Making Sustainability Tangible: Land O'Lakes and the Dairy Supply Chain

We appreciate Rebecca Kenow, Director of Sustainability for Land O'Lakes, who read the manuscript for content applicable to Land O'Lakes. The usual disclaimer applies. Senior authorship is not defined. A copy of a teaching note can be obtained by contacting the first author.

© The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract

This case study examines the challenges of implementing a vaguely defined concept called sustainability in a large organization that also has a cooperative structure. Stakeholder theory is described and applied to a multinational dairy firm. The case firm, Land O'Lakes, must balance the needs of multiple constituencies: the general public, employees, cooperative members, external funding organizations, and the management team. One challenge is to define sustainability for the entire dairy industry. The case discusses the strategies used by firms in developing a sustainability response where the tradeoffs between different strategies are between credibility and autonomy and using an industry rather than a firm-level response.

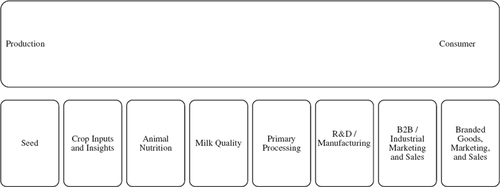

Land O'Lakes, Inc. is a U.S.-based agricultural cooperative organized into three main lines of business: Dairy Foods, Purina Animal Nutrition, and Winfield (crop inputs). Figure 1 shows the company's portfolio of businesses, which is unlike many of its competitors in that it supplies producers with seed, crop inputs, and services, as well as animal nutrition and services. Land O'Lakes then buys their fluid milk and creates various processed products from that milk.

Overview of Land O'Lakes Business Units in 2015

As a food company, Land O'Lakes faces issues related to sustainability from its stakeholders. Sustainability is a broad topic that applies to all firms in the dairy industry, but a unique problem for Land O'Lakes and other dairy cooperatives is that its ownership structure includes farmers, producers, and ranchers, as well as other cooperatives. Ross, Pandey, and Ross (2015) studied the corporate sustainability reports of 14 leading food economy firms between 2009 and 2011 and reported that most firms appear to be more intrinsically motivated than extrinsically motivated to pursue sustainability. Rangan, Chase, and Karim (2015) note that many corporate social responsibility programs are not necessarily designed for strategic reasons. However, neither study includes examples of closely-held firms or cooperatives, which are important organizational structures of the U.S. food economy as noted by Boland, Golden, and Tsoodle (2008). This research case study discusses the evolution of corporate sustainability concepts, describes different approaches that large organizations can take in pursuing sustainability initiatives, and looks at how Land O'Lakes has chosen to apply this concept within their Dairy Foods business unit.

Theoretical Foundations of Sustainability

The concept of sustainability has its roots in stakeholder theory. The Stanford Research Institute defined the concept of a stakeholder in 1963 as “those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist” (Freeman 1984). Stakeholder theory helps describe why sustainability efforts have become an important issue for firms as stakeholders are driving the firms to address the issue of sustainability. Donaldson and Preston (1985) notes that “Stakeholder theory is managerial in the broad sense of that term. It does not simply describe existing situations or predict cause-effect relationships; it also recommends attitudes, structures, and practices that, taken together, constitute stakeholder management.”

Stakeholder management requires simultaneous attention to the legitimate interests of all appropriate stakeholders, both in the establishment of organizational structures and general policies and in case-by-case decision-making. Stakeholder theory does not presume that managers are the only rightful locus of corporate control and governance. In other words, the main points behind stakeholder theory are to actively include the input and opinions of everyone who has a stake in the outcomes of the organization, and to ensure that as many stakeholders as possible support the decisions of management.

The second source of theory behind sustainability efforts is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), an attempt to standardize and publicize corporate sustainability activities by publishing guidelines against which corporations are invited to report their activities and progress. According to GRI, over 5,000 corporations apply these guidelines in more than 90 countries (Global Reporting Initiative 2015). The three industry sectors that most commonly pursue sustainability efforts are financial services, energy, and food and beverage products. As the generally accepted standard for sustainability reporting across industries, including the food economy, the GRI also publishes industry supplements where it summarizes and recommends specific areas on which organizations in the industry should both act and report.

