Surgical Management of Crohn Disease in Children

Guidelines From the Paediatric IBD Porto Group of ESPGHAN

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jpgn.org).

ESPGHAN is not responsible for the practices of physicians and provides guidelines and position papers as indicators of best practice only. Diagnosis and treatment is at the discretion of physicians.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABSTRACT

The incidence of Crohn disease (CD) has been increasing and surgery needs to be contemplated in a substantial number of cases. The relevant advent of biological treatment has changed but not eliminated the need for surgery in many patients. Despite previous publications on the indications for surgery in CD, there was a need for a comprehensive review of existing evidence on the role of elective surgery and options in pediatric patients affected with CD. We present an expert opinion and critical review of the literature to provide evidence-based guidance to manage these patients. Indications, surgical options, risk factors, and medications in pre- and perioperative period are reviewed in the light of available evidence. Risks and benefits of surgical options are addressed. An algorithm is proposed for the management of postsurgery monitoring, timing for follow-up endoscopy, and treatment options.

INTRODUCTION AND AIMS

The incidence of pediatric Crohn disease (CD), particularly in children 10 to 19 years of age, is increasing and the phenotype is often characterized by extensive inflammation and an aggressive and progressive disease course including growth failure (1.-6.). Despite optimized treatment, almost one-third of the patients will have complications such as fistulae, strictures, and abscesses, undergoing invasive treatment within 5 years of diagnosis (7., 8.). Furthermore, the risk of having surgery is several times higher in children with a long-standing disease than in adults. The risk of surgery at the age of 30 for patients with onset of CD in childhood is 48 ± 5% compared with 14 ± 2% for patients with adult-onset CD (9.).

Surgical procedures in patients with CD can be categorized into 3 major groups: ileocecal resections performed to achieve remission, treatment of complications such as fistulae with or without abscess formation and strictures, and salvage procedures such as subtotal colectomy (eg, proctocolectomy) for severe refractory colitis or small bowel resection for refractory jejuno/ileitis (10.). Urgent surgical procedures related to peritonitis or abdominal abcesses are beyond the scope of this document and will not be addressed.

The most recent pediatric European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO)/European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines provide guidance for medical, but not for surgical treatment of CD (11.). The role of surgery in children with CD, especially with respect to elective resection of medically resistant localized disease, has been addressed in the 1st and the 2nd European evidence-based consensus guidelines (12., 13.). The present report is based on expert opinion and a critical review of the literature and is intended to provide evidence-based guidance for surgical management of pediatric patients with CD, including the role of elective surgery in not only achieving and maintaining remission, but also treating complications and managing pre- and postoperative care. The objectives are to clarify indications as well as delineate risks and benefits of surgery taking into consideration the needs of the individual patient, the natural history of the disease, and currently available alternative medical treatment options.

METHODOLOGY

Selection of the Authors and the Relevant Clinical Topics

The development of these guidelines was initiated at the annual meeting of the ESPGHAN IBD Working Group in Porto in the year 2013, and was followed by an open call to Working Group members. To obtain a balanced position, several other experts joined, including pediatric surgeons. Five major topics were addressed by independent working groups:

- Indications for surgery in pediatric CD

- Consideration for and type of surgery

- Pre- and postoperative care

- Risks associated with surgery as it relates to the natural history of disease

- Surgical management of perianal disease

Literature Search, Grading of the Evidence, Consensus Strategy

The authors of the Working groups performed a systematic literature search using MEDLINE-Pubmed, Embase, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library with the last search date of 2015. Because evidence-based reports on surgical procedures in children with CD are limited, the review included data in adults. The limited pediatric literature precluded the use of the Oxford grading.

Proposed recommendations and practice points were discussed during the 2 face-to-face meetings and anonymous voting. Where the pediatric literature was sparse, recommendations were based on adult data. Controversial issues or recommendations in the absence of relevant pediatric data were resolved by consensus. Final recommendations were accepted when at least 80% agreement was achieved.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SURGERY FOR PEDIATRIC CROHN DISEASE

The natural history of pediatric CD, including need for surgery, is based mainly on cohort studies. Early case series and cohorts from the 1970s and 1980s reflected the lack of effective medications in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to maintain remission (14., 15.).

As a result of the increasing use of immunomodulators and biological anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α agents, such as infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) introduced during the past 15 years to both induce and maintain remission in chronically active CD, the rate of surgical management of pediatric CD may have changed. In pediatric clinical practice, the availability of anti-TNFα agents has differed among regions and countries. These medications approved rapidly in North America (16.) and parts of Europe (eg, Denmark (17.), the Netherlands (18.), and France (19.)) as they were able to use adult data to prescribe them. In the United Kingdom, for example, evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in children (20.-22.) were required before approval was given, and in much of eastern Europe availability of anti-TNF agents to treat children with CD came much later. For these reasons, the natural history is evolving, with systematic reviews showing reduced surgical rates in adult CD with increased use of thiopurines and IFX (23., 24.). In contrast, limited evidence in pediatric CD from either case series or population-based cohort studies suggest lower surgical rates when 25% of patients receive anti-TNFα medications for CD versus earlier periods in the same region when patients were not treated with these medications (19., 25., 26.). The level of exposure to immunomodulators and anti-TNFα agents during the period of assessment is critical in determining its impact on natural history of CD. Finally, when looking for evidence to evaluate the risk of surgical resection or postresection recurrence in children with CD, most information is obtained from series of primarily adult patients that include small numbers of pediatric patients with CD (27., 28.).

As case series of surgery for pediatric CD have been published primarily from single academic centers, rather than population-based cohorts, there is a possibility of bias based upon referral, increased severity of CD, or more access to anti-TNFα therapy (14., 15., 19., 25., 26., 29.-31.). Although longitudinal pediatric CD data from Europe and Canada suggest decreasing rates of CD surgery with time, the reverse has been described in the United States (8., 25., 32., 33.). When pediatric-onset CD was compared with adult-onset CD in the same Scottish population, the rate of surgery at 10 years follow-up and median time to first surgical resection were lower (35% vs 56%) and longer (13.7 vs 7.8 years), respectively (34.). Recent reports show that recurrence rate seems to be high in children: for example, the French Registry of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases incident cohort from Northern France reported CD resection rates of 7% of pediatric patients at 1 year, 20% at 3 years and 34% at 5 years (8.). Further follow-up of the 404 pediatric CD cases diagnosed between 1988 and 2004 in the French Registry of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases cohort noted a recurrence rate of 29% in 140 patients 10 years after their first resection (35.). Smoking, prior resections, perianal disease, penetrating disease behavior and extensive (>50 cm) small bowel resection have been identified as risk factors for postoperative recurrence in mainly adult-onset CD. The relevance of serology and CD genotype are not known, and there are no unequivocal, confirmed risk factors for post-operative recurrence in the current pediatric literature (27.), but stricturing and penetrating CD at diagnosis are associated with an increased risk for a second resection (36.).

CONSIDERATIONS FOR SURGERY IN PEDIATRIC CROHN DISEASE

Definition of a Refractory Crohn Disease Patient

A patient is considered to be refractory to given treatment options when his/her signs and symptoms are caused by CD, relapse during optimized maintenance therapy (immunomodulators, anti-TNFα agents or other biologicals released for pediatric CD) and do not sufficiently respond to induction therapy (corticosteroids, Exclusive Enteral Nutrition—EEN) in spite of being on maintenance therapy. Nonadherence, insufficient therapy, and other causes for the signs and symptoms should be excluded before surgery is considered.

