Decisions Regarding Pregnancy Termination Due to β-Thalassemia Major: a Mixed-Methods Study in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran

Abstract

In the present study, an embedded design was applied in order to conduct a one-year cross-sectional audit of chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and foetal outcomes affected by β-thalassemia major (β-TM) in a prenatal diagnosis (PND) setting. In addition, we explored the decisions regarding pregnancy termination among women whose pregnancy (or child) was affected by β-TM. In the quantitative phase, the available data in the clients’ medical records were analysed, while the qualitative phase was performed using a grounded theory method. Interviews were performed with nine pregnant women who had decided against pregnancy termination despite positive CVS results, 11 mothers who had admitted their child to the thalassemia ward for blood transfusion, and 19 mothers who had received positive CVS results and had decided against pregnancy termination in the preceding year. Over one year, 18.6 % of women decided against pregnancy termination despite positive CVS results. Two main themes related to decisions against pregnancy termination emerged from the qualitative data: 1) Cognitive factors (questioning the reliability of the tests or doubts about the accuracy of the results, understanding disease recurrence, curability, perceived severity of the disease, and lack of “real-life experiences”); and 2) Sociocultural responsiveness (family opposition, responsibility before God, and self-responsiveness). All of the mentioned factors could intensify fear of abortion in couples due to possible regret, and encourage a decision against pregnancy termination.

Introduction

Thalassemia, a haemoglobin disorder, is among the world's most common monogenic conditions (Ishaq et al. 2012). Although this disorder is reported in all ethnic groups and geographic areas, it is more common in the Mediterranean region, Arabian Peninsula, Turkey, Iran, India, and Southeast Asia (Karimi et al. 2008; Ngim et al. 2013; Rund and Rachmilewitz 2000).

In Iran, β-thalassemia is the most common hereditary disorder, affecting approximately 26,000 patients and three million carriers (Ghotbi and Tsukatani 2005). The prevalence of β-thalassemia alleles in Iran has been estimated at approximately 4–8 % (Rahimi 2013). Currently, the Sistan and Baluchestan province, with 2050 patients, has the highest rate of β-thalassemia major (β-TM) in Iran (Miri-Moghaddam et al. 2012).

β-TM is characterized by a deficiency in both alleles of beta-globin genes, followed by the insufficient and unsustainable production of adult haemoglobin. As this condition cannot be cured, patients require lifelong monthly blood transfusions, combined with daily iron chelation therapy starting at a young age (Karimi et al. 2008). In addition, β-TM can place an emotional and economic burden on the affected families. Ultimately, affected patients are unable to enjoy a long life due to difficulty in adherence to treatment (Ahmed et al. 2006b).

Moreover, therapeutic methods, based on gene therapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of thalassemia, are extremely expensive and difficult to implement for people in low-resource countries. Therefore, preventive programmes (comprised of population screening, prenatal diagnosis of β-TM, and selective termination of pregnancy) should be available to couples at risk of β-TM (Ghotbi and Tsukatani 2005; Ngim et al. 2013).

Studies performed in European countries have shown that the United Kingdom has experienced the lowest level of decline in new cases of β-TM (Angastiniotis et al. 1986; Ahmed et al. 2006b). According to previous studies, this phenomenon is most likely related to restrictions imposed by religious beliefs, influence of relatives, and perception of disease severity among Pakistani immigrants (Ahmed et al. 2006a; Ahmed et al. 2006b; Ahmed et al. 2008; Ahmed et al. 2000).

Additionally, studies in Pakistan and Lebanon have shown that cultural beliefs (e.g., belief in fate) and lack of awareness of genetic risk factors play important roles in one's opposition to abortion (Hussain 2002; Zahed and Bou-Dames 1997). In Malaysia, while age, education, and number of affected children were not identified as significant predictors, 73.4 % of the participants were opposed to abortion due to religious beliefs (Ngim et al. 2013).

Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of knowledge and information on thalassemia screening programmes and other resources, particularly in Muslim communities. However, according to previous studies, the high frequency of β-TM in Iran, particularly in Sistan and Baluchestan province, could be attributed to religious beliefs, hope of an effective treatment, consanguineous marriage, and lack of knowledge about prenatal diagnosis (PND) and screening programs (Karimi et al. 2004; Miri-Moghaddam et al. 2012; Rahimi 2013).

