Benefitting from Acquisition Experience During Integration: The Moderating Effect of Strategic M&A Intent

Abstract

Research suggests that M&A performance improves through routinization and/or codified experience. Traditionally, acquisition research has drawn a direct link between the two knowledge accumulation mechanisms and acquisition performance. Yet, how lessons learned are captured and applied in subsequent events remains largely unanswered. We argue that routinization and codification may both result in standardized acquisition integration approaches that promise greater efficiency. Our results show that experience can be captured and applied through standardized acquisition integration approaches. Importantly, our findings show that a strategic M&A intent influences the relationships between routinization and codified experience, and standardized acquisition integration approaches. We find that a strong strategic M&A intent strengthens the relationship between codification and standardization, but it weakens the relationship between routinization and standardization. We test our hypotheses with a combination of primary survey and secondary data to offer managerial and research insights. By combining three pertinent M&A literature streams – acquisition experience, acquisition integration and acquisition intent – we shed light on the importance of organizational learning and strategic direction on acquisition performance.

Introduction

The value of acquisitions is predominantly delivered during integration (Birkinshaw, Bresman and Hakanson, 2000; Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991). There is also an intuitive appeal behind acquisition experience resulting in better integration outcomes. It thus does not come as a surprise that prior M&A research has traditionally assumed a direct link between acquisition experience and performance (Hitt, Harrison and Ireland, 2001; Schweizer et al., 2022). This link may be underpinned by learning from performance feedback (Haleblian, Kim and Rajagopalan, 2006) and the corresponding transfer of practices (Barkema and Schijven, 2008) that ensures a standardized approach to integration. Standardization implies similarity, uniformity and continuity of behaviour and actions (David and Rothwell, 1996), and it helps firms to navigate acquisition integration more efficiently. Standardized integration requires experience to be either codified or embedded in routines (Angwin, Paroutis and Connell, 2015; Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Zollo and Singh, 2004). However, empirical evidence reveals conflicting findings by showing that codification and/or routinization may influence M&A performance both positively and negatively (Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Wright, 2016; Zollo and Singh, 2004). We help to resolve ambiguity regarding the role of experience in acquisition integration.

An initial starting point for unlocking this issue is the insight that the availability of experience (be it codified or routinized) does not necessarily imply that they are actually applied. Indeed, the transfer from experience to application is not automatic and the use of codification or routinization during acquisition integration needs to be carefully coordinated, raising the question of how this is accomplished. Recent research suggests that a firm's M&A intent may act as a coordination device that guides managerial choices regarding the application of codified or routinized acquisition experience (Mirc et al., 2022; Rabier, 2017). M&A intent can provide the coordination needed to overcome the dichotomy managers face when integrating targets (Puranam, Singh and Chaudhuri, 2009) by bridging the chasm between strategic direction, coordination and organizational learning in acquisition integration. We define strategic M&A intent as the extent to which acquisitions play a role in a firm's strategy execution to create value and the importance of acquisitive growth in structured acquisition programmes. A strategic M&A intent provides coordination and direction (Okhuysen and Bechky, 2009; Srikanth and Puranam, 2011) that links various pockets of knowledge and expertise (Friesl and Larty, 2018; Tsoukas, 1996), and it gives managerial action direction and meaning (Okhuysen and Bechky, 2009).

Further, a strategic M&A intent allows managers to create a mental framework that guides processes to avoid costly reversals when integrating a target (Howell, 1970). As a result, a strategic M&A intent allows firms to deploy effective acquisition management or to draw on appropriate experiences. For example, a strategic intent might prevent managers focusing on experience to harvest ‘low-hanging fruit’ or cost savings in innovation-driven acquisitions by maintaining a focus on the strategic idea of the acquisition (Bauer and Friesl, 2022). Hence, we argue that a firm's strategic M&A intent provides a coordination mechanism for acquisition integration. As such, a strategic intent allows firms to pursue routine and codification development viewed as useful to managing acquisition integration.

Our study offers several contributions to acquisition research. First, while previous research treated codified experience and routinization separately (e.g. Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Zollo, 2009; Zollo and Singh, 2004), we argue that codified experience and routinization are complementary yet distinct phenomena. We complement prior research that explicitly focused on codification (Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Zollo and Singh, 2004) or routinization (Becker, 2004; Feldman, 2000) by investigating their combined application (Bingham et al., 2015). This might explain conflicting research findings examining codification or routinization individually. Further, because the impact of codification and routines may vary, firms that use both can combine their strengths and counterbalance their weaknesses.

Second, codified experience and routinization capture what was learned, yet the question remains: How are lessons learned later applied (Vermeulen and Barkema, 2001)? We argue that codified experience and routinization result in standardization of acquisition integration. Standardization gives rise to streamlined integration approaches and procedures that aim to increase performance by reducing complexity and increasing efficiency (Child, 1973; Hackman and Wageman, 1995). This builds on recognition that frequent acquirers, such as Cisco, develop patterns in how they manage acquisitions (Bunnell, 2000; Mayer and Kenney, 2004).

