Financial Stress and Indigenous Australians†

This paper uses the general release file of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. HILDA is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and managed by the Melbourne Institute. The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors alone and should not be attributed to either the DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Abstract

We examine the high levels of financial stress among Indigenous populations in Australia. We estimate separate models for the determinants of financial stress for Indigenous and non-Indigenous households and show the importance of separately considering Indigenous disadvantage. We use these models to build equivalence scales for both groups. We find evidence consistent with financial stress being exacerbated by demand sharing (‘humbugging’). The evidence also suggests that financial stress is reduced by engagement in traditional hunting and gathering activities.

1 Introduction

In this paper we estimate models of financial stress (FS) for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and show how these differ. We then use these models of FS to estimate equivalence scales for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. These equivalence scales can be used to equate incomes across households of different size in the same way that consumption-based equivalence scales are used. We show how equivalence scales differ for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and we also consider the special role of remoteness and housing arrangements in understanding Indigenous disadvantage in Australia.

Income and poverty studies in the past have noted that many Indigenous people experience resource deprivation and extreme financial disadvantage relative to other Australian citizens (Henderson, 1975; Australian Government, 2009). Poverty analysis of Indigenous Australians has long been held back by the fact that their historical circumstances are so different from those of other people that the use of the standard toolkit of poverty researchers has been manifestly inadequate (Altman & Hunter, 1998). For example, Indigenous people live in households that are very large and socially complex – that is, Indigenous households tend to be multi-family, multi-generational and highly fluid (or even ‘porous’), so that the size and composition of the household is not necessarily well defined. Many Indigenous Australians live in remote and regional areas where prices are substantially higher than in urban Australia,1 while customary activities in those areas (such as hunting and gathering) can provide considerable sustenance and resources that are not transacted in the market.2 One crucial problem for poverty studies is that the equivalence scales used to control for differences in the size, composition and characteristics of households are often based on non-Indigenous or non-Australian studies that are most likely culturally inappropriate (e.g. Henderson, 1975).

Like poverty, FS is often associated with inadequate financial resources relative to household need, and the problems of constructing valid comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are considerable. The lack of reliable measures of income and expenditure for Indigenous Australians means that there are limited options for identifying distinct Indigenous-specific needs with respect to financial and other resources (Hunter et al., 2003, 2004). Fortunately, there are several large-scale datasets with reliable and comparable data on FS for both Indigenous and other Australians. Hence it should be possible to identify the Indigenous-specific factors underlying FS in Australia. This paper uses the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) and wave 14 of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, collected at a similar time period, to examine whether the processes underlying Indigenous financial stress are different than among other Australians.

We use these models of FS to produce equivalence scales. Equivalence scales can be thought of as an index for a particular household type that equates the income required to achieve the same utility or welfare as a reference household (say, two adults and no children). Food expenditure is often used to create equivalence scales as the share of food expenditure in total consumption has been found to be monotonically decreasing in income (see Deaton & Muellbauer, 1980).3 If we believe that utility is increasing in income, then any necessity that has a monotonic relationship with income can be used to create an equivalence scale. In our particular case, we can think of the equivalence scale as telling us about the amount of additional income required to achieve the same probability of experiencing FS. Inasmuch as FS is a good proxy for underlying utility, the equivalence scale will have this additional interpretation.

This approach allows us to compare Indigenous-specific equivalence scales to those constructed for other Australians or other populations using the same methodology. This will help us to determine whether an alternative treatment of equivalence scales is warranted for Indigenous Australians. Hunter et al. (2004) show how poverty measurement among Indigenous Australians is quite sensitive to the choice of equivalence scale. The significance of this paper is that equivalence scales are commonly employed in public policy analysis, especially with respect to the design and implementation of tax and transfer policies. Hitherto there has been a dearth of literature on the relevant equivalence scales to be applied to Australia's Indigenous population when formulating such policies.

We find substantial financial stress among Indigenous Australians. We find that the determinants of FS for Indigenous Australians are similar to those for non-Indigenous Australians. However, the equivalence scales that we derive are quite different for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous households require more financial resources to avoid cashflow problems than non-Indigenous households with similar characteristics. However, Indigenous households, particularly in remote areas, generally require fewer financial resources to avoid cashflow problems than non-Indigenous households with similar characteristics. Indigenous Australians do better as household size increases in that the amount of additional income they need as household size grows to remain at a similar level of FS is lower. Finally, having lent a key card to someone else is highly associated with the experience of FS.

Overall, these results add to our contextual knowledge of Indigenous financial stress. That Indigenous households, particularly in remote areas, are able to avoid hardship with fewer resources may be linked to traditional food gathering activities. Indigenous households are also likely to have better coping mechanisms in managing large, fluid households. However. demand sharing, or ‘humbugging’, appears to create FS for those who are targeted.

The next section provides some further background to the issues and the approach taken in this paper. This is followed by an overview of the data. Financial stress is modelled using standard econometric techniques and the estimates are used to calculate equivalence scales for different sub-populations. The concluding section briefly elaborates on the implications of the findings for policy-makers and researchers.

2 Background

Neoclassical economic models are based on households making consumption decisions within budget constraints so as to maximise their utility. Financial stress can occur in two ways: as a result of an inadequate household budget (i.e. income poverty) or where a household considers that the ‘household stress’ has a lower disutility than alternative patterns of behaviour and consumption. Bray (2001) argues that some outcomes may look like ‘hardship’, but are really a rational decision by an individual who weighs up anticipated costs and benefits of various options. When analysing a subpopulation like Indigenous Australians, it is important also to consider that some consumption choices may be linked to social or cultural norms.

Financial stress represents the strain in a household associated with either a lack of financial resources or an inability to manage the available resources. FS can be associated with an inability to manage a debt burden effectively or even the lack of access to appropriate financial infrastructure, rather than indicating a lack of income or material deprivation. Bray (2001) and Breunig and Cobb-Clark (2005) have argued that such considerations mean that it is essential to distinguish between the various forms of FS – especially financial hardship and cashflow problems.

Financial stress is one probable consequence of a prolonged experience of poverty. While this paper is motivated by the inadequacies of the existing literature on Indigenous poverty, there is a clear conceptual distinction between FS and poverty, even though there is some scope for overlap. In modelling FS, it is important to attempt to control for factors that are associated with debt burden and access to financial infrastructure, so that some inference can be made about the factors that are more likely to be associated with poverty per se.

One motivation for this paper is to empirically model the processes underlying FS of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Two specifications of FS are considered: a parsimonious specification that allows comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and a richer specification that controls for additional factors (complicated household structures, demand sharing and remoteness) that are likely to be particularly important in the Indigenous context. Indigenous customary activities in remote areas, such as living on homelands and hunting and gathering activities, may reduce the FS of households. On the other hand, remoteness may contribute to increasing FS through a higher cost of economic activity. A related issue is that household income and household size – the two most important factors that determine equivalence scales – may interact with other variables to influence household FS. Therefore, in our analysis, we control for these factors, including their interaction with household income and size.

While the more extensive specification may provide a better description of the data, we may prefer a simpler model for generating equivalence scales. Equivalence scales are often generated from simple models (see, for example, Deaton & Muellbauer, 1980) which are driven by correlation between income and food expenditure. They are not based on causally identified models. If the relationship between income and unobservables changes, then the equivalence scales change. This further highlights the need for context-specific equivalence scales. With that in mind, several expanded specifications are used here in an attempt to better understand how the processes underlying FS and poverty in Indigenous and other populations might differ substantially.