Thalassemia Prevention Programme in Iran

In Iran, laboratory screening tests for β-thalassemia were incorporated in compulsory premarital blood tests in 1996. The initial aim of the program was to identify carrier couples in the hope of discouraging marriage between heterozygotes due to the inaccessibility of PND centres and restrictions on abortion in Iran at that time. In fact, by 1999, there was little acceptance that marriage between carriers should be avoided (Samavat and Modell 2004; Zeinalian et al. 2013).

In 2001, the legislation on abortion was revised to allow selective abortions up to 15 weeks of gestation. In addition, a national DNA laboratory was established to facilitate PND via chorionic villus sampling (CVS). Currently, about 25 PND centres, approved by the Iranian Ministry of Health and Education, are available throughout the country. Prenatal tests for thalassemia diagnosis are also covered by insurance companies. Consequently, at these centres, the tests are cost-free for couples, who are at a major risk of having a child with β-TM. However, couples who are not covered by health insurance are required to pay about 15,840,000 Rials ($458).

Although the establishment of β-TM prevention programme in Iran has led to a 70 % decline in new cases of thalassemia throughout the country (Christianson et al. 2004; Moradi and Ghaderi 2013; Samavat and Modell 2004), Sistan and Baluchestan province, which accounts for 3.4 % of the Iranian population, hosts approximately 25 % of new cases of thalassemia in Iran each year (Hadipour Dehshal et al. 2014; Miri-Moghaddam et al. 2012).

Sistan and Baluchestan province is located in the southeast of Iran, close to the Gulf of Oman on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan. This province is subtropical and malaria is endemic to this region (Rahimi 2013). In fact, the high frequency of β-thalassemia alleles could be related to the high prevalence of malaria. Also, this province has the second largest surface area of all provinces in Iran (180,726 km2).

The large area of Sistan and Baluchestan province has caused difficulties in travelling to the capital city. In addition, referral to PND centres is a costly and time-consuming process, leading to geographical and financial problems for families. Absence of genetic counselling services (e.g., trained board certificate professionals or other trained staff) is also a factor which should not be overlooked. These barriers hinder the process of counselling before CVS. In addition, under such circumstances, no professional support can be provided for the couples after receiving positive CVS results to help them make an informed decision regarding pregnancy termination.

The population of Sistan and Baluchestan province primarily consists of two ethnolinguistic groups (i.e., Baluch and Sistani); the Baluch represent the majority of the population in this province. Baluch people are predominantly Sunni Muslims, while non-Baluch inhabitants are Shiite. According to previous studies, consanguineous marriage is the socioculturally preferred type of marriage among Baluchi people (Miri-Moghaddam et al. 2012; Rahimi 2013). According to official reports, 25 % of women, aged 14–44 years, are illiterate in the province. Additionally, in 2012, the population growth rate and total fertility rate were 2.7 % and 3.77 % for women of reproductive age in Sistan and Baluchestan province, while the national rates were 1.4 % and 2 %, respectively (Moudi et al. 2014).

As presented in a study by Christianson et al. (2004) assessment is a key factor for helping managers develop and keep a service sustained and growing. While a number of studies have been conducted to evaluate the performance and effectiveness of β-TM PND services in Iran, the performance of the PND centre in Sistan and Baluchestan has not been assessed so far. Therefore, in the context of the β-TM prevention programme in Sistan and Baluchestan, this mixed-methods study was designed and conducted to achieve two major objectives: (1) To present a one-year cross-sectional audit of CVS in Sistan and Baluchestan province with the aim of reporting all foetal outcomes affected by β-TM; and (2) To explore the reasons women (with a pregnancy or child affected by β-TM) had for deciding against pregnancy termination.

Methods

Design

An embedded design (with a predominantly qualitative method) was applied to address different research questions in the present study (Creswell et al. 2008). This two-phase mixed-methods research was carried out with the aim of analysing and interpreting the data obtained in the quantitative phase, and using in-depth interviews to understand women's perceptions. Interviews were performed after the participants had agreed to undergo CVS sampling, had received positive CVS results, and had decided against pregnancy termination, despite positive β-TM diagnosis. In fact, findings from this type of mixed-methods study arguably can enrich descriptions of women's behaviours (Creswell et al. 2008).

