Strategic Activity as Bundled Affordances

Abstract

This study addresses the question of how strategy actors instil strategic behaviour in everyday strategic activity despite their physical absence. To do this, I draw on ecological psychology and introduce the concept of bundled affordances, multiple spatiotemporally distinct yet co-performing action possibilities offered to strategists in single strategic events. Through an in-depth qualitative study of three affiliated banks, I illustrate that affordances can be usefully bundled when familiar features of material objects are placed in the everyday perceptual field of strategists. The study further suggests that when corporate interests and individual goals are effectively entangled into affordance bundles, they not only motivate individuals to behave strategically but also make those actions intuitive rather than open-ended action possibilities, instructive rather than interpretive, and readily identifiable in events rather than in information about the properties of material objects.

Introduction

Strategy practice and strategizing have widely been accepted as the daily work of making, shaping and executing strategies (Whittington, 1996, 2006) within and across organizational hierarchies (Floyd and Lane, 2000; Mantere, 2005; Regnér, 2003). However, while prior studies of strategy practices have reflected the social systems in which strategies are shaped (Whittington, 1993), giving ontological primacy to human agency, calls have recently been made to study the mutual constitution of social and material agencies as the ontological underpinning for strategizing (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Kaplan, 2011). The main argument of this ‘sociomaterial’ view is to overcome subject–object dualisms (Chia and Holt, 2006; Chia and Rasche, 2010) and reconsider their ‘co-performance’ (Pels, Hetherington and Vandenberghe, 2002) when making intelligible practice arrangements (Sandberg and Tsoukas, 2011).

In this light, strategy practice scholars have shown interest in the ‘material resources of strategy activity’ (Vaara and Whittington, 2012), with particular interest in studying the material agencies of strategy texts (e.g. Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010) displayed in documents and various technologies (e.g. Eppler and Platts, 2009; Giraudeau, 2008; Kaplan, 2011). However, prior studies have addressed material agency as being contingent upon human agency, suggesting that actors' strategic intent and interpretations of strategy texts and technologies lead them to act in certain ways rather than consider the possibilities for action afforded by the strategy objects themselves. In this study, I show that strategic activity is contingent upon solicitations between strategy actors and objects and that such solicitations unfold instructive rather than interpretable action possibilities. In addition, in contrast to observing isolated subject–object solicitations, I show that such affordances (Gibson, 1979) come in bundles in strategic events, which are considered as notable occurrences that intelligibly bring meaning to action (Schatzki, 2010). This approach helps us to consider the event as the locus of invariant information that prompts strategic behaviour rather than some property of the object or actors' interpretations of it. The focus on strategic events further suggests the possibility of displaced agency such that subjects and objects need not be spatiotemporally present for action to occur.

In illustrating this idea, the aim of this study is to offer a way of understanding strategic activity as a spatiotemporally separate and separable bundle of subject–object solicitations. Understanding this important feature of distributed sociomaterial agency in strategizing is important as it strikes a balance between assumptions of interpretations of material agency on the one hand and the instructive nature of objects on the other. The concept of affordances (Gibson, 1977) suggests a solution to deal with material agency by considering social and material agency as complementary agential sources for which action possibilities are prompted from subject–object solicitations. In extending this notion of affordances, I show how strategic action possibilities appear in bundles that transcend the immediate time–space presence of subjects and objects. I provide a detailed illustration of how practice affordances present themselves in a conjoined fashion through an in-depth study based on site observations and interviews at three affiliated banks.

In the next section, I briefly discuss some relevant studies attending to the material agency of strategy and then propose the concept of affordances as an alternative view. Next, the research sites, methods and modes of analysis are presented. Then I present the findings, and the following section is devoted to discussing the findings and expanding their implications for the current thinking on strategy. Finally, the paper closes with conclusions and implications for future research.

Theory

Material accounts of strategy practice have recently begun to balance the view that strategy practices reflect the social systems in which they are shaped (Whittington, 1993). Drawing on a variety of approaches, these studies have focused on the textual dimension of material agency and the resultant effects on the practice of strategic planning. This research has largely found that strategy texts affect strategic planning by being self-authorizing, disciplining, structuring, and selective in practice.

The self-authorizing character of textual agency stems from the view that textual accounts of phenomena, ideas, ideologies, objects etc. gain a referential power once they communicate a common meaning in a given domain of practice (Ricoeur, 1981). For example, Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli (2010) found that strategy plans have such endemic self-authorizing characteristics that the strategy group of a Finnish city organization prioritized their strategy plan over undertaking other administrative tasks. Similarly, Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) studied the recursive relationship between talk and text in the strategic planning process and found that textual representations increasingly guide both the content and order of discussions. These examples suggest that strategy is a technology of power ‘that creates as much as it responds to the problems it professes to resolve’ (Knights and Morgan, 1991, p. 260).

Strategy texts also have disciplining tendencies. For instance, Mantere and Vaara (2008) found that the disciplining capacity of strategy discourse constructs hierarchies and command structures that mark the inclusion and exclusion of actors in strategy processes. Along these same lines, Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli (2010) observed that the strategy vocabulary developed during the strategic planning process serves to systematize subsequent discussions and decision making. Similarly, Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) found that planning texts discipline the order and topics of communication during planning sessions.

Textual agency also has structuring effects on strategic planning activity. For example, Giraudeau (2008) found that when the carmaker Renault set up a strategic plan for the Brazilian market, the document contained bullet points organized in a logical sequence of corporate actions. This resulted in the systematic ordering of strategic actions and a unifying title, ‘Renault Strategy’. Along similar lines, the Finnish city organization studied by Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli (2010) was provided with strategy concepts (e.g. SWOT) that structured meeting agendas and provided a systematic strategy conversation between the members of the group. These studies subscribe to the view that strategy texts have the capacity to ‘structure thinking’ (Kaplan, 2011, p. 328), order actions, communicate, and set meeting agendas.

A final characteristic of textual agency in strategy plans is their liability of selectiveness. For example, in an illustrative example from an informant's personal diary, Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli (2010, p. 692) showed that words ‘of foreign origin such as “scenario” hamper understanding and commitment’. Conversely, both Giraudeau (2008) and Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) found that strategy texts could also be authored such that they increase readers' interpretive flexibility and thereby imbue strategic alignment and a sense of inclusion between levels and functions of an organization. These examples of the selecting characteristics of textual agency point to what Kaplan (2011) termed ‘cartography’, or the balancing act of including and excluding strategic ideas, information and strategy actors.

