The social meanings of PrEP use – A mixed-method study of PrEP use disclosure in Antwerp and Amsterdam

Abstract

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) is a novel HIV prevention tool. PrEP stigma is a frequently reported barrier, while social disclosure of PrEP use may be an important facilitator. We explored how PrEP users managed PrEP use disclosure using a symbolic interactionist approach. We interviewed 32 participants from two PrEP demonstration projects (Be-PrEP-ared, Antwerp; AMPrEP, Amsterdam). We validated qualitative findings through Be-PrEP-ared questionnaire data. A minority of participants had received negative reactions on PrEP. The way PrEP use was disclosed was highly dependent on the social situation. In a sexual context among MSM, PrEP use was associated with condomless sex. Friends endorsed PrEP use as a healthy choice, but also related it to carelessness and promiscuity. It was seldom disclosed to colleagues and family, which is mostly related to social norms dictating when it is acceptable to talk about sex. The study findings reveal that PrEP stigma experiences were not frequent in this population, and that PrEP users actively manage disclosure of their PrEP user status. Frequent disclosure and increased use may have helped PrEP becoming normalised in these MSM communities. To increase uptake, peer communication, community activism and framing PrEP as health promotion rather than a risk-reduction intervention may be crucial.

Abbreviations

-

- AVAC

-

- AIDS vaccine Advocacy Coalition

-

- HIV

-

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus

-

- IDI

-

- In-depth interview

-

- LGBTI

-

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex

-

- MSM

-

- Men who have sex with men

-

- PrEP

-

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

-

- STI

-

- Sexually Transmitted Infection

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION

Since 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for individuals at substantial risk of HIV infection (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2015). Demonstration projects and open-label studies showed that PrEP provision is feasible as part of a combination prevention approach among key populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) (Grinsztejn et al., 2018; Hoornenborg et al., 2019; McCormack et al., 2015; Molina et al., 2015; Vuylsteke et al., 2019; Zablotska et al., 2019). Since the WHO recommendation, the number of countries rolling out PrEP has been increasing, most rapidly in Western Europe (AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition (AVAC), 2020). But, if and how it will be used partially depend on its social acceptability as HIV prevention strategy (Haire, 2015).

The clinical efficacy of this novel biomedical tool was demonstrated in various clinical trials (Fonner et al., 2016). Since the start, there has been much focus on the potential impact of PrEP on sexual behaviour, that PrEP may lead to increased risk-taking or condomless sex (Holt & Murphy, 2017; Rojas Castro et al., 2019). Other research focusing on the ‘behavioural aspects’ of PrEP mostly focused on factors that may influence the effectiveness of PrEP, such as barriers to uptake and adherence. Survey studies have attempted to quantify the level of awareness and acceptability of PrEP among ‘at-risk populations’ such as MSM (Peng et al., 2018). Qualitative studies reveal barriers such as ‘PrEP stigma’ due to its associations with promiscuity, HIV and homosexuality (Brooks et al., 2019a, 2019b; Calabrese & Underhill, 2015; Collins et al., 2017; Grace et al., 2018; Haire, 2015; Newman et al., 2018; Pawson & Grov, 2018; Puppo et al., 2020). Disclosing PrEP use to others can lead to social support and is thus deemed an important facilitator for PrEP use (Brooks et al., 2019a; Phillips et al., 2019).

In this study, we focus on the social meaning of PrEP. According to symbolic interactionism, the meaning of something is not intrinsic to the object, nor is it defined by our attitude towards it. Instead, meanings are social products that are formed in and through social interaction (Blumer, 1969). Through language and behaviour, we derive how others may or will act towards the object or person, which helps to adapt our own actions accordingly. The social meanings attached to PrEP will co-determine how it is used (Auerbach & Hoppe, 2015), and how PrEP users are perceived within society. For example, if PrEP is perceived to be for high-risk individuals, it provides a discourse for labelling PrEP users as sexual deviants (Pawson & Grov, 2018) and is likely to prevent people from using it (Holt, 2015). Moreover, studying the social meaning of PrEP can help us understand the impact PrEP may have on individuals, sexual cultures or even society at large. How PrEP users are perceived within a given culture may determine what potential sex partners can expect from sexual encounters. Claiming to be a PrEP user can shape interactions with sex partners, friends and family (Auerbach & Hoppe, 2015). The sheer existence of PrEP may lead to prevention optimism, that is individuals believing the risk of getting infected with HIV is lower in their community (Holt & Murphy, 2017).