Finally, we argue that learning from acquisition experience and applying lessons learnt requires coordination through a strategic M&A intent that provides direction. However, firms vary concerning their strategic M&A intent, ranging from clear acquisition programmes to opportunistically driven acquisition behaviours (Laamanen and Keil, 2008; Trichterborn, Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß and Schweizer, 2016). As such, we theorize and investigate how a strategic M&A intent moderates the relationships of routinization and codification on the application of integration standardization, jointly contributing to performance. Altogether, we argue and show that codified experience and routinization jointly unfold through standardized integration measures, but these links require coordination through an M&A strategic intent.

Theoretical background

Prior research has built strong connections between codified experience and routinization and the conduct of acquisition management. Both are important in order to cope with the complexity of rare strategic events such as acquisitions (Zollo and Singh, 2004; Zollo and Winter, 2002), with regularly reported failure rates of up to 60% (Homburg and Bucerius, 2005, 2006). Rare strategic events are characterized by increased task complexity, heterogeneity and ambiguity (Zollo and Singh, 2004). In this context, research shows that organizations deploy codification and routinization efforts to overcome challenges.

Codification of experience allows firms to extract lessons learned and to understand cause–effect relationships between managerial actions and acquisition-related outcomes (Zollo and Winter, 2002). This is especially important during acquisition integration that is complex by nature (Cording, Christmann and King, 2008; Vester, 2002). Codified experience enhances managers’ understanding of cause–effect relationships as it captures ‘know-what’ (i.e. presenting content, information and facts), ‘know-how’ (i.e. providing procedures and methodology) and ‘know-why’ (i.e. supporting processes through rational insights, theories and consequences; Foray and Steinmueller, 2003; Håkanson, 2007; Kale and Singh, 2007). This knowledge may be captured in manuals, blueprints, spreadsheets, decision support systems or project management software (Zollo and Winter, 2002). Consequently, codified experience, by revealing action–performance relationships and reducing uncertainty, guides managers through ambiguous and complex tasks, supporting them in their decision-making process – particularly relevant during acquisition integration.

Similar to the codification of knowledge, routinization of activities also reduces uncertainty (Schreyogg and Kliesch-Eberl, 2007) and promises efficiency gains (Eisenhardt, Furr and Bingham, 2010). However, contrary to codified experience, the benefits of routines are realized from the automation of activities (Bargh and Gollwitzer, 1994) and the increased speed of task performance (Wickens and Hollands, 2000). Different from blueprints or manuals, routines allow actors to develop a shared and largely embodied understanding of roles and responsibilities required to perform certain tasks (Feldman and Rafaeli, 2002). This shared understanding enables the building of trust between actors, facilitating knowledge transfer, deal completion and positively affecting acquisition performance (Ahmad et al., 2022; Ranucci and Souder, 2015; Testoni, Sakakibara and Chen, 2022). Consequently, routinized tasks require less conscious effort (Norman and Bobrow, 1975), freeing up managers to deal with non-routine situations (Kanfer and Ackerman, 1989). This is important in tasks related to integration, as routinization can help managers to navigate through complex processes and help them to orchestrate and tune their activities towards efficiency based on a common understanding.

Based on the above, we argue that codified experience is different from routinization, yet they are complementary. We argue that organizations deploy both simultaneously to navigate through acquisition integration challenges. Their combined application can obtain greater benefits in overcoming potential downsides by combining their strengths (Bingham et al., 2015). While codification and routinization are distinct, they can coexist and intertwine. For example, Pentland and Feldman (2005) and D'Adderio (2011) argue that routinization is an antecedent of codification. In addition, researchers reported that codification can break and make routines in firms (Becker and Lazaric, 2009; Miller, Pentland and Choi, 2012). We complement these views by arguing and showing that integration processes can build on both learning mechanisms.

However, it is not sufficient to accumulate experience through codified experience and routinization, as they also need to be applied. For example, codified experiences might remain in folders and drawers or simply not be applied. As a result, we investigate the standardization of integration approaches. Standardization plays a pivotal role in making knowledge applicable and processes more efficient. Prior research argued that standardization allows managers to limit the number of solutions to increase effectiveness and efficiency (Wiegmann, de Vries and Blind, 2017). To overcome complex challenges, such as acquisition integration (Zollo and Winter, 2002), standardization allows us to coordinate between multiple actors and develop a common solution that builds upon past experience (Farrell and Saloner, 1988; Farrell and Simcoe, 2012). By disseminating knowledge throughout a firm and making it applicable, standardization serves as a vital option to develop solutions that are selected out of a wide array of experience (Featherston et al., 2016; Geels, 2004; Ho and O'Sullivan, 2017). As such, standardization affects management and organizational development in general, and how organizations integrate acquired firms in more efficient and effective means (Giacomazzi et al., 1997). The importance of standardization is mirrored by the attributed importance to handbooks or acquisition playbooks (Christensen et al., 2011).

