The experiences of older adults with cognitive impairment in using falls prevention alarms in hospital: A qualitative descriptive study

Funding information: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abstract

Introduction

Bed and chair sensor alarms are commonly used for falls prevention in hospitals, despite questionable efficacy. Research analysing older adults' experiences of alarms is scarce, and adults with cognitive impairment are consistently excluded.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore how older adults with cognitive impairment perceive and experience falls prevention alarms in hospital.

Method

A qualitative descriptive design investigated older adults' experiences of alarms in a Geriatric Evaluation and Management ward in Melbourne. Patients were included if they had been provided an alarm. Semi-structured interviews were the primary method of data collection with two observation sessions and medical record analyses completed to enable triangulation of findings. Data were subjected to thematic analysis, and the Person-Environment-Occupation framework was chosen to add insight into the complexities of older adults' experiences of alarms.

Findings

All 11 participants had a level of cognitive impairment with delirium, confusion, or impulsiveness recorded in their medical file. Two overarching themes were identified: communication and collaboration with staff and rationalisation of alarm use. Participants' perceived staff were focussed on falls prevention but experienced a lack of communication about the purpose of alarms. Participants wanted an individualised approach to alarms. Some were comforted with the thought of alarms alerting staff, making them feel well cared for and believed alarms were a useful ‘back-up’. Others found alarms uncomfortable, frustrating, and restricting. Application of the Person-Environment-Occupation framework provided insight into how enabling and restrictive factors can impact whether the alarm is experienced positively or negatively. Seven unwitnessed falls occurred during the participants' admissions. Thirty-four per cent of alarm triggers observed were considered false alerts.

Conclusion

Older adults commonly reported negative experiences using bed/chair sensor alarms. Occupational therapists have the training to collaborate with people with cognitive impairment and assess the usefulness of alarms in reducing falls, based on how they interact with the older adult's unique person, environment, and occupation domains.

Key Points for Occupational Therapy

- Older adults with cognitive impairment want to be involved in decisions about falls prevention alarms.

- If an alarm is used, it must be individualised to the older adult's needs and preferences.

- The Person-Environment-Occupation framework adds insight into the complexity of older adult's experiences of alarms.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hospital falls can result in injury, death, increased length of stay, functional decline, and premature transition into residential aged care (Department of Health & Human Services, 2015). Falls prevention is an important component of occupational therapy practice in hospitals. Occupational therapists, physiotherapists, doctors, and nurses may recommend sensor alarms as part of a falls prevention plan when a person requires assistance to walk but cannot reliably request assistance via the nurse call bell. These alarms are pressure sensitive devices, placed on beds or chairs, designed to signal when a person attempts to mobilise so staff can attend. No clear criteria of who benefits from alarms exist. However, hospital post-fall checklists regularly question if an alarm was present, implying the lack of an alarm may have contributed to the fall (Schoen et al., 2016). Emerging opinions are that alarms could potentially contribute harm by increasing distress and sleep disturbance, hence the need to investigate the place for alarms in falls prevention (Oliver, 2018).

Alarms comprised the largest allocation of resources for an intervention aimed specifically at hospital falls prevention, an estimated AU$909 per bed per year (Mitchell et al., 2018). Yet growing evidence suggests that alarms are unlikely to prevent falls. A systematic review of three randomised control trials consisting of 29,691 patients showed a 19% increase in falls among patients using alarms (Cortés et al., 2021). In contrast, other studies indicate more technologically advanced alarms may reduce falls. For example, beds with inbuilt alarm systems that detect people sitting to lying, sitting on the edge of the bed, or standing have been shown to reduce falls (Seow et al., 2021). Most research has not purposively sampled those with cognitive impairment, except a small study, which revealed alarms were associated with a significant reduction in falls (Wong Shee et al., 2014). Hospitals are following the lead of some residential aged care facilities, who have removed alarms due to uncertainty surrounding their effectiveness (Crogan & Dupler, 2014), with a large randomised hospital disinvestment trial currently underway (Haines et al., 2021).

Hospital staff have expressed different perspectives on the usefulness of alarms for patients and themselves. Some nurses found them useful in reducing their workload (Subermaniam et al., 2017), whereas others found alarms added to the list of tasks they must attend to on the ward. Some nurses believe alarms are prone to technical problems and can be overused, noisy, and agitating to people, subsequently increasing their falls risk. Concerns exist that people not using alarms may miss out on nursing care due to the time spent answering alarms (Barker et al., 2017; Considine et al., 2023; Hubbartt et al., 2011; Timmons et al., 2019).

A systematic review found that patients are inactive or in bed between 87% and 100% of the day (Fazio et al., 2020). The impact alarms have on people's activity levels is unknown. Older adults may want to be active in hospital, and when unable to engage in meaningful activities, they could experience feelings of passivity, boredom, and disruption to their roles and identity (Clarke et al., 2018). Recently graduated nurses have expressed that alarms may act as a behavioural restraint (Okumoto et al., 2020). A restraint is any practice or intervention that has the effect of restricting one's rights or freedom of movement (Department of Health, 2022). It could be argued that if a person is scared or embarrassed to move in fear of activating the alarm, it may be considered a restraint. Research investigating the perspectives of those without cognitive impairment revealed that some considered alarms reassuring and a reminder not to walk unassisted, whereas others believed alarms contributed to immobility and felt embarrassed if the alarm activated unintentionally (Radecki et al., 2018; Timmons et al., 2019). Occupational therapists, among other healthcare professionals, must negotiate the tension of enabling the dignity of participation and freedom of mobility, in the context of managing high falls risk.

