Autonomy, Power and the Special Case of Scarcity: Consumer Adoption of Highly Autonomous Artificial Intelligence

Abstract

Unlike previous generations of artificial intelligence (AI), AI assistants today can autonomously perform actions without human input or intervention. Several studies have proposed but not tested the notion that increased levels of AI autonomy may ultimately conflict with consumers’ fundamental need for autonomy themselves. Across five experiments (N = 1981), including representative samples and pre-registered hypotheses, we investigate consumer responses to high (vs. low) AI autonomy in the context of online shopping. The results show a pronounced negative effect of high AI autonomy on consumers’ adoption intentions – an effect mediated by consumers’ relative state of powerlessness in the presence of high AI autonomy. However, when consumers face situations characterized by scarcity, such as when preferred options are being sold out rapidly (e.g. Black Friday), the aversive aspects of high (vs. low) AI autonomy are attenuated. Together, these findings offer novel insights regarding whether, when and why consumers are willing to adopt high (vs. low)-autonomy AI assistants in online shopping settings.

Less is more… how can that be? It's impossible… more is more.

Yngwie Malmsteen – multi-instrumentalist

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful assistive technology that challenges what managers and scholars know about consumer responses, considering the many novel ways AI assistants can facilitate consumer engagement and decision-making (Frank et al., 2021; Hajli et al., 2022; Nguyen and Malik, 2022; Söderlund and Oikarinen, 2021; Tiberius, Gojowy and Dabić, 2022). While still years away from superintelligence (Bostrom, 2014), modern AI assistants are moving from human-in-the-loop operations, in which the AI relies on user input to perform tasks, such as instructions or permissions (de Bellis and Johar, 2020; Evanschitzky et al., 2015; Sestino et al., 2022), to human-out-of-the-loop operations, characterized by actions performed by the AI autonomously, without the need of human intervention (Fink et al., 2023; Sobolev, 2022). For example, Amazon's Alexa, the voice-controlled smart home AI assistant, has received the skill to act on its own ‘hunches,’ performing actions autonomously, such as switching off lights and radiators at home in the absence of the owners, calling emergency services when it detects unusual activities that the owners may not be capable of tackling themselves and reordering utilities when they are estimated to be running low (Campbell, 2021). While these actions may seem comforting, how would consumers respond to an autonomous AI assistant proactively ordering wine, flowers and condoms when it estimates their new relationship to have approached a more intimate stage – would they be pleasantly surprised or shocked to receive the delivery?

To examine people's general perceptions of high (vs. low) AI autonomy, we asked 190 Americans (age: M = 37.5, SD = 12.2; 50.5% female) how likely they would be to use an AI assistant for purchasing a new TV (1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely), given that the AI would either suggest they purchase the TV by notifying them when potential savings were highest or automatically purchase the TV when the potential savings were highest without notification. In both cases, participants were reminded that the purchase would be made with their own money. Despite representing a considerably less provocative scenario than that of the condoms, we found a remarkably strong and negative response towards AI autonomy, with a significantly lower preference for the AI high in autonomy (MHigh = 2.56, SD = 1.60) than for the AI low in autonomy (MLow = 4.75, SD = 1.58); t(189) = −15.71, p < 0.001, d = −1.14.1 This result sparks an intriguing question: Why are consumers less interested in high (vs. low)-autonomy AI, despite its potential to better assist them?

The AI adoption literature provides mixed answers to this question, with some studies mirroring the above results (Casidy et al., 2021; Huang and Qian, 2021) and others suggesting AI autonomy to drive consumer AI acceptance (Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey, 2018; Wen et al., 2022). This status quo leaves managers and institutional decision-makers at risk, as the uncertainty about the potential negative consequences of high-autonomy AI on consumer responses is yet to be systematically addressed (Botti, Iyengar and McGill, 2023; Frank et al., 2023).

In what follows, we investigate the influence of AI autonomy on consumers’ intentions to adopt AI assistant services in their daily lives. We propose that the shift in autonomy from consumers to AI should be closely linked to consumers’ personal sense of power. Across five experiments, with a total sample of almost 2000 consumers, we study consumer adoption of high (vs. low)-autonomy AI assistants across different online shopping settings. Our results document a strong negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions. Consumers’ personal sense of power acts as a psychological mechanism driving this effect, such that consumers who encounter a shopping situation involving high (vs. low) AI autonomy experience a state of powerlessness, which ultimately lowers their AI adoption intentions. Importantly, the influence of AI autonomy on consumers’ personal sense of power and AI adoption intentions is mitigated in shopping situations where popular options are quickly sold out, such as during Black Friday, highlighting scarcity as an important boundary condition. These results are robust across shopping settings, experimental designs and study paradigms, and apply even after controlling for a series of potential confounds. Additionally, the findings generalize across countries, representative samples and pre-registered study designs.

Our research contributes to the literature in three crucial ways. First, we expand the existing body of AI adoption research (Leone et al., 2021; Sestino et al., 2022) by empirically validating consumers’ fundamental need for autonomy (Botti, Iyengar and McGill, 2023; de Bellis and Johar, 2020; Wertenbroch et al., 2020) in modern shopping settings facilitated by AI agents.

Second, we document a novel psychological mechanism that helps explain consumers’ reluctance towards AI high in autonomy, supporting the notion that a transfer of autonomy from consumers to AI poses a challenge (Frank et al., 2023; Leung, Paolacci and Puntoni, 2018), as this shift induces powerlessness in consumers, thereby lowering their AI adoption intentions.

Third, we demonstrate a meaningful boundary condition, with scarcity moderating our focal effect. More precisely, we find that consumers’ aversion towards high (vs. low) AI autonomy is reduced when the limited availability of products is made salient. In other words, scarcity reduces consumers’ reluctance towards AI assistants high in autonomy, irrespective of whether behavioural intentions or consumer choice constitute the primary outcome.

From a practical perspective, our findings are relevant to managers and AI decision-makers in the service and retail sectors (Evanschitzky and Goergen, 2018; Ko et al., 2022), who are challenged to deliver optimal consumption experiences and utilize increasingly autonomous AI. In particular, the results offer valuable insights regarding strategies that may be successful in the future development, implementation and utilization of high-autonomy AI technologies. Proposed initiatives include establishing a common labelling for the autonomous capabilities of AI, as is done for vehicle driving automation systems (SAE International, 2021), to actively address the potential state of powerlessness consumers may face when transferring agency to highly autonomous AI assistants.