While these studies have shown a variety of action possibilities emanating from authoring, reading and editing a text, they have fallen short on two points. First, these studies have treated texts as ‘phenomenal objects’ (Gibson, 1982) such that their material agency is contingent upon the strategists' subjective experience and interpretations of the sometimes ‘manipulative rhetorical constructions’ (Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010, p. 694) of strategy texts and their ‘structure and content’ (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011, p. 1227). Thus, how strategy actors respond depends on their cognitive sensemaking processes with regard to the assumed variability of meanings of texts rather than an exploration of their direct ‘actionability’.

Second, prior studies have treated material agency as a phenomenon that is physically proximate to individual agency, is dependent on the direct relationship between subjects and objects and is assumed to have a proximate relevance. However, prior studies have shown that strategizing is a displaced activity (Whittington, Cailluet and Yakis-Douglas, 2011) involving many actors both within and outside the organization (Paroutis and Pettigrew, 2007; Regnér, 2003). The field of strategy has thereby neglected the possibility that strategic action is constituted by enactments of objects that are spatially and temporally detached from the actual event. One way to overcome this limitation is to view social and material agency in terms of affordances (Gibson, 1979), which has gained momentum in such scholarly traditions as organizational form and function (Zammuto et al., 2007), information systems design (Zhang, 2008) and routine flexibility (Leonardi, 2011). Following these earlier attempts, I draw on research in ecological psychology to suggest that strategic activity can usefully be viewed as affordances.

Affordances

The concept of affordances was coined by J. J. Gibson (1977), who attempted to bridge the subject–object dichotomy by suggesting that agency resides in both subjects and objects. Gibson (1979) theorized that agency is mutually constitutive of actors' perceptual capacity of observing possibilities for action, their bodily dispositions to act in a certain way, and the observed environments and objects that correspond to their physical action capacities. When construed as both a ‘fact of the environment and a fact of behavior’ (Gibson, 1979, p. 129), affordances call for opportunities for action, prompting certain behaviours while controlling and constraining others. Gibson (1979) further argued that the meaning of an object (e.g. environmental, animate, edible, manufactured) – namely, what it offers to do (or not to do) – is observed before its substance or its qualities. For example, one first observes a pen as something to write with before considering the physical materials it is made of (Gibson, 1979).

Objects, therefore, prompt action in a multitude of ways based on how they are designed or shaped and what role they play in practice. However, while affordances may differ across practices, ‘they cannot be seen as freely variable’ (Hutchby, 2001, p. 447). For example, a corporate annual report affords credit analysis for a bank advisor in the practice of credit decisions but affords corporate valuation to an investor in the practice of due diligence. Indeed, whereas objects have many affordances, it is the ‘awareness of what things afford and the concomitant ability to select, find, and extract relevant affordances from the environment’ (Reed, 1996, p. 119, emphasis added) that reduces the variability of affordances. As Reed (1996) argued, the meaning and value of an affordance for an observer is realized once it has been detected and used since the information residing in affordances has caught the observer's attention and thus co-presents with his or her motivations (Gibson, 1979).

Affordances can therefore motivate skilled individuals to act and become aware of action possibilities (Reed, 1996). Information systems scholars have advanced this view by suggesting the concept of ‘motivational affordance’ as a design principle to help augment computer users' motivational needs when using computers and other devices (Jung, Schneider and Valacich, 2010; Zhang, 2008). Hence, affordances are perceived as being valuable and meaningful based on the observer's selective attention, which is in turn controlled by the observer's needs (Gibson, 1982). Motivational affordances are part of the intelligibility of practice as they help individuals respond to the goals of practice. Acting skilfully in the face of affordances, as Dreyfus and Kelly (2007, p. 52) noted, means that one is ‘immediately drawn to act a certain way’ in a given activity. Still, the skilful individual has the capacity to manipulate, modify or even manufacture (Gibson, 1979) affordances so he or she can intelligibly fit with planned or spontaneous actions within the realm of practice (Reed, 1996).

As already explained, ecological psychology speaks of objects in the broadest sense, including environmental, animate, edible and manufactured objects (Reed, 1996). However, I limit my discussion to manufactured objects, specifically tools, such as ‘frameworks, concepts, models, or methods’ (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014, p. 2), texts, i.e. ‘any discourse fixed by writing’ (Ricoeur, 1981, p. 145), and technologies, or technologies-in-practice, i.e. ‘the specific structure routinely enacted as we use the specific machine, technique, appliance, device, or gadget in recurrent ways in our everyday situated activities’ (Orlikowski, 2000, p. 408). Using these various manufactured objects interchangeably is important since objects have a complementary and co-evolutionary agency in practice. For example, a document template is produced through a computer (program), printed out on paper through a printer, filled out with a pen, its textual content re-entered into yet another computer program etc. This complementarity shows, through the doings (i.e. verbs), that material agency is conjoined with human agency and that each affordance is situated in a practice event while being contingent upon its past, present and anticipated future affordance events and is thereby bundled with other affordances in the chain of actions.

Given these features, the notion of affordances brings an opportunity to study what Chia and Holt (2006, p. 641) termed the ‘equipmental nexus of things’ and Faraj and Azad (2012, p. 239) called ‘bundles of features’. Analogous with these views, I consider affordances as ‘bundled action possibilities’. This distinction implies that objects have multiple affordances and, in contrast to Gibson, that the affordances of different objects may point to each other such that they are entangled in a nexus of action possibilities despite their ontological distinctiveness. I make this distinction to better illustrate how agency may take place without the physical presence of material objects. More specifically and related to strategy practice, I define bundled affordances as temporally and spatially distributed yet entangled action possibilities afforded by material and digital tools for the purpose of strategic ends. This definition further assumes that when an activity is carried out, agency is no longer purely social or exclusively material (Nyberg, 2009); it is a ‘co-performance’ of social and material agency (Pels, Hetherington and Vandenberghe, 2002).