Participants and Data Collection Procedures

- Phase 1- Decisions regarding abortion following PND

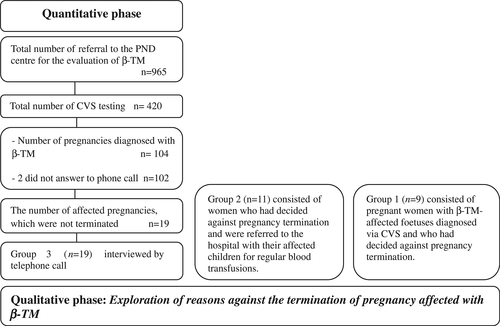

In this phase, statistical analysis was performed on the data, routinely collected in the PND centre. The data used in this study were collected from February 21, 2012 to February 21, 2013. First, a list of all couples, referred to the PND centre for the evaluation of β-TM, was prepared. Second, the number of CVS procedures, as well as the number of foetuses diagnosed with β-TM through CVS sampling, were determined. Third, the lead researcher contacted by phone, mothers who had a prenatal diagnosis of β-TM during pregnancy (n = 104). Two women did not respond to the phone call, and they were consequently eliminated from the analysis, resulting in a sample of 102 women for this analysis Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the design

- Phase 2- Exploration of reasons against the termination of pregnancy affected with β-TM

- Group 1 (n = 9) consisted of pregnant women with β-TM-affected foetuses diagnosed via CVS and who had decided against pregnancy termination. Six women were nulliparous, and three were multiparous. The participants were selected in accordance with the research objectives at the PND centre. The lead researcher was present in the centre, where couples were informed about the β-TM diagnosis for the first time. The purpose of the researcher's attendance was to observe the couples’ and their families’ reactions and to assist with the consultation process.

- Group 2 (n = 11) consisted of women who had decided against pregnancy termination and were referred to the hospital with their affected children for regular blood transfusions.

- Group 3 (n = 19) included women who participated in the initial follow-up phone calls described in Phase 1 above, and who had also declined pregnancy termination in the preceding year.

The sampling process was terminated when the researchers reached data saturation and had a proper understanding of the emerging themes (Bassett 2004; Morse 2007).

The initial contact with the participants was made by staff at the PND centre. After asking Groups 1 and 2 for their oral consent, interviews were carried out in the PND centre and thalassemia ward between February 21, 2012 and October 21, 2013; only one woman preferred to be interviewed in their own house. The purpose of the study was explained to the participants, and they were assured that their participation in the study was completely voluntary. Additionally, the participants were assured about the confidentiality of the data and were allowed to leave the study at any time.

After obtaining the participants’ permission, all interviews were recorded digitally. All interviews were performed in Farsi by the lead researcher and lasted for 1 h on average. The participants were interviewed only once. Of 20 interviews, four nulliparous women were accompanied by their husbands, while others attended the centre with their mothers or other family members. Additionally, the lead researcher made notes after each interview and read the transcripts; this step helped the researcher understand different dimensions of the research questions (Creswell et al. 2008). All interviews were transcribed verbatim (with no need for translation) and analysed.

Instrumentation

A semi-structured interview guide was used to explore the reasons that the women took into account when deciding about pregnancy termination due to β-thalassemia major.

The lead researcher started a conversation with the participants by asking open-ended questions, such as “Please, explain to me how you decided not to terminate your pregnancy.” or “Please, describe the full story.” As women told their stories, special attention was paid to cognitive aspects (e.g., knowledge about β-thalassemia major), and sociocultural issues (e.g., religious beliefs; influence of others…) that arise. To encourage women to talk more and explain issues, further open-ended questions were asked, such as “Why?”, “Explain more”, “Why are your family members opposed to the termination of pregnancy?”, “Give me an example”, and “Tell me more.”

Ethical Approval

Permission was obtained from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran (June 9, 2014, Approval No.: 6439). In addition, permission was obtained from the directors of Ali Asghar Hospital (PND centre and thalassemia ward).

Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were analysed independently. In the quantitative phase, statistical analysis was performed, using SPSS version 16. Two-tailed tests were used to compare the variables between the two groups. Also, Fisher's exact test was performed to analyse categorical and binary data. Continuous variables (age of men and women) were examined in terms of normal distribution, using a Shapiro-Wilk test. In case the data were not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney U test was applied. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In the qualitative phase, the data were analysed according to grounded theory principles, especially methods developed by Strauss and Corbin (Pidgeon and Henwood 2009). The researcher listened to each recording, transcribed it verbatim, and read it several times to gain a deeper insight into the subject matter. The first step included line-by-line reading and open coding, performed by the lead researcher and an anthropologist; they agreed on the codes which corresponded to significant words and sentences.

To validate the emerging themes, two women were given the transcripts and codes from their interviews to confirm that our interpretation was accurate and reflected the reality of their experiences (Limb 2004). Next, through constant comparison, similar concepts were extracted and classified within different categories. The lead researcher and a medical anthropologist worked together to understand the key relationships between categories and link them together in a new format.

Results

Quantitative Results

From February 2012 to February 2013, a total of 965 couples were referred to the PND centre to test for β-TM during pregnancy. Based on the findings, 104 (24.7 %) out of 420 pregnancies, tested by CVS, were diagnosed with β-TM. Two women did not respond to the phone call, and they were consequently eliminated from the analysis, resulting in a sample of 102 women for this analysis. Of these 102 affected pregnancies, 18.6 % of the couples decided against abortion (Table 1). The demographic characteristics of the 102 women whose pregnancy was diagnosed with β-TM are presented in Table 2. In terms of ethnic composition, 83.3 % of these 102 women, who did respond to the phone call, were Baluch and 16.7 % were Fars; also, the majority of them (80.3 %) were Sunni. Eighty-three women (81.4 %) made a decision to undergo an abortion, while 19 women (18.6 %) declined an abortion Statistical analyses indicated no significant demographic difference between these two groups in (e.g., education, age, and history of affected children in the family), with the exception of the partner's educational level. A greater percentage of women who declined abortion had a partner with a lower level of education declined abortion compared to women who decided to undergo an abortion, (57.9 % vs 22.9 %) Table 2.

| Total number of referrals for β-TM testing | Number of CVS tests | Number of Pregnancies diagnosed with major β- thalassemia | Number of affected pregnancies for which abortion was declined | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 965 | 420 | 43.5 | 104 | 24.76 | 19 | 18.6* |

- *Two women did not respond to the phone call, and they were consequently eliminated from the analysis, resulting in a sample of 102 women for this analysis

| Demographic characteristic | Accepted abortion n (%) | Decided against abortion n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 83 (81.4) | n = 19 (18.6) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Baloch | 70 (84.3) | 15 (78.95) | |

| Fars | 13 (15.7) | 4 (21.1) | 0.51 |

| Religious | |||

| Sunnis | 66 (79.5) | 16 (84.2) | |

| Shiites | 17 (20.5) | 3 (15.8) | 0.75 |

| Education levels of women | |||

| Illiterate & elementary | 27 (32.5) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Middle school & higher | 56 (67.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.22 |

| Education levels of partner | |||

| Illiterate& elementary | 19 (22.9) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Middle school & higher | 64 (77.1) | 8 (42.1) | 0.0025 |

| History of affected children | |||

| Yes | 35 (42.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| No | 48 (57.8) | 13 (68.4) | 0.44 |

| Family history | |||

| Yes | 13 (15.7) | 6 (31.6) | |

| No | 70 (84.3) | 13 (68.4) | 0.18 |

| Age of women | |||

| Mean ± SD (years) | 28.07 ± 6.52 | 26.68 ± 6.2 | 0.40 |

| Age of partner | |||

| Mean ± SD (years) | 32.73 ± 9.43 | 31.89 ± 6.77 | 0.96 |

Qualitative Results

“I was tested in the hope of my child's health. I did not expect thalassemia major” (Gravida 1, age: 17 years).

As illustrated, women referred to these centres undergo testing to be assured about the health of their foetus. Such assurance may decrease their anxiety and/or satisfy their sense of curiosity (Table 3).

| Demographic characteristic | n |

|---|---|

| Gravid | |

| First pregnancy | 12 |

| Second pregnancy | 11 |

| Third and more | 16 |

| Children with major β- thalassemia | |

| 0 | 19 |

| 1 | 13 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 and more | 2 |

| Number of prior abortions after CVS | |

| 0 | 33 |

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 and more | 1 |

| Religious affiliation | |

| Sunni | 33 |

| Shiite | 6 |

| Age of women | |

| Mean ± SD (years) | 27.36 (±6.78) |

| Age of partner | |

| Mean ± SD (years) | 32.54(±7.73) |

“Such children should be aborted” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years).

