Using PRPP-Assessment for measuring change in everyday activities by home-based videos: An exploratory case series study in children with multiple disabilities

In memoriam: Dr Esther Steultjens contributed extensively during this research but was no longer with us finishing this article. Her input during the research was extremely valuable.

Abstract

Background

Currently, paediatric health care aims to use a child-centred tailor-made approach. In order to design tailored occupational therapy, the implementation of personalised occupation-based measurements that guide and evaluate goal setting and are responsive to change is necessary.

Purpose

Primarily, this study explored the potential of the Perceive, Recall, Plan, and Perform (PRPP) assessment to measure the change in the performance of children with multiple disabilities. As a secondary evaluation, the feasibility of the PRPP-Intervention in a home-based program to enable activities was described. The overall aim is to show the potential of the PRPP-Assessment as an outcome measure to use as a base for designing tailor-made person-centred care.

Methods

An exploratory longitudinal multiple case series mixed-methods design was used. The PRPP-Assessment, scored by multiple raters, was conducted based on parent-provided videos. The assessed activities were chosen by the child and/or parents. Responsiveness was evaluated by hypotheses formulated a priori and by comparing measured change with change on concurrent measures: Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) and Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). Over a 6-week period, children and their parents (or caregivers) participated in an online home-based video coaching program where parents were coached in the implementation of the training, based on the PRPP-Intervention, by paediatric occupational therapists on a weekly basis. The feasibility of the intervention was explored using semi-structured interviews with children, parents, and the treating occupational therapists and was analysed by directed content analysis.

Results

Three out of 17 eligible children agreed to participate and completed post-intervention measurement, of which two completed the intervention. Quantitative results showed that eight out of nine activities improved on the PRPP-Assessment and the COPM, and nine improved on the GAS. In total, 13 out of 15 hypotheses for responsiveness were accepted. Participants experienced the intervention as successful and acceptable. Facilitators and concerns over demand, implementation, practicality, integration, and adaptation were shared.

Conclusion

The PRPP-Assessment showed the potential to measure change in a heterogeneous group of children. The results indicated a positive tendency for the intervention and also provide directions for further development.

Key Points for Occupational Therapy

- Using the PRPP-Assessment as an evaluative measurement requires careful task selection and criterion formulation.

- Fixed-task analysis and similar contexts between measurements enhance the longitudinal validity of the PRPP-Assessment.

- The PRPP-Intervention in an online home-based video coaching context can improve everyday functioning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Paediatric health care is shifting to give more attention to a child-centred tailor-made approach, also referred to as person-centred care (Coyne et al., 2016). In addition, e-health, or telemedicine, has gained momentum with health professionals in paediatric care over the past few decades (Strehle & Shabde, 2006). The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated these developments and has served as an impetus for care-at-distance (Doraiswamy et al., 2020; Monaghesh & Hajizadeh, 2020). These developments challenge paediatric care to provide child-centred care at distance, which we, in the following, will refer to as home-based care.

Child-centred home-based care can be beneficial for children with multiple disabilities for many reasons. First, with home-based care, the child can learn and apply skills in their own environment. It is known that training in the home environment is beneficial to the long-term effects of therapy; the more similar the context, the better the transfer of learning (Eslinger et al., 2013). Second, it avoids (long) travel times, thereby enhancing accessibility to treatment and reducing the burden on the child and their family. Third, home programs can enable a higher frequency of training, thus contributing to its effectiveness (Tinderholt Myrhaug et al., 2014). Last, the involvement of parents in home programs can increase parents' knowledge of skill acquisition as well as their self-confidence (Beckers, 2019).

To be able to design tailored care that focuses on activities that matter for the child and show that this is effective, we should be able to measure occupational performance, on a personalised level, using instruments that guide and evaluate goal setting and are responsive to change (de Vet et al., 2011). In addition, for home-based care, the measurements need to be ecologically valid, which means that the outcome should represent behaviour in the ‘real world’ (Schmuckler, 2001). To be applicable to all children with multiple disabilities, an assessment needs to be flexible enough to measure personalised goals with various levels of functioning. In this case series, we included children with a mitochondrial disorder, who can serve as representatives of children with various levels of functioning due to fatigue, speech and language problems, muscle weakness, and/or developmental delay (Koene et al., 2013). Mitochondrial disorders can affect multiple different organs, and the symptoms can vary depending on underlying genetic defects. Some children have a severe cognitive impairment, while others have normal cognitive development but suffer from (cardio) myopathy. Symptoms such as epilepsy, dystonia, ataxia, exercise intolerance, deafness, and retinopathy can, among others, also occur (Koene et al., 2013). Health care regarding children is mainly coordinated by a university expertise centre, but the treatments required can vary. Children with mitochondrial disorders are treated in rehabilitation centres (special education), schools, private practices, and specialised hospitals. In this regard, there are a range of treatments from medical to allied health care including physical therapy, speech therapy, dietetics, and occupational therapy—there are also children who only attend a specialised hospital once a year for a check-up, without any further involvement of health care professionals. Furthermore, mitochondrial disorders are rare, which makes it difficult to develop evidence-based treatments, as research is challenging due to the heterogeneity of the disease and the limited number of individuals who are eligible to participate in any given study (Whicher et al., 2018). There is a need for patient-oriented outcome measures within this field of rare diseases (Potter et al., 2016).

The Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform (PRPP) System of Task Analysis and Intervention (Chapparo, 2017; Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), comprising the PRPP-Assessment and the PRPP-Intervention used by occupational therapists shows the potential for child-centred care-at-distance. The PRPP-Assessment has been applied to children with multiple disabilities, ranging from children with very limited functional abilities to typically developing children. In recent studies, the PRPP-Assessment has been found to be reliable and valid when using parent-provided videos of children with mitochondrial disorders performing meaningful activities (Lindenschot, Koene, et al., 2022). The PRPP-Assessment has been successfully used in pre–post-intervention studies (Challita et al., 2019; Fry & O'Brien, 2002; Juntorn et al., 2017; Lowe, 2010; Mills et al., 2016; Nott et al., 2008; Stewart, 2010; Sturkenboom et al., 2014), but its responsiveness in children with multiple disabilities, such as a mitochondrial disorder, remains unknown. The PRPP-Intervention is a task-oriented cognitive strategy approach that simultaneously focuses on task and strategy training within the context of everyday performance. After selecting meaningful activities based on the PRPP-Assessment, therapists plan interventions aimed at building strategy use across the four quadrants of the PRPP. This results in a thinking sequence to support task performance and follows the global strategy: stop, attend, sense, think, and do. Prompts are used to alert children to process the information required for task performance and are followed by more specific content-based prompts selected by the therapist based on findings from the PRPP-Assessment (Chapparo, 2017; Chapparo & Ranka, 1997). The PRPP-Assessment and PRPP-Intervention have not yet been studied in a home-based program context.

Therefore, the primary aim of the current study is to explore the PRPP-Assessment's potential to measure change in the meaningful activities of children with mitochondrial disorders. As this requires change, the PRPP-Intervention will be used in a home-based program, giving input for the secondary aim of this study: to describe the feasibility of this intervention.

2 METHODS

An exploratory longitudinal multiple case series mixed-methods design was used for this study, with a quantitative approach to explore the responsiveness of the PRPP-Assessment and a qualitative approach to explore the feasibility of the PRPP-Intervention in a home-based program.

Responsiveness was evaluated based on the COSMIN principles (Mokkink et al., 2009), by assessing longitudinal validity and reproducibility and evaluating the interpretability of the change scores. The change was measured using two concurrent validated measurements for the performance of everyday activities—the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS)—and compared with the outcomes of the PRPP-Assessment.

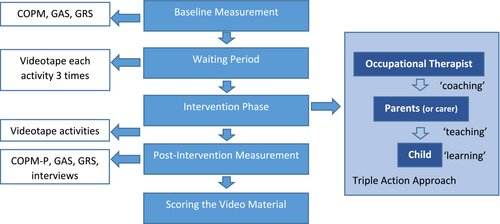

Enablement of daily activities was stimulated by a 6-week home-based video coaching program with the PRPP-Intervention following a triple-action approach (Figure 1). In this triple-action approach, the occupational therapist coaches the parent (first action). The parent trains the child (second action) in the home environment, and the child learns the new skill (third action) (Schnackers et al., 2018).

To evaluate the feasibility of the PRPP-Intervention in a home-based program, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the researcher (MR) with the children (when possible) together with the parents and caregiver(s), involved in the home-based program and the occupational therapists who performed the home-based program. Interviews were scheduled within 4 weeks after finishing the program—due to COVID-19, all interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams. The interview guide focussed on the experience of incorporating the intervention into participants' daily lives or practices, satisfaction, and encouraging/impeding factors. The interview guide for parents focussed on the guidance of the occupational therapist, whereas the interview guide for the occupational therapists focussed on the feasibility of generating a PRPP-Intervention plan based on the videos.

2.1 Participants

Children aged between 2 and 18 with a genetically confirmed mitochondrial disorder who visit the Radboud Centre for Mitochondrial Medicine for medical care were eligible for participation in the study. The prerequisites for participation were that the child wanted to improve two or more activities and did not participate in other studies. No exclusion criteria considering physical, cognitive, and communicative (dis)abilities were formulated to include a clinically representative sample. The aim was to include five to eight children. The treating physician sent a patient information letter to eligible children and their parents, and the parents were contacted again by telephone 2 weeks after sending the letter.

2.2 Design and procedure

The study was conducted in five phases (Figure 1).

2.2.1 Phase 1: Baseline measurement

After receiving confirmation of participation, an initial visit to the child's home was conducted by the researcher (ML). Based on shared goal setting, three activity goals for the intervention were chosen by the children and their parents. Goals were set with the GAS (Turner-Stokes, 2009), and instructions for videotaping the activities were discussed (Lindenschot, de Groot, et al., 2022). Baseline measurement with the COPM (Law et al., 1998) and General Rating Scale (GRS) (de Vet et al., 2011) was conducted. Combining the COPM and the GAS enables subjective and objective demonstrations of goal achievement (Doig et al., 2010).

2.2.2 Phase 2: Waiting period

There was an interval of 2 to 6 weeks before starting the intervention. During this period, parents videotaped the chosen activities of the child. Preferably, each activity was videotaped three times to gain insight into the performance stability of the activity and the child's functioning.

