Factors related with the ability to maintain wakefulness in the daytime after fast and forward rotating shifts

Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore changes in cognitive function, sleep propensity, and sleep-related hormones (growth hormone, cortisol, prolactin, and thyrotropin) and to investigate the factors related to the ability to maintain wakefulness in the daytime after one block of fast forward rotating shift work (2 days, 2 evenings, and 2 nights). Twenty female nurses (mean age: 26.0 ± 2.0 years; range: 22–30 years) were recruited from an acute psychiatric ward. The nurses completed the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT), State Anxiety Inventory (SAI), Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS), Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Symbol Searching Test, Taiwan University Attention Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), and Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) four times throughout the day at 2-hour intervals, and their hormone levels were measured at the same time. There was no time of day effect on sleep propensity as measured by the MWT or MSLT despite an increase in self-reported sleepiness. Anxiety state and neuropsychological tasks, including executive function, attention, and perceptual and motor abilities were not affected during the daytime sleep restriction period. The number of omissions and perceptual and motor abilities showed a practice effect. The thyrotropin levels were significantly elevated, and cortisol levels significantly decreased during the daytime sleep restriction period. There were no significant changes in growth hormone or prolactin throughout the daytime period. Age was negatively associated with the mean sleep latency (MSL) of the MWT and positively associated with the MSL of the MSLT. The perseverative errors in WCST and SSS scores were negatively associated with the MSL of the MWT. SAI scores and thyrotropin levels were positively associated with the MSL of the MWT. In conclusion, there was no change in sleep propensity in the daytime after one block of rotating shift work. An attempt to preserve daytime alertness was also related to maintaining neuropsychological performance. Maintaining this ability was related to thyrotropin and age, and this cognition required a high attentive load.

Introduction

Shift work schedules in the medical field vary depending on a variety of conditions, including timing and length of work hours (e.g., 8-hour shifts or 12-hour shifts), fixed or rotating scheduling, duration and direction of rotation, and number of consecutive days of night work. The slower rotation used in the United States permits a worker to gradually adjust their circadian rhythm over a period of 2–4 weeks. Faster rotations (changing every 3–5 days) are popular in Europe and Japan, where it is assumed that workers will maintain constant circadian rhythms in co-ordination with the environment [1]. A three-shift system with faster rotation is common in the medical field in Taiwan, where nurses have 1 day off between the end of consecutive night shifts and the beginning of the next daytime shift. During the daytime of the off day, the nurses are expected to overcome the feelings of physical and/or mental tiredness and to be able to readjust their circadian rhythm.

Sleep deprivation studies [2] have shown a diverse impact on mood, cognitive performance, and motor function owing to an increase in sleep propensity and destabilization of the wake state. Specific neurocognitive domains, including psychomotor vigilance tasks, sustained attention tasks, and executive function, have shown to be particularly vulnerable to sleep loss [2], [3]. The effects of sleep restriction on cognitive performance in healthy adults are consistent with the effects of sleep restriction on physiological sleep propensity measures (Maintenance of Wakefulness Test, MWT; Multiple Sleep Latency Test, MSLT) [4], [5]. Many studies have investigated the influence of night shifts on night performance or the effects of partial or total sleep deprivation on cognitive function in a laboratory setting. However, little information is available on the ability of nursing staff to remain alert during the daytime after completing consecutive night shifts.

The work schedule of most nursing staff in our hospital consists of repetitive blocks of two consecutive day shifts (8 am to 4 pm or 8 am to 5:30 pm), two evening shifts (4 pm to 12 am), two night shifts (12 am to 8 am), followed by at least 1 day off. Using this three-shift system with fast forward rotation, we investigated changes in cognitive function and objectively measured sleep propensity in the daytime after one block of rotating shifts. We also measured levels of sleep-related hormones (growth hormone, GH; cortisol; prolactin, PRL; thyrotropin, TSH) during the daytime. Furthermore, we investigated the predictive factors related with sleep latency in the MSLT and MWT.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

Twenty female nurses (mean age: 26.0 ± 2.0 years; range: 22–30 years; years of education: 14.0 ± 2.9 years) were recruited from the acute ward of Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital, which is the largest psychiatric center in southern Taiwan. The exclusion criteria were the current use of hypnotics, regular drinking of coffee, psychiatric illness, major systemic disease, and sleep disorders. All participants had worked daytime shifts, evening shifts, or were free of duty for at least 3 days prior to starting the night shift. All individuals were asked to sleep prophylactically between 7 pm and 11 pm. Demographic data including age, mean self-reported total sleep time, and years of education were recorded.