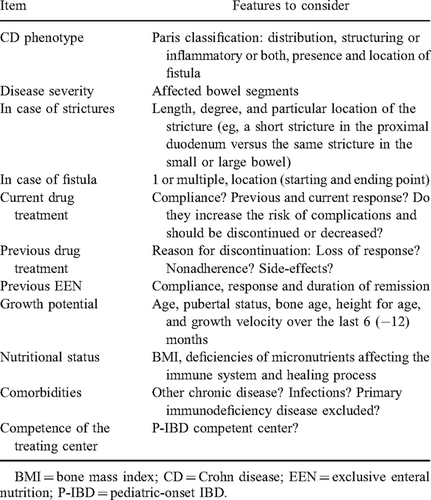

It is mandatory to prove with a high degree of certainty that signs and symptoms are due to active CD and not due to other causes (eg, diarrhea due to bile salt loss or infection, abdominal pain due to functional disorders or depression, growth failure due to growth hormone or nutritional deficiencies). Alternatively, if a specific bowel segment is responsible for symptoms, surgical intervention may be more appropriate than continued medical treatment. Nonadherence, inadequate dosing, or duration of medical therapy must be considered, before the patient is deemed to be refractory to therapy. Some relevant issues that should be considered before surgical intervention are shown in Table 1.

The decision for or against elective surgery in a patient with refractory CD rests on the short-term and long-term risks and benefits, such as the extent of disease and likelihood of remission or recurrence with resection. The decision is highly individualized.

Surgical resection is not curative for CD. Relapse, both at the area of anastomosis and at other sites, frequently occurs within 5 years postsurgery (31., 37., 38.). Refractory disease implies that the defined treatment goal for this patient cannot be achieved with the nonsurgical treatment option(s) and/or that continued medical management may have higher short-term or long-term risks than surgery. One must also take into account the relative costs and potential toxicities of long-term medical therapy. Treatment goals differ from patient to patient and should be well defined when a surgical procedure is considered. They include improvement of signs and symptoms severely affecting the quality of life (eg, pain, diarrhea, obstruction, fecal incontinence, growth failure) or prevention of severe complications (eg, ileus in bowel occlusion, fistula, abscess formation).

Indications for Surgery

Statement 1. Surgery may be considered as an alternative to medical therapy when a patient has active disease limited to a short segment(s) despite optimized medical treatment. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 2. Surgery should be considered in children in prepubertal or pubertal stage if growth velocity for bone age is reduced over a period of 6 to 12 months in spite of optimized medical and nutritional therapy. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- In the absence of refractory disease, elective surgery is usually not indicated.

- In prepubertal or pubertal children with a delay in bone age, resection of a localized disease segment that is resistant to conservative therapy, may lead to catch-up growth within the next 6 months of postoperative period.

Growth failure is more frequent in CD than in ulcerative colitis (UC) being present in 15% to 40% of pediatric CD patients (39., 40.). Although the use of corticosteroids has been implicated in growth failure, uncontrolled disease activity is considered the major factor. One of the main contributors to growth impairment is malnutrition influenced by enteric losses with malabsorption, suboptimal intake and increased energy needs (41.). Moreover, increased cytokine production [eg, interleukine (IL)-1β, IL-6, TNFα], impairs hepatic expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 and contributes to growth hormone resistance in chondrocytes. Growth failure, characterized by delayed skeletal maturation and delayed onset of puberty, is best described in terms of height-for-age standard deviation score (z score) or by variations in growth velocity for a period of 6 to 12 months. Earlier literature described the role of surgery in promoting growth in CD pediatric patients (42., 43.). Most of these studies, however, were performed before the era of biological agents and may have been impacted by the increased use of corticosteroids.

Three retrospective trials with growth as an outcome measure were identified. One of these evaluated the effect of surgery on growth in children with CD who did not respond to medical therapy (30.). Growth and nutritional status improved by 6 and 12 months after surgery, with a significant increase in weight and height z scores. The other 2 studies analyzed the postoperative course of pediatric CD and the predictive factors of early postoperative recurrence (44., 45.). After surgery, a significant improvement occurred in z scores for height and a mean height velocity of patients increased from 2.3 cm/y preoperatively to 3.4 cm/y following surgery. These results were supported by other studies (46.-49.). Moreover, delaying surgical intervention into the late stages of puberty results in poor catch-up growth (39.).

Furthermore, concerns about inadequate growth and the prospect of not achieving adult growth potential may impact the quality of life for some patients. For these reasons, surgery should be considered a therapeutic strategy for inducing remission in early or mid-puberty in a child with localized CD who is refractory to medical therapies. Refusal, intolerance, or increased risks of maintenance medications such as immunomodulators or anti-TNFα agents may also be considered as possible indications for elective surgery.

Investigations Required Before Surgery

Statement 3. A complete assessment of the patient's general and bowel condition is recommended before elective surgery to optimize the surgical approach, minimize the length of bowel resection, and reduce the risk of complications. It should include history, physical examination, ileocolonoscopy, imaging studies, screening for concomitant infections, and nutritional deficiencies. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- The optimal timing of surgery, the approach (laparoscopic or open) and bowel segments to be addressed should be discussed among the pediatric gastroenterologist, pediatric (or adult) surgeon, patient, and parents.

- It is preferable that ileocolonoscopy (eosophagogastroduodenoscopy being optional depending on the actual disease) and imaging studies are performed in the center where the surgery will be performed.

- The nutritional status should be assessed by anthropometry, laboratory parameters such as albumin, iron status, and selected vitamins and trace elements, depending on the individual patient.

- In severe cases an extensive workup for immunodeficiency disorders should be completed in a specialized center before surgery.

SELECTION OF THE TYPE OF SURGERY

Statement 4. Limited resection should be performed when a patient has localized small bowel or colonic CD not responsive to medical therapy. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 5. Stricturoplasty needs to be considered when a symptomatic patient has multiple short strictures in the small bowel. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 6. Extensive resections of the small bowel should be avoided as they pose a long-term risk of development of short-bowel syndrome. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 7. When a patient has pancolonic disease the choice of surgery is subtotal colectomy and ileostomy. Later ileorectal anastomosis can be performed if rectum is spared and there is no significant perianal disease. One stage ileo-rectal anastomosis is generally not advised. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 8. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is not recommended when a patient has CD. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- Limited resections are especially relevant for ileocecal lesions.

- Although stoma is recommended as a general rule, partial colectomy and ileo-rectal anastomosis may be performed without diverting ileostomy as a primary procedure in patients without significant immunosuppression or malnutrition. Increased rates of leakage associated with ileo-rectal anastomoses, however, support the use of temporary diverting ileostomy (44).

- Reversal of the diverting ileostomy following colonic resection may result in recurrence of inflammation in the colon or rectum.

- Patients requiring emergent colectomy are not candidates for immediate reconstruction and should undergo a 2- or 3-staged procedure.

- Although not recommended as a standard procedure, ileal pouch anal anastomosis may be considered in highly selected cases, that is, these patients need to be highly motivated and have no perianal or small bowel disease and good sphincter function. Successful outcomes can be achieved with this procedure.

- Patients and their families should be aware of all possible risks and high complication rate including anastomotic leaks, anastomotic strictures, fistula formation to the anastomosis, as well as the risk of recurrence. Significant time should be dedicated to patients and their families during the counseling before the surgical procedure to discuss the possible complications and functional impairment.

