Sex Education and Intellectual Disability: Practices and Insight from Pediatric Genetic Counselors

Supplemental material for this article is available upon request.

Abstract

Intellectual disability (ID) with or without other anomalies is a common referral for genetic counseling. Sessions may include discussions of reproductive implications and other issues related to sex education. Patients with ID regularly meet barriers when trying to obtain sex education due to the misperceptions of others as being either asexual or that such education would promote inappropriate sexual behavior. In this pilot study, we surveyed genetic counselors to explore their experiences with being asked to provide sex education counseling and their comfort in doing so for patients with ID ages 9–17. Results were analyzed from 38 respondents. Caregivers and patients most frequently requested information on puberty, sex abuse prevention, and reproductive health. Genetic counselors were most comfortable when they could provide sex education counseling within the context of a particular condition or constellation of features. They were least comfortable when they lacked familiarity with the patient, caregiver, or the family's culture. The most frequently cited barriers that prevented genetic counselors from providing sex education counseling were lack of time, lack of training, the patient's ID being too profound, and a belief that genetic counselors should not be responsible for providing sex education counseling. While many respondents reported that providing sex education counseling is not considered within the scope of a genetic counselor's practice, they also noted that patients’ families initiate discussions for which counselors should be prepared. Respondents indicated that resource guides specifically designed for use by genetic counselors would be beneficial to their practice. Genetic counselors have the opportunity to embrace the role of advocate and broach the issue of sexual health with caregivers and patients by directing them toward educational resources, if not providing sex education directly to effectively serve the needs of patients and caregivers.

Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID) is described by the American Psychiatric Association as decreased adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains that occurs prior to 18 years of age, (APA 2013); it has a prevalence of 1–3 % within the general population (Shevell et al. 2003). The diagnosis of ID is made through a combination of standardized intelligence testing and clinical assessment of adaptive functional skills, which include self-care, self-direction, and interpersonal skills. ID is considered to be an IQ score of approximately two standard deviations below the mean, or a score of 70 or below (Schalock et al. 2010). ID is classified as mild, moderate, severe, and profound. Individuals diagnosed with mild ID account for 85 % of the population with ID (King et al. 2009). Persons with mild ID are able to be educated up to a 6th-grade level, are usually capable of maintaining a steady job, and can live in the community with minimal supervision while those with profound ID can achieve education lower than 1st-grade and are unable to consistently perform daily activities with independence (Morano 2001).

Causes of ID include but are not limited to genetic abnormalities, infection, trauma, complications of prematurity, and various environmental and chemical exposures. Genetic abnormalities are causative for 17.4–47.1 % of ID (Moeschler and Shevell 2006). Trisomy 21 is the most common chromosomal abnormality, and full mutations of the FMR1 gene, or Fragile X syndrome, is the most common single gene disorder which cause ID (Rauch et al. 2006). As such, ID with or without other anomalies is a common referral in the genetic counseling field. Genetic counselors often meet with patients and families to discuss, among other topics, the cause of ID and associated recurrence risks for a particular condition. The discussion of reproductive implications therefore opens the potential for discussions regarding sex education.

Sex education empowers individuals with ID to enjoy and pursue personal sexual fulfillment and to protect themselves from abuse, unplanned pregnancies, and sexually transmitted diseases (Gürol et al. 2014). Individuals with ID typically access information on sexuality through the following sources: school or community programs, parents or caretakers, peers, or the media (Neufeld et al. 2002). It is important for individuals with ID to have access to developmentally appropriate and accurate sex education information and reference materials in order to develop a proper understanding of sexual concepts. Counseling on sexual issues is crucial for the successful education of patients with ID as they are capable of pursuing sexual relationships (Koetting et al. 2012).

The majority of individuals with ID will develop secondary sexual characteristics, but the onset of puberty varies widely (Morano 2001). Adolescents with ID have reproductive ability, sexual interests, and sexual activity that are identical to the range observed in the general population (Johnson and Johnson 1982). Despite the development of secondary sexual characteristics and interest in sexual activity, the concept of educating individuals with ID about sexual health can be controversial.

People with disabilities are often incorrectly deemed as childlike, asexual, or in need of protection (Murphy and Elias 2006). On the other end of the spectrum, they may be viewed as inappropriately sexual or as having uncontrollable urges (Neufeld et al. 2002). Such perceptions of unaffected individuals can limit access to sex education for individuals with ID (McCabe 1993) as some believe that providing sex education to individuals with ID would then encourage deviant sexual behavior rather than promote health and wellbeing (Pownall et al. 2012). The result is limited sexual knowledge, lack of relevant sexual health education, and restricted social and sexual opportunities for individuals with ID (Thompson et al. 2014).