A significant number of previous studies (Bray, 2001; Breunig & Cobb-Clark, 2005; La Cava & Simon, 2005; Marks, 2007; Yates, 2007; Cobb-Clark & Ribar, 2012; Phillips & Nepal, 2012; Ryan, 2012; Read et al., 2014) have attempted to identify the determinants of FS in Australian households. These studies typically find household income to be the most important variable associated with FS. It is a strong empirical regularity that FS falls as household income rises. In contrast, given household income, research typically finds a positive relationship between household size and FS. In other words, as household size increases so does FS. Not surprisingly, wealthier households have a better capacity to manage FS as resources can be mobilised in case of a negative financial event. In the same way, households may enjoy a lower FS if their accommodation is owned, compared to rented.4

A variety of other variables have also been found to be related to financial stress. The relationship status of household members may affect FS. Couple-headed households (either married or de facto partnerships) may enjoy the advantage of simultaneously working in complementary home and market activities and may also substitute for one another in either of these activities when needed. The presence of children, by increasing costs and perhaps by exacerbating financial management, seems to increase the FS of households. Indeed, Breunig and Cobb-Clark (2005), using Australian data, find that households with children are much more likely than households without children to suffer from FS (as measured by financial hardship). Cobb-Clark and Ribar (2012) find that FS and borrowing constraints are related to earlier periods of economic inactivity. Multi-family households may be different than other households and may act differently when they encounter a financially stressful event. Finally, a family member's disability, including the type of disability, may also increase the FS of households by increasing their demand for resources. Ryan (2012) finds that age, employment and household income are positively associated with financial well-being, while individuals with long-term health conditions report lower levels of financial well-being. Becoming a single parent and separating from a spouse have a negative effect on financial well-being. Phillips and Nepal (2012) find that, even independent of income, employment status matters. Unemployed households suffer from a much higher rate of FS than their employed counterparts.

A large strain of the literature has focused on the relationship between expenditure on housing (or ‘mortgage stress’) and overall financial stress. Yates (2007) finds that spending a higher proportion of income on housing may increase the incidence of FS. La Cava and Simon (2005) find that the probability of a household being financially constrained is significantly affected by age, home ownership, income, and the income share of mortgage repayments. Read et al. (2014) find that households with relatively high debt-servicing ratios are more likely to miss mortgage payments.

Marks (2007) is the only other paper that we are aware of that has looked specifically at Indigenous households and financial stress. He finds that Indigenous status is strongly associated with increased odds of being in subjective poverty and FS. However, in his study, the contribution of Indigenous status disappears when education and marital status are taken into account. There is a large literature on Indigenous poverty and disadvantage. Hall and Patrinos (2012) show that Indigenous people are often the poorest of the poor in terms of income. Kowal et al. (2007) demonstrate the widespread socioeconomic and health disadvantages experienced by Indigenous Australians. Kendall (2001) shows that the level of socio-economic outcomes for Aboriginal Canadians resembles those of poor people in developing countries more than for non-aboriginal Canadians. The Canadian literature is quite extensive. The paper by Power (2008) is noteworthy as she shows that conceptualisations of food security that were developed in non-Aboriginal contexts perform poorly in Aboriginal contexts. There are unique food security considerations for Aboriginal people related to harvesting, sharing of country and consumption of traditional foods. Our results point to something similar in Australia with respect to FS.5

Breunig and Cobb-Clark (2005) outline a model of financial stress that may allow us to make some inferences about how ‘poverty’ broadly defined is measured using equivalence scales. Their approach is to parsimoniously model the factors that determine household FS. Using a probit model, they control for determinants such as income, household size, children, geographic location and home ownership. Then they compute equivalence scales by solving for the amount of household income that produces equivalent levels of FS for different household types. While we consider different variables, our approach to building equivalence scales follows theirs.

In this paper, we make several contributions to the literature. We estimate a model of FS specifically for Indigenous Australians and compare those results to non-Indigenous Australians using a large sample of Indigenous households. The behaviour of Indigenous households cannot be assumed to be the same as that of non-Indigenous Australians, so having Indigenous-specific estimates is important. Importantly, we also consider an expanded definition of FS which includes items that are potentially better able to capture the unique nature of FS for Indigenous households. We use our models to build equivalence scales for Indigenous and non-Indigenous households which can be used to think about what types of changes in characteristics or policies would be required to equalise the probability of experiencing FS across these different types of households. We examine to what degree FS is about differences in characteristics and to what degree it is about a different relationship between characteristics and FS for Indigenous and non-Indigenous households. We find that both matter. Our approach provides important insight into the experience and context of FS in Indigenous Australia and into the role of remoteness and the ability of Indigenous households to cope with large, fluid households.

We next turn to describing the two data sets that we use.

3 Data

We use the HILDA Survey, a nationally representative panel survey of Australian households which, since 2001, has collected data related to financial, socioeconomic and financial stress issues. HILDA is recognised as a good source of data about FS. While Indigenous Australians are slightly over-represented in HILDA relative to the population, the sample of Indigenous Australians is still small (Table 1).

| Household type | Freq. | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No member of Indigenous origin | 9,266 | 97.15 |

| Members includes Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | 272 | 2.85 |

| Total | 9,538 | 100.00 |

Note

- The Indigenous population is slightly over-represented in the sample.

We use HILDA to study non-Indigenous Australians. In our analysis, we create a non-Indigenous sub-sample by dropping the 272 wave 14 households which contain at least one individual who self-identifies as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

To study Indigenous Australians, we use the 2014–15 NATSISS. This survey is a useful source of information about Indigenous Australians on a range of demographic, social, environmental and economic issues, including FS. The survey allows us to conduct analysis on the FS of Indigenous Australians using a large, Indigenous-specific sample and to compare those results to analysis of FS on non-Indigenous Australians. The 2014–15 NATSISS and wave 14 of HILDA include similar questions on FS and collect a similar set of socioeconomic data. Also, both are collected through face-to-face interviews.6 Furthermore, the surveys were conducted at a similar time.7 As a result, the data can be used to examine differences in FS between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations without confounding macroeconomic or survey mode effects.

In our paper we follow Breunig and Cobb-Clark (2005) and conduct three indicator (0–1) measures of FS which we have labelled ‘cashflow’, ‘hardship’ and ‘any financial stress’. In HILDA, respondents over the age of 15 are asked to fill out a self-completion questionnaire (SCQ). They are asked whether or not, over the last 12 months, any of the following happened to them because of a shortage of money: inability to pay bills on time; inability to pay the mortgage or rent on time; pawning or selling something; asking for financial help from family or friends; asking for help from welfare or community organisations; an inability to heat the home; and missing meals. The ‘cashflow’ variable is coded as 1 if respondents indicated that they had cashflow problems (inability to pay rent/mortgage; inability to pay utilities; and borrowing from friends). The ‘hardship’ variable is coded as 1 if respondents experienced financial hardship (as measured by missing meals, pawning something, inability to heat the home and applying for welfare). The ‘any stress’ variable is equal to 1 if the individual responded in the affirmative to at least one of the FS indicators in the questionnaire.

For NATSISS, we constructed analogous measures of FS relying on the response categories that were similar to HILDA.8 The NATSISS data include some additional FS-related variables such as short-term loans, inability to pay car registration or insurance, inability to make the minimum repayment on a credit card and a few other items (see Appendix A). Using these additional data, we construct an ‘extended NATSISS’ financial stress indicator variable.9 Cashflow difficulties are extended to include inability to pay for car registration or insurance, inability to make the minimum credit card repayment or taking out a short-term loan because you did not have enough money. Hardship difficulties are extended to include a household member having lived without basic living items in the last 12 months.

In the NATSISS data there is also a question about whether you gave someone else access to your key card. We include this variable in all FS regressions. It could be one way to detect the presence of ‘humbugging’/demand sharing and its relationship to FS.