Theoretical background

Even before the advent of AI, researchers were interested in understanding the factors that influence consumer adoption and use of intelligent and even superintelligent systems (Bostrom, 2014). Since the dawn of AI-related research, scholars have studied a wide range of aspects related to consumers’ AI adoption (e.g. Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey, 2015; Longoni and Cian, 2020; Schmitt, 2020). Although such scholarly work has yielded profound insights, the rise of AI autonomy and the lack of research that has manipulated and quantified the consequences of said autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption have prompted scholars to call for more research on this topic (Frank et al., 2023). In the following sections, we integrate several streams of literature to provide plausible predictions of whether, why and under what circumstances AI autonomy should influence consumers’ AI adoption decisions. Rather than relying on a single theory, we combine frameworks centred on autonomy and consumer choice (Wertenbroch et al., 2020), with conceptualizations of personal sense of power (Magee and Galinsky, 2008) and scarcity (Hamilton et al., 2019), given the value of using such an integrative approach (Graham, 2013; Takeuchi et al., 2005). From a meta-theoretic perspective, we use the ‘explaining theory’ type (Sandberg and Alvesson, 2021), in which we explain a phenomenon through a set of logically related variables using relevance criteria focused on accuracy and testability, while specifying the causal impact, generality and boundary conditions of our proposed chain of events (Bacharach, 1989; Hambrick, 2007).

AI, autonomy and consumer choice

Scholars in the field of AI research differentiate between two primary directions: narrow AI, also known as weak AI, and strong AI, commonly referred to as general AI (Linde and Schweizer, 2019). Some also propose the existence of a third direction, known as superintelligent AI (Bostrom, 2014; Scott et al., 2022). Narrow AI, as defined by Linde and Schweizer (2019), refers to the ability of an AI agent to achieve specific goals within a limited set of environments. It is expected that narrow AI will outperform humans in these specific tasks. Examples of narrow AI include self-driving cars and popular virtual assistants like Siri, Alexa and Google's automated translation feature (Scott et al., 2022). Beyond this, AGI, or strong (general) AI, aims to encompass a unified system capable of comprehensive human-like intelligence across various cognitive domains such as language, perception, reasoning, creativity and planning (Scott et al., 2022).

AI systems also differ in their level of autonomy. In this research, AI autonomy is defined as ‘the ability of the AI technology to perform tasks derived from humans without specific human interventions’ (Hu et al., 2021, p. 2). As such, AI autonomy refers to the extent to which AI can perform actions and execute tasks without requiring human intervention, feedback or approval (Frank et al., 2023). A systematic review of the AI adoption literature, with a focus on autonomy aspects (Table 1), shows that prior studies fall short in capturing the unique shift in power dynamics that results from modern, highly autonomous AI systems. In fact, only a few studies have examined AI autonomy as an independent variable for explaining consumer choices to adopt (vs. not adopt) AI, including its advice and dependencies. Even fewer studies have experimentally manipulated AI autonomy. This makes managerial decision-making regarding AI autonomy a risky business, considering the lack of cause–effect relationships established.

| Study | Conceptualization of AI autonomy and related constructs | Sample* | Experimental† | AI autonomy as independent variable/manipulated | Representative‡ | Preregistration/open data | Moderation | Mediation | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tavitiyaman, Zhang and Tsang (2022) | Service automation: The delivery of predetermined tasks by automated machinery | N = 301 | ✓ |

|

|||||

| Voorveld and Araujo (2020) | Virtual assistants: Voice- or text-activated software agents that interpret requests by users and execute commands | N = 180 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|||

| Balakrishnan and Dwivedi (2021) | Automated chatbot: A computer program that conducts a conversation in natural language and sends a response based on business rules and data tuned by the organization | N = 410 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Casidy et al. (2021) | Autonomous vehicles: Higher-level automated driving systems that control all dynamic aspects of the driving task under all roadway and environmental conditions |

N = 294 N = 288 N = 575 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|||

| Fernandes and Oliveira (2021) | AI-based digital voice assistants: Virtual conversational agents that recognize and understand voice-based user requests and communicate using natural language to accomplish a wide variety of tasks | N = 238 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Flavián et al. (2022) | Robo-advisor agents: Agents that automate or assist in managing investments by replacing human advisory services and/or the customer's own management | N = 404 | (✓) | ✓ |

|

||||

| Frank et al. (2021) | AI product autonomy: Products that autonomously perceive their environment and take autonomous actions to achieve their objectives without requiring consumer intervention or feedback | N = 1388 |

(✓) Within-subjects design |

✓ |

(✓) Urban sample |

✓ |

|

||

| Huang and Qian (2021) | Autonomous vehicles: Vehicles powered by AI technology that are highly or fully automated and require limited or no human intervention | N = 849 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Ribeiro, Gursoy and Chi (2022) | Autonomous vehicles: Vehicles that can drive without human intervention | N = 362 | ✓ |

|

|||||

| Shareef et al. (2021) | Autonomous system: Any integrated and interconnected process or product that can act independently, making appropriate contextual decisions within a changing environment and without any human intervention | N = 112 | ✓ |

|

|||||

| Alfalhi (2022) | Intelligent automation: Bringing together automation and AI to facilitate value-adding change through new technology, which permits autonomous interaction with people and tasks | N = 330 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Ali, Swiety and Mansour (2022) | Robotic process automation: Software that imitates rules based on digital tasks performed by humans | N = 179 |

|

||||||

| Meyer-Waarden and Cloarec (2022) | AI-powered autonomous vehicles: Vehicles in which human drivers are never required to take control to safely operate the vehicle, and where the execution is performed by an AI-based machine agent of a function that was previously carried out by humans | N = 207 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Osburg et al. (2022) | Autonomous vehicle service: Modes of autonomous transport, which make substantial use of artificial intelligence, operating services for public, private or goods transportation, but excluding privately owned AVs for personal use |

N = 27,565 N = 300 |

✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Piehlmaier (2022) | Robo-advisors: Algorithmic wealth management tools that rely on AI to efficiently allocate investments using exchange-traded funds and index funds due to their simple cost structure and passive approach to portfolio management | N = 2000 |

(✓) Investor sample |

✓ |

|

||||

| Sestino et al. (2022) | Product intelligence: The extent to which consumers perceive a product as an intelligent entity that is able to behave autonomously, learn and interact as a human being | N = 343 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|||

| Sharma et al. (2022) | Autonomous decision-making process (in the context of retailing): A system that can perform shopping processes delegated by customers, such as decisions and purchases | N = 454 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| Song and Kim (2022) | Retail service robot: Emerging robotic technology that employs AI to provide automated in-store customer service | N = 1424 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| von Walter, Kremmel and Jäger (2022) | Robo-advisors: Investment strategies without human intervention |