We draw upon symbolic interactionism to study the social meaning of PrEP, more specifically the work of H. Blumer (Blumer, 1969). A first premise in symbolic interactionism is that people act towards things on the basis of the meaning that these things have to them. For example, a pill to reduce the risk for acquiring HIV will more likely be used by those perceiving themselves at risk for HIV infection. A second premise is that such meanings are derived through social interaction. It is through others that we learn that PrEP is for ‘promiscuous persons’ or that PrEP is ‘a responsible choice’. PrEP is a relatively new HIV prevention tool, and its presence in everyday life has only increased during the last few years, making it ideal to study how individuals have come to derive its social meaning through social interaction. Thirdly, these social meanings are handled in and modified through an interpretative process. PrEP users are not merely passive recipients of PrEP stigma, but such meanings are interpreted, handled within a social situation, and can be acted upon by an individual. Symbolic interactionism is particularly helpful to understand how the meaning of something, in this case PrEP, is being defined and re-defined in everyday social life. In this empirical approach, the focus is on the perceiving individual who adapts his/her behaviour based on his/her perceptions. Hence, it is an ideal lens to study how individuals learn about PrEP through others and how they adapt their behaviour accordingly.

Social meanings are never fixed, but constantly negotiated through a ceaseless stream of social interaction (Plummer, 1982). To better understand the social meaning of PrEP use, we must explore how it is derived, interpreted, negotiated and potentially changed through social interaction. Therefore, in this study, we also focus on disclosure of PrEP use. Focussing on social disclosure enables a micro-level view on how the social aspects of PrEP use are handled in everyday life. Various studies have reported ‘PrEP stigma’, meaning that PrEP is socially discredited and confers negative judgement or value onto the individual (Golub, 2018; Siegler et al., 2020). Distinctions are made between experienced, perceived, anticipated or internalised stigma (Rosengren et al., 2021). But how individuals deal with such potential stigma in everyday life is not yet fully understood. These studies or reviews frequently refer to the concept ‘stigma’ of symbolic interactionist E. Goffman (Goffman, 1963). But, the most central idea of Goffman, that individuals present themselves to others in order to shape others' perceptions of oneself (Goffman, 1959), is frequently missing in qualitative PrEP research. As presented in the work of G.H. Mead (Mead, 1934), social interaction not only involves an individual perceiving oneself through the other, but also the exertion of behaviour in such a way that the others' attitudes towards oneself are shaped. PrEP is a pill that can be taken privately most of the time, which means that disclosure of PrEP use can be selective (Phillips et al., 2019). Hence, exploring why, when and how PrEP use may or may not be disclosed provides an ideal opportunity to study how the social meaning of PrEP is handled to shape others' perceptions of oneself.

The main objective of this study was to explore how early adopters of PrEP in Belgium and the Netherlands experienced and managed PrEP disclosure to others. Such knowledge will be important to fully understand how social interaction and social life can influence its uptake, its use, and how PrEP is becoming part of the social and sexual culture of MSM communities, and society at large.