Limited Small Bowel Disease

For single site disease, such as the ileocecal area, a limited resection may be the treatment of choice. Reports of isolated small bowel resection surgery can be found in many of the larger published pediatric surgical series (1 case each described by Romeo et al (50.), Simon et al (51.) and 2 cases each by Ba'ath (52.), Blackburn et al (31.), 11 cases by Hansen et al (38.), 16 cases by Diamond et al (29.)). There is considerable debate in the literature whether surgery for CD should be performed laparoscopically or through the conventional open technique (53.-55.). The laparoscopic surgical approaches, however, can certainly be used safely in children with low complication rates (29., 55.-57.).

For single and multiple site disease, stricturoplasty is best undertaken to preserve bowel length. Stricturoplasty has the advantage of bowel preservation, whereas surgical resection may put the patient at risk for short bowel. There does not appear to be a significant difference between the outcomes or the complication rates between surgical resection or stricturoplasty in pediatric CD (50.).

Standard Heinecke-Miculicz stricturoplasty is suitable for short segment strictures. Finney type stricturoplasty is used for strictures up to 20 cm long. For longer than 20 cm strictures, either a specialized form of stricturoplasty or a combination of resection and stricturoplasty type with anastomosis may be used.

Colonic Crohn Disease

Symptoms of colitis are typically the first manifestations of CD in children under the age of 8 years (58., 59.). The distribution of the disease may change with age making the choice of most appropriate surgery more difficult (59.). There is a lack of reliable pediatric data related to the management of Crohn colitis.

The main problem in the choice of operative treatment for colonic CD is the expected high rate of disease relapse (37., 44.). Due to the high incidence of complications and relapses, risk of pediatric patients with colonic disease to end up with permanent ileostomy has been considerable. Recent reports in adults suggest that bowel sparing surgery in the form of segmental resections has better long-term outcomes (60., 61.). Segmental large bowel resections have also been performed in children with left-sided colitis (62.) but recent data in 81 patients suggested that most patients will eventually require subsequent colectomy (Ian Sugarman, personal communication). Harper showed that temporary ileostomy is a safe conservative procedure which enables improvement in severely ill and even malnourished patients with Crohn colitis (63.). When a subsequent resection becomes necessary, it may be less extensive than initially considered because of the healing that has occurred due to improved nutrition (64.). Long-term remission is more common in patients with no significant anorectal disease (65.). Female gender and history of perianal disease have been reported to be predictive of repeat resection (61.). An important technical detail is to perform a wide bowel anastomosis, preferably with a stapled functional end-to-end technique that is associated with longer recurrence-free periods when compared with hand sewn anastomoses (66.).

In children with refractory pan-colonic disease the choice of operation is usually total colectomy and ileo-rectal anastomosis. Elective resection with a primary anastomosis may be considered in a stable patient with good nutritional status. In the case of an emergency the best choice is, however, usually a staged procedure. Patients undergoing ileo-rectal anastomosis have excellent chances to avoid protectomy and permanent stoma formation. Preservation of the ileo-rectal anastomosis despite frequent recurrences of active disease has been reported in 76% to 86% of the cases (67., 68.). Active anorectal disease at the time of the anastomosis is the best predictor for failure of the anastomosis (68.).

An alternative for total colectomy and ileo-rectal anastomosis is ileal pouch-rectal anastomosis. This may be considered in cases in which only a short segment of the rectum is retained following resection of diseased large bowel. A short ileal pouch (8–10 cm) is anastomosed with the rectal stump. The outcomes after ileal pouch-rectal anastomosis are similar to those after ileo-rectal anastomosis (69.).

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is generally thought to be contraindicated in CD (70.). This is based on data from patients having undergone ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for presumed UC who subsequently had a change of diagnosis to CD. The cumulative frequencies of CD of the ileo-anal pouch originally devised for UC has ranged between 3% and 13% (71.). The diagnosis of CD of the pouch has been associated with 5-fold increase in risk of pouch failure compared with patients with ileo-anal pouch without CD (72., 73.).

There is, however, recent growing evidence that supports highly selective use of restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for CD. These patients have isolated colonic CD and no evidence of ileal or perianal involvement.

In patients with severe rectal and perianal disease, proctectomy or enteric diversion are rarely indicated, see section of Perianal disease. Colonic stricturoplasties, although feasible, are associated with a higher risk of complications and are therefore seldom used.

RISK FACTORS OF COMPLICATIONS OF SURGERY AND PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Immediate Postoperative Complications

Statement 9. Corticosteroids exposure should be minimized prior surgery to reduce surgery-related complications such as infections. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 10. Anti-TNFα administration during immediate perioperative period (see practice point) is discouraged, as it is associated with an increased risk of infection. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 11. Nutritional status should be optimized and anemia corrected to reduce the risk of postoperative complications. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 12. A patient should cease smoking before surgery given the strong association of smoking with postoperative recurrence. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- Risk factors of perioperative complications include poor nutritional status, anemia, cigarette smoking and perioperative corticosteroid or anti-TNFα treatment.

- Immediate postoperative morbidity ranges from 20% to 30%, in small bowel or ileocolic resection to 50% to 60%, in subtotal colectomy (29,74,75).

- Whenever possible, it is recommended to discontinue corticosteroids before surgery or to lower the dose to at least 0.5 mg/kg or 20 mg, whatever is less to minimize the risk of complications.

- It is advisable to avoid anti-TNF drugs during the perioperative period (optimally 4–6 weeks before and in high-risk patients continuing anti-TNF postoperatively 1–3 weeks following surgery to minimize the risk of complications and in the latter group the risk of development of drug antibodies).

- Data on the impact of immunomodulators to the risk of immediate postoperative complications is limited and conflicting. Although immunomodulators may be used throughout the perioperative period if maintenance therapy is indicated postoperatively, it may be reasonable to discontinue treatment with immunomodulators at least 1 week before surgery to reduce the risk for infections.

- Stress doses of corticosteroids should be administered if steroids are ongoing or discontinued close to the time of the surgery, or adrenal suppression is not excluded.

- Nutritional status should be optimized before surgery by using enteral nutrition (EN), but for some patients TPN may be needed.

- Bowel cleansing is performed at discretion of the surgeon but not routinely required.

- Although infrequent, the presence of hyperglycemia should be excluded, as it is associated with poorer outcomes, including poor wound healing and increased risk of infection.

- Hospitalized children with CD should be assessed for potential risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) including disease activity, steroid use, central venous access, parenteral nutrition, hypercoagulable condition, and immobilization. VTE prevention such as hydration, compression stockings, and mobilization should be provided to all patients. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis may be considered in the postoperative course, although the absolute risk of VTE in children appears lower than in adults.

- If indicated by family history, common genetic mutations associated with an increased risk of VTE should be screened preoperatively.

The most common short-term postoperative complications of bowel surgery are anastomotic leak, small bowel obstruction and ileus, infections, need for ileostomy, wound complications, fistulas, gastrointestinal bleeding, and VTE. Complication rates seem to be slightly lower in children than in adults, but vary a lot between procedures and studies (31., 76.-78.). Cigarette smoking is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications in adults (odds ratio [OR] = 1.24 (1.09–1.41) with CD (79.). Anemia and weight loss before surgery are also associated with a worse prognosis (79.). Blackburn et al (31.) recently reported their 10-year pediatric experience on risk of complications at a regional pediatric gastroenterology center. Among the 62 patients, there were 13 (22%) early and 5 (8.6%) late complications following intra-abdominal surgery. Piekkala et al (37.) reported their long-term surgical outcomes in 36 Finnish children. At least 1 surgical complication occurred in 77% of patients. In a recent study, the postoperative complication rate was significantly lower in patients who had an ileal 1/16 (6%) or ileo-cecal resection 13/54 (24%) compared with hemi- 5/12 (42%) or total colectomy 11/21 (52%). In this report 10% to 30% of patients required further intervention mainly for ileus, bleeding, and infection (38.).