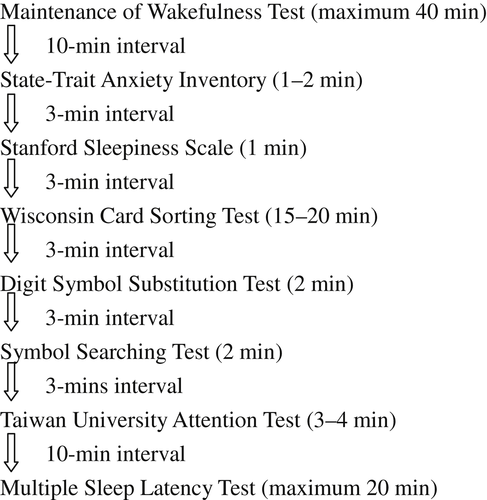

The participants arrived at the sleep laboratory at about 9:00 am at the end of a night shift, and spent about 8 hours in the laboratory. After application of the electrodes, the participants completed the following tests: MWT, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), Symbol Searching Test (SST), Taiwan University Attention Test (TUAT), and the MSLT. In addition, blood samples were collected and tested for cortisol, PRL, GH, and TSH. Each test was performed four times every 2 hours starting at 9:20 am. The participants may have been able to microsleep during the MSLT, and this may have been a confounder for the neuropsychological examinations. We, therefore, arranged the MWT prior to the MSLT and a series of tests between them to prevent an order effect. The procedure of the measurements is shown in Fig. 1. Blood samples were collected at the end of the MSLT at the bedside. All participants were required to remain awake during the test day, and all of the tests were given individually in an equivalent experimental setting. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to participation in the study, which was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital.

Procedure of measurements.

Measurements

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [6]: The STAI is a self-reported measure of both state and trait anxiety. Each inventory contains 20 self-reported items. State anxiety indicates a transitory condition of perceived tension to assess “How you feel right now, that is, at this moment,” and trait anxiety indicates a relatively stable condition of anxiety proneness to assess “How you generally feel”. All items are rated on a 4-point scale (range: 20–80 points) with a higher score indicating a higher anxiety. The STAI has been shown to have good validity and responsiveness as well as good internal consistency (Cronbach α higher than 0.85) and test–retest reliability (equal to or higher than 0.75) [7]. We used the State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) in this study.

Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS) [8]: The SSS is a 7-point self-rating scale that is used to quantify progressive steps in sleepiness, from 1 (alert) to 7 (no longer fighting sleep).

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) [9]: The WCST can be considered a measure of “executive function” requiring the ability to develop and maintain an appropriate problem-solving strategy across changing stimulus conditions in order to achieve a future goal [10]. The computerized WCST consists of four stimulus cards and 128 response cards that depict figures of varying form, color, and number. The participant is instructed to match each consecutive card from the deck with one of the four stimulus cards that he or she thinks it matches. The number of perseverative errors, number of total errors, number of categories, percent of conceptual level responses, and failure to maintain set were used as dependent variables.

Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) and Symbol Searching Test (SST): These tests are subsets of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [11] involving cognitive, perceptual, and motor abilities. In the DSST, participants were asked to enter the appropriate symbols into empty squares beneath digits. In the SST, individuals were asked to respond to either one of two target symbols presented with four selective symbols. Both the DSST and SST raw scores were determined by the number of items correctly completed in 120 seconds; then the raw score was transformed to a scale score according to age. The information process index (IPI) was obtained after converting the sum of the scale scores of the SST and DSST.