These women expressed that they were not prepared for either the diagnosis or the suggestion that they terminate the pregnancy.

Reasons for Declining Termination

The reasons for the opposition by women, their partners’ and their families to abortion could be divided into two main themes: 1) Cognitive factors (questioning the reliability of the tests or doubts about the accuracy of the results, understanding of disease recurrence, curability, perceived severity of the disease, and lack of “real-life experiences”); and 2) Sociocultural responsiveness (family opposition, responsibility before God, and self-responsiveness).

Theme 1- Cognitive Factors

Reliability of the Tests or Doubts about the Accuracy of the Results

Almost all women discussed the following subject in their interviews: “There is a 1% chance that the baby is healthy. I think the results of sampling and genetic tests might be inaccurate.” (Gravida 2, abortion: 1, age: 25 years).

“(People) said that the experts might be wrong. Who can guess God's plans? My baby might be born healthy.” (Gravida 1, age: 28 years)

“Who knows what's going to happen tomorrow? One of my acquaintances was told that her baby is a girl after sonography, but the baby turned out to be a boy; they had visited the best doctors.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

“There are people who had been recommended to have an abortion, but they declined to do so. Now, they have a healthy child.” (Gravida 1, age: 22 years)

Women had a tendency to be doubtful about the test results when they were not in accordance with their hopes and expectations for the future; therefore, they looked for reasons to question the validity of the test results.

Understanding of Disease Recurrence

“I was told that if the baby is diagnosed with thalassemia major in the first pregnancy, it will not re-occur in the second pregnancy. So, in my second pregnancy, when they told me that the child has the same condition, I doubted the accuracy of the tests.” (Gravida 2, abortion: 1, age: 28 years)

“They confidently said that one out of four children would have thalassemia major.” (Gravida 4, second child affected by β-TM, age: 29 years)

Curability

“[Experts] said that my husband and I both have thalassemia minor and that we should not have children until we have completely used the prescribed medications [i.e., iron and folic acid]. We were told that I could get pregnant after receiving complete treatment.” (Gravida 1, age: 17 years)

A belief that following such preconception advice can prevent the disease, may cause couples to doubt the accuracy of the reported test results, thereby preventing them from making an informed decision about the continuation or termination of pregnancy.

Perceived Severity of the Disease

“We see children with thalassemia (major) going to school; it seems like they have no problems. So, I guess there will be no problems if the child receives blood transfusions once a month.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

The women expressed a desire to be informed about the most important problems threatening the life of their newborn and to be familiarized with the difficulties they may encounter in the long run. These women need to understand that dealing with these long-term problems is not achievable in practice by their families or the healthcare system due to the current realities of the society (i.e., socioeconomic status and level of knowledge).

Lack of “Real-Life Experiences”

“I'd heard that the child would need blood transfusions, but I hadn't seen it with my own eyes. Now, they cannot find her vein sometimes (pointing to a three-month-old girl with β-TM) or her vein is ruptured. I start to cry every time she has a blood transfusion. They cannot understand this, unless they experience it in real life. I would never make such a decision again. If I have an affected pregnancy again, I'll have an abortion.” (Gravida 4, age: 29 years)

“The problem was that I had no experience and had never seen the problems of these children. We did not have any children in our family with thalassemia [major]. Therefore, it was difficult for our families to accept the abortion.” (Gravida 1, age: 28 years)

Theme 2. Sociocultural Responsiveness

Family Opposition

“My sister in law told me I had no right to have an abortion. They called my husband and told him that you have no right to consent to the abortion.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

“Although the parents should make the final decision together, the family should be involved and informed, as well. In fact, satisfying the family is much harder.” (Gravida 2, abortion: 1, age: 28 years)

Some of the causes of family members’ opposition to abortion were as follows: fear of future infertility, social preference for large families in our study region, preference to have a son, being an only child (in one of the parents), parents’ desire to extend the family, lack of experience with the problems of children with β-TM (especially when the couple's parents have thalassemia minor while having no children with β-TM), and religious issues.