In children, the absolute risk of VTE is lower than in adults (80., 81.). The absolute risks for VTE among children with CD with and without surgery were calculated to be 111.2 and 121.2/10,000 hospitalizations, respectively (80.). There are no published trials for the efficacy and safety of thromboprophylaxis in children with CD, but a guideline for evaluation of risk and prophylactic options has been proposed (82.).

Perioperative Medication

Corticosteroids

In adults, most publications have reported a negative impact of the preoperative use of ≥5 mg prednisone (or its equivalent) daily within 14 to 60 days before surgery or ≥10 mg prednisone (or its equivalent) for at least 4 weeks before surgery (83., 84.). In their prospective follow-up study, Nguyen et al (85.) reported an excess of complications, but not mortality, in patients with corticosteroid use within 30 days before surgery (adjusted OR (95% confidence interval [CI]) = 1.26 (1.12–1.41) for CD. In the long-term registry of North American patients with Crohn Disease (TREAT) registry glucocorticoid use was an independent risk factor of serious infections (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.46–3.34) (86., 87.). In addition to the septic concerns, steroid use can lead to the suppression of the hypothalamus-pituitary-axis and subsequent adrenal insufficiency, even after shorter periods of therapy (84., 88., 89.). For this reason, perioperative glucocorticoid replacement therapy may be required. Wound healing complications, such as, disruption, persistent drainage, dehiscence, or wound failure, are usually associated with chronic use of corticosteroids at high doses (90.).

5 Aminosalicylates

There is a paucity of clinical data for perioperative use of 5 aminosalicylates (5-ASA). Kumar et al (91.) suggested to discontinue the drug on the day of surgery. Continuing drugs after surgery is specific to each patient.

Immunomodulators

There are conflicting reports about the use of immunomodulators preoperatively and most data comes from adult studies (84.). In a retrospective study of 159 CD patients undergoing bowel surgery, Aberra et al (92.) found no increased infectious risk among patients receiving corticosteroids alone or patients receiving thiopurines with or without corticosteroids, in comparison to patients receiving neither medications. Additional reports including >200 adult patients each identified no increased risk of complications with immunosuppressive therapy at surgery (93., 94.). Tay et al (95.) reported a lower incidence of septic complications in patients receiving immunomodulators (5.6% vs 25%). In contrast, another study found that thiopurines were associated with an increased risk of intra-abdominal septic complications (16% vs 6% without therapy) (96.).

Existing data do not suggest a significantly increased risk of perioperative infections or impaired wound healing with methotrexate. Given the lack of data, it may be reasonable to discontinue methotrexate at least 1 week before surgery in patients with a history of previous or severe septic complications, and resume if necessary no sooner than 1 week after surgery or when the wound has healed (97.).

Biologics

There are conflicting results whether preoperative use of biologics increases risk of infectious complications (84.). There are only limited data in children (98.). A meta-analysis of the preoperative use of anti-TNF therapy in adults showed an increased prevalence of postoperative complications (OR = 1.45, 95% CI 1.04–2.02; 13 studies, 2538 patients), as well as for both infectious (OR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.08–1.99; 10 studies, 2116 patients) and noninfectious complications (OR = 2.29, 95% CI 1.14–4.61; 3 studies, 729 patients) (99.). All included studies are retrospective, patient groups are heterogeneous, the inclusion criteria and definitions of complications vary, and confounding effects of concomitant therapies are not defined. Patients treated with IFX were more likely to be treated with immunomodulators and steroids. Also, the patients usually had additional risk factors including adverse surgical outcomes, malnutrition, and urgent indications for an operation.

Preoperative Nutrition

Practice point:

- Consider initiation of EEN (continuous or bolus if tolerated) for at least 2 weeks before imaging studies and surgery are performed. Attenuation of inflammation will improve distinction between bowel narrowing due to stricturing or inflammatory processes (100). This will allow the surgeon to plan the best approach (stricturoplasty or resection and minimize bowel loss). EEN will also allow reduction of corticosteroids, if given, and improvement of nutritional status.

Enteral support whenever possible is preferable to TPN to improve nutritional status because it is physiologic, is less costly, and has less potential for sepsis. A number of studies reported that poor nutritional status at the time of operation significantly increased the risk of postoperative complications and intra-abdominal infections in CD (101.-104.). Intra-abdominal septic complications were associated with hypoalbuminemia <3.0 g/dL (101.) and the complication rate was 29% among 124 patients with low serum albumin levels (<3.1 g/dL) but only 6% among patients with normal albumin levels (104.). Improvement of nutritional status by TPN may contribute to a reduction of postoperative complications in both adult and pediatric patients (103., 105., 106.). Anastomotic dehiscence is consistently associated with a serum albumin levels <3.5 g/dL in elective colorectal resections in adults (for review (84.)). In a study of 78 patients with penetrating CD, preoperative management, including nutritional support and weaning off steroids, allowed ileocecal resection with low rates of postoperative morbidity (107.).

LONG-TERM POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Statement 13. Vitamin B12 levels (active vitamin B12) should be routinely monitored in patients who undergo resection of >20 cm of terminal ileum. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 14. Bile acid malabsorption should be suspected in patients with persistent diarrhea despite clinical remission or limited disease activity after ileal resection. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 15. The patient should be informed that after surgical resection, the risk of bowel obstruction is increased (either secondary to recurrent disease or adhesions). (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- The risk of postsurgical functional impairment, although small, should be discussed before patients undergo intestinal resection. Bowel function is not often affected by localized small bowel or ileocecal resection. Subtotal colectomy and ileoanal anastomosis result in an increased frequency of defecation, but the functional outcome is good when CD stays in remission.

- Ileal resection <20 cm of bowel length is infrequently associated with vitamin B12 deficiency or bile acid malabsorption. Surgical treatment should aim to preserve bowel length by using bowel sparing techniques.

- Methylmalonic acid may help in detecting early vitamin B12 deficiency (by itself or with a homocysteine test).

- As stated in the “Selection of the type of surgery” section, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis should be avoided in CD. Repeated episodes of pouchitis are common and pouch failure may occur in CD patients with a pouch.

- There is limited evidence that fertility may be lower in patients with CD and this may be further enhanced by surgery (108,109).

Bowel Function

There are limited data on postsurgical bowel function. Only 1 study with a small number of patients addressed the development of functional problems after small intestinal resection. Almost all children with limited ileal resection were continent, as were children with partial colectomy but this was based on only 6 children (37.). Meta-analysis that compared segmental versus subtotal/total colectomy in adults found that more patients were continent after segmental colectomy (110.). There are no pediatric data regarding bowel function after ileo-rectal anastomosis.