For our non-Indigenous sample, we want to focus on non-remote families living in single-family households. Remoteness is rare in HILDA (about 1 per cent of households) since the sample was originally chosen from a frame that excluded remote households. Only households that subsequently moved to remote areas appear in HILDA. Multi-family households are also fairly rare: again, just over 1 per cent of households have more than one family living together in them. For our non-Indigenous/HILDA sample we exclude these two groups. We also drop 1,525 observations where either FS or one of the independent variables in our model is missing. The vast majority of these deletions are caused by missing FS. The SCQ has a lower response rate than the main questionnaire and since FS is asked in the SCQ, we lose many observations from failure to return/answer the SCQ. As indicated above, we drop all households that have at least one Indigenous member. We drop 125 households in remote areas and 103 multi-family households. Our final sample size for HILDA is 7,600.

Remoteness and multi-family households are much more common in Indigenous households. One way that we will explore the role of remoteness and multi-family households in FS is by comparing a NATSISS sub-sample with the same exclusions as our HILDA sample to the full NATSISS data which include remote and multi-family households.

For this sub-sample, we drop remote and multi-family households from NATSISS.10 Starting with 6,611 observations, we exclude 1,494 observations which contain missing values for FS or any of the independent variables. We further drop 2,091 remote and 184 multi-family households to get our analysis sample of size 2,842.11 Summary statistics of the baseline definition of FS (based upon those variables available in both data sets) are presented for the HILDA sample, the non-remote/non-multi-family NATSISS sample and the full NATSISS sample in columns 1–3 of Table 2, respectively. Columns 4 and 5 show average levels of FS based upon the extended definition using the additional questions available in NATSISS.

| NATSISS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparable (with HILDA) definition of FS | Extended NATSISS definition of FS | ||||

| HILDA | Non-remote and non-multi-family | Full sample | Non-remote and non-multi-family | Full sample | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Cashflow | 0.179 | 0.396 | 0.393 | 0.504 | 0.496 |

| (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| Hardship | 0.096 | 0.189 | 0.182 | 0.276 | 0.269 |

| (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.006) | |

| Any stress | 0.207 | 0.430 | 0.426 | 0.512 | 0.505 |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| N | 7,600 | 2,842 | 5,117 | 2,842 | 5,117 |

Notes

- The ‘comparable (with HILDA) definition’ uses the same definitions as HILDA while the ‘extended NATSISS definition’ uses an extended definition of FS, based on information available only in the NATSISS data. Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are estimated using jackknife replicate weights.

Comparison between the columns shows that, compared to non-Indigenous households, Indigenous households suffer from a significantly higher incidence of FS. Comparing columns 1 and 2, we can see that for non-remote, non-multi-family households, Indigenous Australians are roughly twice as likely to report FS as non-Indigenous households. These differences are statistically significant. When we look at the Indigenous sample which includes remote households and multi-family households, we actually see slightly lower FS (compared to non-remote and non-multi-family Indigenous households). Remoteness and multi-family households may offer some protective advantages. Those living in their country in remote areas may be able to resort to traditional hunting and gathering practices to stave off FS. Multi-family households may offer more opportunity for resource sharing and provide insurance for household members. A similar pattern holds for both our limited and extended definitions of FS.

Overall, the consistently higher incidence of FS for Indigenous Australians indicates the importance of Indigenous-specific factors underlying their FS, as indicated in Hunter et al. (2004).

If we compare levels of FS using the limited and extended versions, we find about 10 percentage point higher levels of financial difficulty using the extended measure. By this measure, almost half of Indigenous households experienced FS at some point during the year. In all cases, cashflow problems are about twice as prevalent as hardship difficulties.

Like previous studies, we find financial stress measures to have a negative association with household income (Table 3). Financial stress generally has a positive association with household size, with the exception of single households (Table 4). This pattern reflects the advantages that couple-headed households enjoy (discussed above) as well as the much lower average incomes of singles. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the importance of including income and household size in models of FS and controlling for both of these factors simultaneously.

| HILDA income quintiles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 & 5 | |

| HILDA | ||||

| Cashflow | 0.229 | 0.245 | 0.203 | 0.109 |

| (0.013) | (0.017) | (0.013) | (0.008) | |

| Hardship | 0.184 | 0.139 | 0.094 | 0.032 |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.004) | |

| Any stress | 0.288 | 0.272 | 0.231 | 0.122 |

| (0.013) | (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.008) | |

| NATSISS Non-remote and non-multi-family households (with comparable (with HILDA) definition of FS) | ||||

| Cashflow | 0.473 | 0.450 | 0.341 | 0.204 |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.019) | |

| Hardship | 0.290 | 0.212 | 0.115 | 0.025 |

| (0.014) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.007) | |

| Any stress | 0.519 | 0.486 | 0.373 | 0.214 |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

| NATSISS Non-remote and non-multi-family households (with extended NATSISS definition of FS) | ||||

| Cashflow (extended) | 0.606 | 0.543 | 0.432 | 0.304 |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| Hardship (extended) | 0.396 | 0.303 | 0.170 | 0.098 |

| (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.014) | |

| Any stress (extended) | 0.613 | 0.556 | 0.442 | 0.304 |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| NATSISS full sample (with extended NATSISS definition of FS) | ||||

| Cashflow (extended) | 0.592 | 0.531 | 0.435 | 0.311 |

| (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| Hardship (extended) | 0.372 | 0.295 | 0.176 | 0.119 |

| (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

| Any stress (extended) | 0.602 | 0.543 | 0.445 | 0.312 |

| (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

Notes

- NATSISS means are generated using income quintiles of HILDA to make them comparable with non-Indigenous Australians. Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are estimated using jackknife replicate weights.

| Household size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6+ | |

| HILDA | ||||||

| Cashflow | 0.188 | 0.140 | 0.206 | 0.185 | 0.208 | 0.289 |

| (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.015) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.035) | |

| Hardship | 0.131 | 0.069 | 0.100 | 0.081 | 0.092 | 0.212 |

| (0.009) | (0.005) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.017) | (0.074) | |

| Any stress | 0.229 | 0.165 | 0.232 | 0.200 | 0.219 | 0.377 |

| (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.065) | |

| NATSISS Non-remote and non-multi-family households (with comparable (with HILDA) definition of FS) | ||||||

| Cashflow | 0.394 | 0.298 | 0.435 | 0.443 | 0.453 | 0.531 |

| (0.020) | (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.030) | (0.040) | |

| Hardship | 0.283 | 0.153 | 0.154 | 0.170 | 0.184 | 0.230 |

| (0.018) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.018) | (0.024) | (0.033) | |

| Any stress | 0.445 | 0.323 | 0.458 | 0.472 | 0.498 | 0.593 |

| (0.020) | (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.031) | (0.039) | |

| NATSISS Non-remote and non-multi-family households (with extended NATSISS definition of FS) | ||||||

| Cashflow (extended) | 0.551 | 0.418 | 0.524 | 0.484 | 0.547 | 0.678 |

| (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.030) | (0.037) | |

| Hardship (extended) | 0.367 | 0.240 | 0.253 | 0.262 | 0.225 | 0.345 |

| (0.020) | (0.015) | (0.019) | (0.021) | (0.026) | (0.038) | |

| Any stress (extended) | 0.556 | 0.423 | 0.531 | 0.500 | 0.559 | 0.688 |

| (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.030) | (0.037) | |

| NATSISS full sample (with extended NATSISS definition of FS) | ||||||

| Cashflow (extended) | 0.530 | 0.416 | 0.530 | 0.485 | 0.522 | 0.615 |

| (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

| Hardship (extended) | 0.346 | 0.232 | 0.277 | 0.254 | 0.219 | 0.299 |

| (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.017) | (0.019) | |

| Any stress (extended) | 0.539 | 0.422 | 0.538 | 0.499 | 0.536 | 0.621 |

| (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

Note

- Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are estimated using jackknife replicate weights.

