Economic Determinants and Information Environment Effects of Earnouts: New Insights from SFAS 141(R)

Accepted by Douglas Skinner. We thank Novia Chen, Yoojin Lee, Qin Li, Yifan Li, and Erin McKenzie for excellent research assistance. We benefited from helpful comments and suggestions from an anonymous reviewer and workshop participants at Arizona State University, Boston College, California State Polytechnic University Pomona, London Business School, Tilburg University, University of California Irvine, University of Miami, University of Washington, the 2012 Annual Academic Corporate Reporting & Governance Conference, and the 2012 California Corporate Finance Conference.

ABSTRACT

Contingent considerations (earnouts) in acquisition agreements provide sellers with future payments conditional on meeting certain conditions. Prior research provides evidence that acquiring firms use earnouts to minimize agency costs associated with acquisitions. Using earnout fair value information, recently mandated by SFAS 141(R), we provide new insights into the economic determinants to include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements, including motivations to resolve moral hazard and adverse selection problems, bridge valuation gaps, and retain target firm managers. We document variations in initial earnout fair value estimates and earnout fair value adjustments that correspond with these underlying motivations. We also provide evidence that target managers stay longer with the firm after the acquisition when earnouts are included primarily to retain target managers. Finally, we demonstrate that earnout fair value adjustments required by SFAS 141(R) provide valuable information to market participants and are negatively associated with the likelihood of contemporaneous and future goodwill impairments.

1. Introduction

Contingent considerations (hereafter “earnouts”) are provisions of acquisition agreements that provide sellers with payments conditional on the occurrence of specified future events or meeting certain conditions. These contracted outcomes, which generally extend up to five years after the acquisition, are often based on financial performance measures, such as revenue and earnings targets, and/or nonfinancial performance hurdles, such as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and clinical trial success. Until recently, acquiring firms did not recognize earnouts at the time of the acquisition. Rather, earnouts were recognized when the corresponding contingencies were resolved and the payments made. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) 141(R) (FASB [2007]) altered the accounting treatment of earnouts. The revised standard requires acquiring firms to estimate and recognize the fair value of earnouts at the acquisition date, include earnout fair values in the acquisition purchase price, and adjust earnout fair values in each reporting period as uncertainty is resolved.1 We use this recently mandated earnout fair value information to shed new light on the economic determinants of earnout provisions in acquisition agreements and to investigate the information content of earnout fair value adjustments.

Prior work on earnouts primarily examines when acquiring firms are likely to include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements. Kohers and Ang [2000], Datar, Frankel, and Wolfson [2001], and Chatterjee, Erickson, and Weber [2004] suggest that earnouts help acquiring firms hedge risk and reduce acquisition costs when there is greater information asymmetry about target firms. Kohers and Ang [2000] and Chatterjee, Erickson, and Weber [2004] also provide evidence that acquisition premiums are greater when earnouts are included in acquisition agreements. More recently, Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011] find that earnouts are larger when targets operate in industries with high-growth or high-return volatility, consistent with earnouts being structured to minimize the costs of valuation uncertainty. These studies use earnout samples from the pre-SFAS 141(R) period. In our study, we take advantage of the new earnout fair value information required by SFAS 141(R) to provide new insights into the economic determinants of earnout provisions in acquisition agreements.

We present and test several economic theories for the determinants of earnouts, including motivations to resolve moral hazard and adverse selection problems, bridge valuation gaps, retain target firm managers, and conserve cash. We use the ratio of the initial earnout fair value to the maximum earnout payment amount (EOFV/EOMax) to capture these different economic motivations.

We find that earnout fair values are a smaller percentage of the maximum earnout payment amounts when firms primarily include earnouts to resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps between the acquiring and target firms, which is consistent with high uncertainty underlying these earnouts. For these earnouts, we also find earnout fair value adjustments to be large with high standard deviation, consistent with the resolution of uncertainty over time. In contrast, when acquiring firms include earnouts primarily to help retain target firm managers, earnout fair values are closer to the maximum earnout payment amounts. For these earnouts, we provide evidence that target managers stay longer with the firm after the acquisition. Moreover, earnout fair value adjustments are small, with low standard deviation, and more upward adjustments that resemble adjustments for the time value of money. This is consistent with the inclusion of earnout provisions with high probabilities that earnout thresholds will be met when earnouts are used to retain target firm managers. Finally, when acquiring firms include earnouts to provide effort incentives to target managers, earnout fair values approach the midrange of zero and the maximum earnout payment amount, where effort incentives are greatest.

We also investigate the information content of quarterly earnout fair value adjustments required by SFAS 141(R). Earnout fair value adjustments reflect changes in the acquiring firm's assessment of the target's value and the expected benefits of the acquisition. This information is especially valuable in the context of earnouts, where most target firms are private and the market is not well informed. We document that earnout fair value adjustments provide valuable information to the market in their valuation of acquiring firms. We find that the market response to earnout fair value adjustments is significantly positive, after controlling for the direct effect of these adjustments on reported earnings. This suggests that the market responds favorably to the positive news associated with increases in earnout fair values and unfavorably to the negative news of downward adjustments. Furthermore, these findings are driven primarily by earnouts with income-based financial performance measures.

Finally, we examine the link between earnout fair value adjustments and acquisition-related financial reporting outcomes, specifically, goodwill impairments. Prior research on goodwill impairments provides evidence that managers of acquiring firms delay goodwill impairments opportunistically (Beatty and Weber [2006], Hayn and Hughes [2006], Li et al. [2011], Li and Sloan [2012], Ramanna and Watts [2012]). In contrast to these prior studies, in our earnout setting, goodwill impairments are more likely to be timely and relevant. As predicted, we find that earnout fair value adjustments are negatively associated with the likelihood of contemporaneous and future goodwill impairments.

Our study makes four primary contributions. First, our findings contribute to the literature on earnouts and, more generally, the literature on contract design and incentives. By exploiting the new earnout fair value information required by SFAS 141(R), we provide new insights into previously documented economic determinants of earnout use, while investigating additional unexplored determinants. Specifically, we provide evidence on the relation between earnout characteristics and economic motivations to resolve moral hazard and adverse selection problems, bridge valuation gaps, and retain target firm managers. Second, by examining the information content of earnout fair value adjustments required by SFAS 141(R) and analyzing the impact of these adjustments on market participants’ valuation of acquiring firms, we contribute to understanding how mandated accounting information recognized in financial statements improves the information environment in a way that is relevant to market participants. Third, our evidence on the information content of earnout fair value adjustments contributes to the literature on the reliability of fair value measurements. Finally, our study establishes a link between earnout fair value adjustments and the likelihood of contemporaneous and future goodwill impairments, and contributes to the literature on goodwill impairments by identifying leading and timely indicators of goodwill impairments.

2. Earnouts

2.1 ACCOUNTING FOR EARNOUTS

Accounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion 16 (APB [1970]) initially specified the accounting for earnouts. Under APB 16, future payments to be made as part of a business combination agreement were included in the purchase price and recorded at the acquisition date if these payments were made “unconditionally” with amounts determinable at the acquisition date (e.g., amounts placed in escrow for a specific period of time). If payments were contingent on the outcome of future events, as for earnouts, then these contingent payments were disclosed at the time of acquisition, but not recorded as a liability until the contingency was resolved. When the contingency was resolved, the corresponding payments were recognized as an addition to the purchase price and generally recorded as goodwill.

SFAS No. 141 (FASB [2001a]) superseded APB 16 but did not substantially modify the accounting for, or the disclosure of, earnouts. Overall, the earnout-related information disclosed at that time was minimal and earnouts impacted the acquirers’ financial statements only when the contingencies were resolved and earnout payments were made (or it was reasonably assured they would be made). On the balance sheet, (short-term) liabilities were recognized after the contingencies were resolved but before the payments were made. On the income statement, only indirect expenses were recognized (generally related to goodwill impairments) after earnout payments were made.