The only large study reporting functional outcomes after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) in the pediatric population included 433 patients (5.1% with UC patients postoperatively classified as CD) (111.). Wound infection and pouch failure rates were significantly higher in patients with CD. Piekkala et al (37.) reported a small pediatric study in which all patients with IPAA had experienced pouchitis and eventually, 4 of 8 patients needed bowel diversion. The latter study is the only study addressing the development of functional problems after small bowel resection but the study is retrospective with small number of patients. In adult patients functional results after IPAA are inconsistent and meta-analysis found no significant functional differences between CD and UC patients except for increased urgency and incontinence in CD patients (112.-116.). Other studies in adults reported that patients with proven CD who underwent IPAA developed CD of the pouch in 40% to 63% of cases during the 5-year postoperative period (117., 118.).

Vitamin B12 Malabsorption

Resection of the terminal ileum may lead to malabsorption of vitamin B12. Ahmed and Jenkins (119.) reported the effect of small bowel surgery on vitamin B12 levels in 18 children with variable ileal resection due to CD for a period of 10 years. None of the children had low vitamin B12 levels before or after small bowel surgery suggesting that serum levels are poor indicators for actual needs. Recently, measurement of active vitamin B12 (transcobalamin-bound) has been adopted (120.). A recently published systematic review in adults with IBD found that ileal resections greater than 30 cm were associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, whereas those patients with <20 cm of resected ileum had normal serum vitamin B12 (121.).

Bile Acid Malabsorption

Approximately 95% of bile acids are re-absorbed in the distal ileum and although their malabsorption can cause diarrhea, it is unusual to have steatorrhea with malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins resulting in the formation of gallstones and kidney stones (122., 123.). One pediatric study found that 23% of patients with CD had bile acid malabsorption (124.). Patients with previous ileal resections (resected bowel length was 10–30 cm) had significantly higher serum C4-concentrations (7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one), suggesting bile acid malabsorption, than patients with ileal inflammation only (124.). Adult studies showed bile acid malabsorption in 55% to 90% of patients who had terminal ileal resections (125.-127.).

Resection of the terminal ileum may lead to diarrhea due to bile acid malabsorption. When suspected, bile acid malabsorption may be confirmed indirectly by a short-term empirical treatment with bile acid-binding drugs, such as cholestyramine or colestipol. Measurement of serum 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one levels in serum may be helpful to establish a diagnosis when available (128.). Measurement of whole body retention of a radioactive bile acid, SeHCAT (selenium-75-homocholic acid taurine) is not standardized.

Quality of Life After Crohn Disease Surgery

The quality of life (QoL) is in general good after CD surgery at pediatric age. Piekkala et al (37.) found comparable QoL between the patients and controls, but when patients had school or work absences the QoL decreased. The type of surgery or the number of complications did not appear to have an effect on QoL. Two studies from the same center, performed on limited number of patients (n = 5 in both studies) reported that stoma formation was associated with restricted sport activities in children (129., 130.). On the other hand, Piekkala found no effect of permanent stoma on QoL in children compared to adult patients with a stoma who scored lower for general health and physical activity compared to controls (37., 131.).

Intestinal Obstruction

One of the late complications of surgery in CD patients is intestinal obstruction. Pediatric data showed that the incidence of bowel obstruction caused by adhesions or anastomotic stricture varied from 1.2% to 9.1% for the first 12 to 24 months after the surgery (29., 31., 53., 132.). Only 1 study reported bowel obstruction due to adhesions in 12/36 (33.3%) and anastomotic stenosis/stricture in 9/36 (25%) of patients with a median follow-up of 10 years (37.).

Strong evidence does not exist linking specific surgically related factors to the postoperative development of intestinal obstruction. A pediatric study found a higher risk to re-stricture following strictureplasty compared with resection (133.); however, data are not uniform (50.). Another proposed risk factor is end-to-end anastomosis, but a meta-analysis of adult data found that end-to-end anastomosis is not associated with an increased risk for obstruction (134., 135.). One RCT in adults found that open surgery is more likely to cause obstruction compared with laparoscopic procedure, whereas another found no advantages of laparoscopic procedure over open surgery (136., 137.).

Short Bowel Syndrome/Intestinal Failure

Studies in adults found that the cumulative incidence for intestinal failure in CD is 1% after 5 years and 4.5% to 6.1% after 15 years from initial surgery (138., 139.). Identified risk factors include penetrating disease type, remaining small intestine of <200 cm, ostomy creation and colectomy (140.). Based on these observations, surgical treatment should preserve bowel length as much as possible by using bowel sparing techniques, including strictureplasty and limiting removal of the bowel to those areas associated with the symptoms (141., 142.).

Fertility

Abdominal surgery in patients with severe inflammation may be associated with impaired fertility, whereas in less ill patients fertility is preserved as recently shown in a large cohort of women undergoing surgery for appendicitis (143.). There are no studies on pediatric CD.

SCHEDULE FOR FOLLOW-UP AFTER SURGERY

Statement 16. Postoperative medical treatment should be based on ileocolonoscopy assessment and not solely on symptoms or serum inflammatory markers. Repeated fecal biomarkers testing may aid in deciding on the timing of endoscopy. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- Postoperative endoscopic evaluation should be performed at 6 to 9 months after surgery (144,145).

- Local recurrence limited to the anastomotic site (Rutgeerts i1), however, is common but does not indicate need for changing therapy in asymptomatic patients.

- Fecal calprotectin is superior to C-reactive protein (CRP) and clinical disease activity indices in monitoring disease recurrence. It is advisable to test calprotectin level repeatedly during the follow-up to detect early asymptomatic recurrence. The scheme for most effective follow-up is not established but testing at least 2 to 3 times per year is advisable.

- Magnetic resonance enterography, abdominal ultrasound, and wireless capsule endoscopy can detect disease recurrence but are not a substitute for endoscopy.

Predictors of Early Recurrence

There are no pediatric studies identifying predictors of early recurrence after surgical resection in CD but the risk is high (27., 35., 37., 38.). In adults, there are recognized as risk factors for recurrence, such as smoking, penetrating disease, perianal disease, presence of granuloma in the resected segments, submucosal plexitis, or presence of extraintestinal manifestations (146.).

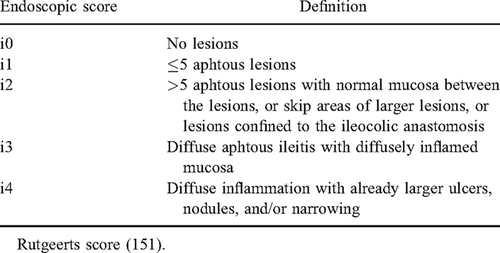

Although clinical recurrence occurs in 30% during the first year after resection, approximately 80% show endoscopic recurrence that precedes clinical symptoms (147.). Therefore, endoscopic recurrence is the strongest predictor of disease progression (148.-151.). Rutgeerts index is the most widely used measure to assess endoscopic lesions and has a strong predictive validity in adults (Table 2) (151., 152.). Rutgeerts score ≥ i2 has higher risk of clinical recurrence at 4 years compared with score <i2 (100% vs 9%, respectively) (151.).

Monitoring to detect recurrence is important. Because publications dealing with this issue are almost all based on adult patients, pediatric recommendations have to be extrapolated. The recently published Australian randomized postoperative Crohn endoscopic recurrence trial (POCER) study evaluated the efficacy of endoscopically tailored treatment (153.). A cohort of 174 adult CD patients was included and all received medical prophylaxis starting immediately after surgery. After randomization (2:1) further step-up in treatment was based upon findings at ileocolonoscopy at 6 months (endoscopy group) or clinical symptoms (control group). Ileocolonoscopy performed 18 months after surgery showed recurrence in 49% in the endoscopy group versus 67% (P = 0.03) in the control group. Therefore, ileocolonoscopy performed 6 months after resection is recommended to monitor for postoperative recurrence (154.). There is poor correlation between postoperative endoscopic recurrence and clinical symptoms, Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) or blood inflammatory markers such as CRP (12., 27., 147., 155.).