N = 454 N = 73 N = 227 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|||

| Wen et al. (2022) | AI autonomy: The extent to which AI can make autonomous decisions and execute tasks correctly without requiring human feedback | N = 528 | ✓ |

|

|||||

| Aw et al. (2023) | Perceived autonomy: The extent to which a robot requires human intervention and support to function | N = 375 | ✓ |

- Perceived anthropomorphism (human-like attributes) and perceived autonomy positively influence consumers’ perception of justice regarding robo-advisory services. - Perceived justice has a negative impact on consumers’ privacy concerns and perceived intrusiveness associated with robo-advisors. - Privacy concerns and perceived intrusiveness positively influence consumers’ resistance to adopting robo-advisory services |

|||||

| Chua, Pal and Banerjee (2023) | Automation bias: When users readily buy into computer recommendations instead of relying on their own judgement | N = 368 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|||

| Dorotic, Stagno and Warlop (2023) | AI autonomy: The extent to which technology operates without human control or intervention |

N = 4523 N = 790 N = 367 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||

| Fink et al. (2023) | Fully autonomous vehicles (FAVs): Vehicles where humans are riding with an autonomous AI driver | N = 187 |

|

||||||

| Qian et al. (2023) | Autonomous vehicles (AVs): Equipped with sensors and connecting devices, AVs can automatically detect road infrastructure, pedestrians and nearby vehicles | N = 880 | ✓ | ✓ |

|

||||

| The present research | AI autonomy: The extent to which AI can make decisions and execute tasks without requiring human intervention, feedback or approval |

N = 710 N = 392 N = 241 N = 417 N = 221 |

✓ |

✓ (High vs. Low) |

✓ Consumer sample |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

- Note: *Denotes sample sizes in main studies, excluding pretests and pilot studies. †Parentheses denote studies that were not experimental between-subjects. ‡Parentheses denote studies that were close to but not fully representative of the target population. The literature presented originates from a Scopus title/abstract/keyword search on peer-reviewed articles published in the domains of ‘Psychology’ and ‘Business, Management and Accounting’ in English (as of 23 October 2023). We restricted the articles to those that matched the following text-search criteria: (‘artificial intelligence’ OR ‘AI’) AND (service OR retail OR consumer OR customer OR management OR market* OR shop*) AND (adopt*) AND (auto*). This search resulted in a total of 178 articles that were screened for suitability. Articles based on quantitative empirical evidence with a focus on AI autonomy in consumer choice and shopping settings were selected for inclusion, resulting in a final sample of 25 empirical articles (plus the current article) as summarized above.

- H1: Online retail shopping involving high (vs. low) AI autonomy will have a negative impact on consumers’ AI adoption intentions.

Personal sense of power

The act of adopting high-autonomy AI entails a shift in decision power from consumers to AI agents. This transfer of decision power to AI systems represents a fundamental alteration in the power dynamics between consumers and technology (Faraji-Rad, Melumad and Johar, 2017). Hence, we argue that understanding the ramifications of this shift in power is key for grasping the negative impact of high levels of AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption. In this context, the aspect of empowerment emerges as a critical component within consumer agency, encompassing the capacity to make autonomous choices and exert influence over one's own decision-making processes (Denegri-Knott, Zwick and Schroeder, 2006). By acknowledging the impact of AI autonomy on consumers’ sense of agency, researchers can gain deeper insights into the factors influencing consumer adoption and the potential barriers arising from the perceived loss of power.

- H2: The negative impact of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions will be mediated by consumers’ personal sense of power, with consumers who encounter online retail shopping involving high (vs. low)-autonomy AI being more (vs. less) prone to experience a state of powerlessness, thereby decreasing their AI adoption intentions.

Scarcity

Consumers’ sense of power interacts with various situational factors (Fan, Rucker and Jiang, 2022; Magee and Galinsky, 2008). This implies that certain contexts, such as a consumer recalling an instance when someone else had power over him- or herself, can induce feelings of powerlessness. Conversely, reflecting upon a situation where the consumer exerted power over another individual can trigger the reverse (Galinsky, Gruenfeld and Magee, 2003). One situational factor that can influence this dynamic is scarcity.

Scarcity is broadly conceptualized as a state of shortage compelling individuals to engage in specific behaviours (Elbæk et al., 2023; Hamilton et al., 2019; Suri et al., 2007). In consumers’ everyday lives, such a shortage is often related to time and product scarcity. Consumers also frequently face scarcity-based messages and events (limited edition, last chance to buy, Black Friday; Abendroth and Diehl, 2006; Folwarczny et al., 2022; Tang, Li and Su, 2022).

- H3: Consumers’ intentions to adopt high (vs. low)-autonomy AI will be moderated by scarcity, such that the negative effect of high (vs. low)-autonomy AI on AI adoption is attenuated when the limited availability of products is made salient.

- H4: The impact of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ adoption intentions will be mediated by their personal sense of power and moderated by scarcity. In regular shopping settings, consumers who encounter a high (vs. low)-autonomy AI will be more (vs. less) prone to experience a state of powerlessness, thereby decreasing their AI adoption intentions. In shopping settings where the limited availability of products is made salient, by contrast, consumers’ personal sense of power will no longer mediate the link between AI autonomy and adoption intentions.

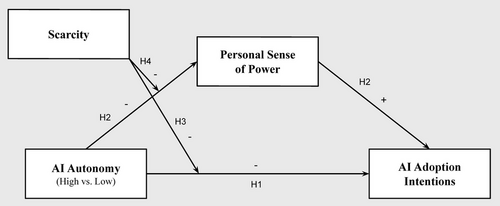

We test these hypotheses in a series of experiments across diverse samples, shopping settings and situational circumstances. Figure 1 depicts our conceptual model.