2.2.3 Phase 3: Intervention

The occupational therapists conducting the intervention were certified PRPP-Intervention therapists and had experience with video coaching for children with multiple disabilities. They did not receive additional training or support for this online video coaching. They were able to consult a PRPP-Intervention expert when designing the PRPP-Intervention plan if it was necessary. The occupational therapists developed the intervention based on videos of the activities, the GAS, and the criterion (i.e., task performance) using the PRPP-Assessment. Therapists planned the PRPP-Interventions using the global strategy: stop, attend, sense, think, and do. According to the guidelines, they also determined the prompts to guide the child through the activity. This PRPP-Intervention (Chapparo, 2017) was conducted in a 6-week ‘home-based video coaching program’ with a triple-action approach (Figure 1) (Schnackers et al., 2018). Paediatric occupational therapists coached the parents, who in turn taught the child how to learn the activities. In the first consultation, the occupational therapist discussed the PRPP-Intervention plan with the parent, and together, they decided on the focus for the next week. Parents videotaped their interactions with the child during task performance, forming the basis for the weekly online consultations (lasting 45–60 min). The occupational therapist discussed the videotape with the parents and focussed on what enabled the activity and which prompts the parents could use to further enhance learning. Parents were asked to try to train the activities with their child at least two times a week. The week after the last intervention session, parents videotaped the chosen activities for the last time.

2.2.4 Phase 4: Post-intervention measurement

Immediately after the 6-week intervention, a post-intervention measurement was conducted by the researcher (ML), collecting data on the COPM, GAS, and GRS. Parents (and children when possible) and the treating occupational therapists were interviewed separately regarding their experiences with the intervention via a semi-structured interview—these interviews took 15–25 min.

2.2.5 Phase 5: Scoring the video material

To collect the PRPP-Assessment scores, eight PRPP-Assessment-certified paediatric occupational therapists scored the video material. One occupational therapist scored all the videos and set the procedural task analysis for the other occupational therapists. Next, the seven remaining occupational therapists scored the videos of one or two randomly assigned children. All the occupational therapists received the video material without knowing if it was made pre- or post-intervention.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 PRPP-Assessment

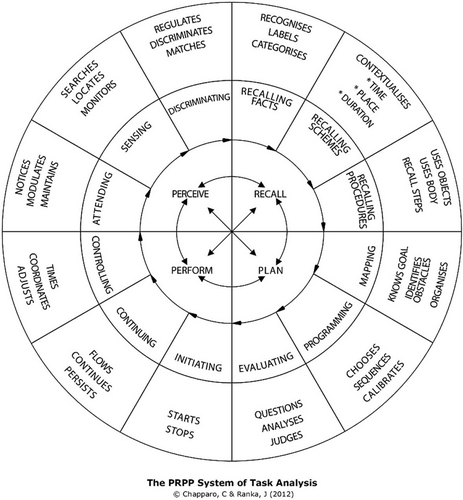

The PRPP System of Task Analysis is a two-stage, criterion-referenced measuring instrument that uses task analysis methods to examine the effectiveness of cognitive information processing during the performance of daily activities. In general, prior to the assessment, the child/parent and the occupational therapist agree on a meaningful task to be observed and the factors required for them to be satisfied with the task performance (the criterion). The outcome of the PRPP-Assessment represents the mastery of everyday activities and gives an analysis of the cognitive strategies used to gain a mastery score (referred to in this article as PRPP-M).

The PRPP-Assessment incorporates a task analysis procedure in Stage 1, in which an observed task is divided into relevant steps and the types of errors are measured. The PRPP-M of the task can be calculated by dividing the number of error-free steps by the total number of steps in the task. This gives a score for the level of the assessed activity: how well the child can perform this activity according to the predetermined criterion. Stage 2 of the PRPP-Assessment uses a cognitive task analysis and incorporates 35 items divided into the subscales of the PRPP-Assessment, which connects to a specific conceptual stage of information processing (see Figure 2). The 35 strategies include attention and sensory perception (Perceive Quadrant), memory (Recall Quadrant), response planning and evaluation (Plan Quadrant), and performance monitoring (Perform Quadrant). Each cognitive strategy is criterion referenced and evaluated on a 3-point scale, indicating how effectively the child used that cognitive strategy. This results in a total score between 35 and 105—higher scores indicate more effective cognitive strategy application—we refer to this Stage 2 sum score as PRPP-S (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997; Chapparo & Ranka, 2008).

In this study, the Dutch version of the PRPP-Assessment was used, with scoring criteria according to the PRPP-Assessment manual used in the 5-day PRPP-Assessment course for occupational therapists (Steultjens, 2016).

2.3.2 Other measurements

The COPM (Law et al., 1998) is a reliable, valid, and responsive instrument for measuring the perceived quality of performance and level of satisfaction (Cusick et al., 2007; Dedding et al., 2004; Verkerk et al., 2006), in which a 2-point difference (on the 10-point scale) indicates a clinically relevant change (Eyssen et al., 2011; Law et al., 1998; Verkerk et al., 2006). For analysis, the COPM-Performance (COPM-P) is used because it measures the same construct (activity performance) as Stage 1 of the PRPP-Assessment but subjectively, from a patient perspective.

The GAS is an individualised, criterion-referenced measure of change in individual goals (King et al., 1998; Kiresuk et al., 2014; Young & Chesson, 1997) that uses a scale from −3 (deterioration) to +2 (progress two steps beyond the goal). The GAS measures the same construct (activity performance) as Stage 1 of the PRPP-Assessment.

The GRS is reliable when measuring changes in a child's overall health status (de Vet et al., 2011; Kamper et al., 2010). The question, ‘How is your child's general health currently?’, was scored on a 10-point scale, with higher scores indicating better health.