Sustainability within the Food Processing Sector

Sourcing and supply chain issues are the most active sustainability theme in the food processing sector. This is reflected in GRI (2011), which states “sourcing has been identified by the Working Group for this Supplement and other contributors as a new issue of critical importance to the sustainability of the food processing sector.” These activities are similar to information asymmetries as noted by Hennessy (1996).

Broadly speaking, supply chain sustainability considerations may include topics such as transportation, food safety, and packaging. In this context, however, supply chain sustainability means monitoring and directing the sourcing of inputs and managing supplier relationships. The GRI suggests that any organization seeking to implement sustainable practices address the following topic areas in relation to their sourcing and supplier relationships: economic; environment; labor; human rights; society; and product responsibility.

Examples of these topics in the food processing sector are: percentage of purchased volume from suppliers compliant with a company's sourcing policy (economic); percentage of wild caught and farmed seafood (environment); nature and scope of any programs and practices such as in-kind contributions, volunteer initiatives, knowledge transfer, and partnerships and product development that promote access to healthy lifestyles, prevention of chronic disease, access to healthy, nutritious, and affordable foods, and improved communities in need (society). Finally, in determining the riskiness of a given sustainability effort, the GRI supplement further considers whether raw materials are produced or sourced in an area of resource constraint, high conservation value, or social, political, or economic vulnerability.

Organizations may use tools such as supplier surveys, codes of conduct, or supplier audits to ensure their suppliers' sustainability performance. In effect, unless the organization has fully vertically integrated the sourcing of raw materials, sourcing and supply chain sustainability activities are passed backwards to suppliers and are not necessarily engaged in by the organization itself. A number of articles written by agricultural economists such as Kinsey (2001) and Sexton (2013) have noted the changing industrial organization of the food economy and how retailers and other buyers are increasingly differentiating products.

Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon (2005) place sustainability efforts into four distinct categories: initiatives pursued; certification schemes; audits; and codes of conduct or other tangible and intangible actions. At a high level, these efforts differ on the amount of autonomy the corporation retains and the amount of credibility that the strategy supplies. Taken together, these efforts represent an organization's sustainability strategy.

First-party Strategies: Initiatives Pursued

In a first-party strategy, the company goes it alone or works with one outside stakeholder partner. The methods by which a company pursues sustainability include guidelines, internal audits, self-reporting, or other company-specific measures. While this strategy may engage stakeholders for input on various initiatives, ultimate accountability and regulation takes place with the company itself. There are no external mechanisms for compliance, except whistleblowing from outside stakeholders if the company's efforts are found to lack transparency, accountability, or efficacy in relation to its objectives or external standards.

Because they are motivated by the organization itself, first-party programs can be high risk and high reward. When firms market their pursuit of sustainability above and beyond their demonstrable actions, they may be accused of “greenwashing,” a term used by field biologist Jay Westervelt regarding the hospitality industry's practice of placing signs in hotel rooms promoting the reuse of towels to “save the environment.” Westervelt noted that, in most cases, little or no effort toward reducing energy waste was evident due to the lack of cost reduction from this practice. Parguel, Benoit, and Larceneux (2009) suggest that poor sustainability ratings combined with high levels of marketing about its sustainability efforts contribute to the perception that a company is greenwashing. However, the ability to mislead stakeholders through greenwashing is becoming more difficult. Various sustainability rating agencies and the GRI can independently verify the effectiveness of a company's sustainability efforts.

One first-party method is to establish supplier codes of conduct, which can govern either specific supplier choice decisions or more general company decisions. Besides the time and effort dedicated to idea generation, codes of conduct take few resources to implement and are the most visible element in a corporation's sustainability approach. Codes of conduct were widely implemented in the 1990s, and they state the standards that suppliers are expected to meet (Andersen and Skjoett-Larsen 2009). It can be argued that they only act as public relations mechanisms at best and do not lead to accountability on the part of the company, but some authors contend they are as legitimate as laws, only without a government enforcement mechanism (Sethi 2002; Sobczak 2006). All in all, codes of conduct do not go much beyond mandating that suppliers must be legally compliant wherever they operate.