Overview of studies

Table 2 provides an overview of the empirical work of the current research. Studies 1A and B serve to establish the main effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ intentions to adopt AI. Study 2 provides evidence for the psychological mechanism driving this effect through consumers’ personal sense of power. Studies 3 and 4 document scarcity as an important boundary condition, with consumers being more inclined to choose (Study 3) and adopt (Study 4) high (vs. low)-autonomy AI under conditions of scarcity, with the negative effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ personal sense of power attenuated in such settings (Study 4). All reported studies were experiments and involved real consumers from the United States and the United Kingdom. The manipulations were effective and deemed realistic, as confirmed by our manipulation and realism checks available in the Online Appendix.

| Study | Method | Sample | Design | Focus | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | Pre-registered experiment | N = 710; representative | 2 AI autonomy; between-subjects | Main effect | AI autonomy exerts a robust and negative effect on consumers’ AI adoption intentions. |

| 1B | Experiment | N = 392 | 2 AI autonomy; between-subjects | Main effect | The negative effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions occurs even after controlling for consumers’ personality traits, technology readiness, purchase decision involvement, AI and product category knowledge, and AI experience. |

| 2 | Experiment | N = 241 | 2 AI autonomy; between-subjects | Mediation | Consumers’ personal sense of power mediates the negative effect of AI autonomy on their AI adoption intentions. |

| 3 | Choice experiment | N = 417 | 2 AI autonomy × Scarcity; within-subjects | Moderation | Scarcity attenuates the negative influence of high AI autonomy in a consumer choice context. |

| 4 | Experiment | N = 221 | 2 AI autonomy × 2 scarcity; between-subjects | Moderated mediation | Scarcity attenuates the negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions, with personal sense of power no longer mediating the autonomy–adoption intentions link under such circumstances. |

Study 1A: Pre-registered test of the main effect

Study 1A aims to establish evidence of the hypothesized negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions using a pre-registered study based on representative samples of US and UK consumers (for details, see https://osf.io/54hkj/).

Participants, design and procedure

Responses from representative samples (N = 710) in terms of age, gender and ethnicity were collected from the online panel Prolific. Participants were from the United States (n = 354; age: M = 44.4, SD = 15.9; 50.8% female) and the United Kingdom (n = 356; age: M = 44.8, SD = 15.0; 52.5% female) and took part in the study voluntarily after providing written consent in exchange for monetary compensation.

Participants were asked to consider allowing an AI shopping assistant to help them purchase a new digital camera. The AI high in autonomy would automatically purchase the camera when it determined that the potential savings were the highest, whereas the AI low in autonomy would merely notify them to make the purchase (between-subjects).

In response to the respective shopping scenario, participants rated their intention to use the AI shopping assistant (‘How likely are you to use the artificial intelligence assistant for purchasing the digital camera?’; 1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely), followed by a manipulation check, as described in our pre-registration.

Results

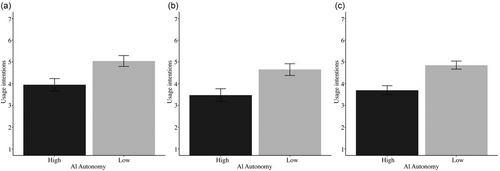

As shown in Figure 2, the results provide support for H1, irrespective of whether the US and UK samples were analysed separately or together. Three Bonferroni-corrected independent sample t-tests revealed that participants were significantly less inclined to use the high (vs. low)-autonomy AI in each of these cases: (a) US sample (MHigh = 3.94, SD = 1.93 vs. MLow = 5.04, SD = 1.72; t(352) = −5.65, p < 0.001; d = −0.60); (b) UK sample (MHigh = 3.48, SD = 2.04 vs. MLow = 4.65, SD = 1.78; t(354) = −5.74, p < 0.001; d = −0.61); and (c) total sample (MHigh = 3.70, SD = 2.00 vs. MLow = 4.85, SD = 1.76; t(708) = −8.14, p < 0.001; d = −0.61).2

Discussion

Study 1A provides pre-registered evidence for the notion that an AI assistant with high autonomy leads to significantly lower usage intentions than an AI assistant with low autonomy in the context of online shopping. This effect holds in a high-powered study with representative samples from the United States and the United Kingdom, and represents a large effect size by conventional standards (Funder and Ozer, 2019).

Study 1B: Replication of main effect

To further test the generalizability of the negative main effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions (H1), we conducted a follow-up experiment based on the same AI assistant shopping scenario in Study 1A. This time, we controlled for a number of factors that could potentially have influenced our initial results, including consumers’ personality traits, technology readiness, purchase-decision involvement, subjective and objective knowledge about AI and self-reported experience with AI. We included these additional factors to rule out the possibility that our results could have emerged due to any of these confounds rather than, as we expected, AI autonomy.

Participants, design and procedure

Responses from a US consumer sample (N = 392; age: M = 46.6, SD = 14.4; 49.5% female) were collected from the online panel Prolific. Participants were exposed to the same shopping scenario introduced in Study 1A, and responded to the same intention-to-use item. Additionally, this study included a series of validated scales on consumers’ purchase-decision involvement (e.g. ‘How important would it be to you to make a right choice of an artificial intelligence shopping assistant?’; 1 = not at all important to 7 = extremely important; Cronbach's α = 0.78; Mittal, 1995), technology readiness (e.g. ‘I keep up with the latest technological developments in my areas of interest’; 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.83; Parasuraman, 2000) and Big Five personality dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality and open-mindedness) using the 15-item BFI-2-XS inventory (αE = 0.60, αA = 0.62, αC = 0.76, αN = 0.78, αO-M = 0.65; Soto and John, 2017). Moreover, participants answered questions about their subjective knowledge about the product category (‘How knowledgeable are you about digital cameras?’; 1 = not at all to 7 = a great deal), subjective knowledge about AI (‘How knowledgeable are you about artificial intelligence in general?’; 1 = not at all to 7 = a great deal), personal experience with AI assistants (‘How often do you use artificial intelligence assistants (e.g. Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant, ChatGPT, etc.)?’; 1 = never to 7 = all the time) and responded to six true–false statements as a measure of their objective knowledge about AI (e.g. ‘Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the simulation of human intelligence in machines’, ‘AI systems always improve their performance over time without human intervention’). The study ended with a manipulation check (‘Who made the final decision on purchasing the digital camera?’; 1 = myself to 7 = the artificial intelligence assistant) and a realism check (‘To me, the described artificial intelligence assistant seems…’; 1 = unrealistic to 7 = realistic).

Results

To examine potential confounding effects related to the impact of AI autonomy on consumers' AI adoption intentions, we performed a linear regression analysis (PROCESS Model 0; Hayes, 2018). AI autonomy (high = 1, low = 0) was the predictor, AI adoption intention was the outcome variable and all control variables (purchase-decision involvement, technology readiness, Big Five personality traits, subjective and objective knowledge about AI, subjective knowledge about the product category and personal experience with AI assistants) acted as covariates. The continuous variables were z-scored before analysis to allow for standardized coefficients (Gasiorowska, Folwarczny and Otterbring, 2022).

