News Bias in Financial Journalists’ Social Networks

Accepted by Luzi Hail. I thank the associate editor and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments. For feedback, I thank Nihat Aktas, Yakov Amihud, Bernard Black, Audra Boone, Eric de Bodt, Travers Barclay Child, Lauren Cohen, Lin Willian Cong, Stefano DellaVigna, Olivier Dessaint, Daniel Dorn, Daniel Ferreira, Eliezer Fich, Diego Garcia (discussant), Andrey Golubov, Nandini Gupta, Umit Gurun (discussant), Xing Huang, Oğuzhan Karakaş, Markku Kaustia, Matti Keloharju, Yijun Li, Erik Loualiche (discussant), Tim Loughran (discussant), Song Ma, Ron Masulis, Mario Schabus (discussant), Antoinette Schoar, Frederik Schlingemann, Ishita Sen (discussant), Paul Smeets, Noah Stoffman, Laurence van Lent, Vladimir Vladimirov, Michael Weber, Burcin Yurtoglu, Dexin Zhou (discussant), and participants at the 2020 European Finance Association Meetings, 2018 European Finance Association Doctoral Tutorial, CEIBS Finance and Accounting Symposium, European Economic Association Meetings, Helsinki Finance Summit, Indian School of Business Summer Research Conference, Paris December Finance Meeting, SFS Cavalcade North America, Aalto University, Cambridge Judge Business School, Drexel University, Erasmus University Rotterdam School of Management, ESCP–Europe, Fudan University School of Management, Humboldt University in Berlin, Paris–Dauphine University, University of Padova, University of Strathclyde, and WHU–Otto Beisheim School of Management. A previous version of this paper was titled “Friends in Media.” The author has no conflict of interest to declare. An online appendix to this paper can be downloaded at https://www.chicagobooth.edu/jar-online-supplements.

ABSTRACT

Connected financial journalists—those with working relationships, common school ties, or social media connections to company management—introduce a marked media slant into their news coverage. Using a comprehensive set of newspaper articles covering mergers and acquisition (M&A) transactions from 1997 to 2016, I find that connected journalists use significantly fewer negative words in their coverage of connected acquirers. These journalists are also more likely to quote connected executives and include less accurate language in their reporting. Moreover, they tend to portray other firms in the same network in a less negative light. Journalists’ favoritism bias has implications for both capital market outcomes and their careers. I find that acquirers whose M&As are covered by connected journalists receive significantly higher stock returns on the news article publication date. However, these acquirers’ stock prices reverse in the long term, suggesting market overreaction to news covered by connected journalists. Around M&A transactions, connected articles are correlated with increased bid competition and deal premiums. In terms of future career development, connected journalists are more likely to leave journalism and join their associated industries in the long run. Taken together, the evidence suggests that financial journalists’ personal networks promote news bias that potentially hinders the efficient dissemination of information.

What the blurbs did not mention was that each man was praising the work of a sometime boss. […] [The journalists] have since written positively about Lord Black in their columns, though without mentioning their business dealings.

Jacques Steinberg and Geraldine Fabrikant New York Times, December 22, 2003

1 Introduction

The central role of media in the economy has spurred extensive research into the influence of business press on information dissemination (Bushee et al. [2010], Drake, Guest, and Twedt [2014]). However, relatively little research has contextualized journalists’ news stories and studied the sources of potential bias, that is, how and why financial journalists make their editorial decisions. Echoing this view, Call et al. [2022, p. 3] underscore the importance of understanding the “incentives that motivate financial journalists,” as this helps “provide a more complete picture of the environment from which articles in the financial press emerge.”

I make progress on this front by studying (1) how financial journalists’ social networks influence their stories and (2) the consequences of these networks for both financial market outcomes and journalists’ careers. Journalists’ social networks with companies provide reporters with better access to the corporate management. If the financial media compete via accuracy for the attention of rational investors seeking reliable information, a well-connected journalist could advance by providing more credible reporting. However, as Dyck and Zingales [2003] argue, social networks also create an implicit incentive for journalists to inject biases into stories about a firm. Such biases arise because financial journalists may feel obligated to provide positive coverage in exchange for access.1

I assess these predictions by assembling a comprehensive set of financial articles published in The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times from 1997 to 2016.2 I focus on one type of business news: mergers and acquisitions (M&As). M&A news provides a good testing ground for slant in the business media for three reasons. First, the assessment of synergies in M&As is subject to individual perspectives. Gentzkow and Shapiro [2006] predict more media bias in events in which outcomes (e.g., M&A synergies) are difficult to verify. Second, bidding in M&As comprises a series of observable stages. The granularity of the data enables me to examine both short-term effects of bias, such as stock market reactions, and the bidding process, such as bid prices and deal consummation. Finally, acquisitions are an important corporate governance mechanism. Thus, any effects due to distortions in media stories are of first-order importance for shareholders.

My first set of analyses focuses on media slant in M&A articles written by connected journalists. I examine three types of social ties: educational ties, work relationships, and social media links. Using data obtained from professional network Web sites, I identify the colleges attended by the acquirers’ CEOs and the authors of news articles. This enables me to observe whether, for instance, John Riccitiello, CEO of Electronic Arts, attended the same college as Nick Wingfield, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, who wrote about Electronic Arts's acquisition of Take–Two in 2008. To capture potential working relationships between a firm and a journalist, I examine whether a particular reporter has written multiple exclusive stories about that firm within the 12 past months. This approach follows Solomon [2012] and is based on the idea that journalists who frequently cover a firm are more likely to develop personal ties with its management. Furthermore, I examine social media interactions between journalists and CEOs by checking whether they follow each other on Twitter (Barnidge et al. [2020]).

I find a negative correlation between a journalist's social ties and their use of negative words, as defined by Loughran and McDonald [2011]. Specifically, articles written by journalists who have working relationships or school ties with the companies they cover contain approximately 37% (20%) fewer negative words. Similarly, social media affiliations are associated with 59% less negative slant. These results are obtained in panel regressions in which I pool articles that describe the same M&A event. These regressions control for deal fixed effects, which allow me to compare the slant of coverage of the same event. Essentially, deal fixed effects are equivalent to firm × announcement-date fixed effects, which absorb all invariant firm and M&A characteristics on the announcement date. For example, deal fixed effects account for unobserved deal synergies, thus alleviating the concern that differences in synergies drive the results. Suppose I find that Electronic Arts's bid for Take–Two receives less negative coverage in the Wall Street Journal than in the Financial Times. After controlling for deal fixed effects, the difference in slant is solely identified over Electronic Arts's journalist tie in the Journal (but not in the Financial Times). This result indicates favoritism stemming from journalists’ social networks. Moreover, the effect is economically significant: Using well-documented advertising bias as a benchmark (Gurun and Butler [2012]), I find that the influence of social networks is comparable to that of spending US$200,000 per month on advertising at a national newspaper.

Journalists’ social networks are endogenous. For example, companies with higher information asymmetry may have stronger incentives to connect with financial reporters. To alleviate this endogeneity concern, I use the timing of journalist turnover as an instrumental variable to predict the likelihood of connected coverage. The rationale is as follows: For example, suppose Electronic Arts has access to one connected reporter. Shortly before the company announces its bid, that reporter leaves the Wall Street Journal to become an editor for the New York Times. As a result, the probability that this merger will be covered by the connected reporter becomes virtually zero (the relevance condition). Importantly, the exact timing of journalist turnover is likely exogenous to the M&A they cover (Solomon [2012]; the “exclusion restriction”). With the resulting two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression, I continue to find a favoritism bias in journalists’ social networks.

Ancillary analyses reveal that journalists with corporate ties are also more likely to quote the acquiring CEO in their articles. These connected articles often use more ambiguous language than independent coverage. For example, articles authored by connected reporters contain significantly fewer numerical analyses and approximately 10% more uncertainty or weak modal words. The use of more ambiguous language implies that connected journalists may attempt to obfuscate the true nature of the transaction by adopting an equivocal tone. Moreover, I find that financial journalists who have social ties with an acquirer tend to portray other firms in the acquirer's network (e.g., those with an executive serving on the acquirer's board) less negatively. This evidence is consistent with the argument of Shani and Westphal [2016] that journalists’ attitudes toward a company can spill over to other firms in that company's social network.