Summary statistics for the independent variables which we use in our analysis are presented in Table 5. A comparison of columns 1 and 2 highlights the differences in household characteristics between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The most important difference is the substantially lower income of Indigenous households. In the HILDA sample the average weekly income is $2,042 in 2014. In the full NATSIS sample it is $1,292, or a gap of $750. The data also show important differences in household size, number of children and home ownership. Household size is 10 per cent larger in the full NATSISS sample than in the HILDA sample, and the difference is statistically significant. Indigenous households have more children and consequently larger size. In the HILDA data, 68 per cent of respondents either own or are purchasing their home. In the full NATSISS data the corresponding share is 29 per cent. HILDA households are much more likely to be partnered: 64 per cent compared to 46 per cent in the full NATSISS sample. It is likely that all these factors contribute to higher FS of Indigenous households. Reported disability is slightly higher in the non-Indigenous sample.

| NATSISS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HILDA | Excluding remote and multi-family households | Full sample | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Weekly income | 2,042 | 1,275 | 1,292 |

| (30) | (18) | (14) | |

| Household size | 2.640 | 2.838 | 2.918 |

| (0.016) | (0.027) | (0.021) | |

| Household with children | 0.264 | 0.478 | 0.468 |

| (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| Number of children | 0.472 | 0.948 | 0.934 |

| (0.009) | (0.023) | (0.017) | |

| Owner without a mortgage | 0.337 | 0.094 | 0.091 |

| (0.008) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| Owner with a mortgage | 0.343 | 0.218 | 0.197 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.006) | |

| Partnered | 0.637 | 0.483 | 0.460 |

| (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| Disabled member | 0.376 | 0.353 | 0.339 |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| Household has a non-Indigenous member | na | 0.548 | 0.507 |

| (0.009) | (0.007) | ||

| Gave someone else access to key card | na | 0.039 | 0.040 |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | ||

| Multi-family households | na | na | 0.079 |

| (0.004) | |||

| Remote household | na | na | 0.159 |

| (0.005) | |||

Notes

- ‘Weekly income’ refers to weekly household income of. Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are estimated using jackknife replicate weights provided with the HILDA data.

Column 3 shows that 16 per cent of households are in remote areas and 7.9 per cent of households contain more than one family in the full NATSISS data. Half of all Indigenous households have at least one non-Indigenous member.

Next we turn to our models of the determinants of FS and the simple model we use to construct equivalence scales.

4 Financial Stress and Equivalence Scales

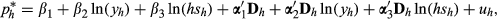

(1)

(1)We use logistic regression to estimate Equation 1. Alternative functional forms provide similar results (probit or linear probability model); we only report the marginal effects from the logistic regression model. Marginal effects are calculated as the derivative of the probability expression from the logit distribution with respect to the variable of interest for continuous variables. For discrete variables, the probability is evaluated at 1 and 0 and the difference is calculated. In both cases we set the other variables equal to their mean values.13

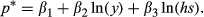

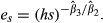

(2)

(2) (3)

(3)5 Results

We have separately identified the determinants of FS for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians using the NATSISS and HILDA data. Table 6 presents the marginal effects from the logistic regressions (from Equation 1) for the measures of financial stress defined earlier.14 Financial stress is negatively affected by household income and positively related to household size for all FS measures and all population subgroups.

| HILDA | NATSISS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(income) | −0.109*** | −0.072*** | −0.132*** | −0.097*** | −0.097*** | −0.112*** |

| (0.009) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.019) | (0.014) | (0.019) | |

| Log(household size) | 0.102*** | 0.057*** | 0.108***0.122*** | 0.029 | 0.145*** | |

| (0.016) | (0.010) | (0.017) | (0.036) | (0.026) | (0.037) | |

| Owner without a mortgage | −0.235*** | −0.101*** | −0.263*** | −0.304*** | −0.132*** | −0.323*** |

| (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.023) | (0.015) | (0.024) | |

| Owner with a mortgage | −0.076*** | −0.032*** | −0.087*** | −0.139*** | −0.104*** | −0.153*** |

| (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.025) | (0.015) | (0.026) | |

| Household with children | 0.091*** | 0.028* | 0.104*** | 0.099*** | 0.037 | 0.090*** |

| (0.026) | (0.016) | (0.029) | (0.032) | (0.023) | (0.033) | |

| Partnered | −0.081*** | −0.071*** | −0.094*** | −0.116*** | −0.060*** | −0.134*** |

| (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.015) | (0.027) | (0.019) | (0.027) | |

| Disabled member | 0.046*** | 0.052*** | 0.063*** | 0.072*** | 0.089*** | 0.092*** |

| (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.017) | (0.022) | |

| N | 7,600 | 7,600 | 7,600 | 2,842 | 2,842 | 2,842 |

Notes

- Regressions with NATSISS sample, which only include non-remote and non-multi-family households, use a definition of FS which is comparable with HILDA. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Marginal effects (using linear prediction, at the means of other covariates) are reported. For detailed coefficient results (see Table B.1). *P < 0.10, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

Home ownership and the presence of a couple are associated with lower FS. The effect of home ownership is much stronger for those who own their home outright, but there is a protective effect even for those who are still paying off a mortgage. As discussed earlier, home ownership is reflecting assets which can be used to cushion financial difficulties, and couple-headed households have advantages in organisation and within-household trading that contribute to lower FS.

The presence of children or disabled household members is associated with higher financial stress. The exception is for the hardship measure for the Indigenous sample where the effect of children is insignificant. Children and disabled individuals likely raise costs (both financial and organisational) for households without generating compensating income flows. These results overall conform to what has been found in both the Australian and international literatures.

Table 7 compares two samples of Indigenous households. We use the extended definitions of FS making use of the additional information in the NATSISS questionnaire. The first three columns of Table 7 use the non-remote and non-multi-family households from NATSISS. The last three columns estimate the model using the full NATSISS sample. In the last three columns, we include controls for multi-family households and living in a remote area.

| Excludes remote and multi-family | Full sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(income) | −0.110*** | −0.124*** | −0.120*** | −0.123*** | −0.127*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.012) | (0.014) | |

| Log(household size) | 0.137*** | 0.063* | 0.145*** | 0.147*** | 0.083*** | 0.152*** |

| (0.039) | (0.032) | (0.039) | (0.027) | (0.022) | (0.027) | |

| Owner without a mortgage | −0.372*** | −0.188*** | −0.377*** | −0.322*** | −0.173*** | −0.326*** |

| (0.025) | (0.018) | (0.026) | (0.023) | (0.015) | (0.024) | |

| Owner with a mortgage | −0.184*** | −0.120*** | −0.187*** | −0.170*** | −0.119*** | −0.171*** |

| (0.027) | (0.019) | (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.016) | (0.025) | |

| Household with children | 0.050 | 0.045* | 0.056 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.017 |

| (0.034) | (0.028) | (0.035) | (0.024) | (0.020) | (0.024) | |

| Partnered | −0.092** | −0.084*** | −0.106*** | −0.039* | −0.039** | −0.048** |

| (0.036) | (0.029) | (0.036) | (0.022) | (0.018) | (0.022) | |

| Disabled member | 0.065*** | 0.120*** | 0.073*** | 0.066*** | 0.112*** | 0.074*** |

| (0.023) | (0.020) | (0.023) | (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.017) | |

| Household has a non-Indigenous member | −0.041 | 0.006 | −0.031 | −0.086*** | −0.041** | −0.081*** |

| (0.035) | (0.028) | (0.035) | (0.023) | (0.019) | (0.024) | |

| Gave someone else access to key card | 0.558*** | 0.321*** | 0.546*** | 0.579*** | 0.291*** | 0.590*** |

| (0.097) | (0.049) | (0.098) | (0.074) | (0.035) | (0.077) | |

| Multi-family household | na | na | na | 0.046 | 0.062 | 0.053 |

| (0.047) | (0.041) | (0.047) | ||||

| Remote household | na | na | na | −0.078*** | −0.091*** | −0.078*** |

| (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.018) | ||||

Notes

- Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Marginal effects (using linear prediction, at the means of other covariates) are reported. For detailed results, see Table B.2. *P < 0.10, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

The results are broadly similar across the two samples. Interestingly, living in a multi-family household is associated with higher FS (though not statistically significant). A priori, it is not clear what association we would expect to find. Multi-family households provide an additional insurance mechanism against financial difficulties, but they also provide more opportunity for ‘humbugging’. Our best proxy measure of ‘humbugging’, whether you gave someone else access to your key card, is highly correlated with FS.