In taking this perspective, the concept of affordances allows us to analyse the intricate entanglement of human–material agencies and theorize on the ‘complementarity’ (Gibson, 1979, p. 127) of strategy actors and their tools in strategic activity. Adapting the affordance lens to strategy work suggests that, although social and material features may exist apart from each other, their value comes from how they are enacted together in strategy practice. Hence, instead of focusing on the individual as the starting point of action, the concept of affordances allows us to start with action and understand how certain events are connected with others despite their spatial and temporal separation.

This view builds on and extends the understanding of strategic activity as interactions between individuals, their objects, and the particular cultural and historical contexts within which activity takes place (Jarzabkowski, 2003). However, instead of considering interactions with technologies as a basis for interpretation and meaning generation (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014), I treat such interactions as affordances for action with a ‘functional specificity’ (Reed, 1996) irrespective of the interpretive processes of the individual. Such a view positions strategic activity as one out of many bundled activities within practice. Activities are observable to others yet not fully comprehensible due to their tacit nature (Schatzki, 2010). Thus, activities are bundles of performances with specific spatiotemporally defined sites of action, comprising parts of a larger nexus of bundled activities within a given practice. In making these considerations, this study is guided by the following research question: how do strategy actors instil strategic behaviour in everyday strategic activity despite their physical absence?

Research site and methods

The present study builds on qualitative data generated from three affiliated Swedish banks: Alfabank, Betabank and Gammabank (all pseudonyms). The banks in the present study are autonomous organizations with their own local visions, goals and strategies, but they have in common a long conflated history dating back to 1820 as well as similar goals and missions. Therefore, they have a more or less identical set of practices for shaping, changing and delivering their products and services. Alfabank came about in 1992 when approximately 400 out of 498 small savings banks decided to merge to maintain their relative viability and respond to the increasing competition from larger banks. A few years later in 1997 Alfabank merged with another relatively small but nationwide bank in order to further strengthen its market position among private customers. However, Alfabank's cooperation with the other savings banks still remained and is today governed by agreements that regulate all the banks' activities and, to a large extent, the products and services they offer. Important to this study, though, is that Alfabank's role in this constellation is to provide the affiliated banks with an information technology (IT) infrastructure with nearly full access to documents; work guidelines; risk, credit, and customer-assessment tools; the bank's intranet; and service and support.

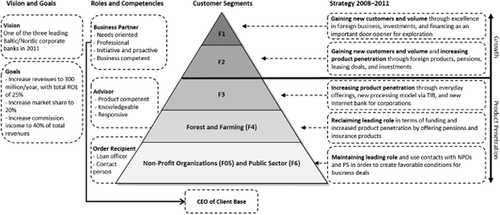

In 2007, however, a new strategy was implemented throughout the coalition aiming to increase market shares among large corporate customers, increase the product penetration ratio among small- and medium-sized firms, increase the number of satisfied customers, sell more commission-generating products/services, simplify internet-based banking services, and spend more time on individual customers (see Figure 1). Indeed, the banks' operational practices were upgraded to strategic practices and were considered important to the banks' strategic goals: ‘Corporate advisors are the most important actors in our new strategy, and everything they do has implications on our strategic goals in each market’ (field note, specialist, Alfabank).

Vision, strategy, goals and advisor roles and competences

Hence, the success of the new strategy was particularly critical for the corporate advisors (hereafter, advisors) who had to discard their prior roles as order recipients. Instead, they had to become ‘business partners’ and take full responsibility for planning and setting personal goals as well as for maintaining, leveraging and developing their own customer base. In short, the new strategy assumed an upgraded role for advisors, urging them to become the ‘CEOs’ of their customer base. Consequently, advisors were expected to be demand oriented, professional, proactive and business competent. Thus, strategic banking practice in this context is an inclusive term, refers to multiple levels of the organization that are bound to a specific set of material artefacts, and has a discourse of its own.

Methods

Consistent with prior research on the material agency of strategy practices (Kaplan, 2011; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010), my data collection comprised primary sources (e.g. ethnographic data, interviews, diaries) and secondary sources (e.g. internal documents, archival data, public sources). The goal of primary data collection techniques was to be able to understand the ‘tacit, inarticulate and often inarticulable understandings of strategy practitioners’ (Chia and Rasche, 2010, p. 36). I conducted 79 semi-structured interviews with 45 informants (see Table 1). All interviews were recorded and transcribed except for eight interviews. In those cases, careful notes were taken during the interviews and immediately converted into write-ups (Miles and Huberman, 1994). The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. Informants were chosen both selectively and through a snowball technique (Miles and Huberman, 1994). In both cases, informants had to be involved in either developing or implementing the new strategy, developing or implementing the technologies and material objects (e.g. instructions, guidelines etc.) for the new strategy, and actively realizing the new strategic goals. Over time, I had repeated discussions with 13 select informants to enrich my understanding of emergent topics and issues (Pettigrew, 1997).

| Alfabank, unit/branch | Betabank, unit | Gammabank, unit/branch | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HQ | A | B | C | D | HQ | HQ | A | Total | |

| Observations (hours) | 73 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 5 | 115 | |

| Interviews (n) | 41 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 79 |

| Board | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Top management | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| Specialists | 16 | 1 | 17 | ||||||

| Branch managers | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Advisors | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 13 | ||||

| Informants | 20 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 45 |

In addition to interviews, I also conducted both direct and participant observations of 22 meetings (110 hours in total), out of which 14 (73 hours) concerned the development of a business planning and development tool. I also made a final observation of a two-day (13 hours) training session in addition to more unstructured observations of everyday activities at branch offices during the interviews. All observations were voice recorded, selectively transcribed and documented through field notes.

The interviews were initially unstructured and discussion oriented, comprising a number of board members, managers and specialists. These interviews were combined with observations of meetings. The goal of both measures was to understand what sites these actors operated in, what roles they played in relation to the new strategy, how they implemented strategy, how various practices were interlinked throughout the organizations, what tools they used in practice and how they used them. This understanding was of particular importance as the implementation of the new strategy involved major adaptations of the banks' IT infrastructure and could have thus evoked divergent responses (Stensaker and Falkenberg, 2007) from the end users: ‘Alfabank's strategy is to expand into new geographic areas and new segments in existing markets. Investigating the generative mechanisms of business decisions related to the existing [IT] system structure is therefore important to us’ (top manager, Alfabank). In addition, the informants were keen on understanding the ways in which various tools and technologies were ‘enacted, changed, and maximized for strategic uses’ (top manager, Alfabank), making them particularly committed (Balogun, Huff and Johnson, 2003) to discussing their development and use in practice. Meeting observations also provided opportunities to test some of the technologies and talk to IT personnel about how they continuously worked to ‘adapt existing systems to general uses … and to make people adapt to the systems and to adopt better ways of using the technology’ (specialist, Alfabank).

