Comparison of 3 mm versus 4 mm rigid endoscope in diagnostic nasal endoscopy

Abstract

Objective

Compare nasal endoscopy with 3 mm versus conventional 4 mm rigid 30° endoscopes for visualization, patient comfort, and examiner ease.

Methods

Ten adults with no previous sinus surgery underwent bilateral nasal endoscopy with both 4 mm and 3 mm endoscopes (resulting in 20 paired nasal endoscopies). Visualization, patient discomfort and examiner's difficulty were assessed with every endoscopy. Sino-nasal structures were checked on a list if visualized satisfactorily. Patients rated discomfort on a standardized numerical pain scale (0–10). Examiners rated difficulty of examination on a scale of 1–5 (1 = easiest).

Results

Visualization with 3 mm endoscope was superior for the sphenoid ostium (P = 0.002), superior turbinate (P = 0.007), spheno-ethmoid recess (P = 0.006), uncinate process (P = 0.002), cribriform area (P = 0.007), and Valve of Hasner (P = 0.002). Patient discomfort was not significantly different for 3 mm vs. 4 mm endoscopes but correlated with the examiners' assessment of difficulty (r = 0.73). The examiner rated endoscopy with 4 mm endoscopes more difficult (P = 0.027).

Conclusions

The 3 mm endoscope was superior in visualizing the sphenoid ostium, superior turbinate, spheno-ethmoid recess, uncinate process, cribriform plate, and valve of Hasner. It therefore may be useful in assessment of spheno-ethmoid recess, nasolacrimal duct, and cribriform area pathologies. Overall, patients tolerated nasal endoscopy well. Though patient discomfort was not significantly different between the endoscopes, most discomfort with 3 mm endoscopes was noted while examining structures difficult to visualize with the 4 mm endoscope. Patients' discomfort correlated with the examiner's assessment of difficulty.

Introduction

Hirschman employed a modified cystoscope to perform the first nasal endoscopy in 1902.1 Nasal endoscopy has now become an essential tool in management of sinonasal disease.2 Both flexible and rigid nasal endoscopes are employed for diagnostic nasal endoscopy in the office. The rigid nasal endoscope has the advantage of also being utilized in office based procedures such as endoscopic directed cultures, biopsies and debridements as opposed to the flexible nasal endoscope that requires both hands to be used for the examination. Although rigid endoscopes are available in various angles (0, 30, 45, 70), the most common endoscopes employed for office endoscopy are 0 or 30°. The 30° endoscope has the advantage of a larger panoramic view as compared to the 0°.

The 4 mm (mm) and 2.7 mm rigid endoscope have been widely for adult and pediatric use respectively. One concern expressed when comparing the thinner endoscopes versus 4 mm endoscopes is their durability and quality of image and illumination. Durability is a significant issue in purchasing decisions, as is their higher cost. Recently, newer endoscopes with diameters of 2.9 mm and 3 mm have been introduced to address these issues. Compared to the conventionally used 4 mm rigid endoscope, the smaller diameter endoscopes are intuitively presumed to offer improved visualization and patient comfort. As the utilization of nasal endoscopy has been used to improve diagnostic accuracy,3, 4 the narrower endoscopes are presumed to improve diagnostic capability.

The 3 mm 30° rigid endoscope is most commonly employed by the last author for office nasal endoscopy. 3 mm 30° rigid nasal endoscopes were purchased based on assumptions of improved visualization and patient comfort. We did not find any data in the literature that supported that assumption. We therefore conducted this study comparing 4 mm rigid endoscopes with 3 mm rigid endoscopes in three aspects: visualization, patient comfort and examiner's ease in performing the endoscopy.

Materials and methods

Ten adult individuals with history of no previous sinus surgery were enrolled in the study. There were 5 males and 5 female subjects. Verbal consent was obtained from all. Per our protocol, each participant was informed that they could choose to have endoscopy terminated at any time due to inability to tolerate the associated discomfort.