I next examine the consequences of network bias in financial journalism. Two potential impacts are worth highlighting: The first pertains to the financial market outcomes, and the second to the long-term career trajectories of journalists.

First, I show that journalists’ social ties relate to stock market reactions and attributes of the M&A bidding process. Articles written by journalists who have social ties to companies are associated with significantly higher abnormal stock returns upon news publication. However, after 40 trading days, the higher returns to connected acquirers eventually converge to levels similar to those of nonconnected firms. The evidence of higher short-term acquirer returns and subsequent price reversals suggests overreaction upon news publication for connected firms, consistent with Tetlock's [2007] argument that low media pessimism lifts market prices followed by a long-term reversion to fundamentals. These findings are consistent the favoritism hypothesis, because they suggest that the less negative tone in connected coverage does not convey value-relevant information that could lead to a persistent change in stock prices (De Bondt and Thaler [1985]).

Despite the price correction, media bias could affect capital allocation during M&As. Dutordoir, Strong, and Sun [2022] show that the M&A announcement return is more salient than the long-term stock price correction. Therefore, if deals with connected media coverage have a higher announcement return, this may create the misperception that these M&As are better. This (short-term) misperception may distort public bid competition and deal consummation (Fich and Xu [2023]).

With this literature as a backdrop, I show that stories written by connected journalists are associated with an increase in bid competition following publication. Moreover, bidders in M&As covered by connected journalists are more likely to raise their bid. Finally, because these deals are associated with higher competition following connected media coverage, bidders in these deals may be less likely to complete the transaction. Consistent with this conjecture, I find that connected coverage relates to higher termination rates in some deals. These findings imply that journalists’ social ties do have an impact on the M&A bidding process.

Finally, I investigate whether social connections relate to journalists’ long-term career choices. There are at least two reasons to expect a relation. First, to the extent that reporting credibility matters for reporters’ performance, connected journalists may be more likely to leave their media outlet because their bias hurts their credibility (Call et al. [2022]). Another alternative is that social connections indicate greater outside opportunities. Therefore, connected journalists may be more likely to move into an industry position, especially one that they are connected to (Stigler [1971]).

My analysis shows that social connections are associated with higher journalist turnover. In comparison to independent journalists, connected journalists are 11% more likely to depart for a nonjournalism job and 17% more likely to be hired by firms in their connected industry. Although I do not attempt to empirically distinguish between reporting credibility and outside opportunities, the evidence suggests that social connections relate to financial journalists’ career choices.

This paper contributes to the literature that examines incentives that motivate financial journalists. A related study is by Call et al. [2022], who rely on surveys to understand financial journalists’ incentives and the influences on their journalistic choices. As these authors note, there is “little direct evidence on the process of financial journalism.” Likewise, Westphal and Deephouse [2010] rely on survey data to investigate how poor corporate performance prompts executives to ingratiate themselves with journalists. Using archival data, my study complements the survey evidence by showing that, in addition to providing accurate news coverage, financial journalists often feel beholden to their connected sources. The bias documented here thus contrasts with prior accounting research that focuses on the information intermediary role of the media.3 My findings also improve our understanding of how companies influence editorial content (Reuter and Zitzewitz [2006], Bushee and Miller [2012], Gurun and Butler [2012], Solomon [2012]).

Second, this study contributes to the literature on social networks by investigating a novel form of social interaction. Miller and Skinner [2015] note that there is an incredible opportunity for researchers to contribute to the understanding of the media's interactions with other financial market players. This study advances this area of research by documenting (1) the direct effect of journalists’ personal networks on media slant, (2) the spillover effect of journalist connections on the coverage of other (second-degree connected) firms, and (3) potential career outcomes shaped by those networks. Because the incentives of financial reporters to spin the news (i.e., access to firm management) differ from those of corporate directors (i.e., enhancing corporate governance), my paper also complements other studies that examine companies’ media directors and executives (Gurun [2020], Hossain and Javakhadze [2020], Ru et al. [2020]).

Finally, this study adds to the growing literature using text as data (Hansen, McMahon, and Prat [2017], Bae, Hung, and van Lent [2023]). My paper contributes by exploring a diverse set of textual attributes, such as verbatim quotes, uncertainty words, and weak modal words, to provide more nuance about how journalists present their reports. By going beyond tone, my research enhances the empirical credibility of some of the key constructs and helps advance the field toward a deeper depiction of financial news reporting.

2 Literature, Institutional Background, and Hypotheses

2.1 BUSINESS MEDIA AS AN INFORMATION INTERMEDIARY AND MEDIA SLANT

Price discovery does not happen instantly (Lee [2001]). Value-relevant information is often disseminated to the capital markets by information intermediaries, such as sell-side analysts and the business media. Research in accounting and finance has established two key roles of financial media. First, they facilitate the dissemination of firms’ news. For example, Kross, Ro, and Schroeder [1990] find that Wall Street Journal coverage improves analysts’ forecasts. Bushee et al. [2010] and Rogers, Skinner, and Zechman [2016] show that media coverage reduces information asymmetry. As a result, journalists’ activities have the potential to directly influence the pricing of information in the stock market (e.g., Tetlock [2007], Fang and Peress [2009], Kothari, Li, and Short [2009], Engelberg and Parsons [2011]).

The second role of media is information creation. Recently, Guest [2021] has shown that the Wall Street Journal’s editorial content provides new information that facilitates investors’ understanding of earnings news. New information also helps investors monitor firms’ managers. For example, Frankel and Li [2004], Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales [2008], Liu and McConnell [2013], and Dai, Parwada, and Zhang [2015] find that the media help discipline managers and enhance corporate governance. Miller [2006] highlights the role of the media as a watchdog for accounting fraud. Core, Guay, and Larcker [2008] reveal that media influence CEO pay. Bushman, Williams, and Wittenberg-Moerman [2016] suggest that media stories affect syndicated loan origination.

Given the importance of the business media, a burgeoning literature investigates news spin. Perhaps most prominently, Reuter and Zitzewitz [2006] and Gurun and Butler [2012] provide evidence that firms use advertising expenditures to influence the tone of financial news coverage. Solomon [2012] shows that investor relations services help firms spin the news. Cagé et al. [2024] document the influence of media owners on media bias. These studies raise questions about the independence of media. More broadly, the journalism literature examines the demand- and supply-side determinants of media bias. For example, Ekstrom et al. [2013] show that journalistic values and interviewee characteristics both relate to interrogation bias. Ameli and Molaei [2020] and Joa and Yun [2022] find that the partisan affiliation of the media is significantly associated with news sentiment. Yamamoto and Nah [2018] suggest that community-level factors, such as social and political trust, contribute to newspaper credibility. Conway-Silva, Ervin, and Kenski [2020] reveal that cable news uses different sourcing patterns to produce biased coverage. This literature primarily focuses on political bias in media coverage. In contrast, my work examines financial media coverage and explores the potential media slant introduced by personal connections between journalists and management of the firms they cover.

2.2 MEDIA COVERAGE DURING M&A NEGOTIATIONS

M&As create large incentives for firms to manage media coverage. Ahern and Sosyura [2014] show that favorable news coverage affects acquirers’ stock prices and deal terms. Hossain and Javakhadze [2020] examine directors who work in media firms. They find that media directors influence takeover premia and announcement returns by improving acquirers’ media coverage before deal announcements.