METHODS

Study design

The study adopted a concurrent [QUAL+quan] mixed method design, using a grounded theory approach (Johnson & Christensen, 2008; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We conducted the study in two settings where comparable PrEP demonstration projects were ongoing: the Be-PrEP-ared study in Antwerp, Belgium, and the Amsterdam PrEP study (AMPrEP) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Detailed study procedures and main results of Be-PrEP-ared and AMPrEP were published elsewhere (De Baetselier et al., 2017; Hoornenborg et al., 2018, 2019; Reyniers et al., 2018; Vuylsteke et al., 2019; Zimmermann et al., 2019). In both studies, MSM and transgender persons at high risk of HIV infection (200 in Antwerp and 376 in Amsterdam) initiated PrEP. Participants were able to choose and switch between daily and event-driven PrEP regimens. During quarterly visits in two clinics (Antwerp and Amsterdam), study procedures included sexual health and adherence counselling, testing for HIV and other STIs, and completion of a questionnaire.

The qualitative strand of this study included in-depth interviews conducted as part of Be-PrEP-ared and AMPrEP. A qualitative research team of four social scientists (TR, CN, HZ and UD) conducted data collection and analysis. The quantitative strand used questionnaire data from Be-PrEP-ared.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data were collected and analysed iteratively, following a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In-depth interviews provide an ideal starting point to investigate how social meanings are derived, handled and acted upon from the standpoint of individuals (Blumer, 1969). Be-PrEP-ared participants were selected as part of the main Be-PrEP-ared study, based on information-rich events (e.g. switching regimen or stopping with PrEP) or availability, that is before or after a follow-up visit (De Baetselier et al., 2017). We conducted in-depth interviews with AMPrEP participants who either had disclosed PrEP use to almost nobody, and participants who had disclosed to a wide range of persons, based on their answers in the AMPrEP questionnaire. During the data collection phase, the topic guide was adapted slightly, without losing consistency, to explore emerging themes in-depth, based on preliminary analyses.

Two social scientists (TR and CN) conducted the Be-PrEP-ared interviews. One social scientist TR conducted the AMPrEP interviews for this study. The interviews took place in a confidential and safe place within the clinic of each study site. A comparable topic guide was used in both study sites, with one identical section on social disclosure of PrEP use. In line with symbolic interactionist theory (Blumer, 1969), we discussed with participants how they perceived PrEP use and, how it was perceived by others, which reactions they received after disclosing their PrEP use and how such disclosure differed according to social situations. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

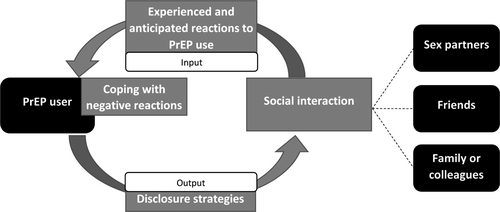

The data were analysed in three consecutive phases using NVIVO 12. Analyses were discussed within the research team in between each phase. A coding scheme was developed inductively while coding 15 Be-PrEP-ared interviews, with the focus on finding patterns in experiencing and managing disclosure of PrEP use. The scheme was adapted after analysing 10 additional AMPrEP interviews, in which disclosure experiences, strategies used by participants and differences according to social situations were categorised. The third phase involved re-analysing all interviews with the remaining eight Be-PrEP-ared interviews, with the purpose of developing an explanatory framework (see Figure 1). The explanatory framework is guided by symbolic interactionist principles: it provides an overview of how social meanings are derived, managed and acted upon through social interaction by focusing on social disclosure in different social situations.

Quantitative data

Details on the development and use of the questionnaires were published elsewhere (De Baetselier et al., 2017; Hoornenborg et al., 2018, 2019; Vuylsteke et al., 2019). We used sociodemographic data of the baseline questionnaires completed at the start of both Be-PrEP-ared and AMPrEP to provide an overview of the study samples and the participants interviewed. All other quantitative data used are from Be-PrEP-ared. Every 3 months, participants were asked to indicate who they had disclosed PrEP use to, with different answering options (e.g. casual sex partners). The Be-PrEP-ared end-of-study questionnaire included questions regarding the experiences of PrEP disclosure. These items were developed based on the preliminary analysis of the interviews. Be-PrEP-ared participants completed the end-of-study questionnaire during their last visit, between follow-up months 18 and 27. The quantitative data were descriptively analysed.