2.4 Data analysis

Following the COSMIN guidelines (Mokkink et al., 2009), 15 hypotheses related to the size and direction of change and its association with other measurements were formulated a priori to support responsiveness (detailed information in Table 1). An acceptance of 75% of the hypothesis is seen as sufficient validity (Terwee et al., 2007). Hypotheses focus on longitudinal validity, longitudinal reproducibility, and the interpretability of score changes on the instrument, as these are the factors that need to be reviewed for evaluative instruments (Terwee et al., 2003). For longitudinal validity, the direction of change and the sensitivity to change between the scores on the PRPP-Assessment Phases 1 and 2, alongside the COPM and GAS change scores, were examined utilising percentages for expected relations and Spearman's Rho for correlations. Hypotheses were stated by the researchers (MR, ES, RN, and IG) based on their expertise and experience with the PRPP-Assessment, COPM, and GAS, as well as on the theoretical constructs of these assessments. For longitudinal reproducibility, the scores of all occupational therapists were used. For the other hypotheses, the scores set by one occupational therapist, who scored all the videos, were used. Longitudinal reproducibility was determined by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)agreement. An ICCagreement of 0.60 or higher is seen as acceptable (Landis & Koch, 1977). For interpretability, the differences in the PRPP-Assessment change scores of the activities that were clinically improved on the COPM when compared to the non-clinically relevant improved activities were reviewed. Data were collected and analysed using SPSS for Windows version 26.0 (New York, IBM Corporation, 2019).

| Hypotheses | Outcome | Accepted? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal validity | |||

| 1 | In 100% of cases, if the PRPP-M of Stage 1 and the PRPP-S of Stage 2 change, we expect the change to be in the same direction | 100% | Yes |

| 2 | In 80% of cases, if the PRPP-S of Stage 2 contains a change, then a change in the same direction is expected in the PRPP-M of Stage 1 | 89% | Yes |

| 3 | In at least 60% of cases, if there is a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1, we also expect a change in the same direction for the parent-rated COPM-P score | 100% | Yes |

| 4 | In at least 80% of cases, if there is a change in the parent-rated COPM-P score, we also expect a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1 | 89% | Yes |

| 5 | In at least 30% of cases, if there is a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1, we also expect a change in the same direction for the child-rated COPM-P score | 50% | Yes |

| 6 | In at least 50% of cases, if there is a change in the child-rated COPM-P score, we also expect a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1 | 75% | Yes |

| 7 | In at least 60% of cases, if there is a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1, we also expect a change in the same direction for the GAS | 100% | Yes |

| 8 | In at least 80% of cases, if there is a change on the GAS, we also expect a change in the PRPP-M of Stage 1 | 89% | Yes |

| 9 | The correlation between the scores of the parent-rated COPM-P and the PRPP-M of Stage 1 calculated with Spearman's r shows a moderate positive correlation (0.40 ≤ r ≥ 0.60) | 0.41 (p = 0.092) | Yes |

| 10 | The correlation between the scores of the GAS and the PRPP-M of Stage 1 calculated with Spearman's r shows a moderate to strong positive correlation (0.40 ≤ r ≥ 0.80) | 0.52 (p = 0.026) | Yes |

| Longitudinal reproducibility | |||

| 11 | The ICCagreement for the change scores of the Stage 1 PRPP-M is acceptable (≥0.60) (Landis & Koch, 1977) | 0.667 | Yes |

| 12 | The ICCagreement for the change scores of the Stage 2 PRPP-S is acceptable (≥0.60) (Landis & Koch, 1977) | 0.532 | No |

| 13 | The ICCagreement for the change scores of the Stage 2 quadrant scores are acceptable (≥0.60) (Landis & Koch, 1977) | 0.320–0.515 | No |

| Interpretability | |||

| 14 | In 100% of cases, if a clinically relevant change has occurred on the parent-rated COPM-P score (change score ≥2), we also expect a change in the same direction in the PRPP-M of stage 1 | 100% | Yes |

| 15 | If we look at the clinically relevant improved cases on the parent-rated COPM-P scores, we expect to see a higher mean change score compared to the non-clinically relevant changed and clinically relevant deteriorated cases | 100% | Yes |

- Note: A ‘case’ represents an ‘activity’, not a child.

- Abbreviations: COPM-P, the performance score on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM); GAS, the Goal Attainment Scale; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; p, p value; PRPP-M, the mastery score of the Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform (PRPP) assessment; PRPP-S, the sum score of the PRPP-Assessment.

The interviews were transcribed and analysed using directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), in which predetermined codes were based on the feasibility characteristics of Bowen et al. (2009). These codes included acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, adaptation, integration, expansion, and limited efficacy. The transcriptions were read, and sections of text were labelled with one of the predetermined codes. Next, the quotes were summarised among each code—the data were analysed with Atlas.ti 9.0.

2.5 Ethical considerations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee in addition to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, 2014). The ethical board of the regional research committee provided their approval (Approval Number 2021-8111, Trial Registration Number NL77169.091.21). All parents signed informed consent, and all raters signed a confidentiality agreement. Where indicated, the children also signed the informed consent to recognise their volition/agency (Stafford et al., 2003).