Although these papers focus on the strategic manipulation of media coverage during M&A negotiations, which can directly affect deal terms, my study focuses on whether journalists’ activities after a deal's announcement (e.g., through analyzing transaction synergies) are related to subsequent M&A outcomes. Analysis of M&A deal synergies provides a good setting for testing media bias because M&A synergies are not directly observable and thus create incentives for news spin (Gentzkow and Shapiro [2006]). Moreover, journalists’ analyses could influence the perception of the deal postannouncement and may influence subsequent deal processes, such as competition and completion, which are important for the shareholders of the transacting parties. Finally, from an identification perspective, focusing on one homogeneous event type (i.e., M&As) provides a clean setting because the tone of news coverage is primarily determined by the underlying story. Combining various events—say, scandals and acquisitions—would make it difficult to control for underlying event characteristics and could lead to biased estimates if these characteristics were correlated with a journalist's connectedness. To assess the external validity of the tests, I extend the analysis to a sample of financial fraud news in section 4.4.

2.3 INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

I focus on two of the most prominent financial newspapers in this study, the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. The Journal has a longstanding reputation as a business newspaper with a primary focus on the U.S. market, whereas the Financial Times is known to have a global focus, covering news from around the world. Both are well established among finance professionals.

In the production of news, editors are primarily responsible for selecting the stories to publish, whereas journalists write and develop assigned stories. Reporters may either be general assignment reporters or specialize in particular industries for business news reporting.4

- H1: Editorial content authored by connected journalists is more informative and, implicitly, exhibits less slant, which leads to more efficient price discovery and quicker assimilation of information into market prices.

However, there are also reasons to expect that journalists introduce bias when they have social ties with the firms they cover. First, financial journalists rely on company management for information, which creates an implicit incentive for favorable bias (Dyck and Zingales [2003]). A survey by Call et al. [2022] finds that private communications with firms constitute a major source of information for financial reporters. Intriguingly, their survey also reveals that journalists often face backlash from firms in response to unfavorable reporting.

Second, due to homophily—the tendency for individuals with similar backgrounds to associate with each other—journalists with ties to corporate executives may share similar preferences and beliefs as those executives. This could lead a journalist and a CEO to both view a corporate decision through the same lens, for instance, as value creating even though it is not. As Uzzi [1996, p. 678] notes, such a social tie “disposes one to interpret favorably another's intentions and actions.”

Finally, a journalist in a firm's network is more likely to have developed personal relationships with the firm's management due to the frequent contact between individuals in the same network (Barrios et al. [2022]). These personal relationships could lead to favoritism in which journalists depict their connections more positively. Meanwhile, due to more positive slant in the connected coverage, investors may respond more favorably to the related information (Tetlock [2007]). This happens because noise or liquidity traders face downward-sloping demand for risky assets (DeLong et al. [1990]) or because investors have limited attention (Barber and Odean [2008]). Importantly, although initial mispricing could occur, the stock price should ultimately be corrected in the long run as markets are expected to see through biased information (De Bondt and Thaler [1985]).

- H2: News articles authored by connected journalists exhibit more favorable slant, leading to a higher stock return upon news announcement (mispricing) and subsequent price reversion.

In the following sections, I examine the empirical question of whether articles written by connected journalists are more accurate or biased.

3 Sample and Data

3.1 SAMPLE OF NEWS ARTICLES

I first collect all of the M&A bids from 1997 to 2016 involving U.S. public firms. These data come from Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum. The sample period begins in 1997 because the main measure of the journalists’ social networks requires a manual search on the Wall Street Journal engine, which starts in 1997. Following the sample selection methods commonly used in the M&A literature (see, e.g., Masulis, Wang, and Xie [2007]), I ensure that (1) the transaction value exceeds US$10 million, (2) the target is not undergoing bankruptcy proceedings, and (3) the parties are nonfinancial firms. These criteria yield 2,390 deals.

Not all M&As are covered by newspapers. I search the media coverage using the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times Web sites and Factiva, a media research tool owned by Dow Jones. To ensure that I am not selecting stories about M&A rumors, I require the news article to be the first report on the transaction following the official deal announcement. Additionally, I focus only on articles that provide author information. This leads me to drop newswire articles.5 Following these selection criteria, I obtain 1,370 articles from the Wall Street Journal and 666 articles from Financial Times, corresponding to 57% and 28% coverage rates, respectively. Among these articles, 651 unique deals are covered by both newspapers, representing an overlap of 1,302 articles (i.e., 651 articles from each outlet). I refer to this panel data set of 1,302 articles as the “pooled sample,” upon which I conduct media slant analysis.

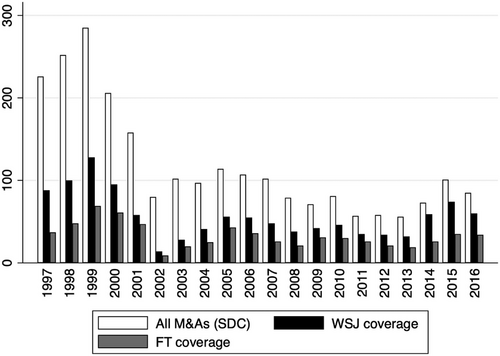

In some of my cross-sectional analyses, such as those of deal announcement returns and deal processes, I require additional information on stock performance and firm characteristics. I obtain firms’ financial data from Compustat and stock data from CRSP. After matching the covered firms with Compustat and CRSP, I am left with 1,131 deals covered by the Wall Street Journal and 650 deals covered by the Financial Times. Figure 1 shows the number of M&A bids across years. The number of bids is lower after the dot-com bubble crash in 2001 and again during the financial crisis in 2008. Overall the Wall Street Journal provides more solid coverage of transactions than the Financial Times: The covered deals in the Journal (Financial Times) collectively account for over US$5.9 trillion (5.1 trillion) in transaction value and have a median size of US$1.5 billion (2.7 billion). This compares to the median SDC deal size of US$0.4 billion. The relatively large transaction value is perhaps unsurprising, as big transactions attract greater media attention. Most of these M&A stories (over 95%) appear within two days following the official press release by the company.

3.2 JOURNALIST-FIRM NETWORKS

Measuring journalists’ social networks is challenging, as individual networks are not directly observable. Therefore, I adopt conventions used in the accounting and finance literatures to construct two proxies: working relationships and educational ties. In addition, I use social media pairs, drawing from the journalism literature, as another proxy for journalist-firm ties. Admittedly, this practice omits other potential social networks, such as second-degree ties. To the extent that these omitted networks matter for media slant, my focus on the work, educational, and social media ties conservatively estimate network effects.

I identify working relationships following the logic of Solomon [2012]. Specifically, I check whether a reporter has written multiple exclusive stories about the same company within the 12 months prior to the merger.6 For example, Betsy McKay, the author who covered PepsiCo's acquisition of Quaker Oats in December 2000, wrote more than 10 stories about PepsiCo in 2000, featuring several interviews with the firm's top executives. It is likely that Betsy had established a working relationship with the firm. My measure of the working relationship, CONNECT_WORK, takes a value of one if any author of the M&A story covered the bidding firm at least twice in the previous year.7 Admittedly, working relationships may be a product of specific journalist skills. Regardless of their cause, I argue that they could influence slant if a social tie is formed. I discuss the related endogeneity issue in the following section.

To construct the educational networks, I search for the universities that the journalists and the CEOs attended. I use a variety of sources. The newspaper Web sites provide personnel biographies of the authors. I supplement this information with data gathered from LinkedIn, a professional networking service. I gather the CEOs’ universities from the companies’ proxy filings on the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC's) EDGAR database and Bloomberg. Finally, if I cannot determine a reporter's or CEO's university with the primary sources, I perform general Web searches to collect additional information. Because the databases do not provide records of graduation years, I cannot systematically observe the school ties within a cohort. Nevertheless, this measure of educational ties is consistent with prior work showing that general alumni networks have significant impacts on financial markets (e.g., Cohen, Frazzini, and Malloy [2008], Ru et al. [2020], Chen et al. [2021]). The measure of educational ties, CONNECT_UNIVERSITY, equals one if any author of the article attended the same school as that attended by the CEO.