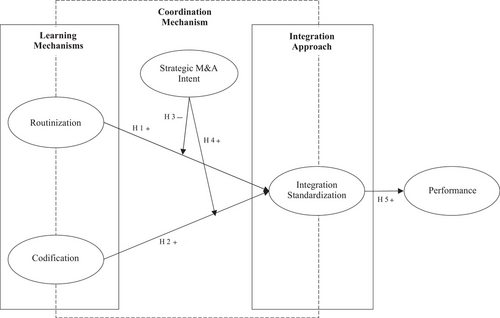

Still, applying accumulated experiences correctly through standardization requires coordination provided by a firm's strategic M&A intent. A firm's strategic intent affects organizational development and its internal processes (Hamel and Prahalad, 1991; Lovas and Ghoshal, 2000). Even though acquisition decisions are a top management responsibility (Trichterborn, Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß and Schweizer, 2016), a strategic M&A intent provides an organization-wide direction, determining resource allocation patterns and the use of competencies (Hamel, Doz and Prahalad, 1989; Mariadoss, Johnson and Martin, 2014). This is particularly important for the decentralized tasks of acquisition integration, where resources are usually drawn from business units and middle managers being involved in integration decisions (Trichterborn, Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß and Schweizer, 2016). Further, Porter et al. (2022) stress the importance of strategic intent, as it combines essential attributes of coordination that motivate and guide employee interactions on work tasks more effectively. Overall, we investigate the interplay of codified experience, routinization, standardization and strategic M&A intent and their joint impacts on acquisition performance (see Figure 1).

Hypothesis development

In the following subsections, we further develop the hypotheses depicted in Figure 1.

Routinization and integration standardization

Consistent with Schweizer et al. (2022), we argue that routinization positively influences learning from acquisitions that is associated with applying standardized acquisition integration approaches. Routinization depends on actors’ common understanding, linking tasks and people through mutual knowledge of ‘what to do’ and ‘what is appropriate’. This enables routinization to coordinate actions through a common understanding in complex settings (Feldman and Rafaeli, 2002; Srikanth and Puranam, 2011). The establishment of a common understanding is the cornerstone for standardization, leading to implicit behavioural knowledge that promotes or penalizes behaviour (Axelrod, 1986; Ouchi, 1980). As a result, shared routines increase trust and help managers diagnose and solve problems (Cannon-Bowers and Salas, 2001), which manifests in standardized integration procedures.

- H1: Routinization increases standardized acquisition integration.

Codified experience and integration standardization

In a meta-analysis, Schweizer et al. (2022) find that performance improvement from acquisition experience depends on efforts to codify knowledge. We argue that a benefit of codified experience is that it contributes to standardization of integration. Codified experience allows for organization-wide dissemination of authorized and officially accepted knowledge (Cowan, David and Foray, 2000) to guide managers through acquisition processes (Zollo and Winter, 2002). It provides managers with know-how, know-what and know-why, fostering a more standardized approach to acquisition integration (DeHart-Davis, Chen and Little, 2013; March, Schulz and Zhou, 2000).

- H2: Codified experience increases standardized acquisition integration.

An orchestrating effect of strategic M&A intent

We argue that strategic M&A intent affects the deployment of integration standardization, as it prioritizes the importance of acquisitions relative to other strategic endeavours. Thus, a strategic M&A intent constitutes a shared understanding that directs and coordinates activities towards common goals (Lovas and Ghoshal, 2000). This shared understanding of goals to grow through acquisitions is essential for integration tasks that become aligned through bottom-up initiatives that weigh opportunities (Lovas and Ghoshal, 2000; Noda and Bower, 1996) and direct necessary competencies (Hamel, Doz and Prahalad, 1989). As a result, a strategic M&A intent coordinates how routinization and codification are applied through managerial bottom-up initiatives that align tasks, knowledge and their subsequent standardization, towards the intended goal. As a result, a strategic M&A intent moderates the role of codified experience and routinization on standardization. However, we anticipate that the impact varies.

- H3: Strategic M&A intent negatively moderates the relationship between routinization and standardized acquisition integration.

- H4: Strategic M&A intent positively moderates the relationship between codified experience and standardized acquisition integration.

Integration standardization and performance

While there is a trade-off between adaptability and efficiency (Weigelt and Sarkar, 2012), standards in general are beneficial for firms and contribute to increased performance through increased efficiency. For example, Gary and Wood (2011) observe that standardization improves decision-making in uncertain business environments, and therefore increases firm performance. Additionally, standards improve goal-setting in organizations, leading to improved employee performance (Squires and Wilders, 2010). Further, standards are not only important to achieve strategic goals such as internationalization and corporate social responsibly (McWilliams and Spegel, 2000; Valentine and Fleischman, 2008), they also indirectly contribute to firm performance by increasing the efficiency of activities (Tassey, 2000), as standards can be applied by all members of the organization (Rasche, 2010).

- H5: Standardization of integration increases acquisition performance.

Methodology

Sample and data

For testing our theoretical model, we collected primary data from 113 manufacturing firms from the German-speaking countries that have been active in the market for corporate control. A focus on manufacturing was theoretically driven, as standardization is more common for manufacturing firms that typically apply quality standards (e.g. ISO certification) and closely monitor production processes. Data collection was conducted in spring 2017. We used a mail and Internet survey methodology for primary data collection, and publicly available accounting data. The goal of the survey was to contact CEOs or responsible managers (heads of corporate development and M&A departments) who were actively involved in acquisitions. We chose our contacts based on the Zephyr database from the Bureau van Dijk, providing comprehensive and recent information on M&A deals and contact data.