All endoscopies were performed by the last author to maintain consistency across examinations. Topical decongestant and local anesthetic sprays (1% phenylephrine and 4% lidocaine spray) were used in a standard fashion (2 sprays in each nostril). Each patient underwent bilateral nasal endoscopy with both 4 mm and 3 mm 30° rigid nasal endoscopes. See Table 1 for specifications of endoscopes used. Alternate patients were first scoped with the 4mm endoscope, so as to minimize any bias from uniform use of one particular-sized endoscope first. Endoscopic exam on each side with each endoscope was noted separately, resulting in a total of 40 nasal endoscopies (20 paired nasal endoscopies).

| Diameter | Angle of vision | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 4 mm | 30° | 18 cm |

| 3 mm | 30° | 14 cm |

Visualization of sino-nasal structures and pathology were noted first. A printed form with a list of anatomic structures was used to document visualization with each endoscopy. The list of structures included the uncinate process, ethmoid bulla, hiatus semilunar, maxillary ostium, accessory maxillary ostia, superior turbinate, spheno-ethmoid recess, sphenoid ostium, cribriform plate, nasopharyngeal structures and the valve of Hasner. See Table 2 for the complete list of structures. At the end of each endoscopy, structures were checked “yes” when visualized satisfactorily per previously determined criteria. Data was recorded for endoscopy on each side with both the 4 mm and 3 mm endoscope. The presence, site and severity of any septal deviation were also recorded for each side. Note was also made of the presence of any pus, polyps or masses. Provision was also made for recording any complication such as mucosal trauma, epistaxis or vaso-vagal attack.

| Target | Right 3 mm | Right 4 mm | Left 3 mm | Left 4 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle turbinate (anterior end) | ||||

| Choana (entire) | ||||

| Nasal floor | ||||

| Eustachian tubes | ||||

| Nasopharynx vault | ||||

| Fossa of Rosenmueller | ||||

| Superior turbinate | ||||

| Spheno-ethmoid recess | ||||

| Sphenoid ostium | ||||

| Ethmoid bulla | ||||

| Uncinate vertical part | ||||

| Uncinate horizontal part | ||||

| Hiatus semilunar | ||||

| Maxillary ostium | ||||

| Accessory maxillary os | ||||

| Retrobullar recess | ||||

| Suprabullar recess | ||||

| Frontal recess area | ||||

| Cribriform plate | ||||

| Polyp/mass/pus | ||||

| Valve of Hasner |

Patient discomfort level and the examiner's ease or difficulty was assessed with every endoscopy (Table 3). Patients were asked to rate discomfort on a standardized numerical pain scale (0–10) for each endoscopy on each side, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst possible pain they had experienced. They were also asked to rate their overall score of discomfort based on the experience of the entire endoscopic examination. The examiner rated difficulty of examination for each endoscopy on a hardship scale of 1–5 (1 being very easy and 5 being most difficult). The examiner then also scored an assessment of the overall difficulty.

| Patient pain score | Examiner difficulty score | Trauma to nasal mucosa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right 3 mm | |||

| Right 4 mm | |||

| Left 3 mm | |||

| Left 4 mm | |||

| Overall | |||

| Overall 3 mm | Not asked | Not applicable | |

| Overall 4 mm | Not asked | Not applicable |

Statistical analysis was made by using Microsoft Excel Software. Paired one tailed t test, chi test and correlation (r value) were used to study data.

Results

No subjective difference in image quality or illumination was noted between the 3 mm and 4 mm endoscopes. Endoscopy with the 3 mm endoscope was superior for visualizing the sphenoid ostium (P = 0.002), superior turbinate (P = 0.007), spheno-ethmoid recess (P = 0.006), vertical part of the uncinate process (P = 0.002), the cribriform area (P = 0.007), and the valve of Hasner (P = 0.002). No statistically significant difference was noted in visualizing any other structures (Table 4). We were unable to visualize the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus in any of the patients. Accessory posterior fontanelle ostium was noted in one patient on endoscopy with both the 3 mm and the 4 mm endoscope. The bulla was visualized on 11 endoscopies, but without significant difference between the endoscopes. We were not able to visualize the frontal recess, suprabullar recess or retrobullar recess on any endoscopic exam. Some degree of deviation of the nasal septum was noted in 8 of 10 patients.