Gradually, however, questions became more specific, and I asked them repeatedly to informants. Consistent with Zammuto et al.'s (2007) recommendations of being attentive to affordances of organizing, specifically those of visualizing entire work processes and enablers of various forms of collaboration, I asked questions such as ‘Can you describe your work?’ (with follow-up questions on the tools used for various tasks, activities or steps throughout a process), ‘Can you describe how your work connects with others' work (colleagues, manager, specialists etc.)?’ and ‘Can you describe what the bank's strategy implies for you in your everyday work?’ Hence, the questions (see Appendix S1) and their associated follow-up questions were directed toward capturing how activities are bundled and thereby augment organization members' ability to ‘respond to dynamics in the entire [work] process’ (Zammuto et al., 2007, p. 753) at a distance.

The collected data thereby help an understanding of (1) what activities informants engage in and how they carry them out; (2) how and from where they collect, handle and analyse information; (3) how they handle unexpected circumstances; and (4) how different objects (e.g. IT, documents, guidelines) constitute and are constituted by their practice. However, to illustrate these features of strategic activity, I intentionally leave out some intricate details relating to everyday work practices. It should also be clarified that the results presented here reflect Alfabank's efforts to instil strategic behaviour throughout its network of branch offices and affiliated banks. In this study, however, I have chosen to neglect the affiliated banks' local adaptations of Alfabank's strategic mission. Such adaptations were mainly performance measures and were thus not of significance for the present study.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out as an iterative back-and-forth process between theoretical concepts and empirical data. This abductive approach (Cornelissen, Mantere and Vaara, 2014; Klag and Langley, 2013) was particularly valuable as I could move between the data and the concept of affordances to elicit the entanglement of social and material agencies across sites and time in strategic activity and explore how affordances were bundled. Locating affordance bundles in practice events was important since ‘The information for an affordance is to be found in events that include the relevant environmental features, the activity of the organism, and the consequences that ensue as well as the relations among these’ (E. J. Gibson, 2000, p. 54).

As an initial step, however, I followed Miles and Huberman's (1994) recommendation of continuously analysing the data. On an ongoing basis, I analysed notes from the meetings between managers and specialists at the banks, the interview transcripts, and the archival material that had been provided to me to identify sources of affordances, their effects and their relationships. I made notes in my transcripts and continuously developed short narratives (Langley, 1999) about affordances, such as their occurrence in different organizational sites, levels and functions. This step helped me make a detailed mapping (Langley, 1999) of how key actors' actions instilled strategic behaviour across the banks and how affordances played out in different practice sites, including the various activities involved (see Table 2). However, for the purpose of clarification, it is worth noting that I ignored variance across the three banks and instead focused on common practice.

| Strategic activities | Market analysis | Segmentation and prioritization | Planning customer relationship | Preparing customer relationship | Meeting customer | Following up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Annually, monthly | Recurrently | Weekly | Recurrently | Recurrently | Recurrently |

| Purpose | Learning/negotiating | Negotiating/ intuiting | Intuiting/acting | Acting/reacting | Nourishing | Aligning |

| Material sitea | CAS, CAT, business data, UC, internal industry analyses, Datscha, SME barometer, spreadsheets | Business data, UC, My Customers, KBA, KRES, KPI lists, spreadsheets | Business plan, Folder 5 in CAS, KRES, spreadsheets | Business calculation, ROE, cash flow, Env. analysis, M&A analysis, BEAN, CAT, telephone, email, Outlook, notebooks | Placement guide, tenders in Word, customer plan, Interview Guide, CAS, CAT, documents, spreadsheets, notebooks | Scorecards, MUPP, My Customers, KRES, CAS, CAT, telephone, email, Outlook, spreadsheets, notebook |

|

Affordance function |

Motivating | Constraining | Constraining/controlling | Constraining | Motivating | Motivating/controlling |

| Empirical example | ‘Business planning implies an analysis of, among other things, the market, the customer base, and the credit portfolio. … The municipality list of incoming companies, the export and import register’ (Operations Manual) | ‘Prioritize sales to customers based on central/local market plans (or product level)’ (specialist, Alfabank) | ‘Make an action plan for how and when to meet the customers’ (Operations Manual) | ‘Make a meeting preparation form for new customers to be used before the meeting. Put it on the Web so that the customers can also prepare for the meeting’ (Advisors' Interview Guide) | ‘Package the “everyday” offer clearly and simply: this is what it means to become a corporate customer’ (Strategy Document, Alfabank) | ‘You are personally responsible for following up with the development of your customer portfolio based on your individual goals as stated in the scorecard’ (Operations Manual) |

| Link to ove rall strategy | Increasing customer base (customer segments F1 + F2) | Increasing product penetration and volume (all customer segments) | Becoming demand oriented and proactive | Becoming knowledgeable, professional, business competent | Becoming product competent, attentive to customer needs | Regaining and strengthening market positions, relationships with NPOs (non-profit organizations) |

- a Acronyms are used for proprietary technologies and tools to ensure the banks’ anonymity.

As a second step, I went back to the concept of affordances (Gibson, 1977) and practice theory (Schatzki, 2005) in order to enrich my understanding of the observed phenomena. Analogous with Schatzki's conception of practice activities as ‘distributed bundles’, I found that affordances followed the logic of practice as a nexus, or ‘an organized, open-ended spatial-temporal manifold of actions’ (Schatzki, 2005, p. 471). Inspired by this, I structured the affordances found in the data into three identifying properties: connectedness, spatial orientations and temporal orientations. These three properties formed the empirical basis of affordances as bundles – i.e. as multiple interconnected action possibilities that span spatial and temporal dimensions of strategy practice. Following this conception, I classified the affordances' generative properties: what affordances prompt actors to do (i.e. motivating, constraining and controlling strategic action), where they do it (i.e. their practice site and corresponding material site) and when affordances prompt strategic action. Consider, for example, this comment from a top manager at Gammabank: ‘To be able to make good plans, I automate or at least integrate some data into the CAT [customer analysis tool]. … For example, if I'd like to see those [customers] who increase their monthly income drastically for a certain period, those who make transfers to niche banks or invest in insurance solutions, those who are active in using credits, or those who have a fortune’ (top manager, Gammabank). This quote illustrates what the CAT (i.e. the material site) enables in terms of strategic planning (i.e. the practice site), and it reveals that the CAT offers multiple entangled action possibilities.