In 2007, SFAS 141 was revised to include significant changes to the accounting treatment of earnouts.2 These changes considerably expanded the earnout-related information available and the impact of earnouts on acquirers’ financial statements. Specifically, SFAS 141(R) requires acquiring firms to recognize all assets acquired and liabilities assumed, measured at their fair values as of the acquisition date.3 Accordingly, firms must estimate the fair value of earnouts and include the fair value in the acquisition purchase price as of the acquisition date. In addition, firms must adjust earnout fair values each quarterly reporting period. When earnout payments are in the form of cash payments, transfers of other assets, and/ or equity payments settled with a variable number of shares, earnout fair values are recorded as liabilities. Subsequent adjustments to the fair value of the earnout liabilities must be recorded through earnings at each reporting date until the contingencies are resolved. When earnout payments are in the form of equity payments settled with a fixed number of shares, earnout fair values are recorded as equity, and subsequent settlement differences are accounted for within equity as the contingencies are resolved. Approximately 3% of the earnout provisions in our sample are classified as equity. As a result, our discussion focuses on earnouts that are classified as liabilities.4

2.2 PRIOR LITERATURE ON EARNOUTS

Prior research on earnouts primarily examines the circumstances where earnout provisions are more likely to be included in acquisition agreements. Kohers and Ang [2000] study a sample of earnout provisions over the period 1984–1996, Datar, Frankel, and Wolfson [2001] analyze acquisitions completed between 1990 and 1997, and Chatterjee, Erickson, and Weber [2004] examine a sample of earnouts in the United Kingdom from 1998 to 2001. All three studies reach similar conclusions: earnouts help acquirers hedge risk and reduce acquisition costs when there is a high degree of information asymmetry about target firms. Overall, they find that firms are more likely to include earnout provisions when targets are small, privately held, or service companies; have a high return on assets or large amounts of intangible assets from different industries from the acquirers; or operate in high-tech industries with high research and development (R&D), high sales growth, and high market-to-book ratios. Kohers and Ang [2000] and Chatterjee, Erickson, and Weber [2004] also provide evidence that acquisition premiums are greater when earnouts are included in acquisition agreements. More recently, Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011] examine the terms of earnout provisions included in acquisitions completed between 1994 and 2003. Their findings suggest that earnouts are larger when targets operate in industries with high-growth or high-return volatility, consistent with earnouts being structured to minimize the costs of valuation uncertainty.5

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1 RATIO EOFV/EOMAX

Prior research suggests that earnouts help reduce agency costs in acquisitions. Datar, Frankel, and Wolfson [2001] investigate the occurrence of earnouts, while Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011] study the maximum earnout payment amounts. We take advantage of the newly available earnout fair value information required by SFAS 141(R), specifically the initial earnout fair value (EOFV) and the ratio of the initial earnout fair value to the maximum earnout payment amount (EOFV/EOMax), to shed additional light on the economic determinants of earnout use in acquisition agreements.

EOFV reflects the acquirer's expectations that earnout thresholds will be achieved and future earnout payments will be made, while EOMax represents the maximum payout. Hence, EOFV/EOMax reflects the acquirer's expected earnout payments relative to the maximum payment amount. This ratio captures the following key elements that allow us to provide new insights into the economic motivations of earnouts. First, EOFV/EOMax reflects the acquirer's estimated probabilities that earnout thresholds will be met and future earnout payments will be made. Second, EOFV/EOMax reveals the effort incentives to target managers underlying the earnout provisions. The ratio provides insights into the potential for target managers to receive larger earnout payments through additional effort to the extent that that effort increases the probability of achieving earnout thresholds.6 Finally, EOFV/EOMax provides an approximation of the difference between the target firm's and acquiring firm's expectations. EOFV reflects the acquirer's expected value of the earnout, while the target's expected value of the earnout, although unobservable, likely exceeds the acquirer's expected value, but cannot be greater than EOMax. Therefore, EOFV/EOMax provides insights into the valuation gap between the parties, where valuation gaps increase with smaller ratios.

The following sections outline how we employ the ratio EOFV/EOMax in our predictions of the economic determinants of earnout provisions in acquisition agreements.7 Although a combination of these motivations likely drives earnout contract design, we present hypotheses for each economic determinant holding the other motivations constant.

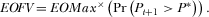

3.2 EARNOUTS TO RESOLVE MORAL HAZARD PROBLEMS

Earnouts help resolve moral hazard problems by linking payouts with measurable outcomes that occur after an acquisition. Effort incentives vary with the probability of meeting earnout thresholds. As an illustration, consider a common earnout contract that pays zero until reaching a threshold performance target P*. For any performance P greater than or equal to P*, the payout is EOMax. Assuming stochastic dominance in effort, where greater effort in time t increases the probability that Pt+1 > P*, it follows that the incentives decrease as |Et(Pt+1) – P*| increases. Thus, the incentives are greatest when Et(Pt+1) = P*.

(1)

(1)- H1:

Ceteris paribus, earnout fair values converge toward the midrange of possible earnout amounts when acquiring firms include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements to resolve moral hazard problems.

Based on the discussion above, we use the ratio EOFV/EOMax to test H1. As EOFV/EOMax approaches one, the target manager's upside potential and returns to effort decline. Similarly, at the other extreme, as EOFV/EOMax approaches zero, the probability of meeting earnout thresholds decreases, which also reduces returns to effort. In contrast, when EOFV/EOMax approaches the midrange of zero and one, the returns to effort are greatest. Thus, the ratio EOFV/EOMax captures the effort incentives earnouts provide to target managers, where the incentives are strongest when EOFV/EOMax approaches the midrange of possible values (i.e., between zero and one), and decrease as EOFV/EOMax moves away from the midrange.

3.3 EARNOUTS TO RESOLVE ADVERSE SELECTION PROBLEMS AND BRIDGE VALUATION GAPS

Earnouts also help resolve agency problems that result from information asymmetry between acquiring and target firms, where greater information asymmetry leads to greater adverse selection problems and greater valuation gaps. Earnouts help resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps by offering payment schedules that are acceptable to both parties, despite their divergent valuations of the target firm (Bruner [2001], Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011]). The target firm will accept the terms of a proposed acquisition when the sum of the initial fixed consideration and the target firm's expected value of the earnout payments are greater than, or equal to, its perceived value of the target. At the same time, the acquiring firm will accept the terms of the transaction when the sum of the initial fixed consideration and the acquirer's expected value of the earnout payments is smaller than, or equal to, its perceived value of the target. Because of divergence in the parties’ expected values of the future earnout payments, earnouts help resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps in acquisitions.

- H2:

Ceteris paribus, earnout fair values are a smaller percentage of maximum earnout payment amounts when acquiring firms include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements to resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps.

3.4 EARNOUTS TO RETAIN TARGET MANAGERS AND CONSERVE CASH

- H3a:

Ceteris paribus, earnout fair values approach maximum earnout payment amounts when acquiring firms include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements to retain target firm managers.

- H3b:

Ceteris paribus, earnout fair values approach maximum earnout payment amounts when acquiring firms include earnout provisions in acquisition agreements to conserve cash in the near term.

Both the desire to retain target managers, who are costly to replace, and to conserve cash provide economic explanations for earnout provisions with high probabilities that earnout thresholds will be met, and corresponding initial earnout fair values that approach maximum earnout payment amounts.

To provide further evidence on H1 through H3b, we investigate characteristics (e.g., magnitude, standard deviation, and direction) of earnout fair value adjustments, and predict that these characteristics vary with the economic motivations of earnout use presented in these hypotheses. Furthermore, to shed additional insights regarding H3a and the motivation to include earnouts to retain target firm managers, we investigate the length of time top-level executives of target firms stay with the firm after the acquisition.

3.5 INFORMATION CONTENT OF EARNOUT FAIR VALUE ADJUSTMENTS

For liability classified earnouts, in addition to reporting initial earnout fair values at the time of the acquisition, SFAS 141(R) requires firms to remeasure earnout fair values and record appropriate adjustments each quarterly reporting period. These earnout fair value adjustments provide information to market participants about the acquiring firms’ revised expectations of the target firms’ future performance and the likelihood that earnout thresholds will be achieved and corresponding earnout payments made. Specifically, an increase in the earnout fair value (i.e., liability) indicates that the likelihood of achieving earnout thresholds is greater than previously anticipated by the acquirer, while a decrease indicates a decline in the expected likelihood of achieving earnout thresholds.