| Structure | 3 mm | 4 mm | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle turbinate (Anterior) | 19 | 16 | 0.093 |

| Choana (Entire) | 18 | 17 | 0.53 |

| Nasal floor | 18 | 18 | 1 |

| Eustachian tube | 18 | 17 | 0.53 |

| Nasopharynx vault | 18 | 17 | 0.53 |

| Fossa of Rosenmueller | 18 | 16 | 0.263 |

| Superior Turbinate | 17 | 11 | 0.007 |

| Spheno-ethmoid recess | 18 | 12 | 0.006 |

| Sphenoid ostium | 11 | 5 | 0.002 |

| Bulla | 7 | 4 | 0.093 |

| Uncinate vertical part | 18 | 11 | 0.002 |

| Uncinate horizontal part | 13 | 9 | 0.072 |

| Hiatus semilunaris | 4 | 2 | 0.136 |

| Maxillary ostium | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Accessory max ostium | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Retrobullar recess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Suprabullar recess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Frontal recess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cribriform | 15 | 9 | 0.007 |

| Pus/polyp/mass | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hasner's valve | 4 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Trauma | 2 | 1 | 0.3 |

Patient's discomfort scores were not found to be significantly different for endoscopy with the 3 mm versus the 4 mm endoscopes (P = 0.18). The average score of the overall discomfort associated with the entire endoscopic experience was low at 2.65 (on the scale of 1–10). No significant difference in average pain score was noted between male and female subjects. One endoscopy with the 4 mm endoscope had to be terminated due to patient discomfort. In another instance, endoscopy with a 4 mm endoscope could not be made on one side due to a severely deviated nasal septum. Minor mucosal trauma was noted on 3 endoscopies, one with the 4 mm endoscope and in two endoscopies with the 3 mm endoscope. Both instances in which mucosal trauma was caused by the 3 mm endoscope were in nasal cavities that could not be examined at all by the 4 mm endoscope.

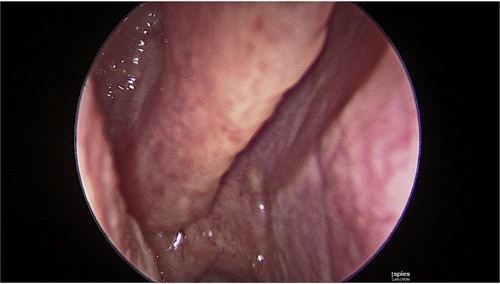

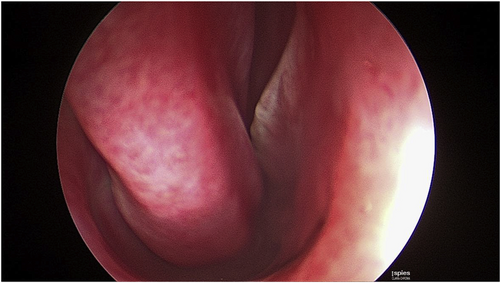

Discomfort experienced by patients correlated with the examiner's assessment of how difficult the endoscopy was (r = 0.73). The examiner found endoscopy with 4 mm endoscope more difficult than with the 3 mm endoscope, when comparing the paired endoscopy on each side (P = 0.027). The average score for overall difficulty of endoscopy was moderate, at 2.6 (range 1–4) on the scale of 1–5. No complications such as epistaxis or vaso-vagal attacks were noted in the study. Fig. 1 demonstrates a 3 mm endoscopic image capture, and Fig. 2 demonstrates a 4 mm endoscopic image capture with no further exam tolerated.

3 mm 30° nasal endoscopy.

4 mm 30° nasal endoscopy.

Discussion

Our study is limited by a small population size of 10 patients, and was fashioned as a study to compare 2 different diameter endoscopes available in our office for diagnostic nasal endoscopy.

