are some additional parts of my article that help separate out the two mechanisms. I compare the impact of the state homestead exemption on home purchase loans with refinance loans, and I also compare the impact of the state provision on conforming-sized loans with nonconforming-sized/jumbo loans. The comparisons between different loans highlight different features of the model, and the details will be explained later.

Similar to Pence (2006), I use a border method by focusing on the 55 urban areas that cross state boundaries so that I can compare mortgage activities just on either side of state borders. This method helps control for unobserved local attributes that might be correlated with state-specific homestead exemption provisions. Urban area fixed effects are included to help identify the impact based on temporal variations in the homestead exemption within each individual urban area.

Results are largely consistent with what the model suggests. When I work with home purchase loans, especially for the conforming-sized loans, I cannot separately identify the two possible mechanisms by which the homestead exemption might possibly affect the size of the loan sought by borrowers and ultimately originated. What I can do is to instead identify the net effect of the two mechanisms. Results suggest the relationship between the size of the loan requested and the homestead exemption is nonlinear and hump-shaped. The size of the loan requested initially increases with the homestead exemption, reaches a peak and then declines until it reaches an asymptote. On net, a more generous homestead exemption tends to increase the size of the loan requested, which is suggestive of the house value effect dominating the LTV effect.

When focusing on the effect of the homestead exemption on the loan originated, instead of the loan requested, the results show a similar qualitative pattern but produce different point estimates. The differences between the coefficient estimates of the two regressions provide evidence of credit constraints, because the size of the loan that is originated is smaller than the size of the loan requested. Furthermore, results from the loan denial regression show that loan applications are less likely to be denied in a state with an unlimited homestead exemption than in a state with zero homestead exemption. This indicates that the difference between the borrower's preferred level of debt and the debt ceiling imposed by lenders is diminishing with the impact of homestead exemption. Borrowers tend to request a higher level of debt in a state with a more generous homestead exemption on net. It can be inferred from this finding of mine that the debt ceiling imposed by mortgage lenders reduces with the more generous homestead exemption. Thus, the mortgage lenders are willing to issue more mortgage credit in a state with a more generous homestead exemption.

When I work with refinance loans, I take the value of the home as exogenously given. For those loans and in comparison to home purchase loans, I test more explicitly the LTV effect. Estimates from the conforming-sized, refinance loan regression are consistent with what the model suggests. A more generous homestead exemption clearly reduces the size of the loan requested conditioning on existing homes, and that is indicative of the negative LTV effect on loan size.

I also compare the conforming-sized loans to jumbo loans. Jumbo loans are more expensive loans that are associated with higher value of homes. The estimates of the income elasticity of housing demand from the previous literature are mostly well below one.3 As an approximation, it is plausible that the impact of more generous homestead exemption probably has a more impact on LTV ratios as compared to encouraging borrowers to purchase some even more expensive homes. Therefore, I expect to see a more negative, less positive net effect as compared to conforming-sized loans. Estimates from jumbo home purchase loans suggest that the size of the loan requested decreases initially and keeps declining until it reaches an asymptote at the unlimited homestead exemption. This suggests that the LTV effect dominates the house value effect no matter how generous is the homestead exemption. Finally, I test the LTV effect again using jumbo refinance loans. Results further support that mortgage borrowers are willing to take out smaller refinance loans in a state with a more generous homestead exemption.

The plan for the rest of the article is as follows. The next section provides more background of U.S. bankruptcy law. The third section presents the conceptual framework. The fourth section describes the empirical model and identification strategy. The fifth section contains a description of the data. The sixth section presents the results, and the final section concludes.

U.S. Bankruptcy Law and Homestead Exemption

The U.S. bankruptcy law distinguishes between secured and unsecured debts. Secured debts, for example, mortgages and automobile loans, allow the creditor to reclaim the collateral if the debtor defaults on the loan. Unsecured debts, for example, credit card debts and medical bills, have no collateral for the creditor to seize. Because mortgage creditors have the right to foreclose on houses, regardless of whether debtors file for bankruptcy or not, they are in a much stronger position than unsecured creditors.

There are two separate procedures in U.S. bankruptcy law: Chapters 7 and 13. Prior to 2005, debtors were allowed to choose between them. Debtors who file under Chapter 7 are not obliged to use the future income to repay and are only obliged to repay debts out of their assets to the extent that their assets exceed the predetermined exemption levels. Personal bankruptcy is governed by federal law, but states can set their own asset exemption levels and have different exemptions for different assets. But in nearly all states, the homestead exemption for equity in an owner-occupied home is the largest.

Debtors who file under Chapter 13 are obliged to repay debt out of their income over a period of three to five years. Exemptions also have significance in Chapter 13 through the “best interest of the creditors” test, which states that the creditors are entitled to receive at least as much in Chapter 13 as they would have in received in Chapter 7. Thus, in a state with high exemptions, creditors should also expect repayments in Chapter 13.4 Therefore, I will ignore the differences between these two procedures in the following paper.

State homestead exemptions specify the amount up to which an individual's home equity is protected. If the home equity is below the state's homestead exemption, homeowners can keep their homes after filing for bankruptcy. If the home equity is above the state's homestead exemption, homeowners who file for bankruptcy must give up their homes for foreclosure sale by the bankruptcy trustee.5 The proceeds of selling the house are first used to pay the costs of foreclosure. Then, the money obtained from selling the home is used to repay the mortgage, as well as the second mortgage if there is one, in full. Next, an amount up to the homestead exemption is retained by the homeowner. Finally, the remainder is distributed to the remaining unsecured creditors. Hence, the homestead exemption is not likely to have a direct impact on the willingness of mortgage lenders to supply mortgage credit because mortgage lenders are senior to the homestead exemption in foreclosure.

Conceptual Framework

Overview

This section provides the conceptual framework that motives my hypotheses. I follow the model developed in Lin and White (2001) by integrating consumers’ decisions to default on their mortgages with their decisions to file for bankruptcy. The analysis is divided into two cases based on the value of the homestead exemption.

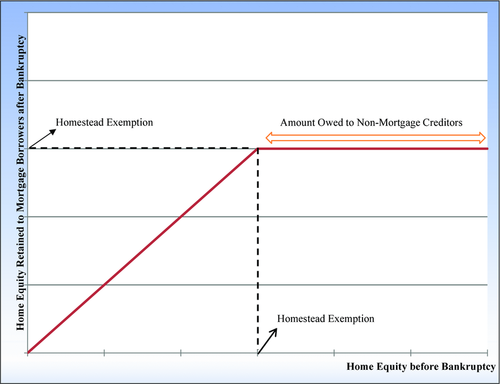

It is useful to emphasize that a difference in the level of the homestead exemption only matters when there is a positive home equity. Therefore, I only focus on situations when the home equity is positive and assume that there will not be any equity left for mortgage borrowers after the foreclosure proceeds are distributed among secured and unsecured lenders. In other words, I restrict my attention to the cases when the home equity is smaller than the sum of the home exemption and the debts owed to nonmortgage creditors.6 The relationship between home equity before filing for bankruptcy and home equity retained to mortgage borrowers after bankruptcy is illustrated in Figure 2. Each case is analyzed in detail as follows.

