Left atrial thrombus formation and resolution during dabigatran therapy: A Japanese Heart Rhythm Society report

Abstract

Background

Protocols on the use of novel oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) undergoing electrical cardioversion (ECV) are lacking.

Aim

The study was aimed at evaluating the efficacy of dabigatran (Dabi) treatment in preventing peri-ECV stroke.

Methods

A retrospective survey of the incidence and fate of left atrial (LA) thrombus during Dabi therapy in patients with AF was conducted between December 2012 and January 2013 by the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society.

Results

A total of 198 patients from 299 institutions underwent transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to rule out LA thrombus before ECV. Of these, LA thrombus was found in eight patients (4%), who tended to be older (67.3 vs. 61.3 years, p=0.175), had higher CHADS2 scores (1.88 vs. 0.95, p=0.058), and a higher prevalence of prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (22.2% vs. 2.6%, p=0.034) than those without LA thrombus. Of the eight patients with LA thrombus, one had LA thrombus during a Dabi 150 mg b.i.d treatment, whereas the remaining seven were receiving 110 mg b.i.d for 3 weeks or longer. In 6 of the 8 patients with LA thrombus, a second TEE was performed, revealing complete resolution of LA thrombus in five; among these five patients, one received Dabi dosage of 150 mg b.i.d unchanged, two received an increased dosage from 110 mg to 150 mg b.i.d, and two were switched to warfarin. Two patients had a stroke 3 and 15 days after ECV, and one had a major large intestine bleeding episode during Dabi therapy.

Conclusions

LA thrombus developed in 4% of patients with AF receiving Dabi. Older patients with a higher CHADS2 score receiving a lower Dabi dosage were more likely to develop LA thrombus, which was resolved with a prolonged or increased dosage. A higher Dabi dosage may be more beneficial before ECV but prospective randomized studies would be needed to confirm these results.

1 Introduction

Stroke prevention is of prime importance in the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Although the risk of thromboembolic stroke is predicted by a variety of factors, including those indicated by the CHADS2 score, electrical cardioversion (ECV) is a special situation where this risk increases temporarily.

Warfarin administration is recommended for at least 3 weeks and 4 weeks before and after elective ECV, respectively, unless the possibility of left atrial (LA) thrombus is excluded by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) [1]-[4]. However, the validity of this approach for the use of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is unknown.

Since dabigatran (Dabi) was first introduced in clinical practice on March 14, 2011 in Japan, ECV has been performed during Dabi therapy, providing an opportunity to examine both LA thrombus formation and resolution in patients with AF. Accordingly, the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society (JHRS) conducted a survey of the incidence and the fate of LA thrombus.

2 Materials and methods

A retrospective questionnaire survey was conducted among 299 JHRS institutions from December 2012 to January 2013. Patients with persistent AF who underwent TEE for elective ECV were included. LA thrombus incidence, risk factors for thrombus formation as indicated by the CHADS2 score, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, Dabi dosage (110 mg b.i.d or 150 mg b.i.d), treatment duration before ECV (<3 weeks, 3–6 weeks, ≥6 weeks) and after ECV (<4 weeks, ≥4 weeks), and co-administration of amiodarone or verapamil were examined. Patients with LA thrombus underwent repeated TEE to determine LA thrombus fate and the possibility of thrombus resolution. Furthermore, embolic as well as hemorrhagic complications occurring in patients without LA thrombus were evaluated within 1 month of ECV while on Dabi.

Comparisons between patients with and without LA thrombus were made using a Student t-test for age and a chi-square test for other variables.

3 Results

3.1 LA thrombus prevalence

A total of 198 patients underwent TEE to rule out the presence of LA thrombus before ECV. The average age was 61.6 years with an 84% male predominance. The average CHADS2 score was 0.99 with 3.5% of patients having a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Dabi 150 mg b.i.d and 110 mg b.i.d were given to 98 and 100 patients, respectively. LA thrombus was found in one patient receiving the higher dosage while seven patients received the lower dosage (p=0.076) (Table 1). The decision to administer the lower dosage in 58% of patients was based on Japan's recommendations, which requires the fulfillment of one of the following criteria: creatinine clearance rate, 30–50 mL/min; co-administration of p-glycoprotein inhibitors such as amiodarone or verapamil; age ≥70 years; or a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. In the remaining 42% of patients, physicians arbitrarily selected the lower dosage.