Occupational therapists can use a person centred approach to identify what enablers and barriers exist in hospital to achieve older adults' goals of meaningful engagement. Person centred care ensures that the person is placed at the centre of their care, has control over their care, and is an active participant whose values are respected (Nilsson et al., 2018). Kitwood (1997, cited in Brooker, 2016) suggested that many of the problems experienced in caring for people with cognitive impairment are interpersonal. They occur in the communication. He suggested we need to view the relationships between ‘carers’ and ‘cared-for’ as a psychotherapeutic relationship and, in this respect just as in psychotherapeutic work, the helpers need to be aware of their own issues around caring for others (Kitwood, 1997, as cited in Brooker, 2016). In contemporary clinical practice with staff performing time pressured, tasked focussed routines, it is unclear how often older adults' views are actively sought and considered when providing alarms.

Despite alarms forming a standard component of hospital falls prevention for older adults with cognitive impairment, their experiences of using alarms are not represented in the research literature. This is in contrast to the multiple publications exploring nurses' experiences of alarms. Given the uncertainty regarding the efficacy of alarms and their potential barrier to participation, older adults' experiences of using alarms must be sought and understood, to guide any subsequent recommendations regarding their future use.

The aim of this study was to explore how older adults with cognitive impairment perceive and experience falls prevention alarms in hospital.

2 METHODS

2.1 Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was received from both Eastern Health (HREC/79291/EH-2021-284152) and Flinders University (HREC CIA 5005-1).

Written consent was obtained from all participants or their proxy. Participants were reminded of the purpose of the research at each interaction (recruitment, observations, and interview) and ongoing assent obtained. All data were de-identified and stored on a password protected computer network.

2.2 Design

A qualitative descriptive study design was used because little is known about older adults' experiences of alarms, particularly those with cognitive impairment. A qualitative descriptive design incorporates various data collection approaches, uses purposive sampling to select participants with experiences of the phenomenon under investigation (alarms), and recognises the subjective nature of these experiences. Analyses stay close to the participants' experiences, involving a low level of interpretation, but allows space for the researcher to utilise relevant frameworks to guide analysis (Doyle et al., 2020).

2.3 Participants and setting

A purposive sample of older adults was recruited from a 22-bed Geriatric Evaluation and Management (GEM) ward within a large metropolitan health service in Melbourne where alarms were part of usual care. The ward had access to alarms that were regularly issued to adults deemed a high fall risk.

Inclusion criteria were older adults admitted to the ward who had been provided an alarm. Those with cognitive or sensory impairments or from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds were included.

Recruitment occurred between February and April 2022. Potential participants were approached in person for consent. All people using an alarm were invited to participate. Participants assessed as having a cognitive impairment (documented as a score of ≥4 on the Assessment Test for Delirium and Cognitive Impairment in their medical file) were provided with a simplified version of the participant information sheet, and their proxy was approached for formal consent via telephone or in person.

2.4 Data collection

2.4.1 Interviews

The researcher conducted all semi-structured interviews guided by an interview schedule (Table 1). Questions were asked specifically about alarms and general falls prevention plans to ascertain participants' thoughts about alarms as a falls prevention strategy. The interview guide was based on previous research on adults' perspectives of hospital falls prevention strategies (Radecki et al., 2018) and alarms specifically (Timmons et al., 2019). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

| 1 |

Are you aware that you are using a bed-chair sensor alarm? - Prompt: Explain that a bed-chair sensor alarm is a device placed on the bed or chair that senses movement - Prompt: Physically point to bed-chair sensor alarm |

| 2 | Can you tell me why you may require a bed-chair sensor alarm? |

| 3 | Can you tell me how you think the bed-chair sensor alarm works? |

| 4 | Do you have any thoughts or feelings on the usefulness of the bed-chair sensor alarm to keep you from falling? |

| 5 | How do you feel about using a bed-chair sensor alarm? |

| 6 | Is there anything about the bed-chair sensor alarm that you like? |

| 7 | Is there anything about the bed-chair sensor alarm that you don't like? |

| 8 |

Can you tell me about any plans discussed with you to reduce your risk of falling while in hospital? - Do you feel like you and your care staff share the same falls prevention plan? |

| 9 | Is there anything you would like to tell me that you do yourself to reduce your risk of falling while in hospital? |

| 10 | Is there anything else you would like to share with me about your experiences of using the bed-chair sensor alarm or what you think of them? |

It was anticipated participants, by virtue of being provided an alarm, were likely to have some level of cognitive impairment. FOCUSED (F, face to face; O, orientation; C, continuity; U, unsticking; S, structure; E, exchange; and D, direct), a known strategy to effectively interview adults with cognitive impairment, was adopted (Samsi & Manthorpe, 2020). Interviews were conversational, emphasising there were no right or wrong answers.

