STRATEGIES AND TACTICS IN PLATFORM URBANISM: Contested Spatial Production through Quick Delivery Platforms in Berlin and Barcelona

We are very grateful to everyone who provided feedback at different stages of our development of this article—and specifically to the organizers and commentators at multiple conferences and workshops, such as ‘KRITIS’ at TU Darmstadt, 2022, ‘Beyond Smart Cities’ at Malmö University, 2022, ‘Platform Governance’ at Duisburg-Essen University, 2022, the Platform Labour workshop at Amsterdam University, 2022, the ‘Digital Capitalism: Labour’ panel at AAG, 2023, the ‘Decentering Platform Urbanism and Work’ session at RGS 2023 and the INDL-6 community. We also thank Professor Karin Schwiter and Professor Lindsay Blair-Howe for their insightful comments on the earliest version of the project that encompasses this manuscript. We also thank Professor Niels van Doorn for commenting on a later version of our draft and providing insightful critiques. Furthermore, we thank Matias Palacios for editing the first draft of this article. Finally, we thank all the members of the Spatial Development and Urban Policy Group (SPUR) for their valuable input and support. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Abstract

Amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the food and grocery delivery sector became a multibillion-dollar industry, making riders with squared backpacks visible in our urban landscapes. We explore the role of quick delivery platforms in spatial production—and especially the strategies platforms employed and the tactics of platform workers in relation to this production. By adopting a Lefebvrian perspective, we introduce the concepts of ‘strategies of spatial abstraction’ and ‘spatial tactics of resistance’. We argue that strategies of platforms such as territorialization and digital Taylorism homogenize spatial relations, while platform workers use tactics to resist and to negotiate their everyday lives mediated by platforms. We draw on vignettes from Barcelona and Berlin to illustrate the spatial implications of these strategies and tactics. Territorialization anchors platforms to urban locations through physical infrastructure, while digital Taylorism utilizes algorithms to standardize spatial practices. These strategies contain contradictions: territorialization reduces worker atomization, while digital Taylorism catalyzes worker resistance tactics, especially logistical resistance around the platforms’ dark stores and warehouses. This article contributes to the growing body of literature on platform urbanism, revealing the complex and often contradictory nature of platform-mediated production of urban space.

Introduction

The consolidation of the platform economy has sparked intense scholarly and public debates, particularly about its impact on urban space, where the focus has been on the challenges emerging in housing (Ferreri and Sanyal, 2018; Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018), mobilities (Adebayo, 2019; Stehlin et al., 2020) and labour (Parwez and Ranjan, 2021; van Doorn and Vijay, 2021; Altenried, 2022). Transnational capital has found ways to embed platforms’ practices into the scale of everyday life (Leyshon, 2023), territorializing their presence in cities worldwide and coordinating large numbers of people and services in sociotechnical arrangements (Richardson 2020a; 2020b). The practices of these platforms seem to have a broader and deeper reach than ever before, playing a vital role in the production of urban space in contemporary societies.

In this article, we examine the strategies quick delivery platforms for food and groceries use, and the tactics platform quick delivery workers (riders) employ to reveal a dynamic process of contested spatial production. We focus on two quick delivery service platforms: Gorillas in Berlin and Glovo in Barcelona. Quick delivery platforms promise deliveries within ten to 30 minutes, pioneered in the European markets by Turkish company Getir in 2015. However, Barcelona-funded Glovo adapted its more traditional food delivery model to quick delivery by opening ‘dark stores’ (micro-fulfilment centres), called Superglovo, in late 2017. By further expanding its model in 2018, Glovo could offer deliveries in shorter times than its competitors and reached an investment of US $1.2 billion in its last investment round in 2021. During the Covid-19 pandemic, several other companies, such as Berlin-based Gorillas, saw business opportunities. Since May 2020, it has been focusing solely on quick delivery, using a marketing slogan that claims ‘from store to door in ten minutes’, and its funding reached US $1.3 billion when it was acquired by its competitor Getir in late 2022.

Without a doubt, the Covid-19 pandemic acted as catalyst for the delivery sector, which became one of the most attractive investment opportunities for venture capital during this period (Lewin, 2021). Estimating the impact and size of the platform economy is a difficult task. Nonetheless, recent efforts, such as the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) survey in 2022, estimate that, within the working-age population in the European Union (EU), ‘4.3% did platform work and 1.1% can be classified as “main platform workers”; that is, working 20 hours or more per week or earning more than 50% of their income through platforms’ (Piasna et al., 2022). Moreover, according to the European Council, the EU platform economy is the source of income for over 28 million people and its revenue has seen a fivefold growth in four years, from 3.4 billion euros in 2016 to 14 billion euros in 2020, with food delivery recording a growth rate of 125% during the Covid-19 pandemic (EU, 2022). These estimates clearly show that the platform economy has been thriving, becoming a relevant source of labour for people in recent years.

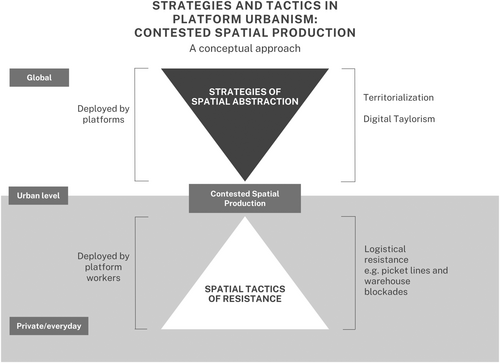

We study the impacts of platform urbanism using a conceptual framework that builds on Lefebvre's (1991) production of space. Specifically, we conceptualize and identify strategies of spatial abstraction of platform firms and spatial tactics of platform workers’ resistance, conceptually linking Lefebvre with de Certeau's ([1988] 2011) work by analysing two vignettes in Berlin and Barcelona. Our aim is to bring these conceptual ideas into the study of digital platforms and their spatial implications beyond these vignettes on place-based platform labour. This engagement allows us to understand how the strategies of quick delivery platforms and platform delivery workers’ tactics unfold, resulting in a process of contested spatial production. Such a conceptual approach gives us a framework to examine the actual mechanisms behind the production of space in the age of platforms, the role of the multiple actors and scales involved in this process, the different outcomes of these interactions and the contingent conditions that give way to workers’ resistance. Furthermore, we highlight the importance of the urban as a space of mediation, between the simultaneous functioning of Lefebvre's three levels of social reality (namely global/structural, urban and private/everyday) (Lefebvre, 1991: 155; 2003: 78; see also Schmid, 2022: 185–86). The global (platforms) and the everyday (platform labour) are both mediated at the level of the urban and its particular conditions (see Figure 1). These tensions and interactions thus unravel in cities, especially since platforms rely on their capacities to make space readable and exchangeable to maximize their profits.

In recent years, there have been several efforts to illuminate the linkages of platforms and the urban through a relational lens, allowing us to see them as ‘flexible spatial arrangements that are territorialized through a range of networked urban entities beyond that of the interface and the algorithm’ (Richardson, 2020a: 458). A relational lens means engaging with the conception of the platformized urban as that which is produced not by one but by multiple actors, where resistance as well as ‘acquiescence, subversion, and encroachment’ (Qadri and d'Ignazio, 2022) are key actions undertaken by platform workers in this ongoing and complex process. This approach allows us to understand that global (or structural) forces have an impact on everyday urban life. Yet, they are contested, creating at the level of the urban a space that has a tendency towards standardization and homogenization, but is at the same time fractured and full of potential for difference.

As the expressions of platform urbanism unfold in the tensions between global structures and everyday urban life, labour can offer critical insights into these interactions in urban contexts; therefore, in this article we focus on labour-based platforms, particularly work-on-demand platforms, defined by Tan et al. (2021: 2) as ‘platforms [that] match customers with workers to carry out traditional physical work, such as taxi driving or house-cleaning’. Within the work-on-demand sector, we engage with last-mile delivery platforms—particularly with quick delivery1—as they have achieved ubiquitous status and have boomed in contemporary urban landscapes, whether through their armies of riders or through the presence of their warehouses, ghost kitchens and dark stores (Shapiro, 2023).