The fitted model successfully accounted for 27.4% of the variation in participants’ AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the R2 value. Supporting H1, this model showed a significant and strong negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on participants’ AI adoption intentions (b = −1.32, SE = 0.17, p < 0.001). Besides AI autonomy, only two of the other variables yielded significant effects: participants’ personal experience with AI assistants (b = 0.62, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001) and their agreeableness levels (b = 0.24, SE = 0.10, p = 0.016), implying that higher values on these variables were linked to greater AI adoption intentions. Follow-up moderation analyses revealed that neither personal experience with AI assistants nor agreeableness moderated the main effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on participants’ AI adoption intentions (ps > 0.40 in both cases), underscoring the robustness and replicability of our main finding.

Discussion

Study 1B confirms a strong and negative main effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions even after accounting for several theoretically relevant control variables, thus attesting to the generality of our focal effect and ruling out several alternative explanations for our results.3

Study 2: Mediation through personal sense of power

Study 2 investigates the extent to which consumers’ personal sense of power explains the negative relationship between AI autonomy and consumers’ AI adoption intentions (H2). We predict that consumers are less inclined to adopt AI high (vs. low) in autonomy to do their shopping because the shift in autonomy away from consumers and towards the AI induces feelings of powerlessness. Personal sense of power has been linked to self-esteem and negative affect (Talaifar et al., 2021; Wang, 2020; Wojciszke and Struzynska-Kujalowicz, 2007), with low self-esteem and negative affect also yielding effects on consumer responses similar to those occurring for the powerless (Rucker and Galinsky, 2008; Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010). Therefore, to provide more substantive evidence for the uniqueness of our proposed mechanism and rule out these two alternative accounts, we also collected data on participants’ self-esteem and affect.

Participants, design and procedure

Respondents (N = 241; age: M = 37.6, SD = 11.8; 56.0% female), recruited from Amazon's MTurk panel, were randomly assigned to an AI autonomy shopping scenario using the same single-factor between-subjects design and shopping scenarios introduced in Study 1A. In response to their assigned scenario, participants indicated their usage intention (‘How likely are you to use the artificial intelligence assistant for purchasing…?’), trial intention (‘How likely are you to try the artificial intelligence assistant…’) and subscription intention (‘How likely are you to subscribe to the artificial intelligence assistant…’) on seven-point scales (1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely) regarding the respective AI shopping assistant that was framed as either being high or low in autonomy. As these measures of intention were highly correlated (α = 0.87), they were subsequently averaged into a composite index of AI adoption intentions.

Next, participants completed an adapted version of the eight-item Personal Sense of Power Scale (Anderson, John and Keltner, 2012) by indicating their agreement on eight statements (e.g. ‘I can get the AI to listen to what I say’, ‘I think I have a great deal of power’) using a seven-point scale (1 = disagree strongly to 7 = agree strongly; α = 0.90). To increase the internal validity of the study and hence control for the potentially confounding factors of self-esteem and affective influences, participants also replied to the well-validated single-item self-esteem scale (Robins, Hendin and Trzesniewski, 2001) by indicating their agreement with the statement ‘I have high self-esteem’ (1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly), after which they replied to the ten-item International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) Short Form scale (1 = never to 5 = always; αPA = 0.78, αNA = 0.86; Thompson, 2007).4 Finally, they replied to the same manipulation and realism checks as those used in Study 1B.

Results

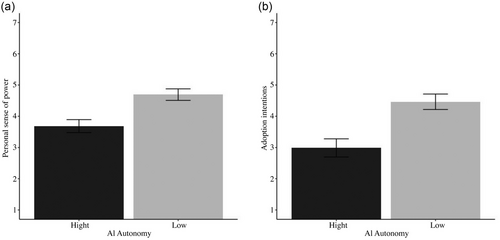

To examine whether participants’ personal sense of power, shown in Figure 3A, mediates the effect of AI autonomy on participants’ AI adoption intentions, shown in Figure 3B, we performed a mediation analysis (PROCESS Model 4; Hayes, 2018) with AI autonomy (high = 1, low = 0) as the predictor, personal sense of power as the mediator and the composite index for adoption intentions as the outcome variable. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using 5000 bootstrap samples.

The model explained roughly 33% of the variance in consumers’ AI adoption intentions (R2 = 0.33), with the results revealing a significant and negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy (b = −1.48, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001). Personal sense of power, in contrast, had a significant and positive effect on AI adoption intentions (b = 0.67, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001). However, when AI adoption intentions were regressed on both AI autonomy and personal sense of power, the effect of AI autonomy on adoption intentions was clearly reduced (b = −0.92, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001). The bootstrapped indirect effect of AI autonomy through personal sense of power was significantly different from zero (95% CI: [−0.81, −0.35]). Thus, in line with H2, high (vs. low) AI autonomy resulted in significantly lower adoption intentions as the more (vs. less) autonomous AI shopping assistant decreased participants’ personal sense of power.5 An additional meditation analysis that controlled for participants’ self-esteem, positive and negative affect, age and gender showed no consistent influence of any of these variables on AI adoption intentions, nor did the inclusion of these variables change the nature or significance of our results.

Discussion

Study 2 provides evidence that AI high in autonomy induces a state of powerlessness in consumers, whereas AI low in autonomy induces a state of powerfulness. Importantly, we find support for the mechanism that explains the negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ adoption intentions. More precisely, our results show that the shift in autonomy associated with a more autonomous AI induces a state of powerlessness in consumers, driving their AI adoption intentions in an aversive way. Further, we rule out a series of alternative accounts, such as affective influences or effects emerging due to self-esteem. However, we have yet to demonstrate a relevant boundary condition for our focal effect; a topic we address in Study 3.

Study 3: Moderation through scarcity

In Study 3, we test the degree to which the presence (vs. absence) of scarcity cues can attenuate the negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions (H3). According to our theorizing, consumers who face a situation characterized by scarcity, such as shopping during a narrow time window when products are sold out rapidly, should be less reluctant to adopt an AI high (vs. low) in autonomy, despite a shift in autonomy towards the AI. Therefore, we posit that the general negative effect of high-autonomy AI should be reduced when consumers use such an AI in settings characterized by scarcity, because the higher autonomy of the AI should not be perceived as a loss of autonomy to the same extent under such conditions (Lynn, 1992). To enhance realism and boost the ecological validity of our work (Loebnitz et al., 2022; Morales, Amir and Lee, 2017; Otterbring, 2021), we test this thesis in a setting wherein participants make an active choice between a high- and low-autonomy AI assistant.