Different Cases

Case A: Homestead exemption greater than home equity

In this case, the homestead exemption is unlimited or finite and greater than the amount of the home equity. Homeowners may file for bankruptcy in order to have their unsecured debts discharged and then use the wealth gain to repay their mortgages and avoid selling their homes.7 All collection efforts are stopped during the bankruptcy proceeding, giving homeowners some additional time to shift funds from paying other debts to paying their mortgages. If they are current on the mortgage payments, they can keep their home after bankruptcy. Hence, they still have the incentive to maintain the home during the period. The larger the homestead exemption, the more likely the home is directly protected from being taken away by the bankruptcy trustee, and the more likely that the sale of the home and its corresponding costs can be avoided.8

Case B: Homestead exemption smaller than home equity

In this case, the homestead exemption is zero or positive but smaller than the amount of the home equity. Even though homeowners may have relatively large home equity, they may still file for bankruptcy to discharge large unsecured debts—perhaps because they own an incorporated business. Also, homeowners will not try to save their homes and stop paying mortgage payments. This is because even if they are current on the payments, the bankruptcy trustee will still foreclose their homes. Homeowners will take advantage of the automatic stay and remain in their homes for free. During that period, the homeowners will have no incentive to maintain the home and will therefore allow the home value to depreciate to the level where the home equity equals the homestead exemption. No matter how valuable the home is, they will only get the amount of the homestead exemption back after foreclosure, so the house is more likely to deteriorate. Lenders lose when foreclosure occurs,9 and they are not guaranteed to get the foregone interest and fees back.

Overall, the homestead exemption is beneficial to mortgage borrowers. Borrowers are better sheltered in the event of financial distress by a more generous homestead exemption. However, because the mortgage takes precedence over the state homestead exemption, no matter how large the exemption, if borrowers fail to keep up with their mortgage payments, mortgage lenders still have the right to foreclose on the houses.

House Value Effect and LTV Effect

Suppose that risk-averse borrowers are aware of the protection provided by the homestead exemption when they apply for mortgage credit. Berkowitz and Hynes (1999) conclude that the effect of the homestead exemption on the demand for mortgage is likely to be limited. They argue that the vast majority of mortgage borrowers are unaware of the magnitude of their state's exemption at the time of borrowing. It is possible that because the bankruptcy filing rates have been increasing in the past decades, the bankruptcy provisions have become more known to the public. Also, since the recent financial crisis, terms such as default, foreclosure and bankruptcy have become more popular in the media. Hence, it is reasonable to argue that mortgage borrowers will retain more wealth in the form of home equity in a state with a more generous homestead exemption.

As shown in Figure 3, there are two mechanisms through which mortgage borrowers could retain more home equity. One is through the house value effect: holding the LTV ratio constant, a more generous homestead exemption encourages homeowners to buy more expensive homes and request larger mortgages. The intercept of the house value effect curve is positive, indicating that even when the homestead exemption is zero, borrowers still request a certain amount of mortgage debt. The positively sloped curve tells us that holding the LTV ratio constant, the larger the homestead exemption, the larger the mortgage loan requested.

There are two possible reasons that the house value effect curve might flatten out and the mortgage opportunities might be constrained as the size of the homestead exemption increases. First, borrowers might be income constrained and/or wealth constrained when they increase mortgage debt in order to retain more home equity. As the mortgage size increases, it might reach the maximum purchase price that satisfies the income criteria10 and mortgage borrowers might face income constraints. At the same time, for a given LTV ratio, the downpayment required for purchasing the home increases as the mortgage size increases. Therefore, as the mortgage size increases, it might also reach the maximum purchase price that satisfies the wealth criteria11 and borrowers might face wealth constraints. Second, given that previous estimates of the income elasticity of housing demand are mostly well below one, housing demand should grow at a much slower rate than income. Also it is reasonable to believe that the marginal effect of income on housing demand is diminishing as income rises. Therefore, it is plausible that an increase in the level of the homestead exemption may have more impact on LTV ratios as compared to encouraging borrowers to buy even more expensive homes or take out larger mortgage loans. Therefore, it is expected that the house value effect might be modest when mortgage size is large and the curve will hit an asymptote when a marginal increase in the homestead exemption does not affect the size of the loan requested for a given LTV ratio.

LTV ratio and payment-to-income (P/I) ratio are two key factors that mortgage lenders will consider during the underwriting process.12 From a mortgage lender's point of view, a constant LTV ratio with a rise in downpayment would not lead to tightened underwriting standards. However, the payment-to-income (P/I) ratio increases for any given income and mortgage term as monthly payment increases. Mortgage borrowers are less likely to afford the mortgage payments, especially under special circumstances (i.e., job loss, divorce), and more likely to lose their homes that they are seeking to protect by the homestead exemption.13 Therefore, the homestead exemption as a debt protection provision may not provide real protection to mortgage borrowers. Mortgage lenders are also more likely to be exposed to default risks, and they may tighten their underwriting standards accordingly.

The other effect is the LTV effect: taking the value of the house that borrowers want to purchase as exogenously given, a more generous homestead exemption will discourage mortgage borrowing and result in a smaller LTV ratio. The curve for the LTV effect starts at the same point as the house value effect. This is because when the homestead exemption is zero, neither effect prevails and borrowers still request a certain amount of mortgage debt. The negatively sloped curve tells us that, holding house value constant, the larger the homestead exemption, the smaller the mortgage loans that the borrower will seek to obtain.

Similarly, the LTV ratio effect curve might flatten out and the mortgage opportunities might be constrained as the size of the homestead exemption increases. Borrowers might be wealth constrained but not income constrained through a decline in mortgage demand in order to attain more home equity. As the mortgage size decreases, the downpayment required for purchasing the home increases for a given house value. Therefore, borrowers might face wealth constraints and may not be able to meet the down payment requirements. However, the type of borrowers in this mechanism might not be the same as those in the previous mechanism. Those borrowers who try to increase their home equity by taking out larger mortgages and purchasing more expensive homes may be capital-constrained households in the normal parlance. But those borrowers who try to increase their home equity by taking out smaller mortgages might be capital rich households. These borrowers might choose to take out large consumer loans (which can be discharged after bankruptcy proceedings) and use the money to pay off a larger amount of mortgages so that their assets can be protected. Therefore, I expect that the LTV effect will also hit an asymptote when a marginal increase in the exemption does not affect the size of the loan requested for a given value of a home.

For the mortgage supply side, changes that are associated with the LTV effect will not lead to a tightening of underwriting standards by mortgage lenders if the homestead exemption becomes more generous. The P/I ratio decreases for any given income and mortgage term, and the LTV ratio decreases as well. Therefore, mortgage lenders are less likely to be exposed to default risks and they will not tighten their underwriting standards.

Empirical Model and Identification Strategy

Testable Hypotheses

The homestead exemption may affect both the mortgage demand and the mortgage supply. This section develops these ideas and several related implications that can be tested with my data.

Note first that individual mortgage demand depends on the mortgage rate and the individual applicant's characteristics. In a local mortgage market, each mortgage applicant is a price taker of the local mortgage rate. Therefore, the size of the loan requested by a mortgage applicant can be treated as a proxy for individual mortgage demand. The discussion in the “Conceptual Framework” section suggests that the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage demand is determined by both the house value effect and the LTV effect. Hence, the overall impact of the homestead exemption on the size of the loan requested is potentially ambiguous. The direction and the magnitude of the impact will depend on the relative strengths of the two effects. I regress the size of the loan requested on the level of the homestead exemption to test this implication.

Three different robustness tests are then explored to help separate out the house value effect and the LTV effect. The first tests the LTV effect holding house value constant by using conventional, conforming-sized refinance loans. A refinance loan indicates that the mortgage borrower already has a home and the house value can be treated as exogenously given. For these loans and in comparison to conventional, conforming-sized home purchase loans, I test more explicitly the LTV effect. Because individual house value or the LTV ratio at origination is not available in HMDA, the house value is proxied using the median size of the conventional, conforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract where the loan is located. It is expected that the size of the refinance loan requested will decrease as the homestead exemption increases.

The second robustness test concerns the high-risk segment of the market. I repeated the exercises for conventional, nonconforming-sized home purchase loans. For nonconforming-sized loans, these are more expensive loans that are associated with high value of homes. It is worth emphasizing that previous estimates of the income elasticity of housing demand are mostly well below one. This indicates that housing demand should grow at a much slower rate than income. Also it is reasonable to believe that the marginal effect of income on housing demand is diminishing as income rises. Hence, it is plausible that an increase in the level of the homestead exemption may have more impact on LTV ratios as compared to encouraging borrowers to buy even more expensive homes or take out larger mortgage loans. This suggests that the house value effect might be modest and the LTV effect will dominate for the nonconforming-sized loans.