Living in a remote area is associated with lower FS, once we control for income. This could be evidence that traditional country food, hunting and gathering and other customary activities could be helping Indigenous people to alleviate FS. This corresponds to anecdotal reports that such activities lead to lower difficulties with FS.15

The other covariates generally provide the same picture as the analysis of Table 6. Home ownership is related to lower FS, and the effect is stronger if the home is paid off. Again, this is consistent with assets helping to offset financial problems that might arise and preventing them from becoming financially stressful episodes. Having given someone else access to your key card is positive and strongly statistically significant. This could be evidence for a negative effect of ‘humbugging’ on people's financial situations.

Table 8 compares the results from these models by asking the following two questions. If we consider two households with identical characteristics, what do the different models predict in terms of expected probability of FS? How much income would we need to give to or take away from the Indigenous households to make their probability of FS equivalent to that of the non-Indigenous households from HILDA?

| Source | Sample | Model | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HILDA | Table 6, cols 1–3 | 0.191 | 0.058 | 0.208 | |

| NATSISS | Non-remote and non-multi family | Table 6, cols 4–6 | 0.219 | 0.021 | 0.220 |

| [$2,440] | [$1,075] | [$2,200] | |||

| NATSISS | Non-remote and non-multi family | Table 7, cols 1–3 | 0.311 | 0.061 | 0.304 |

| [$5,580] | [$2,140] | [$4,240] | |||

| NATSISS | Full sample (remote = 0) | Table 7, cols 4–6 | 0.377 | 0.079 | 0.371 |

| [$21,320] | [$2,985] | [$13,100] | |||

| NATSISS | Full sample (remote = 1) | Table 7, cols 4–6 | 0.290 | 0.045 | 0.282 |

| [$5,270] | [$1,490] | [$3,955] |

Notes

- The reference household is a single-family, couple-headed household with two children, paying off a mortgage, no disability. We assign the average weekly income from HILDA to the household: $2,042 We exclude remote and multi-family households from the HILDA sample. The estimates of probability of financial stress in row 1 (the HILDA sample) form the basis for calculating the required amount of income to achieve equal probability of experiencing financial stress.

As a reference household, we take a couple-headed household with two children who are paying off a mortgage and have no disability. We assign the average weekly income from HILDA ($2,042) and we predict the probability of FS from the estimated model of Table 6. This is presented in the first row of Table 8 and labelled ‘HILDA’. In the following rows, we present the estimated probability of financial stress at the same covariate values using the NATSISS sample with a similar FS definition to HILDA, the NATSISS sample with the extended FS definition but excluding remote and multi-family households, and finally for the full NATSISS sample. For the full NATSISS sample comparisons (the last two rows), we set ‘access to key card’, ‘non-Indigenous household members’ and ‘multi-family households’ equal to zero. We consider both non-remote and remote households (in the second last row, we keep remote set to zero and in the last row we change remote to equal 1 to generate the predicted probabilities).

At this common set of covariate values, Indigenous households experience more ‘cashflow’ FS than non-Indigenous households for all measures and samples. In order to be at the same level of FS, they would need between $398 and $19,278 of extra weekly income, depending upon the model. The very large amount of additional income required for a non-remote Indigenous household to achieve the same probability of experiencing FS as a non-Indigenous household reflects both the large difference in underlying probability of experiencing FS and the relatively small gradient of FS with respect to income. It takes large amounts of extra income to change the probability of experiencing cashflow FS by a substantial amount.

Using a common definition to HILDA, Indigenous households are less likely to experience ‘hardship’ FS than non-Indigenous households. Remote Indigenous households are also less likely to experience ‘hardship’ FS than non-Indigenous households when we use the extended FS definition from the NATSISS. Non-remote, non-multi-family Indigenous households experience ‘hardship’ at approximately the same level as non-remote Indigenous households using the extended FS definition. When we consider non-remote Indigenous households, but using the full sample which includes multi-family households, we find a slightly larger probability of experiencing FS than for non-Indigenous households with the same household characteristics.

In summary, Indigenous households with similar characteristics to non-Indigenous households are more likely to experience ‘cashflow’ FS. But Indigenous households are about as likely as non-Indigenous households to experience ‘hardship’ FS when we restrict the sample to make the set of Indigenous and non-Indigenous households similar. When we consider remote Indigenous households, they are substantially less likely to experience ‘hardship’ FS than non-remote, non-Indigenous Australians with the same level of income and household characteristics.16

We estimate Equation 2 and form equivalent scales following Equation 3. In Table 9, we present equivalence scales for non-Indigenous households (using the HILDA data).17 We can see from Table 9 that the amount of money required to equalise the probability of FS as household size grows is much larger than the amount required to equalise consumption. This is perhaps not surprising. FS is not just about consumption but about management and organisation. These are probably correlated with income. Thus, it seems that it takes a substantial amount of resources to offset these factors for households experiencing FS. It could also be that FS goes beyond simple consumption needs and that, as households grow, consumption desires become more complicated and fulfilling them creates more possibility of FS.

| Household size | OECD equivalence scale | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.49 | 2.16 | 1.69 | 1.92 |

| 3 | 1.89 | 3.40 | 2.29 | 2.80 |

| 4 | 2.25 | 4.68 | 2.85 | 3.67 |

| 5 | 2.63 | 5.99 | 3.37 | 4.52 |

| 6 | 2.96 | 7.34 | 3.87 | 5.37 |

Tables 10 and 11 present results for Indigenous Australians, in Table 10 with the NATSISS sample that is comparable to HILDA and in Table 11 for the full NATSISS sample. We use the extended FS measures described above. Equivalence scales for Indigenous households increases much more slowly with household size than for non-Indigenous Australians.

| Household size | OECD equivalence scale | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.45 | 1.67 | 1.41 | 1.68 |

| 3 | 1.82 | 2.26 | 1.73 | 2.27 |

| 4 | 2.15 | 2.80 | 1.99 | 2.82 |

| 5 | 2.47 | 3.31 | 2.23 | 3.33 |

| 6 | 2.73 | 3.79 | 2.44 | 3.82 |

| Household size | OECD equivalence scale | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.46 | 1.72 | 1.34 | 1.70 |

| 3 | 1.83 | 2.37 | 1.59 | 2.33 |

| 4 | 2.18 | 2.97 | 1.80 | 2.90 |

| 5 | 2.53 | 3.54 | 1.97 | 3.45 |

| 6 | 2.83 | 4.08 | 2.13 | 3.97 |

There are several reasons why this might be the case. It could be that Indigenous households are more experienced at managing large, fluid households. As household size grows, they are able to cope with fewer resources. It could also be that money income is less important in alleviating FS as household size grows for Indigenous Australians. They can perhaps turn to other activities such as hunting and gathering to help offset financial stress.

It could also be driven by a different sense of what constitutes FS for Indigenous and non-Indigenous households. However, we do see much higher reports of FS amongst Indigenous households. Nonetheless, there could be systematic differences in what the two groups assess as FS.