Interviews ranged in duration from 6 to 22 min. Three participants accepted the offer of member checking their transcript; no alterations were requested.

2.4.2 Observation sessions

Observation sessions complemented data gained through interviews, as it was acknowledged interviews may derive insufficient data due to cognitive impairment and difficulty verbally expressing experiences. Two overt, structured observation sessions, lasting approximately 60 min each, were conducted with each participant to provide a small snapshot of their alarm experience. Observations were conducted in the participants' rooms. There was one morning and one afternoon/evening observation for each participant to ensure the widest range of observational consistency, as participants may have presented differently throughout the day.

A coding sheet (based on that used by Timmons et al., 2019) and field notes were utilised to record: the location and position of the participant, any falls minimisation strategies used, responses if/when the alarm was activated, general activity or interactions, who was present and what was seen or heard.

2.4.3 Content analysis of medical records

Content analysis of medical records followed observations and interviews. Evidence of why and how alarms were used was reviewed, including documented participant reactions to alarms. The date range of medical record analysis started from the day of alarm prescription and ended 14 days later, or until discharge (whatever came first). A coding sheet was used to record participant characteristics including diagnosis, prior falls, in-patient falls, mobility status, and Functional Independence Measure (FIM) ratings. FIM ratings represent the need for assistance to complete daily tasks, with lower scores representing more functional deficits (Granger & Hamilton, 1992).

2.5 Data analysis

Familiarisation with data occurred through manual transcription of interviews and summarising observation and medical record analyses into word document tables. Data from interviews, observations, and medical records were analysed separately but then entered into a tabulated word document to enable data triangulation. This allowed findings from each method to be corroborated.

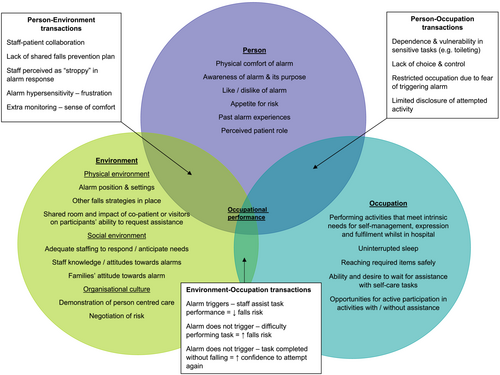

Data were explored within the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) framework (Law et al., 1996) to offer insights into how individuals experienced alarms. A two-step process was followed to apply this framework to participants' experiences of using alarms. First, important factors relating to the person, environment, and occupation, as they pertain to alarm experience, were identified. Second, the transactions between these domains were identified and their potential enabling or constraining effect on occupational performance.

Data were also subjected to thematic coding using constant comparison methods (Gibbs, 2007). Codes were initially data driven descriptive codes. Next, through moving backwards and forwards between the codes and data, similarities and differences were identified and categories developed. Finally, discovering common threads across categories allowed generation of overall themes. Regular meetings were conducted between researchers to establish consensus of overall theme construction. Example data and their respective codes, categories, and themes are shown in table 2.

| Data | Code | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘They keep reminding me, they say “I don't want you to fall,” that's all’. (P4) | Staff emphasis on avoiding falls but no detailed plan | Clarity of communication regarding falls prevention plan | Communication and collaboration with staff |

| ‘There is certainly nothing good about the belt, a leather belt just put underneath you. Well, I didn't know what the hell it was’. (P2) | Aware but not informed of why alarm used | Awareness of using an alarm | |

| ‘Because they think I might walk and might slip’. (P5) | Aware of falls risk | Awareness of why an alarm is required | |

| ‘You see I'm rather thin. And so it doesn't take much for something to stick in’. (P5) | Physical discomfort | Alarms are frustrating, irritating and restricting | Rationalisation of alarm use – Is it worth it? |

| ‘If you move a little bit, you bring in a nurse and she is turning off all the buzzes. That's quite a lot, all through the night’. (P1) | False alarms | Alarms not always working as intended | |

| ‘Well they're probably not a bad idea … extra back up in case someone does fall’. (P11) | Extra monitoring | Perceived usefulness of alarms in falls prevention | |

| ‘Every time I go to the toilet, I touch the … gestures pressing buzzer with hand’. (P6) | Calls for assistance when mobilising | Participant led falls prevention not involving alarms |

2.6 Rigour

Selection bias was minimised by inviting all adults using falls alarms on the ward to participate. Printed transcripts were offered to those who expressed interest to review their transcript to optimise validity. They were asked to record any desired changes via pen on the sheet for collection by the researcher. One researcher (K. S.) completed all data collection. Prolonged engagement fostered a familiarity and understanding of the context surrounding participants using alarms. This enabled reflexivity as the researcher could determine if they were being a source of bias by inadvertently altering the way participants may behave. During observation sessions, the researcher sat as far away as possible to limit interactions and used detailed structured observation field notes at the time of observations to limit bias in what was observed and recorded. Observations took place before the interview and medical record analysis with no pre-existing relationship or personal information known to potentially bias observations.