Symmetrically, the third robustness test analyzes the LTV effect again using conventional, nonconforming-sized refinance loans. For similar reasons, a negative LTV effect should be expected conditioning on existing and expensive homes. For this subsample, the house value is proxied using the median size of the conventional, nonconforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract where the loan is located.

The overall impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage supply is also ambiguous, as I discussed in the introduction. However, I cannot test the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage supply directly. Assume that borrowers may face binding borrowing constraints14 and a mortgage application is denied if mortgage borrowers request a larger loan than mortgage lenders are willing to issue.15 The changes in the difference between the borrowers’ preferred level of loan and the debt ceiling imposed by lenders will affect the likelihood that the loan is denied or not. Allowing for the possibility of credit constraint even without the homestead exemption, I also measured the impact of the homestead exemption on size of the loan originated and lenders’ accept/reject decisions of loan applications. These results help explain the impact of the homestead exemption on mortgage supply.

Estimation Equations

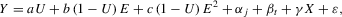

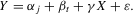

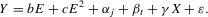

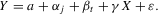

The discussion above suggests three regressions for conforming-sized home purchase loans and refinance loans, as well as nonconforming-sized home purchase loans and refinance loans. These are (i) the impact of the homestead exemption on the size of the loan requested, (ii) the impact of the homestead exemption on the size of the loan originated and (iii) the impact of the homestead exemption on the probability of loan denial.

(1)

(1) is the urban area fixed-effects,

is the urban area fixed-effects,  is the time-fixed effects, and X are a set of other relevant variables.

is the time-fixed effects, and X are a set of other relevant variables. (2)

(2) (3)

(3) (4)

(4)Therefore, coefficient a captures the differences in impacts between unlimited exemption and zero exemption, coefficient b captures the marginal effect of finite homestead exemption, and coefficient c captures potential nonlinearity in the regression as I have already discussed.

As described in the introduction, the urban area fixed effects control for time-invariant area characteristics, such as proximity to amenities, and capture the effects of variations in homestead exemptions across states within a given urban area and changes in homestead exemptions within a given urban area. The time fixed effects take into account time-varying effects that are common to all urban areas, such as national economic recession and capture the effects of variation across states in homestead exemptions. I also add an assortment of state-level, county-level and tract-level variables in order to directly control for the within urban area time-varying, area-specific characteristics. The detailed explanations of these variables are in the “Data” section.

Identification Strategy

There are two primary challenges that arise in the empirical analysis. First, it is difficult to identify the impact of state bankruptcy policy on mortgage markets because the laws and factors that affect mortgage markets vary dramatically by region. In a simple cross-sectional regression, a regional shock to the mortgage market might be misinterpreted as an effect of the state bankruptcy laws. The second challenge is the potential endogeneity associated with changes in the homestead exemption levels. If differences in the exemption level, or changes to the exemption level, are driven by unobserved local attributes, then the estimates produced will be biased.

Similar to Pence (2006), I control for both issues by using a border methodology and focus only on the 55 urban areas that cross state boundaries. I assume that mortgage applications in the census tracts that are within the same urban areas but located in adjacent states are quite similar. Therefore, mortgage applications in these census tracts are subject to different state bankruptcy exemptions, but the proximity of the homes assures that they have similar unobserved local attributes. By including urban area fixed effects, I am able to remove the time-invariant unobserved attributes that are specific for each urban area. The model also includes year fixed effects to control for time-varying effects that are common to all urban areas.

I have included a set of state-level, county-level, tract-level and loan-level characteristics as control variables in my regressions. The observed characteristics in a smaller geographic area than an urban area (i.e., county-level, tract-level and loan-level) are included in the model because variations in those levels will not be captured by the urban area fixed effects and are essential for loan application outcomes. Some state-level variables are also included in the model to control for relevant state policies (i.e., judicial foreclosure and deficiency judgment) and macroeconomic conditions (i.e., personal bankruptcy filing rate in the previous year).18

In addition, by focusing on the border areas, which are only a small portion of each state, I can assume that the border areas are not large enough to drive the changes in the state-level policy, thus making the policy changes exogenous. Furthermore, I can assume that the state-level homestead exemption is exogenous to the credit worthiness of the local residents in the border areas, which helps to deal with the concern in Chomsisengphet and Elul (2006).19

Finally, in order to further valid the border method, I have run regressions based on a sample from all metropolitan areas as a benchmark to that of the primary border area sample.20 Without accounting for the possible endogeneity arising from unobserved local attributes, the results based on conforming-sized loans using the sample of the whole metropolitan areas do not provide consistent coefficients for the unlimited homestead exemption variable and the finite homestead exemption variable.21 Also the results based on nonconforming-sized loans using the sample of the whole metropolitan areas suggest smaller negative effects of the homestead exemption than those using the sample of the border areas.22 Although the overall impact of the homestead exemption on the size of the loan requested is theoretically ambiguous as explained in the section “Conceptual Framework,” the differences in the estimates based on different samples may suggest that the regression results are biased if we don't account for the endogeneity problem.

Data

Geography

Following Pence (2006), I mainly focus on 184 metropolitan23 counties located within the 55 county groups that cross state lines in the United States. In order to see how representative the sample of the border areas is, I have compared the summary statistics of the border areas to those of the inner metropolitan areas that do not cross state borders in a later section. Regressions based on the sample from all metropolitan areas have also been run as a benchmark to those of the primary border area sample.

HMDA Data

The primary data used in the analysis were obtained from the HMDA. Specifically, I drew upon the HMDA data for each year from 2001 to 2008. Throughout the analysis, I retained only conventional loan applications for owner-occupied properties. I excluded loan applications that were withdrawn, incomplete or approved but not originated.24 I also deleted loan applications in which the applicant claimed to have zero income. Because the sample sizes are large, I selected a random sample of 10% of all applications each year.

When estimating the combined effect of homestead exemption on the size of the loan requested, I restricted my sample to home purchase loan records for which the size of the loan requested was less than the conforming loan limit stipulated by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in each given year. When estimating the LTV effect holding house value constant as a robustness test, I restricted my sample to conforming-sized refinance loans. In addition, the median size of the conventional, conforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract where the loan is located was used as a proxy for the house value. This was done because the HMDA data do not provide a direct measure of the individual house value at origination. I also used nonconforming-sized home purchase loans for another robustness test. The house value effect is expected to be small for jumbo loans. Finally, I tested the LTV effect again using conventional jumbo refinance loans. For this subsample, the house value is proxied using the median size of the conventional, nonconforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract where the loan is located.

Homestead Exemption

There are substantial differences in the generosity of the homestead exemption from state to state across the United States. The homestead exemption ranges from zero or a few thousand dollars to unlimited. Each state's homestead exemption in 2008 is listed in Table 1. Despite popular belief, no homestead exemption is truly “unlimited.” This is because all the homestead exemptions that do not contain dollar limits have a limit on lot size.25 For simplicity, I assumed that mortgage debtors have homes that do not have binding acreage limitations.

| State | Homestead Exemption | State | Homestead Exemption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 5,000 | Montana | 250,000 |

| Alaska | 67,500 | Nebraska | 60,000 |

| Arizona | 150,000 | Nevada | 550,000 |

| Arkansas | Unlimited | New Hampshire | 100,000 |

| California | 50,000 | New Jersey | 0 |

| Colorado | 60,000 | New Mexico | 60,000 |

| Connecticut | 75,000 | New York | 50,000 |

| Delaware | 50,000 | North Carolina | 18,500 |

| DC | Unlimited | North Dakota | 80,000 |

| Florida | Unlimited | Ohio | 5,000 |

| Georgia | 10,000 | Oklahoma | Unlimited |

| Hawaii | 20,000 | Oregon | 30,000 |

| Idaho | 100,000 | Pennsylvania | 0 |

| Illinois | 15,000 | Rhode Island | 300,000 |

| Indiana | 15,000 | South Carolina | 50,000 |

| Iowa | Unlimited | South Dakota | Unlimited |

| Kansas | Unlimited | Tennessee | 5,000 |

| Kentucky | 5,000 | Texas | Unlimited |

| Louisiana | 25,000 | Utah | 20,000 |

| Maine | 35,000 | Vermont | 75,000 |

| Maryland | 0 | Virginia | 5,000 |

| Massachusetts | 500,000 | Washington | 125,000 |

| Michigan | 34,450 | West Virginia | 25,000 |

| Minnesota | 300,000 | Wisconsin | 40,000 |

| Mississippi | 75,000 | Wyoming | 10,000 |

| Missouri | 15,000 |

Note

- This table reports state-specific homestead exemptions across the United States in 2008. Money values are in 2008 dollars.