Levy and Packman (2004) described genetic counselors’ practices in exploring issues of sexual abuse prevention with pediatric patients with ID. They found that a majority of responding genetic counselors acknowledged that sex education and sexual abuse prevention are important and relevant for their patients. While the study provided age appropriate recommendations for genetic counselors to introduce sex education and abuse prevention into their sessions, there was no report on the practices of genetic counselors in providing sex education counseling to pediatric and adolescent patients with ID.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this pilot study was to determine if genetic counselors were being asked to provide sex education counseling on a variety of topics to patients with ID ages 9–17 and what barriers prevented them from doing so. The study also addressed genetic counselors’ comfort level with providing sex education counseling in certain contexts and also gauged their interest in obtaining suitable resources and training.

Methods

The Brandeis University Institutional Review Board approved the research study.

Recruitment

Recruitment notifications were sent via email to all members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). Notification occurred through the NSGC's email blast service to approximately 2900 members in order to recruit individuals with current or prior experience in a pediatric clinic. The NSGC 2014 Professional Status Survey indicated approximately 232 currently practicing pediatric genetic counselors. An initial notification email included a description of the study, participation requirements, and a link to the survey. The online survey was anonymous and was made available through Qualtrics survey software for 2 weeks.

In order to be eligible for participation in the survey, the genetic counselor respondents had to have current or past experience counseling pediatric patients (ages 9–17 years) in a clinical setting outside of an internship encounter. The survey required participants to read and write in English. Respondents were offered the opportunity to enter a random drawing for one of three $50 Amazon.com gift cards.

Instrumentation

We developed an instrument consisting of 25 questions that included multiple choice, Likert scale and open-ended response formats. It was designed to capture the following domains of information: 1) respondent demographics and background; 2) history of requests for sex education-oriented counseling from patients with ID and their caregivers; 3) comfort with providing sex education-oriented counseling to patients with ID and their caregivers; 4) perceived barriers to providing sex education-oriented counseling to patients with ID and their caregivers; 5) respondent interest in additional sex education training and resource identification. Survey respondents were asked to complete the same set of history, comfort and perceived barrier questions regarding counseling for two different age groups (9–12 and 13–17) of children diagnosed with ID in order to account for the likely response variance based on developmental stage.

The survey section measuring the history of requests for sex education-oriented counseling provided a list of sex education topics that genetic counselors may have been asked to address including: abstinence, contraception and condoms, developmentally appropriate sexual behavior, puberty, reproductive anatomy, reproductive health, reproductive rights, and sex abuse prevention.

We designed 14 hypothetical clinical scenarios to allow respondents to critically assess their comfort levels in providing sex education counseling based upon: their relationship with the patient (establishment of rapport); awareness of the patient's sexual activity status and/or relationship status; patient gender; genetic condition; patient pregnancy risk/fertility status; the presence of a physical disability; respondent familiarity with the patient's culture; and the severity of the patient's ID. Each clinical scenario is listed in Table 2.

Data Analysis

Data analysis included frequencies, descriptive statistics, and correlation analyses using SPSS software version 22. The open-ended responses were read and organized around common themes. Because of the small number of surveys and relatively brief response lengths, the use of specialized qualitative software was unnecessary.

We asked respondents about the most commonly requested areas of sex education that professionals are called upon to address. For each of these areas, we asked respondents to indicate how often they have been asked to provide information during their sessions with patients with ID ages 9–12 and also ages 13–17. Responses included ‘Never’, ‘A few times’, ‘Sometimes’, ‘Frequently’, and ‘Always’. Due to the nature of similarity of ‘A few times’ and ‘Sometimes’, the two categories were merged into one for data analysis and renamed as ‘Sometimes’.

The research team conducted independent sample t-tests and correlation analyses in order to determine if respondent demographics (age, years of experience in counseling patients with ID ages 9–17, type of clinic, and region) affected the counselors’ responses within each of the survey domains.

Results

Thirty-eight surveys were completed and analyzed. There was a conservative estimated response rate of 13.4 % (31/232), as 7/38 indicated they were no longer practicing with the designated patient population. Three were missing responses for one section of the survey but were retained in the data analysis. Response rates fewer than 38 are noted when indicated. Fourteen respondents provided information to the three open-ended questions included in the survey. Open-ended responses are noted with quotation marks and italicized text below.