Even though it is true that platform-based labour provides opportunities to many who are not able to access traditional labour markets (Altenried, 2020), the new categories of work, for example, crowd work or work on demand (Tan et al., 2021), make platform–worker relations challenging and ever-changing. Issues such as misclassification (Defossez, 2022; Piasna et al., 2022), exploitative algorithmic management (Altenried, 2020; Vecchio et al., 2022) and dynamics such as coercive or false flexibility (Richardson, 2020b; Shibata, 2020) deepen the exploitation of racialized and gendered labour in this sector (van Doorn, 2017; Altenried, 2021; Gebrial, 2022). Despite these challenges, the agency of platform workers adapts and changes, as structural conditions and individual experiences co-articulate and ‘establish what modes of agency are possible, ranging from (constrained) decision making, strategizing and individual and collective forms of organizing and resistance’ (van Doorn, 2023: 163).

These tensions are heightened under new platform business models such as quick delivery, which extract value not only from workers but also from cityscapes (Sadowski, 2020). Delivery platforms have traditionally relied on the coordinating capacity (Richardson, 2020b) of differently networked entities, such as riders, consumers and restaurants (Richardson, 2020a). Quick delivery platforms, specifically, anchor their presence in the urban landscape through warehouses, dark stores or ghost kitchens, while optimizing the spatial practices of their workers. Thereby, they aim for spatial and temporal optimization through owning more central locations throughout the city that allow for shorter delivery times. For example, Gorillas reported on its website that, by May 2022, it had 237 warehouses in 64 cities; 19 of these in Berlin.2 The figures for Glovo are harder to estimate, as the company does not provide open data about its delivery areas, but by November 2022, we identified six Superglovo dark stores in the area of central Barcelona; we visited all of these during our fieldwork. This spatial anchoring allowed both companies to optimize their delivery promise of shorter delivery times than that of their competitors.

In this article, we explore processes of spatial production in the age of platforms. We thereby probe how a conceptualization that links Lefebvre's and de Certeau's spatial analysis of global and everyday dynamics with platforms’ strategies and workers’ tactics of resistance can contribute to a contemporary understanding of this process in the urban. In the quick delivery sector, owing to the existence of dark stores, contradictions emerge when nodes of supply chains are fixed in a territory, as these nodes are visible and exposed to practices of resistance by workers who can also use spatial anchoring to their advantage. Here the traditional advantages of an atomized work force (Graham, 2020) and the flexibility of the nodes that characterize food delivery are diminished.

Inspired by Lefebvre's transductive approach—meaning that empirical research informs theory building and vice versa (for more on the transduction approach, see Schmid 2022: xvii, xxv, 44)—we apply these conceptual contributions to empirical situations. We present two vignettes that frame quick delivery as an extreme case in the platform economy, where spatial, temporal and resistance practices are at the centre of the struggles. We highlight the tensions between strategies of spatial abstraction and tactics of resistance in the cities of Berlin and Barcelona. Both cities have experienced labour struggles associated with quick delivery platforms and have high concentrations of migrant workers in this sector (Alyanak et al., 2021; Metawala, et al., 2021). We use these vignettes to flesh out these conceptual contributions in the light of recent events. Before we start with our conceptual and empirical endeavour, the following section sets the scene by presenting the ongoing discussions on the role of platforms in the production of the urban in the wider setting of platformization.

The production of space in the age of platforms

The role of platforms in contemporary society has been widely discussed in recent literature and has been addressed mostly through the lens of platform capitalism (Srnicek, 2017). However, to understand the urban role of platforms, it is necessary to go beyond the structural–economic relations of platformization. Here, Sarah Barns's (2014; 2018; 2020) conceptualization of platform urbanism is key, as it is defined as a ‘relational process’ (ibid., 2020: 21) in which platforms reconfigure urban relations between multiple actors, regardless of whether these are companies, the state, users or workers, redefining and mediating their spatial relationships in urban contexts.

The pervasiveness of platforms in cities is necessarily linked to their capacity to leverage capital from investors and to use data as capital for their growth spurts (Sadowski, 2019). Nonetheless, focusing solely on the unidirectional role of capital in the urban through platforms succumbs to the pitfalls of a monolithic vision of the production of space in which capital is the only driver of this process. Yet, in the platform literature, there are only a few discussions about space beyond its relationship solely to capital. Different authors deal with the structural conditions of platform urbanism in the production of digital and physical space (Sadowski, 2020), platforms and their linkages to the built environment as fragile spatial fixes (Stehlin 2018; Stehlin et al., 2020) or the production of digital and radical spaces through platform delivery labour (Briziarelli and Armano, 2020). Despite this focus on structural conditions, conceptualizations such as the ‘glitch’ (Leszczynski, 2020) offer rich understandings on the intertwining of the digital and cities, honouring the specificities of urban contexts, unexpected happenings, hacking opportunities and the potential for difference, while fending off monolithic narratives on urban capital, and giving space and agency to the narratives of other actors.

Based on our reading of the literature, we believe that conceptualizations bridging structural narratives with everyday practices, which see the urban as a process in constant production (that is, as more than a stage), is a necessary task in the field of platform urbanism, to which we aim to contribute. The question is not just what type of space is produced in platformized urban contexts, but also how these spaces are produced and which actors and mechanisms are behind these processes. We chose to engage with quick delivery platforms through a Lefebvrian lens because of the extreme reliance of this business model on spatial and temporal relations and because of the visible linkages between global capital, the platforms’ strategies, workers’ tactics and the particular conditions of each urban context in which these struggles unravel. In the section that follows, we bring Lefebvre's work on the production of space and de Certeau's focus on everyday life to platform urbanism to try to identify the mechanisms through which platforms push towards the homogenization of space for profit capture and the countervailing forces emerging from workers’ resistance.

A Lefebvrian perspective on platforms and the urban

If every society produces a space—its own space (Lefebvre, 1991)—it is worth asking which space is produced in urban societies mediated by platforms. Considering the key role that capital plays in leveraging the platformization of the urban and the diverse and rich expressions of struggle and resistance in cities worldwide, we think it is necessary to explore the mechanisms of spatial production in this scenario. Therefore, we have adopted the threefold dialectical approach (Lefebvre, 1991) to contextualize spatial production in the age of platforms, how abstract space plays a key role in this process, and how Lefebvre's concepts unfold in platform urbanism.

First, it is crucial to address the concept of abstract space. According to Lefebvre, abstract space is associated with commodities and exchange (see Lefebvre, 1991: 49; Schmid, 2022: 342–45). It is a ‘formal and quantitative’ space that is conducive to optimization and logistics (Lefebvre, 1991: 49). Abstract space fosters the reduction or abstraction of spaces to geometric and visual logics, both of which are functional to the rationalization of space (Lefebvre, 1991: 285–86). Therefore, it plays a crucial role in understanding the ongoing platformization of urban spaces, as it represents a ‘space of accumulation, calculation, planning, programming’, and it is dominated by a tendency towards homogenization (Schmid, 2022: 345). We argue that even today, this space remains dominant, and its characteristics are evident in the logics and strategies that platforms employ to capture more value from urban environments.

Lefebvre uses the threefold spatial dialectic, commonly known as a spatial triad, to understand the process of spatial production. This triad is composed of conceived, perceived and lived spaces (for further details, see Lefebvre, 1991: 33 and Schmid, 2022, Chapter 6). We are interested in understanding how this approach allows us to make sense of the relationship between the production of space and the platformization of the urban. By examining the inseparable nature of these three dimensions, we can shed light on the link between platformization of the urban and labour.

The dialectical relationship between these logics pushes for a conception of space that can simplify and abstract sociospatial relations rooted in the practices of the industrial society and strategies of value capture such as Fordism and Taylorism (Schmid, 2022: 347). We can also find these strategies in platform urbanism being amplified through surveillance technologies and algorithmic management in the form of digital Taylorism (Altenried, 2020; 2022; Schmid, 2022) and simplifying and reducing spatial practices to functional utility (see Lefebvre, 1991: 313; Schmid, 2022: 350).