Confirmability was maximised by regular meetings between the researchers. A. C. was independent to the hospital organisation and experienced in engaging older adults with cognitive impairment in conversational interviewing to facilitate their participation in research. K. S. is an occupational therapist of over 20 years' experience, who frequently engages with older adults with cognitive impairment, gaining their consent to both interview and observe them, as part of their clinical role. With guidance from A. C., K. S. adapted these skills to a research context. Decisions regarding the way data were collected, analysed, and reported were decided between both researchers, to better ensure results were reflective of participants' experiences. Although an employee of the hospital organisation, K. S. held no pre-existing relationships with staff or patients nor input into ward activities. Neither researchers held a definitive position on the effectiveness of alarms, beyond acknowledgement that there were multiple pros and cons associated with their use.

3 FINDINGS

3.1 Demographics

Eleven older adults consented to participate (61% acceptance rate). The age range was 71 to 93 years. One participant (P3) was from a CALD background and required an interpreter. Another (P6) had aphasia and had their daughter present for the interview to assist with complex communication needs. Four participants sustained a fall (seven unwitnessed falls in total) during their admission. All participants had a primary diagnosis of a fall, confusion, delirium, or stroke. Additional demographic characteristics are shown in Table 3.

| Participant number | Age | Gender | Diagnosis | FIM admission cognition sub-score (35 = optimal performance) | Reported past history of falls in last 12 months | Inpatient fall during this admission | Mobility status when alarm prescribed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | Female | Gastroenteritis, confusion | 25 | Multiple | 0 | 1–2 person assist four wheeled frame |

| 2 | 82 | Female | Fall—cervical fracture, postural hypotension | 20 | Multiple | 0 | Supervision walking stick |

| 3 | 84 | Male | Evacuation of subdural haematoma*CALD | 10 | Multiple | 1 unwitnessed | 1 person assist four wheeled frame |

| 4 | 77 | Male | Fall, delirium | 17 | Multiple | 1 unwitnessed |

2 person assist mechanical standing aid Non ambulant |

|

5 |

91 |

Female |

Fall—humerus fracture |

15 | Multiple | 3 unwitnessed by staff |

2 person assist mechanical standing aid Non ambulant |

| 6 | 85 | Male |

Fall—hip fracture, radius fracture *Aphasia |

10 | 1 | 0 |

2 person assist sling hoist Non ambulant |

| 7 | 77 | Male | Stroke | 15 | Multiple | 0 | 1–2 person assist two wheeled frame |

| 8 | 90 | Female | Fall with long lie | 20 | Multiple | 0 | 1 person assist four wheeled frame |

| 9 | 90 | Female | Stroke | 15 | Multiple | 0 |

2 person assist sling hoist Non ambulant |

| 10 | 93 | Male | Haematuria, functional decline, delirium | 15 | Multiple | 2 unwitnessed | 1 person assist four wheeled frame |

| 11 | 71 | Male | Delirium, bipolar disorder | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 person assist two wheeled frame |

- Abbreviations: CALD, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse; FIM, Functional Independence Measure.

3.2 Participants' experiences of alarms mapped to the Person-Environment-Occupation model

Data from interviews, observations, and medical record analyses were mapped to the PEO model as illustrated in Figure 1.

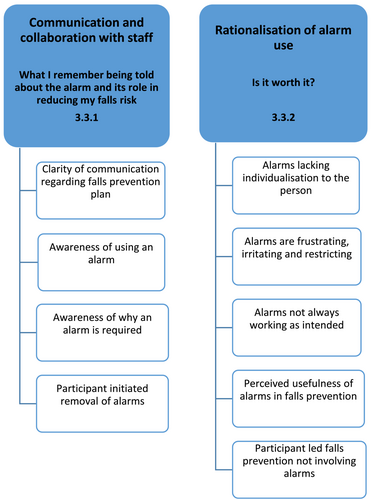

3.3 Themes

Data from interviews, observations, and documentation analyses were organised into nine categories linked to two overarching themes: communication and collaboration with staff and rationalisation of alarm use (Figure 2).

3.3.1 Communication and collaboration with staff

How staff communicated and collaborated with participants impacted how they experienced alarms. These experiences were grouped under four categories: clarity of communication regarding falls prevention plan; awareness of using an alarm; awareness of why an alarm is required; and participant initiated removal of alarms.

Clarity of communication regarding falls prevention plan

No participants recalled falls prevention plans being discussed with them. Participants expressed awareness to only walk with assistance; however, this was not explicitly referred to as part of a communicated falls prevention plan. Staff regularly documented in medical files that requests were made to participants to use the call bell but participants were not observed to use the call bell on any occasions during the observation sessions and staff were not observed to remind them.

Two participants (4 and 7) indicated staff suggested the alarm was in use to prevent them from falling. There was no explicit recall of education that alarms were part of a multifactorial falls prevention plan. Some participants referred to alarms being ‘extra back up’ (P11) and ‘something added’ (P7), suggesting awareness that alarms are just one aspect of a larger falls prevention plan. Some participants stated that although staff were focussed on falls prevention, specific strategies regarding how they could personally reduce falls were not communicated.

They keep reminding me, they say ‘I don't want you to fall’, that's all. (P4)

Staff busyness, language barrier, and the complexity of falls were suggested as reasons for this lack of communication.