Demographics and Background Information

The majority of respondents were female, Caucasian, and worked in a hospital setting (Table 1). The distribution of respondents represented all six regions as designated by the NSGC, with the majority of respondents (34.2 %) from Region 4 (AR, IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, OK, SD, WI, Ontario).

| Gender | |

| Female | 37 |

| Male | 1 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 35 |

| Latino | 1 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 |

| Asian | 3 |

| Practice Setting | |

| Hospital | 36 |

| Laboratory | 1 |

| Private practice | 1 |

| Type of clinic | |

| General | 22 |

| Specialty | 16 |

The year of graduation from a genetic counseling program ranged from 1981 to 2014, with the majority of respondents graduating within the last 4 years (mode = 2012). Thirty-seven respondents indicated their ages, which ranged from 25 to 59 (mean 33.95, SD = 8.81).

The total number of years respondents counseled patients with ID ages 9–17 in a clinical setting ranged from 0 (less than 1 year) to 30 years (mean = 7.68, SD = 8.52).

Regarding Being Asked to Provide Sex Education Counseling

Respondents indicated how often parents, caregivers, or patients asked them to provide information on commonly requested areas of sex education for each of two age groups: 9–12 and 13–17, in order to identify if topics were more likely to be addressed based upon the patient's age.

9–12 Age Group

“When the primary caregiver was someone other than a parent, I received more requests for contraception discussions. I did counsel several families about their child's reproductive rights but [n]ot with their child present.”

“Questions have mostly been asked by the parents and not the patients themselves. The parents have asked children to leave the room to discuss these issues without their child present.”

“I think this is just a subject that many patients and their caregivers have varying levels of comfort with. The caregiver may also have strong feelings about whether you discuss this directly with their child or not - I find it is less likely that the ca[r]egiver will want you to discuss this directly with the child in this age range than when the child is older.”

13–17 Age Group

“This group typically appears much more likely to bring up the topic themselves, it seems to me caregivers often defer to GC/MD in this case to discuss information and reinforce safe/developmentally appropriate practices. This is the age group where we ar[e] often telling caregivers (especially parents) that female contraception (pill, ring, shot) is not only okay but safe and appropriate in many circumstances.”

“I think it is much more likely in this age range (especially closer to 17) that the family will be comfortable with the conversation involving the child.”

Regarding Professionals who Should be Prepared to Provide Sex Education Counseling

“… I don't think it's practical for GCs to go into depth about this issue. I DO think GCs should have a basic understanding of the issue and refer when appropriate.”

“I provide information about sex education far more than I ever anticipated going into my position as the genetic counselor for a specialty clinic.”

“I think in pediatric clinics we have a responsibility to provide information on a variety of topics not just genetics. There is no way to be sure that other providers are having this discussion so we should be prepared to.”

Comfort with Providing Sex Education Counseling

Respondents were asked about their comfort in providing sex education counseling in 14 specific scenarios. We asked the same set of questions for the two age groups: 9–12 and 13–17 (Table 2). Respondents’ comfort or discomfort with specific scenarios did not differ significantly as a function of patient age.

| Patients with ID ages 9–12 | Patients with ID ages 13–17 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | Comfortable | Uncomfortable | Very uncomfortable | Would to another health professional | Very comfortable | Comfortable | Uncomfortable | Very Uncomfortable | Would refer to another professional | |

| Have never met the patient/caregiver | 6 (15.8 %) | 11 (28.9 %) | 10 (26.3 %) | 7 (18.4 %) | 4 (10.5 %) | 7 (19.4 %)** | 10 (27.8 %)** | 9 (25.0 %)** | 6 (16.7 %)** | 4 (11.1 %)** |

| Have established rapport with the patient/caregiver | 13 (34.2 %) | 19 (50.0 %) | 4 (10.5 %) | 2 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 13 (37.1 %)1 | 18 (51.4 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| Aware the patients is involved in a romantic relationship | 12 (31.6 %) | 20 (52.6 %) | 4 (10.5 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 16 (45.7 %)1 | 12 (34.3 %)1 | 4 (11.4 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 |

