A Case of Pediatric Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis Evaluated for Liver Transplant Listing

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This publication was made possible by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) funded T32 (1T32DK127977-01A1) fellowship to R.B.S. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK.

Abstract

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) refers to liver injury from alcoholic intake that usually occurs after years of heavy alcohol abuse. Frequent, heavy alcohol consumption causes hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Some patients develop severe AH, which carries high short-term mortality and is the second most common reason for adult liver transplants (LTs) worldwide. We present one of the first cases of a teenager diagnosed with severe AH that led to LT evaluation. Our patient was a 15-year-old male who presented with epistaxis and 1 month of jaundice after 3 years of heavy daily alcohol abuse. In collaboration with our adult transplant hepatologist colleagues, we initiated a management plan that consisted of treating acute alcohol withdrawal, steroid utilization, mental health support, and LT evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) refers to liver injury from alcoholic intake that usually occurs after prolonged alcohol abuse (1). Frequent, heavy alcohol consumption causes hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Some patients develop severe AH, which carries high short-term mortality and is the second most common reason for adult liver transplants (LTs) (2). Severe AH involves acute onset jaundice, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine transferase>2, international normalized ratio (INR), and bilirubin >5 mg/dL (1).

It takes an average of 20 years of alcohol usage to develop AH and the mean age of presentation is 53 years (2). AH has been reported after excessive drinking for 3 months and in individuals as young as 20 years, but never in teenagers (3). We report one of the first cases of a teenager with severe AH evaluated for LT listing.