They have never got time to really sit down and explain (the alarm), but ah, well they could. (P1)

Maybe they talk, because of the language barrier, no language. (P3)

It would be very difficult for them (staff) to do that (discuss falls prevention), wouldn't it? How can you tell someone, ‘don't fall’. You can't can you?. (P2)

Awareness of using an alarm

Reassurance given (to wife), explained that we do hourly rounding and patient has alarm in situ. (P6 file note)

Participants' awareness of using an alarm was influenced by transactions between the Person-Environment domains, specifically staff's lack of explanation of alarms.

It was just put there …. I wasn't even told they were putting it on … I've never been told, ‘we're putting this here’, the nurses just push you aside, put it on and they don't tell you why or anything. (P1)

Somebody said, ‘oh, and you need this’ and put it on my bed … Look, I didn't know it was an alarm. I had no idea. I just thought, ‘well what use is that?’ It's got no plugs, no this, no that, it's just a strap. (P2)

They just put it under my sheet. They put it on at night. So that was what I knew about it. I would be happier if they asked … in the first instance … what the hell is that for? (P7)

Are they aware that they have got it there? Because they may not want it there …. It is all about communication with the maker, the hospital and the patient. I'm a big one for respect for the patient … the patient should come first. (P11)

Awareness of why an alarm is required

Two participants indicated the alarm was required due to personal factors (dizziness and delusions) (Person).

If I was a bit delusional, I might hop out of bed when it is inappropriate to do so. (P9)

Participants were aware the alarm triggered a staff response (Environment) but did not relate this back to their own impairment, for example, poor balance and forgetting to call for assistance (Person).

They (staff) care to monitor so I don't get up and walk by myself. (P4)

Only P1 recalled an explicit explanation, albeit brief, of why they required an alarm.

They all said, ‘if you fall over’. (P1)

Some participants thought they did not require the alarm all the time but felt obliged to adhere to staff recommendations.

You feel as if you should go along with the hospital, but it gets a bit much when you're on it all the time. (P1)

To me, maybe I don't need it 24 hours. It really depends, if the patient is more active, you may need. To me, I believe in the day time I might not need, in the evening I need. (P3)

Participant 11 erroneously thought alarms were provided to everyone.

I think they just put it on every bed. (P11)

Two participants thought alarms had a purpose beyond falls prevention.

If I wet the bed. (P9)

Insecure … about someone coming in and attacking you or there is a fire somewhere and they may have forgotten you. (P11)

Participant initiated removal of alarms

Four participants disagreed they required an alarm by virtue of requesting or removing it. Occasionally, participant preference was over-ridden; other times, negotiation was documented between staff and participants.

Patient removed alarm from chair—reapplied. (P1 file)

Patient complained ‘it's too loud, every time I lift my bottom up. Take it away.’ Staff continued to use due to patient impulsive. (P4 file)

Refused alarm. Writer explained importance of alarm … still refused. Writer told patient to use buzzer if not wanting alarm. Patient agreed to have alarm overnight. (P5 file)

On occasions, staff met participant preferences through observations of their responses to alarms. Alarms were removed on two occasions due to observed negative impacts.

Alarm not used due to distress of patient. (P8 file)

Patient became more unsettled with alarm. (P7 file)

3.3.2 Rationalisation of alarm use

A range of factors impacted whether alarms were perceived of value. These factors were grouped under five categories: alarms lacking individualisation to the person; alarms are frustrating, irritating, and restricting; alarms not always working as intended; perceived usefulness of alarms in falls prevention; and participant led falls prevention not involving alarms.

Alarms lacking individualisation to the person

There was a lack of tailoring of how alarms were used to meet specific participants' needs. Following falls, there were some revisions to participants' falls prevention plans, such as recommending a high visibility room, but reconsideration of the role of alarms was not documented, except in one instance when a new alarm was suggested given the current alarm was assumed faulty. Some participants had documentation of improved ability to use the call bell; however, no documentation revealed reconsideration of the need for the alarm to reflect this improved ability.

Neither interviews nor documentation analyses revealed whether alarms were required in specific positions (i.e., bed, chair, or both bed and chair) or parameters (alert to sound at the bedside or only through the nurse call system) (Environment) according to individualised risks or preferences. There was a sense that alarms were introduced as routine practice but lacked follow-up review of their benefit.

I dare say they have got a few. But nobody has questioned the fact that it was given to me and never returned. (P2 had removed the alarm themselves)

One participant claimed to like the alarm due to a perception that it was a hospital requirement. However, documentation analysis revealed they attempted to switch the alarm off, indicating a desire to individualise care according to their preferences.

I like it because this is a requirement from the hospital, I have to obey it. (P3)

Alarms are frustrating, irritating, and restricting

Negative experiences of alarms included alarm hypersensitivity, perceived negative reactions from nurses, physical discomfort, and a sense of restraint.

They (alarms) can be so frustrating. They really do make one feel angry. (P2)

It was very uncomfortable and I didn't like it, it just irritated me. (P2)

When you see it, you think ‘Yuk’. I feel as if ‘that's there again’ and I can't move because when you're in bed you forget about it and you move a little bit and a nurse will come in switching everything off again. (P2)

Participant 5 believed there was a relationship between how one feels about alarms and how effective they are at reducing falls.