Lefebvre concludes that abstract space contains violence (see Schmid, 2022: 355) in the guise of knowledge and efficiency. This discourse is dominant in narratives about automation of labour and the platform economy (Lin, 2021; Altenried, 2022), where ‘logic and logistics conceal this latent violence, which does not even have to show itself to become effective’ (Lefebvre 1991: 358; see also Schmid, 2022: 355). This violence underpins platforms and is usually hidden under optimization criteria and technological savviness; hence, unravelling these mechanism and strategies is crucial for our understanding of the role of platforms such as quick delivery in the production of the space of cities, which are progressively more and more mediated by them.

In recent years, researchers have identified certain mechanisms behind how platforms relate to the urban and to labour; nonetheless, there is no coherent narrative bringing these mechanisms together as part of the production of space. Lizzie Richardson has focused on platforms as an expression of different networked actors and entities in urban environments, leading her to understand platforms as flexible spatial arrangements (Richardson 2020a; 2020b). Others, such as Briziarelli and Armano (2020), have addressed the tensions between the production of what they call abstract digital space and the pushback from embodied labour of gig workers. In our understanding, Briziarelli and Armano, like Richardson, consider the role of the spatial dimensions of these networks as part of a process of territorialization. For Richardson, territorialization is expressed through these different networked entities. However, for Briziarelli and Armano, the (re)territorialization of the platform and its efforts at spatial abstraction are canalized through the human agency of gig workers, making it present in urban landscapes through labour, but also through resistance (ibid.: 8).

Furthermore, these authors highlight the role of algorithmic processes behind platform labour. For Richardson, the software aspects of platforms cannot be separated from the territorialization of the linkages between the entities of these networks. In the work of Briziarelli and Armano, algorithms play a central role in the production of abstract space by coordinating the ‘living human capabilities with the procedures codified by the algorithm’ (ibid.: 8). Both approaches attest to what Moritz Altenried (2022) defines as digital Taylorism: the optimization of labour through software and hardware advancements.

We take these concepts and integrate them into the thinking of spatial production (Lefebvre, 1991), framing both strategies—territorialization and digital Taylorism—as coherent approaches used by quick delivery platforms to optimize spatial relations, and to make space and labour homogeneous, readable and therefore abstract. Our goal is to develop a conceptual understanding of the mechanisms of spatial production in the age of platforms, which we investigate alongside tactics of resistance by platform workers in the case of quick delivery services.

Strategies of spatial abstraction and spatial tactics of resistance

To understand the role of territorialization and digital Taylorism in the production of space, we conceptualize the process under which platforms rationalize urban space and embed themselves in the urban fabric as strategies of spatial abstraction. The existence of these strategies does not mean the absolute conquering of everyday life by platforms, but pinpointing these specific configurations allows us to shed light on the expressions of actually existing platformization (van Doorn et al., 2021) and the possibilities that exist to create space otherwise. In the section that follows we develop the concepts of strategies of spatial abstraction and spatial tactics of resistance by relying on the work of Lefebvre (1991) and de Certeau ([1988] 2011). The simultaneous consideration of strategies and tactics is designed to link the structural conditions under which platforms operate and become integral to urban systems, while highlighting the agency of people working through platforms, allowing researchers to move from metanarratives on structures to everyday life practices.

As mentioned earlier in this article, abstract space tends towards homogenization of the territory. For Lefebvre, this space is linked to certain logics or, better yet, certain strategies. The language of the strategy3 is present throughout the production of space and linked to ‘visual logics’ (Lefebvre, 1991: 128) designed to rationalize space and spatial relations through geometrical knowledge, thus creating ‘worldwide strategies now seeking to generate a global space’ (ibid.: 105). Lefebvrian abstract space relies on a wide repertoire of strategies that strive for reduction ‘through (functional) localization and through the imposition of hierarchy and segregation’ (ibid.: 318), both of which are aspects that remain present in the production of space in the platformized urban.

In this context, we think it necessary to describe these in platform urbanism as expressions of this global tendency towards abstraction, which unravels in the urban and clashes with the personal to reveal the fractures in this apparent homogeneity. Therefore, the work of de Certeau ([1988] 2011) not only offers a productive and conceptually coherent way to engage with the ideas of spatial abstraction and strategies, but also provides a conduit for understanding the fractured nature of abstract space through tactics.

Strategies of spatial abstraction: territorialization and digital Taylorism

We interpret this strategy as the logic of homogenization behind Lefebvre's spatial abstraction. By conceptualizing this parallel, it is possible to say that the strategy is intended to delimit a homogeneous territory, through visual logics of speed, readability and simplicity, while legitimizing its presence through the guise of knowledge. In the case of platforms, particularly quick delivery platforms, these three elements are present, allowing us to identify concrete strategies of spatial abstraction in this sector.The calculation (or manipulation) of power relationships that becomes possible as soon as a subject with will and power can be isolated. It postulates a place that can be delimited as its own and serve as the base from which relations with an exteriority composed of targets or threats, can be managed (de Certeau, [1988] 2011: 36, emphasis in original).

As stated earlier, we are concerned with the actual expression of spatial abstraction as part of the production of space. Therefore, we are looking at concrete pathways through which the concepts of strategies of spatial abstraction unravel in the urban, particularly in platform urbanism and labour. We now briefly conceptualize two strategies of spatial abstraction in quick delivery: platform territorialization and digital Taylorism. Why these two strategies and no others? Because we argue that these two strategies link the functions and effects of the platform not only with the urban, but also with workers’ labour to act as catalysts of contested spatial production.

For quick delivery, the physical anchoring of warehouses is key to achieving marketing promises of speedy deliveries, giving such platforms a locational advantage. This is what we call territorialization. The language of territorialization—and its variations4—in the contemporary Western tradition stems from Deleuze and Guattari (1983), who defined it as ‘the investment of energy in specific areas of the body and the economy, the withdrawal of such investments, and their re-investments elsewhere’ (see Holland, 2018: 7). Similar to the bodily metaphor, capital territorializes its presence in cities through platforms in multiple forms (Briziarelli and Armano, 2020; Richardson, 2020a; Shapiro, 2023), creating ‘landscapes of locational advantage that bridge the physical and the digital’ (Stehlin, 2018: npn), enabling platforms to capture value from the urban.

Research on work-on-demand platforms distinguishes between delocalized and localized on-demand work. The former provide ‘services that are offered regardless of worker-requester location’ and the latter ‘[facilitate] services between members physically situated within a shared geographical area’ (Tan et al., 2021: 2). Nonetheless, this definition is focused on the location of the worker and not the location of the assets controlled by the platform, as traditionally, these companies do not necessarily rely on assets, but focus on market coordination (Richardson, 2020a). Nowadays, in the delivery sector, it is possible to see a hybridization of the model, which relies on the territorialization of assets in the form of dark stores (Shapiro, 2023). These dark stores are defined as ‘micro-fulfillment centers for online purchases, typically converted retail properties … spaces optimized for picking, preparing, and fulfilling delivery orders’ (ibid.: 2). These micro-fulfilment centres, especially at strategic central locations, allow companies to reduce delivery times, which is the foundation of their business promise.

From our perspective, the rapid scaling of territorialization was fundamental in the rise of quick delivery services. In the example of Gorillas, the company highlights in its blog that since May 2020 ‘the startup has grown rapidly, expanding to more than 60 cities … and establishing more than 230 micro-fulfillment centers in nine countries … faster than any other German company before’ (Gorillas.io, 2022). The case of Gorillas is an exception, compared to the slower growth and consolidation of other quick delivery companies such as Glovo. Nonetheless, this extreme case clearly shows the extent of such a strategy of spatial abstraction.