CASE REPORT

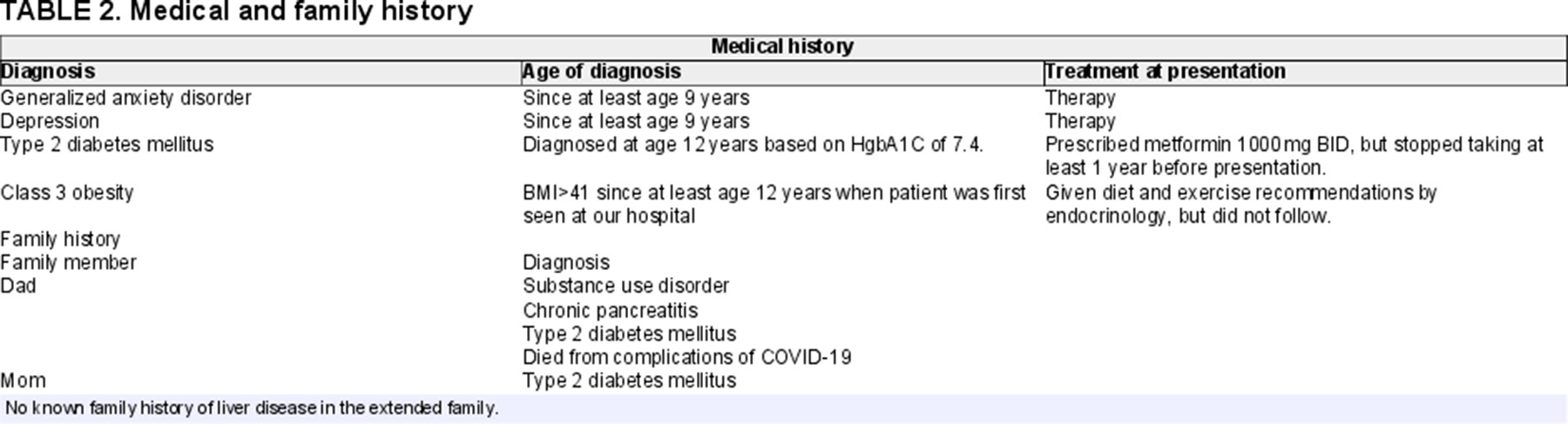

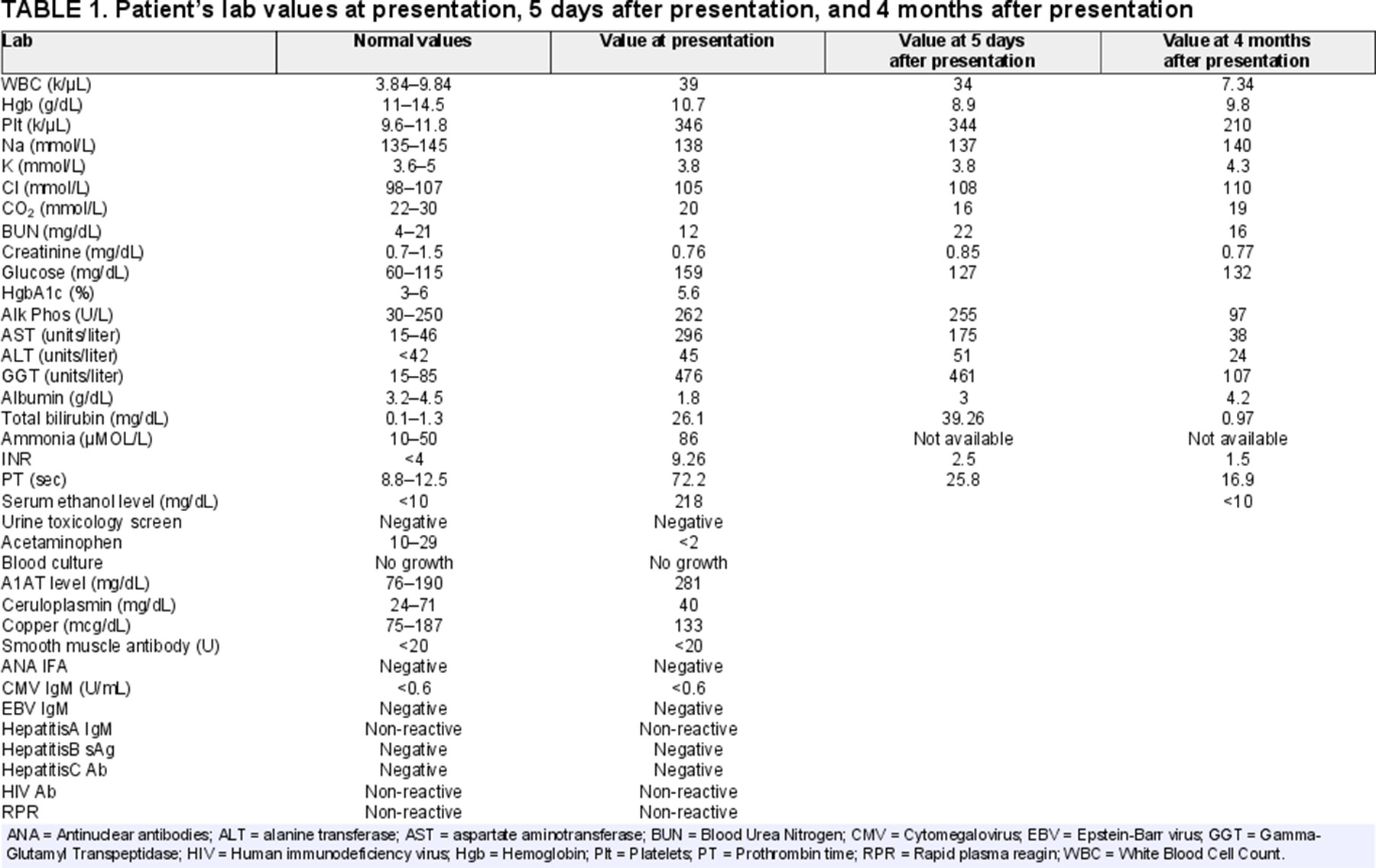

Our patient was a 15-year-old male with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), depression, class 3 obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus who presented with epistaxis and 1 month of jaundice after 3 years of alcohol abuse. Patient's alcohol intake began as occasional beers at age 12 years, progressed to daily beers at 13 years, and deteriorated to daily vodka pints at 14 years after his father's death. Table 1 contains medical and family history. The admission examination was notable for normal mental status, jaundice, scleral icterus, and hepatomegaly. Table 2 shows labs on presentation. Work-up for infectious, autoimmune, and genetic/metabolic causes of liver injury was unrevealing. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated marked hepatomegaly, mild splenomegaly, and diffusely abnormal vascular flow. Given the patient's alcohol-use history, elevated serum ethanol, and typical clinical presentation, he was diagnosed with acute liver failure from severe AH. Initial management included nothing by mouth, intravenous (IV) fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics until 48 hours of negative blood cultures, frequent neurologic checks, treating agitation and hallucinations from alcohol withdrawal (AW) with IV lorazepam 4 mg every 4 hours for 2 days (and then tapering off), and 3 days subcutaneous vitamin K 10 mg. We also consulted adult hepatology, given the rarity of pediatric severe AH, who recommended daily steroids based on an initial Model For End Stage Liver Disease of 40 and Maddrey Discrimination Function (DF) of 286. As the patient was nothing by mouth, we gave IV methylprednisolone 40 mg daily. No insulin was required for hyperglycemia. The patient was urgently evaluated for LT on day 3 of admission, which involved extensive discussion with the LT team (pediatric hepatologists, social workers, and surgeons), adult hepatologists, psychiatry, and psychology. The patient was recommended for LT followed by alcohol rehabilitation, but was ultimately not listed as insurance required 6-month abstinence.

While the patient's severe AH persisted, his INR decreased to 2.5 after day 5 of admission, so insurance was not appealed. Bilirubin rose and steroids were discontinued due to suspicion of ineffectiveness and concern for exacerbating underlying metabolic syndrome. After 3 weeks of hospitalization, INR stabilized at 2. The patient was eventually discharged with close LT follow-up and routine serum ethanol and liver function checks. Four months postdischarge, he was sober in alcohol rehabilitation. As Table 2 shows, his liver function normalized.

DISCUSSION

Despite our patient's severe presentation, he recovered without LT. Pediatric AH is challenging due to the inexperience of pediatric providers with extensive alcohol abuse and the inability to accurately extrapolate adult prognosticators. We discuss five considerations for pediatric AH management: (1) alcohol withdrawal, (2) steroid utilization, (3) mental health support, (4) LT listing, and (5) adult hepatology collaboration.