Finally, I create a variable, CONNECT_TWITTER, to capture the existence of a CEO-journalist pair on social media (specifically Twitter). The indicator variable equals one if a CEO and a journalist follow each other on Twitter and zero otherwise. Research on journalism suggests that interactions on social media, such as Twitter, can indicate both formal and informal social connections (Barnidge et al. [2020]). These social interactions in turn may influence the (perceived) media bias (de Zuniga, Diehl, and Ardevol-Abreu [2018]).

Table 1 reports the summary statistics of journalist-firm networks. Approximately 27% of articles across the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times are authored by journalists with a working relationship with the firm. This aligns with Li's [2015] remark that business reporters seldom cover the same firm more than once a year. As a comparison, I create a variable, Industry expert, that identifies whether the authors specialize in the relevant industry. Table 1 shows that about 46% of articles are written by reporters who are industry experts. This comparison suggests that repeated coverage goes beyond general expertise and indicates a relationship with the firm. However, social ties via schooling and on Twitter are infrequent. Only 2.3% of journalists have attended the same university as the firm's CEO, and less than 1% of journalist-CEO pairs follow each other on Twitter. Note that this latter statistic is influenced by the fact that many CEOs do not have Twitter accounts.

| Wall Street Journal | Financial Times | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Median | Mean | S.D. | Median | |

| Number of articles by journalists | 1,131 | 650 | ||||

| Journalist/news characteristics | ||||||

| CONNECT_WORK | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0 | 0.286 | 0.452 | 0 |

| CONNECT_UNIVERSITY | 0.023 | 0.150 | 0 | 0.022 | 0.145 | 0 |

| CONNECT_TWITTER | 0.007 | 0.084 | 0 | 0.009 | 0.096 | 0 |

| Negative slant (%) | 1.396 | 0.868 | 1.245 | 1.305 | 0.936 | 1.142 |

| Local journalist | 0.227 | 0.419 | 0 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 |

| Female | 0.441 | 0.497 | 0 | 0.317 | 0.466 | 0 |

| Tenure (months) | 67 | 59 | 51 | 142 | 92 | 118 |

| Industry expert | 0.477 | 0.500 | 0 | 0.455 | 0.498 | 0 |

| Deal event characteristics | ||||||

| Relative deal size | 0.538 | 0.707 | 0.293 | 0.545 | 0.728 | 0.295 |

| Absolute deal size ($billion) | 5.230 | 12.711 | 1.544 | 7.852 | 15.961 | 2.670 |

| Hostile | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0 | 0.037 | 0.189 | 0 |

| Unsolicited | 0.047 | 0.211 | 0 | 0.055 | 0.229 | 0 |

| Cross-industry | 0.324 | 0.468 | 0 | 0.323 | 0.468 | 0 |

| Financing (cash) | 0.473 | 0.439 | 0.450 | 0.459 | 0.432 | 0.416 |

| Toehold (%) | 0.348 | 3.314 | 0 | 0.415 | 3.639 | 0 |

| Firm characteristics: | ||||||

| Firm size (log) | 8.592 | 1.761 | 8.617 | 9.090 | 1.638 | 9.170 |

| Tobin's Q | 2.763 | 2.949 | 1.868 | 2.993 | 3.334 | 1.910 |

| Firm leverage | 0.149 | 0.134 | 0.116 | 0.145 | 0.132 | 0.112 |

| Firm cash | 0.157 | 0.182 | 0.081 | 0.159 | 0.188 | 0.081 |

| Firm profitability | 0.043 | 0.119 | 0.052 | 0.049 | 0.110 | 0.054 |

| Institutional ownership | 0.621 | 0.256 | 0.667 | 0.612 | 0.250 | 0.655 |

| # Analysts | 15 | 10 | 14 | 17 | 11 | 17 |

| CEO age | 54 | 7 | 54 | 55 | 7 | 55 |

| CEO duality | 0.656 | 0.475 | 1 | 0.692 | 0.462 | 1 |

| Classified board | 0.447 | 0.497 | 0 | 0.405 | 0.491 | 0 |

- This table reports the summary statistics for journalist, deal, and firm characteristics. CONNECT is a dummy variable that indicates the article is written by a connected reporter. Negative slant is the proportion (%) of negative words in an article. Local journalist (dummy) indicates that the journalist is based in the same city as the firm headquarter. Female (dummy) indicates female journalists. Tenure is the months of work experience. Industry expert (dummy) indicates journalists reporting in the firm's industry. Relative deal size is deal value scaled by the bidder's market value four days before the announcement. Hostile and Unsolicited are dummy variables for hostile and unsolicited bids. Cross-industry (dummy) flags bids for target firms unrelated to the bidder's (Fama-French 48) industry. Financing is the proportion of the transaction paid in cash. Toehold is the stake owned by the bidder prior to the bid. Firm size is the logarithm of book value of total assets. Tobin's Q is market value of assets over book value of assets. Leverage is book value of debts over market value of assets. Cash is cash holdings scaled by total assets. Profitability is the net income scaled by total assets. Institutional ownership is the stake of the bidder firm owned by financial institutions. # Analysts is the number of analysts following the bidder prior to the bid. CEO duality and Classified board are dummy variables that flag a CEO who is also the chairman of the board and a staggered board, respectively. Detailed definitions of all variables are reported in online appendix 1.

Although a social tie from the same alma mater is arguably exogenous to the concurrent economic fundamentals of a corporate event, social ties based on working relationships or social media are not. To account for journalists’ experience and personal traits, I construct several variables, namely, Local journalist, Tenure, Industry expert, and Female, to control for the general influence of journalist characteristics. These variables are described in online appendix 1. Furthermore, online appendix table A1 reports the correlations between journalist-firm ties and journalist characteristics. We see that a working relationship is positively correlated with a journalist being local or an industry expert. However, the variable CONNECT_UNIVERSITY is uncorrelated with other journalist traits or event characteristics, suggesting that a schooling tie formed years ago is likely exogenous to a firm's current performance.

3.3 MEDIA SLANT

The average negativity expressed in an M&A article equals 1.3%−1.4% (see table 1). This compares favorably to the 1.7% negative slant reported by Gurun and Butler [2012]. To provide a sense of the slant, online appendix 2 offers several examples of articles (excerpts). I obtain similar results using a measure of net slant, namely, the fraction of negative words minus positive words, in the robustness tests.

3.4 DEAL AND FIRM CHARACTERISTICS

I construct several firm and deal characteristics as control variables. These characteristics are motivated by the M&A literature and have been widely used to capture merger qualities (e.g., Cai and Sevilir [2012], Kim, Verdi, and Yost [2020]). For example, I collect the deal's relative size, hostile attitudes, nonsolicitations, cross-industry bids, payment methods, and toeholds from SDC. From Compustat, I gather information about firm size, Tobin's Q, leverage, cash holdings, and profitability. Institutional ownership data come from Thomson/Refinitiv. Analyst coverage comes from the Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System. Additionally, I obtain CEO- and board-related variables—including CEO age, duality, and classified board—from the firms’ proxy filings in EDGAR.9 Online appendix 1 reports the definitions of all variables. Table 1 provides the summary statistics.

3.5 ENDOGENEITY OF MEDIA COVERAGE

I start by discussing the concern that a sample selection bias exists. Specifically, it would be worrisome if news coverage were correlated with reporters’ social networks. To investigate this possibility, I use a probit estimator to predict media coverage using the full list of M&A bids.10 The analysis reveals that journalists’ social networks do not have a significant impact on news coverage. Instead coverage is primarily driven by firm and deal size as well as by sensational aspects, such as hostile and unsolicited transactions. This evidence is consistent with the argument that individual reporters do not control which stories are ultimately published.