These earnout fair value adjustments also have a direct effect on earnings where an increase (decrease) in the earnout liability results in a decrease (increase) in earnings. Because an increase (decrease) in the liability has a negative (positive) effect on earnings, but reveals a positive (negative) signal about the likelihood of the target achieving earnout thresholds, the effect on earnings contradicts the information revealed.10 This contrast introduces a tension in how market participants view the information provided by earnout fair value adjustments. We predict that market participants value the information provided by earnout fair value adjustments beyond their direct effect on earnings.

- H4:

The market valuation of acquiring firms is associated with the acquisition performance information provided by earnout fair value adjustments.

To provide further evidence on the information content of earnout fair value information, we investigate the relation between earnout fair value adjustments and the likelihood of goodwill impairments.11 Prior studies on goodwill impairments provide evidence that managers of acquiring firms exploit the discretion in SFAS 142 (FASB [2001b]) to opportunistically delay goodwill impairments (Li et al. [2011], Li and Sloan [2012], Ramanna and Watts [2012]).12 These studies, however, identify the need for goodwill impairments at the firm level, generally using market indications of such impairments (e.g., firm-level book-to-market ratio). We contribute to this literature by examining a novel and rich setting. Contrary to acquisitions with no earnout, for acquisitions with earnouts, SFAS 141(R) requires acquiring firms to reestimate every quarter a portion of the acquisition purchase price (i.e., earnout fair values). Adjustments resulting from this reestimation (i.e., earnout fair value adjustments) are prominently disclosed in financial statements, affect reported earnings, and are linked to future verifiable outcomes (i.e., earnout payments). Given that part of the goodwill recorded in an acquisition is likely related to the initial earnout fair value, downward earnout fair value adjustments should coincide with impairments of the related goodwill. As a result, managers of acquiring firms have incentives to record goodwill impairments in a timely manner after adjusting earnout fair values down to maintain their credibility and reputation with market participants. Consequently, in our earnout setting, goodwill impairments are likely to be timely and relevant.

- H5:

Earnout fair value adjustments are negatively associated with the likelihood of goodwill impairments.

Together, H4 and H5 shed light on the information conveyed by earnout fair value adjustments, recently mandated by SFAS 141(R), by examining the effect of the information content of these adjustments on the market's valuation of acquiring firms and on acquisition-related financial reporting outcomes.

4. Data and Sample Selection

4.1 COMPREHENSIVE SAMPLE OF ACQUISITIONS

We obtain data from the Thomson Reuters Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum Mergers and Acquisitions database, the Compustat annual and quarterly databases, the CRSP daily returns database, and the I/B/E/S database. To compile a comprehensive sample of acquisitions with earnout information, we identify acquisitions by U.S. public acquiring firms using the SDC database, which records the maximum amount of earnout payments (if any). We require strictly positive total assets for acquiring firms in the quarterly Compustat database, and sufficient data to construct explanatory variables. We gather additional information by hand-collecting data on acquisitions that are covered by the SDC database but marked as having missing deal values and/or missing maximum earnout payment amounts. For these acquisitions, we search corporate filings in the Securities Exchange Commission's EDGAR database for any earnout-related information.

We compile a comprehensive sample of 10,816 acquisitions over the period from July 1, 2006 to June 30, 2011. Out of these 10,816 acquisitions, 6,734 (4,082) are completed pre- (post-) SFAS 141(R).13 Furthermore, 994 of these acquisitions contain earnout provisions: 618 in the pre- and 376 in the post-SFAS 141(R) period. Approximately 9% of the acquisitions in our comprehensive sample include earnouts, and this fraction remains constant before and after the adoption of SFAS 141(R).

Using a subset of this comprehensive sample, we examine the relation between the adoption of SFAS 141(R) and earnout provisions.14 Specifically, we estimate a probit model of earnout use to test whether the probability of including earnouts in acquisition agreements varies with the adoption of SFAS 141(R), while controlling for acquirer, target, and deal characteristics expected to impact decisions to use earnouts. In unreported tests, and in line with prior research, we find significant positive relations between the probability of earnouts and the following target characteristics: the growth opportunities, R&D intensity, and stock return volatility of the target's industry as well as the likelihood of the target firm being private. We also find significant negative relations between the probability of earnouts and the acquiring firm's leverage as well as the likelihood of the target firm operating in a different industry from the acquiring firm. Finally, we do not find a significant relation between the probability of earnouts and the adoption of SFAS 141(R).15 Overall, our findings indicate that the additional requirements introduced by SFAS 141(R) did not alter acquiring firms’ propensity to include earnouts in acquisition agreements considerably.

4.2 SAMPLE OF POST-SFAS 141(R) EARNOUTS

We compile a sample of acquisitions with earnout provisions completed after the adoption of SFAS 141(R) covering the sample period from January 1, 2009 to June 30, 2011. This process yields a total sample of 329 acquisitions with earnouts, which consists of 321 liability classified earnouts, 4 equity classified earnouts, and 4 earnouts with a portion classified as liability and a portion classified as equity.

To gather additional detailed information on this sample, we hand-collect initial earnout fair value estimates, subsequent earnout fair value adjustments, and earnout design details (such as starting date, length of the earnout measurement period, performance measures, payment structure, etc.) from corporate filings in the EDGAR database (forms 8-K, 10-Q, and 10-K). See appendix A for an example of the earnout-related information available in corporate filings. Finally, using LexisNexis as well as several professional networking sites (e.g., LinkedIn), we hand-collect information on top-level executives of the target firms in our sample (such as founder/ownership information, role in target firm, arrival and departure dates, etc.).

From this sample of post-SFAS 141(R) earnouts, we select specific subsamples based on the focus of the tests and related data requirements. We introduce and define these subsamples as they are employed in our analyses.

5. Economic Determinants of Earnouts

5.1 MODELS AND VARIABLE DEFINITIONS

5.1.1. EOFV/EOMax Values

Following our development of H1 through H3b, we classify observations into three groups based on values of EOFV/EOMax. As discussed in section 3.1, EOFV/EOMax captures key elements that shed new light on the economic determinants of earnouts. Specifically, we conjecture that the ratio reflects different economic motivations across its range of values. Small values of EOFV/EOMax consist of earnout observations for which we predict that the economic motivations to use earnouts to resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps are strong, whereas the motivations to address moral hazard problems are weak. Large values of EOFV/EOMax include earnouts for which we predict that the motivations to include earnouts to resolve adverse selection problems, address moral hazard problems, or bridge valuation gaps are weak, whereas the motivations to retain target managers and conserve cash are strong. Finally, we predict that earnouts with EOFV/EOMax values around the midrange of zero and one reflect instances where effort incentives to address moral hazard concerns are strong. In our tests, we define a “Low,” “Middle,” and “High” group, where the Low (High) group corresponds to values of EOFV/EOMax in the bottom (top) 25%, and the Middle group corresponds to EOFV/EOMax values between 25% and 75%.16

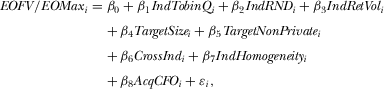

5.1.2. EOFV/EOMax and Economic Determinants of Earnouts

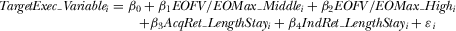

(2)

(2)- EOFV/EOMax

= Initial earnout fair value estimate scaled by the maximum earnout payment amount.

- IndTobinQ

= Median Tobin's Q (Tobin [1969]) of the target's three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement.

- IndRND

= Median R&D-to-sales ratio of the target's three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement.

- IndRetVol

= Annualized volatility of the value-weighted return of the target's three-digit SIC industry, measured over the last 100 days prior to the acquisition announcement.