Another novel first-party approach that goes beyond supplier codes of conduct is the “supplier scorecard,” as most prominently implemented by Walmart in 2006. Supplier scorecards were first used with regard to packaging and later expanded to other elements of supplier sustainability. As part of supply chain management efforts, sourcing companies previously used scorecards to monitor suppliers' performance in the areas of risk, on-time delivery, price, and inventory. In a sustainability context, this internal control mechanism is turned outward and pushed onto suppliers. As part of the Walmart Sustainability Supplier Assessment developed in 2008, the company asks suppliers to respond to 15 questions, shown in table 1. The answers are evaluated to identify the supplier as “Below Target,” “On Target,” or “Above Target” in sustainability (Walmart 2012).

| Energy & Climate | 1. Have you measured your corporate greenhouse gas emissions? |

| 2. Have you opted to report your greenhouse gas emissions to the Carbon Disclosure Product (CDP)? | |

| 3. What is your total annual greenhouse gas emissions reported in the most recent year measured? | |

| 4. Have you set publicly available greenhouse gas reduction targets? If yes, what are those targets? | |

| Material Efficiency | 1. If measured, please report the total amount of solid waste generated from the facilities that produce your product(s) for Walmart for the most recent year measured? |

| 2. Have you set publicly available solid waste reduction targets? If yes, what are those targets? | |

| 3. If measured, please report total water use from facilities that produce your product(s) for Walmart for the most recent year measured? | |

| 4. Have you set publicly available water use reduction targets? If yes, what are those targets? | |

| Natural Resources | 1. Have you established publicly available sustainability purchasing guidelines for your direct suppliers that address issues such as environmental compliance, employment practices, and product/ingredient safety? |

| 2. Have you obtained 3rd party certifications for any of the products that you sell to Walmart? | |

| People and Community | 1. Do you know the location of 100 percent of the facilities that produce your product(s)? |

| 2. Before beginning a business relationship with a manufacturing facility, do you evaluate the quality of, and capacity for, production? | |

| 3. Do you have a process for managing social compliance at the manufacturing level? | |

| 4. Do you work with your supply base to resolve issues found during social compliance evaluations and also document specific corrections and improvements? |

Walmart further extended this program to a worldwide Sustainability Index, which transparently rates over 60,000 suppliers against one another. While Walmart's initiative was the most ambitious, arguably because they had enough buying power to compel supplier participation, some food corporations have adopted the scorecard approach. Notably, Procter & Gamble deployed a scorecard to an initial group of 400 suppliers in 2010. The company listed three goals: (1) enhancing supply chain collaboration; (2) improving key environmental indicators; and (3) encouraging the sharing of ideas and capabilities to deliver more sustainable products and services to consumers. The challenge, as with many sustainability reporting initiatives, is standardization to decrease the reporting burden on suppliers.

Other first-party approaches include proactively communicating with individual suppliers or farmers in the company's supply chain to assist in their sustainability efforts, or to improve their financial well-being. Feder, Murgai, and Quizon (2004) note that one popular initiative is investing in “farmer field schools.” These programs can supplement sustainable product certification processes while also reducing the burden on suppliers in meeting certification standards. Ironically, providing more training for suppliers of certified products increases the availability and supply of these products, consequently lowering their prices and making certification a somewhat useless tool, at least from the grower's economic perspective.

Second-party Strategies: Certification Schemes

In second-party strategies, an industry association or corporate partnership implements initiatives, sets guidelines, or provides certification schemes. The participating companies may “outsource” sustainability to the association, although they will more likely retain control of operations themselves with the promise of complying. Again, the association may receive input from multi-stakeholder groups, but its members are industry participants. The enforcement mechanisms are often unknown or unclear as the associations emphasize collaboration rather than compliance.