The homestead exemptions not only vary across states but also across time. Even though some states kept their homestead exemption constant over the sample period, many states did change their homestead exemption, even after adjusting for inflation.26 For example, the homestead exemption in Massachusetts changed from $100,000 in 2001 to $300,000 in 2002, and changed from $300,000 in 2004 to $500,000 in 2005. I construct a panel for the homestead exemption variable from 2001 to 2008.

About one-third of the states allow residents to choose between a uniform federal bankruptcy exemption and the state bankruptcy exemption. In these states, I assume that the homeowners choose the higher homestead exemption when filing for bankruptcy. The homestead exemption also depends on the characteristics of debtors. Some states allow married couples to have a higher homestead exemption, which usually doubles when they file jointly. Because HMDA does not have information about the applicant's marital status, I assumed the applicants that have co-applicants are married. I doubled the homestead exemptions for the applicants with co-applicants who live in states that allow this type of adjustment. Some states also specify larger exemptions for senior citizens, veterans, the disabled, heads of family and debtors with dependents. To make it simple, I ignored the possibilities that the debtors might qualify for these special treatments.

Census Data

Data on neighborhood characteristics are obtained from the year 2000 census. The census data provide tract-level measures of the socio-demographic and economic variables. These include income, racial composition, education characteristics, unemployment, poverty status, population density and characteristics of housing stocks.

State- and County-Level Controls

I controlled for a set of state- and county-level variables. First, I included two state foreclosure law variables27 whose effects on mortgage markets are analyzed in Pence (2006): whether judicial foreclosure process is required and whether deficiency judgment is allowed.28 The judicial foreclosure variable is one if the state has a foreclosure process in which lenders must proceed through the courts to foreclose on a property. This restriction imposes large costs on mortgage lenders, so the lenders may respond by reducing mortgage supply. Borrowers may also respond to the benefits embedded in the law by demanding larger mortgages. The deficiency judgment variable is one if the state allows creditors to collect a deficiency judgment equal to the lender's foreclosure loss against the borrower's other assets. Although deficiency judgment is not often pursued in practice, it is a threat to mortgage borrowers and a protection to lenders.

In addition, I included each state's nonbusiness bankruptcy filing rate per 1,000 people in the previous year. This is included because it may take less time for borrowers to become informed about bankruptcy if there are more people filing in the applicant's state of residence in the previous year. Also, creditors may use last year's bankruptcy filing rate to predict future default rates in the state. The data were obtained from the American Bankruptcy Institute website.

The income tax rate may also influence a borrower's demand for home purchase loans. The higher the income tax rate, the larger the incentive for borrowers to seek a mortgage interest deduction and the larger the demand for mortgage debts. The actual income tax rate on a taxpayer is endogenous, i.e., it depends upon her or his income, age, education and other characteristics. However, we can assume that the maximum income tax rate29 by state and year is a nice independent variable that is representative of tax rates on property income and is independent of individual decisions. I did not include the maximum income tax rate variable in the refinance loan regression, because interests paid to refinance a mortgage are generally not deductible in full in the year in which they are paid.

I also included several county-level controls. I obtained the yearly unemployment rate from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Areas with high unemployment rates may be viewed as high-risk locations by lenders. In addition, I calculated the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)30 of mortgage markets at the county level using the HMDA data. The HHI captures the local market competition among lenders. The competitiveness of the local mortgage industry might influence borrowers’ access to mortgage credit and lenders’ willingness to issue credit. Intense competition for mortgage business might lead to an excess of lending and a weakening of underwriting standards. Therefore, the more competitive the local mortgage industry, the larger the size of the loan requested and the less likely the loan is credit rationed.

Table 2 provides the summary statistics for the variables in the regressions using year 2008 data only.31 I extend my sample to include the metropolitan areas that do not cross state borders.32 I compare the characteristics at state-level, county-level, tract-level and loan-level of the border areas to those of the nonborder areas. In general, the summary statistics at various levels of the border areas and the nonborder areas are very similar. Therefore, the data of the border areas are quite representative of the whole metropolitan areas.

| Border Areas | Nonborder Areas | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | St. Dev. | Obs. | Mean | St. Dev. |

| State Policy Variables | ||||||

| Homestead exemption level1 | 36 | 84,690 | 128,876 | 43 | 81,536 | 121,989 |

| Unlimited homestead exemption | 43 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 51 | 0.16 | 0.37 |

| Foreclosure must go through the courts | 43 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 51 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Deficiency judgment allowed | 43 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 51 | 0.84 | 0.37 |

| Maximum income tax rate | 43 | 5.09 | 2.78 | 51 | 5.09 | 2.86 |

| State-level controls | ||||||

| Nonbusiness bankruptcy filing in prior year | 43 | 2.80 | 1.17 | 51 | 2.62 | 1.17 |

| County Level Controls | ||||||

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of lenders | 184 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2,917 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| Unemployment rate in the current year | 184 | 5.62 | 1.34 | 2,917 | 5.97 | 2.06 |

| Census Tract Data from Census 2000 | ||||||

| Percent age 15–29 | 12,500 | 19.89 | 7.16 | 51,675 | 20.60 | 8.82 |

| Percent age 30–54 | 12,500 | 37.57 | 5.46 | 51,675 | 36.43 | 6.28 |

| Percent age 50 or more | 12,500 | 21.33 | 7.54 | 51,675 | 21.93 | 9.41 |

| Percent age 65 or more | 12,504 | 12.71 | 6.15 | 51,845 | 13.08 | 7.50 |

| Percent female | 12,500 | 51.65 | 3.45 | 51,675 | 50.86 | 4.38 |

| Percent Black | 12,504 | 17.90 | 27.78 | 51,845 | 13.16 | 22.70 |

| Percent Hispanic | 12,504 | 9.62 | 17.25 | 51,845 | 11.78 | 19.21 |

| Percent some high school | 12,500 | 13.08 | 8.24 | 51,668 | 13.62 | 7.71 |

| Percent high school graduates | 12,500 | 30.62 | 10.64 | 51,668 | 31.23 | 10.81 |

| Percent some college | 12,500 | 21.12 | 6.33 | 51,668 | 22.60 | 6.94 |

| Percent college or higher | 12,500 | 27.91 | 19.41 | 51,668 | 23.87 | 17.30 |

| Average income | 12,490 | 86,933 | 45,583 | 51,523 | 75,618 | 36,652 |

| Tract income relative to MSA | 12,490 | 1.02 | 0.47 | 51,523 | 0.99 | 0.40 |

| Average house value | 12,473 | 160,200 | 122,100 | 51,330 | 142,928 | 124,328 |

| Median rent | 12,456 | 879.89 | 316.78 | 51,402 | 802.47 | 325.59 |

| Population density (pop./sp. mi. land area) | 12,504 | 6,702 | 11,602 | 51,829 | 4,415 | 9,353 |

| Percent unemployed | 12,504 | 6.40 | 6.04 | 51,845 | 6.44 | 5.71 |

| Percent owner-occupied | 12,497 | 61.30 | 23.49 | 51,594 | 60.30 | 21.51 |

| Loan Applicant Attributes from HMDA | ||||||

| Loan amount of home purchase loans | 62,269 | 241,085 | 195,869 | 264,545 | 226,847 | 266,350 |

| Loan amount of refinance loans | 132,955 | 211,925 | 167,472 | 516,286 | 208,506 | 271,192 |

| Income | 221,990 | 100,685 | 134,814 | 817,700 | 94,501 | 134,157 |

| Black | 221,990 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 882,944 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| Hispanic | 221,990 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 882,944 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Female | 221,990 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 882,944 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

| Co-applicant | 221,990 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 882,944 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

Note

- This table provides summary statistics for the subsample of the metropolitan areas that cross state boundaries and subsample of the inner metropolitan areas that do not cross state boundaries in 2008. State-level, county-level, tract-level and loan-level data are reported separately. Money values are in 2008 dollars.