Participants, design and procedure

Responses from US consumers (N = 417; age: M = 43.0, SD = 13.4; 51.3% female) were collected from the online panel Prolific. Participants were exposed to two scenarios (within-subjects) in which they were asked to imagine shopping for a new vacuum cleaner and, for each scenario, were offered a high- or a low-autonomy AI assistant to help them.

In the scarcity condition, participants were told that the availability of the target product (i.e. the vacuum cleaner) would be severely limited in the near future. The control condition did not emphasize that product availability constituted a concern, with desirable options instead described as having excellent availability in the near future.6

After having made their AI shopping assistant choice for each scenario (scarcity vs. control), participants indicated their responses on one manipulation check per scenario, in which they rated the availability of desirable options of vacuum cleaners over the next couple of days on a scale from 1 = severely limited to 7 = completely unrestricted. Finally, they replied to the same realism check used in the former studies.

Results

Consistent with H3, a 2 (condition: scarcity vs. control) × 2 (consumer choice: high vs. low AI autonomy) Pearson's chi-square analysis revealed that the proportion of participants choosing the shopping assistant characterized by high (vs. low) AI autonomy was significantly greater in the scarcity condition (21.1%) than in the control condition (15.6%; χ2(1) = 4.23, p = 0.040).

Discussion

The results of Study 3 demonstrate that scarcity shifts consumer choice more towards high-autonomy AI relative to the shopping settings used across all former studies that lacked explicit cues to scarcity. Thus, although consumers are generally reluctant to prefer and choose high-autonomy AI, even under conditions of scarcity, this aversion is reduced when products are described as only having limited availability, irrespective of whether such product availability aspects are made salient in isolation or are combined with objective manipulations of time constraints.

Study 4: Testing the entire moderated mediation model

In Study 4, we test whether the general negative effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions is mediated by their personal sense of power and moderated by scarcity, with the mediation through personal power only occurring under regular shopping settings but not those characterized by scarcity (H4). According to our theorizing, and as observed in Study 3, consumers who face a shopping situation where the scarcity concept is made salient should be less reluctant to adopt an AI high in autonomy, despite a shift in autonomy from themselves to the AI. We posit that this occurs because the higher autonomy of the AI, unlike regular shopping settings, should no longer be perceived as a personal loss of power under conditions of scarcity. To rule out alternative accounts, we capture participants’ desire for unique consumer goods (Lynn, 1992). Prior research has discussed powerlessness in terms of consumers being more prone to prefer exclusive and unique products (Mandel et al., 2017; Rucker and Galinsky, 2008; Zou et al., 2014). Although the power construct is distinct from various facets of uniqueness (Folwarczny et al., 2021), a critic might argue that our mechanism is not necessarily restricted to a sense of powerlessness. Study 4 sought to exclude this possibility and thus add further support to our precise psychological mechanism (personal sense of power), while simultaneously demonstrating the robustness and replicability of our moderator (scarcity).

Participants, design and procedure

US consumers (N = 221; age: M = 38.8, SD = 11.3; 54.8% female), recruited from Amazon's Mechanical Turk panel, were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions in a 2 (AI autonomy: high, low) × 2 (scarcity: yes, no) between-subjects design. They were instructed to imagine being in the process of purchasing a digital camera, either during Black Friday ‘with good options being sold out very quickly’ or, alternatively, in the next couple of months ‘with good options available at all times’ (without any reference to Black Friday). As before, they were offered either an AI shopping assistant high in autonomy, or alternatively, an AI assistant low in autonomy.

After reading their assigned scenario, participants replied to the same primary measures formerly used to capture our mediator and dependent variable, with the index variables of personal sense of power (α = 0.87) and adoption intentions (α = 0.83) found to be reliable. As a manipulation check of scarcity, participants rated the statement ‘In the described scenario, the availability of the digital camera was…’ (1 = very low to 7 = very high). Further, we included the eight-item Desire for Unique Consumer Products scale (adapted from Lynn and Harris, 1997) with items such as ‘I am very attracted to rare objects’ and ‘I am more likely to buy a product if it is scarce’ (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), and combined the responses into a composite index (α = 0.86) to control for the potential confound of this construct in the analyses.

Results

To examine our focal hypothesis (H4), whereby the impact of AI autonomy on consumers’ adoption intentions should be mediated through their personal sense of power under regular shopping conditions, but not in settings characterized by scarcity, we performed a moderated mediation analysis with participants’ personal sense of power (continuous) as mediator and scarcity (yes = 1, no = 0) as moderator (PROCESS Model 8; Hayes, 20182018). AI autonomy (high = 1, low = 0) was the predictor, and adoption intentions (continuous) acted as the outcome variable. We used 5000 bootstrap samples to compute the 95% CIs.

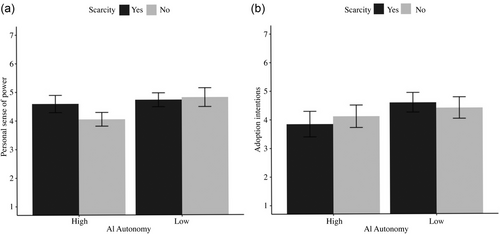

In support of H4, the conditional indirect effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy through personal sense of power on adoption intentions was not significant under conditions of scarcity (b = −0.06, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: [−0.21, 0.11]) but was significant and negative under regular circumstances (b = −0.31, SE = 0.11, 95% CI: [−0.54, −0.12]), thereby replicating the pattern of our earlier studies. Supporting this finding, the index of moderated mediation was significant (b = 0.26, SE = 0.14, 95% CI: [0.02, 0.56]), confirming that the indirect effect of AI autonomy on adoption intentions through consumers’ personal sense of power was indeed moderated by scarcity. Additional moderated mediation analyses controlling for participants’ desire for unique consumer products, besides age and gender, showed no consistent influence of these factors on our focal variables, and did not change the nature or significance of our results. The ratings for consumers’ personal sense of power and adoption intentions by AI autonomy × scarcity conditions are depicted in Figure 4.