As acquisitions differ (Bower, 2001), we refrain from comparing the outcomes of different acquisitions. In our survey, we focused on industrial companies with headquarters located in Germany, Austria and Switzerland that were active on the market for corporate control between 2011 and 2016 for several reasons. First, we restricted our respondents to German-speaking firms in central Europe to limit the effects of cultural (Stahl and Voigt, 2008) and language (Kedia and Reddy, 2016) differences. Second, Germanic countries are characterized by strict labour regulations that make integration more complex compared to rather free-economy countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. Germanic countries provide a rather similar institutional setting that makes acquisitions and their legal framework (e.g. labour regulations, etc.) comparable (Botero et al., 2004). Third, industrial companies usually have longer lifecycles, extended planning horizons and a longstanding international footprint (De Massis et al., 2018). We focused on industrial companies where standardization matters more compared to other industries. As such, the sampled firms can be described as typical firms of the German ‘Mittelstand’ that have a longstanding track record on the market for corporate control.

We also restricted our sample to small and medium enterprises (SMEs), as larger firms are more likely to have formalized processes (Døving and Gooderham, 2008), or extending our sample beyond SMEs would show less variation in our variables of interest (i.e. routinization and codification). Acquisition events matter more for smaller firms compared to large multinational enterprises. In addition, we deliberately considered a range of acquirers with a variety of acquisition experience. This sampling structure is appropriate as our paper aims to understand how firms deploy routinization and codified experience based on varying acquisition experience. On average, the firms in our sample have acquired between three and four firms within 5 years prior to the acquisition referred to in the questionnaire. Our sample timeframe guarantees that a firm was actively involved in an ongoing integration process that would either be in a final stage or already completed (Ellis, Reus and Lamont, 2009; Homburg and Bucerius, 2005; Zollo and Meier, 2008). Additionally, it minimizes the risk of recollection bias (Ellis, Reus and Lamont, 2009; Krishnan, Hitt and Park, 2007).

To validate our survey, we adapted a two-step pre-test in February 2017 with M&A managers, CEOs and academics (Churchill, 1995), resulting in adding examples and clarifying terms that were difficult to understand. We identified 609 companies fitting to our sampling criteria, and our response rate of 18.56% is in line with other primary data M&A studies (Capron and Mitchell, 1998; Engelen et al., 2015; Homburg and Bucerius, 2006). Overall, we received 113 questionnaires from individual acquires. Most companies in our sample generated annual sales between 100 and 499 million euros and employed between 251 and 5000 people. More than 49% of the firms that replied were family owned and older than 31 years. This reflects the larger population of firms well. For assessing potential nonresponse bias, we implemented two different tests. First, we compared the demographic data of our sample (e.g. firm size in terms of annual sales and relative size of the target firms) with secondary data from a randomly chosen subset of the companies that fit our sampling criteria. Second, we compared early and late respondents (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). Both tests show no significant differences, indicating that nonresponse bias is not a serious issue for our data. See Table 1 for an overview of the descriptive statistics.

Measurement development

For measurement model operationalization we largely relied on existing scales, modified to fit our research context. One measurement model is newly developed.

Codified experience

Codified experience is a central construct in management research. In our study we rely on the measurement used by Dhanaraj et al. (2004), assessing the codified experience in organizations. We modified this scale in such a way that it fits the M&A context. The modified construct identifies codification experience through three items: measuring to what extent (1) documents provide insights on the M&A process; (2) manuals guide on the process; and (3) experience of applied management has been documented. Codification experience is assessed on a seven-point scale.

Routinization

Routinization used the measurement model developed by Withey, Daft and Cooper (1983) with a seven-point Likert scale. As the original construct was developed for the marketing context, we modified the items in such a way that they fit the acquisition context. The construct operationalizes routinization, with five items measuring to what extent: (1) integration tasks are similar in various acquisitions; (2) integration projects are routine jobs; (3) integration tasks are handled in the same manner; (4) team members of the integration team perform repetitive activities; and (5) there is a similar sequence of tasks from integration to integration.

Integration standardization

We modified the measurement model developed by Zaheer, Castañer and Souder (2013) to assess the degree to which integration follows a standardized procedure on a seven-point Likert scale. The construct identifies standardization of integration through four items, measuring to what extent organizations rely on standardization over individualization when integrating: (1) strategy formulation; (2) marketing; (3) research and development; and (4) operations. This scale focuses on how structural integration can offer greater repeatability than human integration (Birkinshaw, Bresman and Hakanson, 2000).

Strategic M&A intent

We assessed the strategic M&A by the strategic importance of acquisitions for the organization (e.g. Achtenhagen, Brunninge and Melin, 2017; Hitt et al., 1996) on a seven-point Likert scale. Strategic M&A intent used three indicators: (1) what contributes to your firm growth (organic vs acquisitive); (2) is the growth of the firm based on a strong acquisition programme; and (3) the share of acquired sales in the past 5 years.