Altenried describes diverse scales through which digital Taylorism operates (from streets to private homes). Nonetheless, we add to it the fact that space is more than the scenario in which platforms deploy their strategies; space is also an active component in the process, which is itself adjusted and optimized. As a strategy of spatial abstraction, digital Taylorism seeks to optimize, quantify and manage the processes that allow for the extraction of value not only from labour, but also from the urban (Stehlin, 2018). Technologies such as geolocation play a key role in spatial abstraction, making space functional for logistics operations, and readable for platforms and customers, both of which both make riders and their spatial practices a subject of constant surveillance (Vecchio et al., 2022) and optimization.How a variety of forms and combinations of soft- and hardware as a whole allow for new modes of standardization, decomposition, quantification, and surveillance of labour—often through forms of (semi)-automated management, cooperation, and control … These forms of algorithmic management and control of the labour process allow for new forms of coordination and control that can reach out onto streets or into private homes (Altenried, 2022: 7, emphasis added).

The abstraction of space requires the optimization of labour and vice versa: two facets of delivery stacking on each other, the tweaking ranging from how riders select their shifts to rearrangement of delivery areas. Usually the challenges emerging from these changes fall on the riders, who must deal with the new requirements and goals set up by the platforms in their race to compress space and time to maximize profit.

Nevertheless, despite all efforts to rationalize space and erase the bodily limits of riders, we know that there is no such thing as total homogeneity. Abstract space carries within itself the contradiction of being homogeneous–fractured (Schmid, 2022). Like the tendency of capital to abstract spatial relations, seeking homogenization through technological means coexists with the fractured reality disputed by multiple actors, markets and social and power relations that gives shape to the urban. What seems homogeneous is full of fractures and even glitches (Leszczynski, 2020), full of spaces with the potential for difference and interstices for people reclaiming space through different tactics. Therefore, in the next section we delve into the countervailing forces in the process of spatial production by engaging with the question of how spatial tactics of resistance take place in the quick delivery sector.

Spatial tactics of resistance: contingent conditions and the potential of difference

In the vignettes that inform this article, we deal with two instances of resistance that took place in the cities of Berlin and Barcelona, led by Gorillas and Glovo workers, respectively. To make sense of these events, we focus here on the agency of riders at the face of these strategies of spatial abstraction. We understand tactics as reactions to totalizing forces—as part of the ‘contradictory social process that is set in motion by differences’ (Schmid, 2022: 366–67). The space of the tactics is that of the difference, as an internal contradiction emerging from abstract space due to the homogeneous–fractured nature of it (Schmid, 2022). Through our understanding of abstract space in platform labour and urbanism, the concept of spatial tactics of resistance emerges.

If strategies are linked to the homogenization of space and abstract space, tactics indicate difference related to the interstices and spaces where the potential for difference is present. According to Schmid (ibid.: 367), difference for Lefebvre exists not merely as a ‘concept, as an imaginary form, but first and foremost as a practice that is experienced’. We therefore take this call to look into concepts focused on praxis by engaging with de Certeau's definition of a ‘tactic’ as a calculated action that arises from the lack of a proper location, requiring it to adapt and interact with an environment controlled by external forces. This tactic operates within the constraints set by those in power (the platform) exploiting the gaps and vulnerabilities in their domain (de Certeau, [1988] 2011: 37). Viewed through a Lefebvrian perspective, tactics are seen as spatial practices with the potential to generate alternative spaces. Consequently, tactics of resistance represent just one variation within a broader array of spatial practices that continually shape and reshape space, such as those addressed by Scott (1985) as weapons of the weak.

In the contemporary urban, owing to the predominance of the logics of abstract space, spatial practices are subjugated to productive moments, creating spaces and practices that are the ‘result of (repetitive) gestures of (serial) actions of productive labor’ (Schmid, 2022: 275). Therefore, labour acts as a twofold spatial practice, which on one side reproduces the conditions dictated by the strategies of the platforms, while also, when certain contingent conditions are met, opening up the pathway for tactics of resistance in the territory of the platform. We were able to detect this in practice in instances where workers turned the dark store and warehouse into a space with a potential for which it was not conceived, be this socialization, solidarity or logistical resistance.

Platforms as hubs between the global and the private rely heavily on labour as the fundamental spatial practice to provide their services. Whether labour is on-demand, crowd-work-based or linked to assets such as Airbnb or ride hailing (Tan et al., 2021), it is rationalized under the guise of speed, legibility and simplicity. Hence, in platform urbanism, labour is much more than labour; it is a necessary condition for platforms to come into being, while it also carries the contradictions and the potential resistance to platform strategies. As we show in the vignettes, logistical resistance (Danyluk, 2022) is one expression of spatial tactics of resistance, which starts through spontaneous efforts within someone else's territory, requires contingent conditions that enable or limit their success and calls for the attention of those originally controlling space without necessarily congealing into a strategy or an institution.

Vignettes on quick delivery in Berlin and Barcelona

Based on our understanding of the relevance of praxis in Lefebvre's work (see Schmid, 2022: 79–83), we now address the actual expressions of strategies of spatial abstraction and spatial tactics of resistance in quick delivery platform urbanism. We examine specific spatial and temporal configurations in which platform strategies and worker spatial tactics clash at the urban level in Berlin and Barcelona, connecting conceptual developments with the actual conditions of contested spatial production that have unfolded in both cities.

Quick delivery platforms, promising deliveries within ten to 30 minutes in high-density urban areas, rely on territorialization and digital Taylorism, thereby pushing riders towards risky situations (for example, high speeds associated with the quick delivery times required from them) (see Zheng et al., 2019; Figueroa et al., 2021). These situations catalyze spatial practices such as resistance and expose contradictions within the platforms’ strategies of spatial abstraction. We believe that cities in the global North are also ‘socio-spatially structured to profoundly burden and distress the poor in a continuously affirmed and reproduced reality’ (Wilson and Jonas, 2021: 1337). Therefore, it is highly relevant to analyse the linkages between platformization of the urban and labour in the interstices of the global North, where migrant labour from peripheries still bears the brunt of these burdens.

Our vignettes are informed by 22 documents5 from Berlin (17 July 2021–30 November 2021, see Appendix 1) and 276 from Barcelona (11 August 2021–12 September 2021, see Appendix 2). For Berlin, we analysed online news, documentaries and commentary pieces in German and English, ranging from Deutsche Welle to Wired Magazine. For Barcelona, we examined online news, legal documents, journalistic accounts and labour union websites in Spanish, Catalan and English, from El Economista to the online edition of Público. Details of these articles appear in Appendices 1 and 2. They range from well-established media outlets and legal repositories to smaller grassroots media outlets such as labournet.tv.

Given our reliance on online news, we are aware that engaging with these types of documents produces several challenges, such as limited access to certain sources owing to lack of capacity of search engines to index the ever-growing surface of the internet, the possibility of smaller websites being discontinued, or the personalization of results towards a particular user through a ‘filter bubble’ (Blatchford, 2020: 147). Nonetheless, it is also necessary to highlight the advantage of these approaches, such as enabling the researcher to ‘cast a “wider net”’ to obtain more diverse sources (Newman et al., 2021: 1382), or the capacity of online content for ‘revealing insights into topics which are not swayed by the researcher's own agenda’ (Wilkinson and von Benzon, 2021: 333). In this context, we acknowledge that the principles of ‘accountability, transparency and care’ (May and Perry, 2022: 124) are still fundamental when engaging with digital sources. Therefore, we took the necessary steps of manually reviewing, reading and analysing the cited sources, as well as engaging with a wide range of sources to try and overcome some of these challenges to a certain degree. Hence, our media analysis mainly focuses on reconstructing timelines and corroborating places, dates and events. This analysis was complemented by two-week visits to both cities in November 2022 to verify the locations of dark stores and strike areas.

The vignettes are neither representative nor totalizing, but illustrative of unique spatio-temporalities in which cities and platforms interact (Leszczynski, 2020). These vignettes connect global aspects of capital funding for quick delivery platforms, strategies of territorialization and digital Taylorism and accounts of platform workers’ resistance through spatial tactics.