| LA thrombus (−) | LA thrombus (+) | Total | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 190 | 8 | 198 | ||

| Age (yrs; mean±SD) | 61.3±12.0 | 67.3±12.7 | 61.6±12.1 | p=0.175 | |

| Male (n) | 160 | 7 | 167 | ||

| CHADS2 score (mean) | 0.95 | 1.88 | 0.99 | p=0.058 | |

| 0 or 1 (n) | 141 | 3 | 144 | ||

| 2 (n) | 29 | 4 | 33 | ||

| 3–6 (n) | 14 | 1 | 15 | ||

| Unknown (n) | 6 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Prior stroke/TIA (n) | 5 | 2 | 7 | p=0.034 | |

| 150mg b.i.d | 97 | 1 | 98 | p=0.076 | |

| 110mg b.i.d | 93 | 7 | 100 | ||

| As recommended* | 54 | 4 | 58 |

- * Dose reduction to 110 mg b.i.d according to Japan's recommendations described in the text.

Dabi was administered for <3 weeks in 21%, for 3–6 weeks in 24%, and for ≥6 weeks in 55% of patients prior to TEE.

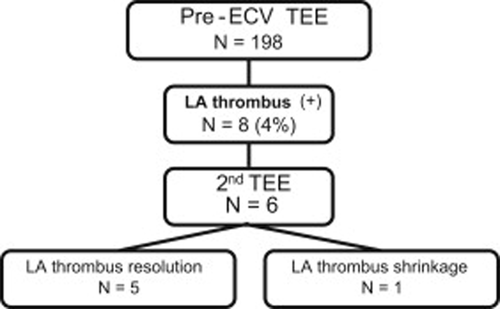

3.2 Characteristics of LA thrombus patients

LA thrombus was found in eight (4%) out of 198 patients (Fig. 1). The eight patients with LA thrombus tended to be older (67.3 vs. 61.3 years, p=0.175), had higher CHADS2 scores (1.88 vs. 0.95, p=0.058), and had a higher prevalence of prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (22.2% vs. 2.6%, p=0.034) than those without LA thrombus (Table 1).

Summary of serial TEE findings. ECV, electrical cardioversion; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; LA, left atrial.

Of the eight patients with LA thrombus, one was receiving a Dabi dosage of 150 mg b.i.d, whereas the remaining seven were receiving 110 mg b.i.d for ≥3 weeks. Notably, in three of these seven patients, the dosage of 110 mg b.i.d was arbitrarily selected and did not reflect the Japanese recommendations for dosage reduction as described in Section 3.1.

3.3 LA thrombus fate

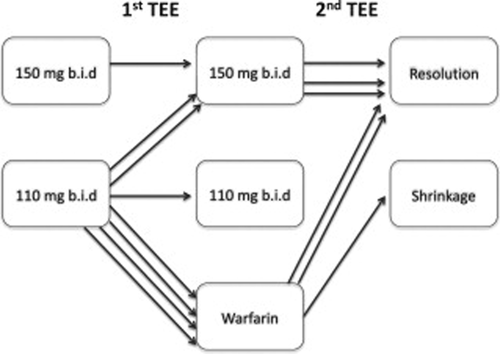

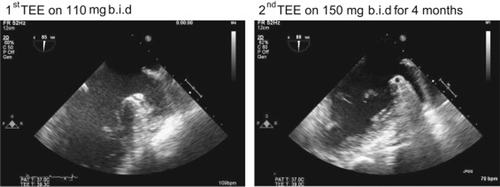

A second TEE was performed in six of the eight patients with LA thrombus, which revealed complete resolution of the thrombus in five patients with the earliest resolution within 23 days after the first TEE (Fig. 1). Of these five patients, one was receiving a prolonged Dabi dosage of 150 mg b.i.d, two had an increase in dosage from 110 mg to 150 mg b.i.d, and the remaining two were switched to warfarin (Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3). One patient undergoing the second TEE 9 days after warfarin therapy only showed LA thrombus shrinkage.

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | Wt (kg) | CLcr (mL/m) | CHADS2 score | Dabi dosage (mg, b.i.d) | Wks of Dabi prior to 1st TEE | 2nd OAC for LA thrombus | Days to 2nd TEE | Fate of LA thrombus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 82 | M | 68 | 64 | 4 | 110* | 3–6 | 110 | – | Unknown |

| 2 | 63 | M | 83 | 77 | 2 | 110 | ≧6 | Warfarin | 23 | Disappeared |

| 3 | 70 | M | 52 | 55 | 2 | 110* | ≧6 | 150 | 58 | Disappeared |

| 4 | 78 | M | 90 | 66 | 2 | 110* | ≧6 | Warfarin | – | Unknown |

| 5 | 82 | M | 41 | 42 | 2 | 110* | ≧6 | Warfarin | 9 | Shrank |

| 6 | 49 | M | 96 | 154 | 1 | 110 | ≧6 | 150 | 121 | Disappeared |

| 7 | 58 | M | 61 | 89 | 1 | 150 | ≧6 | 150 | 308 | Disappeared |

| 8 | 56 | F | 81 | 100 | 1 | 110 | ≧6 | Warfarin | 49 | Disappeared |

- * Dose reduction to 110 mg b.i.d according to Japan's recommendations described in the text.