Performance

Acquisition performance is a theoretically complex construct (Cording, Christmann and Weigelt, 2010) and it has been assessed by stock market, accounting and survey-based measures. Interestingly, studies show that different measures share only a little variance (Cording, Christmann and Weigelt, 2010; Meglio and Risberg, 2011; Zollo and Meier, 2008). Despite the criticism of survey-based measures, their use to evaluate acquisition performance offers comparable results to other measures (Ellis, Reus and Lamont, 2009; King et al., 2021), as well as offering an advantage of assessing multiple dimensions of performance (Papadakis and Thanos, 2010). For example, we focus on the achievement of strategic goals compared to major competitors. This is in line with previous research in M&A (Lisboa, Skarmeas and Lages, 2011; Trichterborn, Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß and Schweizer, 2016; Vorheis and Morgan, 2005) and we assess performance with four indicators comparing the acquirer's performance to major competitors using the scale developed by Trichterborn, Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß and Schweizer (2016). On a seven-point Likert scale we assessed: (1) development of sales; (2) market share; (3) operating margin; and (4) synergy realization. It is important to note that the performance distribution in our sample reflects the reported performance rates of the investigated industries well. To check for skewness due to common and key informant bias, we also collected secondary data for firms where respondents added their contact details and data was available for triangulation. From a subsample of 13%, we collected cumulative abnormal growth rates from 2012 to 2016. The items of our performance measure correlate highly with the secondary data measure (e.g. synergy realization: correlation coefficient = 0.482; p = 0.035 one-sided). This gives us reason to believe that problems associated with single-source surveys are not a serious issue for our data.

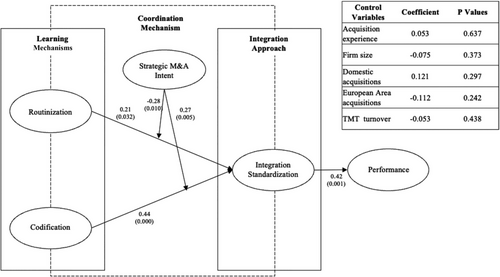

Controls

As our research model is potentially sensitive to model specification, we used a range of control variables. First, we control for the dominant acquisition focus of the acquiring organization. As such, we ask for the share of acquisitions that is (1) domestic or in the European Economic Area or (2) outside these areas. This is important as the first two areas provide similar and familiar institutional contexts that differ from the latter one. These contexts might provide firms with different lessons learned and require different application. Second, firm size in terms of the number of employees and sales is also important, as firm size is an indicator of formalization and stricter rules. Third, top management turnover might have a direct effect on key learnings from previous acquisitions and on the application of integration rules. Fourth, acquisition experience is the foundation for routine development and rule application during integration. We find that the control variables do not affect our results. The control variables and values are presented in Figure 2. In line with previous studies, we assess the number of acquisitions conducted in the past 5 years as an indicator of acquisition experience. A description of the items and the psychometric properties of the scales can be found in the Appendix.

Analysis and results

Common method bias

Having collected information about our dependent and independent variables with the same survey instrument, common method bias might be a serious issue for our data. As Podsakoff et al. (2003) state, common method bias is the main source of measurement errors. To mitigate the risk for common method bias, we implemented various a priori measures (Chang, Van Witteloostuijn and Eden, 2020), such as separating the variables to reduce proximity effects (Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff, 2012) and applying latent variable measurement (Harrison, McLaughlin and Coalter, 1996). Further, we changed or modified the scale endpoints to reduce response patterns (Podsakoff et al., 2003). With the data at hand, we applied several statistical remedies to assess a potential common method bias. The Harman's single-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986) is suitable to test for common method bias since it utilizes a single-factor analysis capturing the covariance between the independent and dependent variables. The data of our survey cannot be attributed to a single factor. When analysed in a factor analysis, we identify eight distinct factors. Additionally, we applied the ad hoc approach suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003). We followed the guidelines developed by Liang et al. (2007) and included a common method factor in our structural model consisting of all indicators included in the model constructs. The ratio of substantive factor loadings and method factor loadings is 129 to 1. These results indicate that common method bias is not a serious issue. Last, we collected secondary data for a subsample (13%) that highly correlates with our performance measure. The combined results do not suggest that common method bias influences our results.

Analytical method

We apply structural equation modelling for testing our research model. Instead of a covariance-based approach, we apply a variance-based approach computed thought Smart PLS (Ringle, Wende and Will, 2005). There are several reasons for choosing this approach. First, PLS is adequate for complex models (Haenlein and Kaplan, 2004). Second, sample size requirements are lower (Fornell and Bookstein, 1982; Haenlein and Kaplan, 2004; Tenenhaus et al., 2005). Third, PLS provides a higher degree of predictability when optimizing the dependent variable, which in our case is performance. Also, we utilized the two-step approach suggested by Agarwal and Karahanna (2000) consisting of two independent approximations, one for the measurement models and one for the analysis of the relationships. To ratify our research model, we followed the guidelines of Hulland (1999) assessing the measurement and the structural model.

Evaluating the measurement models

First, we evaluated the measurement models. All indicators of our latent variables (apart from four) have loadings above the recommended threshold of 0.7. One indicator of the construct integration routines has a value of 0.682 and two indicators of the latent variable strategic M&A intent have a value of 0.408 or 0.692. Even though these indicators’ loadings are below the threshold, we decided to keep them in the analysis (Hulland, 1999). Further, construct validity is established as the average variance extracted (AVE) values are all above the 0.5 threshold. Next, we assessed discriminant validity on the indicator and construct level (Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics, 2009; Hulland, 1999). The Fornell–Larcker criterion (see Table 1,2; Fornell and Larcker, 1981), as well as the cross-loadings criterion, is fulfilled. Additionally, the heterotrait to monotrait ratio is, with the greatest value of 0.711, far below the recommended threshold. Overall, discriminant validity is established.