3 RESULTS

The patient information letter was sent to 17 eligible children and their parents. Eleven children refused participation in the study, of which eight declined because of situations that were too constrained (due to COVID-19, family issues, or hospital admittance), one child did not want to improve his activities, and for two children, the reason was unknown. Six children were willing to participate and met the inclusion criteria but two dropped out before the start of the intervention and one during the intervention period—they were too busy to be able to schedule appointments. Thus, four children started the intervention, but the post-intervention measurement was conducted with only three of the children. Age, gender, functional capacities, and the underlying aetiology varied. For privacy reasons, the exact age of the children and the genetic aetiology of the disease are not mentioned in the description of the cases, as this could threaten the anonymity of participants. A list of underlying aetiology can be provided upon reasonable request with the corresponding author. In the following section, we will first describe each case, followed by the overall outcome.

3.1 Description of cases

3.1.1 Xandra

Xandra is a girl of school age who was recently transferred to special education. She is delayed in motor and cognitive development, able to walk in and around the house, and is sufficiently self-dependent considering her young age. Despite minor speech problems, she is effective in communication.

Due to Xandra's young age, her mother chose three activities: dressing (taking clothes off and putting pyjamas on before going to bed), cycling (getting on/off a bicycle, cycling, steering, and braking), and social play (playing with friends through non-verbal interactions). Xandra was not able to score the child-rated COPM. Her mother videotaped each activity once during the waiting period. Mother and child were able to implement the intervention scheme of six sessions and trained in the activities weekly. Xandra's mother videotaped the activities during the intervention, and the occupational therapist gave specific instructions on how to improve guidance for the activities, which enabled Xandra to learn. Xandra improved on all three activities when measured using the PRPP-Assessment, the parent-rated COPM-P and the GAS—the GRS was stable.

3.1.2 Yara

Yara is an adolescent girl who is extremely delayed in cognitive development and has ataxia. She is sufficiently self-dependent and able to walk in and around the house but uses a wheelchair for long distances. Despite minor speech problems, she is effective in communication.

Yara chose her own activities to work on, which were applying make-up, putting in earrings, and tying shoelaces. Yara was videotaped performing each activity once during the waiting period. During the intervention period, Yara trained in the activities with her personal caregiver (who is a volunteer supporting Yara in her activities), and both were able to adhere to the intervention scheme. After six sessions, she improved on all three activities when measured using the PRPP-Assessment, the parent and child-rated COPM-P, and the GAS—the GRS was stable.

3.1.3 Zach

Zach is a boy of school age with an average level of cognitive development. He is delayed in motor development but is able to walk in and around the house, is effective in communication, and is sufficiently self-dependent.

Zach chose his own activities to work on, which were tying shoelaces, drawing a dinosaur and modelling his hair. Zach's mother videotaped each activity once during the waiting period. During the intervention period, his mother and Zach were not able to integrate the intervention scheme into their daily lives. They had difficulty establishing a video connection with the therapist, and after three partially successful connections, they decided to stop the intervention. They did train in modelling hair and tying shoelaces a few times, but drawing a dinosaur was not addressed. Zach reported that he felt more tired during and after the intervention period than before the intervention. His GRS, post-intervention, dropped by 1 point (from 8 to 7). Post-intervention measurement showed that Zach improved on tying shoelaces and modelling hair when measured with the PRPP-Assessment, the parent-rated COPM-P, and the GAS, but not on the child-rated COPM-P. He remained stable on the PRPP-Assessment for drawing a dinosaur but the child and parent-rated COPM-P and the GAS improved by 1 point.

3.2 Quantitative analysis of the responsiveness of the PRPP-Assessment

Of the 15 hypotheses formulated a priori for testing responsiveness, 13 were accepted, resulting in an 86% acceptance rate, which can be seen as adequate for measuring change (Terwee et al., 2007). Table 1 provides an overview of the statistical information for each hypothesis. Next, we will elaborate on each aspect of responsiveness.

3.2.1 Longitudinal validity

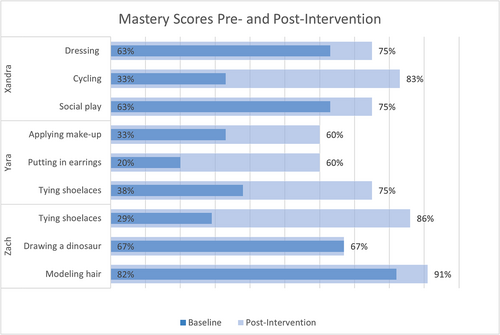

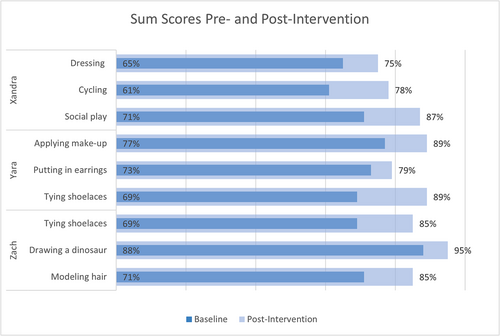

Overall, eight out of nine activities improved on the PRPP-Assessment. Figure 3 gives an overview of the pre and post-PRPP-M scores for the different activities, showing the child's proficiency when performing the activity without errors measured against the personalised criterion.

Figure 4 gives an overview of the sum score (PRPP-S) of the cognitive strategies used to perform the activities. A further specification of the (sub)quadrants can be found in the supporting information.