Based on this understanding of the concept of affordances, I edited the practice mapping and added the affordances identified in strategic activity as well as the functions they served in each instance (see Table 2).

As shown in Table 2, I mapped six key activities and located their respective strategy link, nexus of material artefacts and affordance functions. However, recalling the three guiding questions, I expanded the narratives such that I could capture the emergence of bundled affordances as well as their identifying and generative properties. For example, as part of their overall practice, advisors analyse the market, soliciting a whole nexus of objects (e.g. the CAT, the customer administration system [CAS], Excel spreadsheets) on an annual and monthly basis usually sitting in their office. The nexus of tools at hand is commonly of the motivational character, inspiring advisors to search and sort customers as they wish. However, the motivational character of these affordances cuts across time and space such that it orients the advisors' attention backward to the stated corporate and branch goals and forward to possible personal actions that can help them realize personal goals (stated in scorecards). I now elaborate on how bundled affordances instil strategic behaviour.

Findings

In this section I first present how affordance bundling was carried out as an important strategic initiative within the banks. Then, I provide two activity examples from the perspective of the advisors to illustrate how these affordance bundles prompted strategic behaviour at a distance.

Affordances as bundles

Following the implementation of the new strategy, a team of business developers and IT developers was formed with the goal of making amendments to the practice infrastructure (e.g. rules, guidelines, technologies) in order to instil strategic behaviour and achieve strategic goals. As one specialist at Alfabank put it (field note), ‘Implementing a new strategy isn't about introducing a system and hoping that they [the advisors] will change. We have to change the users' behaviours at the same time and make sure they change their mindset and attitude. But at the same time, we can't change the mindsets and attitudes without changing the systems and hope we can achieve a new way of working if there's no systems support in place. All these things need to go hand in hand.’

The group's mission was simply to control the entanglement of social and material agencies rather than relying on ‘hope’ when instilling strategic behaviour. This implied, among other measures, that ‘Existing information [on customer affairs] will be reused but highlighted with visual cues’, as stated in a strategy document. Indeed, the rationale was to leverage existing affordances that resided in familiar information stocks and familiar material interfaces by presenting them in an actionable, inviting manner.

As one specialist at Alfabank recognized from a field study among 20 branch offices, familiar information stocks included ‘average balance, utilization of overdraft, product penetration and usage, payment and transaction flows’, among other features. In practice, as he demonstrated during a strategy meeting, this information would ‘stand out’ and serve as ‘a strategic action possibility’ if the following equation could be visualized: ‘average [customer account] balance of X kr [SEK] = highlight investments [to customer]’. Hence, when analysing customers' various affairs in the CAT, ‘the advisor's attention will be drawn to the part of the computer screen where the customer's average account balance is presented when it exceeds a certain limit’ (specialist, Alfabank). Making this change would imply that the advisor is invited to take a strategic action – namely, to initiate the process of exploring opportunities for offering the customer a qualified proposition and investing money. Indeed, the group agreed that the CAT will ‘make it easier for advisors to select customers’ (specialist, Alfabank). Thus, in a subsequent strategy meeting, the participants agreed that ‘Advisors need to be helped in taking this important role of making the right strategic decisions’ (top manager, Betabank). Following this agreement to inscribe an invitational affordance into the CAT, several assisting affordances were bundled with this strategic initiative.

Over the next few months, changes were made in the CAT which resulted in, for example, a diagram that visually presents each customer's average account balance such that there could be ‘no hesitation that there's an opportunity to be captured here’ (specialist, Alfabank). Several features highlighted opportunities, including the position of the diagram (in the upper left-hand corner of the computer screen) and the colours of the graphs indicating the credit limit (green) over time and average balance (red) plotted over a 12-month period, among other affordances.

Upon trying out the new features of the CAT, one board member of Betabank noted, ‘The system becomes meat and blood. … It opens “millions of eyes” ’, indicating that the diagram and its assisting features invoked a sense of co-presence between one's own bodily dispositions of what to look for on the computer screen and where, including the whole lineage of occurrences from past events to future plans, anticipations and motivations. The board member, herself being a trained advisor, further clarified that ‘When one captures reality [customers' financial situations] in this dense format, it opens up a whole spectrum of opportunities for action honed in the past and the future at once’.

Meanwhile, changes were also made in several documents and guidelines. For example, an updated version of Alfabank's business concept document clearly described what the new strategy means for advisors, outlining that they must ‘Identify excess liquidity and investment needs’ as well as conduct meetings with an interview guide, among other things. The latter was in turn modified such that a new field was inserted in the interview guide asking, ‘Does the company have any money left?’, with two checkboxes (Yes, No) and other fields inviting the advisor to fill out ‘Buffer savings and placements’, ‘Now (today)’ and ‘Future’ as well as the distribution of the savings: ‘Alfabank/Affiliated bank’ and ‘Other bank’. This change in the interview guide invited advisors to act strategically in two ways. First, it served as a possibility to ‘establish a feeling for new customers' solvency and need for credits’ (advisor 1, Gammabank). Second, advisors were legitimized to ask customers about which banks they used for their business: ‘When we ask these questions, customers take it seriously and feel obliged to answer, and because we have a form to fill out, it is legitimate for us to ask those sensitive questions’ (advisor 3, Betabank). As noted, the interview guide created a shared commitment between the advisors using it and the customers answering the questions to act in a certain way, which in turn is a commitment – although at a distance – toward the strategy group and the overall corporate strategy.

