Clonal Hematopoiesis in Hospitalized Elderly Patients With COVID-19

SBo and SBa contributed equally to this study.

This work was financially supported by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG (Basel, Switzerland) as well as research grants by the Promedica Foundation Chur, and by the Swiss Cancer League (KFS-4885-08-2019) to Steffen Boettcher.

The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.hemaspherejournal.com).

Abstract

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) results from the acquisition of somatic mutations in oncogenic driver genes in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) leading to the expansion of blood cell clones in otherwise healthy individuals.1-3 CH is rarely found in younger individuals but its prevalence greatly and continuously increases beyond 60 years of age when it can be detected at frequencies of 10% to 20%.4, 5 Besides being a pre-malignant condition for myeloid neoplasms including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS),6, 7 CH is also a strong risk factor for thromboembolism8 and cardiovascular disease.9, 10 Mechanistically, it has been shown that loss-of-function mutations in the epigenetic modifiers DNMT3A and TET2 lead to de-repression of genes for inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).11, 12 Thus, monocytes and macrophages with mutations in DNMT3A and TET2 acquire a strong pro-inflammatory phenotype thereby driving development and rapid progression of atherosclerosis and overt cardiovascular disease.9, 10 A clear pathogenic contribution of CH to other inflammatory diseases has not yet been formally established but it is an active area of research.13-15

Infection with the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that is characterized by an interstitial pneumonia of highly variably clinical extent. While younger individuals that contract SARS-CoV-2 often remain completely asymptomatic, severe and fatal cases of COVID-19 are being observed with an increasing age reaching a fatality rate of up to 60% in patients 80 years and older.16 However, the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 has remained enigmatic.17 An excessive release of inflammatory cytokines (ie, cytokine storm) has been observed in severe COVID-19.18

The striking similarities between CH and severe COVID-19—both being associated with an advanced age and a pro-inflammatory state—led us to hypothesize that the presence of CH might act as a patient-intrinsic, disease-modifying factor for COVID-19 conferring a higher risk for the development of severe COVID-19.

We studied a cohort of n = 144 individuals ≥50 years with or without COVID-19 and hospitalized at 3 centers in Switzerland (University Hospital Zurich n = 94, Triemli City Hospital Zurich n = 14, and Cantonal Hospital Winterthur n = 36). The individuals were enrolled in this study after giving informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (KEK-ZH No. 2020–00892) in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. DNA was extracted from 0.3 ml whole peripheral blood using the Maxwell® CSC DNA Blood Kit (Promega, Madison, USA) and was sequenced using the FoundationOne® Heme assay (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, USA). NGS libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq™ 2500 system. NGS data were analyzed according to the standardized FoundationOne® Heme assay analysis pipeline. Only mutations with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 0.01 to 0.4 were reported if they affected genes recurrently mutated in CH and myeloid malignancies.1, 9 Non-parametric tests were used to calculate the significance of differences as indicated in the figure legend and was considered statistically significant if p values were <0.05. Statistical analysis was calculated using Prism software.

We enrolled n = 102 patients ≥50 years that required hospitalization for confirmed COVID-19, and in addition, n = 42 age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched control patients hospitalized without COVID-19 in three centers in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland, yielding a total cohort of n = 144 patients (Table 1). Patients with COVID-19 were stratified as having moderate vs severe COVID-19 based on the requirement for treatment on the intensive care unit (ICU). Furthermore, patients that died on the regular ward due to COVID-19 were also classified as having severe COVID-19. The most common reason for this latter clinical setting was the patient's wish not to receive intensive care. The median age of patients with moderate (n = 47) and severe (n = 55) COVID-19 was in both cohorts 67 years (Table 1). Altogether, our cohort was comparable to other COVID-19 cohorts reported so far.19

In order to determine the prevalence of CH in our cohort of elderly patients with COVID-19, DNA extracted from whole blood was subjected to targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) using the well-validated FoundationOne® Heme assay comprising a panel of 406 genes.20 In addition, we sequenced a well-matched cohort of control patients without COVID-19 to account for the high variability of CH prevalences reported in the literature (Table 1).

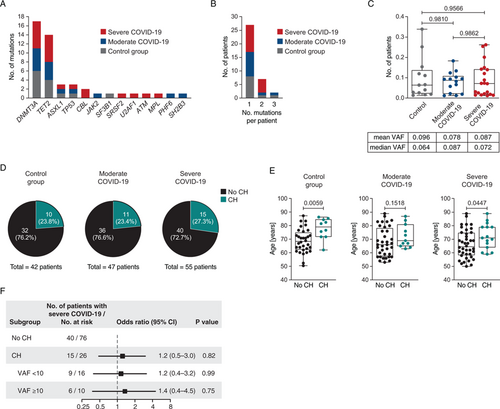

With a median coverage of 607, we detected 47 mutations affecting 13 genes in 36/144 (25%) of patients (Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HS/A90). The mutational landscape was comparable to previous studies on CH (Fig. 1A), and as expected, mutations in DNMT3A and TET2 were most frequently detected accounting for 66% of all mutations.21 There was no obvious enrichment of particular mutations in patients with either moderate or severe COVID-19, or in the control cohort. The remaining mutations affected genes commonly mutated in CH such as ASXL1, TP53, CBL, and genes for components of the spliceosome (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1) at, however, much lower frequencies.1, 3 More than one mutation (up to 3 mutations) per patient were detected in 9/36 (25%) patients with CH (Fig. 1B). The median VAF in the control group, and in patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 was 0.064, 0.087, and 0.072, respectively, which was not significantly different (Fig. 1C).

Altogether, at least one mutation was detectable in 11/47 (23.4%) of patients with moderate COVID-19, in 15/55 (27.3%) of patients with severe COVID-19, and in 10/42 (23.8%) of patients without COVID-19 (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the well-established age association of CH, patients with detectable mutations were older than patients without CH, and this was true for the control subgroup, and for patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 (Fig. 1E).

Clonal hematopoiesis in elderly patients with COVID-19. (A) Mutational landscape of somatic mutations detected in elderly patients with moderate or severe COVID-19, or in a matched control group of patients without COVID-19. (B) Number of patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 or control patients with ≥1 mutation. (C) Variant allele frequencies (VAFs) in the matched control group, and in patients with moderate or severe COVID-19, respectively. Statistical significance was calculated using the Mann-Whitney test. (D) Proportion of patients affected by CH in the control group, and in patients with moderate or severe COVID-19. (E) Age of patients affected by CH in the control group, and in patients with moderate or severe COVID-19. Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate statistical significance. (F) Odds ratios for the association between CH and the development of severe COVID-19 further stratified according to a variant allele frequencies (VAF) of <0.1 or ≥0.1 (statistical significance was calculated using Fisher exact test).

Importantly, the presence of CH was not associated with a higher likelihood of severe COVID-19 (odds ratio, 1.2; CI 95%, 0.5 to 3.0; p = 0.82) (Fig. 1F). Moreover, it has previously been shown that CH carriers with a VAF of ≥0.1 (corresponding to ≥20% of all blood cells harboring the mutation) had a greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease driven by inflammatory cytokines.9 However, clone size did not significantly affect the risk for severe COVID-19 in our cohort (Fig. 1F).

In summary, we observed a high prevalence of CH in hospitalized elderly patients with COVID-19. Importantly, however, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of CH, its mutational landscape, and clone size in our cohort of patients with moderate or severe COVID-19, and in a well-matched control group of patients without COVID-19. Future studies in larger COVID-19 patient cohorts might be required to unravel a disease-modifying impact on disease severity of a smaller yet potentially clinically relevant magnitude.