Ethical approval

The Be-PrEP-ared study received ethical approval of the institutional review board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp) and the Ethical Committee of the Antwerp University Hospital. The AMPrEP study received ethical approval from the ethics board of the Amsterdam UMC at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

RESULTS

We interviewed 32 participants between January 2016 and April 2018. Interviewees were comparable to the overall study sample, but were more likely to be higher educated (Table 1). Be-PrEP-ared interviewees were less likely to have a steady partner, while AMPrEP interviewees were more likely to be older and to identify as exclusively homosexual.

| Baseline characteristics | Be-PrEP-ared | AMPrEP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study cohort N = 200 |

IDI sample N = 22 |

Study Cohort N = 376 |

IDI sample N = 10 |

|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Median age | 38 years | 37 years | 39 years | 45 years |

| Male | 197 (98.5) | 22 (100.0) | 374 (99.5) | 10 (100.0) |

| Born as Belgian/Dutch | 156 (78.0) | 16 (72.7) | 295 (78.5) | 8 (80.0) |

| White | 178 (89.0) | 19 (86.4) | 315 (85.1) | 8 (80.0) |

| Higher education | 155 (77.5) | 20 (90.1) | 286 (76.1) | 10 (100.0) |

| Steady partner | 90 (45.0) | 4 (18.2) | 164 (44.1) | 5 (50.0) |

| Living alone | 100 (50.0) | 14 (63.6) | 200 (53.9) | 6 (60) |

| Exclusively homosexual | 144 (72.0) | 17 (77.3) | 296 (78.7) | 10 (100.0) |

- Abbreviation: IDI, in-depth interview.

Overview of the findings

Figure 1 shows the explanatory framework derived from the triangulated qualitative and quantitative findings. It shows the cyclical manner in which two social processes operate through social interaction from the PrEP user perspective: anticipating or experiencing how others see PrEP users (‘input’) and managing PrEP use disclosure (‘output’). We describe these processes first. Next, we describe how these processes can vary according to social relation(s) present when interacting socially: sex partners, friends, and family or colleagues. Quantitative findings are presented after qualitative results.

Through social interaction, participants learned how others perceived PrEP or a PrEP user, and its associations, that is the social meanings of PrEP use (‘input’, Figure 1). The narratives reveal how others reacted when PrEP use was disclosed. They show how specific reactions were anticipated based on earlier experiences. Interviewees differed in the way they coped with negative reactions.

When interacting socially, participants used different strategies to disclose their PrEP use or to withhold such information (‘output’, Figure 1). Disclosing PrEP use was highly dependent on the anticipated reactions, the type of social relation and the social meaning of PrEP within the social situation. We found that interviewees were selective in disclosing PrEP use. When there was no valid reason from their point of view, PrEP use was usually not disclosed actively.

Experienced reactions to PrEP use disclosure

Rather neutral. It's not like <Whoaw you're taking that? Super! > It's more like <OK, good for you>. (Interviewee 12; Be-PrEP-ared)

In most cases, [reactions are] very positive. I've heard a few times that they are glad to hear that I'm trying to protect myself and that I'm trying to take as few risks possible. (Interviewee 13, Be-PrEP-ared)

It has changed, it has gone very quick. It's a very nice period of time to see what two years of PrEP use and PrEP information has done […]. I'm talking about the beginning where people within the gay community were very critical about [PrEP], up until the moment where, well yeah, people start using it and the information got going. (Interviewee 7, AMPrEP)

In the Be-PrEP-ared questionnaire, participants indicated to what extent they had received negative remarks regarding their PrEP use: 57 (54.8%) indicated none, 25 (24.0%) only once, 19 (18.3%) a few times and 3 (2.9%) regularly. Negative reactions were from someone they knew (46.8%), someone online (46.8%), someone they met (21.3%), a close friend (19.1%), family (4.3%), a colleague (4.3%) or partner (2.1%).

