Inappropriate mode switching clarified by using a chest radiograph

Abstract

An 80-year-old woman with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and atrioventricular node disease status post-dual chamber pacemaker placement was noted to have abnormal pacing episodes during a percutaneous coronary intervention. Pacemaker interrogation revealed a high number of short duration mode switching episodes. Representative electrograms demonstrated high frequency nonphysiologic recordings predominantly in the atrial lead. Intrinsic pacemaker malfunction was excluded. A chest radiograph showed excess atrial and ventricular lead slack in the right ventricular inflow. It was suspected that lead–lead interaction resulted in artifacts and oversensing, causing frequent short episodes of inappropriate mode switching.

1 Case Report

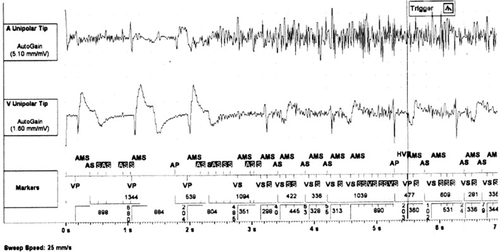

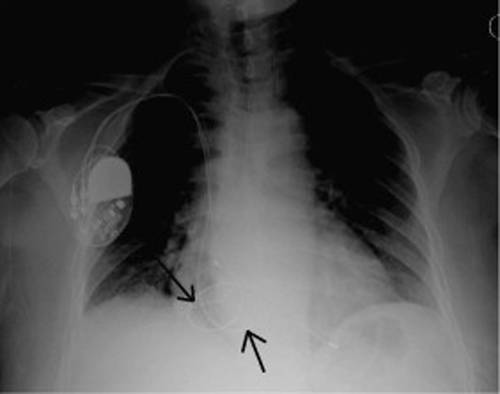

An 80-year-old woman with underlying coronary artery disease, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and atrioventricular nodal disease status post pacemaker placement was noted to have episodes of abnormal pacing during an elective coronary angiogram and percutaneous coronary intervention. She had not experienced any palpitations or syncope. Five years previously, the patient had undergone placement of St. Jude (Sylmar, CA, United States) dual-chamber Victory XL Model 5816 pacemaker at another institution for symptomatic bradycardia. Pacemaker interrogation revealed an unusually high number (over 9000 episodes) of mode switching (DDDR-DDIR with detection rate 180 beats per minute). All these episodes lasted <30 s and the total burden was 1.3%. Analysis of the electrogram (Fig. 1) from a representative event demonstrated very high frequency nonphysiologic recordings (750–1000 bpm), predominantly in the atrial lead, but in both leads simultaneously. The intrinsic P wave was 2.6 mV, and sensitivity was set at 0.5 mV. Atrial lead impendence was 485 Ω and had not recently changed, making lead fracture or dislodgement unlikely as a potential cause. Pocket manipulation, as well as directed positional changes in the patient, failed to reproduce any of the artifacts. Review of the chest radiograph (Fig. 2) demonstrated both the atrial and ventricular leads had significant excess slack overlapping in the right ventricular inflow tract. It is suspected that lead–lead interaction in this area resulted in artifacts and oversensing. The patient will require generator replacement within the next 6 months owing to normal battery depletion. As the patient was not having bradycardia-related symptoms and was not pacemaker dependent, plans were made to revise the leads at the time of generator change.

Pacemaker interrogation with atrial lead showing nonphysiologic electrical activity leading to inappropriate mode switching. Also, note some lesser simultaneous artifacts in the ventricular lead.

Chest radiograph showing ventricular lead coiling in the right atrium (downward pointing arrow) before entering the right ventricle. Upward pointing arrow shows the atrial lead that coils through the tricuspid valve and into the right ventricle prior to implantation into the right atrium.

2 Discussion

A sensed atrial high rate episode (AHRE) triggers mode switching in contemporary dual chamber pacemakers to prevent tracking of an atrial tachyarrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia at high ventricular rates. Mode switching has eliminated the relative contraindication of a dual chamber pacing device in patients with paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias and has proven to increase both exercise time as compared to VVIR and quality of life as compared to VVIR or DDDR without mode switching [1]. More recently, an association of increased stroke risk with asymptomatic AHRE with a detection limit of >190 beats per minute (i.e. subclinical atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter) as evaluated in the ASSERT trial, has further elevated the importance of mode switching [2]. IMPACT, a large multicenter randomized anticoagulation intervention trial in patients with AHRE, is anticipated to be completed in 2014 [3]. The St. Jude Auto Mode Switch (AMS) algorithm is activated when filtered atrial rate interval (FARI) or the mean atrial rate exceeds the set atrial tachycardia detection rate (ATDR). Usually, mode switching triggered by the above mechanism infers the presence of an atrial tachyarrhythmia although the detection can be subject to error. Erroneous mode switching may be due to oversensing of near-field P waves, far-field R waves, or less commonly by VA conduction leading to AV desynchronization arrhythmia [4]-[6]. Oversensing with inappropriate mode switching has also been described with skeletal muscle myopotential activity and oversensing impedance pulse due to a loose conductor ring screw set [7], [8]. Clinically, lowering atrial sensitivities to ignore electrical activity not coming from the atria or extending the post ventricular atrial blanking (PVAB) period at a fixed interval to avoid crosstalk and retrograde atrial recognition often alleviates oversensing. Although algorithms and technology continue to improve accurate atrial tachyarrhythmia detection, a review of available representative electrograms is advised not only to determine which atrial tachyarrhythmia is present, but also to verify accuracy [9], [10]. In our case, the supraphysiologic rate demonstrated on the electrogram was clearly attributed to an artifact (Fig. 1), effectively eliminating many of the previously described causes of inappropriate mode switching. Simultaneous artifacts in both leads strongly suggested a lead–lead interaction as the cause of the arrhythmia. Chest radiographs in the context of cardiac implantable electronic devices are often reviewed to evaluate for lead integrity and placement. In this patient, the chest radiograph readily revealed the likely cause of oversensing. It should be noted that concurrent insulation breach, even with stable impedance, cannot be ruled out as contributing to the simultaneous artifacts in one or both leads at the time of lead–lead interaction.

3 Conclusion

A review of the chest radiograph is advised in a case of inappropriate mode switching when the atrial electrogram reveals a nonphysiologic etiology.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest for the published content.