Fate of left atrial thrombus in the eight patients. TEE, transesophageal echocardiography.

Left atrial (LA) thrombus resolution demonstrated on serial TEE in one patient. A small thrombus is shown in the LA appendage during Dabi treatment with 110mg bid (left).

3.4 ECV complications

ECV was carried out in both 190 patients without LA thrombus and in five patients after LA thrombus resolution. ECV was not attempted in the three remaining patients with no LA thrombus resolution confirmation by TEE. Two patients (1%) had a stroke at days 3 and 15 after ECV while on Dabi 110 mg b.i.d, although LA thrombus was not detected before ECV. The former patient had CHADS2 score zero, but received a lower dosage of 110 mg b.i.d arbitrarily selected by a physician, and the latter was an 83-year-old patient with hypertension. A 68-year-old male diabetic patient receiving a Dabi dosage of 110 mg b.i.d had a major large intestine bleeding episode secondary to colon carcinoma and required hospitalization.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

LA thrombus developed in 4% of patients with AF despite Dabi administration before elective ECV, as shown on TEE. Older patients with higher CHADS2 score, an inappropriately Dabi lower dosage, or a shorter treatment duration appeared to be more susceptible to LA thrombus formation. LA thrombus resolution was achieved typically after an increase in Dabi dosage or switching to warfarin. Finally, although peri-ECV thromboembolic complications were rare, they occurred despite the previous absence of LA thrombus.

LA thrombus formation in AF patients receiving NOAC treatment has not been studied extensively. Although modalities to examine LA thrombus such as computed tomography or intracardiac echocardiography exist, TEE is by far the most popular and reliable method being used in clinical practice [3], [4]. However, because of its invasive nature, TEE is indicated only in patients undergoing ECV or AF ablation to exclude the presence of LA thrombus before the procedure. This survey has thus provided an opportunity to ascertain LA thrombus prevalence among patients with persistent AF selected to undergo elective ECV.

4.2 LA thrombus development during warfarin therapy

This survey demonstrated the presence of LA thrombus in 4% of patients with AF despite all receiving anticoagulant therapy with Dabi for at least 3 weeks. Although it may not be appropriate to compare this result with those of previous studies using warfarin, a single-center study in Germany including 799 patients with persistent AF receiving warfarin for at least 3 weeks and with a prothrombin time–international normalized ratio (PT–INR) between 2 and 3 detected LA thrombus using TEE in 7.7% [5]. In that study, thromboembolic events developed within 4 weeks of ECV at a rate of 0.8% in both groups of patients receiving the TEE guided and non-guided conventional approach, indicating that LA thrombus, even if present, may not necessarily be dislodged to cause thromboembolic events occurring after ECV. Although the prevalence of LA thrombus has been variable depending on the subjects studied, it was 4% if TEE was performed within 48 h of AF without prior anticoagulation [6]. ECV without oral anticoagulant therapy was previously accepted in patients with <48 h of AF [7]. However, a recent Finnish study demonstrated that even in this set of patients, the risk of thromboembolic events can reach up to 9.8% among those with both heart failure and diabetes [8]. On the other hand, LA thrombus prevalence was reported to be 3% in the above-mentioned German study when TEE was performed in 295 low-risk patients with AF with a CHADS2 score of 0 or 1 [9]. LA thrombus prevalence or sludge increases with increasing scores of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc [10], [11]. Therefore, it was not surprising that in our survey, patients with LA thrombus tended to be older and had a higher CHADS2 score and prevalence of previous stroke or transient ischemic attack than those without demonstrable LA thrombus.

4.3 LA thrombus development during NOAC use

Although Dabi appears to be an effective alternative to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism without requiring PT–INR monitoring, the fact that 4% of patients receiving Dabi still had LA thrombus in our survey suggests that TEE is useful when performed before elective ECV of persistent AF. Thrombus may develop even under Dabi treatment in the presence of mechanical heart valves or rheumatic mitral stenosis [12], [13], but a few cases of failure to prevent LA thrombus formation with the use of this agent have also been reported in patients with AF without such backgrounds [14]-[16]. Although it is hard to prove, we speculate that not only higher CHADS2 scores, but also the insufficient Dabi dosage given to some of our patients might have led to inadequate anticoagulation and subsequent clot formation. Three of the seven patients taking this lower dosage did not fulfill any of the recommendation criteria for using a 110 mg b.i.d dosage, but whether a 150 mg b.i.d dosage could have prevented LA thrombus formation in these patients remains uncertain.