Moving from first-party to second-party strategies, the primary exchange is autonomy for credibility. Because multiple corporations are involved, a company is less likely to “cheat” on marketing sustainability successes. This strategy also implies that if greenwashing or unsustainable practices are found, the negative consequences will be felt industry-wide, thus lessening the damage experienced by the firm in relation to its competition. As with many first-party strategies, a large part of establishing credibility is communication and achieving stakeholder support without the participation of governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

One weakness of second-party strategies is that they may have to incorporate other external stakeholders to gain credibility. For example, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) was originally developed by the industry members of the American Forest and Paper Association. The SFI certified forest management groups as logging sustainably, yet the audits could be made by any one of a number of groups (first-party, second-party, or third-party), and a tremendous amount of flexibility as to which standards and indicators were used. This led to certification being primarily process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. In other words, companies could become certified as SFI sustainable if they merely stated some form of responsible forest management policy. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a multi-stakeholder (fourth-party) entity that applied more stringent certification standards, upstaged the SFI, which was so heavily criticized for its soft standards that it ultimately incorporated third-party entities into its organization in 2007.

Third-party Strategies: Audits

Third-party strategies involve an independent, outside entity certifying that the company is sustainable, despite how the outside entity defines sustainability. While firms may provide input into the creation of guidelines or certification procedures, the evaluation and compliance mechanism is independent. Third-party strategies may be forced upon companies when governments impose regulations. If this is not the case, companies generally have to be proactive in pursuing the certification or complying with the entity's guidelines. While adhering to outside standards signifies a complete loss of autonomy with potentially high levels of credibility, companies may be able to choose from multiple certification schemes in some industries such as coffee, forestry, and seafood.

This approach has the dual benefit of signaling sustainability to stakeholders while serving as a marketing tool to consumers that factor sustainability into purchasing decisions. The certifications can be issue- or product-based. The Fair Trade Alliance and Rainforest Alliance are two examples of organizations that certify based on certain economic or environmental sustainability issues of production across many products such as “fair” prices. The Roundtable on Sustainable Soy, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, and Marine Stewardship Council offer certifications for soy, palm oil, and seafood sourcing, respectively, which mostly reflect methods of production such as not clearing rainforests for new palm oil production.

The GRI can be considered a third-party entity that certifies a company is adequately reporting its sustainability efforts in relation to the guidelines it establishes. Product seals, gained by third-party certification, may command a price premium as well. They may also induce the highest level of competitive behavior. Furthermore, the published percentage of sourced products that are certified sustainable is powerful, purely because it is a straightforward, comparable, numerical measure in a field plagued with few such metrics. Without explaining the intricacies of company-specific sustainability policies, stakeholders can point to the current or goal-oriented percentage to evaluate competitive sustainability outcomes.

Fourth-party Strategies: Codes of Conduct

In a fourth-party strategy, a multi-stakeholder sustainability alliance (MSSA) implements initiatives or sets guidelines similar to second-party strategies. The primary difference between fourth- and second-party strategies is the composition of the alliance; specifically, fourth-party strategies must encompass multiple stakeholder types. Depending on the alliance, the types may be trade associations, consumer interest groups, NGOs, supply chain partners, or governments. The alliance must contain non-industry entities. Similar to second-party strategies, the alliance may solicit input from all groups, and it emphasizes collaboration over compliance. Different groups of non-industry stakeholders presumably lend more credibility to results and established principles or codes. Moreover, credibility falls somewhere between second- and third-party approaches, as does autonomy level.

According to Dentoni and Peterson (2011), 22 out of the world's 50 largest multinational corporations (MNCs) in the food and beverage industry were members or founders of MSSAs. These authors suggest four propositions about MSSAs and their impact on participating corporations' credibility and strategy formation.