Territorializing and wildcat strikes: Gorillas in Berlin

At the height of the pandemic in May 2020, quick delivery company Gorillas was founded in Berlin, with the objective of ‘creating a world with immediate access to your needs’ (Sümer, 2022). This statement indeed holds power, because immediate access to your needs implies someone or something attending to those needs whenever and wherever you are. It demands omnipresence. Under this promise, and taking advantage of the situation created by the Covid-19 lockdowns, Gorillas quickly managed to leverage investments from venture capital, achieving a US $1 billion valuation within less than a year (Partington and Lewin, 2021) and achieving 233 dark stores in 71 cities at its peak. Berlin has been one of its largest markets, with 18 dark stores in the first trimester of 2022.7

The premise of Gorillas was simple: to deliver groceries to your door within ten minutes. It is therefore an excellent example of the territorialization of the platform. Despite being sold in December 2022 to the platform Getir, by the end of 2022 it still held 18 dark stores throughout different districts in the city. While Gorillas retreated from several markets in 2022 and faced operational and labour-rights-related issues, Berlin remained Gorillas’ territorial stronghold, keeping its dark store presence and numbers steady until the end of 2022.

On 1 October 2021, riders from Gorillas voted to strike, paralyzing the work of the platform in its Bergmannkiez warehouse. The demands were related to occupational injuries from carrying excessive weight, obscure firing procedures, issues with warehouse management and the implementation of internal company projects. One of them was Project ACE, which, as several riders told the German daily newspaper Tagesspiegel, were designed to ‘streamline shift schedules … [which meant that] delivery frequencies for individual riders were significantly increased’ (Kluge, 2021a) and riders were ‘ending up with scattered schedules’.8

It did not take long for the Schöneberg and Mitte warehouses to join the wildcat strike, while the Gesundbrunnen warehouse joined the day after (on 2 October). These strikes are known as wildcat strikes, as they are autonomous and not organized by a recognized trade union, meaning, in this specific case, the spontaneous halt of the operations of the quick delivery services in four out of 18 locations in Berlin. The tactics of the riders, beyond using their position as the articulators of the supply chain, included turning their bikes upside down while maintaining a picket line, and preventing any strike-breakers from using them. The picket lines and blockades of the warehouses (see Figure 2) seemed to disrupt the functioning of the last-miles supply chain in the affected neighbourhoods effectively; this was verified by journalists of the online publication Motherboard (Geiger, 2021).

The riders’ demands addressed issues such as ‘no more computer-generated chaos; we need schedules made for people with real lives’ (Kluge, 2021b), addressing the fact that riders have to deal with idle time, while always having to be ready for the algorithmically optimized schedules that respond to user demand and not to actual rider availability. Aside from the algorithmic chaos, riders stressed the need to improve occupational safety, highlighting issues such as ‘the electric bikes are not suitable for the load’ (Kluge, 2021b) and lack of suitable equipment. Furthermore, life-threatening situations such as traffic accidents are ever-present in a business whose need for speed is central to fulfilling the ten-minute promise.

By the evening of 4 October, after four days of logistic resistance, Gorillas hired a private security firm to prevent the workers from entering the warehouse. At the same time, Gorillas’ management decided to terminate all the workers who took part in the strikes—affecting around 350 riders and warehouse staff. This action was taken based on the argument that these strikes were legally inadmissible under German labour law and represented a scenario in which resistance had a complex outcome for platform workers, particularly those whose residence status was dependent on a work contract.

Digital Taylorism and territorial struggles: Glovo in Barcelona

On 12 August 2021, after months of discussion and deliberation, the ‘Ley Rider’, or Rider Law, came into force in Spain as a part of a ‘tripartite collective bargaining agreement’ (Eurofound, 2021), which included workers’ unions, industry representatives and the Spanish government. The aim of this law was to recognize ‘food delivery riders working for digital platforms as employees rather than independent contractors’ (Eurofound, 2021). To ensure this, it contains two provisions: one is based on the presumption of a contractual relationship, and the other is focused on algorithmic transparency. For the purpose of this vignette, we focus on the first, which applies to ‘the activities of distribution of any type of product or merchandise, when the employees exercises [the] faculty of organization, direction and control, directly, indirectly, or implicitly, through the algorithmic management of the service or working conditions, via a digital platform’ (Eurofound, 2021).

In response, delivery platforms such as Glovo tried to tailor their position to the Spanish law by finding legislative loopholes. Glovo, for example, aimed to hire only 20% of its workforce as employees (Alonso, 2021b), while retaining the rest as freelancers.

Nonetheless, this tinkering was not limited to legislative experimentation from the side of the platforms, but also included a realm where they have much discretion: the algorithm. Once the law was implemented, Glovo Spain introduced an option in its app for riders to ‘multiply’ their earnings within a range from 0.7 to 1.3, meaning that riders could underbid and sell their labour at a lower rate than the regular rate of 1 to 1. The idea behind the algorithmic tweak was to enable riders to set the price of their work on their own, separating the responsibility of Glovo towards the worker even further, in response to the first provision of the Rider Law. According to different sources, this experimentation with the multiplier meant a transfer of requests to riders with lower multipliers. This situation left riders bidding above 1.0 out of the loop. Glovo denied these reports, attributing the lower demand to the summer season.

This experimentation with the algorithm created profound discontent in the rider community in Barcelona, and it was met with a fast response from autonomous workers and unions alike. Between 13 and 16 August, 50 to 100 demonstrators gathered in front of Glovo's headquarters in Barcelona, led by independent rider organizations, with participants from Central General de Trabajadores (CGT) and Comisiones Obreras (CCOO). By 17 August, employees from the six Glovo supermarkets in Barcelona joined the riders on their fifth day of protest, which transferred the pressure of protesting to public spaces such as Plaça Catalunya, the Arc de Triomf (see Figure 3) or outside Glovo Headquarters and Superglovo dark stores.

According to one CCOO representative, Carmen Juarez (Wray and Juares, 2021), the demands of workers at the quick delivery locations of the company Glovo supermarket had been ignored for months. The events following the implementation of the law acted as a catalyst, which mobilized workers to take a stronger stance on the matter. This moved the industrial action to the dark stores, which highlighted their key role in Glovo's supply chain, as it ensured the vertical integration of Glovo's business model. Consequently, the privileged position of the dark stores allowed Glovo supermarket workers to paralyze the operations of Glovo in its dark stores.

On 18 August, a representative from CGT Riders told El Salto (see Forner, 2021) that Glovo gave in to the demands of the riders, reducing the range of the multiplier by restricting options to between 1.0 and 1.3 to eliminate the possibility of underbidding. Despite this, owing to the complex and diverse composition of the Glovo riders, logistical resistance continued and was catalyzed by algorithmic experimentation.

As the paralysis of services continued, on 23 August the largest trade union in Spain, CCOO, called for nine days of strikes in Glovo supermarkets, starting on 27 August, to demand improved labour conditions for workers. Glovo's workers described the dark stores as spaces that had all the necessary elements for an efficient logistical deployment but lacked consideration for basic human needs, such as allowing riders to use the bathrooms in the facility (Escofet, 2021). The demands of this second stage of the August demonstrations in Barcelona moved beyond the issues raised by the reactive algorithmic experimentation. The new demands were made in response to the conditions of the territorialized platform, the built environment and the facilities of the warehouses, with workers demanding ‘space to wait for orders during the working day, with access to toilets, water and a locker with a password to leave their belongings’ (ibid.).

The strike, planned for nine days, came to a halt on 2 September so that workers could engage in negotiations with Glovo. According to CCOO declarations, this strike was ‘an unprecedented success’, as it was the first legally called strike to take place in a digital platform delivery company in Europe. This was followed by a definitive cancellation of the strikes on 9 September, after Glovo agreed to the possibility of indefinite contracts for warehouse workers in response to the effective picket lines at its warehouses.

Discussion: contested spatial production in platform urbanism

The analysis of these vignettes, which reconstruct events in Berlin and Barcelona, make it possible for us to discuss and refine our understanding of how quick delivery relates to the production of space and enables us to unravel strategies of spatial abstraction and the spatial tactics of resistance deployed by workers.

Territorialization and digital Taylorism: creating contingent conditions

The events in Berlin and Barcelona show that strategies of territorialization and digital Taylorism overlap. Despite slight differences in the business models of Gorillas (solely focusing on quick delivery) and Glovo (applying a mixed model), it was clear that the struggles of the platforms’ riders were similar. These struggles were catalyzed by the interaction between strategies of territorialization and digital Taylorism. Our aim here was to conceptualize these strategies as the mechanisms through which quick delivery platforms attempted to homogenize space and spatial relations to add a spatial understanding to platforms studies. Yet, these strategies clashed with urban realities, labouring bodies and local regulations. This is where interaction between the two strategies catalyzed the riders’ tactics of resistance, which in both cases centred on logistical resistance and its effectiveness.