Taiwan University Attention Test (TUAT): The TUAT [12] requires participants to cross out as fast and as accurately as possible two target characters from a random list of 780 letters, numbers, and symbols printed on an A4 sheet of paper. The number of characters/second (the number of omissions subtracted from the correct number of characters divided by the time taken to complete the test), number of omissions, and completion time were used as the dependent variables.

The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): Partial-montage polysomnography was performed, which consisted of electroencephalography (at F3/A2, F4/A1, C4/A1, C3/A2, O2/A1, O1/A2), electrooculography, and submental electromyography. We scored sleep records visually in 30-second epochs according to the American Academic of Sleep Medicine criteria [13]. Sleep latency was recorded with the participants lying in a quiet, dark bedroom and attempting to fall sleep. The individuals were awoken immediately after three consecutive 30-second epochs of stage 1 sleep or any epoch of another sleep stage. The score was taken as the latency to the first epoch of any stage of sleep. If sleep onset did not occur, a latency of 20 minutes (the end of the test) was used for data analysis.

The Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT): This test is administered in a similar method to the MSLT. The major distinctions are that in the MWT the participants were instructed to remain awake, and the termination criterion was 40 minutes.

The serum levels of cortisol, PRL, GH, and TSH were measured by a paramagnetic particle, chemiluminescent immunometric assay using a Beckman Access system (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA), Siemens DPC Immulite 2000 analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostic Products Ltd., Llanberis, Gwynedd, UK), Siemens DPC Immulite 2000 analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostic Products Ltd.), and Abbott I2000 (Abbott Ireland Diagnostics Division, Longford, Ireland), respectively. The intra-assay coefficient of variation averaged 5% in each item.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the data for each time series. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) linear regression models were used with time of day as the categorical variable. Age and education years, and hormone level and neuropsychological variables were used as covariates to investigate the possible predictors regarding the latency of MWT and MSLT, respectively. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean self-reported total sleep time during study night shifts was 6.6 ± 1.1 hours. There was no significant time of day effect on mean sleep latency in the MWT and MSLT, although there was significantly increased subjective sleepiness in the SSS scale (Table 1). Neuropsychological analysis revealed a significant time of day effect on the number of omissions in the TUAT, IPI, and DSST and SST scores. All of these variables showed a trend of improved performance during the daytime. There were no significant changes throughout the daytime in the completion time and the number of characters/second in TUAT performance, all parameters of the WCST and SAI scores (Table 1). With regard to hormone measurements, levels of TSH were found to be significantly elevated and levels of cortisol were significantly decreased; however, there were no significant changes in the levels of PRL and GH throughout the daytime (Table 1).

| Variables (mean ± SD)∗ | Morning time 1 (1) | Morning time 2 (2) | Afternoon time 1 (3) | Afternoon time 2 (4) | F(3,57) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency of MWT | 17.0 ± 13.1 | 22.1 ± 15.1 | 18.8 ± 12.9 | 16.3 ± 14.8 | 1.178 | 0.326 |

| Sleep latency of MSLT | 10.0 ± 6.3 | 8.3 ± 6.1 | 8.0 ± 6.3 | 7.4 ± 5.2 | 1.397 | 0.253 |

| State anxiety scale | 42.5 ± 8.0 | 43.6 ± 7.4 | 43.4 ± 7.3 | 42.2 ± 7.7 | 0.612 | 0.610 |

| SSS | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 4.774 | 0.005 |

| WCST | ||||||

| Number of PEs | 12.1 ± 6.9 | 11.5 ± 6.4 | 12.1 ± 7.3 | 12.8 ± 11.0 | 0.377 | 0.770 |

| Number of total errors | 24.7 ± 14.0 | 22.4 ± 12.0 | 23.0 ± 12.5 | 24.0 ± 13.7 | 0.908 | 0.443 |

| Number of categories | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 8.4 ± 2.2 | 8.2 ± 2.3 | 8.1 ± 2.2 | 0.584 | 0.628 |