First, the authors note, “If it develops weak ties (or ‘bridges’) with multiple stakeholders through sustainability alliances, the MNC increases its partners' beliefs that the MNC has an effective sustainability strategy and the alliance partners will ultimately act favorably toward this strategy.” This proposition indicates that fourth-party strategies are generally effective in communicating sustainability by partnering, even if the ties are weak. These ties also persist outside the issue of sustainability. If an NGO and a corporation are aligned on one issue, it implies acceptance on other issues or at the very least makes it more difficult for NGOs to distance themselves and apply outside pressure to the firm.

Second, according to Dentoni and Peterson (2011), “The higher the status of the alliance partners, the stronger is the impact of the multi-stakeholder alliance on other alliance partners' subjective norms for acting favorably to the MNC's sustainability strategy.” The concept of “status” substitutes for credibility. Returning to the example of forestry, Greenpeace, which in this context was seen as the higher status organization because it had higher standards, did not endorse SFI certification even when the organization integrated with external entities. Because the FSC was supported by “higher status” partners like Greenpeace, companies that pursue FSC certification are generally viewed as more credibly sustainable (Christmann and Taylor 2002).

Dentoni and Peterson's (2011) third proposition is that “The interaction between sustainability alliance high-status partners' attitudes and subjective norms is positively associated with their behavior of acting favorably to the MNC's strategies.” In other words, if one credible (high-status) NGO joins another credible NGO in aligning with a corporation, they reinforce each other's implicit beliefs that the corporation is acting sustainably.

Finally, the authors note, “Sustainability alliance partners' behavior of acting favorably to a MNC's sustainability strategy is positively associated with other external stakeholders' (1) beliefs that the MNC has sustainability focus, (2) their attitudes towards acting favorably to the MNC and (3) their actual behavior of acting favorably to the MNC's sustainability strategy.” This proposition indicates that fourth-party strategies are generally effective in signaling sustainability to outside stakeholders, which takes proposition (1) a step further. The status of partners, as in propositions (2) and (3), plays a large role in the degree of effectiveness.

Background on Land O'Lakes

Land O'Lakes has been widely studied by agribusiness economists (Rodriguez-Alcala and Cook 2001; Boland and Katz 2003; Boland, Amanor-Boadu, and Barton 2004; Boland and Bosse 2010). Three company histories have been written, two by Ruble (1947, 1973) and one by El-Hai (1996). The company is a cooperative with a large number of links to land grant universities with endowments for graduate education, scholarships, named endowed chairs at several universities, including two in food economy-related topics, and it has supported other endowments in departments of agricultural and applied economics.

Between 2010 and 2014, Land O'Lakes (2015) had record years with regard to sales, sales volumes, net earnings, and cash patronage returned to members. This is also reflected in their return on invested capital and return on equity, which had an upward trend during this time period. Its crop inputs segment, Winfield Solutions LLC, had the greatest volume of sales revenue and income during this time. Winfield supplies member cooperatives and producers with crop protection products such as adjuvants, fungicides, herbicides, and pesticides, as well as alfalfa, corn, and soybean seed marketed through its Croplan trademarked brand. Purina Animal Nutrition LLC is its feed segment, which develops proprietary products and markets and distributes animal feed and services in lifestyle and livestock markets. Dairy Foods, which includes the Land O'Lakes branded products, procures about 13 billion pounds of milk annually from its members and manufactures and markets premium butter, cheese, refrigerated desserts including the Kozy Shack brand, as well as spreads and other dairy products. Land O'Lakes spends about $200 million annually on advertising and promotion and research and development. It is gradually exiting the layer hen and egg business.

The company's 2014 annual report indicated that Land O'Lakes, as a cooperative, is owned by 2,333 dairy producers, 1,241 agricultural producers, and 823 co-op members. Its ownership structure is similar to other dairy firms organized as cooperatives, although Land O'Lakes is much larger than most of these other firms. It is governed by a 24-member board of directors. The board determines policies and business objectives, controls financial policy, and hires the CEO. The dairy members nominate 12 directors from among themselves, and the agriculture members nominate 12 directors from among themselves. The nomination of directors is conducted within each group by region. The number of directors nominated from each region is based on the total amount of business conducted with the cooperative by that region's members.