- TargetSize

= Natural logarithm of the sum of the initial fixed payment for the acquisition and the initial earnout fair value estimate, as a measure of the fair value of the target firm at the time of the acquisition.

- TargetNonPrivate

= Indicator variable equal to one if the target is not a private company (e.g., a public company, a subsidiary, etc.), zero otherwise.

- CrossInd

= Indicator variable equal to one if the acquirer's three-digit SIC industry (primary or secondary SIC) and the target's primary three-digit SIC are different, zero otherwise.

- IndHomogeneity

= Average partial correlation coefficient on the industry return index of the target's three-digit SIC industry, using a two-factor regression model of each firm's stock return on an equal-weighted industry return index and an equal-weighted market index over the five years 2004–2008 (Parrino [1997]).

- AcqCFO

= Acquirer's cash flow from operations scaled by total assets in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement.

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Datar, Frankel, and Wolfson [2001], Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011]), we include the following target industry characteristics: growth opportunities (IndTobinQ), R&D intensity (IndRND), and return volatility (IndRetVol). We also include the size of the target (TargetSize). Information asymmetry between the target and the acquirer is increasing in IndTobinQ, IndRND, and IndRetVol, and decreasing in TargetSize. We conjecture that adverse selection problems and valuation gaps are more severe in acquisitions of firms that are small and from industries with high growth opportunities, R&D, and return volatility. Therefore, we rely on these four proxies of information asymmetry to test H2, which predicts that EOFV/EOMax is small when IndTobinQ, IndRND, and IndRetVol are large and TargetSize is small.

We also identify whether the target is nonprivate (TargetNonPrivate) and operates in a different industry from the acquirer (CrossInd), where information asymmetry between the target and the acquirer is decreasing in TargetNonPrivate and increasing in CrossInd. In line with Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011], we conjecture that the importance of the target managers’ efforts is increasing in cross-industry acquisitions. Also, prior research provides evidence that majority ownership by owner–managers is very common in private firms, but rare in public firms, especially subsidiaries of public firms (Holderness, Kroszner, and Sheehan [1999], Coates [2010], Cain, Denis, and Denis [2011]). Thus, we predict that managers of private target firms will be more responsive to earnout incentives than managers of nonprivate target firms. Therefore, TargetNonPrivate and CrossInd are proxy variables to test H1. Empirically, H1 predicts that EOFV/EOMax falls in the midrange of zero and one when acquiring firms use earnouts to address moral hazard issues, as reflected by TargetNonPrivate equal to zero and CrossInd equal to one.

In some instances, the cost of replacing target managers is sufficiently high such that retaining these managers outweighs the need to offer effort incentives to them. To provide evidence on the use of earnouts to help retain target managers, and avoid the high cost of replacing them, we use a measure of the homogeneity of the target industry that is based on the correlation of returns in the target industry, IndHomogeneity, as in Parrino [1997]. Brickley [2003] suggests that industry homogeneity reflects a deeper pool of potential replacements for existing managers. Thus, less homogeneity in the target industry indicates that the pool of potential managers is small and the cost of replacing target managers is high. Consequently, H3a predicts that EOFV/EOMax is large when IndHomogeneity is low, and acquirers include earnout provisions to help retain target managers. Finally, we consider acquiring firms’ cash flow from operations (AcqCFO) as an additional economic determinant of earnout use. To the extent that acquirers include earnouts to conserve cash, H3b predicts that EOFV/EOMax is large when AcqCFO is low.

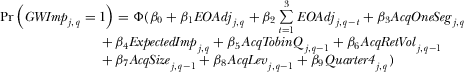

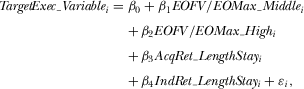

5.1.3. EOFV/EOMax and Target Manager Retention

(3)

(3)- EOFV/EOMax_Middle

= Indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the Middle EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise.

- EOFV/EOMax_High

= Indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the High EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise.

- AcqRet_LengthStay

= Buy-and-hold stock return of the acquirer over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013).

- IndRet_LengthStay

= Buy-and-hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013).

The dependent variable, TargetExec_Variable, represents the following two measures capturing the target manager's length of stay: TargetExec_LengthStayPct is the number of days the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition divided by the total number of days between the acquisition completion date and June 28, 2013; and TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave is the number of years the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition. We focus on the variables EOFV/EOMax_Middle and EOFV/EOMax_High to examine differences in the length of stay of target managers across the groups of EOFV/EOMax. H3a predicts that EOFV approaches EOMax when acquiring firms use earnouts to retain target managers. Consequently, we expect target managers to stay longer with the firm when EOFV/EOMax is large. Finally, we include two additional independent variables to control for factors that potentially impact a target manager's decision to stay or leave the firm: the performance of the acquiring firm (AcqRet_LengthStay) and of the target industry (IndRet_LengthStay) in the period after the acquisition during which the target manager is still with the firm.

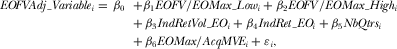

5.1.4. Earnout Fair Value Adjustments and Economic Determinants of Earnouts

To provide additional evidence on H1 through H3b, we investigate characteristics of earnout fair value adjustments required by SFAS 141(R), including magnitude, standard deviation, and direction. Using the fair value adjustments from earnouts designed to help resolve moral hazard problems (where the ratio EOFV/EOMax lies in the midrange of zero and one) as a benchmark, we predict that earnout fair value adjustments reflect the resolution of high uncertainty when firms include earnouts to address adverse selection and valuation gap issues. Specifically, we expect earnout fair value adjustments to be larger, with higher standard deviations, and in different directions (upward or downward) for earnouts with low EOFV/EOMax. In contrast, when firms employ earnouts to retain target managers or delay cash payments, earnout fair value adjustments are more likely to correspond to systematic adjustments for the time value of money. Thus, for earnouts with high EOFV/EOMax, we predict that fair value adjustments exhibit smaller magnitudes and lower standard deviations and are more often upward than downward.

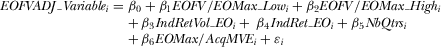

(4)

(4)- EOFV/EOMax_Low

= Indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the Low EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise.

- EOFV/EOMax_High

= Indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the High EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise.

- IndRetVol_EO

= Annualized volatility of the value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry, averaged over all quarters of the observed earnout period.

- IndRet_EO

= Buy-and-hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the observed earnout period.

- NbQtrs

= Number of quarters in the observed earnout period.

- EOMax/AcqMVE

= Maximum earnout payment amount scaled by the acquirer's market value of equity prior to the acquisition completion date.

The dependent variable, EOFVAdj_Variable, represents the following three characteristics of earnout fair value adjustments: EOFV_StdDev is the standard deviation of the underlying earnout fair value divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period, EOFVAdj_Max is the absolute value of the maximum earnout fair value adjustment divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period, and EOFVAdj_UpDownPct is the difference between the number of quarters with upward earnout fair value adjustments and the number of quarters with downward earnout fair value adjustments, divided by the total number of quarters in the observed earnout period, multiplied by 100. The variables of interest EOFV/EOMax_Low and EOFV/EOMax_High are used to examine any differences in earnout fair value adjustment characteristics across the groups of EOFV/EOMax. The other independent variables control for factors that potentially impact the magnitude, standard deviation, and direction of earnout fair value adjustments. These control variables capture the underlying volatility (IndRetVol_EO) and performance (IndRet_EO) of the target industry during the observed earnout period, the number of quarters in the observed earnout period (NbQtrs), and the size of the earnout relative to the size of the acquiring firm (EOMax/AcqMVE).