In Tables 12–14 we consider some special cases of equivalence scales for more complicated household comparisons. The tables consider cashflow, hardship and any difficulty, respectively, and use the extended FS definition from NATSISS.

| Household | Reference | Disabled | Non-Indigenous | Remote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | household | member | member | household |

| (a) Relative to reference household of size 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.16 | 1.44 | 0.95 | 1.32 |

| 2** | 2.43 | 3.85 | 1.31 | 2.11 |

| 3 | 2.48 | 3.88 | 1.88 | 2.38 |

| 4 | 3.08 | 5.39 | 2.58 | 2.94 |

| 5 | 3.59 | 6.85 | 3.32 | 3.44 |

| 6 | 4.19 | 8.57 | 4.06 | 3.94 |

| (b) Relative to same-sized reference household | ||||

| 1 | 2.02 | na | 0.49 | |

| 2 | 2.83 | 0.62 | 0.46 | |

| 3 | 3.21 | 0.79 | 0.49 | |

| 4 | 3.59 | 0.92 | 0.50 | |

| 5 | 3.78 | 1.10 | 0.53 | |

| 6 | 3.92 | 1.25 | 0.55 | |

Note

- Reference households are not home owners, non-multi-family. Households with two or more people are couple-headed except where indicated. Households with three or more people have children present. *Includes remote and multi-family household and use extended financial stress definition. **Two individuals in household but not couple-headed.

| Household size | Reference | Disabled | Non-Indigenous | Remote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| household | member | member | household | |

| (a) Relative to reference household of size 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.20 | 1.51 | 0.90 | 1.14 |

| 2** | 1.57 | 2.22 | 1.08 | 1.47 |

| 3 | 1.37 | 2.26 | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| 4 | 1.37 | 2.45 | 1.50 | 1.20 |

| 5 | 1.35 | 2.57 | 1.73 | 1.20 |

| 6 | 1.34 | 2.70 | 1.95 | 1.16 |

| (b) Relative to same sized reference household | ||||

| 1 | 2.11 | na | 0.55 | |

| 2 | 3.21 | 0.63 | 0.51 | |

| 3 | 3.70 | 0.78 | 0.49 | |

| 4 | 4.13 | 0.89 | 0.48 | |

| 5 | 4.34 | 1.02 | 0.47 | |

| 6 | 4.54 | 1.12 | 0.47 | |

Notes

- Reference households are not home owners, non-multi-family. Households with two or more people are couple-headed except where indicated. Households with three or more people have children present. *Includes remote and multi-family household and use extended financial stress definition. **Two individuals in household but not couple-headed.

| Household size | Reference | Disabled | Non-Indigenous | Remote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| household | member | member | household | |

| (a) Relative to reference household of size 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.04 | 1.35 | 0.67 | 1.21 |

| 2** | 2.45 | 3.34 | 0.98 | 2.05 |

| 3 | 2.47 | 3.68 | 1.38 | 2.26 |

| 4 | 3.08 | 5.10 | 1.89 | 2.77 |

| 5 | 3.68 | 6.59 | 2.41 | 3.26 |

| 6 | 4.24 | 8.15 | 2.94 | 3.71 |

| (b) Relative to same sized reference household | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1.96 | na | 0.50 |

| 2 | 2 | 2.62 | 0.44 | 0.45 |

| 3 | 3 | 3.07 | 0.57 | 0.47 |

| 4 | 4 | 3.44 | 0.66 | 0.48 |

| 5 | 5 | 3.73 | 0.79 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 6 | 3.99 | 0.89 | 0.52 |

Notes

- Reference households are not home owners, non-multi-family. Households with two or more people are couple-headed except where indicated. Households with three or more people have children present. *Includes remote and multi-family household and use extended financial stress definition. **Two individuals in household but not couple-headed.

In Table 12a we present equivalence scales which compare different family types using the estimated model of Equation 1 (results in Table B.2) for the cashflow measure. This allows us to create equivalence scales which depend upon a greater variety of characteristics than simply household size. We construct the equivalence scale by taking the probability of experiencing FS for a reference household based upon the estimated model of Equation 1 with a particular level of income and solving for the amount of income that a comparison household would require to achieve the same propensity to experience FS.

We use a single-individual household with average income (for single individuals) from the data as the reference one-person household. We consider two-person households that are couple-headed and two-person households where the two individuals are not partners (row 3, flagged as **.) We treat all households of size 3 or larger as couple-headed and as having children present. These are the most common values in the data.

For all households, we begin by considering households that are not home owners or buyers, that have no disabled members, that have no non-Indigenous members and that contain only one family. Looking at column 2 of Table 12, we can see that these produce a slightly smaller gradient of household income as household size increases. This reflects the fact that couple-headedness confers advantages in avoiding financial stress. (Table 11 averages across couple-headed and non-couple-headed households and thus produces steeper equivalence scales.) In row 3, when we consider a two-person household that is not couple-headed (but in which there are no children) we see that the equivalence scale is substantially higher.

In columns 3–5 of Table 12a, we examine additional characteristics that we consider one by one in the equivalence scale estimates. In each case, we consider households of all sizes to have this characteristic. The one exception is the presence of a non-Indigenous member, where for a household of size 1, the data construction requires that this person be Indigenous since there are no entirely non-Indigenous households in our sample.

Disability, in addition to producing higher FS, also increases the gradient of the equivalence scale. This is through the interaction of disability with income and household size. Larger households need more resources, the more so when a disabled person is present in the household.

The presence of a non-Indigenous member, in contrast, greatly flattens the equivalence scale. The presence of a non-Indigenous member is highly correlated with less FS. This is consistent with anthropological evidence that the presence of non-Indigenous householders lessens financial pressures from ‘demand sharing’ (see Peterson & Taylor, 2003). So a partnered couple where one of the members is Indigenous only requires two-thirds the income of a single Indigenous individual to be at the same probability level of experiencing FS.

Remoteness lowers the probability of FS (conditional on other characteristics), and also lowers the gradient of the equivalence scale with respect to household size.

In Table 12b, we consider equivalence scales where we compare households that have a particular characteristic (disability, a non-Indigenous member, remoteness) to an otherwise identical household that does not have that characteristic.

Columns 3–5 present these results. A disabled single person requires double the income that a non-disabled single person needs to achieve the same probability of avoiding FS. For a three-person household with a disabled member, this number climbs to 321 per cent.

The presence of a non-Indigenous member results in households needing only 67–92 per cent of the income of otherwise identical households when the household has four members or fewer. As household size grows, the protection of a non-Indigenous member decreases. Remoteness also results in households needing only around half as much income to achieve an equal probability of avoiding FS.

Tables 13 and 14 provide similar results for the measures of hardship and any FS. What is striking in both panels of Table 13 is the very strong relationship between disability and hardship. The additional resources needed by families to cope with disability as household size grows are very substantial. A household with four people, for example, needs 4.13 times more money income to be at the same level of hardship propensity as a household of four with no disabled person present.

With remote households, we again find a fairly flat gradient in the equivalence scales as household size increases. Remote households need only about half as much money, at any household size, to be at the same level of hardship probability as non-remote households. This strongly highlights the coping mechanisms that remote Indigenous households employ despite their low incomes. It may also reflect fewer expenditure possibilities in remote areas.

5.1 Additional Analysis

We considered an alternative measure of FS. Instead of treating FS as a binary variable we created a continuous variable as the count of the number of FS items ticked in the list. For the HILDA data, this creates a continuous variable which takes whole values from 0 to 3 for ‘cashflow’, 0 to 4 for ‘hardship’ and 0 to 7 for ‘any stress’. In the NATSISS data, this creates a continuous variable which takes whole values from 0 to 6 for ‘cashflow’, 0 to 5 for ‘hardship’ and 0 to 11 for ‘any stress’. We re-estimate Equation 2 by ordinary least squares and create equivalence scales from this alternative FS measure. We find that the equivalence scales are nearly identical for Tables 9–11.18 This is not too surprising since the vast majority of households tick either zero or one item, so there is little additional information in this measure.