“We were worried that our families would get upset with us. They could refuse to live with us, talk to us, or visit us.” (Gravida 1, age: 17 years)

Responsibility before God

“After conception, it is a sin to talk about abortion. In fact, even thinking about it is a sin.” (Gravida 4, second child with β-TM, age: 26 years)

“The person who aborts the baby or is willing to do so is responsible for the murder…The parents who consent to abort their baby kill their child with their own hands.” (Gravida 1, age: 28 years)

“A month after the abortion, my brother in law fell in a well, and my husband's nephew drowned in the sea. I'm so regretful. I ask God to forgive me! I repent! I will not do it again.” (Gravida 3, abortion: 1, age: 31 years)

“God will punish one who commits this sin in the world after death…You will be held accountable on the Day of Resurrection. They will ask you if you have murdered your child; you will go to hell.” (Gravida 1, age: 28 years)

As can be seen in the participants’ statements, despite the permission granted by Moulavi (a famous religious leader) for abortion up to the end of the 18th week of gestation (from the first day of pregnancy, as stated by the centre experts), family members and mullahs sometimes prohibit couples from abortion from the time of embryonic development or when there is evidence of foetal heart beat at the eighth week of gestation.

Self-Responsiveness

“I thought that I could abort the baby, but my conscience would not accept it.” (Gravida 1, age: 18 years)

“I loved my baby. I felt sick and distressed because of him (the baby). This feeling of motherhood discouraged me against abortion.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

“I have compassion for myself and my children. I wonder why I aborted my baby!” (Gravida 3, age: 30 years)

“I have become independent and live in a separate house from my parents. My husband is still young; I wanted to at least feel a sense of parental liability.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

“Do you think it is true that a man may feel sad for an entire year because of thalassemia in our children?” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

“I was told that the baby might have thalassemia major. I prayed for a healthy baby and asked God to work a miracle.” (Gravida 2, age: 27 years)

“Surely, there must be a reason why God has given you a baby with thalassemia major. If God wanted you to have a healthy baby, he would have given you a healthy baby. Why do you want to start a war with God? No one should throw away the gift of God.” (Gravida 1, age: 25 years)

Discussion

The present study showed that 18.6 % of women who had positive CVS results for β-TM decided against pregnancy termination. Such decisions are always accompanied by varying degrees of uncertainty, and couples might be worried about possibly regretting their decision (Reb 2008; Smith 1996). In agreement with previous studies, the gathered data showed that decision-making is a multifaceted process, dependent on the couples’ doubts and fears of sociocultural pressures (Ahmed et al. 2008; Jeon et al. 2012; Karimi et al. 2008; Karimi et al. 2004).

Cognitive Factors

In agreement with previous research, we found that women (and their partners) had misunderstandings and misinterpretations about the risks of β-TM as a genetic disease (Zahed and Bou-Dames 1997; Ahmed et al. 2012). These misunderstandings created doubts regarding the accuracy of CVS testing and lead to misinterpretations about the risk of disease recurrence and accurate diagnosis. Consequently, these doubts can intensity the couple's fear of making the wrong decision, cause delays in the process of decision-making, and promote opposition to pregnancy termination in order to prevent any possible regrets.

The present study identified key aspects which need to be emphasized in this area, including education for couples using a clear description of β-TM inheritance and providing information about the treatment of β-TM and accuracy of prenatal test results. It is also important that the medical staff communicate the information to patients in a culturally sensitive manner so that unintended meanings are not conveyed (Wong et al. 2011a; Wong et al. 2011b).

The Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has provided free access to blood transfusion and iron chelation therapy so that young β-TM patients can live relatively normal lives. The lead researcher in the present study observed the medical staff as they informed the couples about their newborns’ need for monthly blood transfusions. However, they did not talk about the medical or emotional consequences of long-term complications. Therefore, when women realized that their child could have a relatively normal life, they declined to terminate the pregnancy (especially when the infant had the desired sex or was the first child of the family) (Ahmed et al. 2008).