5.2 SUBSAMPLES AND UNIVARIATE STATISTICS

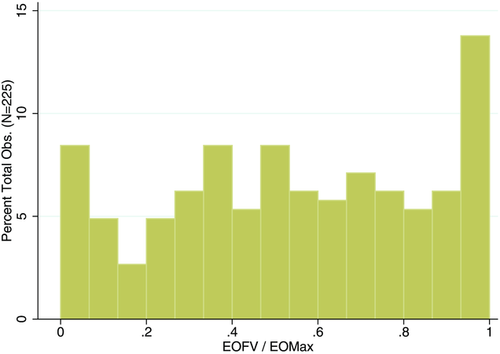

From the sample of acquisitions with earnouts in the post-SFAS 141(R) period described in section 4.2, we select two subsamples to test hypotheses H1 through H3b. First, the “initial earnout fair value subsample” consists of acquisition observations with nonmissing initial earnout fair value estimates and nonmissing maximum earnout payment amounts. This subsample consists of 225 earnout observations and is used to estimate equation 2. Figure 1 plots the histogram of all EOFV/EOMax values for this subsample. To estimate equation 3, we focus on a subset (162 earnout observations) of this subsample for which we have relevant information on top-level target executives and available data for the related control variables.

Second, the “earnout fair value adjustment subsample” consists of acquisition observations with liability classified earnouts, nonmissing initial earnout fair value estimates, nonmissing maximum earnout payment amounts, and at least three quarters of earnout fair value adjustments. This subsample consists of 215 earnout observations and is employed to estimate equation 4.18

Table 1 provides univariate statistics of the variables in equations 2 and 3 for the initial earnout fair value subsample as a whole and across the three groups of EOFV/EOMax. Table 1 also reports the statistical significance from t-tests for differences in means for all variables (chi-square tests for differences in distributions for the indicator variables, TargetNonPrivate and CrossInd). For the subsample as a whole, the mean and median EOFV/EOMax ratio is 0.54, close to the midrange of zero and one, where we conjecture that firms include earnouts primarily to address moral hazard concerns. Looking across the EOFV/EOMax groups, consistent with our predictions, earnouts in the High group, where earnouts are not primarily included to resolve adverse selection problems, are related to target firms that operate in industries where the R&D intensity is significantly lower than in the Low or Middle groups. Also as expected, target firms in the Low group are more likely to be nonprivate firms compared to the Middle group or the High group. Next, contrary to our prediction, the acquiring firms in the Low group have lower cash flow from operations than acquiring firms in the Middle or High groups. Finally, for the variables used in equation 3, target managers’ length of stay with the firm after the acquisition is significantly longer for earnouts in the High group, included primarily to retain target managers, than for earnouts in the Low group, as expected.

| Low (N = 47) | Middle (N = 108) | High (N = 70) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOFV/ | 0.25 < EOFV/ | EOFV/ | ||||||

| All (N = 225) | EOMax ≤ 0.25 | EOMax < 0.75 | EOMax ≥ 0.75 | |||||

| Variable | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median |

| EOFV/EOMax | 0.54 | 0.54 | ||||||

| IndTobinQ | 1.54 | 1.45 | 1.51 | 1.47 | 1.56 | 1.47 | 1.51 | 1.40 |

| IndRND | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07* | 0.06 | 0.07* | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| IndRetVol | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| TargetSize (in $M) | 88.64 | 29.93 | 65.82 | 31.00 | 101.61 | 31.35 | 83.95 | 24.64 |

| TargetSize (Log) | 3.39 | 3.40 | 3.30 | 3.43 | 3.46 | 3.44 | 3.34 | 3.20 |

| TargetNonPrivate | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.32*,** | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CrossInd | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 |

| IndHomogeneity | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| AcqCFO | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.05*,** | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| TargetExec_LengthStayPct | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.63* | 0.84 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave (in years) | 2.33 | 2.74 | 2.01* | 2.18 | 2.28 | 2.57 | 2.59 | 2.99 |

| AcqRet_LengthStay | 0.42 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.03 |

| IndRet_LengthStay | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.34 |

- Summary statistics for the initial earnout fair value subsample as a whole and for the Low, Middle, and High EOFV/EOMax groups, along with statistical significance from t-tests for differences in means (chi-square tests for differences in distributions for TargetNonPrivate and CrossInd) across the Low, Middle, and High EOFV/EOMax groups. The Low (High) group corresponds to values of EOFV/EOMax in the bottom (top) 25%, and the Middle group corresponds to EOFV/EOMax values between 25% and 75%. The variables TargetExec_LengthStayPct, TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave, AcqRet_LengthStay, and IndRet_LengthStay relate to a subset (162 earnout observations) of the initial earnout fair value subsample with data to estimate equation 3 (31, 77, and 54 earnout observations in the Low, Middle, and High EOFV/EOMax groups, respectively, in this subset).

- Variable Definitions: EOFV/EOMax is the initial earnout fair value estimate scaled by the maximum earnout payment amount. IndTobinQ is the median Tobin's Q of the target's three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. IndRND is the median R&D to sales ratio of the target's three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. IndRetVol is the annualized volatility of the value-weighted return of the target's three-digit SIC industry, measured over the last 100 days prior to the acquisition announcement. TargetSize in $M (Log) is (the natural logarithm of) the sum of the initial fixed payment for the acquisition and the initial earnout fair value estimate, as a measure of the fair value of the target firm at the time of the acquisition, in $M. TargetNonPrivate is an indicator variable equal to one if the target is not a private company (e.g., a public company, a subsidiary, etc.), zero otherwise. CrossInd is an indicator variable equal to one if the acquirer's three-digit SIC industry (primary or secondary SIC) and the target's primary three-digit SIC are different, zero otherwise. IndHomogeneity is the average partial correlation coefficient on the industry return index of the target's three-digit SIC industry, using a two-factor regression model of each firm's stock return on an equal-weighted industry return index and an equal-weighted market index over the five years 2004–2008 (Parrino [1997]). AcqCFO is the acquirer's cash flow from operations scaled by total assets in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. TargetExec_LengthStayPct is the number of days the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition divided by the total number of days between the acquisition completion date and June 28, 2013. TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave is the number of years the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition. AcqRet_LengthStay is the buy-and-hold stock return of the acquirer over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013). IndRet_LengthStay is the buy-and-hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013). All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. *Statistically different from the High group p < 0.10. **Statistically different from the Middle group p < 0.10.

Similar to table 1, table 2 provides univariate statistics of the variables in equation 4 for the earnout fair value adjustment subsample. The mean and median EOFV/EOMax ratio for this subsample is 0.56, again close to the midrange of zero and one. Moreover, the mean and median lengths of observed earnout periods are six quarters.19 Turning to the results across the EOFV/EOMax groups, when moving from the High group to the Middle group, and from the Middle group to the Low group, EOFV_StdDev and EOFVAdj_Max both increase significantly. That is, earnout fair value adjustments are larger in magnitude with greater standard deviations when earnouts are more likely to be used to address adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps, which supports our conjectures on the determinants of earnouts. We also find that earnouts in the High group have more upward earnout fair value adjustments than earnouts in the Middle and Low groups, also consistent with our predictions.

| Low (N = 39) | Middle (N = 108) | High (N = 68) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOFV/ | 0.25 < EOFV/ | EOFV/ | ||||||

| All (N = 215) | EOMax ≤ 0.25 | EOMax < 0.75 | EOMax ≥ 0.75 | |||||

| Variable | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median |

| EOFV/EOMax | 0.56 | 0.56 | ||||||

| EOFV_StdDev | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.51*,** | 0.32 | 0.32* | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| EOFVAdj_Max | 49.24 | 20.24 | 84.08*,** | 58.21 | 51.53* | 29.80 | 25.61 | 6.38 |

| EOFVAdj_UpDownPct | 12.73 | 0.00 | −1.65* | −12.50 | 10.92* | 10.56 | 23.84 | 5.56 |

| IndRetVol_EO | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| IndRet_EO | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| NbQtrs | 6.08 | 6.00 | 6.26 | 6.00 | 6.04 | 6.00 | 6.04 | 5.50 |

| EOMax/AcqMVE | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07*,** | 0.04 | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

- Summary statistics for the earnout fair value adjustment subsample as a whole and for the Low, Middle, and High EOFV/EOMax groups, along with statistical significance from t-tests for differences in means across the Low, Middle, and High EOFV/EOMax groups. The Low (High) group corresponds to values of EOFV/EOMax in the bottom (top) 25%, and the Middle group corresponds to EOFV/EOMax values between 25% and 75%.