The strategies of spatial abstraction enact the simultaneous dominance of the geometric and the visual logics that subjugate the spatial practices, making them functional to the logics of technical knowledge and efficiency preached by tech companies. In the case of quick delivery platforms, spatial relations are initially restricted to those of logistic labour, reducing workers to ‘machinic functions’ in the ‘eyes’ of the platform (Benvegnù et al., 2021). Hence, platforms rely heavily on their capacity to reduce spatial relations, such as labour, into the logic of simplicity that is predominant in abstract space, to ‘continually reform the city by generating spatial representations, which influence perceptions, which in turn impact countless flows and interactions of people and places’ (Graham, 2020: 454). Nevertheless, this continuous reformation, despite the platforms’ wildest dreams of abstraction, is necessarily relational and dependent on the engagement of users and workers in the platform ecosystem (Barns, 2020). Put simply, without workers there is no platform.

However, the relationality of spatial practices goes beyond labour and is defined as how ‘[people] through their movements, activities, and actions … generate a complex social space which is constantly changing’ (Schmid, 2022: 276). During the events in Berlin and Barcelona, the spatial practices of platform workers, initially restricted to the realm of their logistical endeavours, shifted towards spatial tactics of resistance. Riders were not engaging in industrial action against work, but against the challenging scenarios orchestrated by Gorillas and Glovo, which not only made their work harder but also had consequences for their health and safety, as seen in other cases (Papakostopoulos and Nathanael, 2021). These hazards, which stemmed from computer-generated chaos, unrealistic driving times (Chen and Sun, 2020), lack of proper equipment and algorithmic experimentation, are not inherent to labour, but are inherent to the strategies of value capture of the platforms and represent an attempt to discover the lowest thresholds at which workers can still be productive without paralyzing the platform's pursuit of profit.

This focus on lowest thresholds becomes evident when platforms territorialize, as workers realize the value of face-to-face encounters and of recognizing each other as peers (Morales-Muñoz and Roca, 2022), which reduces the almost inherent atomization for which platform labour is known (Graham, 2020).

This territorialization is particularly relevant when the territorialization strategy requires not only the opening of dark stores, but also the ‘steady supply of replaceable migrant labor’ (van Doorn, 2023: 172)—riders, warehouse managers and pickers who are hired and fired depending on the requirements of the platform, which acts as a factor that catalyzes resistance.

When these platforms territorialized, named by some investors as ‘logistic capillarity’ (Stoneweg, 2021), there was a shift from platforms acting as mere coordinators of offer and demand towards their deeper intertwinement with classic models of logistics business, which conflicted with one of the key advantages that it had over its workers: atomization. Considering that platforms have constantly engaged in practices of driving down wages and worsening labour conditions (Woodcock and Graham, 2019), the combination of territorialization and digital Taylorism in both cases created the contingent conditions (Danyluk, 2023) that enabled logistical resistance with varying short-term results. For example, in Berlin, one short-term effect was the massive firing of Gorillas employees, while in Barcelona, it achieved the elimination of the under 1.0 multiplier and secured a contractual relationship for those working at Superglovo.

Reclaiming the fragmented city through logistical resistance

The overlap of territorialization of the platform and digital Taylorism reveals the fuzzy territoriality of the platform, which originally answered to a network of riders and restaurants and later acquired a territorial presence to create a space of contested spatial production (see Figure 1). The emerging contestation is underpinned by a praxis that points towards the recovery of centrality as a ‘locus of action’ (Lefebvre, 1991: 399), not only of the warehouse as a space of labour, but also of the city as the space for living. This struggle for recovering centrality means being able to work without risking one's health, without having to experience the urban routine only through the lens of the algorithm. It means regaining dignity but also enjoying work as a freelancer, under a contract, as a migrant or local worker.

The production of space in platform urbanism is a result of these instances of contestation. Resistance in these cases emerges in the contradictions of the strategies. The conditions and grievances that emerge from the business model of quick delivery re-signify the space of labour with political meaning (for example, the warehouse is not only the space of the logistics, but also the space of organization and protests). Territorialization makes possible an oppositional understanding of the ordering of the platform—a willingness to defy digital Taylorism—even when the agency (van Doorn, 2023) and temporalities for migrant platform workers might be severely restrained and risks might increase owing to workers’ legal/migratory status.

Therefore, what we have tried to conceptualize in this article is how quick delivery platforms and their efforts of homogenization through these strategies constantly coexist with the fractured nature of abstract space to highlight the crucial position of platform workers to work with these fractures. These fragmentations have been addressed by other scholars in the form of the ‘glitch’ (Leszczynski, 2020), multiple forms of resistance and organization (Briziarelli and Armano, 2020; Chen and Sun, 2020; Riordan et al., 2022; Danyluk, 2023; Riesgo Gómez, 2023) and practices of repair (Qadri and d'Ignazio, 2022) or even compliance (van Doorn, 2023). We believe that our contribution follows this line of thought, offering a conceptualization based on urban theories that keep an eye on structural conditions, while bridging these conditions by considering the role of everyday spatial practices in the production of space. We do this through a spatial and urban framework that enables us to identify strategies of spatial abstraction, based on the work of Lefebvre. We believe that this conceptualization has relevance beyond the quick delivery sector and can address the wider realm of platform urbanism, where global conditions of platformization clash at the level of the urban with everyday spatial practices, such as resistance, which we understand through the work of de Certeau.

We believe that the potential for a Lefebvrian differential space is key—the space emerging from tensions and contradictions, as it ‘recognizes the centrality of embodied experience to the production, reproduction and contestation of urban space’ (Latham et al., quoted in Briziarelli and Armano, 2020: 5). However, this potential for differential space is rapidly co-opted into actually existing expressions of platformization in the urban. By using flexible spatial arrangements (Richardson, 2020a) with the capacity to ‘retreat to their ephemeral digital dualism’ to abdicate responsibility (Graham, 2020: 454), most platforms are in a position to incorporate the push that comes from the spatial tactics of resistance. Even giving in to the demands of workers does not completely disrupt their models, as was evident in the cases of Gorillas in Berlin and Glovo in Barcelona: both companies continued to operate despite heavy contestation from their workers.

Conclusion: finding fractures within homogeneity

Our aim with this article was to understand the mechanisms by which quick delivery platforms play a role in the production of space. We saw that the strategies platform firms applied in quick delivery were focused in particular on the optimization of space and labour as a spatial practice in the form of territorialization and digital Taylorism. However, the contradictions that emerge from territorialization and digital Taylorism create contingent conditions for spatial tactics of resistance. In the two cases discussed in this article—Gorillas (Berlin) and Glovo (Barcelona)—the spatial tactics of resistance took the shape of logistical resistance, a concept that has traditionally focused on conventional logistics and not last-mile platforms. It is worth stating that the particular focus on resistance in this article does not mean that there are no other expressions of workers’ agency (such as solidarity networks, care practices, hacking and exploitation of glitches), nor does it negate other strategies deployed by platforms to commodify spatial and social relations, from the atomization of the workforce (see Graham, 2020) to efforts of regulatory entrepreneurship (see Barry and Pollman, 2016; van Doorn, 2021).

The use of a Lefebvrian lens allows us to simultaneously reveal the strategies of quick delivery platforms and the spatial tactics of resistance by platform workers. It provides a spatial reading of the wider role of labour-based platforms in cities and opens the door to dialogue between global/structural conditions of platformization and the everyday dimensions of this phenomenon, by connecting the thread with de Certeau's work. We believe that this analytical lens can contribute towards an understanding of the mechanisms underpinning the role of platforms in the production of space.