Previous studies (Larrick and Boles 1995) have shown that individuals anticipate regret prior to decision-making and try to avoid options which expose them to disappointment (Connolly and Zeelenberg 2002; Humphrey 2004). In line with previous research (Ahmed et al. 2008; Karimi et al. 2004), the qualitative section of the study highlighted that real-life experience of the disease (observation of children with β-TM) and the perceived severity of the condition (e.g., long-term adverse effects) (Ahmed et al. 2006a; Ngim et al. 2013) could play important roles in the decision to terminate the pregnancy. Generally, providing detailed information about the long-term physical and emotional consequences of β-TM for children allows informed decisions, which may be different from those rooted in misunderstandings and misinterpretations about β-TM (Larrick and Boles 1995; Ahmed et al. 2008; Wong et al. 2011b). These women need to understand that dealing with these long-term problems is not achievable in practice by their families or the healthcare system due to the current realities of the society (i.e., socioeconomic status and level of knowledge).

Sociocultural Factors

According to previous studies by Ahmed et al. (2006a, 2006b), decisions about pregnancy termination are mostly made in a broader sociocultural context (Hussain 2002) in the presence of family members (Lopez et al. 2014). Consequently, relatives with limited health information may also encourage couples to “do nothing” to avoid the anticipated regret due to abortion. This could influence the couple's opinion and final decision and would ultimately affect the family's quality of life.

Furthermore, regret can influence a decision made with uncertainty when the couple compares the outcomes with what they think would have happened if they had made a different decision (Larrick and Boles 1995). Similar to previous studies (Ahmed et al. 2008), some women preferred having a child for a short period of time to having none at all (given the sense of motherhood or make husband more responsible to the family); this type of decision-making helps women avoid short-term regrets. However, as the present study indicated, a decision which seems well justified at the time may appear unjustified later on and lead to long-term disappointment (after having a child with β-TM and experiencing the condition) (Bell 1982; Connolly and Zeelenberg 2002; Reb and Connolly 2009).

Under such circumstances, different strategies are usually implemented to justify the decision in the long run. First, people turn to their religious beliefs to make the negative outcomes more tolerable and to avoid self-blame and potential regret. Second, they may seek information in to justify their decision (e.g., comforting reminders by others) or leave the responsibility of the decision to others (Giorgetta et al. 2013).

Strengths and Limitations

Although this study is the first research to provide in-depth information about women's reasons for opposition to pregnancy termination (despite β-TM diagnosis), the results are limited. The qualitative data were collected from a fairly small group of women (mostly Baluch and Sunni), who were referred to the PND centre in Zahedan, Iran at the time of the study; therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Moreover, qualitative data are not intended to be generalized to the population of interest. Given the sensitive nature of this study, it is possible that some interviewees were not forthcoming in their responses. Despite these limitations, the results of the present study could offer a valuable insight into the decisions regarding abortion in this group of women, which may be beneficial to local managers and policymakers.

Research Recommendations

Future studies are needed to determine to what extent the fear of regret is involved in the decision to terminate a pregnancy due to β-TM diagnosis. Additionally, it would be interesting to conduct long-term studies on couples who decide to maintain or terminate their pregnancy to study their experience of regret (both anticipated regret and actual regret).

Practical Implications

The findings of the present study showed that counsellors should place more emphasis on women's or couple's cognitive and sociocultural concerns and offer them space and time so that they can process their doubts and emotional distress. Additionally, the findings of the present study could help counsellors in PND centres to determine which subjects to discuss with women/couples so that they can make a decision that minimizes subsequent regrets.

In accordance with the study by Wong et al. (2011a), the present findings revealed the social aspects of pregnancy. Consultation around communication skills, combined with an in-depth understanding of the context of decision-making, could promote logical decision-making regarding pregnancy termination, allowing couples to better justify their decisions and reduce potential regret.

Conclusion

In Iran, laboratories have been equipped to screen the referred cases of thalassemia. Consequently, patient registration and prenatal diagnosis have sharply increased. While such genetic screening networks appear to be a prerequisite for decreasing the number of new cases of β-TM, there are several pitfalls in special contexts, such as Sistan and Baluchestan province. First, there is a major need for healthcare professionals (consultants) to provide communication skill training for the couples. Second, the feeling of regret is a crucial factor in avoiding abortion, despite β-TM diagnosis. The consultant should know that couples make their decisions within a changing sociocultural context, based on their moral values, beliefs, and preferences (Ahmed et al. 2006a).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants and the staff who contributed to the present study. Additionally, we would like to thank Zahedan University of Medical Science (ZAUMS) for the financial support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests in this study.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institution and natinal) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.