- Variable Definitions: EOFV/EOMax is the initial earnout fair value estimate scaled by the maximum earnout payment amount. EOFV_StdDev is the standard deviation of the underlying earnout fair value divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period. EOFVAdj_Max is the absolute value of the maximum earnout fair value adjustment divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period. EOFVAdj_UpDownPct is the difference between the number of quarters with upward earnout fair value adjustments and the number of quarters with downward earnout fair value adjustments, divided by the total number of quarters in the observed earnout period, multiplied by 100. IndRetVol_EO is the annualized volatility of the value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry, averaged over all quarters of the observed earnout period. IndRet_EO is the buy-and-hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the observed earnout period. NbQtrs is the number of quarters in the observed earnout period. EOMax/AcqMVE is the maximum earnout payment amount scaled by the acquirer's market value of equity prior to the acquisition completion date. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. *Statistically different from the High group p < 0.10. **Statistically different from the Middle group p < 0.10.

5.3 RESULTS

Table 3 presents parameter estimates of equation 2. Standard errors are clustered by target industry because we measure several variables at the target industry level. Column (1) presents estimates of an ordinary least squares estimation, whereas columns (2) and (3) present estimates of a multinomial probit estimation. Starting with the results in column (1), we find that EOFV/EOMax is significantly negatively related to IndRND. This negative relation is consistent with H2, which predicts that earnouts are implemented, in part, to resolve adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps. We also find a significantly negative (yet, relatively weak) relation between EOFV/EOMax and IndHomogeneity (t-statistic = –1.74). This result supports H3a, and is consistent with acquiring firms including earnout provisions to help retain target firm managers.

| Multinomial Probit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Low vs. Middle | High vs. Middle | |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| IndTobinQ | 0.010 | −0.433 | −0.125 |

| (0.134) | (−0.819) | (−0.322) | |

| IndRND | −0.673** | 0.437 | −4.929*** |

| (−2.438) | (0.312) | (−2.719) | |

| IndRetVol | −0.110 | 1.043 | −0.226 |

| (−0.559) | (0.781) | (−0.180) | |

| TargetSize | 0.007 | −0.013 | 0.033 |

| (0.530) | (−0.134) | (0.358) | |

| TargetNonPrivate | −0.067 | 0.587** | 0.018 |

| (−1.561) | (2.068) | (0.056) | |

| CrossInd | 0.062 | −0.447* | −0.056 |

| (1.175) | (−1.928) | (−0.157) | |

| IndHomogeneity | −0.701* | −0.773 | −4.561** |

| (−1.735) | (−0.224) | (−2.013) | |

| AcqCFO | 0.403 | −3.456** | −0.781 |

| (1.169) | (−2.458) | (−0.421) | |

| Constant | 0.607*** | 0.153 | 0.657 |

| (3.659) | (0.161) | (0.862) | |

| Observations | 225 | 225 | 225 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.030 | ||

| Chi-square | 60.39 | 60.39 | |

| p-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

- Standard errors are clustered at the three-digit SIC target industry level. Column (1) presents estimates of an ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. Columns (2) and (3) present estimates of a multinomial probit estimation. Column (2) (column 3) presents results of the likelihood that an earnout is in the Low (High) group compared to the Middle group. The Low (High) group corresponds to values of EOFV/EOMax in the bottom (top) 25%, and the Middle group corresponds to EOFV/EOMax values between 25% and 75%.

- Variable Definitions: IndTobinQ is the median Tobin's Q of the target three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. IndRND is the median R&D to sales ratio of the target three-digit SIC industry in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. IndRetVol is the annualized volatility of the value-weighted return of the target three-digit SIC industry, measured over the last 100 days prior to the acquisition announcement. TargetSize is the natural logarithm of the sum of the initial fixed payment for the acquisition and the initial earnout fair value estimate, as a measure of the fair value of the target firm at the time of the acquisition. TargetNonPrivate is an indicator variable equal to one if the target is not a private company (e.g., a public company, a subsidiary, etc.), zero otherwise. CrossInd is an indicator variable equal to one if the acquirer three-digit SIC industry (primary or secondary SIC) and the target primary three-digit SIC are different, zero otherwise. IndHomogeneity is the average partial correlation coefficient on the industry return index of the target three-digit SIC industry, using a two-factor regression model of each firm stock return on an equal-weighted industry return index and an equal-weighted market index over the five years 2004–2008 (Parrino [1997]). AcqCFO is the acquirer cash flow from operations scaled by total assets in the fiscal year prior to the acquisition announcement. All continuous independent variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. t-statistics are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Columns (2) and (3) of table 3 present results from the estimation of a multinomial probit model used to predict the likelihood of EOFV/EOMax categorical outcomes given a set of explanatory variables. In our context, the three categorical outcomes are earnouts in the Low, Middle, and High groups, and the covariates are those included in equation 2 and defined in section 5.1.2.. Column (2) presents results of the likelihood that an earnout is in the Low group compared to the Middle group, and column (3) the likelihood that an earnout is in the High group compared to the Middle group. We find that earnouts with target firms operating in high R&D intensity industries are significantly less likely to be in the High group compared to the Middle group, that is, less likely to have large values of EOFV/EOMax. This result is consistent with H2 and provides evidence that retaining target managers and conserving cash are not determinants of earnout provisions when target firms operate in high R&D industries.

We find that earnouts with nonprivate target firms are more likely to be in the Low group compared to the Middle group, and target firms operating in different industries from acquiring firms are less likely to be in the Low group compared to the Middle group. These findings are consistent with the prediction in H1 that private targets and target firms operating in different industries from acquiring firms are more likely to be in the Middle group, where the effort incentives to resolve moral hazard concerns are the greatest.

Finally, we document that earnouts with targets in less homogeneous industries are more likely to be in the High group compared to the Middle group. This result supports H3a by providing evidence that EOFV/EOMax is large when target industry homogeneity is low and acquiring firms have greater incentives to retain target firm managers. We also find that earnouts are less likely to be in the Low group compared to the Middle group when acquiring firms have high levels of cash flow from operations (and therefore are less cash constrained). This result is not consistent with the prediction in H3b that EOFV/EOMax is large when acquiring firms have low levels of cash flow from operations (and are more cash constrained). Overall, we do not find evidence in support of H3b.

Table 4 presents parameter estimates of equation 3. Standard errors are clustered by target industry. Column (1) presents estimates of an ordinary least squares estimation using TargetExec_LengthStayPct as the dependent variable to capture the target manager's length of stay with the firm after the acquisition. The results in column (1) indicate that a target manager's length of stay with the firm is longer for earnouts where EOFV/EOMax is in the High group compared to the Low group. This is consistent with H3a and suggests that, when EOFV is close to EOMax, and earnouts are included primarily to retain target managers, target managers stay with the firm longer after the acquisition.

| OLS | Hazard Model | |

|---|---|---|

| TargetExec_LengthStayPct | TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave | |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

| EOFV/EOMax_Middle | 0.071 | 0.574** |

| (1.324) | (−2.176) | |

| EOFV/EOMax_High | 0.144* | 0.453*** |

| (1.879) | (−2.614) | |

| AcqRet_LengthStay | 0.027 | 1.173 |

| (0.706) | (0.745) | |

| IndRet_LengthStay | 0.546*** | 0.046*** |

| (4.498) | (−3.615) | |

| Constant | 0.414*** | |

| (5.190) | ||

| Observations | 162 | 139 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.325 | |

| LogL | −169.5 |

- Standard errors are clustered at the three-digit SIC target industry level. Column (1) presents estimates of an ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. Column (2) presents estimates of a duration analysis using a Cox proportional hazard model with single-record, single-failure data, where the failure is the latest departure date of all target executives in our model. Column (2) reports hazard ratios and z-statistics of the estimated coefficients. The estimation of this model requires that a target manager stays at least one day with the firm after the acquisition.