Fecal calprotectin may be used to screen patients who require colonoscopy for detecting mucosal recurrence and may be helpful in the timing of endoscopy (156., 157.). This is supported by data from the POCER study, which shows that the level of calprotectin correlates well with endoscopic recurrence but not with CRP or CDAI (153., 158., 159.). Level of calprotectin >100 μg/g indicated endoscopic recurrence with a sensitivity 0.89 and negative predictive value 0.91. This means that colonoscopy could have been avoided in 47% of patients. Another adult study reported accordingly that the best cutoff point for calprotectin was 100 μg/g to distinguish between endoscopic remission and recurrence, with a sensitivity 0.95 and negative predictive value 0.93 (160.). Such levels are, however, close to normal values, and therefore the level of calprotectin that practically should lead to endoscopy remains to be determined. There are no pediatric data yet on the strategy of follow-up after surgery. A small pediatric study reported that when compared with first postoperative fecal calprotectin, the concentration of calprotectin increased significantly more in patients with either endoscopic or histological recurrence versus no recurrence. The best cutoffs in pediatric patients were as follows: calprotectin >139 μg/g or increase of 79 μg/g compared with first postoperative value were suggestive of endoscopic recurrence (Rutgeerts score i2–i4), while calprotectin >101 μg/g or increase of 21 μg/g indicated histological recurrence (161.). It must be, however, noted that exact levels of calprotectin may differ with specific brands; therefore, reference values must be determined locally according to the method used.

Abdominal US and CT can also be used for detection of disease recurrence, but because of radiation CT should be avoided in children, if possible (162.). One study found magnetic resonance enterography to have a similar value in predicting postoperative recurrence as ileocolonoscopy (163.). A number of small studies with conflicting data show that wireless capsule endoscopy may be used in detecting mucosal lesions post-surgery in selected patients (156.-158.). Presently none of these studies have, however, proven to be superior to ileocolonoscopy for disease sited within the reach of ileocolonoscopy. In patients with lesions of the small bowel then magnetic resonance enterography is more appropriate.

PREVENTION OF RECURRENCE

The risk of recurrence depends on several factors. Patients with extensive disease, short disease duration from diagnosis to surgery, recurrent surgery, long resected segment, surgery for fistulizing disease, disease complications, impaired growth, pubertal delay, perianal disease, or smoking habits may be categorized as having high risk and therefore need a more active follow-up.

Thiopurines

Statement 17. 1. Thiopurines may be used for preventing postoperative recurrence when a child has a moderate risk of CD recurrence. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 18. 2. When thiopurines have failed preoperatively their postoperative use requires careful risk-benefit analysis. (Agreement 100%)

Practice point:

- Thiopurines should be considered after surgery in thiopurine-naïve patients with extensive disease or risk factors of relapse. When preoperatively adequately treated with thiopurines and disease activity results in surgery, the efficacy of using thiopurines in preventing recurrence is uncertain as most of the reported data of the postoperative efficacy come from patients previously treatement naïve. In patients pretreated with thiopurines, relapse prevention with methotrexate may be an option, but there are no specific data available.

Thiopurines (azathioprine [AZA] and 6-mercaptopurine [6MP]) have a well-established role in maintaining remission in CD. Their efficacy in preventing postoperative recurrence is debated and all data come from adult studies (164.-166.). The ECCO 2010 guideline advocates their use postoperatively in patients with “high-risk” factors (13.). Thiopurines were superior over 5-ASA in preventing any endoscopic recurrence at 12 months but not severe recurrence, and not clinical recurrence at 12 or 24 months (167.-170.). Combining the only studies with a placebo arm, however, demonstrated that the use of thiopurine reduced clinical and severe endoscopic recurrence at 12 months (169., 171.). The superiority of thiopurine over 5-ASA was shown in a third meta-analysis, although thiopurines were associated with more adverse events (172., 173.). In the RCTs, most patients randomized to receive AZA/6-MP were thiopurine-naïve (previous thiopurine exposure in 7% in the D'Haens’ study, 8.5% in the Ardizzone study, not specified in the Hanauer study) (169., 171., 174.). There is no evidence-based data on the use of MTX in preventing postoperative recurrence in pediatric CD.

Biologics

Statement 19. 1. Treatment with anti-TNFα is recommended when a CD patient has a high risk of postoperative recurrence or has widespread disease. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 20. 2. When a patient experiences endoscopic recurrence after intestinal resection despite optimal thiopurine treatment, the therapy should be escalated to anti-TNFα medication. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- Anti-TNFα treatment may be used postoperatively if the patient has been a primary responder, did not develop anti-TNF antibodies and also in those with widespread disease, that is, active disease beyond the resected site.

- Those with reintroduction of anti-TNFα after an interval of >12 weeks need careful monitoring for development of antibody-associated loss of response.

- Early endoscopic evaluation after surgery (suggested 6 months) has been shown to be adequate to help decide when to introduce anti-TNFα in patients without apparent disease after surgery (153).

Evidence for prophylactic anti-TNFα use in postoperative recurrence is based on several small clinical trials in adults summarized in Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A936. The most recent RCT study, POCER study, concluded that selective immune suppression, adjusted for early recurrence, rather than routine use, leads to disease control in most patients (153.).

Most of the adult studies cited did not include patients previously treated with anti-TNFα. In the randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study on anti-TNFα in postoperative CD, there were only 8 patients who had received prior IFX (30% in the IFX group) within 6 months of surgery (number of infusions 1–4) (155.). Patients with fibrostenosis or penetrating disease were not considered true primary nonresponders, but rather had developed complications that required surgery. In the POCER study no more than one-third of the studied patients had previously received anti-TNFα (21% and 29% of the active care and the standard care groups, respectively) (153.). Therefore, there is insufficient data to establish if anti-TNFα agents are less effective in preventing recurrence if prescribed for the patient who failed treatment before the surgery as compared to the anti-TNFα-naïve patient. Also, the presence of drug antibodies underlying loss of response is less reported. The use of IFX reduced the rate of endoscopic but not clinical recurrence (175.).

One study reported benefit from lower doses of anti-TNFα (IFX 3 mg/kg) to maintain remission but trough levels were not measured (176.). Thus, this approach is not recommended in pediatric patients.

Other Medications

Practice point:

- The evidence is weak to support the use of the following post-operative prevention medications: 5-ASA/sulfasalazine, budesonide, antibiotics, and probiotics.

There are no pediatric studies evaluating these medications. Trials of mesalazine therapy (3–4 g/day) showed a significant reduction of risk of clinical (relative risk [RR] 0.76, 95% CI 0.62–0.94) and severe endoscopic recurrence (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.38–0.92) in adults but the number needed to treat for these outcomes was high (12 and 7, respectively) (169., 177.-181.). Also, nitroimidazole antibiotics (eg, metronidazole) have been used to prevent relapse, but they may not produce added benefit when used as concomitant therapy with AZA (182.). Adverse effects may limit long-term use in children. A Cochrane review, which evaluated 2 adult trials, concluded that the risk of clinical and endoscopic recurrence was reduced with nitroimidazole antibiotics compared with placebo (RR 0.23, 95% 0.09–0.57, number needed to treat = 4 and RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26–0.74, number needed to treat = 4) (164., 183., 184.). In 1 trial metronidazole was administered for 3 months and in the other, ornidazole for 1 year. Results for ciprofloxacin (500 mg bid for 6 months vs placebo) have been disappointing in a recent pilot RCT (185.). Budesonide and probiotics are ineffective in relapse prevention (186.-191.).