In addition, when the advisors gathered this information, there was a corresponding ‘entry point’, a familiar source within the CAT where the information could be entered. In this way, the whole chain of actions prompted the advisors to become more ‘aware of the link between asking a question and actually contributing to the strategy by selling more, increasing the product penetration ratio’ (top manager, Gammabank). This action process was further extended by integrating the CAT with the advisors' individual scorecards where their performance rate in terms of selling an investment based on indications from the diagram was summarized under the product penetration ratio section. As clarified during a field visit, ‘Good behaviour is promoted in this way. … They [the advisors] will see that finding ways to realize our strategy is personally beneficial’ (branch manager, Alfabank Branch A).

However, as part of this ongoing bundling of affordances for material artefacts, Alfabank and its affiliated banks started network sharing among advisors at the regional level in order to instil strategic behaviour among the advisors. More specifically, this network sharing was aimed at helping the advisors become more attentive and responsive to products and services that were high on the strategic agenda and helping them deal with opportunities: ‘Since the new strategy was rolled out, we have gained many new advisors, and they all need to know how to handle the “hot list” [prioritized customer segments and objectives] as it requires that they're focused and diligent. Many of our new advisors don't know the profit levels of our products or services and that they should give priority to the best deals and let others take a little longer turnaround time’ (branch manager, Alfabank Branch C).

At the branch level, branch managers were given a new role that qualified them to serve as ‘strategy agents’. These branch managers were instructed to support the advisors in setting annual plans for realizing their share of the corporate strategy on a yearly basis. The strategic plans would then be reviewed and compared with the individual scorecards on an annual basis and selectively on a monthly basis. The business concept document again instructed branch managers and advisors to hold ‘Sales support meetings … at least once per month’. These meetings centred on the scorecards, but the scorecards and other measures received their meaning and value from the socialization around them. This is how one branch manager (Alfabank Branch B) described the content of monthly meetings with advisors: ‘What have I promised to do? How far have I reached? Why did this work out, and why not? What do I do in the next step? Everyone is aware of what others are doing. That's how we get completely different individuals into a homogeneous group and can support and help each other. That's what we really do to make sure that we're aligned with the strategy on a monthly basis.’

In sum, specialists and managers at Alfabank and their affiliated banks worked out the new strategy such that various strategic goals were addressed through the inscription of affordances in an array of practice domains, pairing social behaviours and material artefacts and tools. In doing so, the social and material dimensions of practice were entangled through affordances aimed at realizing strategic goals. For example, when the business concept document was updated according to the new strategy, a new section was introduced with hyperlinks to supporting documents and tools (e.g. the interview guide, the goal and strategy document, and the scorecards for corporate advisors). In this way, affordances were established in a non-sequential nexus (i.e. they all pointed toward each other) and in a non-hierarchical structure, but they helped point Alfabank's entire corporate business organization and the affiliated banks toward the stated strategic goals. As one specialist at Alfabank said, ‘we've put quite a lot of work in the business planning material; we've constantly improved it pedagogically, visualized the strategy, what it is that we mean by this [the strategy], what it does de facto, and how advisors should use it’. However, as described above, the affordances had different functions in this non-sequential nexus. I now show the ways in which these affordances prompted strategic action among the advisors.

Affordances for strategic action

In order to realize the corporate strategy, the advisors were bound to make a strategic activity plan for their everyday work. However, as part of designing bundles of affordances that instil strategic behaviour, the plan was edited and expanded from three strategic activities (i.e. analysing the market, segmenting the market, and following up with customer meetings) into six activities, as shown in Table 2. For the sake of parsimony, I focus on the first two activities.

Analysing the market

Analysing the market was a precondition for maintaining focus on the strategic targets set for 2008–2011. The advisors were expected to ‘scan the market’ every month to make sure they were ‘alert to increasing the customer base’ (branch manager, Alfabank Branch C). According to the operations manual, the advisors were offered multiple opportunities to analyse the market: ‘The below described annual planning document is intended as inspiration in your work. There are several ways to make a good annual planning, among other things digitally [Excel] or on hard-copy.’ In action, however, the advisors often spoke of this activity in motivational terms and in terms of fulfilling personal goals: ‘I try to find companies that match my area of expertise and, of course, I search for companies that I think are fun to work with’ (advisor 3, Betabank).

Thus, because the CAT was configured to provide multiple action possibilities, the advisors were motivated rather than constrained to produce subjective facts about the market through embodied sensing mechanisms, which became materially inscribed as objective facts: ‘First, you put all the information you have on your mind in the system [CAT], and then you pick the same info from the same system just to move it over to a spreadsheet’ (advisor 2, Gammabank). Another advisor from Betabank said, ‘my market segment is really my backyard. … I'm myself a farmer, and I know the industry pretty well, and I'm also trained as a land surveyor.’ As indicated here, the advisors were inclined not only to blend their subjectivity in their analyses but also to render the outcome (i.e. the hot list) more valuable and meaningful in their practice.

In summary, affordances emanating from market analysis activities had a motivational character and expressed the material properties of the CAT and other tools. These were in turn entangled with the advisors' preferences, moods and emotional relationships with their ‘market’. Thus, strategic activities continuously emerged through this seamless coalescence of social and material activity. The advisors often brought up the issue of being personally engaged in the plans to the extent that the plans themselves – as artefacts – became inseparable from everyday work. They were simply incorporated in the body: ‘One simply feels what needs to be done next’, as one advisor at Gammabank told a colleague during a work observation session.

Segmenting and prioritizing customers

Because the advisors had a certain degree of freedom in analysing the market, the hot list had already limited the variance of affordances for segmenting and prioritizing the market. Unlike the previous activity, the advisors were constrained to extract a so-called hot list based on a limited variety of customer segments (e.g. F1, F2, F3), the advisors' specific area of expertise (e.g. properties, start-ups), skills (e.g. key ratio analyses) and personal preferences and goals. For example, one advisor (advisor 3, Alfabank Branch B) noted: ‘My main interest is to see how much I can earn on each customer. That's one way to quickly find relevant customers. … The most significant variables are earnings margins. … Such things give you a quick signal on the decision authority for each customer.’