| % of CLRs | 76.7 ± 15.7 | 79.4 ± 13.1 | 78.8 ± 15.0 | 77.6 ± 14.8 | 0.964 | 0.416 |

| Failure to maintain set | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0.595 | 0.621 |

| TUAT | ||||||

| Time (s) | 215.4 ± 50.5 | 216.4 ± 42.5 | 210.5 ± 34.5 | 209.2 ± 30.6 | 1.122 | 0.349 |

| Number of omissions | 7.6 ± 4.6 | 6.2 ± 4.1 | 5.3 ± 4.2 | 5.0 ± 4.4 | 5.010 | 0.004 |

| Number of characters/s | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.990 | 0.126 |

| DSST | ||||||

| Scoring scale | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 14.0 ± 2.7 | 14.4 ± 2.8 | 14.4 ± 2.9 | 2.957 | 0.040 |

| SST | ||||||

| Scoring scale | 13.3 ± 3.2 | 13.8 ± 2.4 | 14.4 ± 3.1 | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 4.520 | 0.007 |

| IPI | 118.0 ± 14.6 | 121.6 ± 13.2 | 124.6 ± 14.7 | 126.0 ± 13.7 | 6.258 | 0.001 |

| PRL level (ng/mL) | 11.8 ± 6.0 | 12.5 ± 7.0 | 13.4 ± 7.0 | 14.9 ± 6.6 | 2.442 | 0.073 |

| GH level (ng/mL) | 1.4 ± 3.0 | 1.0 ± 1.6 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 2.4 | 1.573 | 0.206 |

| TSH level (mIU/L) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 9.966 | <0.001 |

| Cortisol level (ug/dL) | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 4.5 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 3.246 | 0.028 |

- CLRs = conceptual level responses; DSST = Digit Symbol Substitution Test; GH = growth hormone; IPI = Information Process Index; PEs = perseverative errors; PRL = prolactin; SSS = Stanford Sleepiness Scale; SST = Symbol Searching Test; TSH = thyrotropin; TUAT = Taiwan University Attention Test; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. ∗SSS: 1 < 3, 1 < 4, 2 < 3, 2 < 4 (p = 0.018, p = 0.009, p = 0.037, p = 0.050, respectively); Number of omissions: 1 > 3, 1 > 4, 2 > 4 (p = 0.028, p = 0.002, p = 0.027, respectively); DSST scoring scale: 1 < 2, 1 < 3 (p = 0.031, p = 0.012, respectively); SST scoring scale: 1 < 3, 1 < 4 (p = 0.005, p = 0.008, respectively); IPI: 1 < 3, 1 < 4 (p < 0.001, p = 0.003, respectively); TSH: 1 < 2, 1 < 3, 1 < 4, 2 < 3, 2 < 4 (p = 0.007, p = 0.005, p < 0.001, p = 0.047, p < 0.001, respectively); cortisol level: 2 > 3, 2 > 4 (p = 0.051, p = 0.016, respectively).

When the TSH levels were elevated, the performance on visual attentive tasks improved despite an increased subjective sleepiness as measured by the SSS. We then used GEE linear regression models, with time of day as the categorical variable, and TSH and cortisol levels, age, education years, and SSS scores as covariates, to estimate the dependent variables in terms of IPI, and DSST and SST scores. The results showed that TSH level was positively correlated with IPI and DSST scores (beta coefficient 2.08, p = 0.051; beta coefficient 0.33, p = 0.021), respectively.

With regard to latency on the MWT and MSLT, a fitted model obtained from GEE linear regression showed that age, SAI scores, SSS scores, perseverative errors of the WCST, and TSH level were possible predictors for the latency in the MWT. Age, SSS scores, and perseverative errors of the WCST were negative predictors, and SAI scores and TSH level were positive predictors for the latency in the MWT. Only age was a positive predictor for latency in the MSLT (Table 2).

| Model of latency of MWT | Beta coefficient | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −2.545 | 0.981 | 0.010 |

| State Anxiety Scale | 0.314 | 0.162 | 0.053 |

| Stanford Sleepiness Scale | −3.856 | 1.128 | 0.001 |

| Number of perseverative errors | −1.329 | 0.645 | 0.039 |

| TSH level | 4.259 | 0.196 | 0.040 |

| Model of latency of MSLT | |||

| Age | 0.749 | 0.340 | 0.028 |

- MSLT = Multiple Sleep Latency Test; MWT = Maintenance of Wakefulness Test; SE = standard error; TSH = thyrotropin.