If you resent them, I think they (alarms) wouldn't be so successful. (P5)

Alarm oversensitivity was the prominent feature causing distress, particularly at night time disturbing sleep.

Too sensitive, the moment you wriggle your bum it starts to go off. (P4)

You can tell by their (staff's) body language, they're not shitty, but after a couple of times they get … because after the first one goes off they come and fix it up, then I try again to get to sleep because I'm sensitive of not getting any sleep and upsetting them during the night. So it is a broken sword because by trying to help them, get to sleep, I have to move around and senses that off. (P11)

If you move a little bit, you bring in a nurse and she is turning off all the buzzes. That's a lot, all through the night. (P1)

How staff responded to alarm alerts impacted the subsequent nurse-participant interaction. During an observation session, a nurse conveyed the alarm hypersensitivity interrupted their ability to perform essential duties. Participant 3 (CALD) moved frequently trying to access items within his room. The alarm triggered twice in a few minutes. The nurse turned the alarm off, reporting ‘I need to get some work done’. Participant 3 appeared frustrated at the inability to communicate his needs and at requests for him to return to bed.

Physical discomfort associated with alarms was highlighted, either because of body type (Person) or alarm design. Participant 7 moved frequently in bed and suggested this was, in part, due to discomfort from the alarm.

It annoyed me (the alarm) being so thin … it annoys my back. (P7)

Factors relating to the Occupation domain were rarely discussed or observed, except when discussing a sense of restriction and negative impacts on ability to toilet and sleep. Participant 11 exclaimed ‘shut up’ and swore when their alarm triggered while attempting to transfer unassisted. They later highlighted ethical considerations regarding restraints.

You can't beat them (alarms), so you have to sort of angle-angle to outwit it … A straight jacket … it reminds me of … Where do you stop if you have a patient with a strap underneath, what's the next step? (P11)

There were tensions between participants' desire for independence, particularly around self-care, and complying with staff's recommendations to not walk unsupervised. An unequal relationship appeared to exist between staff (Environment) and participants (Person). Participants felt that staff determined when they could mobilise, rather than making this decision themselves.

I got up on my own (to the bathroom) … it is not too nice … you get out there and trundle around … they (nurses) came to me after I got to the toilet. I don't know …. whether it is worth it or not. (P6)

I was supposed to wait … I had the towels there so I thought I might as well save her time, plus … I can shower myself, I have worked out to move stuff … so I was showering … and I felt a bit wonky and I thought, ‘Oh (profanity), I'm gone here’ and I wasn't worried about hitting my head, I thought ‘Oh Christ what are the nurses going to say?’ (P11)

Staff will ask you to (press) the button, why you can't get up and why you can get up. (P5)

Other times, the alarm successfully discouraged walking unsupervised due to worry about setting off the alarm and causing additional work for staff which participants perceived would have been received negatively.

Quite a few times when I was laying down I was thinking, ‘that wretched thing, I want to go to the loo, I can't go to the loo’ because the buzzer would go off … quite annoyed about that. (P2)

It stops me, apparently I got out of bed when I was not allowed …. It is tempting to go to the lavatory, if you are in a hurry. (P5)

Alarms not always working as intended

Medical records indicated alarms did not alert staff that participants were mobilising unassisted on any of the seven falls. Five participants identified alarms worked as intended by detecting movement and triggering a staff response, promoting a Person-Environment transaction.

The nurse will come. Turn the thing off and ask me why I want to walk. (P4)

You're sitting on it and … when you move … you disturb it and it causes the alarm to go off. Then all hell breaks loose, everybody is looking for you. (P9)

Alarms were observed to be switched on and positioned correctly under participants for 66% of the observation sessions. Other times, the alarm was not located where the participant was or was not switched on. With the exception of P1 and P2, alarms activated at least once for all participants during scheduled observations. Twenty-six alarm activations occurred in total. Alarm triggers were spread evenly between true and false alerts (Table 4). Staff responses ranged from assisting mobility, checking if the participant needed anything or were uncomfortable.

| Alarm position on/off | Number of times observed | Type of alarm alert | Alarm alerts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alarm in position and switched on | 14 | True alarm (triggered as intended, full postural change of participant) | 9 (34%) |

| Alarm in position but only switched on part of session | 3 | False alarm (triggered erroneously, only slight positional change of participant) | 9 (34%) |

| Alarm in position but not switched on | 2 |

Staff error false alarm (staff assist participant to move, forget to switch alarm off) |

8 (32%) |

| Alarm not positioned under participant | 2 |

No alarm (not triggered despite full postural change of participant) |

0 |

|

Total observation sessions 21a Total observation time 20 h 10 minb |

Total alarm alerts observed 26 |

- a One session not conducted because P1 refused alarm.

- b Four sessions interrupted due to ward activities.

Perceived usefulness of alarms in falls prevention

Some participants perceived alarms as useful particularly when staff could respond promptly to alerts.

These are very useful to me because sometimes I feel dizzy and it is good for my safety. (P3)

It feels as though you are not neglected … (and I) felt spoilt. (P7)

If I sit up, or try and stand by myself and I am having trouble. (P10)

Other participants were ambivalent. They thought alarms were useful for others, rather than themselves, based on others being older, more active or with particular medical conditions, such as dizziness or confusion.