These results show that in all activities where the PRPP-M improved, the PRPP-S improved as well, and vice versa. However, in cases where the PRPP-S changed, the PRPP-M did not necessarily change as well; in all nine activities, the PRPP-S improved, corresponding to only eight improved PRPP-M scores. These outcomes resulted in the acceptance of hypotheses 1 and 2.

The scores for the COPM-P and the GAS are presented in Table 2, showing that in eight cases where the PRPP-M has improved, the parent-rated COPM-P improved as well. In one case, the PRPP-M remained stable. In this case, the parent-rated COPM-P deteriorated and the GAS increased from −2 to −1, demonstrating an improvement in skill acquisition to a level that did not yet achieve the stated goal.

| Case | Activity | PRPP-M | Child-rated COPM-P | Parent-rated COPM-P | GAS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | Change | T0 | T1 | Change | T0 | T1 | Change | T0 | T1 | Change | ||

| Xandra | Dressing | 63% | 75% | +12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 4 | 8 | +4 | −2 | +1 | +3 |

| Cycling | 33% | 83% | +50 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1 | 7 | +6 | −2 | 0 | +2 | |

| Social play | 63% | 75% | +12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3 | 7 | +4 | −2 | 0 | +2 | |

| Yara | Applying make-up | 33% | 60% | +27 | 2 | 10 | +8 | 5 | 8 | +3 | −2 | +1 | +3 |

| Putting in earrings | 20% | 60% | +40 | 1 | 7 | +6 | 1 | 8 | +7 | −2 | −1 | +1 | |

| Tying shoelaces | 38% | 75% | +37 | 6 | 10 | +4 | 6 | 9 | +3 | −2 | +1 | +3 | |

| Zach | Tying shoelaces | 29% | 86% | +57 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 4 | +3 | −2 | −1 | +1 |

| Drawing a dinosaur | 67% | 67% | 0 | 5 | 6 | +1 | 5 | 4 | −1 | −2 | −1 | +1 | |

| Modelling hair | 82% | 91% | +9 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 7 | +4 | −2 | −1 | +1 | |

- Abbreviations: COPM-P, the performance score on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM); GAS, the Goal Attainment Scale; PRPP-M, the mastery score of the Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform (PRPP) assessment.

It was expected that children would be less ‘reliable’ in their perceived quality of performance as they are more easily influenced by the moment (mood, tiredness, etc.). This was in line with the outcomes that showed less congruence between the PRPP-M scores and the child-rated COPM-P. There were six activities scored by children on the COPM-P. Three of these six activities improved both on the PRPP-M and on the child-rated COPM-P. For the other three, two remained stable on the child-rated COPM-P but improved on the PRPP-M, and one improved by 1 point on the child-rated COPM-P, while the PRPP-M remained stable.

For the GAS, all nine activities improved, and these outcomes resulted in the acceptance of hypotheses 3–8.

The correlation between the change scores on the parent-rated COPM-P and PRPP-M resulted in a Spearman's Rho correlation coefficient of 0.41 (with a p value of 0.092) and between the PRPP-M and the GAS, a Spearman's Rho correlation coefficient of 0.52 (with a p value of 0.026), leading to the acceptance of hypotheses 9 and 10.

Overall, all 10 hypotheses on longitudinal validity were accepted (see Table 1).

3.2.2 Longitudinal reproducibility

The ICCs of the Stage 1 PRPP-M and the Phase 2 PRPP-S and quadrant score are presented in Table 3, giving an acceptable reproducibility for the PRPP-M. The reproducibility for PRPP-S and the quadrant score did not reach 0.6. These outcomes resulted in the acceptance of hypothesis 11 but the rejection of hypotheses 12 and 13 (see Table 1).

| Change score | ICCagreement | ICCconsistency |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 mastery score (PRPP-M) | 0.667 | 0.688 |

| Stage 2 sum score (PRPP-S) | 0.532 | 0.592 |

| Stage 2 perceive quadrant | 0.382 | 0.442 |

| Stage 2 recall quadrant | 0.525 | 0.534 |

| Stage 2 plan quadrant | 0.320 | 0.376 |

| Stage 2 perform quadrant | 0.468 | 0.567 |

3.2.3 Interpretability

Of the nine activities, eight made a clinically relevant improvement on the parent-rated COPM-P, and they all improved on the PRPP-M. The one activity that did not make a clinically relevant change on the parent-rated COPM-P also did not change on the PRPP-M. These outcomes resulted in the acceptance of hypotheses 14 and 15 (see Table 1).

3.3 Qualitative analysis on feasibility of PRPP-Intervention

Five interviews were conducted: Xandra's mother; Yara, her mother, and her caregiver; Zach and his mother; Xandra and Zach's occupational therapists; and Yara's occupational therapist. Directed content analysis of the feasibility studies gave insights into several areas of focus: acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, integration, and adaptation (Bowen et al., 2009).

3.3.1 Acceptability

All participants were very satisfied with the content of the intervention. In their experience, it was easy, worthwhile, and successful—Xandra's mother stated: ‘I didn't expect to get such a result in such a short time. Even using care from a distance. Actually, just by making videos and discussing these in digital consultation’.

Even Zach and his mother, who did not complete the intervention, stated that the content of the intervention was good and helpful for improving the performance of daily activities. Xandra's mother was disappointed that the study was finished and would have liked to continue the treatment to reach more activity goals. Yara was extremely satisfied with the results.