- 1Finite homestead exemptions only.

Results

Overview

Table 3 presents the estimation results of the conforming-sized home purchase loan regression and examines the effect of homestead exemption on the size of the loan requested, the size of the loan originated and the probability of loan denial, respectively. Table 4 presents the estimation results of conforming-sized refinance loan regression. Table 5 presents the estimation results of the nonconforming-sized home purchase loan regression. Table 6 presents the estimation results of the nonconforming-sized refinance loan regression. In all cases, t-ratios are reported based on clustering at the census-tract level.33 Both models include urban area fixed effects and time fixed effects and an extensive list of socioeconomics attributes at different geographic levels.

| Size of Loan | Size of Loan | Whether Loan Has | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requested | Originated | Been Denied | |

| Unlimited homestead exemption | 3.1956 | 2.5682 | –0.0206 |

| (1.82) | (1.35) | (–4.05) | |

| Homestead exemption level | 0.0323 | 0.0247 | 1.51E-05 |

| (in $1,000)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (6.48) | (3.55) | (0.41) |

| Homestead exemption squared | –6.16E-05 | –4.90E-05 | 9.90E-09 |

| (in $1,000)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (–3.63) | (–2.79) | (0.18) |

| Foreclosure must go through | –8.1742 | –8.9763 | –0.0032 |

| the courts | (–7.01) | (–7.03) | (–0.84) |

| Deficiency judgment allowed | 4.5866 | 4.6138 | –0.0137 |

| (1.47) | (1.44) | (–1.62) | |

| Maximum income tax rate | 0.8003 | 0.7829 | 0.0004 |

| (5.17) | (4.88) | (0.79) | |

| Nonbusiness bankruptcy filings | –3.4998 | –3.8644 | –0.0028 |

| in prior year | (–15.30) | (–16.00) | (–3.27) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | –50.0706 | –44.6172 | –0.0468 |

| of lenders | (–7.76) | (–6.43) | (–1.82) |

| Unemployment rate in the | –2.0285 | –1.9721 | 0.0003 |

| current year | (–6.38) | (–5.87) | (0.30) |

| Percent age 15–29 | 0.0180 | 0.0812 | –0.0027 |

| P(0.18) | (0.79) | (–10.86) | |

| Percent age 30–54 | 1.1581 | 1.1744 | –0.0051 |

| (8.85) | (8.71) | (–14.37) | |

| Percent age 55 or more | 1.1122 | 1.2005 | 0.0007 |

| (6.67) | (6.90) | (1.84) | |

| Percent age 65 or more | –0.9601 | –1.0538 | –0.0044 |

| (–5.02) | (–5.17) | (–9.36) | |

| Percent female | –1.0540 | –1.2161 | –0.0010 |

| (–8.11) | (–9.04) | (–2.43) | |

| Percent African American | –0.0781 | –0.0679 | 0.0010 |

| (–3.96) | (–3.12) | (16.44) | |

| Percent Hispanic | 0.0383 | 0.0483 | 0.007 |

| (1.06) | (1.29) | (7.57) | |

| Percent some high school | –0.8539 | –0.8035 | 0.0043 |

| (–10.43) | (–9.46) | (17.20) | |

| Percent high school graduates | –0.7758 | –0.7471 | 0.0012 |

| (–15.38) | (–14.73) | (9.50) | |

| Percent some college | –0.4491 | –0.4970 | –0.0008 |

| (–6.34) | (–6.75) | (–4.09) | |

| Average income | –0.2002 | –0.1692 | 0.0012 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (–5.42) | (–4.55) | (14.28) |

| Average house value | 0.1384 | 0.1337 | –0.0002 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (17.23) | (16.47) | (–14.77) |

| Median rent | 0.0030 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 |

| (2.12) | (0.95) | (0.51) | |

| Tract income relative to MSA | 0.0829 | 0.0620 | –0.0006 |

| (3.34) | (2.48) | (–10.58) | |

| Percent unemployed | 0.4880 | 0.3240 | 0.0004 |

| (5.23) | (3.37) | (1.14) | |

| Population density (pop./sq. | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | –5.89E-07 |

| mi. land area) | (1.23) | (1.14) | (–4.13) |

| African American | 3.4117 | 3.5967 | 0.0777 |

| (14.43) | (11.74) | (64.15) | |

| Hispanic | 0.5512 | 0.6589 | 0.0240 |

| (1.27) | (1.29) | (10.83) | |

| Female | –8.7870 | –10.2438 | –0.0041 |

| (–66.07) | (–64.46) | (–5.98) | |

| Co-applicant | 15.4975 | 15.0029 | –0.0782 |

| (122.74) | (101.18) | (–120.86) | |

| Income (in 1,000 dollars) | 0.0936 | 0.0983 | –0.0001 |

| (168.14) | (151.96) | (–22.75) | |

| Loan amount/income ≥ 3 | – | – | –0.0004 |

| – | – | (–0.34) | |

| Urban area fixed effects | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| Time fixed effects | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

| Observations | 645,315 | 534,194 | 645,315 |

Note

- The empirical specification is as follows:

- where dependent variable Y is the size of the loan requested for the loan demand regression, or the equilibrium loan size for the loan origination regression, or the probability of the loan being denied for the loan denial regression. U is one if the applicant lives in a state with unlimited homestead exemption, E is the finite homestead exemption, E2 is the quadratic term of the finite homestead exemption,

is the urban area fixed-effects,

is the urban area fixed-effects,  is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on conforming-sized home purchase loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on conforming-sized home purchase loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

| Size of Loan | Size of Loan | Whether Loan Has | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requested | Originated | Been Denied | |

| Unlimited homestead exemption | −3.2464 | −2.8936 | −0.0186 |

| (−3.02) | (−2.43) | (−3.78) | |

| Homestead exemption level | −0.0094 | −0.0192 | −1.50 E−05 |

| (in 1,000 dollars)*(1−unlimited homestead exemption) | (−1.53) | (−2.98) | (−0.59) |

| Homestead exemption level | 4.73E-05 | 5.72E-05 | 1.64E-07 |

| squared (in 1,000,000 dollars)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (4.73) | (5.46) | (4.08) |

| Foreclosure must go through | −5.9746 | −7.3705 | 0.0218 |

| the courts | (−10.00) | (−10.96) | (7.56) |

| Deficiency judgment allowed | 0.6232 | 1.1549 | −0.0405 |

| (0.41) | (0.72) | (−6.22) | |

| Nonbusiness bankruptcy filing | −2.4062 | −2.5708 | 0.0108 |

| in prior years | (−16.02) | (−15.08) | (15.60) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | −50.0927 | −44.4092 | 0.0780 |