4 Journalist Ties and Media Slant

4.1 EMPIRICAL STRATEGY AND MAIN RESULTS

The main variable of interest, CONNECT, corresponds to one of the three measures of journalist-firm ties described in section 3. To test whether ties relate to slant, I estimate whether β differs statistically from zero. Equation (2) includes deal fixed effects (Di), which allow me to benchmark slant across media while holding the information content of the event constant. Because deal fixed effects subsume all deal-level estimates, the regression does not control for any (time-varying or invariant) deal and firm characteristics.11 As a result, the only controls I include are journalist characteristics, Zij. Here, Z includes a dummy variable indicating whether the journalist is in the same city as the firm's headquarters, the journalist's gender, tenure, and industry expertise. I use media fixed effects (Mm) to control for the general writing style of the media outlet. Alternatively, I include journalist fixed effects (Jj), which control for a journalist's general slant. Standard errors are clustered by event (i.e., a deal) to account for the possibility that media slant or news sentiment may be correlated within an M&A event.12 In this pooled sample, each M&A event is covered by two articles. The mean percentage of articles written by journalists with a working relationship, university tie, or social media connection is 27%, 2%, and 0.8%, respectively.

Panel A of table 2 reports the results. Across the columns, the coefficients on CONNECT are all negative and statistically significant. The negative point estimates suggest less negative coverage in connected publications. Based on the estimates with deal and media outlet fixed effects (see the odd-numbered columns), an article authored by a journalist with a working relationship contains 36.7% fewer negative words, relative to an independent article on the same event. In the case of a school or social media connection, the use of negative words is 19.8% and 58.9% lower, respectively.13 Because school ties and social media connections are rare, I refrain from drawing strong inferences from these estimates. However, these results support the evidence derived from the working relationship, suggesting that connections are associated with less negative coverage.

| Panel A: Pooled OLS regressions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable = Negative Slant | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| CONNECT_WORK | −0.514*** | −0.553*** | ||||

| (0.067) | (0.096) | |||||

| CONNECT_UNIVERSITY | −0.277* | −0.477** | ||||

| (0.161) | (0.203) | |||||

| CONNECT_TWITTER | −0.825*** | −0.726* | ||||

| (0.310) | (0.424) | |||||

| Local journalist | 0.013 | −0.047 | −0.029 | −0.115 | −0.020 | −0.139 |

| (0.091) | (0.148) | (0.100) | (0.154) | (0.099) | (0.151) | |

| Female | −0.082 | −0.064 | −0.109* | −0.128 | −0.119** | −0.102 |

| (0.055) | (0.158) | (0.058) | (0.163) | (0.058) | (0.162) | |

| Tenure | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.001 |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Industry expert | 0.038 | −0.132 | −0.006 | −0.180 | −0.015 | −0.185* |

| (0.059) | (0.110) | (0.061) | (0.110) | (0.060) | (0.110) | |

| Constant | 1.549*** | 1.646*** | 1.461*** | 1.629*** | 1.462*** | 1.605*** |

| (0.053) | (0.175) | (0.056) | (0.179) | (0.055) | (0.180) | |

| Deal FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Journalist FE | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 1,302 | 880 | 1,302 | 880 | 1,302 | 880 |

| R2 | 0.683 | 0.840 | 0.659 | 0.827 | 0.663 | 0.827 |

| Panel B: Two-stage least squares regressions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Stage: CONNECT | Second Stage: Negative Slant | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Turnover (promotion) | −1.135*** | −0.933*** | ||

| (0.071) | (0.102) | |||

| CONNECT_WORK | −0.189** | −0.323** | ||

| (0.077) | (0.143) | |||

| Controls (as in panel A) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Deal FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 320 | 320 | 320 | 320 |

| R2 | 0.488 | 0.513 | 0.255 | 0.306 |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F | 254.970 | 83.834 | ||

- The table shows the relation between journalist ties and media slant. The sample in panel A includes all overlapping articles that cover the same M&A event from the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. Panel B uses a subsample of that in panel A, where firms are covered at least twice and have at least one journalist tie. Panel A reports OLS regressions where the dependent variable is Negative slant, measured as the fraction of negative words in the text of a news article. Higher values indicate more negative slant. Panel B reports two-stage least squares regressions where CONNECT_WORK is instrumented with connected journalists’ turnovers. In the first stage (columns 1 and 2), CONNECT_WORK is instrumented by the connected journalist Turnover, a dummy variable that indicates cases in which a bidding firm's connected journalist leaves the media outlet and moves to a higher position in another outlet during the six-month window before the M&A announcement. In the second stage (columns 3 and 4), Negative slant is regressed on the instrumented CONNECT_WORK. Journalist-level control variables (same as those in panel A) as well as average journalist slant is included in all regressions. Definitions of control variables appear in online appendix 1. Deal, media outlet, and/or journalist fixed effects are indicated at the bottom of the table. Standard errors are clustered by event (deal) and reported in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Since media sentiment is influenced by the interplay between companies and journalists, I also estimate a model that includes more saturated journalist fixed effects (see the even-numbered columns). This model essentially compares journalists’ tone in excess of their usual tone. It addresses the concern that journalists with more corporate ties might be generally more optimistic. The results remain consistent with previous findings.

Call et al. [2022] indicate that financial journalists often rely on company disclosures when crafting their stories. Therefore, as another way of comparing slant, I benchmark the language in the newspapers to that of the press release issued by the bidding companies. These results are reported in table A3 of the online appendix. The results continue to show a network bias that favors the firm. Here, the economic effects are that corporate ties through a working relationship or a school or social media tie are associated with 22.1%, 23.9%, and 47.4% less negativity relative to firm-initiated press releases, respectively.

To get a sense of magnitudes, I compare these results to the well-documented advertising bias: Gurun and Butler [2012] show that spending US$200,000 per month on advertising in a national newspaper is associated with a 36% increase in slant measured in the same way as my study. Thus, the impacts of social networks appear to be similar in magnitude, if not larger, than the impact of advertising bias at the US$200,000-per-month level.

With respect to the control variables, there is little evidence that expertise, as captured by Tenure and Industry expert, is systematically associated with slant. This is perhaps unsurprising because the estimates are conditional on the information content of the event.

4.2 INSTRUMENTING JOURNALIST TIES

Despite the use of various fixed effects in table 2, panel A, endogeneity concerns remain. The primary concern is the possibility of reverse causality. For example, executives might have stronger incentives to connect with journalists if their company's information asymmetry is high. Alternatively, if the firm's information environment is poor, journalists may feel that they can make more of an impact by developing relationships with the company's executives and by providing favorable (i.e., less negative) press coverage.

To address this concern, I propose an instrumental variable that is correlated with the probability of connected coverage but has no independent effect on slant. I contend that journalists’ turnover timing (i.e., the specific time at which they leave the media outlet) satisfies both the relevance condition and the exclusion restriction. The rationale is as follows: The departure of a friendly reporter today will decrease the likelihood of the firm being covered by a connected journalist in the future. However, the exact timing of turnover (say, one month before a merger announcement) is unlikely to be determined by the covered firms and is thus exogenous (Solomon [2012]).

Two issues may confound the plausibility of using turnover timing as an instrumental variable. First, one may worry that, even in the presence of turnover, editors might assign other connected reporters as a replacement (thus violating the relevance condition). To alleviate this concern, I focus solely on cases where a firm is connected to one reporter prior to the M&A.14

Another concern is that journalist turnovers could be driven by their past slant and thus would not be exogenous. To mitigate this concern, I manually search to identify the reasons behind each turnover and only include cases where a reporter leaves to take on a more senior role, such as editor, at another media outlet. If a journalist is promoted to a higher position, this is not a turnover triggered by abnormal slant in the journalist's reporting (Call et al. [2022]). Conversely, if a journalist leaves due to inaccurate reporting (slant), it is more likely that that person has been demoted or has quit journalism. In my analysis, I focus on the timing of promotions that occur in the six months leading up to an M&A announcement. If a firm's sole connected journalist turns over during this period, I set the dummy variable Turnover (promotion) equal to one. Although testing for the exclusion restriction is inherently infeasible, I perform untabulated tests and find that (1) firm performance is uncorrelated with the connected journalists’ turnover and (2) the average slant in the journalists’ past publications is not associated with Turnover (promotion).