Anticipated reactions to PrEP use disclosure

Well, I think my mother would have an anger or panic attack. We don't talk about me being gay, she's on a whole different level in terms of acceptance. (Interviewee 9; AMPrEP)

Coping with negative reactions

It does not affect whether I'm taking [PrEP] because I just do it. It does affect who I tell about PrEP, but not whether I'm using it more or less. (Interviewee 5, AMPrEP)

I've had a conversation about it a few times, in the beginning, with people stating that PrEP users are HIV positive or only have bare sex. You have to explain that a bit, there is a lack of information. (Interviewee 17, Be-PrEP-ared)

Among those indicating having received negative reactions in the end-of-study questionnaire, 29 (61.7%) indicated that this did not really or not at all bother them; it did bother 13 (27.7%) participants; and for 5 (10.6%) it bothered them a lot (data not in table).

Disclosure strategies

Well, actually [I tell that I'm using PrEP] to anyone who wants to know. I'm not going to run around […] to tell everyone, but as soon as there is a reason to do so, I tell them. (interviewee 7, AMPrEP)

There are a number of people, and there are a number of situations where you think like <well, they don't have to know [that I'm using PrEP]>. And then I retreat for a short time, a bit of water and [I take my PrEP pill]. (interviewee 1, AMPrEP)

I like telling people about PrEP, because I think, everyone, all gay people should be using PrEP. It's a way of advocating for the cause. But it's difficult when a lot of people don't know what PrEP is and then you have to explain. (interviewee 10, AMPrEP)

Disclosure to sex partners

Last week I told someone that I was taking part in the study <I take PrEP> and he seemed to know what I was talking about. He said <Ah okay, then we don't need to use a condom>. (interviewee 5, Be-PrEP-ared)

I can put it [in my online profile] and then I really attract people who are looking for the same thing. And to raise my chances. (interviewee 20, Be-PrEP-ared)

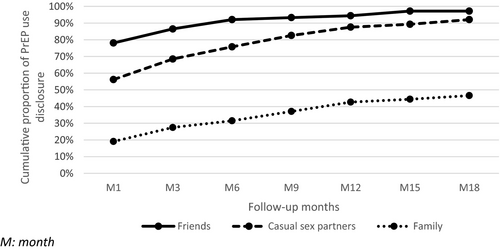

Among Be-PrEP-ared participants, 100 (56.2%) had disclosed PrEP use to at least one casual sex partner in the first month of PrEP use, and 156 (87.6%) did so within the first year (Figure 2).

Disclosure to friends

Some friends know about [my PrEP use] but they condemn it a bit: <Oh no, you're not going to [do that] are you?, it costs a lot of money > that kind of things, you know. [They said PrEP users are] prostitutes, they are irresponsible and they spread STIs. (interviewee 4, AMPrEP)

However, positive reactions in this social context included that PrEP was also associated with being responsible or as taking care of one's health. In the latter case, PrEP use was endorsed by friends or generated curiosity.

Among Be-PrEP-ared participants, 139 (78.1%) had disclosed PrEP use to a friend in the first month of PrEP use, and 168 (94.4%) within the first year (Figure 2).

Disclosure to family and colleagues

I have not told my parents because […] in order to properly justify PrEP use to them, I would have to explain my sex life. […] It's not something you discuss with your parents. It's my private sexual sphere […],you have to [explain] that you have sex outside of the relationship, you frequently have sex, you have sex with multiple partners at the same time. (Interviewee 16, Be-PrEP-ared)

Some interviewees anticipated judgemental reactions about promiscuity or worrisome reactions towards HIV. Other interviewees explained that they did not disclose to family members as they generally do not discuss gay-related matters with them. Therefore, PrEP use was less likely to be disclosed in these situations. Some interviewees had disclosed to a particular family member or colleague, and usually explained that in these instances they had a close relationship with this person.