Rigid nasal endoscopy was first employed over a century ago.1 Advancements in technology have permitted endoscopes of smaller diameters to be now widely available. Although one would intuitively assume that examination with a narrower endoscope would result in improved patient comfort, this was not noted on our study. Although we did not document patient discomfort according to which part of the nasal cavity was most uncomfortable on exam, most patients who expressed discomfort were observed to do so during examination of the spheno-ethmoid recess and the middle meatus. These were areas we were less likely to visualize with the 4 mm endoscope. Although the visualization of anatomic structures with the use of the 3 mm endoscope was better within the area of the spheno-ethmoid recess and middle meatus, this was likely at the cost of causing more discomfort due to the examiner's desire to push the limits for better visualization of structures in the field of view. Of note, two endoscopies with the 4 mm endoscope (10%) had to be prematurely terminated, one due to patient discomfort, and the other due to the examiner's inability to negotiate a severely deviated anterior septum. In both of these patients, endoscopic exam with the 3 mm endoscope could be performed satisfactorily. However, minor mucosal trauma was noted in both patients with the 3 mm endoscope.

Previous studies have evaluated the role of topical anesthesia in performing rigid nasal endoscopy in terms of visualization and patient comfort.5, 6 However, to our knowledge, no study has reviewed patient comfort based on diameters of the rigid nasal endoscope. The results of our study show that patients tolerate rigid nasal endoscopy with topical anesthesia in the office fairly well, with a low discomfort level of 2.65 (scale of 1–10). All of our endoscopies were performed following topical sprays of 1% phenylephrine and 4% lidocaine spray. No complications such as hemorrhage or vaso-vagal attacks were noted.

No patients underwent any previous sinus surgery. We were able to localize an accessory maxillary ostium in one patient, and were unable to see the natural maxillary ostium on any endoscopy. The inability to visualize the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus on any endoscopy reinforces an anatomical concept that any maxillary ostium seen in un-operated patients is likely an accessory ostium. We also could not visualize the frontal recess, suprabullar recess or retrobullar recess in any patient.

The 3 mm rigid endoscope was superior in visualizing structures in the spheno-ethmoidal recess (superior turbinate, sphenoid ostium) and can be useful in diseases isolated to that area. In a period where operative and office based balloon dilatations of the sphenoid ostium are being increasingly performed, the 3 mm endoscope may be particularly helpful.7 Visualization of the cribriform area was also superior with the 3 mm rigid endoscope. This would be useful in evaluating disorders of olfaction, as well as skull base lesions and defects such as in cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Improved visualization of the valve of Hasner and the inferior meatus was also noted, with potential applicability in visualizing scarring or previous inferior meatal antrostomies in these areas.

Patient discomfort correlated the examiner's perception of how difficult the nasal endoscopy was (r = 0.73). This correlation may be true, or confounded by the fact that a patient expressing discomfort is likely to affect the examiner's perception of difficulty. The examiner found endoscopy with the 4 mm endoscope more difficult than the 3 mm endoscope, when comparing the paired endoscopy on each side (P = 0.027). However, this difficulty with the 4 mm endoscope could also be secondary to examiner bias. The average score for overall difficulty of endoscopy was average at 2.6 (range 1–4) on the scale of 1–5.

Of note, the length of the 3 mm endoscope was shorter (14 cm) compared to the 4 mm endoscope (18 cm). We did not assess whether this difference affected visualization, patient comfort or examiner ease. No attempt was also made to compare difference in durability of the different endoscopes.

Conclusions

The 3 mm 30° rigid endoscope was superior in visualizing certain areas on nasal endoscopy as compared to the 4 mm endoscope. This included the sphenoid ostium, superior turbinate, spheno-ethmoid recess, uncinate process, cribriform plate, and valve of Hasner. The overall experience of patients on rigid nasal endoscopy showed good tolerance and a low discomfort level. No complications were noted during these diagnostic nasal endoscopies with either endoscope. The examiners determination of a difficult nasal endoscopy correlated with the level of discomfort experienced by the patient. Although patient discomfort was not significantly different for the two endoscopes, discomfort with 3 mm endoscopes was mostly noted during examination of structures that were less commonly visualized with the 4 mm endoscope. The smaller 3 mm endoscope can also be used for endoscopy in situations such a severely deviated septum where the larger 4 mm endoscope cannot be used at all. Patient discomfort correlated with examiner's assessment of difficulty. The 3 mm rigid endoscope therefore may be useful in assessment of spheno-ethmoid recess, nasolacrimal duct, and cribriform area pathologies (e.g. tumor, fungus ball, scarring, inflammation, anosmia, cerebrospinal rhinorrhea). It may also have some applicability in newer procedures such as office based sphenoid sinuplasty.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.