We estimate the ‘cashflow’ and ‘hardship’ models of Tables B1 and B2 jointly through bi-variate probit estimation. The marginal effects are unchanged, as are the implied equivalence scales. There is a large amount of correlation in the unobservables between the two measures. This is unsurprising since factors such as ability to manage one's money will influence reports of both.19

6 Conclusion and Discussion

There are many conceptual complexities underlying Indigenous financial stress or poverty that are not adequately captured in mainstream poverty analysis (Altman & Hunter, 1998; Hunter, 2013). A credible analysis of either phenomenon must acknowledge both the diversity of Indigenous circumstances and how distinct value systems drive preferences and behaviours that shape the ability of policy to address Indigenous disadvantage. Analysis needs to take into account, and be informed by, specific social and cultural circumstances facing Indigenous Australians.

Hunter (2013) argues that Indigenous-specific equivalence scales are required to take into account the distinct costs associated with running Indigenous households and associated FS. In this paper we estimate models of the determinants of FS and use them to estimate equivalence scales which are based upon equating the propensity to experience FS across households of different sizes and different types.

We demonstrate that while the determinants of FS are in fact quite similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, the level of FS is much higher for Indigenous households. The equivalence scales that we estimate are also quite different for Indigenous and non-Indigenous households. Indigenous households appear to have better coping strategies to avoid FS as household size increases. This is reflected in equivalence scales which increase more slowly with household size than for non-Indigenous households. This seems partially related to remoteness, which leads us to conclude that hunting and gathering and traditional food sourcing activities may be playing an important role in mitigating money income disadvantage. When we consider a ‘hardship’ definition of FS, remote Indigenous households actually experience less hardship, conditional on income, than non-Indigenous households.

When considering our results it is important to keep several caveats and limitations of the analysis in mind. First, non-response rates are high, with about 20% of individuals in both data sets failing to answer the FS questions. If non-response is related to financial literacy, then our results could understate FS. If this relationship differs across Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups, our comparison of equivalence scales for the two groups may be misleading. Finally, it is important to note that reports of FS are fundamentally subjective. Two individuals could take exactly the same action and one could consider it a part of normal life and the other could report it as FS. As in the well-being literature generally, we nonetheless think it is important to take seriously people's own reports of their situation.

Our results generally highlight the importance of taking into account the specific circumstances of Indigenous Australians. In particular, we show that equivalence scales derived for non-Indigenous groups are likely to be inadequate for analysing Indigenous households. This points to a need for further work on equivalence scales, an in particular the need for an Indigenous-specific consumption-based equivalence scale. It should be a matter of some priority to include an Indigenous identifier on future household expenditure surveys. Over-sampling of Indigenous populations may also be required to produce Indigenous-specific equivalence scales on a regular basis.

The high levels of FS among Indigenous households require a policy response. Some help may be had through better financial literacy skills which could be incorporated within the compulsory education system (e.g. secondary schools). Provision of financial infrastructure and banking services, especially if delivered in a culturally accessible and appropriate manner, could also play a role in reducing Indigenous FS (see Godinho, 2015). We know that improved employment and increased incomes are the best defence against FS. Any policy response needs rigorous quantitative evaluation supported by high-quality data.

Notes

Appendix A: Data Notes: Dependent Variables

| NATSISS 2014–15 | HILDA 2014 |

|---|---|

| 1. In the last 12 months (year) have any of these things happened to you (members of this household) because you (any of you) didn’t have enough money? (More than one response allowed) | 1. Since January 2014 did any of the following happen to you because of a shortage of money? (yes/no) |

| • Couldn’t pay electricity, gas or telephone bills on time | a. Could not pay electricity, gas or telephone bills on time |

| • Couldn’t pay mortgage or rent on time | b. Could not pay the mortgage or rent on time |

| • Pawned or sold something to get money | c. Pawned or sold something |

| • Missed meals | d. Went without meals |

| • Couldn’t heat or cool your home | e. Was unable to heat home |

| • Asked for money from friends or family | f. Asked for financial help from friends or family |

| • Asked for help from welfare or community organisations | g. Asked for help from welfare/ community organisations |

| Below here, items only available on NATSISS | |

| • Used short term loans (e.g. personal loan) | n/a |

| • Ran up a tab (book up) at the local store | |

| • Couldn’t pay car registration or insurance on time | |

| • Couldn’t pay the minimum payment on your credit card | |

| • Anything else | |

| • No/None of these | |

| • Don’t know | |

| 2. In the last <12 months/year>, how many times have <you/members of this household> <experienced difficulty/had problems> in paying bills? | |

| • Once | n/a |

| • Twice | |

| • 3–5 times | |

| • 6–9 times | |

| • 10–19 times | |

| • 20 times or more | |

| • Don’t know | |

| 3. In the last <12 months/year> were there any days when <you/members of this household> ran out of money for food, clothing or bills? (yes/no) | n/a |

| 4. Did this happen in the last two weeks? (yes/no) | n/a |

| 5. Did <you members of this household> have to go without food, clothing or put off paying bills (when <you/they> ran out of money)? (yes/no) | n/a |

Appendix B: Tables

| HILDA | NATSISS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(income) | −0.328*** | −0.600*** | −0.449*** | −0.246* | −0.544*** | −0.292** |

| (0.074) | (0.089) | (0.075) | (0.147) | (0.189) | (0.146) | |

| Log(household size) | 0.681*** | 0.829*** | 0.732*** | 0.347* | −0.21 | 0.394* |

| (0.125) | (0.151) | (0.123) | (0.205) | (0.262) | (0.204) | |

| Owner without a mortgage | −0.418 | −1.302 | −0.873 | −1.420 | −2.674 | −1.505 |

| (0.793) | (0.935) | (0.743) | (1.855) | (2.444) | (1.771) | |

| Log(income) × Owner without a mortgage | −0.224* | −0.054 | −0.152 | −0.052 | 0.192 | −0.033 |

| (0.125) | (0.150) | (0.118) | (0.0294) | (0.392) | (0.281) | |

| Log(household size) × Owner without a mortgage | 0.057 | 0.039 | 0.017 | 0.040 | −0.347 | −0.027 |

| (0.213) | (0.260) | (0.198) | (0.409) | (0.560) | (0.389) | |

| Owner with a mortgage | 2.660*** | 2.806*** | 2.373*** | 1.977 | 4.677** | 2.106* |

| (0.858) | (1.086) | (0.848) | (1.264) | (1.916) | (1.256) | |

| Log(income) × Owner with a mortgage | −0.414*** | −0.419*** | −0.375*** | −0.400** | −0.820*** | −0.421** |

| (0.123) | (0.159) | (0.121) | (0.187) | (0.295) | (0.186) | |

| Log(household size) × Owner with a mortgage | −0.299** | −0.317* | −0.298** | 0.151 | −0.079 | 0.127 |

| (0.147) | (0.190) | (0.143) | (0.231) | (0.344) | (0.228) | |

| Household with children | 4.077*** | 4.185*** | 3.788*** | 1.211 | −5.545 | 1.329 |

| (0.959) | (1.192) | (0.955) | (1.018) | (1.303) | (1.020) | |

| Log(income) × household with children | −0.465*** | −0.533*** | −0.417*** | −0.075 | 0.066 | −0.109 |

| (0.135) | (0.174) | (0.133) | (0.158) | (0.208) | (0.158) | |

| Log(household size) × household with children | −0.164 | 0.054 | −0.236 | −0.310 | 0.448 | −0.231 |