In our investigation, we focused on quick delivery platforms because, despite being short-lived ventures, they represent one of the most extreme examples of platform labour, which push the limits of space and time and of workers’ wellbeing, as highlighted by workers during the demonstrations described in the vignettes. Furthermore, their reliance on speed/time (or the visual) raises new questions about the temporalities emerging from the contested process of spatial production in platform urbanism.

Without a doubt, the list of ways in which space is produced in platform urbanism is as long as the list of platforms that exist. The reach of platformization goes from the intimacy of dating to global logistics. All these platformized spaces are subject to different forces, minor or major struggles, and individuals’ efforts of resistance, compliance and even enjoyment. Nonetheless, the aim of these strategies is to make space and spatial relations homogeneous and functional to their ends. Therefore, an understanding of these mechanisms, and how our interactions as platform users or platform workers can both reproduce and resist these forces, allows us to (re)think the possibility of difference, where we might find the fractures within what seems homogeneous, and possibly offer alternatives to the current profit-techno-solutionist perspectives dominating this sector.

APPENDIX: ―Sources: vignette Berlin

| Event | Date | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Gorillas founded in Berlin | May 2020 | Sümer (2022b) |

| Gorillas reaches US $1 billion valuation | Partington and Lewin (2021) | |

| Gorillas has 233 dark stores in 71 cities, with 18 in Berlin |

January–March 2022 |

Gorillas.io (2022) |

| Gorillas sold to Getir | December 2022 | Dillet (2022) |

| Gorillas retreats from several markets | 24 May 2022 | Sümer (2022a) |

| Operational and labour-rights issues | Flakin (2021) Kluge (2021c) Krantz (2021) | |

| Riders in Berlin vote on striking, paralyzing Bergmannkiez warehouse | 1 October 2021 |

Geiger (2021) labournet.tv (2021) |

| Demands related to occupational injuries, firing procedures, warehouse management and projects | 1 October 2021 | Kluge (2021a) |

| Schöneberg and Mitte warehouses join the strike, Gesundbrunnen joins the next day | 2 October 2021 | Kluge (2021b) Partington (2021) Zamora (2021) |

| Wildcat strike takes place | 1–2 October 2021 | Kluge (2021c) |

| Picket lines and blockades disrupt the supply chain | 1–2 October 2021 | Geiger (2021) Kluge (2021a) |

| Demand for schedules to be made for people with real lives | 1–2 October 2021 | Kluge (2021a) Kluge (2021b) Krantz (2021) |

| Mention of life-threatening situations and traffic accidents | 1–2 October 2021 | WSWS (2021) |

| Gorillas hires a private security firm to prevent workers from entering the warehouse, eventually terminating 350 striking workers | 4 October 2021 | Bateman (2021) Hoffmann (2021) Kluge (2021c) Zamora (2021) |

notes: Reasons for protest: occupational injuries from carrying excessive weight, obscure firing procedures, issues with warehouse management, implementation of internal company projects, algorithmically optimized schedules and a need to improve occupational safety (Kluge, 2021a; 2021b; Krantz, 2021).

APPENDIX: ―Sources: vignette Barcelona

| Event | Date | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Rider Law comes into force in Spain | 12 August 2021 | Eurofound (2021) |

| Glovo plans to hire only 20% of their workforce as employees | Alonso (2021) | |

| Glovo introduces ‘multiplier’ in their app | 12 August 2021 | Howells (2021) La Prensa Latina (2021) |

| Reports of requests being transferred to riders with lower multipliers | Editorial TotBarcelona (2021) EFE (2021) López Ruiz (2021) | |

| Glovo denies reports, attributing lower demand to the summer season | López Ruiz (2021) | |

| Protests in front of Glovo's headquarters in Barcelona | 13-16 August 2021 | Crónica Global Editorial (2021) El Punt Avui Editorial (2021) |

| Demands of workers at Glovo supermarkets ignored for months | Wray and Juarez (2021) | |

| Glovo supermarket employees join protests | 17 August 2021 | Catalunyapress (2021) |

| Protests transferred to dark stores | Editorial Metrópoli Abierta (2021) | |

| Glovo reduces the range of the multiplier | 18 August 2021 | Forner (2021) |

| CCOO calls for 9 days of striking in Glovo supermarkets | 23 August 2021 | CCOO (2021b) |

| Workers demand better conditions in warehouses, including toilets, water and lockers | Escofet (2021) | |

| Strikes called by CCOO come to a halt to allow for negotiations with Glovo | 2 September 2021 | CCOO (2021a) |