In the RE-LY study, where TEE was performed according to physicians' preference, LA thrombus was detected in 1.8% of 165 patients and in 1.2% of 162 patients receiving 110 mg b.i.d and 150 mg b.i.d dosage, respectively [17]. Although the results of the RE-LY study were in line with ours, we observed a higher incidence of LA thrombus at the lower Dabi dosage, which could be a reflection of shorter anticoagulation duration as well as a potentially lower patient adherence to Dabi treatment, in a real-world scenario. Dabi treatment adherence was not carefully evaluated in this survey, but poor adherence in some patients could have been responsible for inadequate anticoagulation. As LA thrombus can develop in a substantial number of patients receiving Dabi, we recommend TEE for every ECV candidate, but whether this also applies to other NOACs remains uncertain. Peri-ECV complication sub-analysis in prospective studies yielded variable stroke or systemic embolism rates of 0.8% and 0.3% at Dabi dosages of 110 mg and 150 mg b.i.d in the RE-LY study, respectively, 1.8% with rivaroxaban in the ROCKET AF study, and 0% with apixaban in the ARISTOTLE study 30 days after ECV [18], [19]. A recent prospective randomized trial comparing rivaroxaban and vitamin K antagonists for AF cardioversion failed to show any significant difference in the primary efficacy and safety outcomes [20]. However, in a small patient subgroup where TEE was performed optionally, LA thrombus was found in six out of 33 patients versus zero out of 31 patients receiving rivaroxaban or vitamin K antagonists, respectively, for 3–8 weeks prior to ECV.

4.4 Stroke after negative TEE

In our study, two patients (1%) had a stroke after ECV. Although not every preexisting LA thrombus might cause thromboembolism after ECV, stroke incidence could have been higher if ECV had been performed without prior TEE. However, it is noteworthy that TEE was not able to detect LA thrombus in any of these two patients before ECV. Thromboembolic events after a negative TEE are common and have significant clinical importance. One possibility is that TEE has limited power to detect a preexisting small LA thrombus or sludge. Although dense spontaneous echo contrast was not systematically evaluated in this survey, sludge is not only considered to be a precursor, but may also mask the detection of a well-formed LA thrombus. Baseline myocardial structure such as the pectinate muscles of the LA appendage may also be sometimes erroneously diagnosed as LA thrombus, while the contrary can lead to its underdiagnosis. However, as the CHADS2 score was zero in one of these two patients, a more plausible explanation would be de novo LA thrombus formation as a consequence of ECV itself.

Atrial function is known to remain reduced for ≥3 weeks after ECV, and this may provide a milieu for de novo thrombus formation [21]. Based on repeated TEE in five patients with stroke after negative TEE, Black et al. found new or increased LA spontaneous echo contrast in four patients including one patient with a new LA appendage thrombus [22]. When TEE was carried out within 5–15 min of ECV, Grimm et al. found spontaneous echo contrast developing de novo in 4 of the 20 patients [23]. Furthermore, Fatkin et al. carried out ECV in 15 patients while TEE was in place and found that within 10 s of successful ECV, LA spontaneous echo contrast appeared in five and increased in one, which was associated with a transient atrial dysfunction (stunning) [24]. LA thrombus formation immediately after ECV has also been demonstrated on TEE or intracardiac echo during AF ablation [25], [26]. Therefore, the possibility of ECV causing or unmasking atrial stunning and potentially inactivating thrombogenic factors in the atrial endocardium or blood constituents should not be underestimated. More importantly, the limited power of TEE in predicting later LA thrombus formation should be kept in mind.

4.5 LA thrombus resolution with NOAC use

LA thrombus resolution is another important observation in this survey. Of the six patients in whom LA thrombus was detected in the first TEE and later underwent a second TEE, five experienced thrombus disappearance ≥3 weeks later, and one showed thrombus shrinkage after 9 days of anticoagulant therapy. Although prolonged treatment with Dabi 150 mg b.i.d and increasing the dosage up to 150 mg b.i.d or switching to warfarin appeared to be effective in thrombus resolution in three and two patients, respectively, the number of patients was too small and the protocol was not standardized or randomized to be able to reach a definite cause-effect relationship regarding this observation. Stoddard et al. found that of 21 patients undergoing serial TEE, LA thrombus resolved only in one patient at 3–5 weeks of warfarin therapy, and in the 8 additional patients at 5–17 weeks [27]. An ACUTE study sub-analysis revealed complete thrombus resolution in 26 (76.5%) of 34 patients undergoing a repeat TEE after an average of 31.7 days of warfarin anticoagulation therapy [28]. Therefore, LA thrombus resolution is a common phenomenon that can result from either active or passive effects of any anticoagulant.