| of lenders | (−10.48) | (−7.54) | (3.40) |

| Unemployment rate in the | −1.5217 | −1.9030 | 0.0041 |

| current year | (−9.14) | (−10.24) | (5.79) |

| Percent age 15–29 | −0.0531 | −0.0667 | −0.0027 |

| (−1.03) | (−1.14) | (−13.25) | |

| Percent age 30–54 | 0.7390 | 0.8227 | −0.0047 |

| (10.47) | (10.42) | (−16.28) | |

| Percent age 55 or more | 0.6709 | 0.5820 | −0.0043 |

| (8.36) | (6.38) | (−12.88) | |

| Percent age 65 or more | −0.5835 | −0.4750 | 0.0916 |

| (−6.12) | (−4.51) | (2.30) | |

| Percent female | −0.2672 | −0.3600 | −0.0012 |

| (−3.44) | (−4.07) | (−3.64) | |

| Percent African American | −0.0589 | −0.0446 | 0.0015 |

| (−5.70) | (−3.65) | (33.09) | |

| Percent Hispanic | 0.2487 | 0.2258 | 0.0008 |

| (12.03) | (9.97) | (10.18) | |

| Percent some high school | −0.2070 | −0.1574 | 0.0034 |

| (−4.85) | (−3.25) | (18.30) | |

| Percent high school graduates | −0.2592 | −0.3032 | 0.0016 |

| (−10.28) | (−10.93) | (15.99) | |

| Percent some college | −0.0354 | −0.1084 | 0.0009 |

| (−0.97) | (−2.67) | (6.16) | |

| Average income | −0.0130 | 0.0065 | 0.0005 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (−0.66) | (0.32) | (6.99) |

| Average house value | 0.0499 | 0.0526 | −0.0001 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (12.13) | (12.07) | (−9.47) |

| Median rent | 0.0029 | 0.0024 | 1.97E−05 |

| (3.56) | (2.73) | (6.89) | |

| Tract income relative to MSA | 0.0549 | 0.0296 | −0.0002 |

| (4.37) | (2.24) | (−4.35) | |

| Percent unemployed | −0.1390 | −0.0432 | 0.0322 |

| (−2.33) | (−0.66) | (1.40) | |

| Population density (pop./sq. | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | −7.24E−07 |

| mi. land area) | (7.05) | (6.27) | (−6.04) |

| African American | 6.4034 | 7.2811 | 0.0369 |

| (18.31) | (16.25) | (15.29) | |

| Hispanic | −0.2511 | −0.0878 | 0.0120 |

| (−0.47) | (−0.14) | (3.83) | |

| Female | −7.0870 | −8.5987 | −0.0196 |

| (−42.82) | (−41.42) | (−20.07) | |

| Co-applicant | 8.4210 | 6.0739 | −0.0954 |

| (44.65) | (26.61) | (−103.09) | |

| Income (in 1,000 dollars) | 0.2233 | 0.2736 | −2.36E−05 |

| (57.56) | (46.22) | (−3.32) | |

| Median size of the | 0.4690 | 0.4584 | −0.0009 |

| conforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract | (92.28) | (82.26) | (−49.33) |

| Loan amount/income ≥ 3 | − | − | 0.0865 |

| − | − | (77.17) | |

| Urban area fixed effects | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| Time fixed effects | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| R2 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.11 |

| Observations | 1,378,053 | 952,963 | 1,378,053 |

Note

- The empirical specification is as follows:

- where dependent variable Y is the size of the loan requested for the loan demand regression, or the equilibrium loan size for the loan origination regression, or the probability of the loan being denied for the loan denial regression. U is one if the applicant lives in a state with unlimited homestead exemption, E is the finite homestead exemption, E2 is the quadratic term of the finite homestead exemption,

is the urban area fixed-effects,

is the urban area fixed-effects,  is the time-fixed effects, and X are a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on conforming-sized refinance loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

is the time-fixed effects, and X are a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on conforming-sized refinance loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

| Size of Loan | Size of Loan | Whether Loan Has | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requested | Originated | Been Denied | |

| Unlimited homestead exemption | −157.7643 | −188.3029 | −0.0527 |

| (−4.21) | (−4.04) | (−4.20) | |

| Homestead exemption level | −0.4168 | −0.4073 | 6.75E−05 |

| (in $1,000)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (−2.59) | (−2.22) | (0.92) |

| Homestead exemption squared | 6.97E-05 | 7.14E-05 | −8.93E−08 |

| (in $1,000)*(1−unlimited homestead exemption) | (3.04) | (2.73) | (−0.79) |

| Foreclosure must go through | 36.6273 | 40.8995 | 0.0153 |

| the courts | (1.32) | (1.24) | (1.24) |

| Deficiency judgment allowed | −1.0485 | −2.3035 | −0.0249 |

| (−0.02) | (−0.04) | (−1.12) | |

| Maximum income tax rate | −3.8422 | −4.5151 | 0.0018 |

| (−0.64) | (−0.64) | (1.31) | |

| Nonbusiness bankruptcy filings | −18.9788 | −21.9351 | 0.0008 |

| in prior year | (−2.89) | (−2.88) | (0.34) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | 255.1966 | 250.6575 | 0.1855 |

| of lenders | (2.03) | (1.67) | (2.1) |

| Unemployment rate in the current year | 30.3064 | 39.0906 | 0.0022 |

| (2.7) | (2.81) | (0.98) | |

| Percent age 15–29 | 0.0266 | –0.5712 | –0.0012 |

| (0.02) | (−0.29) | (−2.43) | |

| Percent age 30–54 | −2.2204 | −3.2796 | −0.0022 |

| (−1.02) | (−1.27) | (−2.89) | |

| Percent age 55 or more | −5.2354 | −6.8723 | 0.0028 |

| (−1.74) | (−1.96) | (3.77) | |

| Percent age 65 or more | 4.6680 | 5.5625 | −0.0049 |

| (1.42) | (1.49) | (−5.11) | |

| Percent female | 0.5609 | 0.3460 | 0.0009 |

| (0.21) | (0.11) | (1.13) | |

| Percent African American | 0.0437 | −0.0995 | 0.0009 |

| (0.09) | (−0.16) | (4.85) | |

| Percent Hispanic | −1.8796 | −2.6311 | 0.0010 |

| (−2.09) | (−2.21) | (3.75) | |

| Percent some high school | 4.4655 | 5.5167 | 0.0022 |

| (1.42) | (1.49) | (2.86) | |

| Percent high school graduates | 0.3267 | 0.1436 | 0.0019 |

| (0.25) | (0.09) | (5.65) | |

| Percent some college | −1.8102 | −2.5954 | 0.0008 |

| (−1.53) | (−1.85) | (1.77) | |

| Average income (in 1,000 dollars) | 0.5406 | 0.3408 | 0.0002 |

| (1.54) | (0.89) | (2.29) | |

| Average house value | 0.2665 | 0.2797 | −0.0001 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (3.69) | (3.37) | (−3.47) |

| Median rent | 0.0054 | 0.0053 | 0.0000 |

| (0.38) | (0.33) | (0.62) | |

| Tract income relative to MSA | −0.8389 | 0.8504 | −0.0011 |

| (−4.62) | (−4.39) | (−0.18) | |

| Percent unemployed | −3.9790 | −4.7533 | 0.0026 |

| (−2.44) | (−2.39) | (0.05) | |

| Population density (pop./sq. | 0.0017 | 0.0025 | 0.0000 |

| mi. land area) | (1.91) | (1.97) | (−0.14) |

| African American | −45.3060 | −63.4401 | 0.1076 |

| (−3.16) | (−3.51) | (12.85) | |

| Hispanic | 50.8471 | 83.0121 | 0.0612 |

| (0.62) | (0.79) | (4.33) | |

| Female | 107.8836 | 127.7841 | 0.0251 |

| (4.23) | (4.17) | (6.36) | |

| Co-applicant | 3.0911 | 5.5378 | –0.0812 |

| (0.28) | (0.44) | (–26.58) | |

| Income (in 1,000 dollars) | 1.1499 | 1.1869 | –0.0001 |

| (5.25) | (4.74) | (–1.54) | |

| Loan amount/income ≥ 3 | – | – | –0.0003 |

| – | – | (–0.64) | |

| Urban area fixed effects | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| Time fixed effects | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| R2 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.09 |

| Observations | 62,811 | 53,477 | 62,811 |

Note

- The empirical specification is as follows:

- where dependent variable Y is the size of the loan requested for the loan demand regression, or the equilibrium loan size for the loan origination regression, or the probability of the loan being denied for the loan denial regression. U is one if the applicant lives in a state with unlimited homestead exemption, E is the finite homestead exemption, E2 is the quadratic term of the finite homestead exemption,

is the urban area fixed-effects,

is the urban area fixed-effects,  is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on nonconforming-sized home purchase loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on nonconforming-sized home purchase loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

| Size of Loan | Size of Loan | Whether Loan Has | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requested | Originated | Been Denied | |

| Unlimited homestead exemption | −32.3416 | −28.7447 | −0.0481 |

| (−1.85) | (−1.20) | (−3.99) | |

| Homestead exemption level | −0.1312 | −0.0812 | −0.0002 |

| (in 1,000 dollars)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (−1.70) | (−0.86) | (−3.31) |

| Homestead exemption level | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 5.93E-07 |

| squared (in 1,000,000 dollars)*(1-unlimited homestead exemption) | (1.14) | (0.72) | (5.06) |

| Foreclosure must go through | 11.3377 | 1.2829 | 0.0150 |

| the courts | (1.01) | (0.09) | (1.10) |

| Deficiency judgment allowed | 49.8981 | 58.3537 | –0.0029 |

| (2.05) | (1.89) | (–0.15) | |

| Nonbusiness bankruptcy filing | −13.7240 | −15.5269 | −0.0002 |

| in prior year | (−3.43) | (−2.89) | (−0.07) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | −30.3786 | −119.2625 | 0.2231 |

| of lenders | (−0.36) | (−0.96) | (2.26) |

| Unemployment rate in the | 7.0148 | 7.8515 | 0.0070 |

| current year | (1.20) | (0.95) | (3.04) |

| Percent age 15–29 | 2.3558 | 2.4305 | –0.0002 |

| (2.75) | (2.27) | (–0.33) | |

| Percent age 30–54 | 0.7947 | 0.0949 | –0.0026 |

| (0.61) | (0.06) | (–3.05) | |

| Percent age 55 or more | 1.6579 | 1.6668 | 0.0007 |

| (0.92) | (0.78) | (0.81) | |

| Percent age 65 or more | −79.5339 | −145.7699 | −0.3441 |

| (−0.34) | (−0.58) | (−3.33) | |

| Percent female | 3.0935 | 4.6838 | 0.0014 |

| (1.54) | (1.73) | (1.56) | |

| Percent African American | −0.2222 | −0.1343 | 0.0007 |

| (−1.24) | (−0.47) | (3.89) | |

| Percent Hispanic | 0.2501 | 0.1014 | 0.0010 |

| (0.86) | (0.28) | (3.48) | |

| Percent some high school | 1.7121 | 2.6514 | 0.0021 |

| (1.62) | (1.79) | (2.86) | |

| Percent high school graduates | −0.6539 | −1.4022 | 0.0035 |

| (−0.74) | (−1.16) | (9.74) | |

| Percent some college | 1.7392 | 1.5375 | 0.0023 |

| (2.52) | (1.77) | (4.26) | |

| Average income | 0.3757 | 0.2733 | −0.0001 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (1.82) | (1.14) | (−0.59) |

| Average house value | 0.1887 | 0.1389 | −0.0001 |

| (in 1,000 dollars) | (3.67) | (2.36) | (−5.72) |

| Median rent | −0.0162 | −0.0191 | 1.30E-05 |

| (−1.41) | (−1.33) | (2.39) | |

| Tract income relative to MSA | −0.3061 | −0.3166 | 0.0002 |

| (−2.91) | (−2.67) | (3.61) | |

| Percent unemployed | −1.9752 | −2.5291 | −0.0677 |

| (−2.19) | (−2.30) | (−1.66) | |

| Population density (pop./sq. | −0.0008 | −0.0011 | −9.40E−07 |

| mi. land area) | (−1.40) | (−1.48) | (−3.25) |

| African American | −15.6442 | −23.0976 | 0.0742 |

| (−1.90) | (−1.69) | (8.69) | |

| Hispanic | 1.3074 | −4.8994 | 0.0544 |

| (0.21) | (−0.59) | (4.05) | |

| Female | 73.6925 | 103.1267 | 0.0254 |

| (3.87) | (3.86) | (6.56) | |

| Co-applicant | −9.0864 | 2.1079 | −0.0883 |

| (−1.24) | (0.21) | (−28.53) | |

| Income (in 1,000 dollars) | 0.9347 | 1.0007 | −2.96E−05 |

| (8.41) | (7.37) | (−4.40) | |

| Median size of the | 0.0716 | 0.0839 | –7.20E-07 |

| nonconforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract | (1.77) | (1.54) | (–0.30) |

| Loan amount/income ≥ 3 | – | – | 0.1027 |

| – | – | (32.30) | |

| Urban area fixed effects | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| Time fixed effects | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| R2 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.14 |

| Observations | 93,721 | 69,766 | 93,721 |

Note

- The empirical specification is as follows:

- where dependent variable Y is the size of the loan requested for the loan demand regression, or the equilibrium loan size for the loan origination regression, or the probability of the loan being denied for the loan denial regression. U is one if the applicant lives in a state with unlimited homestead exemption, E is the finite homestead exemption, E2 is the quadratic term of the finite homestead exemption,

is the urban area fixed-effects,

is the urban area fixed-effects,  is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on nonconforming-sized refinance loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

is the time-fixed effects, and X is a set of other relevant variables. The regressions are based on nonconforming-sized refinance loans. The sample period is from 2001 to 2008. The t-statistics based on standard errors clustered at the census-tract level are in parentheses.

Conforming-Sized Home Purchase Loans

Loan requested regression

Estimates from the conforming-sized home purchase loan regression suggest that the pattern between the size of the loan requested and homestead exemption is nonlinear and hump-shaped. The curve plotting the pattern is presented in Figure 4. The plot shows that the size of the loan requested increases initially, reaches a peak with a homestead exemption at $262,000 and then declines until it reaches an asymptote when the marginal effect of homestead exemption has no effect on the size of the loan requested. When the homestead exemption is less than $262,000, the house value effect dominates the LTV effect; when the homestead exemption is greater than $262,000, the LTV effect dominates the house value effect. The size of the loan requested in a state with unlimited homestead exemption is $3,196 greater than that of a zero homestead exemption.

The table also contains estimates and t-ratios of other parameters in the model. The coefficient suggests that the size of loan requested is $8,174 smaller in judicial foreclosure states. This result is inconsistent with the prediction that borrowers may respond to the protection imbedded in judicial foreclosure law by demanding larger mortgages in Pence (2006). However, the article does

not test the effect of judicial foreclosure on mortgage demand directly.34 The smaller size of the loan requested may reflect the effect of foreclosure law on the value of the house that borrowers are willing to purchase. It is possible that if borrowers have difficulty obtaining financing in a judicial foreclosure states, they may not be willing to pay as much for a house and they may instead buy a smaller house. The coefficient also indicates that the size of the loan requested is $4,587 greater in states that allow deficiency judgment but not significant. This is consistent with the argument in Pence (2006) that deficiency judgment is not often pursued in practice.

The size of loan requested increases by $800 if the maximum state income tax increases by 0.01. The explanation is that the higher the income tax, the greater incentives for borrowers to take advantage of the mortgage interest deduction and demand a larger mortgage. The estimate of HHI also yields the expected result: a 0.01 decrease in HHI would result in a $501 increase in loan requested. The county unemployment rate has the expected negative effects on the size of loan requested. The application and census-tract variables generally follow sensible patterns. For example, size of the loan requested increases with average house value in the tract.