| Previous acquisitions | (%) | Previous divestments | (%) | Annual sales (€ mn) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 11.5 | None | 61.1 | <25 | 12.4 |

| 1–2 | 24.8 | 1–2 | 23.9 | 25–49 | 8.0 |

| 3–4 | 27.4 | 3–4 | 12.3 | 50–99 | 14.2 |

| 5–6 | 14.2 | 5–6 | 0.9 | 100–249 | 22.1 |

| 7–8 | 1.8 | 7–8 | 0.9 | 250–499 | 23.0 |

| >8 | 20.4 | >8 | 0.9 | 500–1000 | 8.0 |

| >1000 | 12.4 | ||||

| Firm age (years) | (%) | Majority owner | (%) | Number of employees | (%) |

| 1–5 | 2.7 | Family firm | 49.6 | 1–50 | 4.4 |

| 6–10 | 1.8 | Private firm | 27.4 | 51–100 | 4.4 |

| 11–15 | 3.5 | Listed firm | 13.3 | 101–250 | 8.0 |

| 16–20 | 8.8 | Institutionally owned | 9.7 | 251–500 | 21.2 |

| 21–25 | 17.7 | 501–1000 | 18.6 | ||

| 26–30 | 18.6 | 1001–5000 | 24.8 | ||

| >30 | 46.9 | >5000 | 18.6 |

| Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Codified experience | 0.440 | 0.077 | 0.823 | |||||||||||

| (2) | EEA acquisitions | −0.112 | 0.095 | 0.189 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (3) | Intent | −0.079 | 0.054 | 0.298 | 0.379 | 0.678 | |||||||||

| (4) | Intent_Codification | 0.269 | 0.096 | 0.076 | 0.145 | 0.178 | 0.565 | ||||||||

| (5) | Intent_Routinization | −0.276 | 0.107 | −0.042 | 0.035 | −0.134 | 0.263 | 0.633 | |||||||

| (6) | Performance | 0.221 | 0.103 | 0.308 | −0.005 | 0.110 | 0.142 | −0.024 | 0.789 | ||||||

| (7) | Routinization | 0.416 | 0.125 | 0.470 | 0.126 | 0.321 | 0.030 | −0.134 | 0.373 | 0.772 | |||||

| (8) | Standardization | −0.053 | 0.069 | 0.556 | 0.084 | 0.216 | 0.229 | −0.278 | 0.431 | 0.453 | 0.781 | ||||

| (9) | TMT turnover | 0.053 | 0.112 | 0.123 | −0.019 | −0.122 | 0.072 | 0.199 | −0.067 | 0.024 | −0.035 | 1.000 | |||

| (10) | Acquisition experience | 0.121 | 0.116 | 0.365 | 0.558 | 0.313 | −0.002 | −0.091 | 0.149 | 0.186 | 0.234 | 0.065 | 1.000 | ||

| (11) | Domestic acquisitions | −0.075 | 0.084 | 0.288 | 0.487 | 0.372 | 0.069 | 0.040 | 0.158 | 0.245 | 0.175 | 0.007 | 0.773 | 1.000 | |

| (12) | Firm size | 0.440 | 0.077 | 0.326 | 0.238 | 0.100 | 0.061 | −0.157 | 0.017 | 0.187 | 0.157 | 0.077 | 0.397 | 0.299 | 1.000 |

Structural model and hypothesis testing

Figure 2 displays the results of the PLS analysis. Our research model can explain a substantial amount of variance of performance (R2 = 0.209) and the application of standardized integration approaches (R2 = 0.481). Further, the analysis of the Stone–Geisser criterion reveals that our results reconstruct the hypothesized effects in a substantive way (all values exceed the threshold of 0). For testing the hypotheses, we applied the standard PLS algorithm. For assessing the significance of the relationships, we ran the bootstrapping procedure with 5000 bootstraps, applying the individual sign changes option.

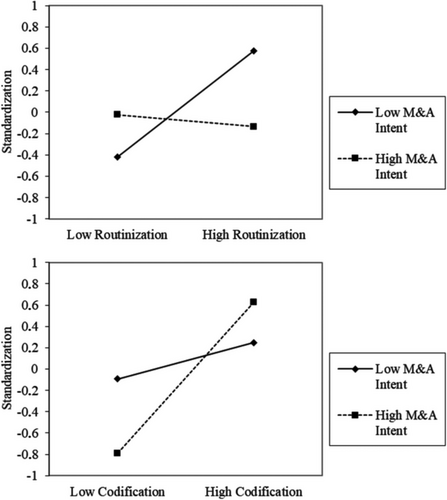

For H1, we find empirical evidence that routinization results in standardized acquisition integration (β = 0.221; p = 0.032). We find support for H2 (β = 0.440; p = 0.000), indicating that codified experience may result in greater application of integration standardization. For H3, we find empirical support for strategic M&A intent negatively moderating the relationship between routinization and integration standardization (β = −0.276; p = 0.010). For H4, we also find empirical support of strategic M&A intent positively moderating the relationship between codification and integration standardization (β = 0.269; p = 0.005). Figure 3 shows the interaction effects. Further, supporting H5, we find evidence for a positive and significant effect of standardized acquisition integration on performance (β = 0.416; p = 0.001). This result suggests that standardized integration can improve acquisition performance.