- a The significance was determined by Wald χ2 test with df = 1.

Discussion

Our results showed that after working one rotating shift block following daytime sleep restriction, the nurses had no significant increase in sleep propensity as measured by the MWT and MSLT despite an increase in subjective sleepiness as measured by the SSS. In addition, the anxiety state and neuropsychological tasks, including executive function, attention, and perceptual and motor abilities were not affected by the daytime sleep restriction period. Furthermore, the number of omissions and perceptual and motor abilities showed a practice effect.

Latency in the MSLT reflects propensity to fall asleep during the daytime. Healthy individuals without emotional or sleep disturbances are often able to achieve Stage 1 sleep in a relatively short period of time (10 minutes according to the MSLT) when allowed to fall sleep in appropriate conditions [14]. Latency in the MWT reflects the quality of nighttime sleep. The better the nighttime sleep, the greater the daytime alertness as reflected in increased latency in the MWT [14]. Although our participants experienced daytime sleep restriction after two consecutive night shifts, this increased sleep debt was parallel to subjective sleepiness. However, the results showed that this did not affect sleep propensity when measured objectively.

Horne [15] showed that total sleep deprivation (32 hours) could cause impairment in higher cortical functions similar to that found in patients with frontal lobe dysfunction (although much less severe). Binks et al. [16] reported that one night of total sleep deprivation (34–36 hours) did not appear to impair performance on tasks that were designed to assess higher cortical functions (including the WCST). Our participants were assumed to have partial sleep deprivation (the mean self-reported total sleep time during the study night shifts was 6.6 ± 1.1 hours) for 2 days following total sleep deprivation for 17 hours. The ability to perform the WCST was maintained throughout the daytime after two consecutive night shifts, that is, the ability to shift cognitive strategies in response to changing environmental contingencies was not affected.

The ability to carry out visual attentive tasks in the present study was maintained during the daytime sleep restriction period; however, substantial differences between the tasks were observed. There was a significant time of day effect on improved performances in perceptual and motor abilities, while the number of characters/second and the TUAT completion time did not improve throughout the daytime. Even though the SST and DSST share similar cognitive and perceptual abilities with the TUAT, they seem to be more reliant on visual searching and perceptual motor coordination. However, the TUAT seems to be more complex and monotonous, thereby requiring a higher attentive load than the SST and DSST [17]. Therefore, there should be a practice effect reliant on perceptual visual-motor coordination tasks, which require a low attentive load in the daytime after two consecutive night shifts, thereby leading to a lack of a learning effect on monotonous repetitive visual attentive tasks that require a high attentive load.

We also applied the SAI to examine hyperarousal factors. Under a state of hyperarousal, participants were expected to underestimate the state of sleepiness and have impaired attention. Precipitating events (e.g., work stress and personal difficulties) are distinct elements for a state of hyperarousal [18]. There was no time of day effect on SAI scores throughout the daytime sleep restriction period in our study.

Our results revealed that the TSH level was significantly elevated and the cortisol level significantly decreased during the daytime sleep restriction period; however, there were no significant changes in GH and PRL levels.