- Variable Definitions: TargetExec_LengthStayPct is the number of days the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition divided by the total number of days between the acquisition completion date and June 28, 2013. TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave is the number of years the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition. EOFV/EOMax_Middle is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the Middle EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise. EOFV/EOMax_High is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the High EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise. AcqRet_LengthStay is the buy-and-hold stock return of the acquirer over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013). IndRet_LengthStay is the buy-and-hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the length of stay of the target manager (i.e., between the acquisition completion date and the earliest of (1) the target manager leave date and (2) June 28, 2013). AcqRet_LengthStay and IndRet_LengthStay are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. t-/z-statistics are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Column (2) presents estimates of a duration analysis using a Cox proportional hazard model with single-record, single-failure data, where the failure is the latest departure date of all target executives in our model. Column (2) reports hazard ratios and z-statistics of the estimated coefficients. The dependent variable TargetExec_LengthUntilLeave captures the amount of time the target manager stays with the firm after the acquisition. The estimation of this model requires that a target manager stays at least one day with the firm after the acquisition.

As presented in column (2), the hazard ratio is 0.45 for target managers when earnouts are in the High EOFV/EOMax group and 0.57 when earnouts are in the Middle group. In an untabulated test, we do not find a statistical difference between the hazard ratios in these two groups. Overall, the results in this column indicate that, when earnouts are in the High EOFV/EOMax group, target managers stay with the firm after the acquisition longer than when earnouts are in the Low group. Similar to the findings in column (1), this result supports H3a and is consistent with target managers staying longer with the firm when earnouts are included to retain target managers. Finally, columns (1) and (2) provide evidence that target managers stay significantly longer with the firm after the acquisition if the performance of the target industry is better, which increases the likelihood that earnout payments will be made.

Table 5 presents parameter estimates of an ordinary least squares estimation of equation 4 using EOFV_StdDev (column 1), EOFVAdj_Max (column 2), and EOFVAdj_UpDownPct (column 3) as dependent variables to capture earnout fair value adjustment characteristics. For all columns, standard errors are clustered by target industry. We first examine the Low EOFV/EOMax group. In this Low group, we find that the variation of earnout fair values is significantly greater, the maximum fair value adjustment is significantly larger, and the proportion of quarters with upward adjustments is significantly smaller, than in the Middle and High groups. These findings are consistent with earnout fair value adjustments that reflect the resolution of high uncertainty over time when earnouts are designed to help address adverse selection problems and bridge valuation gaps.

| EOFV_StdDev | EOFVAdj_Max | EOFVAdj_UpDownPct | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| EOFV/EOMax_Low | 0.175** | 31.929* | −15.689** |

| (2.144) | (1.948) | (−2.064) | |

| EOFV/EOMax_High | −0.179*** | −26.596*** | 14.077* |

| (−3.088) | (−2.831) | (1.963) | |

| IndRetVol_EO | 0.559 | 95.804 | |

| (1.356) | (1.328) | ||

| IndRet_EO | −19.367 | ||

| (−1.383) | |||

| NbQtrs | 0.022** | 4.245** | 0.902 |

| (2.044) | (2.014) | (0.467) | |

| EOMax/AcqMVE | 0.121 | −13.879 | 102.190** |

| (0.335) | (−0.236) | (2.259) | |

| Constant | 0.056 | 4.370 | 5.827 |

| (0.457) | (0.180) | (0.538) | |

| EOFV/EOMax_High vs. Low | −0.354*** | −58.525*** | 29.766*** |

| (−3.793) | (−3.250) | (3.486) | |

| Observations | 215 | 215 | 215 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.117 | 0.107 | 0.036 |

- Ordinary least squares estimations of earnout fair value adjustment characteristics on EOFV/EOMax groups, where EOFV/EOMax is the initial earnout fair value estimate scaled by the maximum earnout payment amount, and control variables. Standard errors are clustered at the three-digit SIC target industry level.

- Variable Definitions: EOFV_StdDev is the standard deviation of the underlying earnout fair value divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period. EOFVAdj_Max is the absolute value of the maximum earnout fair value adjustment divided by the mean earnout fair value over the observed earnout period. EOFVAdj_UpDownPct is the difference between the number of quarters with upward earnout fair value adjustments and the number of quarters with downward earnout fair value adjustments, divided by the total number of quarters in the observed earnout period, multiplied by 100. EOFV/EOMax_Low is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the Low EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise. EOFV/EOMax_High is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnout is in the High EOFV/EOMax group, zero otherwise. The Low (High) group corresponds to values of EOFV/EOMax in the bottom (top) 25%. IndRetVol_EO is the annualized return volatility of the value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry, averaged over all quarters of the observed earnout period. IndRet_EO is the buy-and- hold value-weighted stock return of the target's three-digit SIC industry over the observed earnout period. NbQtrs is the number of quarters in the observed earnout period. EOMax/AcqMVE is the maximum earnout payment amount scaled by the acquirer's market value of equity prior to the acquisition completion date. IndRetVol_EO, IndRet_EO, and EOMax/AcqMVE are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. t-statistics in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

We next turn to the High EOFV/EOMax group. In this group, we find a significantly smaller variation in earnout fair values, significantly smaller maximum absolute fair value adjustments, and significantly larger proportions of upward adjustments than downward adjustments, compared to the other two groups (Low and Middle). These results are consistent with earnout fair value adjustments that resemble systematic adjustments for the time value of money, and correspond to earnouts used to retain target managers.20

Overall, the findings in tables 1 through 5 provide evidence that initial earnout fair value estimates and earnout fair value adjustments vary in a predictable manner that is consistent with the underlying economic motivations to use earnouts: to provide effort incentives to target managers, resolve adverse selection problems, bridge valuation gaps between acquiring and target firms, and retain target managers.

6. Information Content of Earnout Fair Value Adjustments

6.1 MARKET VALUATION OF EARNOUT FAIR VALUE ADJUSTMENTS

(5)

(5)- BHAR10-Q/-K

= Acquirer's buy-and-hold abnormal returns over the three trading days centered on the 10-Q/-K filing date. Buy-and-hold abnormal returns are measured using raw stock returns minus returns on matched size and book-to-market reference portfolios.

- EarnSurp

= Difference between actual I/B/E/S earnings per share and the average of the most recent individual analyst earnings per share forecasts, scaled by price at the end of the quarter.

- EOFVAdj

= Earnout fair value adjustment scaled by market value of equity at the end of the quarter.

- Accrual

= Difference between (1) income before extraordinary items and discontinued operations and (2) cash flow from operations, scaled by market value of equity at the end of the quarter.22

When estimating equation 5, the coefficient on EOFVAdj captures the market response to earnout fair value adjustments after controlling for the market response to earnings surprises. Since reported earnings include earnout fair value adjustments, the coefficient on EOFVAdj reflects the market valuation of the information revealed in earnout fair value adjustments beyond the direct effect of these adjustments on earnings.23

We gather a sample of 1,114 quarterly earnout fair value adjustments derived from a sample of 262 acquisitions with liability classified earnouts, a subsample of the initial sample of 329 acquisitions with earnouts described in section 4.2 after applying all data requirements to estimate equation 5. Our sample of 1,114 firm-quarter observations consists of 696 nonzero earnout fair value adjustments, with 416 upward adjustments and 280 downward adjustments. The average increase in earnout fair value is $2.6 million, and the average decrease is $4.7 million, corresponding to 3.2 and –5.8 cents per share outstanding, respectively. We further divide our sample of quarterly earnout fair value adjustments into two subsamples based on the underlying performance measures used for earnout thresholds. One subsample of 356 observations contains earnouts with income-based financial performance measures (e.g., net income, earnings per share, earnings before interest and taxes, etc.). The other subsample of 758 observations includes earnouts with performance measures other than income based (e.g., sales, R&D phases, product development, FDA approval, etc.).24