Directors are elected to four-year terms at the company's annual meeting by voting members in a manner similar to a typical corporation. The board governs the company's affairs in the same manner as the boards of typical corporations that are not organized as cooperatives.

Land O'Lakes's dairy foods competitors are (1) other domestic and global dairy processors such as Dairy Farmers of America in products such as butter, cheese, and other dairy ingredients; and (2) multi-national firms with dairy portfolios such as General Mills. Land O'Lake's animal nutrition competitors are as follows: Cargill, a multi-national firm with an animal nutrition unit in its portfolio; independent retailers who have their own feed mills; and vertically integrated livestock and poultry producers. The company's crop input competitors include crop nutrient and chemical firms such as Agrium and Helena, and seed firms such as Monsanto, Pioneer, and Syngenta.

King (2012) summarized the science of design and sustainability programs are an example. In designing a sustainability program, Land O'Lakes has to account for its portfolio of enterprises. It must also take into account its ownership structure. Finally, it must consider its supply chain. The four categories of sustainability strategies cannot be applied uniformly across its businesses because some are food products and some are inputs into crops or livestock that make up a processed food product or beverage. For example, the retail focus of Dairy Foods imposes different requirements and standards on Land O'Lakes than the business-to-business markets of Winfield. Within its Dairy Foods unit, the company processes fluid milk from its members into manufactured dairy products. Because of its retail focus, and the large presence Land O'Lakes has in this industry, this business unit was the focus of efforts to develop a sustainability program.

Sustainability issues affect every firm in the dairy industry, although each firm may choose to embrace sustainability at differing levels of commitment. Specifically, any sustainability strategy developed by Land O'Lakes must take into account the producers who own Land O'Lakes. The same issues impact other firms. This has led to the formation of a broad dairy industry initiative.

Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy's Sustainability Council

The dairy industry has a long history of working together collaboratively in many activities through USDairy.com, which was developed to be a leading source of sustainability for the dairy industry. The website's focus is on dairy health and wellness, sustainability, trends and initiatives, and science and research. The objective of the Sustainability Council is to develop tools to measure, improve, and communicate sustainability performance. This effort began in 2007 and, in the following year, a Sustainability Summit was held to develop a vision, goals, and projects to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG). The dairy industry participants committed to a voluntary program to reduce GHG emissions from fluid milk production by 25% by 2020, increase business value across the value chain, and begin work on the innovation projects. In 2010, the first national GHG life cycle assessment of fluid milk established, in conjunction with additional secondary research, that the U.S. dairy industry contributes approximately 2% of total U.S. GHG emissions.

In 2011, projects included (1) efforts to measure, improve, and communicate dairy sustainability with the launch of the SaveEnergy, Dairy Plant SmartTM, and Dairy Fleet SmartTM tools; (2) the U.S. Dairy Sustainability Awards; and (3) the start of the Stewardship and Sustainability Guide for U.S. Dairy, a framework to measure dairy sustainability. The following year, the Farm SmartTM tool was piloted on farms accounting for a total of 60,000 acres with 60,000 cows producing the equivalent of 150 million gallons of milk. The Stewardship and Sustainability Guide is used by stakeholders to complete industry and stakeholder reviews and was piloted by dozens of farms, processors, and retailers.

By 2015, more than 800 firms were involved in this sustainability effort, including all the main participants in the dairy industry. Partners included individual dairy producers, cooperatives such as Land O'Lakes, firms involved in crop production (e.g., BASF, Syngenta, etc.), dairy manufacturing suppliers (e.g., DeLaval, Elanco), dairy processors (e.g., Chobani, General Mills), retailers (e.g., Kroger, Safeway), trade associations (e.g., Global Dairy Platform, EPA), and organizations (e.g., American Farmland Trust, Environmental Defense Fund).