Partial EN may be an effective treatment option to prevent postoperative recurrence based on a nonrandomized prospective study in 40 adult CD patients with ileal or ileocolonic resection (192.). In the EN group, 1 of 20 patients developed clinical recurrence compared with 7 of 20 in the non-EN group during 1-year follow-up (endoscopic recurrence rates were 30% vs 70%, respectively). EN consisted of nocturnal infusion of elemental diet (via nasogastric tube) along a low-fat diet during the day for 12 months, compared with no nutritional intervention (non-EN group). All of the patients received 5-ASA medication. The treatment acceptability was low (50%). The beneficial effect of EN in preventing postoperative recurrence following resection was further supported by a 5-year follow-up study (193.). Another nonrandomized study from Japan suggested a benefit in preventing postoperative recurrence from taking >50% of calories in the form of EN (194.). No pediatric trial to date has evaluated the potential or efficacy of postoperative EN in preventing recurrence.

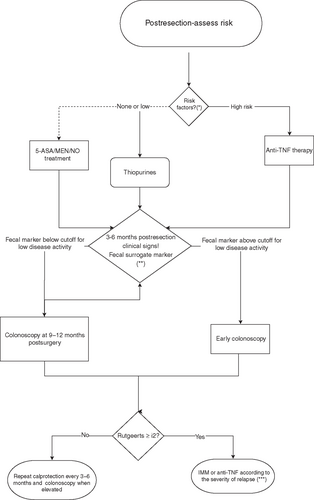

HOW TO CHOOSE THE TYPE OF POSTOPERATIVE MAINTENANCE MEDICATION

Selecting the most appropriate therapeutic intervention for prevention of postoperative recurrence of CD remains a challenging clinical problem, especially in children in whom there is a lack of Level 1 evidence. Although the majority of patients with CD will eventually require surgery, most of those who are left untreated postoperatively will develop disease recurrence within a few years and many will need reoperation within 10 years (37., 38., 195.). Given the fact that children who undergo resection have a lifelong risk for repeated resections and are at risk to develop short bowel syndrome, the issue of preventing recurrence is of the greatest importance. The suggested algorithm is presented in Figure 1.

Therapeutic algorithm for preventing postoperative recurrence in pediatric Crohn disease. (*) High-risk factors are growth failure, delayed puberty, short duration from diagnosis to surgery, extensive resection (>40 cm), penetrating behavior, active disease beyond resected site. (**) Fecal markers cutoff according to local reference value (see text, Section 10, practice point 4). (***) Decision of the given therapy according to the severity of relapse and disease history. IMM = immunomodulator; MEN = maintenance enteral nutrition.

Practice points:

- Low-risk patients may be given no prophylaxis medication after surgery or only 5-ASA if signs of colonic involvement. Maintenance enteral nutrition may also be considered (196,197).

- In high-risk patients (extensive disease, short disease duration from diagnosis to surgery, recurrent surgery, long resected segment, surgery for fistulizing disease, disease complications, perianal disease, smoking) anti-TNFα is the most effective therapy, even in patients who were treated before surgery.

- Ileocolonoscopy is recommended 6 to 9 months after surgery with treatment step-up if Rutgeerts score is ≥ i2)

- Fecal calprotectin may be evaluated at regular intervals, for example, every 3 to 6 months, with further endoscopy in case of significant increase. Most published studies suggest best cutoff level of fecal calprotectin as 100 μg/g for predicting endoscopic recurrence but lower values of 60 or 75 μg/g have also been suggested (198,199).

The role of endoscopy-guided treatment to modify clinical outcome has been evaluated in several adult retrospective studies with conflicting results (158., 200., 201.). A prospective study (174 patients enrolled) revealed that at 18 months after surgery recurrence occurred in 49% versus 67% (randomization 2:1 to either endoscopy tailored treatment at 6 months postoperatively or control group (P = 0.028); patients in both groups received prophylaxis starting immediately after surgery (153.). A small Japanese prospective study with a 5-year follow-up period has revealed comparable results (193.). Alike in adults, a constant rise in fecal calprotectin is suggestive of disease recurrence in children (161.).

PERIANAL DISEASE

Perianal CD is a complex condition that is frequently refractory to treatment and needs a combined medical and surgical approach. In adult CD, up to 54% of patients present with perianal complications, perianal fistulas develop in 20% and recurrence occurs in approximately 30% of patients (202., 203.). The majority of patients with perianal fistulas have colonic disease involving the rectum (204.). Perianal manifestations including fissures and skin tags are present in 13% to 62% of children with CD (205.). Perianal fistulas are present in 10% to 15% of the time at diagnosis (206.-208.).

Diagnostic Approach

Various fistula classifications have been proposed either relating fistulas to the ano-rectal ring (high or low) or more precisely as described by Parks, using the external sphincter as the reference point (29.). For clinical practice, classification into simple (superficial involvement of the external sphincter by single fistula tract without rectal inflammation or abscess) and complex (deep or extensive involvement of the sphincter musculature by fistula tract or associated rectal inflammation, abscess or stenosis) perianal fistula is more relevant (207., 210., 211.). For the management of perianal fistulizing CD it is essential locate the fistula origin, establish the anatomical course of the fistula tract and exclude or identify the presence of associated rectal inflammation or abscess (207., 211., 212.).

Statement 21. Pelvic MRI and evaluation under anesthesia by a surgeon with experience in pediatric anorectal disease should be among the initial procedures in evaluating a child with suspected complex perianal CD. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 22. Disease extension should be re-evaluated by ileocolonscopy in all patients with complex perinanal disease manifesting after primary diagnostic investigations of CD. Concomitant intestinal lesions (inflammation, stenosis) have both prognostic and therapeutic relevance. (Agreement 100%)

When the child has perianal pain an abscess is almost always present. In such situations prompt evaluation under anesthesia, including drainage, is the procedure of choice to minimize damage to the sphincter (212.-214.). Nevertheless, pelvic MRI has an accuracy of 76% to 100% for fistulae in studies performed in adults and it has become an essential tool as well for children providing important information for the surgeon about the tract of the fistula and identifying an abscess (203., 214.-219.). When pain is not present, most children will tolerate a gentle digital rectal examination to identify a stricture or fluctuance. The most common approach to evaluate perianal CD for children involves an external and rectal examination followed by MRI imaging and examination under anesthesia by an experienced surgeon (212.). Fistulography is rarely needed for evaluation of the fistula tract. Endoscopic ultrasound has also been used to diagnose and guide management of perianal disease with satisfactory result (220.). Disease extension should be re-evaluated by ileocolonoscopy in all patients with complex perianal disease that develops after primary diagnostic investigations of CD.