Loan originated regression

Column (3) in Table 3 provides the evidence of the effect of homestead exemption on the size of the loan originated. In general, the pattern is similar to that of the loan application but provides different point estimates. The plot shows that the size of the loan originated starts to increase initially, reaches a peak with a homestead exemption at $252,000 and then starts to decrease until it reaches an asymptote when the marginal effect of homestead exemption has no effect on the size of the loan originated. The size of the loan originated in a state with unlimited homestead exemption is $2,568 greater than that of a zero homestead exemption. The differences between the coefficient estimates of the two regressions provide evidence of credit constrained, because the size of the loan that is approved is smaller than the size of the loan requested compared to that of a zero homestead exemption state.

The table also contains the estimates and t-ratios of other parameters in the model. The coefficient suggests that equilibrium loan size is about $8,976 smaller in states with judicial foreclosure requirement. This result is consistent with the results in Pence (2006). The greater magnitude than in the previous regression indicates lenders may respond to higher costs by reducing mortgage supply. The coefficient also suggests that equilibrium loan size is about $4,614 greater in states if deficiency judgment is allowed. This result is also consistent with the results in Pence (2006) even though not very significant. The greater magnitude than in the previous regression indicates lenders may respond to potential protection associated with deficiency judgment by increasing mortgage supply.

The size of loan increases by $783 if the maximum state income tax increases by 0.01, which indicates that the mortgage supply side might respond to the income tax change less than the mortgage demand side. A 0.01 decrease in HHI would result in a $446 increase in loan originated, smaller than in the previous regression. Therefore, it may indicate that mortgage borrowers cannot accommodate an increased mortgage demand fully even in a competitive market environment. The county unemployment rate has the expected negative effects on the size of loan requested. The application and census-tract variables generally follow similar sensible patterns as above.

Loan denial regression

Column (4) in Table 3 provides the evidence of the effect of homestead exemption on the probability of loan denial. Even though coefficients of the finite homestead exemption are not significant, it is evident that the mortgage application is 2.06% less likely to be denied in a state with unlimited homestead exemption than in a state with zero homestead exemption. Recall that a mortgage application is denied if the mortgage borrower requests a larger loan than the mortgage lender is willing to extend. Suppose that there is credit constrained even without the impact of the homestead exemption. This result indicates that the difference between borrowers’ preferred level of debt and the debt ceiling imposed by lenders reduces. In that regard, it is also suggestive that mortgage lenders are willing to issue more mortgage credit in a state with a more generous homestead exemption. This highlights the tradeoff of mortgage lenders during the underwriting process caused by state bankruptcy provisions and indicates that the benefits of the “wealth effect” outweigh the costs of foreclosure delay for mortgage lenders. This also sheds some light on the discrepancy in the previous literature. Despite the increase in the size of the loan that mortgage lenders are willing to issue, credit constraint still exists.

The table also contains the estimates and t-ratios of other parameters in the model. The coefficient suggests that the loan is less likely to be denied in states with judicial foreclosure requirement but not significant. This result is inconsistent with the prediction that borrowers may respond to the protection imbedded in this law by demanding larger mortgages and lenders may respond to higher costs by reducing mortgage supply in Pence (2006). However, as it is mentioned earlier, it is possible that if borrowers have difficulty obtaining financing in a judicial foreclosure state, they may not be willing to pay as much for a house and they may instead buy a smaller house and take out a smaller loan. The coefficient also indicates that the loan is less likely to be denied in states that allow deficiency judgment. This is consistent with the idea that deficiency judgment provision provides some protection for mortgage lenders.

The estimate of HHI indicates that the lower HHI, the more competitive the market is and the more likely the loan is denied. The application and census-tract variables generally follow patterns. For example, the loan is more likely to be denied if the applicant is African American or Hispanic and the loan is less likely to be denied if the applicant has a co-applicant.

Conforming-Sized Refinance Loans

Loan requested regression

Consider now the estimates in Table 4 for refinance loan regression to test the LTV effect holding house value constant. Focus first on the regression of the size of the refinance loan requested. Estimates show that holding house value constant, the size of the refinance loan requested in a state with unlimited homestead exemption is $3,246 less than that of a zero homestead exemption. In other words, homeowners in states with a zero homestead exemption may borrow more against their home and decrease the amount of their home equities to protect their homes from been seized and sold.

The table also contains the estimates and t-ratios of other parameters in the model. The variables follow similar patterns as the home purchase loans. One variable stands out in Table 4 that is worth highlighting. The coefficient of the median size of the conforming-sized home purchase loan originated in the census tract is highly significant. These results reinforce the mechanism of LTV effect in my conceptual framework. It can also be interpreted as the more valuable the home, the larger the equity the homeowner wants to retain in the home, and thereby the more likely to take out a refinance loan to extract wealth from the home equity.

Loan originated regression

Column (3) in Table 4 provides the evidence of the effect of homestead exemption on the size of the refinance loan originated. In general, the pattern is similar to that of the size of the loan requested. If the mortgage lender does not treat home purchase loans and refinance loans differently with regard to the impact of the homestead exemption, then it is expected that mortgage lenders are more willing to issue refinance loans in a state with a more generous homestead exemption. The differences between the coefficient estimates of the two regressions suggest that the decrease in the size of the loan requested by the mortgage borrower is larger than the increase in the size of the loan that the mortgage lender is willing to issue.

Loan denial regression

Also, the results from loan denial regressions suggest that a refinance loan application is less likely to be denied in a state with a more generous homestead exemption. The results are consistent with the implications from the previous two regressions: with a decrease in the size of the loan requested by mortgage borrowers and an increase in the size of the loan that the mortgage lender is willing to issue, the loan is less likely to be credit constrained in a state with a more generous homestead exemption.

Jumbo Home Purchase Loans

Loan requested regression

The same set of exercises is repeated in Table 5 for nonconforming-sized, home purchase loans. Focus first on the regression of the size of the loan requested. Estimates suggest a different pattern from that of the conforming-sized market sectors. The size of the loan requested decreases initially and then reaches a minimum with a homestead exemption equivalent to about $3,000,000. Because none of the finite homestead exemption is as large as this number, it is reasonable to believe that the size of the loan requested keeps declining until it reaches an asymptote at the unlimited homestead exemption. The size of the loan requested in a state with unlimited homestead exemption is $158,000 smaller than that of a zero homestead exemption. This is suggestive that the LTV effect dominates the house value effect no matter how generous is the homestead exemption. This is consistent with the idea that the house value effect might be modest for the jumbo loan sectors.

The table also contains the estimates and t-ratios of other parameters in the model. The variables follow similar patterns as the conforming-sized loans. Two variables stand out in Table 5 that are worth highlighting. First, a 0.01 increase in HHI would result in $2,550 increase in loan requested. This suggests that the less competitive the local mortgage market, the larger the size of the jumbo loan requested, in contrast to the conforming counterparts. This result is different from that in the conforming-sized loan sectors. Second, an increase in the county unemployment rate is associated with an increase in the size of the jumbo loan requested. This result is consistent with the high-risk nature of the jumbo loans.

Loan originated regression

Column (3) in Table 5 provides the evidence of the effect of homestead exemption on the size of the jumbo loan originated. In general, the pattern is similar to that of the size of the loan requested. The differences between the coefficient estimates of the two regressions suggest that credit constraint still exists.

Loan denial regression

Also, the results from loan denial regressions suggest that a refinance loan application is less likely to be denied in a state with an unlimited homestead exemption than in a state with a zero homestead exemption. The results are consistent with the implications from the previous two regressions: with a decrease in the size of the loan requested by mortgage borrowers and possibly an increase in the size of the loan that the mortgage lender is willing to issue,35 the loan is less likely to be credit constrained in a state with a more generous homestead exemption.

Jumbo Refinance Loans

Loan requested regression