The Center for U.S. Dairy participated in initiatives focused on sustainable agriculture and dairy production through the following organizations: Field to Market; the Keystone Alliance for Sustainable Agriculture; Global Reporting InitiativeTM Organizational Stakeholder Program; International Dairy Federation; National Initiative for Sustainable Agriculture; Sustainable Agriculture Initiative; Sustainable Food Lab; and The Sustainability Consortium. All of these organizations help establish codes of conduct, a key part of the fourth sustainability strategy described by Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon (2005).

Land O'Lakes Corporate Sustainability Report

The starting point for Land O'Lakes' sustainability strategy was the GRI guidelines for supply chain management within the food processing industry. Land O'Lakes chose to report in six different areas: resource management, animal care, sustainability, product quality and safety, supply chain integrity, and workplace environment. In each of these six areas, Land O'Lakes had different partners, and it used all four categories of sustainability strategies across these areas. The fourth-party strategy involving multiple stakeholders was the most common strategy used by Land O'Lakes.

Sixty of Land O'Lakes' members partnered with the Sustainability Council to pilot the Farm SmartTM tool for measuring GHG and a farm-level environmental footprint. These producers also tracked integrated pest management programs, soil quality, irrigation practices, and use of renewable energy technologies. All of this data was compared to regional and national averages. It also partnered with Field to Market: The Alliance for Sustainable Agriculture to help define and measure continuous improvement across its agricultural supply chains. Winfield invested in crop protection innovation to minimize driftable spray volume from crop chemicals, and it has used Answer Plot programs to provide information to farmers on tailoring agronomic practices to optimize yields and reduce environmental impacts.

Land O'Lakes also utilized the National Milk Producers Federation's FARM (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) program. Over 99% of its members' milk supply came from FARM-verified producers. All members of Land O'Lakes were required to participate in the FARM program. This is an example of a third-party strategy as a third party certified each farm.

Land O'Lakes looked inward, like many firms, to obtain efficiencies in manufacturing, logistics, and manufacturing. Software used by United Parcel Service was used to develop better time windows to pick up and deliver milk, as well as to establish routes that require its truck fleet to use only right hand turns, and the software uses a number of measurements collected in its trucks to monitor miles traveled, fuel usage, and other variables. Land O'Lakes participated in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Smartway program to reduce GHG, improve air quality, and enhance fuel efficiency. Dairy Foods had embarked on efforts to reduce energy usage and hoped to have a 25% reduction in energy intensity by 2018. A number of efforts have been used to recover waste heat and reduce natural gas and electricity use. Land O'Lakes has also been working to reduce water usage by 25% from its 2008 baseline assessment. Finally, Land O'Lakes has decreased the material used in its packaging by 10% since 2008.

Conclusion

Stakeholder theory provides a foundational link for understanding sustainability insofar as the perspectives of non-management groups, who have a stake in the company, need to be included in management decisions. Land O'Lakes worked with many different stakeholder groups in communicating its efforts about sustainability. These multiple stakeholders were an integral part of its programs. Supplier codes of conduct were an important strategy for Land O'Lakes, integrating both first- and fourth-party strategies. The company's sustainability program includes activities looking outward in its supply chain, and activities looking inward to become more efficient in its manufacturing, logistics, and distribution activities.

Discussion Questions

-

Why does Land O'Lakes need to develop a sustainability program? Why can it not ignore the advocacy groups pushing for a sustainability program?

-

How are sustainability efforts particularly conducive to a stakeholder theory approach? Do you think the dairy industry is more conducive or less conducive to organized sustainability efforts? Why?

-

What are the respective positions of each stakeholder group within Land O'Lakes? To what extent are they compatible with each other? To what extent are they not compatible? Which stakeholder groups hold more power in the context of implementing a sustainability program? Who can compel the organization to act in a certain way?

-

Do you agree with Land O'Lakes' fourth-party strategy approach? Why or why not?

-

What principles of sustainability are consistent with Land O'Lakes organizational goals? How does its membership structure as a cooperative influence its sustainability program?

-

How can Land O'Lakes measure their progress against the objectives they set for a sustainability program? Who will determine whether Land O'Lakes has actually implemented their sustainability program effectively?

-

What skills and competencies would be necessary to successfully implement a sustainability initiative?