Among Be-PrEP-ared participants, 34 (19.1%) had disclosed PrEP use to a family member in the first month, and 76 (42.7%) within the first year (Figure 2). Twelve participants (0.7%) had disclosed PrEP use to a colleague in the first month; this had not changed after 1 year.

DISCUSSION

We explored how participants from two PrEP demonstration projects in Antwerp, Belgium (Be-PrEP-ared) and Amsterdam, the Netherlands (AMPrEP) experienced and managed disclosure of their PrEP use. In line with the symbolic interactionist approach, we not only focused on how participants learned how others view PrEP users, but also how they actively manage their PrEP users status and negotiate the social meaning of PrEP through social interaction. The majority of Be-PrEP-ared participants had not received negative reactions towards their PrEP use over a period of at least 18 months. Interviewees adopted different strategies to avoid or to cope with such negative reactions, for instance by being selective about whom they would disclose PrEP to or correcting misconceptions about PrEP use. PrEP use disclosure was dependent on the social relation and context (e.g. a sex partner, friend or family member). Among MSM and potential sex partners, PrEP use was generally associated with condomless sex. PrEP use was generally not disclosed to family members or colleagues, as sexuality is usually not discussed within these social contexts. Among friends, PrEP use was endorsed because of its potential health benefit, but was also criticised as being careless and promiscuous.

An important finding is that within the first year of PrEP use almost all Be-PrEP-ared participants had told friends or sexual partners about their PrEP use. Only a minority (21.2%) indicated to have experienced more than one negative reaction with regard to their PrEP use after 18 months. This is in contrast to other studies, including two reviews, underscoring that PrEP use is stigmatised (Collins et al., 2017; Dubov et al., 2018; Golub, 2018; Grace et al., 2018; Haire, 2015; Newman et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019; Maria Van Der Elst et al., 2013), but in line with one study from the USA showing that PrEP stigma may be low (Siegler et al., 2020).

Participants in our study experienced few difficulties with disclosing their PrEP use. The symbolic interactionist approach used in this study can provide two explanations for this finding. The first lies in the selective nature in which PrEP users may or may not choose to disclose their PrEP use in everyday social life, as found elsewhere (Brooks et al., 2019a; Newman et al., 2018; Puppo et al., 2020). This implies that the impact on PrEP use may be limited, as supported by our qualitative data. Situations in which PrEP use may be publicly disclosed, such attending the clinic, were generally not seen as problematic among the interviewees in our study. Interviewees reported that pill intake can be hidden if needed. However, we also found that some PrEP users might experience difficulties, for example taking PrEP in presence of a steady partner who did not approve of the PrEP use. Some PrEP users may be more likely to experience difficulties in hiding their pills, such as young MSM living at home, those living with a female partner, or those living a social environment that is less positive towards homosexuality (Brooks et al., 2019a; Haire, 2015; Mustanski et al., 2018; Siegler et al., 2020; Witzel et al., 2019). Future research could explore whether long-acting PrEP modalities, such as injectables, may overcome such difficulties.

The second possible explanation lies in the transformative potential of social interaction, in combination with activism within MSM communities. Social meanings are derived through social interaction with others, but are never fully fixed (Blumer, 1969). Social meanings thus can also be transformed through social interaction. Interviewees' narratives show that the social meaning of PrEP had changed over the past few years, due to increased sensibilisation and more widespread use and knowledge about PrEP, as reported elsewhere (Thomann et al., 2018). Within MSM communities, there has been advocacy early on to counteract negative perceptions, such as activists wearing the label ‘truvada whore’ with pride (Auerbach & Hoppe, 2015; Race, 2017). But also PrEP users themselves, in particular early adopters, may have been instrumental in normalising PrEP within MSM communities. This is evidenced by interviewees who actively disclosed PrEP use to others to inform them about its existence, or counter-acted negative reactions, as found in other qualitative studies (Brooks et al., 2019a; Card et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019). A similar recent study in the USA also documented that widespread use and disclosure of PrEP had normalised it into an everyday practice, while early adopters actively promoted PrEP use to peers and combated stigma (Gómez et al., 2020). Hence, stimulating peer communication about PrEP use and sharing positive narratives around PrEP may be important strategies to further increase PrEP uptake. This could be achieved by underscoring, for instance, that PrEP can be a healthy, responsible choice, rather than something for individuals ‘at risk’ (Golub, 2018; Rojas Castro et al., 2019), or that PrEP can enable users to have more enjoyable sexual encounters (Mabire et al., 2019; Race, 2017; Reyniers et al., 2021; Zimmermann et al., 2020).