Table 6 presents parameter estimates of equation 5. Standard errors are clustered at both acquiring firm and quarter level. Column (1) includes all quarterly earnout fair value adjustments. In line with prior findings on earnings surprises, we find a positive and significant coefficient on EarnSurp. Furthermore, we find a positive and significant coefficient on EOFVAdj, consistent with a market response that is positively associated with the news in the fair value adjustment after controlling for the effect of the adjustment on earnings. This supports H4 and suggests that the market responds to the information revealed by earnout fair value adjustments beyond their direct effect on reported earnings.

| Performance Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Income-Based | Other | |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| EarnSurp | 1.231*** | 1.903*** | 0.893*** |

| (4.583) | (3.439) | (4.062) | |

| EOFVAdj | 1.101* | 1.785* | 0.802 |

| (1.871) | (1.840) | (0.790) | |

| Accrual | −0.025 | −0.105 | 0.023 |

| (−0.489) | (−1.175) | (0.339) | |

| Constant | −0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| (−0.120) | (−0.164) | (0.236) | |

| Observations | 1,114 | 356 | 758 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.034 | 0.060 | 0.021 |

- Ordinary least squares estimations of acquirer's buy-and-hold abnormal returns on earnings surprises, earnout fair value adjustments, and accruals. Standard errors are clustered at both acquiring firm and quarter level. Column (1) includes all quarterly earnout fair value adjustments. Column (2) includes observations related to earnouts with income-based financial performance measures. Column (3) includes observations related to earnouts with nonincome-based performance measures, as well as 112 observations for which the performance measures were not identified.

- Variable Definitions: BHAR10-Q/-K is the acquirer's buy-and-hold abnormal returns over the three trading days centered on the 10-Q/-K filing date. Buy-and-hold abnormal returns are measured using raw stock returns minus returns on matched size and book-to-market reference portfolios. EarnSurp is the difference between actual I/B/E/S earnings per share and the average of the most recent individual analyst earnings per share forecasts, scaled by price at the end of the quarter. EOFVAdj is the earnout fair value adjustment, scaled by market value of equity at the end of the quarter. Accrual is the difference between (1) income before extraordinary items and discontinued operations and (2) cash flow from operations, scaled by market value of equity at the end of the quarter. All independent variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. t-statistics in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

To further examine how earnout fair value adjustments impact market participants’ valuation of acquiring firms, columns (2) and (3) report results of equation 5 estimated using the subsample of earnouts with income-based financial performance measures and the subsample of earnouts with other performance measures, respectively. We expect earnout fair value adjustments to be more informative to market participants when the underlying performance measures are based on income, since this type of information is generally easier to translate into market values than nonincome or even nonfinancial information. The coefficient on EOFVAdj is positive and significant in column (2) for earnouts with income-based financial performance measures, whereas it is insignificant in column (3) for earnouts with non-income-based performance measures. These results suggest that the findings in column (1) are driven primarily by earnouts with income-based financial performance measures, consistent with our prediction.

The prior literature on fair value information generally documents that market participants find fair value measurements sufficiently reliable to be reflected in their valuation of firms (Landsman [2007], Kolev [2009], Song, Thomas, and Yi [2010]). However, the reliability of fair value measurements greatly depends on the extent of measurement error, whether inputs are observable, and the managerial discretion over the measurements (Maines and Wahlen [2006], Penman [2007]). In our setting, earnout fair value estimates and adjustments are prepared by acquiring firm managers using unobservable inputs and considerable discretion. However, earnout fair values are linked to future verifiable outcomes (i.e., earnout payments). Consequently, and consistent with our findings in table 6, acquiring firm managers have incentives to report accurate earnout fair values that market participants consider in their valuation of acquiring firms.

6.2 EARNOUT FAIR VALUE ADJUSTMENTS AND GOODWILL IMPAIRMENTS

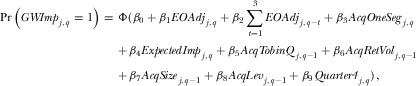

(6)

(6)- GWImpq

= Indicator variable equal to one if a goodwill impairment is recorded in quarter q, zero otherwise.

- EOAdjq

= Earnout fair value adjustment in quarter q scaled by total assets at the beginning of quarter q.

= Sum of the earnout fair value adjustments in the three quarters prior to quarter q scaled by total assets at the beginning of quarter q.

- AcqOneSegq

= Indicator variable equal to one if the firm has a single reporting segment in quarter q, zero otherwise.

- ExpectedImpq

= Indicator variable equal to one if the ratio of the market value to book value of equity is less than one at the beginning of quarter q, zero otherwise.

- AcqTobinQq–1

= Ratio of market value to book value of total assets at the beginning of quarter q.

- AcqRetVolq–1

= Annualized stock return volatility, measured using the standard deviation of daily returns from quarter q – 1.

- AcqSizeq–1

= Natural logarithm of the market value of equity at the beginning of quarter q.

- AcqLevq–1

= Ratio of total liabilities to total assets at the beginning of quarter q.

- Quarter4q

= Indicator variable equal to one if quarter q is the fourth quarter of a fiscal year, zero otherwise.

The variables of interest are EOAdjq and  .26 The other independent variables control for acquiring firm characteristics that prior studies find are related to goodwill impairments in the post-SFAS 142 period (e.g., Beatty and Weber [2006], Li and Sloan [2012], Ramanna and Watts [2012]). Standard errors are clustered at the acquiring firm level.

.26 The other independent variables control for acquiring firm characteristics that prior studies find are related to goodwill impairments in the post-SFAS 142 period (e.g., Beatty and Weber [2006], Li and Sloan [2012], Ramanna and Watts [2012]). Standard errors are clustered at the acquiring firm level.

Table 7 reports mean marginal effects from the estimation of equation 6. Columns (1) and (2) include earnout fair value adjustments in quarter q. We find a significantly negative relation between earnout fair value adjustments in a given quarter q and the probability of goodwill impairments in the contemporaneous quarter q.27 When we allow the coefficients to vary for upward (EOAdjUpq) and downward (EOAdjDownq) earnout fair value adjustments in quarter q, we find that downward earnout fair value adjustments are significantly related to the probability of contemporaneous goodwill impairments, while there is no significant relation with upward earnout fair value adjustments. The findings in columns (1) and (2) provide evidence that earnout fair value adjustments are negatively associated with the likelihood of concurrent goodwill impairments, consistent with H5.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOAdjq | −3.116*** | −3.751*** | ||

| (−3.134) | (−2.770) | |||

| EOAdjUpq | −2.437 | −7.997 | ||

| (−0.602) | (−0.975) | |||

| EOAdjDownq | −3.171*** | −3.755** | ||

| (−2.971) | (−2.423) | |||

| EOAdjq−1, q−3 | −0.922** | |||

| (−2.009) | ||||

| EOAdjUpq−1, q−3 | −2.186 | |||

| (−1.226) | ||||

| EOAdjDownq−1, q−3 | −0.691 | |||

| (−1.317) | ||||

| AcqOneSeg | −0.018 | −0.018 | −0.024 | −0.024 |

| (−1.593) | (−1.595) | (−1.500) | (−1.455) | |

| ExpectedImp | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.035 | 0.033 |

| (1.401) | (1.408) | (1.157) | (1.093) | |

| AcqTobinQ | −0.035* | −0.035* | −0.031 | −0.030 |

| (−1.944) | (−1.937) | (−1.278) | (−1.255) | |

| AcqRetVol | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| (0.178) | (0.185) | (0.115) | (0.089) | |

| AcqSize | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.002 |

| (0.366) | (0.394) | (−0.208) | (−0.345) | |

| AcqLev | −0.026 | −0.026 | −0.022 | −0.024 |

| (−1.040) | (−1.011) | (−0.580) | (−0.635) | |

| Quarter4 | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.064*** | 0.064*** |

| (4.282) | (4.292) | (3.195) | (3.185) | |

| Observations | 1,266 | 1,266 | 667 | 667 |

| LogL | −161.9 | −161.9 | −98.31 | −98.05 |

- Estimations of a probit model of goodwill impairments on earnout fair value adjustments. Mean marginal effects are reported. Standard errors are clustered at the acquiring firm level.