To construct the sample of turnovers, I consider the following criteria: First, given that a firm's connectedness is endogenous, it would not be logical to compare firms with zero journalist ties to those with ties. Therefore, I focus on firms that have at least one journalist tie so that the firms are more comparable. Second, because promotion timing generates exogenous variation of journalist ties in a time series, the exercise is possible only for firms that have conducted more than one transaction (see online appendix 3 for a description). These restrictions result in a reduction of observations. Therefore, I perform this analysis only with the connectedness measure of working relationships. Using the new sampling criteria, I obtain 320 articles from both newspapers covering the same event, with 248 authored by connected journalists. In total, I observe 10 turnover events preceding the M&A announcement.15

Panel B of table 2 reports the 2SLS results. Similar to the preceding OLS analysis, the regression relies on a pooled data set with deal fixed effects. The first-stage results, presented in columns 1 and 2, indicate that a recent turnover of a connected journalist significantly reduces the likelihood of a future report being written by a connected reporter in the firms’ network. The F-statistic on the instrument is above the critical values proposed by Stock-Yogo, suggesting that the estimation is efficient.

Columns 3 and 4 report the estimate of the second-stage regression. The network effect is highly statistically significant, pointing in the same direction of slant as that documented in panel A of table 2. The Sargan χ2 test cannot reject the joint null that the instrument is valid. The magnitude of the slant is close to the corresponding OLS estimate reported in panel A. This suggests that the estimates are likely to be accurate.16

Jiang [2017] notes that, in an instrumental variable test, the average treatment effect is local, which inhibits generalizing the findings to a larger population. I acknowledge that the local effect in this smaller sample is the cost of achieving greater internal validity. To the extent that my purpose is to detect a network bias, rather than quantify the slant, this exercise still offers valuable insight into the plausibility of the underlying hypothesis. However, when interpreting the results, one should be cautious about underlying assumptions, such as the exclusion restriction.

4.3 ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE: QUOTES OF CEOs, ACCURACY, AND SPILLOVER EFFECTS

In this section, I provide additional evidence supporting the effect of social ties between journalists and firms. These tests examine (1) verbatim quotes of connected CEOs, (2) alternative textual features in news stories, and (3) spillover effects on a CEO's social network of firms.

I first assess the extent to which the mergers are ascribed to specific individuals, such as the acquiring CEO. The rationale for this test is that, in addition to the generally favorable coverage of an M&A deal, a reporter with social ties may be particularly friendly to a senior executive of the firm. In the first three columns of panel A of table 3, I study this conjecture. The dependent variable is the number of quotes of the CEO in a news article. The regression specification is otherwise similar to that in equation (2).

| Panel A: Quotes of CEOs and accuracy of news analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Quotes of CEOs | Use of numbers (%) | ||||

| Type of Network | Work | University | Work | University | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| CONNECT | 0.145** | 0.384*** | 0.697* | −0.005** | −0.001 | −0.025* |

| (0.067) | (0.105) | (0.418) | (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.015) | |

| Controls (as in table 2) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Deal FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 |

| R2 | 0.612 | 0.612 | 0.615 | 0.581 | 0.578 | 0.584 |

| Dependent Variable | Use of uncertainty words (%) | Use of weak modal words (%) | ||||

| Type of network | Work | University | Work | University | ||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| CONNECT | 0.111* | −0.032 | 0.367** | 0.101** | −0.080 | 0.245** |

| (0.060) | (0.125) | (0.159) | (0.047) | (0.123) | (0.095) | |

| Controls (as in table 2) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Deal FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 | 1,302 |

| R2 | 0.550 | 0.547 | 0.549 | 0.579 | 0.575 | 0.576 |

| Panel B: Spillover effect | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Negative Slant | |

| 1 | 2 | |

| CONNECT_Indirect | −0.393** | −0.327** |

| (0.169) | (0.165) | |

| CONNECT_Direct | −0.426*** | |

| (0.059) | ||

| Controls (as in table 2) | Yes | Yes |

| Firm × Year-month FE | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet FE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 6,988 | 6,988 |

| R2 | 0.439 | 0.446 |

| Panel C: Articles on financial fraud | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Negative Slant | |

| Type of Network | Work | University |

| 1 | 2 | |

| CONNECT | −0.786*** | −1.065** |

| (0.222) | (0.455) | |

| Controls (as in table 2 + firm characteristics) | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Media outlet fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 378 | 378 |

| R2 | 0.372 | 0.369 |

- The table shows additional evidence of journalist network effects. Panel A uses the same sample as that used in table 2. Panel B examines the negative slant in news coverage of companies whose executives are sitting on the board of the M&A acquiring firm; in this sample, news coverage of other major business events is included. Panel C probes the external validity using an overlapping sample of news articles on corporate financial fraud from the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. Fraud events are collected from SEC's Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases from 1997 to 2016. In panel A, columns 1−3 examine whether connected journalists are more likely to quote the CEO of the firm. The dependent variable is the number of quotes of CEO in the article. Columns 4−12 examine the accuracy of the report. In columns 4−6, the dependent variable is the percentage of numerical analysis (numbers) in the article. In columns 7−9, the dependent variable is the percentage of uncertainty words in the article. In columns 10−12, the dependent variable is the percentage of weak modal words in the article. Panel B examines spillover effects of journalist ties. The main independent variable is CONNECT_Indirect, an indicator variable that equals one if (at least one) journalist has a second-degree connection to the company whose executive is also a director in the M&A acquirer firm and the journalist is connected to the M&A firm via a working relationship, university tie, or Twitter tie. The variable CONNECT_Direct is an indicator variable for direct journalist ties to the covered firm via a working relationship, university tie, or Twitter connection. Definitions of all variables appear in online appendix 1. Fixed effects are indicated at the bottom of each table. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by event (deal) in panel A, by firm-year-month in panel B, and by fraud event in panel C. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

The results show that connected journalists are indeed more likely to directly quote the acquiring CEO. For example, an article authored by a journalist with a working relationship with the firm contains 15% more CEO's verbatim quotes than other articles covering the same deal. Likewise, a journalist who attended the same university as the CEO cites 38% more of the CEO's quotes. These findings reveal a novel strategy in which connected journalists attribute deal qualities to specific corporate executives.

I next examine the textual characteristics of news reports that pertain to accuracy. Note that a less negative tone does not necessarily imply that the news content is inaccurate. Under the information transmission hypothesis, connected journalists with access to private information should provide more accurate statements in their analyses. However, under the favoritism hypothesis, journalists within a firm's social network may attempt to obfuscate the true nature of the transaction by using a less negative but more ambiguous or equivocal tone. To achieve this, they may avoid using precise numerical analyses and instead rely on ambiguous language, such as uncertainty words and weak modal words (Kim [2018]). In columns 4−12 of panel A of table 3, I use three different dependent variables that capture the accuracy (or ambiguity) of a news article, namely, the percentage of numerical predictions, the percentage of uncertainty words, and the percentage of weak modal words.17 These regressions are specified based on equation (2).

The results suggest that journalists with a working relationship or a Twitter tie with the CEO use fewer numerical analyses in their reports than independent journalists. They also use significantly more ambiguous language in their writing. Specifically, CONNECT_WORK (TWITTER) is associated with a 1% (3%) decrease in numerical analyses, an 11% (37%) increase in uncertainty words, and a 10% (25%) increase in weak modal words. However, the effect of university ties is statistically insignificant. These findings provide suggestive evidence that journalist ties are related to a less accurate portrayal of underlying news events.