Furthermore, as noted above, just like analysing the market, segmenting and prioritizing customers was connected to other related activities, in this case decision making. Indeed, this orientation toward short-term gains was geared toward augmenting individual motivations; it had an inviting character to maximize prospects in the hot list. This was afforded by the individual scorecard, which was virtually bundled with all practice activities as it served as a background against which advisors measured the strategic value and meaning of their activities. Because the individual goals, the analysis, and the segmentation and prioritization of customers constituted one another, there was an intricate bundle of affordances present across all activities that pointed attention and action toward one's personal goals and those of the organization. This is how one advisor (advisor 1, Alfabank Branch B) expressed this notion during a field visit: ‘I felt that I shouldn't look for those customers with super high turnover, so I checked a little lower. I searched for customers whose turnover didn't exceed 30 million, and I also searched for those with high solidity ratios. … I felt it was okay to start at a lower level and work my way up. Then, on the other hand, it might be good to look for companies with many employees or firms in a specific branch or so.’

As noted above, the advisors balanced their segmentation and prioritization criteria at three levels: the personal skill level, the level of risk that can be taken with a certain customer or segment, and the predefined corporate-wide customer segmentations. Because there was an inherent constraint in this activity, some advisors noted that there was a ‘closure effect’ in the hot list. It tended to narrow down the scope of further segmentation and prioritization activity. As expressed by a former advisor at Betabank, ‘the list is the market’ and becomes subject to ‘re-ordering and reshuffling until nothing more is left’.

Discussion

In an attempt to advance our knowledge of material agency in strategizing, the present study aims to frame strategic activity as a spatiotemporally separate and separable bundle of subject–object solicitations. To this aim, material gleaned from three affiliated banks is used to analyse how strategy actors instil strategic behaviour despite their physical absence in everyday strategic activity. Identifying this phenomenon and articulating the underlying generative mechanisms offers a number of insights into the literature on material agency in relation to strategizing and strategy practice.

Entangling affordances into bundles

Prior studies have acknowledged the importance of studying the mutual constitution of the social and material – notably, textual agency – for advancing the prevalent understanding that strategizing is a social accomplishment (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Kaplan, 2011; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010). The present study contributes to this body of literature by showing that strategists at various levels of the banks instilled strategic behaviour through the active control and design of documents, tools and technologies such that they prompted strategic behaviour that contributed to the realization of corporate- and branch-level strategic goals. However, in order to instigate strategic behaviour among peers, the strategists took advantage of advisors' familiarity with information stocks and existing tools and redesigned them to augment their potential affordances in line with the stated strategic goals. Specifically, management and specialists brought to the fore familiar information stocks by making them visually perceptible to advisors and by arranging them according to common praxis among advisors. However, familiarity with and the visibility of information alone does not yield a change in behaviour unless the informational stock is recombined in ways that prompt responses to strategic opportunities (Zammuto et al., 2007). Thus, in its renewed shape, customer information enabled advisors to ‘deal with old opportunities in new ways’ (manager, Gammabank) and to reduce the likelihood of other possible action opportunities arising from various strategic events to compete with the new affordance bundle.

Indeed, while previous research has shown how this ‘self-authorizing’ characteristic of strategy texts prompts strategists to ignore other ‘non-strategic’ tasks (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010), the present study shows how the entanglement of tools-in-use can in fact render the rationality of everyday tools (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014) more strategic, thereby aligning the whole nexus of everyday practice activities with stated strategic aspirations. Drawing on the concept of bundled affordances, the results show how such effective entanglement of affordances not only can help discipline certain command structures (Mantere and Vaara, 2008), subsequent decision making (Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010) and communication (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011) but can also help control a whole chain of actions consistent with strategic ends.

Motivation as a source of re-bundling of affordances

The results further show that controlling contingently unfolding strategic action opportunities is facilitated by motivational affordances. As illustrated earlier, motivational affordances persisted when advisors were afforded ways of acting legitimately toward customers and of aligning strategic behaviour with individual performance metrics. Hence, this way of bundling affordances secured advisors' liability to repeat strategic behaviour and commit to top management, strategic goals and the continued use of tools. Entangling familiar information stocks with other affordance bundles that prompt strategic behaviour dovetails with Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli's (2010) study asserting that unfamiliar terminology distracts strategists from strategizing unless they are given ‘a great deal of explanations and definitions’ (Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010, p. 692).

However, from the perspective of bundled affordances, explanations and definitions need to fall within strategists' attentional scope as well as motivate strategists to intuitively act upon them as inextricably entangled with their associated terminology-in-use. The present study illustrates this concept by showing how the affordance of analysing the market and that of structuring it coexisted seamlessly in one and the same activity such that they operated as mutually constitutive processes (e.g. responding to personal goals, corporate strategy, branch-level goals etc.). Neurological accounts of affordances have recently confirmed this co-performance of affordances by showing that, during interactive behaviour, individuals typically resolve the affordance competition problem (i.e. deciding and planning actions) by putting multiple affordances in operation simultaneously (Cisek and Kalaska, 2010). Moreover, individuals' motivations can alter or reconfigure co-performing affordances into any novel bundle depending on whether, when and how subject–object co-performances occur. Therefore, when bundles of technological features – being either mutually reciprocal or constitutive of one another, as these findings illustrate – co-present in action, they come forth not as technological properties but as bundles of capabilities (Faraj and Azad, 2012).

Transcending spatiotemporal affordance boundaries

Whereas discursive accounts of strategy practice have assumed the value of information in communication and strategy texts, I propose here that affordances reside in practice events as human activity becomes intelligible and meaningful through practice (Schatzki, 2005). This is the reason why, once the advisors started segmenting and prioritizing customers, they experienced a closure effect in the hot list – a material propensity to bring forth a valuable set of customers that meant something for each of them as they took into account the historicity of practice and the contextual demands put on them as they strived to realize their strategic goals. This peculiarity of the hot list is granted strategic status because the practice event is emphasized rather than the information it offers for interpretation and sensemaking by the advisors.