| (0.265) | (0.324) | (0.262) | (0.272) | (0.340) | (0.272) | |

| Partnered | 1.164* | 0.950 | 0.836 | 0.448 | 2.101 | −0.053 |

| (0.700) | (0.880) | (0.678) | (1.069) | (1.427) | (1.062) | |

| Log(income) × Partnered | −0.264*** | −0.274** | −0.210** | −0.226 | −0.372* | −0.154 |

| (0.102) | (0.131) | (0.099) | (0.158) | (0.216) | (0.157) | |

| Log(household size) × Partnered | 0.266 | 0.182 | 0.169 | 0.677*** | −0.054 | 0.614*** |

| (0.184) | (0.236) | (0.179) | (0.238) | (0.315) | (0.236) | |

| Disabled member | −0.708 | −0.386 | −0.418 | −0.927 | −0.948 | −0.608 |

| (0.613) | (0.734) | (0.602) | (0.986) | (1.267) | (0.985) | |

| Log(income) × Disabled member | 0.143 | 0.166 | 0.116 | 0.190 | 0.194 | 0.141 |

| (0.095) | (0.115) | (0.093) | (0.157) | (0.206) | (0.157) | |

| Log(household size) × Disabled member | −0.019 | −0.199 | −0.057 | −0.080 | 0.337 | 0.025 |

| (0.138) | (0.164) | (0.135) | (0.183) | (0.217) | (0.184) | |

| Constant | 1.199** | 2.159*** | 2.217*** | 1.106 | 2.233* | 1.534* |

| (0.491) | (0.574) | (0.494) | (0.926) | (1.167) | (0.920) | |

| N | 7,600 | 7,600 | 7,600 | 2,842 | 2,842 | 2,842 |

Note

- Regressions with NATSISS sample, which only include non-remote and non-multi-family households, use a definition of FS which is comparable with HILDA. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Logistic regression coefficients are reported. *P < 0.10, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

| Excluding remote and multi-family households | Full sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | Cashflow | Hardship | Any stress | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(income) | −0.224 | −0.659*** | −0.208 | −0.282** | −0.717*** | −0.302** |

| (0.146) | (0.174) | (0.146) | (0.117) | (0.139) | (0.118) | |

| Log(household size) | 0.285 | 0.106 | 0.281 | 0.363** | 0.475*** | 0.391** |

| (0.207) | (0.243) | (0.208) | (0.151) | (0.174) | (0.152) | |

| Owner without a mortgage | −1.943 | −4.129* | −1.636 | −1.762 | −2.995** | −1.463 |

| (1.683) | (2.223) | (1.675) | (1.173) | (1.497) | (1.175) | |

| Log(income) × Owner without a mortgage | 0.016 | 0.378 | −0.040 | 0.012 | 0.221 | −0.040 |

| (0.266) | (0.354) | (0.266) | (0.189) | (0.244) | (0.189) | |

| Log(household size) × Owner without a mortgage | −0.004 | −0.094 | 0.095 | 0.216 | 0.091 | 0.280 |

| (0.368) | (0.477) | (0.364) | (0.277) | (0.374) | (0.277) | |

| Owner with a mortgage | 0.727 | 1.367 | 0.919 | −0.439 | 0.990 | −0.131 |

| (1.234) | (1.608) | (1.238) | (1.029) | (1.333) | (1.031) | |

| Log(income) × Owner with a mortgage | −0.232 | −0.318 | −0.257 | −0.074 | −0.255 | −0.111 |

| (0.181) | (0.243) | (0.182) | (0.150) | (0.201) | (0.151) | |

| Log(household size) × Owner with a mortgage | 0.108 | 0.010 | 0.084 | 0.255 | −0.043 | 0.197 |

| (0.221) | (0.289) | (0.221) | (0.193) | (0.258) | (0.193) | |

| Household with children | 0.881 | −0.555 | 1.084 | 0.548 | −0.516 | 0.704 |

| (1.035) | (1.226) | (1.042) | (0.699) | (0.828) | (0.703) | |

| Log(income) × Household with children | −0.061 | 0.121 | −0.088 | −0.022 | 0.138 | −0.041 |

| (0.158) | (0.193) | (0.159) | (0.108) | (0.132) | (0.108) | |

| Log(household size) × Household with children | −0.297 | −0.005 | −0.290 | −0.359* | −0.423* | −0.371* |

| (0.287) | (0.327) | (0.289) | (0.189) | (0.217) | (0.190) | |

| Partnered | 0.201 | 0.611 | 0.215 | −0.147 | −0.015 | −0.452 |

| (1.223) | (1.476) | (1.229) | (0.747) | (0.888) | (0.751) | |

| Log(income) × Partnered | −0.153 | −0.177 | −0.168 | −0.036 | −0.020 | 0.004 |

| (0.183) | (0.226) | (0.184) | (0.113) | (0.138) | (0.114) | |

| Log(household size) × Partnered | 0.543* | 0.111 | 0.580* | 0.248 | −0.077 | 0.244 |

| (0.296) | (0.343) | (0.297) | (0.177) | (0.213) | (0.177) | |

| Disabled member | −0.167 | −1.153 | 0.205 | −0.210 | −0.904 | 0.073 |

| (0.977) | (1.151) | (0.985) | (0.724) | (0.827) | (0.730) | |

| Log(income) × Disabled member | 0.065 | 0.242 | 0.009 | 0.061 | 0.204 | 0.018 |

| (0.155) | (0.186) | (0.156) | (0.116) | (0.135) | (0.117) | |

| Log(household size) × Disabled member | −0.017 | 0.196 | 0.030 | 0.065 | 0.121 | 0.102 |

| (0.185) | (0.204) | (0.187) | (0.137) | (0.151) | (0.138) | |

| Household has a non-Indigenous member | 0.750 | 1.213 | 0.819 | 1.782** | 1.497 | 1.785** |

| (1.197) | (1.424) | (1.206) | (0.858) | (1.022) | (0.863) | |

| Log(income) × Household has a non-Indigenous member | −0.166 | −0.208 | −0.167 | −0.384*** | −0.344** | −0.383*** |

| (0.183) | (0.224) | (0.184) | (0.130) | (0.159) | (0.131) | |

| Log(household size) × Household has a non-Indigenous member | 0.250 | 0.281 | 0.232 | 0.512** | 0.643*** | 0.528*** |

| (0.296) | (0.331) | (0.298) | (0.201) | (0.236) | (0.202) | |

| Gave someone else access to key card | 2.244*** | 1.902*** | 2.188*** | 2.315*** | 1.670*** | 2.361*** |

| (0.391) | (0.278) | (0.391) | (0.296) | (0.195) | (0.307) | |

| Multi-family household | na | na | na | −1.660 | −2.738* | −1.561 |

| (1.357) | (1.543) | (1.364) | ||||

| Log(income) × Multi-family household | na | na | na | 0.332* | 0.478** | 0.333* |

| (0.189) | (0.221) | (0.190) | ||||

| Log(household size) × Multi-family household | na | na | na | −0.441 | −0.204 | −0.519* |

| (0.285) | (0.328) | (0.285) | ||||

| Remote household | na | na | na | 0.799 | −0.087 | 0.839 |

| (0.722) | (0.855) | (0.728) | ||||

| Log(income) × Remote household | na | na | na | −0.180 | −0.060 | −0.184 |

| (0.116) | (0.140) | (0.116) | ||||

| Log(household size) × Remote household | na | na | na | 0.128 | −0.043 | 0.109 |

| (0.137) | (0.158) | (0.138) | ||||

| Constant | 1.556* | 3.299*** | 1.479 | 1.939*** | 3.602*** | 2.084*** |

| (0.925) | (1.083) | (0.927) | (0.741) | (0.860) | (0.745) | |

Note

- Standard errors are reported in parentheses. The reported statistics are logistic regression coefficients. *P < 0.10, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.