The level of cortisol declines throughout the daytime from a peak in the early morning to a nadir in the late evening and early phase of nocturnal sleep. The level of TSH rises from a nadir in the daytime and then progressively increases towards the evening reaching a peak just prior to sleep onset [19]. Sleep loss appears to delay the normal return to evening quiescence of the corticotropic axis, resulting in increased cortisol levels the following evening compared with the previous evening [20]. Sleep deprivation causes an elevation of nocturnal TSH to about double the usual level, and this elevation persists during the daytime because of its prolonged half-life [21]. As no controls were used for comparison in this study, we were unable to investigate whether the serial decrease in cortisol and increase in TSH secretion throughout the daytime followed a normal physiological or exaggerated circadian pattern after two consecutive night shifts. GH and PRL secretion are linked to sleep and are only triggered by sleep onset regardless of time of day or sleep deprivation [19]. Our results revealed no significant changes in GH and PRL during the daytime, which is comparable with their physiological patterns.

According to the GEE linear regression models, the ability to remain awake decreased with increasing age and feeling of sleepiness. The perseverative errors in the WCST were negatively associated with the ability to remain awake as measured by the MWT. The increased SAI scores and elevated TSH levels were positively associated with the ability to remain awake. However, only age was positively associated with sleep propensity as measured by the MSLT. The elevated TSH levels were possibly associated with the improved performance visual attentive tasks.

No previous studies have discussed the age effect on wakefulness-promoting or sleep-promoting abilities. Our results showed that an increasing age, it was difficult to remain awake and to fall sleep as measured by the MWT and MSLT, respectively, in the daytime after consecutive night shifts. We hypothesize that age is an important factor in adjusting the circadian rhythm under a three-shift system with faster rotation. The subjective increase in feeling sleepy was not correlated with sleep latency in the MSLT; however, it was correlated with sleep latency in the MWT. Even though the capacity to maintain wakefulness is not directly related to physiological sleep tendency [14], [17], a study showed that individuals with low MSLT scores (i.e., greater readiness to fall asleep) were still able to stay awake on the MWT [14]. The sleep-restricted individuals in that study had an incentive to remain awake, which was reflected in the longer sleep latencies in the MWT but not reflected in physiological sleep tendency.

The perseverative errors of the WCST were negatively correlated with the ability to remain awake in our study. This finding can be explained by the relationship between the performance of executive function and the requirement of activating a wakefulness- promoting brain mechanism for a period of time.

Our results showed a tendency of a positive association between the SAI scores and sleep latency in the MWT. Emotional arousal will cause physiological activation, which can be measured by several physiological indices such as the MSLT and MWT. Under a state of hyperarousal, a lack of normal sleep would be expected both during the day and night [22]. In our study, the participants were instructed to maintain wakefulness after loss of sleep the previous night, resulting in increased emotional tension in the daytime, which was reflected by increased sleep latency in the MWT.

We also found that the TSH level was significantly elevated during the daytime sleep restriction period, and that it was associated with maintaining wakefulness. No previous study has discussed the relationship between TSH secretion and maintenance of wakefulness. Some studies have mentioned a relationship between hyperarousal (stress or emotional problems) and cortisol secretion [19], [23]. It is possible, therefore, that another mechanism of hyperarousal was responsible for our findings. We hypothesize that the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis instead of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may modulate the wakefulness-promoting brain mechanism, as revealed by the correlation of TSH secretion with the latency in the MWT. When the TSH levels were elevated, the performance on visual attentive tasks improved. This suggests a possible biological basis of visual attention ability under conditions of sleep restriction. This biological basis of attention performance regarding hormones will be an interesting topic for future studies.

There are some limitations to our study. First, there was a lack of baseline data regarding cognitive tests and daytime sleep during the night shift periods, and this could have confounded the results. Second, we did not use indwelling catheters to avoid pain when collecting blood samples, nor did we record the stage of menstrual cycle that may have been related to the PRL level. These could also have been the confounding factors. Third, the tasks were conducted in an experimental setting, and the neuropsychological findings in this study cannot be generalized to real-life practice. Fourth, we did not use controls for comparisons. Fifth, not all participants had the same shift work schedule prior to entering the study night shift schedule, which may have confounded the results.

In conclusion, the individuals working one block of a rotating shift following daytime sleep restriction had no changes in sleep propensity as measured objectively. An attempt to preserve daytime alertness was also related to maintaining neuropsychological performance. Maintaining this ability was related to TSH and age, and this cognition required a high attentive load.