| Unaware if the patient is sexually active | 8 (21.1 %) | 18 (47.4 %) | 10 (26.3 %) | 2 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 9 (25.7 %)1 | 18 (51.4 %)1 | 6 (17.1 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient is female | 13 (34.2 %) | 23 (60.5 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 15 (42.9 %)1 | 17 (48.6 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient is male | 7 (18.4 %) | 20 (52.6 %) | 8 (21.1 %) | 2 (5.3 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 8 (22.9 %)1 | 19 (54.3 %)1 | 4 (11.4 %)1 | 4 (11.4 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient is female and has the potential to become pregnant, which could have reproductive implications | 16 (42.1 %) | 21 (55.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 18 (51.4 %)1 | 16 (45.7 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient has reproductive potential | 13 (34.2 %) | 20 (52.6 %) | 4 (10.5 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 16 (47.1 %)a | 16 (47.1 %)a | 2 (5.9 %)a | 0 (0 %)a | 0 (0 %)a |

| The patient is infertile | 7 (18.4 %) | 23 (60.5 %) | 7 (18.4) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 11 (31.4 %)1 | 18 (51.4 %)1 | 5 (14.3 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient has a physical disability | 6 (15.8 %) | 25 (65.8 %) | 6 (15.8 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 9 (25.7 %) | 19 (54.3 %)1 | 5 (14.3 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| Familiar with the patient's culture | 11 (29.7 %)* | 21 (56.8 %)* | 4 (10.8 %)* | 1 (2.7 %)* | 0 (0 %)* | 11 (31.4 %)1 | 20 (57.1 %)1 | 3 (8.6 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| Unfamiliar with the patient's culture | 1 (2.6 %) | 15 (39.5 %) | 18 (47.4 %) | 3 (7.9 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 3 (8.6 %)1 | 13 (37.1 %)1 | 16 (45.7 %)1 | 2 (5.7 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 |

| The patient's ID is mild to moderate | 10 (26.3 %) | 23 (60.5 %) | 3 (7.9 %) | 2 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 11 (31.4 %)1 | 19 (54.3 %)1 | 4 (11. 4 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

| The patient's ID is severe to profound | 7 (19.4 %)** | 16 (44.4 %)** | 12 (33.3 %)** | 1 (2.8 %)** | 0 (0 %)** | 5 (14.3 %)1 | 18 (51.4 %)1 | 11 (31.4 %)1 | 1 (2.9 %)1 | 0 (0 %)1 |

- *Calculated from 37 responses, **calculated from 36 responses, 1calculated from 35 responses, acalculated from 34 responses

“I only feel comfortable doing so in the context of genetic issues.”

“Had one particular patient with extremely inappropriate behavior, which has been an ongoing discussion with parents. Specialty clinic setting is helpful, since most patients and families who attend are well known to me and the MDs.”

Perceived Barriers to Providing Sex Education Counseling

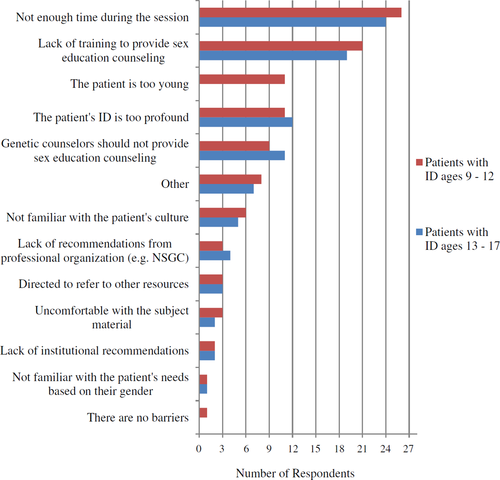

For both the 9–12 and 13–17 age groups, the most frequently noted barriers included: 1) not having enough time during a patient encounter to provide sex education counseling; 2) a lack of training on how to provide sex education counseling; 3) the patient's ID is too profound; and 4) that genetic counselors should not be responsible for providing sex education counseling (Table 3). One barrier that was noted for the 9–12 age group and not for the 13–17 age group was that the patient was perceived to be too young. One respondent elaborated on the role of genetic counselors and lack of time in providing sex education counseling:

“I do not think this is an appropriate role for genetic counselors--this is not what we are trained to do. Our clinic time is so limited, we really need to focus on providing the services that we are uniquely trained to provide.”

“One anecdote- a family declined birth control for their daughter because they felt that they wouldn't know if she had been sexually abused unless she became pregnant/got an STD. This was an interesting conversation, and I really wasn't sure how to discuss those concerns with the family.”

A theme identified from five respondents was that they did not want to assume the caregiver or patients were interested in sex education. We did not specifically offer this as an option as a perceived barrier in the questionnaire.