Discussion

The results from Study 4 conceptually replicate the mediating role of consumers’ personal sense of power in the (no-scarcity) control condition, such that consumers’ adoption intentions are consistently lower for high relative to low AI autonomy due to a sense of powerlessness in such regular shopping settings. Importantly, the negative influence of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ perceived personal sense of power levels and adoption intentions was neutralized when the shopping setting was characterized by scarcity, thus highlighting an important boundary condition of the previously demonstrated aversive aspects associated with high AI autonomy.

General discussion

The present research investigates consumers’ intentions to adopt AI as a function of the AI's autonomy. The results reveal a robust, negative influence of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on AI adoption in the context of online shopping, as long as the shopping situation is not characterized by scarcity. We also find that this effect is driven by a state of powerlessness linked to consumers’ transfer of agency from themselves towards the more autonomous AI. These findings challenge the notion that more autonomous AI technologies will be superior in generating favourable consumer responses. If anything, our studies reveal the reverse – as long as the consumption context does not counter the aversive aspects associated with AI autonomy, as demonstrated in the presence of scarcity.

Theoretical contribution

From a theoretical perspective, our work makes three key contributions. First, the current studies contribute to the growing stream of research on consumer adoption of AI technologies (Frank et al., 2023; Hajli et al., 2022; Leone et al., 2021; Sestino et al., 2022) by empirically validating consumers’ need for autonomy as a central construct in consumption contexts that feature increasingly autonomous technology. Contrary to prevailing assumptions and anecdotal evidence (Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey, 2018; Wen et al., 2022), we find that AI autonomy does not generally add value for customers, although shopping settings characterized by scarcity seem to attenuate the aversion towards high (vs. low) AI autonomy. This finding underscores the complex interplay of consumer agency and AI autonomy (Dorotic, Stagno and Warlop, 2023; Mourali and Nagpal, 2013; Wertenbroch et al., 2020), and also adds to the ongoing discussion about automation anxiety in other AI adoption contexts (Kelan, 2023).

Second, the results show that the level of autonomy of AI shopping assistants has downstream effects on consumers’ personal sense of power, substantiating earlier speculations that high AI autonomy might be less preferred by consumers (Carmon et al., 2019; see also Schweitzer and Van den Hende, 2016). Our extensive testing of the psychological mechanism driving consumers’ adoption intentions of high (vs. low) AI autonomy through their personal sense of power thus contributes to earlier findings, while ruling out alternative accounts for AI reluctance, such as those linked to different consumption contexts (Longoni and Cian, 2020), consumers’ self-esteem (Wang, 2020) and their need for uniqueness (Longoni, Bonezzi and Morewedge, 2019), as well as a wide array of other individual difference factors, including the Big Five personality traits (Cerekovic, Aran and Gatica-Perez, 2017), consumers’ technology readiness (Flavián et al., 2022) and their purchase-decision involvement (Sihi, 2018), as well as subjective and objective knowledge about AI (Cadario, Longoni and Morewedge, 2021) and prior experiences with AI (Frank et al., 2023).

Third, by documenting the boundary condition of scarcity, the present research offers a more nuanced understanding of whether, why and when consumers are particularly prone to rely on more autonomous AI assistance. Specifically, our results document that scarcity neutralizes the negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions, with scarcity motivating a relative shift towards high-autonomy AI alternatives. As such, our studies paint a more complete picture regarding under what circumstances customers might be willing to forego their own autonomy (Botti, Iyengar and McGill, 2023).

Practical implications

Our findings suggest that marketers should implement strategies that help overcome, or at least reduce, consumers’ perceived power loss to counter their strong reluctance towards highly autonomous AI assistants, which will be increasingly prevalent in the future retailing landscape. These strategies could rely on implementing mechanisms that retain some level of control over the AI system (de Bellis and Johar, 2020; Whang et al., 2021) or allow consumers to receive more nuanced explanations for the rationale behind autonomous actions (Zhang et al., 2022). In the example used at the beginning of this paper, Amazon Alexa proactively informs users why and when it has taken action though ‘hunches,’ and gives users the option to object to future actions of that sort. Similarly, to preserve autonomy of one's own choices, our findings suggest that it might be better if the AI only notifies consumers that a given action can be performed. The AI should then wait for consumer approval before proceeding with the action, abandoning the concept of AI making these decisions proactively (Otterbring et al., 2023). Another approach to tackle the powerlessness induced by high AI autonomy might be to implement self-affirmative actions into the routines of AI assistants, given that self-affirmation can offset powerlessness with potential effects on subsequent consumption responses (Moeini-Jazani, Albalooshi and Seljeseth, 2019; Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010). An example of such an approach would be to program AI systems to regularly communicate their goals and offer assistance when they sense that customers likely encounter problems, have inquiries or face insecurities.

Another implication that emerges from this research is that AI adoption may be more successful in shopping settings where autonomous AI assistants are less likely to induce a sense of powerlessness in consumers. Our results show that the negative effect of high-autonomy AI shopping assistants is less prevalent in situations that convey cues to scarcity. This finding implies that consumers are more willing to transfer autonomy to AI assistants in certain contexts as a means to avoid sole responsibility over outcomes resulting from their decisions (Botti, Orfali and Iyengar, 2009). Thus, AI autonomy does not necessarily harm consumer adoption across all consumption contexts, as long as marketers can leverage appropriate situations (e.g. promotional activities during a predefined and narrow time window) or marketing messages (e.g. last chance to buy, limited edition, final offer), such that consumers’ personal sense of power remains, without the experience that autonomy is lost in the purchasing process. However, these tactics should be used with caution, as repeated exposure to scarcity appeals when promoting AI high in autonomy can backfire and lead to reputational costs for companies if claims related to the limited availability of certain products – in time, space or quantity – are based on false information and communicated in an insincere way (cf. Otterbring and Folwarczny, 2024).

Our research complements the endeavours of law- and policymakers in various regions, such as the European Union, United States and Canada, who are working to establish regulations for AI system design. These regulations are driven by concerns about the potential adverse societal implications and ethical dilemmas associated with AI (Tiberius, Gojowy and Dabić, 2022) and other impactful modern technologies adopted by consumers (Nyhus et al., 2023). Our findings indicate that implementing a labelling scheme for the different levels of AI autonomy could be beneficial, as it might help consumers understand if, when and how AI assistants are going to make critical actions and decisions on their behalf. These labels may relate to actions (‘this purchase was performed by an AI’), communications (‘this message was sent by an AI’) and representations (‘this system is automated and operated by an AI’), allowing for traceability and accountability of AI. Importantly, the use of a labelling scheme would empower consumers to deliberately choose in favour of high-autonomy AI, whenever the transfer of agency is deemed superior.