Xandra gets speech therapy and physical therapy at school. It's a disadvantage that I am not present at the therapy. I can't see what it's happening during therapy. So, I can respond to that much less as a parent. That's why I do like this because now as a parent I know what needs to be done and can work with that.

She [Xandra's mother] was my target. She needs to give the therapy. If she would have visited my practice with Xandra, I would have demonstrated how to work with Xandra or would have given mother feedback on what Xandra does but we would not have reached this result. She [Xandra's mother] had to do it herself.

3.3.2 Demand

I think if you have a weekly appointment with Zach, he will be there. If we would help remind him and if you then make a list of what he needs to do and when …. When you structure and support this a lot as a therapist, then it should be possible …. But now I had to get involved more … I am busy too.

When the intervention was successful, the demand became more ‘acceptable’ for parents ‘because we saw that it helped, we also became more enthusiastic. If you have to do things that you do not see helping, then you are less motivated yourself’ (Xandra's mother).

3.3.3 Implementation

All the children and their parents were supposed to train in the chosen activities between the online sessions, but this was sometimes difficult to implement in their day-to-day lives. The parents stated that the activities are slightly longer than the training sessions and that they could be difficult to implement into their daily structure, as Yara's mother stated: ‘Before you know it, the week is gone’. Yara and her caregiver did find a way to make it easier to implement the training into their everyday routine by pretending that the videos during the intervention were a vlog. Zach's mother found it difficult to arrange a time in which both Zach and his mother were able to give their full attention to the training.

3.3.4 Practicality

To be able to carry out the program successfully, several practical aspects were important. First, the purely online aspect was new to all participants, with Yara saying that it was ‘a bit weird’ to just talk online. Second, not everyone knew the medium (the digital safe) used for coaching. This medium hindered the intervention with Zach, as his mother stated: ‘You should use what he understands and not such a difficult system’. Third, the occupational therapists needed to find a way to provide both the children and parents with the material they wanted to use in order to support the intervention. In all cases, the occupational therapists had sent information (pictograms, cards, or examples) to the children's homes. In some cases, this material was given digitally; for example, Yara received instruction videos (vlogs) for doing her make-up. Last, the occupational therapists mentioned that the online surroundings made it difficult to try certain tools that are available in the hospital. To this effect, Xandra's occupational therapist stated: ‘The mother has purchased a cycling vest herself, but sometimes you miss special tools or things that you have here in the hospital available to try’.

3.3.5 Integration

One occupational therapist had experience in video coaching, but for the other occupational therapist, it was the first time using this technique. Both felt that the intervention was naturally integrated into their usual practice. However, they sometimes felt limited by the videos; they would have liked the goals to be elaborated on or they were not able to clearly see what they wanted or needed for a full evaluation: ‘I couldn't really see if she had put the earring through the hole or not’ (Yara's occupational therapist). Both occupational therapists made appointments outside their usual office times as this better fit the parents and their usual work schedule.

3.3.6 Adaptation

Everyone agreed on the need for the involvement of the parents (and/or caregiver) and a good therapeutic relationship between the therapist, parents, and child. They felt that a hybrid format could enhance this therapeutic relationship; when performed with a home visit, it enhances the intervention because the occupational therapist becomes more familiar with the physical context and can be better incorporated into the intervention—Yara's occupational therapist noted that ‘when you go to the home you can really see what she looks like at her desk, what earrings she has or what shoes are in the closet. You can also say “Oh then we will start with these shoes.”’ The occupational therapists and Zach's mother stated that it would also be good to give more directions regarding the parental participation expectations from the intervention.

4 DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to explore the potential of the PRPP-Assessment to measure change in the meaningful activities of children with mitochondrial disorders. Results show the potential for the PRPP-Assessment to serve as an outcome measure for children. Furthermore, the PRPP-Intervention within a home-based video coaching program was experienced positively and resulted in clinically relevant improvements in eight out of nine activities.

The PRPP-Assessment aims to identify difficulties in the application of specific cognitive information-processing strategies during task performance. In addition, it generates an activity mastery score, giving an objective measure of the quality of performance. Although we compared the change scores of the PRPP-Assessment with the change scores on the COPM and the GAS in this study, the PRPP-Assessment is unique in measuring the construct of mastery score and cognitive strategy use. The COPM is a subjective measure of the perceived quality performance, whereas the PRPP-Assessment objectifies this score based on an observation. Although the directions of change were similar between the PRPP-M and COPM-P, the magnitude of change differed. This can be explained by the perceived change from the parent's perspective differing from an actual change from an occupational therapy frame of reference. The GAS is able to measure the change in individual goals in the same criterion-referenced way as the PRPP-Assessment but uses a limited scale of scoring. In addition, you need to know on which factors the child will improve, which are not always known beforehand. However, the COPM and GAS support that the change measured on the PRPP-Assessment is an actual change. The GRS was stable in all of the children, indicating that the measured change is not due to a change in overall health status but more likely due to the intervention and, more specifically, the measured activities. This is further supported by the differences in the cognitive strategy used for each child and activity when comparing baseline to post-intervention indicators. When measuring change with the PRPP-Assessment, not only the improvement in the level of activity is measured but the change is also explained by the cognitive strategy used. This makes the PRPP-Assessment valuable as an outcome measure in practice and research.