Shani and Westphal [2016] suggest that journalists who engage in negative coverage of a firm tend to distance themselves from other executives in that firm's social network. As a result, these journalists are more likely to write negatively about these other connected firms. Their finding suggests a potential spillover of journalist coverage, in which a journalist's ties to a firm positively influence reporting about other firms in the social network of the connected firm. To probe this possibility, I expand my analysis and examine the news coverage of firms in the network of the acquirer to which a journalist is connected. Specifically, I focus on the network of directors of the acquirer. From BoardEx, I gather data on all outside directors who sit on the board of the acquirer at the time of the transaction. I then collect names of the (public) firms where these directors are currently working. Next, I use Factiva to collect all news articles published in the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times about the directors’ firms (i.e., second-degree connected firms) within one year of the M&A announcement. Because the number of M&As conducted by the directors’ firms is small and overlaps with the M&A news sample, I include other business news in this analysis. These other events include (1) earnings news, (2) corporate governance events (e.g., compensation, executive turnovers, accounting fraud, shareholder voting), (3) product market events, and (4) other major financial news such as debt restructuring or bankruptcies.18

Panel B of table 3 reports the analysis of spillovers. I regress Negative slant (of the articles concerning the directors’ firms) on a dummy variable, CONNECT_Indirect, which flags journalists who have indirect ties to the director's company through their network with the acquirer firm. These tests include media outlet fixed effects and firm × year-month fixed effects. The latter fixed effects ensure that I make comparisons of slant within the same director firm's events in the same year-month. The coefficient on CONNECT_Indirect thus identifies the spillover effect of a second-degree social tie. Column 1 in Panel B shows that the estimate of CONNECT_Indirect is negative and significant at the 5% level. Relative to other articles about the same firm's events in the same year-month, indirectly connected journalists use 39% fewer negative words when describing the directors’ firms in the acquirer's network.

In the second column of panel B, I compare the direct (first-degree) network effect to the spillover. This regression is similar to that in column 1 of panel B but additionally includes a dummy variable, CONNECT_Direct, which identifies journalists who have direct social ties to the director's company. CONNECT_Direct equals one if the article is written by journalists with a direct working relationship, university tie, or Twitter connection to the company management, and zero otherwise. The result confirms the existence of both direct and spillover effects. The direct effect exceeds the spillover effect, with a 43% decrease in negative slant associated with a direct social tie compared to a 33% decrease with a second-degree tie. Although a smaller effect, the spillover is still economically meaningful and statistically significant.

4.4 EXTERNAL VALIDITY: EVIDENCE FROM ACCOUNTING FRAUDS

To evaluate the external validity and generalizability of my findings, I analyze a different type of financial news: accounting fraud. Firms charged with fraud often face intense public scrutiny. The sentiment of news coverage in these cases can either exacerbate or alleviate the public's response to these crises. Therefore, I examine differences in media coverage of accounting fraud by independent versus connected journalists.

I follow prior studies to focus on the SEC's investigations of alleged securities law violations (e.g., Files [2012]). To identify fraudulent firms, I search the SEC's Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases between 1997 and 2016. For media coverage, I use Factiva to collect publications from the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. Like in the M&A news analysis, I use a pooled event panel where the same fraud firm is covered by both newspapers. This leads to a final sample of 229 and 149 articles in the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times, respectively.19 Unsurprisingly, these articles are much more negative than the M&A stories: The mean negative slant is 5%. As in the main analysis, I use equation (2) to test for the network effect on media slant.

Table 3, panel C, reports the results. As in the M&A news, journalist ties, whether through working relationships or university networks, are associated with significantly fewer negative words in reporting accounting fraud.20 These findings corroborate the evidence of network effects observed from the M&A news reporting.21

5 Consequences of Journalist Networks

In this section, I explore potential market outcomes of media bias in firm-journalist networks. The first part of the analysis is anchored in the predictions of behavioral theories to ascertain whether connected articles are associated with stock market and deal outcomes. In the second part, I examine whether journalists’ ties to companies relate to journalists’ long-term career choices.

5.1 JOURNALIST NETWORKS AND STOCK MARKET RETURNS

5.1.1 Media Article Publication Returns

Table 4 reports the results using Wall Street Journal articles. Column 1 shows that the coefficient on working relationship is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. The effect is also economically significant. Based on the estimate, connected articles are associated with 1.6% higher CAR. This magnitude is comparable to those observed in other studies that examine the network effects on M&A returns. For example, Cai and Sevilir [2012] show that acquirer-target board connections improve bidders’ CAR by two percentage points. Consistent with the message in the work of Engelberg, McLean, and Pontiff [2018], the magnitude of stock reactions is larger on important event days, such as when M&As are announced, than on other days.23

| Dependent variable = CAR[0,1] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Network | Work | University | Work | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| OLS | OLS | OLS | 2SLS | |

| CONNECT | 0.016** | 0.001 | 0.046* | 0.034* |

| (0.008) | (0.021) | (0.026) | (0.020) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,127 | 1,127 | 1,127 | 318 |

| R2 | 0.126 | 0.120 | 0.122 | 0.292 |

- This table shows the relation between journalist ties and stocks’ cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) around the news publication date. The dependent variable is acquirer CAR[0,1], constructed upon the Wall Street Journal article publication date. Columns 1 through 3 use OLS regressions; column 4 reports the second stage 2SLS results where CONNECT_WORK is instrumented with connected journalists’ turnover. Control variables include relative deal size, toehold, hostile, unsolicited, cross-industry, financing (all cash), financing (all equity), firm size, Tobin's Q, leverage, cash, profitability, CEO age, CEO duality, and classified board. Definitions of all variables appear in online appendix 1. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are double-clustered by year and by industry. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

With respect to university ties, the evidence of impact weakens. The estimate in column 2 is positive but insignificant. This might be partly attributed to the low variation of university ties in the data, which renders the estimate less informative. As for social media networks, column 3 shows that Twitter ties are also significantly associated with a higher CAR. However, due to the low variation in the data, I caution against making strong inferences from the tests that examine university and social media ties.

Finally, column 4 of table 4 investigates the robustness of the result in column 1 by instrumenting connected coverage with journalist turnover (promotion). The turnover subsample, as described in section 4.2, is used in this analysis. The model yields qualitatively similar results to those reported in column 1.24

5.1.2 Cross-Sectional Analyses of Publication Return

In this section, I explore three behavioral models that could explain how nonfundamental information in the media impacts equity pricing. These models are the theory of noise traders (e.g., DeLong et al. [1990]), the model of liquidity traders (Campbell, Grossman, and Wang [1993]), and the model of investors’ limited attention (Barber and Odean [2008]).

First, I consider different levels of rational arbitrageurs. DeLong et al. [1990] show that noise traders could lead asset prices to deviate from their fundamental values because noise traders deter rational arbitrageurs from betting against them. This model predicts that a high level of rational traders attenuates the media network effect on stock returns. To proxy for the level of shares held by rational traders, I use analyst coverage, total asset size, and the percentage of institutional ownership, following Gleason and Lee [2003], Kumar [2009], and Barber and Odean [2013]. In the CAR regression, I interact these proxies with CONNECT_WORK. Columns 1−3 in table 5, panel A, show that all estimates on the interaction coefficient are negative and statistically significant. These findings are consistent with the argument that firms traded by more rational arbitrageurs are less subject to the network effect.