A less common condition described as severely destructive form, separate to the more commonly recognized perianal disease is reported rarely but is a real treatment challenge. Markowitz et al (221.) were the first to report in 1995 such a severe and mutilating form and named it highly destructive perianal disease (HDPD). They identified 67 of 230 patients (29%) (children and adolescents) with perianal disease of which only 6 (2.6% of total children) were described with HDPD. Since then there have been a few other case reports highlighting the severity of the condition and difficulty of treatment (222.-225.). It is characterized by visualization of deep perianal ulceration and tissue destruction associated with copious exudate with involvement of perineum and surrounding areas. Unfortunately, HDPD is not particularly responsive to medical therapies including hyperbaric oxygen even with the advent of biologics and often diverting the fecal stream via an ostomy to promote perianal healing is the only effective form of management. Successful skin grafting of the perianal ulceration following fecal stream diversion has been described (223., 225.).

Treatment of Perianal Fistulae

Statement 23. Treatment of perianal CD should be based on combination of surgery, antibiotics and biologics. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 24. Presence of perianal abscess should be ruled out early and when detected drainage should be discussed with the surgeon. (Agreement 100%)

Statement 25. Placement of noncutting seton should be considered in all complex fistula tracts, especially in those with recurrent abscesses. (Agreement 100%)

Practice points:

- In asymptomatic simple perianal fistulae no actions are needed but careful monitoring is recommended.

- Symptomatic simple fistulae should be treated either with placement of noncutting seton or in superficial cases with fistulotomy.

- Uncomplicated fissures may be treated with topical therapy.

- Anti-TNFα agents should be used as primary medical induction therapy for complex perianal CD in combination with appropriate surgical intervention after effective abscess drainage. After successful induction, anti-TNFα scheduled maintenance is mandatory. Antibiotics may be used as second line medical treatment until drainage from the abscess or fistula has stopped. The evidence for the use of AZA-6MP is weak.

- Antibiotics, metronidazole (20–30 mg · kg−1 · day−1) or ciprofloxacin (10–20 mg · kg−1 · day−1) are most widely used.

- The timing of removal of setons depends on subsequent therapy and treatment response.

- Anti-TNFα should be continued for at least 1 year following with abscess drainage.

- In case of failure of IFX, ADA is recommended. In case of failure to respond to available anti-TNFα agents and other biologics with proven efficacy in CD, AZA/6-MP, methotrexate, or tacrolimus with antibiotics may be used.

- The use of cutting setons may damage anal sphincter and induce incontinence.

- Fistulectomy and fistulotomy carry a risk of incontinence and therefore should only be performed by expert surgeons (13). Endorectal mucosal advanced flap is an option in the absence of rectal disease and in case of a single fistula source that it is easily identified.

- Proctectomy (and permanent diversion) may be considered when a patient has severe rectal and perianal disease.

When a simple perianal fistula is symptomatic there is consensus in adults to use antibiotics as the first therapeutic option, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (AZA/6-MP) as the second option and IFX as a third option. Combined medical and surgical approach is favored (212.).

There is lack of controlled evidence on the efficacy of antibiotics that are the first-line therapy especially in simple fistula in children and adults (209., 211., 212.). There are no controlled trials assessing the effect of AZA/6-MP on the closure of perianal fistulae as primary endpoint (204., 226., 227.). Small uncontrolled series on efficacy of intravenous cyclosporine A and oral tacrolimus have been reported (228., 229.).

In adults, IFX was the first agent shown to be effective in an RCT for inducing closure of perianal fistulae and maintaining response over 1 year (complete closure in 55% vs 13% in the placebo group) (230.). In another trial, randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of repeated infusions of infliximab in patients who improved after an initial infusion of infliximab (ACCENT) II, complete closure was seen in 36% at week 54. Comparable results with ADA (Crohn trial of the fully human antibody adalimumab for remission maintenance [CHARM]) have been observed in adults (231., 232.). Results on the use of ADA following IFX failure or intolerance are conflicting (233., 234.). In fistulizing disease, maintenance on IFX reduced hospitalization and surgery (235., 236.).

In pediatrics the post-hoc analysis of 22 patients with perianal CD of REACH study, response rates were 41% at week 2 and 72% at week 54 (237.). In another study, long-term clinical response to IFX was observed in 9 of 16 patients with refractory CD and draining fistulae (238.). Top down strategy compared with a step up approach in a small group of pediatric patients showed better results (3/6 in the step up group compared with 12/12 completely closed in the top down group) at 1 year (239.). As of yet there are no published studies on the use of ADA in this context.

The combination of IFX and surgery with seton placement gives better results, longer effect duration and lower rate of recurrence to either treatment alone most likely related to better drainage of the abscess and fistulae (240.-243.). One strategy is to place seton before the start of therapy with IFX. Loose noncutting setons are used because a cutting seton may cause damage to the anal sphincter resulting in incontinence (207.). In a recent retrospective study in 13 adolescent patients with complex perianal fistulae treated with seton placement and then IFX, >90% responded. Fistula response 8 weeks was complete in 77% and partial in 15%. Fistula recurred in 3/13 (23%) patients, 2 on biological therapy and 1 after discontinuation of treatment (244.). The loss of response to biological therapy was associated with detectable drug antibodies.

Anti-TNFα medication may be used as a first choice of treatment for complex perianal CD following radical surgery of “Cone-like” fistulectomy of each fistula tract with sparing of the sphincter (211.). In the recent ECCO/ESPGHAN pediatric guidelines for medical management of CD anti-TNFα therapy is recommended as primary induction and maintenance therapy for children with active perianal fistulizing disease in combination with appropriate surgical intervention (11.). The tract may persist as assessed by MRI and drainage usually recurs if treatment is stopped (212.). Surgical treatment always is considered indicated for complex perianal CD. A perianal abscess should always be drained.

There is uncontrolled evidence that local injection of IFX close to the fistula tract may be beneficial in patients not responding to or intolerant of intravenous IFX (11., 245.). Also, intralesional administration of mesenchymal stem cells has been reported as a promising treatment option in complex perianal fistula in adults (246.).

A diverting ostomy or proctectomy may be necessary for severe disease refractory to medical therapy. In such patients the risk of the ostomy becoming permanent is significant (207.). Rectal stenosis or strictures are relatively rare findings in children with CD and most commonly located at the dentate line. They may respond to repeated anal dilatation under anesthesia. A refractory short stricture may be amenable for stricturoplasty, whereas more extensive strictures may require fecal diversion with or without proctectomy.

Other Fistulizing Crohn Disease

The most common fistulae in CD are enteroenteric. Surgical management typically involves resection of the diseased segment of bowel and closure of the connection with uninvolved intestine. Similarly, enterovesical fistula are managed by resection of the diseased segment and primary closure of the bladder.

Enterocutaneous Fistulae

Management of enterocutanoeus fistulae reported in children with CD is a complex challenge (36.). IFX had modest effect on 25 patients out of 282 with rectovaginal fistulae (236.). Early re-operation to close a fistula tract is often associated with recurrence or further complications. Optimizing the nutritional status is of importance in such situations (212.).

Enterogynecalogical Fistulae

In low anal-introital asymptomatic fistula surgery may not be necessary. In patients with symptomatic fistula surgery may be necessary including diverting ostomy.

Rectovaginal fistulae have been rarely reported in children (221., 247.). Surgery for such a condition should be tailored individually. Resection of the diseased gut segment is usually necessary when small bowel or sigmoid-gynecological fistulae are present (212.). Rectovaginal fistulae not responding to conservative treatment should be treated surgically with an advancement flap and diverting-ostomy when necessary because of the presence of unacceptable symptoms (212., 248.-251.). In recurrent fistulizing disease gracilis muscle interposition has been successfully reported (252., 253.).