Our control variables remain insignificant on standardization and performance, indicating that the application of standardized acquisition approaches is not directly impacted by different types of experience (domestic, EEA or total amount of experience), managerial turnover or firm size, but rather by codification and routinization. Further, this is in line with previous research showing that acquisition experience (as a count of past acquisitions) is not significantly linked to performance (King et al., 2021), unless acquisition experience is codified (Schweizer et al., 2022).

As routinization and codification might have direct effects on performance, we run an additional analysis to test for potential mediation. To test mediation, we investigated the bias-corrected confidence intervals (Bc CI) (Efron, 1987; Efron and Tibshirani, 1986). We followed the suggestions of Zhao et al. (2010) and find that standardization fully mediates the effect of codification on performance, while routinization might be partially mediated. As the direct effect of codification is insignificant and zero does not occur in the Bc CI of the indirect effect, we find that standardization fully mediates the effect. For routinization, we find that the direct effect on performance is significant. However, as zero does not occur in the Bc CI of the indirect effect, we assume that standardization partially mediates the effect on performance. Table 3 displays the results of the mediation analysis, and it suggests an indirect effect of codification and a direct effect of routinization on acquisition performance, providing additional support for H4 and H1, respectively.

| Effect | Estimate | T statistics | p Level | 95 Bc CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect: codification → performance | 0.059 | 0.719 | n.s. | 0.000–0.205 |

| Indirect effect: codification → performance | 0.123 | 1.939 | 0.053 | 0.022–0.270 |

| Total effect: codification → performance | 0.182 | 1.870 | 0.062 | 0.016–0.388 |

| Direct effect: routinization → performance | 0.244 | 1.946 | 0.052 | 0.014–0.482 |

| Indirect effect: routinization → performance | 0.059 | 1.234 | n.s. | 0.005–0.227 |

| Total effect: routinization → performance | 0.303 | 2.392 | 0.017 | 0.031–0.530 |

Robustness checks

Having implemented multiple control variables in our empirical model, we are confronted with the risk of overfitting. As a result, we calculated reduced and extended models to see if our results remain stable. Our hypothesized relationships remain stable across extended and reduced models, validating our results. Further, our data might be affected by multicollinearity. As such, we investigated variance inflation factors (VIFs). The highest VIF value is 2.2 and thus far below the recommended threshold of 10. Finally, our results might be affected by simultaneous causality (e.g. performance could serve as a feedback loop for routinization, codification and standardization) or omitted variable bias (e.g. a firm might have a specific M&A capability). Therefore, we conducted an instrumental variable analysis with 2SLS regressions (Bascle, 2008) and five instrumental variables. We used the EndoS macro for SPSSA (Darvanto, 2020). After confirming that instrument strength and Sargan's J-statistic exceed the recommended thresholds, we used the predicted values in an ordinary least squares regression to verify our results. These tests indicate that our presented analysis and results are not biased (Davidson and Mackinnon, 1983).

Discussion

We connect codified experience and routinization through how they are applied with standardization, and then coordinated by a strategic M&A intent. Our results advance scholarly understanding of acquisitions by jointly considering the role of codified experience and routinization in acquisition integration. In contrast to prior research that traditionally focuses on either codification (Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Zollo and Winter, 2002) or routinization (Basuil and Datta, 2015; Lazaric and Denis, 2005), we confirm the research of Schweizer et al. (2022) by showing that both concepts are important and coexist. Thus, we contribute to existing research in three primary ways. First, separate consideration of acquisition experience, codification and routines in existing research begins to explain conflicting research results, as we find that the processes and their application are intertwined. Second, their coexistence matters as firms can apply routinization and codified experience differently to counterbalance the negative effects of each one and combine their mutual strengths. Third, a firm's M&A strategic intent impacts the role of codification and routinization differently.

Research implications

A complex system of knowledge is required to manage acquisition integration. While formalized codified experience enables transparency, organization-wide stability and guidance, they lack in flexibility (Gersick and Hackman, 1990; Weiss and Ilgen, 1985) and constitute probably a source of inertia (Hannan and Freeman, 1984). Contrarily, but in line with routine theory (Feldman and Pentland, 2003), we find that routinization allows for flexibility through case-by-case management. Paradoxically, the management of acquisition integration demands both codified experience and routinization working together to balance conflicting requirements that characterize acquisitions as project management (Vester, 2002). Notably, codified experience and routinization reflect what is learned, but not how it is applied.

Following Vermeulen and Barkema (2001), who stress the importance of research that unravels what organizations learn and how they apply it, we confirm a need to open the experience–performance relationship black box. While research on codification and routines in acquisitions has advanced our understanding of how experiences are transferred to lessons learned, little is known about how this is applied in subsequent acquisitions. That matters, because research on codification and routinization in acquisitions still provides conflicting results (Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates, 2012; Zollo, 2009), implying more complex relationships than previously assumed. We develop and show that the application of standardization and M&A intent represents missing links.