The potential thrombolytic effect of Dabi has been previously described [29]-[31]. Warfarin anticoagulation effects may not only be difficult to control at times, but could also exert a transient thrombogenic action in its loading phase [32]. By contrast, Dabi may create a consistent anticoagulation milieu easier and faster while inhibiting thrombin binding to fibrin and fibrin degradation products [33], [34]. LA thrombus resolution has also been reported with rivaroxaban and apixaban [35]-[38]. However, additional prospective and detailed studies are necessary before Dabi or any NOAC is recommended for clot resolution.

4.6 Study limitations

There are several limitations in this study. This retrospective study was carried out without following a consistent protocol for Dabi dosage and therapy duration prior to or after ECV. The possibility of selection bias cannot be excluded as a TEE was performed at the discretion of individual doctors. No protocol was provided for dosage change or type of oral anticoagulants, or for the timing of the second TEE after LA thrombus detection, nor was an assessment available to ascertain Dabi adherence before and after ECV. Individual doctors with potentially variable skills made LA thrombus diagnosis by using TEE.

5 Conclusions

LA thrombus developed in 4% of patients with AF who underwent ECV while receiving Dabi. Older patients with higher CHADS2 score who were receiving a lower Dabi dosage or shorter treatment duration were more likely to develop LA thrombus, which resolved with a prolonged or increased dosage. A higher Dabi dosage may be preferred to a lower dosage if acceptable before ECV, but further prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings. Considering the limitation of ascertaining Dabi therapy adherence, performing a TEE in all patients receiving Dabi before ECV may be recommended.

Institutional Review Board information entered in the system

This multi-center study is a retrospective analysis of data obtained from patient charts reviews in which patients' names were concealed (approved date: November 6, 2012, approval number: 2010–192, Hirosaki University).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Mitamura received honoraria for educational lectures from Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brystol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Pfizer. Dr. Nagai and Dr. Watanabe have no conflict of interest disclosures. Dr. Takatsuki received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and Speakers' Bureau/Honorarium from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Okumura received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and Speakers' Bureau/Honorarium from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Eisai.

Acknowledgments

This survey was conducted with the voluntary support of the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society members.

Appendix A

A.1 List of the institutions participating in the survey

Teine Keijinkai Hospital, Hokkaido University Hospital, National Hospital Organization Obihiro National Hospital, Akita Medical Center, Hiraka General Hospital, Iwate Medical University Hospital, Sendai City Hospital, University of Fukui Hospital, Fukui-ken Saiseikai Hospital, Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital, Nihon University Hospital, St. Luke's International Hospital, Jikei University School of Medicine, Toranomon Hospital, The Cardiovascular Institute, Tokyo Metropolitan Hiroo Hospital, Kawasaki Municipal Tama Hospital, Yokohama City Minato Red Cross Hospital, Yamatoseiwa Hospital, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Fukuyama City Hospital, New Tokyo Hospital, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Kameda General Hospital, Dokkyo Medical University Hospital, Saitama International Medical Center, Gunma University Hospital, Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital, Hamamatsu Medical Center, Okazaki City Hospital, Japan Community Healthcare Organization Chukyo Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital, Konan Kosei Hospital, Gifu Heart Center, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu Prefectural Tajimi Hospital, Mie University Hospital, Shiga University of Medical Science Hospital, Hikone Municipal Hospital, Sakurabashi Watanabe Hospital, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka City University Hospital, Tominaga Hospital, Osaka General Medical Center, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Ishikiriseikikai Hospital, Kyoto Prefectural Medical University Hospital, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Nara Medical University Hospital, Nara Prefecture Western Medical Center, Kobe University Hospital, Hyogo College of Medicine Hospital, Hyogo Brain and Heart Center, Tottori Prefecture Chuo Hospital, Matsue Red Cross Hospital, Sakakibara Heart Institute of Okayama, Aichi Medical University Hospital, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Fukuyama Cardiovascular Hospital, Okayama University Hospital, Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital, Tokushima Red Cross Hospital, Ehime University Hospital, Kyushu Hospital, National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka Sanno Hospital, Fukuoka University Hospital, Saga-ken Medical Centre Koseikan, National Hospital Organization Oita Medical Center, and Tomishiro Chuo Hospital.