I think it could be very useful for very old and fragile … who are a bit … scrambled … It would be useful for warning staff that one of their patients was in danger of hurting themselves. (P9)

If you have got different people … he (referring to co-patient) just doesn't walk … he doesn't need it (P6) I think that (the alarm) could be quite upsetting for someone younger. P1 thought she handled the alarm better than on a previous admission ‘probably because I'm older’ (P1)

At my age, I really don't think I need one … They are probably 80% good, for the right person, in the right age group and the right mental state … the lady beside me is probably 10 to 15 years older … she definitely needs one. (P11)

Usefulness of alarms to achieve Person-Environment transactions (nurse entering room) was highlighted. But some questioned alarms' efficacy in preventing falls, emphasising falls were unavoidable or staff response is what determines alarm effectiveness.

If you're going to fall, you fall, and I don't think that's (the alarm) got anything to do with it. (P1)

I don't think they actually stop people from falling. I just think they warn. It is not that they actually stop them. How would it stop them? (P9)

I don't think it is useful. I think that (alarm) summarises … how often you get up from the bed. Now, this is half a dozen times or two times? What matters is what comes after (i.e. staff response). (P6)

Participant led falls prevention not involving alarms

Participants reported using a range of strategies to reduce falls that were not reliant on alarms: being more active, cautious, vigilant of environmental hazards, and using the call bell.

Try and push yourself … provided you do it within the rules. I'm trying to do more exercise and … be more positive. (P11)

Think before you take that final step. It is important. You know if you just go ahead, then you fall. (P8)

Just make sure I've got something I can grab onto. (P10)

Every time I go to the toilet, I touch the (gestures pressing button). (P6)

Others nominated limiting walking as the only option to reduce falls.

I don't move unnecessarily, that's all I can do. (P4)

4 DISCUSSION

There is a dearth of research exploring falls prevention strategies from the perspectives of those with cognitive impairment. Many of the problems experienced in caring for older adults with cognitive impairment are interpersonal and occur in the communication process. To be authentically person-centred, it is crucial that we prioritise communication to understand older adults' preferences and experiences of alarms. Participants in this study, despite varying degrees of cognitive impairment, shared valuable insights into their experiences. These were explored through the lens of the PEO framework. The two overall themes identified were communication and collaboration with staff and rationalisation of alarm use.

There was a dominance of negative experiences for the older adults using alarms. Previous research has shown alarms are associated with feelings of discomfort, frustration, restriction, and paternalism in those without cognitive impairment (King et al., 2021; Radecki et al., 2018). This study found a lack of communication, alarm hypersensitivity, and a sense of restriction were the main sources of dissatisfaction. The negative impacts and reduced motivation of older adults to use alarms suggest their use needs further consideration and potential tailoring to individual needs.

The positive feelings some participants expressed of alarms being useful are potentially misguided given their questionable efficacy and not always working as intended. Some participants expressed alarms were useful at preventing falls for others but not themselves. Older adults often have a ‘better for others than me’ perception with regard to falls prevention because they believe they are not at risk of falls, have different strategies in place, or feel unable to participate in the strategy (Haines et al., 2014). Participant suggestions of falls strategies they could implement were somewhat limited, thus highlighting the importance of falls education. This study demonstrated a lack of education, or poor retention of it, which is concerning. A recent meta-analysis on a variety of falls prevention interventions found falls education was the only intervention that demonstrated statistical significance at effectively reducing hospital falls (Morris et al., 2022). Undoubtedly education of those with cognitive impairment is more challenging. A scoping review of education for adults with cognitive impairment in hospital identified that education should be individually tailored, mixed modal, jargon free, and repeated multiple times across the admission (D'Cruz et al., 2021). Older adults in this study may have benefited from this education approach, whereby information regarding the risks versus benefits of alarms could have been presented in an accessible way to allow them (or family) to make an informed decision to use an alarm or not, instead of a sense that it was imposed on them.

Staff often developed falls prevention plans, including the use of alarms, with little collaboration from the older adults who had to follow these plans. This shows a unidirectional staff led approach to care that creates power imbalances, possibly driven by reduced time and staff concerns regarding the ability of those with cognitive impairment to comprehend the information (Haines et al., 2012). Research into patient preferences of hospital care revealed a desire to be involved in decision making processes and to feel safe to accept or reject proposed interventions; however, at times, power imbalances prevented active participation, and patients felt ignored or inferior (Ringdal et al., 2017). Participants in this study appeared to experience similar power differentials despite having an interest and willingness to be involved in decisions surrounding their care. A summary of our research findings was requested by 91% of participants demonstrating a desire to be engaged with their healthcare.

There is potential to debate whether alarms could be considered a form of behavioural restraint based on how participants felt alarms restricted their mobility, such as not being able to walk to the bathroom when desired or make positional adjustments in bed to improve comfort. Restraints are associated with potential psychological harm and loss of dignity. Specifically exploring these concepts was beyond the scope of this study; however, it is known that allowing people to have occupational choice and control is critical to wellbeing (Townsend & Polatajko, 2013) and in some circumstances, alarms removed this choice and control. Older adults' can experience a contrast between high levels of meaningful occupational engagement prior to hospital, and scarce occupational opportunities in hospital, with large amounts of time spent waiting for care (Cheah & Presnell, 2011). Introduction of an alarm could further reduce activity levels in hospital potentially contributing to deconditioning and functional decline.