Limitations and future research

While we find a robust negative effect of high (vs. low) AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions, with no signs of moderation through the individual difference factors included, we acknowledge that other individual differences not addressed herein could still moderate our obtained results. Similarly, despite the fact that consumers’ prior experiences with AI did not moderate our focal effect, this finding does not necessarily generalize after repeated exposure to, and experiences with, highly autonomous AI. That is, we expect consumer experiences with AI to develop over time, likely leading to greater acceptance of high AI autonomy. Hence, future research may benefit from studying consumer responses towards AI autonomy longitudinally, or over a longer time span, to capture how current and future AI offerings are shaping, changing and developing consumers’ AI adoption intentions.

Scarcity in promotional sales settings almost always entails some aspects of both time and product scarcity, given that the limited availability of products would naturally result in options being sold out rapidly. Nevertheless, in an attempt to separate these sources of scarcity, we tested for potential differences in consumers’ choice between high (vs. low)-autonomy AI assistants, depending on whether our scarcity manipulation did or did not include an objective manipulation of time constraints (Study 3). We found no difference in consumer choice across these scarcity settings, although consumers in the combined scarcity condition were significantly more inclined to choose the high-autonomy AI assistant compared to those in the control condition. This finding tentatively suggests that our focal effect may emerge, even without objective manipulations of time constraints. However, we maintain that it is challenging to isolate the effects of time and product scarcity in experimental settings, meaning that these tentative conclusions need to be validated in future studies.

This research, while novel and managerially relevant, is restricted to weak AI. As indicated in the introduction to this paper, the development of more intelligent AI is around the corner (Linde and Schweizer, 2019). While existing AI systems may not (yet) have reached the stage of superintelligence (Bostrom, 2014), AI development is happening rapidly (Scott et al., 2022), implying that future AI will likely continue to evolve capabilities that challenge managers’ current understanding of consumer responses. Intertwined with autonomy, such capabilities may also be linked to the amount and type of information AI gathers about consumers by tracking their preferences, habits and behaviours to reliably make suggestions or execute certain actions. Tracking of this type may be perceived as an erosion of privacy (Baum et al., 2023). Thus, further research is needed to examine the impeding factors that might slow down not only consumers’ current adoption rates of increasingly autonomous AI, but also their future adoption rates of strong AI.

Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the influence of AI autonomy on consumers’ intentions to adopt AI assistants in online shopping settings. We found that high (vs. low) AI autonomy can lead to a sense of powerlessness in consumers, which in turn lowers their AI adoption intentions. However, this effect is mitigated in situations where popular options are less available or quickly sold out. Our findings have implications for both theory and practice, as they empirically validate consumers’ fundamental need for autonomy in AI-related consumption contexts. Accordingly, managers should carefully consider the level of AI autonomy and the context in which it will be used when developing and implementing AI-powered technologies. Together, this research highlights the importance for managers, policymakers and researchers to closely focus on the shift in power dynamics between consumers and increasingly autonomous intelligent machines when seeking to understand consumers’ current and future adoption rates of AI assistants.

Transparency statement

In conducting and reporting this research, we have adhered to all APA ethical guidelines as well as the ethical guidelines of Denmark. The results have not been previously published, are reported honestly and the authorship accurately reflects each individual's contributions. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Aarhus University (No. 2021-53). The first author managed the collection of data for all studies using the consumer panels from Prolific (Studies 1A and B, 3 and A1) and Amazon's Mechanical Turk (Studies 2 and 4) in the spring and summer of 2021 and spring of 2023. Participants were unique to each study and did not participate in more than one study. The data were jointly analysed, reported and discussed by both authors. The anonymised data are stored in a public project directory on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/undmp/.

Biographies

Darius-Aurel Frank is an Assistant Professor of Marketing in the Department of Management, Aarhus University (Denmark). His research focuses on life with technology in the future, with an emphasis on exploring the dynamic relationship between marketing, innovation and sustainability. His work has appeared in esteemed journals across different fields including Nature Human Behavior, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, Information Technology & People and Psychology & Marketing.

Tobias Otterbring is a Professor of Marketing in the Department of Management, University of Agder (Norway) and a member of the Young Academy of Norway. His research focuses on how the real, imagined or implied presence of others influences consumers’ cognitions, emotions and actual purchase or choice behaviours. His work has appeared in journals such as Nature Human Behaviour, Nature Communications and PNAS, as well as in top-tier publications in marketing, management and psychology, including Journal of Marketing Research, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, British Journal of Management, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology and Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.

References

- 1 Because the order of options was randomized, we checked for differences in participants’ usage intentions using only the scenario they were exposed to first (between-subjects). Mirroring the above result, an independent samples t-test found the same significant effect on intention to use with respect to AI that is high (MHigh = 2.56, SD = 1.55) vs. low in autonomy (MLow = 4.77, SD = 1.34); t(188) = −10.53, p < 0.001, d = −1.53.

- 2 Although not pre-registered, we also conducted a simple moderation analysis (PROCESS Model 1; Hayes, 2018) to test whether the effect of AI autonomy on consumers’ AI adoption intentions was moderated by their nationality (US, UK), which was not found to be the case.

- 3 In another experiment, we ruled out that our focal effect was moderated by the product, as hedonic (purchase of a one-week vacation) or utilitarian (purchase of a digital camera; see Study A1 in the Online Appendix).

- 4 To mitigate common method bias, we varied the scale format of our measures (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

- 5 To verify the uniqueness of our proposed chain of effects, we ran an additional moderation analysis (PROCESS Model 1; Hayes, 2018) with personal sense of power as a moderator rather than a mediator (all else equal). We found no signs of moderation. This supports the notion that our AI autonomy manipulation changed participants’ momentary sense of power, which created spillover effects on their AI adoption intentions.

- 6 We actually used two distinct scarcity conditions. In one of them, participants could spend just 7 seconds before making their decision, with the time limit stated as part of the instructions. This time limit mirrors previous manipulations of time constraints (Pieters and Warlop, 1999) and was done to enhance the saliency of time scarcity. The other scarcity condition focused more explicitly on product scarcity, meaning that no objective time constraints existed for participants. While this design difference was originally intended to disentangle the effects of product and time scarcity, we found no difference in consumer choice as a function of these conditions (χ2 < 1). Therefore, following conventions (Frank and Otterbring, 2023; Griskevicius et al., 2009), we combined these conditions into a joint scarcity condition to facilitate parsimonious analyses.