We conducted Chi-square tests using the dichotomous yes/no responses to each barrier as the independent variable and the ages and years of experience of the respondents as the dependent variables. There were no significant differences in the responses to barrier questions based on the counselor's age or years of experience.

Interest in Additional Sex Education Training and Resource Identification

“I think some training on how to address [sex education] could be helpful, but it is not our area of expertise or our main scope of practice. I think making the recommendation to follow up with the pediatrician or other providers is likely most appropriate in the majority of situations, however it is bound to come up in some sessions and GCs should be prepared for that.”

For all of the survey questions, there were no statistically significant differences in responses based upon the counselor's age, years of experience, type of clinic, or region.

Discussion

Our pilot study was designed to determine if genetic counselors were being asked to provide sex education counseling during their sessions with patients with ID ages 9–17 and how comfortable they were in providing such counseling. Thirty-eight genetic counselor respondents reported that they are being asked to provide sex education counseling on a variety of topics in their sessions with pediatric and adolescent patients with ID. Responses indicated that their comfort in providing sex education is dependent upon external factors such as the level of the patient's ID and counselor's knowledge of the patient's culture.

Questions about puberty, reproductive health, and sex abuse prevention were most frequently posed to genetic counselors regardless of the patient's age. Puberty is understandably more likely to arise in the framework of genetic counseling sessions as a question of if or when puberty will occur as it relates to a particular condition since age of onset and fertility may be affected (Pueschel and Scola 1988; Murphy and Elias 2006). Reproductive health is often addressed regarding a patient's fertility or to identify forms of appropriate contraception. Contraception options may be limited due to patient's dexterity, ability to remember when contraception is needed, or by other medications as a hormonal birth control's efficacy could be impacted by certain drugs (Greenwood and Wilkinson 2013; Smith et al. 1995). Sex abuse prevention is often a concern of parents and primary caregivers (Pownall et al. 2012; Pueschel and Scola 1988). Adolescents with ID are about 5.5 times more likely to be sexually abused than the general population (Verdugo et al. 1995) and creating awareness by providing information to individuals with ID and their caregivers is a critical step in increasing patient knowledge and autonomy in understanding appropriate and inappropriate relationships (McEachern 2012).

Counselors in the present study reported being most comfortable providing sex education when they could do so in the context of a genetic condition. Our scenario described maternal PKU, in which the developing fetal brain and heart are acutely susceptible to high concentrations of phenylalanine when the mother has a poorly controlled diet. Women with PKU may or may not have an intellectual disability based upon their adherence to a low phenylalanine diet. The scenario allowed for a logical progression from genetic condition to discussion of reproductive health, contraception, and other sex education topics. Genetic counselors may want to consider using recurrence risks to segue into gauging patients’ and caregivers’ interest in sex education counseling if they are otherwise concerned about how to broach discussions. One respondent offered their experience: “While I agree that sex ed is not, strictly, a genetic counseling issue, we ultimately need to do what is best for our patient and that includes sex ed. Discussion of recurrence risk is often a great lead-in to a discussion about sex ed, when needed, so genetic counselors are well poised to do this.”

Open-ended responses illustrated that counselors did not want to assume that the caregiver or patient is interested in sex education. Such assumptions could be the result of a lack of rapport or understanding of the patient or caregiver's cultural practices. Our study identified that respondents were least comfortable when they had not established rapport with the patient or caregiver and when they were unfamiliar with their culture. Caregivers and patients may be reluctant to address issues regarding sexuality and sexual health during genetic counseling sessions because they are not provided the opportunity. Even though it may be uncomfortable for genetic counselors to raise the topic of sex education, especially if they are unfamiliar with the caregiver or the caregiver's culture; they may consider doing so as families may not realize they can raise questions about sexuality if the counselor does not bring it up. For instance: “I think often caregivers (especially parents) are hesitant to ask/raise the topic so we often raise the topic for them without being asked and then provide further information based on the level of interest and functioning of the patient/caregiver.”

While respondents acknowledged that they were comfortable with providing sex education counseling in specific scenarios, we identified specific barriers which prevented genetic counselors from doing so. Barriers for both age groups included lack of time during genetic counseling sessions, lack of training, the patient's level of ID is too profound, and the thought that genetic counselors should not be responsible for providing sex education counseling. The barriers we identified are consistent with a prior study of other medical professionals. That study cited time constraints, lack of appropriate training/skills/knowledge base, and the belief that patients were either not sexually active or not interested in sex education as barriers to providing sex education counseling to patients with ID (Schaafsma et al. 2014).