Despite a restricting effect, some participants rationalised liking the alarm on the basis it was hospital policy. Adults can have an unwavering trust in health care professionals, despite restrictive interventions being insufficiently explained (White et al., 2019). Health professionals are encouraged to use approaches that foster autonomy, engagement, and respect when considering potentially restrictive interventions. The Australian best practice guidelines for preventing falls in older adults in hospital directs clinicians to consider the ethical implications of the intrusive type of monitoring alarms subject people to (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2009). To do this, therapists must negotiate tensions between enabling dignity of participation while managing risk (Stanley et al., 2022). Testing physical boundaries is common among patients (Gettens et al., 2017; Haines et al., 2012), and participants in this study had different appetites for risk. Therapists could consider older adults' individual appetite for risk and ability to implement their own falls prevention strategies, as these are likely to contribute to whether alarms are experienced as restrictive or not.

Using the PEO framework keeps the older adult at the centre of the experience. The framework highlights how a relatively straight forward intervention, a leather sensor strap placed on the bed or chair, can evoke positive or negative experiences depending on the unique person, occupation, and environmental factors involved (Figure 1). The literature reveals no clear indicators for who, when, and how alarms should be used with older adults, except that there are multiple facilitators and barriers to effective alarm use (Mileski et al., 2019). It is possible the ward culture, rather than personalised falls risk assessments, guide the use of alarms (Staggs et al., 2020). There needs to be consideration regarding the use of alarms and if they are being used as part of a dominant ward culture, organisational risk governance, or for actual patient safety. Although evidence on their effectiveness in preventing falls remains inconclusive, frameworks such as the PEO can guide clinical reasoning whether alarms would enhance or inhibit congruence of PEO domains and could avoid what some participants experienced as a ‘blanket approach’ to alarms.

Communication and time to discuss what matters to people appear to be important if there is to be collaboration and a person centred approach to falls prevention. Although this study was completed in a GEM ward with better access to allied health than the acute setting, reduced length of stay and time constraints mean all disciplines' time is limited, and a team approach to falls prevention and decisions regarding alarms is important so that not one discipline is relied upon. Nevertheless, occupational therapists are well placed to have individualised discussions with older adults and their families regarding falls prevention because of their skills in facilitating return to meaningful occupations that may involve high fall risks. Unlike nurses, who are responsible for multiple patients simultaneously on a ward, occupational therapists might have more time to spend with individual patients to assess if an alarm is the right fit for them as well as role model to other disciplines how to collaboratively address falls risk with older adults. It could involve initial discussions explaining the purpose of the alarm and why it is being suggested; investigating previous alarm experiences; confirming the person has a low appetite for risk and are unreliable in requesting assistance; gaining informed consent (Person factors); understanding preferences regarding occupational routines, for example, toileting (Occupation factors); setting alarm parameters according to the person's movements; consulting regularly with the person and their family regarding alarm usage; and ensuring there is sufficient staffing to respond to alarms in a positive manner (Environment factors).

It is recommended further research investigates both family and staff experiences of alarms, including how these may or may not differ between disciplines such as nursing, medical, and allied health. This study demonstrates it is possible to conduct research to understand the experiences of those with cognitive impairment in hospital. Additional research is recommended to explore older adults' (including those with cognitive impairment) experiences of other falls prevention interventions, for example, floor-line beds.

4.1 Limitations

Findings are limited to one ward within one hospital in Victoria, Australia. Results cannot be extrapolated to the broader population but may inform further studies exploring acceptability and/or effectiveness of falls alarms. Lack of documentation or participant recall of events, for example, consultation regarding alarms, does not mean it did not occur. Observation sessions and medical record analyses, as an extra means of data collection, served to minimise this limitation. Potential flaws in the interview design could have been identified had it been piloted. However, the semi-structure nature allowed personalisation of interviews as required, accommodating varying levels of cognitive impairment. Time constraints and concerns surrounding participants' comprehension meant they were not provided with opportunities to member check data analysis to verify themes were reflective of their experiences. Inclusion of staff perspectives in this study could have strengthened the findings but was beyond the scope of this project due to resource constraints. This study explored older adults' experiences with a standard sensor belt. With advances in technology, different devices may elicit different experiences.

5 CONCLUSION

Older adults in this study commonly reported negative experiences associated with alarms and a strong desire for consultation regarding specific ways to reduce their risk of falls in hospital. Cognitive impairment does not preclude people from wanting to be involved in decisions surrounding their care. Occupational therapists have the training to collaborate with people with cognitive impairment and assess the usefulness of alarms in reducing falls based on how they interact with their unique person, environment, and occupation domains.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kelly Stephen conceptualised, wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript with guidance from Alison Campbell.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank the older adults who participated and Eastern Health for supporting this research. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

K. S. is an employee of Eastern Health where participants were recruited but does not work at the specific hospital of recruitment.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.