| Strikes are cancelled | 9 September 2021 | CCOO (2021a) |

- References (2021) Entra en vigor la ley ‘Rider’: qué ocurre con los repartidores en cada empresa [The Rider Law becomes effective: what is happening with the riders of each company] [WWW document]. URL https://www.newtral.es/vigor-ley-rider-repartidores-deliveroo-glovo-ubereats-justeat/20210812/ (accessed 24 January 2023). (2021) Gorillas’ delivery app fires hundreds of Berlin workers for strikes over pay and working conditions [WWW document]. URL https://www.euronews.com/next/2021/10/08/gorillas-delivery-app-fires-hundreds-of-berlin-workers-for-strikes-over-pay-and-working-co (accessed 24 January 2023). Catalunyapress (2021) Els treballadors de Glovo protesten per les seves condicions laborals [Glovo workers protest against their working conditions] [WWW document]. URL https://www.catalunyapress.cat/texto-diario/mostrar/3095526/els-treballadors-glovo-protesten-per-seves-condicions-laborals (accessed 24 January 2023). CCOO (Comisiones Obreras) (2021a) CCOO ajorna la vaga dels supermercats de Glovo dels dies 3, 4 i 5 per donar oportunitat a l'espai de negociació que s'ha obert amb l'empresa després de l’èxit de la vaga del cap de setmana passat [CCOO postpones strike at Glovo supermarkets on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th to provide opportunity for negotiations that opened up with the company after the success of last weekend's strike] [WWW document]. URL https://www.ccoo.cat/noticies/ccoo-ajorna-la-vaga-dels-supermercats-de-glovo-dels-dies-3-4-i-5-per-donar-oportunitat-a-lespai-de-negociacio-que-sha-obert-amb-lempresa-despres-de-lexit-de-la-vag/ (accessed 24 January 2023). CCOO (Comisiones Obreras) (2021b) CCOO convoca 9 dies de vaga als supermercats de Glovo a Barcelona per la millora de les condicions laborals dels seus treballadors i treballadores [CCOO calls for 9 days of strike at Glovo supermarkets in Barcelona for the improvement of the working conditions for employees] [WWW document]. URL https://www.ccoo.cat/noticies/ccoo-convoca-9-dies-de-vaga-als-supermercats-de-glovo-a-barcelona-per-la-millora-de-les-condicions-laborals-dels-seus-treballadors-i-treballadores/ (accessed 24 January 2023). Crónica Global Editorial (2021) Los ‘riders’ protestan contra Glovo en Barcelona por la aplicación de la nueva ley de repartidores [‘Riders’ protest against Glovo in Barcelona over application of new delivery law] [WWW document]. URL https://cronicaglobal.elespanol.com/vida/riders-protestan-contra-glovo-en-barcelona-por-aplicacion-nueva-ley-repartidores_522201_102.html (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2022) Instant grocery app Getir acquires competitor Gorillas [WWW document]. URL https://techcrunch.com/2022/12/09/instant-grocery-app-getir-acquires-its-competitor-gorillas/ (accessed 24 January 2023). Editorial Metrópoli Abierta (2021) Repartidores de supermercados de Glovo en Barcelona paralizan el servicio [Glovo supermarket couriers in Barcelona paralyze the service] [WWW document]. URL https://www.metropoliabierta.com/economia/repartidores-glovo-barcelona-paralizan-servicio_43121_102.html (accessed 24 January 2023). Editorial TotBarcelona (2021) Tres dies de protestes de repartidors de Glovo al centre de Barcelona [Three days of protests by Glovo couriers in the centre of Barcelona] [WWW document]. URL https://www.totbarcelona.cat/economia/tres-dies-de-protestes-dels-repartidors-de-glovo-al-centre-de-barcelona-142351/ (accessed 24 January 2023). EFE (2021) Los ‘riders’ de Glovo denuncian que facturan menos que antes de la ley [Glovo ‘riders’ complain that they invoice less than before the law] [WWW document]. URL https://www.diariodesevilla.es/economia/riders-glovo-denuncian-aplicacion-nueva-reduce-sus-ingresos_0_1602140583.html (accessed 24 January 2023). El Punt Avui Editorial (2021) Protesta dels ‘riders’ contra el nou model de tarifes de Glovo [Protest of ‘riders’ against the new Glovo rate model] [WWW document]. URL https://www.elpuntavui.cat/societat/article/5-societat/2015548-protesta-dels-riders-contra-el-nou-model-de-tarifes-de-glovo.html (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Glovo Market: què son i com funcionen els supermercats de l'empresa a Barcelona [Glovo Market: what are they and how do the supermarkets of the company function in Barcelona? [WWW document]. URL https://beteve.cat/economia/glovo-market-barcelona-que-son-com-funcionen/ (accessed 18 August 2022). Eurofound (2021) Rider's Law [WWW document]. URL https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/nl/data/platform-economy/initiatives/riders-law (accessed 5 April 2022). . (2021) Red flag: union busting in Berlin [WWW document]. URL https://www.exberliner.com/politics/gorillas-berlin-union-strike/ (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Glovo rectifica su algoritmo tras las protestas de riders de Barcelona [Glovo rectifies their algorithm after rider protests in Barcelona] [WWW document]. URL https://www.elsaltodiario.com/glovo/glovo-rectifica-su-algoritmo-tras-protestas-riders-barcelona (accessed 18 August 2022). . (2021) Gorillas delivery app fires workers for striking [WWW document]. URL https://www.vice.com/en/article/7kvgmd/gorillas-delivery-app-fires-workers-for-striking (accessed 6 September 2022). and (2021) La ‘Ley Rider’ hace aguas y solo Just Eat contratará a sus repartidores [The ‘Rider Law’ fails and only Just Eat will hire its couriers] [WWW document]. URL https://www.eleconomista.es/empresas-finanzas/noticias/11355709/08/21/La-Ley-Rider-hace-aguas-y-solo-Just-Eat-contratara-a-sus-repartidores.html (accessed 24 January 2023). Gorillas.io (2022) Gorillas celebrates 16 million orders worldwide [WWW document]. URL https://web.archive.org/web/20240313102255/https://gorillas.io/en/blog/gorillas-celebrates-16-million-orders-worldwide (accessed 13 June 2024). . (2021) ‘Ganz ohne Vorwarnung ist das schwierig’ [‘It's difficult without any prior warning’] [WWW document]. URL https://www.spiegel.de/karriere/gorillas-streik-sorgt-fuer-fristlose-kuendigung-als-faustregel-gilt-ganz-ohne-vorwarnung-ist-das-schwierig-a-86876fc0-8557-4ed1-b683-971d61e5f912 (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Glovo delivery drivers stage fourth day of protests in Barcelona over lower pay [WWW document]. URL https://euroweeklynews.com/2021/08/17/glovo-delivery-drivers-stage-fourth-day-of-protests-in-barcelona-over-lower-pay/ (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021a) Arbeitskampf beim Berliner Start-up: streikende Gorillas-Rider legen zwei Lagerhäuser lahm [Industrial action at Berlin start-up: striking Gorillas riders bring two warehouses to a standstill] [WWW document]. URL https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/streikende-gorillas-rider-legen-zwei-lagerhauser-lahm-4281319.html (accessed 30 August 2022). . (2021b) Lieferdienst kommt nicht zur Ruhe: Gorillas-Rider streiken wieder in Berlin [Delivery service can't rest: Gorillas riders on strike again in Berlin] [WWW document]. URL https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/lieferdienst-kommt-nicht-zur-ruhe-gorillas-rider-streiken-wieder-in-berlin-269386.html (accessed 20 September 2022). . (2021c) Arbeitskampf in Berlin eskaliert: Start-up Gorillas entlässt streikende Fahrradkuriere [Labour struggle in Berlin escalates: Gorillas start-up dismisses striking bicycle couriers] [WWW document]. URL https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/start-up-gorillas-entlasst-streikende-fahrradkuriere-4282297.html (accessed 24 January 2023). (2021) Germany: Gorillas delivery riders protest unfavorable working conditions [WWW document]. URL https://www.dw.com/en/germany-gorillas-delivery-riders-protest-unfavorable-working-conditions/a-58325911 (accessed 24 January 2023). labournet.tv (2021) Gorillas strike at Bergmannkiez. Video [WWW document]. URL https://en.labournet.tv/gorillas-strike-bergmannkiez (accessed 20 September 2022). (2021) Glovo riders protest against changes to app charging system [WWW document]. URL https://www.laprensalatina.com/glovo-riders-protest-against-changes-to-app-charging-system/ (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Els sindicats acusen Glovo de donar les comandes als ‘riders’ que accepten cobrar menys [Unions accuse Glovo of giving orders to ‘riders’ who agree to charge less] [WWW document]. URL https://beteve.cat/economia/nova-protesta-contra-glovo-sindicats-acusen-donar-comandes-riders-accepten-preu-mes-baix/ (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Gorillas founder talks of ‘terminating’ employee attempting to unionise, according to leaked internal Slack [WWW document]. URL https://sifted.eu/articles/gorillas-workers-tensions/ (accessed 24 January 2023). and (2021) On-demand grocery delivery startup Gorillas raises €245m and becomes a unicorn, nine months after launch [WWW document]. URL https://sifted.eu/articles/gorillas-raises-e245m-unicorn/ (accessed 20 August 2021). . (2021) Un nuevo conflicto laboral cerca a Glovo: arranca la huelga en sus supermercados de Barcelona [A new labour conflict closes in on Glovo: the strike in its Barcelona supermarkets begins] [WWW document]. URL https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/nuevo-conflicto-laboral-cerca-glovo-arranca-huelga-supermercados-barcelona_1_8248052.html (accessed 11 June 2024). . (2022a) A message from co-founder and CEO Kagan Sümer [WWW document]. URL https://gorillas.io/en/blog/a-message-from-co-founder-and-ceo-kagan-sumer (accessed 11 June 2024). . (2022) Manifesto [WWW document]. URL https://web.archive.org/web/20240301143559/https://gorillas.io/en-us/manifesto (accessed 6 June 2024). and (2021) Gig economy project—organising riders in Barcelona: interview with CCOO's Carmen Juares [WWW document]. URL https://braveneweurope.com/gig-economy-project-organising-riders-in-barcelona-interview-with-ccoos-carmen-juares (accessed 16 August 2022). WSWS (World Socialist Web Site) (2021) Resistance spreads among German delivery service workers [WWW document]. URL https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2021/08/17/deli-a17.html (accessed 24 January 2023). . (2021) Gorillas in unlimited strike [WWW document]. URL https://www.klassegegenklasse.org/gorillas-in-unlimited-strike/ (accessed 24 January 2023).

Biographies

Nicolás Palacios Crisóstomo, ETH Zürich, Spatial Development and Urban Policy (SPUR), Zürich, Switzerland, [email protected]

David Kaufmann, ETH Zürich, Spatial Development and Urban Policy (SPUR), Zürich, Switzerland, [email protected]

References

- 1 Advertised as 10-, 15-, 30- or 60-minute delivery services.

- 2 These data were checked monthly over the period of a year by the authors on the Gorillas website.

- 3 This is not to be confused with the urban strategy present in the urban revolution, which, according to Schmid (2022: 492), is ‘a strategy of self-organization and urban autogestion’.

- 4 Deleuze and Guattari also developed the concepts of deterritorialization and reterritorialization.

- 5 See Appendix 1; 16 were directly cited.

- 6 See Appendix 2; 19 were directly cited.

- 7 Data sourced from Gorillas.io, by visiting their delivery areas section monthly for a year.

- 8 See labournet.tv (2021), Gorillas strike at Bergmannkiez. Video [WWW document]. URL https://en.labournet.tv/gorillas-strike-bergmannkiez (accessed 20 September 2022).