Simply, having codified experience and routinization does not imply that they are activated and actually applied (Collinson and Wilson, 2006). For example, while checklists may sit comfortably in folders and drawers, it is only when they are enacted in the form of applied standards that they shape acquisition outcomes. Interestingly, prior research outlines the importance of standardization in acquisition integration. For example, Angwin and Meadow (2015) show that firms choose different standardized integration approaches to achieve explorative or exploitative goals. Moreover, Heimeriks et al. (2012) stress the importance of standardized acquisition integration practices to counter codification disadvantages. This is supported by our empirical evidence showing that codification impacts acquisition performance indirectly through standardization, and our results indicate that routines also trigger standardization. A distinction that sheds light on the ecology of knowledge within a firm and learning pathways for unique knowledge. These findings complement research emphasizing the importance of codified knowledge for acquisition (Zollo, 2009; Zollo and Winter, 2002) by stressing the importance of standardization for codification to be effective. Combined, we give empirical evidence that codified experience and routinization result in standardization of integration.

Further, strategy research increasingly highlights the role of strategic intent for various domains (e.g. how firms build on capabilities, form alliances and learn; Edelman, Brush and Manolova, 2005; Hamel and Prahalad, 1996; Porter et al., 2022). For acquisitions, we argue that the relationship between knowledge and standardization is contingent on the strategic direction of a firm. This is important, as acquisitions constitute rare and complex strategic decisions that require an array of sequential but interrelated decisions. Without a clear direction, the gravitational forces of these interrelated decisions endanger coherence and acquisition outcomes. This aligns with research that stresses the importance of a strategic intent for firms to foster organizational coordination (Hamel, Doz and Prahalad, 1989; Mariadoss, Johnson and Martin, 2014) and interlink strategic motives with organizational learning (Chen and Yeh, 2012; Fathei and Englis, 2012).

While only limited research studies strategic intention and learning from acquisitions (Chen and Yeh, 2012; Fathei and Englis, 2012), we provide evidence that a strategic M&A intent enhances or reduces the relationships of codified experience or routinization on the application of standards. During integration, a strategic M&A intent strengthens the effects of codified experience, while reducing the effects of routinization on standardization. A strategic M&A intent channels a complex array of sequential and interrelated decisions, triggering the effect of codified experience on applied standards. Meanwhile, the coordinating effect of a strategic M&A intent challenges routines to become a standard. Routinization is based on decentralized tacit knowledge acquired through collective learning (Brown and Duguid, 1991; Nelson, 1985), which in turn is more difficult to control and align towards a strategic intent. Thus, a strategic M&A intent mitigates the application of standardized integration approaches based on routinization. We show this in the context of M&A research, but similar effects have been found for resource allocation patterns in strategy development (Burgelman, 1983, 2002). Combined, while a strategic M&A intent defines the strategic direction, it might limit the necessary degrees of freedom in decision-making in situations where flexibility is needed. Additional research on associated relationships is needed.

Managerial implications

Our study is also relevant for managers responsible for acquisition planning and implementation. Managers can utilize codified experience and routinization to deal with the complexity and uncertainty of acquisition integration. However, managers need to carefully choose combinations of routinization and codification, to align them with a firm's strategic M&A intent. A clear strategic direction encourages managers to rely more strongly on codified experience, but it hampers the application of dispersed routines that might also be beneficial. If not aligned, managers run the danger of over-reliance on given practices, rather than customizing for the needs of the acquisition. We also provide evidence that a strategic M&A intent, ranging from opportunistic acquisitions to clear acquisition programmes, frames how managers apply experience.

Limitations and future research

The strategic contribution of an acquisition is dependent on integration that takes 3 to 5 years (Ellis, Reus and Lamont, 2009). Consequently, acquisition research based on survey data is faced with the conflict of reliable measurements due to the capacity for recollection. Consequently, we restricted our sample to acquisitions that took place between 2011 and 2016, to make sure that respondents were still able to refer to the acquisition. In addition, a longitudinal research design would be superior to a cross-sectional design. Still, managerial turnover in the post-merger phase and the problem of managers lacking willingness to participate in surveys over a long period makes longitudinal studies in the context of acquisitions potentially impractical. Additionally, to measure the impact of acquisition integration on organizations, a period of 3 to 5 years is suggested (Ellis, Reus and Lamont, 2009; Homburg and Bucerius, 2005; Zollo and Meier, 2008), imposing additional complications on implementing a longitudinal design. Lastly, the number of observations and the statistical power correlate and thus might impose a limitation. However, as this is the first paper to combine observations for routinization, codified experience and standardization in the context of acquisitions, additional research is needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

We find strong evidence that routinization, codified experience and standardized integration approaches are important considerations when firms conduct acquisitions. We show that standardization, based on routinization and codified experience, is highly relevant in driving performance. This suggests that more scholarly attention is needed to jointly consider routines and codification in the context of acquisitions. We also show that a firm's M&A intent really matters, as it influences how routines and codified experience are applied. We hope that our study will stimulate further research on applied learning and coordination in the context of acquisitions.

Biographies

Yves-Martin Felker is an Assistant Professor of Strategic Management at California State University, Los Angeles. His research focuses on CEO personality and M&As.

Florian Bauer is a Professor and Sir Roland Chair in Strategic Management at Lancaster University. His strategy research focuses on M&A decision-making.

Martin Friesl is Professor of Strategy and Organization at the University of Bamberg and Adjunct Professor at NHH Norwegian School of Economics. His research focuses on strategic renewal, strategy implementation and the development, change and replication of organizational capabilities.

David R. King is the Higdon Professor of Management at the College of Business, Florida State University. His primary research interest is M&A activity and performance.