Our findings suggest that the PrEP narrative has spread quickly in the MSM communities in this study. The work of K. Plummer can provide additional insights as to why this may have been the case, here conveniently summarised as ‘Stories can be told when they can be heard’ (Plummer, 2002). Before PrEP was available, it was frequently argued that MSM communities in high-income countries would experience ‘prevention fatigue’, explaining reduced condom use (Spire et al., 2008). Such a community may have been more supportive of PrEP use, and at the same time, through a shared sense of community, PrEP disclosure and advocacy may have further strengthened community building. The introduction of PrEP may have also led to opportunities for opening up the conversation about such prevention fatigue and to be responsive to particular needs, such as combining sex and drugs (Nicholls & Rosengarten, 2020; Race, 2017). Furthermore, it should be noted that Belgium and the Netherlands (the focus of this study) are countries with relatively good LGBTI-friendly policies (ILGA-Europe, 2020), where MSM experience less gay-related verbal discrimination or physical violence (Ross et al., 2013), and report less internalised homonegativity (Tran et al., 2018), when compared with other European countries. In countries with a less LGBTI-friendly climate, MSM might experience more negative reactions when disclosing their PrEP use, and peer communication about PrEP may prove to be more difficult.

In a sexual context, PrEP use was generally associated with condomless sex in our sample, corroborating findings from other studies (Card et al., 2019; Grace et al., 2018; Puppo et al., 2020). Despite efforts and recommendations of providing PrEP as an additional tool in a combination prevention strategy (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2015), many MSM may be viewing PrEP as a replacement for condoms. This can undermine PrEP users' abilities to negotiate the use of condoms when preferring one (Puppo et al., 2020). It shows that the relation between condom and PrEP use remains ambiguous, and that we lack an unanimous perspective and a clear message or narrative on how they could be related to each other (Holt et al., 2019).

We found that interviewees did not often disclose PrEP use to family members and colleagues, as also reported by other qualitative research (Witzel et al., 2019). The quantitative follow-up data showed that after 1 year 42.7% of Be-PrEP-ared participants had disclosed PrEP to at least one family member. Our qualitative findings revealed that in the family context sexuality was not an acceptable or relevant topic of conversation, therefore, disclosing PrEP use was not seen as beneficial. However, this is not equal to PrEP use being stigmatised in these situations. Social norms prescribe when it is acceptable to talk about sex (Cislaghi & Shakya, 2018), and for most of our participants, this did not include the family context. We suggest that further research should disentangle not disclosing due to social norms prescribing when it is acceptable to talk about sex from not disclosing PrEP due to anticipated stigma. For example, when developing a PrEP stigma scale (Siegler et al., 2020), it can be questioned whether indicating that family members are not supportive of PrEP use should be seen as sign of stigma.

Interviewees experienced and anticipated negative reactions towards PrEP due to the association of PrEP with promiscuity, as found elsewhere (Grace et al., 2018; Puppo et al., 2020). A subgroup of MSM, and more particular MSM using PrEP, can have multiple casual sex partners independent of being in a steady relationship (Basten et al., 2018; Bochow et al., 1994; Hess et al., 2017; Hoornenborg et al., 2019; Kramer et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2012; McCormack et al., 2015; Molina et al., 2017; Reyniers et al., 2018). These negative reactions to having multiple sex partners show that the heterosexual monogamy norm remains dominant in society (Worth et al., 2002), and that PrEP is a visible marker for violating this norm. However, as PrEP is becoming part of MSM communities, its sheer existence and association with having multiple sex partners may also mean that non-monogamy has become or is becoming a norm within MSM communities (Philpot et al., 2018).