Alcohol Withdrawal

Hospitalized adolescents with heavy, prolonged alcohol usage require observation for AW using a validated assessment (4). AW can cause seizures, hallucinations, hypertension, and death. Benzodiazepines are the first-line treatment for AW despite making it difficult to assess encephalopathy. Lorazepam, a short-acting benzodiazepine, is recommended for liver dysfunction (5).

Steroid Utilization

Steroids improve 28-day survival in adults with severe AH but increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and infections (6, 7). The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases has a pathway that uses DF (which involves PT and bilirubin) to determine who is a candidate for steroids and the Lille Model (LM) (which uses age, creatinine, albumin, PT, admission bilirubin, and bilirubin on day 7 of steroids) to assess steroid effectiveness after 7 days (6-8). While DF and LM utilize adult data, in the absence of pediatric studies, we gave our patient steroids for elevated DF. As LM heavily weighs age, it will usually recommend continuing steroids in pediatrics, which may not make sense. We left the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases pathway as we felt steroids were not helping and could increase the risk of decompensation from comorbidities.

Mental Health Support

Depression, GAD, bipolar disorder, and conduct disorder are frequently comorbid with the alcohol-use disorder in adolescents (9). As underlying psychiatric disorders may be masked by alcohol before admission and benzodiazepines during AW treatment, providing interventions and pharmacologic options to aid with sobriety is essential.

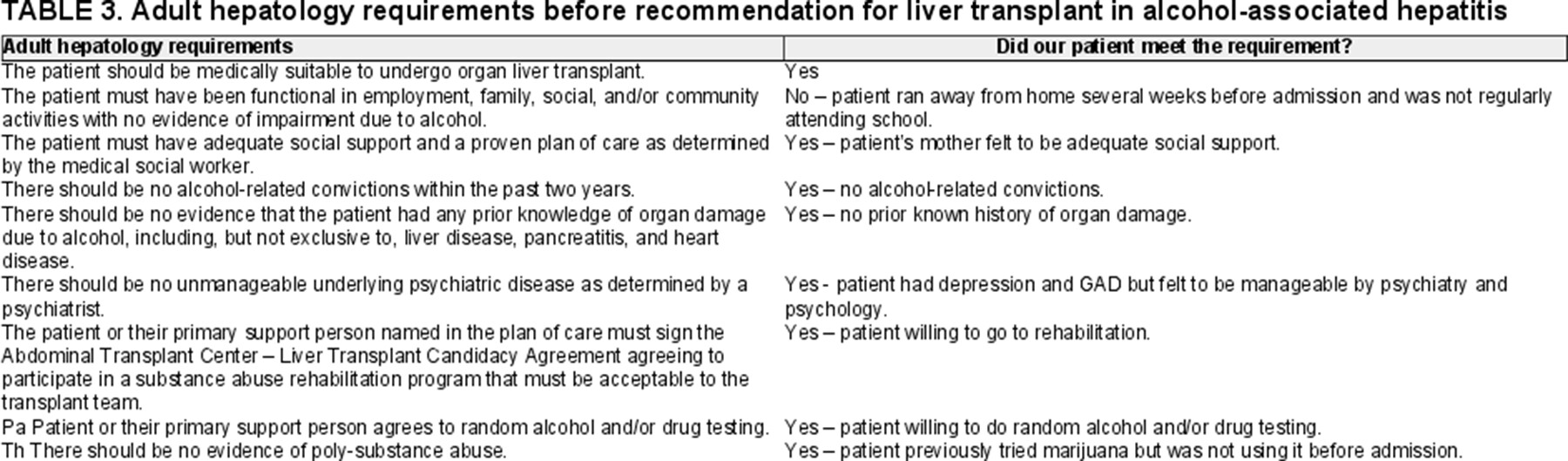

LT Listing

AH is a leading cause of LT in adults (8). In individuals who abstain from alcohol after LT, prognosis is excellent. Historically, LT centers required 6-months of alcohol abstinence before LT listing to ensure patients remained sober and allow for liver recovery. This 6-month sobriety period, which United Network for Organ Sharing does not require, is now controversial as LTs can improve survival in individuals unresponsive to medical therapies (8). Our adult hepatology colleagues have a list of requirements patients with AH must meet to be considered for LT (presented in Table 3). While our patient did not satisfy all requirements, we still recommended LT given his severe presentation and, ultimately, the fact he was a child. He was not listed as insurance required 6-months sobriety before authorization and, as his liver recovered, appeal was not needed. Adult hepatologists frequently appeal LT denials, though are often unsuccessful.

Adult Hepatology Collaboration

Adult hepatologists provided us with a more thorough understanding of severe AH throughout the hospitalization.

CONCLUSION

While severe pediatric AH is previously unheard of because parental supervision, minimal access, and limited finances reduce minor alcohol consumption, binge drinking in adolescents increased during COVID-19 (10). It is possible we may see more severe pediatric AH. We hope our experience aids pediatric AH care while we await further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The patient provided assent and his mother provided consent for the publication of this case report.