Our open-ended responses demonstrated that counselors understood individuals with ID are sexually active and would have interest in sex education. However, responses revealed a dichotomy between counselors feeling as though they should be prepared for providing sex education counseling but that it is not within their scope of practice. Genetic counselors, while not likely to offer thorough and repeated sex education services directly, can address the need for accurate sexual health knowledge within the context of other genetic counseling services provided (Levy and Packman 2004). Genetic counselors can assess individual sex education needs for patients with ID and provide suitable resources and referrals to those competent in sex education instruction.

The only policy statement of the NSGC in regard to disability states: “It is the goal of the genetic counseling profession to advocate for all individuals and families according to their unique physical, medical, cultural, educational, and psychosocial needs. The NSGC believes that no person should be discriminated against because he or she has a disability” (National Society of Genetic Counselors 2011). Because sexual health can be part of a patient's physical, medical, educational, and psychosocial needs, genetic counselors should be prepared to address multiple aspects of sex education with patients and their families. If counselors are not comfortable with providing sexual health education, they may want to consider utilizing suitable resources and reference material for patients and families.

Respondents expressed an interest in obtaining online and print resource guides to aid in either providing sex education themselves or referring caregivers and patients to appropriate reference material and local sex education professionals. The interest in resource identification was consistent with respondents acknowledging that a lack of training was a key barrier to providing sex education counseling.

Genetic counselors can find reasonable recommendations for initiating age appropriate discussions of sex education and abuse prevention as proposed by Levy and Packman (2004). The following websites provide sex education material designed for those with ID and are grouped by specific diagnoses and various sex education topics: http://www.parentcenterhub.org/repository/sexed/ is available from the Center for Parent Information and Resources and http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/com-health/prevention/hrhs-sexuality-and-disability-resource-guide.pdf was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services.

In addition, the NSGC could create learning modules or lectures on sex education as part of standard of care. Presently, the NSGC provides access to the Cultural Competence Toolkit where one module focuses on an adult female with mild ID who is pregnant. The Cultural Competence Toolkit module could be expanded to include additional scenarios where the patient is a younger age, male, and include patients with moderate, severe, and profound ID to provide a more diverse learning experience for genetic counselors.

Study Limitations

Because of the small sample size, this study's results cannot be considered representative of the experiences of all genetic counselors who have worked in a pediatric setting or the profession as a whole. There are several possible explanations for the low response rate. The survey was launched during a period when the NSGC membership receives numerous invitations to participate in student surveys. The topic itself, or the language used to recruit for the study may have failed to attract respondents. For example, the term “sex education” may have conjured up more formal educational interventions in the minds of potential respondents when, in fact, the scope of our inquiry was more expansive. There also were indications that the structure of the survey was not clear to some participants. One respondent wrote in response to an open-ended question for the 13–17 age group, “Sorry, I didn't realize you were asking about different age ranges.” It is possible that some respondents did not finish the survey because of the confusing structure. Finally, we were not able to address parent/caregiver gender as a variable in this study.

Research Recommendations

We believe that with further refinement of the survey instrument, an expanded qualitative component, and more vigorous recruitment, this study could be replicated with a larger sample of genetic counselors serving individuals with ID and their families. As we note in the Study Limitations section we suggest replacing the term “sex education” and consider less specific terms like “sexual health” or “sexuality”. Additionally, future studies could investigate which sex education resources and referrals are most beneficial to genetic counselors to aid in developing a standard of care or professional recommendations.

Conclusions

Our study findings suggest that patients and families are bringing topics of sexual health forward during genetic counseling sessions. While the nature of the genetic counselor's role might not readily lend itself to providing comprehensive sexuality education to patients, genetic counselors do have a role to play in responding to the needs of patients with ID and their families in this area. Genetic counselors and medical professionals of all disciplines have the opportunity to embrace the role of advocate by broaching issues of sexual health with the caregiver and patient and recommending educational resources, if not providing sex education directly. Because sexuality remains such a sensitive topic for many patients with ID and their families, it is important to be as responsive as possible “in the moment” since there may not be the appropriate follow through with referrals. It is both practical and compassionate for the pediatric genetic counseling profession to act proactively rather than reactively around educating patients and their families on various issues of sexual health.

Acknowledgments

This study was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Genetic Counseling through the Brandeis University Program in Genetic Counseling. The Brandeis University Program in Genetic Counseling and the Brandeis University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences provided financial support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal Studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article