The symbolic interactionist approach showed how the social meaning of PrEP can vary between social contexts and how disclosure is managed accordingly. Due to its empirical focus on individual perceptions and behaviour of acting individuals, it is particularly helpful to understand how disclosure of using a potentially stigmatised health intervention is managed in everyday social life. The approach and the explanatory framework may be relevant to study other potentially stigmatised illnesses (e.g. mental health illness) and to find strategies to cope with social disclosure of such illnesses. For example, studies suggest stigma is an important concern for people with depression, and disentangle different types such as ‘personal’, ‘public’ or ‘self-stigma’ (Griffiths et al., 2008). A symbolic interactionist approach could help understand how, from an individual standpoint, such meanings are dealt with in everyday life. Moreover, the approach can be useful to study how the social meaning of a particular illness or health-promoting intervention may vary across social contexts. Understanding such variations can be crucial to understand why a particular intervention may (not) work in a given setting while its efficacy has been demonstrated elsewhere, or to help explain regional differences in public health programs or health-promotion interventions (Moore et al., 2015).

Limitations

The sample size and the qualitative nature of the research findings limit generalisability of the findings, but provide in-depth insights into the disclosure of PrEP use among MSM. Stigma experiences and restricted disclosure of PrEP use may be more frequent in countries and social environments where MSM experience more internalised homonegativity. Participants were early PrEP adopters taking part in a demonstration project to assess the feasibility of providing PrEP to MSM within these setting. Hence, they may have been more willing to use PrEP, which can be associated with having less PrEP stigma (Siegler et al., 2020). Participants were predominantly white and higher educated, which may also limit generalisability to other MSM communities. The interviewees were more likely to identify as exclusively homosexual, and no transgender persons were interviewed which should be taken into account when interpreting the qualitative findings. Transgender persons and men who do not self-identify as homosexual (e.g. bisexual men) may be more likely to experience negative or stigmatising reactions. The interviewees from Amsterdam were selected for having disclosed to either a wide range of persons, or to nobody, whereas we did not use such criteria in Antwerp. This may imply that we were more likely to find differences in disclosure strategies. However, we did not find substantial differences between the two sites in that regard.

CONCLUSION

Among early PrEP adopters in Belgium and the Netherlands, disclosure of PrEP use was high, in particular to friends and sex partners. PrEP users anticipated and received negative reactions about their PrEP use, leading them to being selective about whom to disclose PrEP use to. Stigma and negative reactions seemed to have little impact on PrEP use. In a sexual context, PrEP use was associated with condomless sex, which supports the notion that PrEP is replacing condom use in a sub-group of MSM. Increasing PrEP use, sensibilisation, and advocacy by early adopters may have contributed to the normalisation of PrEP among MSM communities in these settings. To increase uptake among those with an unmet PrEP need, peer communication, community activism and framing PrEP as health promotion rather than a risk-reduction intervention may be crucial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all Be-PrEP-ared and AMPrEP participants. We thank the Be-PrEP-ared study group, laboratory staff and the Community Advisory Board. We thank the AMPrEP study group, the members of the AMPrEP advisory board and community engagement group, and all of those who contributed to the H-TEAM.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Thijs Reyniers: Conceptualization (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Methodology (lead); Writing-original draft (lead); Writing-review & editing (lead). Hanne M. L. Zimmermann: Conceptualization (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Udi Davidovich: Conceptualization (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Bea Vuylsteke: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Marie Laga: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Elske Hoornenborg: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Maria Prins: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Henry J. C. De Vries: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Christiana Nöstlinger: Conceptualization (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (equal); Writing-review & editing (supporting).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.