| Panel A: Heterogeneous effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable = CAR[0,1] | |||||

| Arbitrage Opportunities | Liquidity | Salience | |||

| Proxy | #Analyst | Firm Size | Institution Ownership | Amihud Illiquidity | Front-Page |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| CONNECT_WORK × Proxy | −0.001** | −0.011** | −0.064** | 0.134*** | 0.031** |

| (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.026) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Proxy | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.008 | −0.006 | −0.003 |

| (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.012) | (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| CONNECT_WORK | 0.036** | 0.119*** | 0.054** | 0.013** | −0.006 |

| (0.014) | (0.041) | (0.020) | (0.006) | (0.010) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,127 | 1,127 | 1,127 | 1,127 | 1,127 |

| R2 | 0.131 | 0.136 | 0.134 | 0.151 | 0.134 |

| Panel B: Long-run returns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | CAR[0,1] | CAR[2,40] | CAR[0,40] | CAR[−1,complete] |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| CONNECT_WORK | 0.016** | −0.025** | −0.008 | 0.029 |

| (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.031) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,127 | 1,127 | 1,127 | 847 |

| R2 | 0.126 | 0.087 | 0.084 | 0.096 |

- Panel A reports the results on interaction effects between Wall Street Journal journalist tie and proxies for the arbitrage opportunity, liquidity, and salience. The dependent variable is acquirers’ cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) from the article publication day (day 0) until the following day. The proxies for the level of arbitrage opportunities are #Analysts (column 1), firm size (column 2), and institutional ownership (column 3). The proxy for stock liquidity is Amihud's [2002] illiquidity measure (column 4). The proxy for salience is a dummy variable that indicates whether the article is on the front page of the newspaper (column 5). Panel B shows the relation between CONNECT_WORK and long-run return reactions. Columns 1 replicates the results of bidder's CAR over [0,1]. The dependent variable in columns 2 is acquirers’ CAR over [2,40]. The dependent variable in columns 3 is acquirers’ CAR over [0,40]. The dependent variable in columns 4 is CAR from the day before the deal announcement until the deal completion date (for the subsample of completed deals). Control variables include relative deal size, toehold, hostile, unsolicited, cross-industry, financing (all cash), financing (all equity), firm size, Tobin's Q, leverage, cash, profitability, CEO age, CEO duality, and classified board. Definitions of all variables appear in online appendix 1. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are double-clustered by year and by industry. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Second, I test the channel of stock liquidity (Campbell, Grossman and Wang [1993]). In their model, liquidity traders, facing downward-sloping demand for risky assets, sell shares when there is a negative belief shock, as proxied by media sentiment, and pressure stock prices downwards. Like Guay, Samuels, and Taylor [2016], I use Amihud's [2002] illiquidity measure, which gauges the impact of trading volume on a stock's absolute return. Because this measure captures the illiquidity of a stock, I find a positive estimate of the interaction coefficient, significant at the 1% level (see column 4 of table 5).

Third, I examine limited attention. Investors’ limited attention could lead them to incorporate only information from one source but not rational expectations from other sources (Barber and Odean [2008]). If investor attention matters, front-page news articles should be accompanied by larger price changes (Fedyk [2024]). However, if investors are not constrained by limited attention, there would not be a difference in stock reactions to articles placed on the front page or elsewhere. For each article, I classify whether it appears on the front page of the Wall Street Journal or somewhere else inside the newspaper. Column 5 of table 5, panel A, shows that front-page articles are associated with significantly greater reactions to connected news, confirming the channel of investors’ attention.

5.1.3 Long-Run Stock Returns

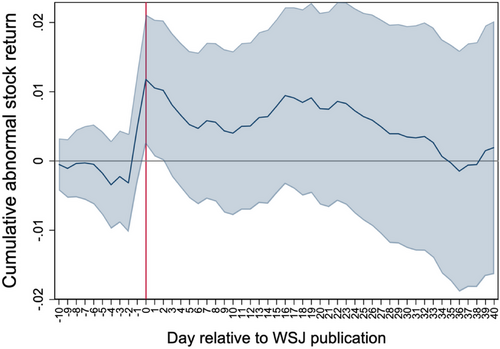

To further distinguish between the hypotheses of information transmission (H1) and favoritism (H2), I study acquirers’ long-term returns. Intuitively, if the higher short-run return to connected news is driven by bias rather than information, a stock price correction is expected in the long run (Tetlock [2007]). This intuition is supported by figure 2, which depicts the univariate comparison of the daily CAR around media publications. It offers several insights. First, there is no significant difference in returns between connected and unconnected firms on each single day before publication day t. Second, consistent with the findings presented in table 4, returns to connected articles are significantly higher immediately upon the news release. Finally, and most importantly, the higher abnormal returns to connected firms gradually disappear in the long term.

To formalize this pattern, I use a multivariate regression framework in table 5, panel B. To facilitate comparison between tables, I first replicate the short-term returns regressions in column 1. The results in column 2 suggest that firms with journalist ties are associated with significantly more negative returns over the [2,40] window, supporting the long-run price correction conjecture (H2).25 The postannouncement price reversal completely offsets the initially more favorable responses to connected firms. Indeed, when the short- and long-run returns are combined, column 3 reveals that the difference in returns between connected and independent firms is indistinguishable from zero. Moreover, column 4 examines acquirer CAR from one day before the deal announcement until the deal completion date. Studying acquirer returns over this longer event window allows me to evaluate differences in stock price revaluation between connected and unconnected firms (Malmendier, Opp, and Saidi [2016]). The result again suggests similar overall returns between connected and unconnected firms.

Taken together, the evidence rejects the hypothesis that favorable coverage in the connected news stories represents value-relevant information. Although studies suggest that media disseminate and create information (e.g., Bushee et al. [2010]), my findings offer a caveat: Whereas independent media facilitate price discovery, biased media coverage due to a connection effect may impede this process.

5.2 JOURNALIST NETWORKS AND ATTRIBUTES OF THE BIDDING PROCESS

In this section, I explore the relation between journalist ties and M&A bidding. Recent studies suggest that individuals often rely on heuristics in decision making, even during competitive auctions (Lacetera, Pope, and Sydnor [2012]). Additionally, models of inattention postulate that salience can distort how individuals react to information (DellaVigna [2009]). For example, Dutordoir, Strong and Sun [2022] show that people tend to home in on M&A announcement returns to infer investment synergies while disregarding long-term price correction. Similarly, Fich and Xu [2023] find that such a bias distorts capital allocation.

To investigate whether connected media coverage relates to attributes of the bidding process, I first examine bid competition in the wake of a Wall Street Journal publication.26 If M&A competitors react to a connected positive article, there may be a positive correlation between connected deals and bid competition. In column 1 of table 6, I use a probit model to predict public bid competition. The dependent variable is an indicator for competing bids received by the target firm over [0,40] following the news publication. The regression specification is otherwise similar to that in equation (3). The result suggests that connected articles are correlated with a significant increase in future bids. In column 2, I instrument connected coverage with journalist Turnover. In this subsample of the analysis, I obtain comparable results. Here, journalist ties are associated with an 18% increase in the probability of competing bids.

| Dependent Variable | Competing Bids over [0,40] | Bid Price Upward Revision | Bidding Success | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | 2SLS | Probit | 2SLS | Probit | 2SLS | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| CONNECT_WORK | 0.332** | 0.180* | 0.263* | 0.276*** | −0.033 | −0.071* |

| (0.163) | (0.094) | (0.147) | (0.106) | (0.112) | (0.038) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 895 | 318 | 941 | 318 | 921 | 318 |

| (Pseudo) R2 | 0.276 | 0.224 | 0.274 | 0.161 | 0.449 | 0.392 |

- This table tests whether journalist ties are associated with several attributes of the M&A bids. Columns 1 and 2 examine bid competition. The dependent variable equals one if a competing bid is received in the [0,40] window after the news publication, and zero otherwise. The dependent variable in columns 3 and 4 equals one if an upward price revision is received by the target, and zero otherwise. Columns 5 and 6 examine deal consummation. The dependent variable equals one if the deal is completed, and zero otherwise. In odd-numbered columns, probit models are used. In even-numbered columns, 2SLS regressions are used in which journalist tie is instrumented with connected journalist turnovers. Control variables include relative deal size, toehold, hostile, unsolicited, cross-industry, financing (all cash), financing (all equity), firm size, Tobin's Q, leverage, cash, profitability, CEO age, CEO duality, and classified board. Definitions of all variables appear in online appendix 1. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are double-clustered by year and by industry. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

The increased competition in M&A deals covered by connected journalists may relate to subsequent positive bid price revisions or deal withdrawals from the initial bidders. Columns 3 through 6 of table 6 test these hypotheses. In columns 3 and 4, I examine whether the initial bidders in deals covered by connected reporters are more likely to raise their bids. The results confirm this positive relation. The economic effect is large, with the results in column 4 revealing that the likelihood of a bid revision more than doubles from 11% (at sample means) to 28%.