From an ecological psychological perspective, E. J. Gibson (2000, p. 53) argued that, ‘Because perception is prospective and goes on over time, the information for affordances is in events, both external and within the perceiver’. However, in contrast to some previous studies (Kaplan, 2011; Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli, 2010), the present study shows that documents and tools do not superimpose present agency on future decisions and choices. Rather, the concept of bundled affordances, specifically their familiarity and perceptibility, helped advisors more easily draw on past affordances and entangle them with present affordances and thereby anticipate future action possibilities. Thus, viewed through the lens of bundled affordances, multiple affordances present themselves as one unified nexus of affordances that spans spatiotemporal boundaries. This allows us to consider the analytical value of strategic events as opportunities to identify how the spatiotemporal boundaries of affordances are transcended. Instead of affordances being open-ended action possibilities with flexibly variable meanings and values, bundled affordances prompt skilled actors to act in a strategically purposeful and engaged manner owing to their capacity to join past actions with present opportunities as well as to anticipate the future and the resulting effects of their actions. As one manager said, ‘It is also about intuiting which customers could bring you that little extra thing’ (manager, Betabank). Strategic activity from this view is thus not an open-ended activity with vague meaning and value. When viewed through the lens of bundled affordances, strategic activity appears as a novel, purposeful and meaningful arrangement of affordances emanating from various practice sites that converge and co-act as one specific action opportunity.

Bundled affordances as invariant information

It is commonly held that strategy texts are liable to flexible interpretations by strategists (e.g. Giraudeau, 2008; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011). For example, Vaara, Sorsa and Pälli (2010, p. 694) explained that after several amendments ‘the strategy text also led to other kinds of interpretations’. From an ecological psychological approach, however, action possibilities are not contingent upon the interpretive viability of individuals but upon their ability to perceive invariant information in their environment (Gibson, 1979). To be clear, Gibson argued that such information is often too rich to be processed according to the stimuli–response models of communication, offering an alternative that views the affordances of things as ‘perceived directly’. The concept of affordances, therefore, flips the interpretivist view of information processing by suggesting that information pickup is about detection rather than construction (as implied in the notion of interpretation) and that ‘the observer's job is not to create information but to find it’ (Reed, 1996, p. 65, original emphases). It is noteworthy, though, that such mundane strategy tools as PowerPoint documents have been described as ‘the terrain upon which battles of different interpretations and interests [have] played out in the organization’ (Kaplan, 2011, p. 342). Similarly, strategy texts have been portrayed as being contingent upon the cognitive processing of objects' directly perceptible properties rather than their action possibilities. For example, Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011, p. 1231) explained that when strategists recontextualize a strategy text its meaning is ‘altered to better reflect academic values’. Whereas this recontextualization is indeed a possible agential amendment to texts, just as it is with most tools and technologies, it fails to explain the calls for action strategists are beckoned to respond to.

On this account, strategy texts are subject to interpretation and sensemaking by actors before they gain meaning and value. The concept of affordances goes beyond the logic of sensemaking, which has recently served to explain how strategic responses to organizational coordination come about (Cornelissen, Mantere and Vaara, 2014) and how middle managers enact sensemaking to discursively accomplish their strategic roles (Rouleau and Balogun, 2011). Whereas sensemaking (Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld, 2005) is often portrayed as a process of deliberation over the past and the future that is enabled by human agency, affordances (as portrayed here) are opportunities to capture spatiotemporally distributed action possibilities; they are concrete more than abstract and are enabled by the co-performance of social and material agency. However, both sensemaking and affordances serve as organizing mechanisms, although the organizing character of sensemaking occurs after the fact (Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld, 2005) and affordances are event driven and occur during action itself. From this perspective, bundled affordances are online events, appearing once individuals engage in a common and shared strategy practice. For example, an actor can see an opportunity for action (i.e. an affordance) if the figures in a market report are in accord with his or her plans and experiences. Similarly, when an actor engages corporeally with a new technology, he or she might sense an opportunity for action, be it incorporating the new technology into a new or pre-existing practice, avoiding it, or manipulating it so it fits with the nexus of activities within strategy practice. Thus, seeing and sensing relate to the affordances of texts, tools, technologies etc., not to their material properties or qualities (Gibson, 1979) as has recently been assumed in textual accounts of strategizing (e.g. Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011).

Concluding remarks

In pursuit of understanding strategic activity as a spatiotemporally separate and separable bundle of subject–object solicitations, I have introduced and extended the notion of affordances as the action possibilities and constraints prompted in subject–object encounters (Gibson, 1979). I have argued that affordances appear in bundles – namely, multiple and sometimes conflicting action possibilities within ongoing strategic activity. More specifically, I have empirically illustrated that bundled affordances present themselves conjointly within strategic activity and prompt strategic behaviour that spans temporal and spatial constraints. Affordance bundles bring forth action possibilities that are honed in past events, are contextually embedded in present opportunities for action and have anticipative power over future opportunities for action. Moreover, they locate action possibilities in displaced spatial locations in embodied activity, hence highlighting the relevance of temporal and spatial proximity to action possibilities.

This approach shows that affordances are effectively bundled when using familiar features of material objects and placing them in the everyday perceptual field of strategists. The study further suggests that when corporate interests and individual goals are effectively entangled into affordance bundles, they not only motivate individuals to behave strategically but also make those actions intuitive rather than open-ended action possibilities, instructive rather than interpretive, and readily identifiable in events rather than in information about the properties of objects (e.g. texts) and the fabric out of which material objects are manufactured. To these ends, the concept of affordances, specifically bundled affordances, provides an alternative lens for understanding the decisions, choices and solicitations of strategy objects for skilled strategy actors as they engage in everyday strategic activity.

Indeed the notion of bundled affordances also opens up new avenues for future research. For example, it provides a conceptual starting point for studying sociomaterial agency in strategy processes that stretch over time and space (Langley et al., 2013) and are conducted in complex organizational and environmental contexts (Denis, Langley and Rouleau, 2007). In particular, advocates of the discursive or communicative view of strategizing might find the concept appealing as bundled affordances have the capacity to capture multiple co-performing human and material agencies as they take place in increasingly digitized forms, such as chat rooms and social media. In addition, the approach proposed here is also promising for understanding the generative forms of ‘open strategizing’ as recently advocated by Whittington and colleagues (Whittington, Cailluet and Yakis-Douglas, 2011). Given that the concept of bundled affordances can expand and provide some explanatory power to these areas, such attempts would also serve as opportunities to refine the concept further.

Biography

Robert Demir is a post-doctoral researcher at The Ratio Institute. He received his PhD from Stockholm University School of Business. Robert is currently studying network strategizing. His research has appeared in outlets such as Qualitative Research, International Business Review, Critical Perspectives on International Business and Asian Business and Management.