When using the PRPP-Assessment as an evaluative measurement, implications for practice and research were determined and they must be reproducible. First, the tasks and criteria (i.e., task performance) were carefully selected and formulated to ensure that there was enough room for improvement. This is in line with the recommendations of previous research (Lindenschot, Koene, et al., 2022). Second, this study used a fixed-task analysis, leading to an acceptable ICC for the PRPP-M and fitting the knowledge that this increases the reproducibility of measurement (Lindenschot, Koene, et al., 2022; van Keulen-Rouweler et al., 2017). Third, the context influences the validity of the measurement, and therefore, the measurement properties are dependent on the situation (de Vet et al., 2011). To illustrate, Yara used a new mascara for her post-intervention video, which made the brush glide easier and visible marks appear more quickly. Although Yara, her mother, and the treating occupational therapist felt that she could perform better, it was congruent with her current performance with the new mascara. Thus, to measure actual change, the context needs to be stable.

The participants' experience of the home-based PRPP-Intervention was successful in this study and is in line with current knowledge of home-based programs. According to Novak and Berry (2014), effective home programs adhere to three conditions: The program content needs to be designed upon proven, effective interventions; the program should be devised with regard to parent implementation preferences; and the parent should be supported and coached to successfully implement the program. Although, in one case, the adherence was not optimal as the parent implementation preferences were not optimally respected because the mother felt another medium should be used and the level of intervention required burdened her everyday life. In the other cases, all conditions were followed. The body of evidence for the PRPP-Intervention is growing (Challita et al., 2019; Chapparo, 2017; Juntorn et al., 2017; Nott et al., 2008), and we used a triple-action approach to coach the parents. In addition, qualitative analyses added three further conditions that determined success. First, the use of videos enabled parents to reflect on their own interaction with their child, thus increasing their knowledge, which again shows that home-based programs can increase parents' skill acquisition and self-confidence (Beckers, 2019). Second, the involvement of the direct context of the child is indispensable. Preferably the parent is involved because without them the triple-action approach cannot work. Third, the therapeutic parent–child and parent–therapist relationships are vital. This is in line with other findings that the therapeutic relationship impacts the effectiveness of interventions (King, 2017). To strengthen these therapeutic relationships further and increase the possibility to adapt the intervention to the physical context, a hybrid form for the home-based program was suggested. Overall, the home-based video coaching program with the PRPP-Intervention using a triple-action approach showed promising results and should be further developed and studied in children with multiple disabilities.

Another strength of this study was the decision to use the guidelines of the COSMIN (Mokkink et al., 2009), which divides responsiveness (Terwee et al., 2003) into longitudinal validity, longitudinal reproducibility and the interpretability of score changes. Whereas the hypotheses on the first and third aspects were all accepted, for longitudinal reproducibility, two out of three hypotheses were rejected. The scores of the two rejected hypotheses (the PRPP-S and quadrant scores) lacked variability, leading to underestimated ICCs and difficulty in forming substantial conclusions about the longitudinal reproducibility. However, based on the COSMIN guidelines, the results of the current study combined with previous research on reliability and validity (Lindenschot, Koene, et al., 2022) show that the PRPP-Assessment, in general, has sufficient to good psychometric properties.

A limitation of this study was the influence of the constrained family situations of the children. This not only led to a very small sample size but also to protocol deviations and premature termination of the study. However, the small sample size is common in research considering rare diseases, and this study generates substantial, in-depth information regarding a phenomenon that has not been previously studied, creating foundations for future studies. Unfortunately, the shared goal setting, which enabled the possibility for change in the key activities, did not solve the recruitment issues. We advise future studies on this rare condition to start with an evaluation of recruitment capability and the resulting sample characteristics (Orsmond & Cohn, 2015). We believe the constrained family situation of children with a mitochondrial disorder deserves more attention and care in research, as parental stress is known to be high in parents of children with disabilities (Cousino & Hazen, 2013; Gupta, 2007; Pinquart, 2018), which can lead to difficulty adhering to home-based programs (Beckers et al., 2019; Peplow & Carpenter, 2013). Despite the small sample size, this study enabled in-depth quantitative and qualitative data collection. Overall, despite its limitations, this study was successful in demonstrating the potential of the PRPP System of Task Analysis in a home-based video coaching program. Larger studies of children with multiple disabilities should further substantiate the results of this study and further investigate the intervention by studying the possible differences between parents' practice at home versus parents involved in the home-based video coaching program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Marieke Rothuizen-Lindenschot, Saskia Koene, and Imelda J. M. de Groot managed data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Esther M. J. Steultjens, Marieke Rothuizen-Lindenschot, and Saskia Koene managed development of the manuscript. Marieke Rothuizen-Lindenschot, Maud J. L. Graff, Imelda J. M. de Groot, Maria W. G. Nijhuis-van der Sanden, Esther M. J. Steultjens, and Saskia Koene contributed to the conception of the work. Marieke Rothuizen-Lindenschot, Maud J. L. Graff, Lonneke de Boer, Imelda J. M. de Groot, Maria W. G. Nijhuis-van der Sanden, and Saskia Koene contributed to the finalisation of the manuscript for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the children, parents, and occupational therapists who participated in this study.This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek [NWO]) (Project Number 023.009.016).

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, the 1964 Helsinki declaration, and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, 2014). The ethical board of the regional research committee provided their consent (number 2021-8111). The trial is registered nationally, number NL77169.091.21. All parents signed informed consent, and all raters signed a confidentially agreement. Where indicated, the children also signed the informed consent to recognise their volition/agency.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.