Right hepatectomy with resection of caudate lobe and extrahepatic bile duct for hilar cholangiocarcinoma

Abstract

En-bloc liver resection with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1) is the standard procedure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Although its surgical mortality has been reduced below 5%, it is still a potentially hazardous operation. Complete tumor resection with negative surgical margins and safe reconstruction of bilio-enteric continuity are two principles of the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgeons must pay attention to the variation of the hilar structures including portal veins, hepatic arteries, and bile ducts. Three-dimensional imaging is beneficial not only for understanding anatomical variations but also for preoperative simulations. Since the U-point can be identified by both preoperative imaging and intraoperative inspection, it can be used as the landmark for the hepatectomy and the dissection point of the hilar plate. The hanging maneuver might be useful for both hepatic parenchymal dissection and bile duct dissection just right of the U-point. For safe biliary reconstruction, stay sutures in the anterior wall and transanastomotic stents may be helpful.

Introduction

Resection of the hemiliver with extrahepatic bile duct is the standard procedure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma [1-3]. Since the caudate lobe is located just behind the hilar plate 4 and the caudate branches of the bile duct ramify from the hilar bile ducts, it should be resected together with the hemiliver.

Although its surgical mortality has been reduced below 5% [5-7], caudate lobectomy is still a potentially hazardous operation. In Japan, this procedure is also specified as one of the ‘Highly Advanced Surgery for Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Field’, so the Board-certified HBP surgeon must master it.

Complete tumor resection with negative surgical margins and safe reconstruction of bilio-enteric continuity are two principles of the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Although there are comprehensive textbooks in this field 8, there are additional points to be noted. This manuscript is mainly focused on the operative procedures of right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1) for HBP surgical fellows.

Indications

Patients with tumors mainly located on the common hepatic duct or the right hepatic duct with extension to the left hepatic duct, i.e. Bismuth type II and IIIa 9, are suitable for right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1). If the tumor extends over the second-order biliary radicles, i.e. Bismuth IV, right trisectionectomy is indicated to achieve margin-negative operation. Patients with tumors located on the upper bile duct, i.e. Bismuth type I, with invasion to the right hepatic artery sometimes require right hemihepatectomy to achieve complete tumor clearance.

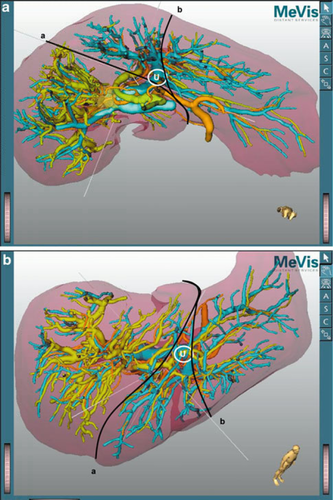

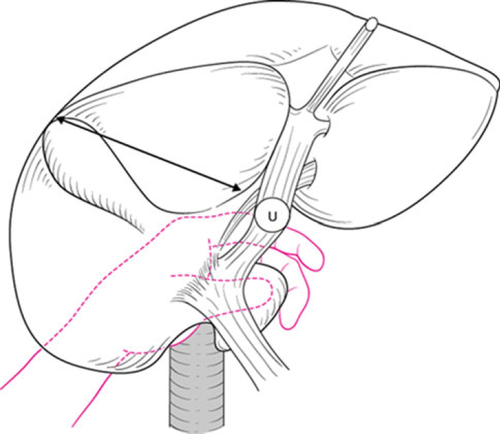

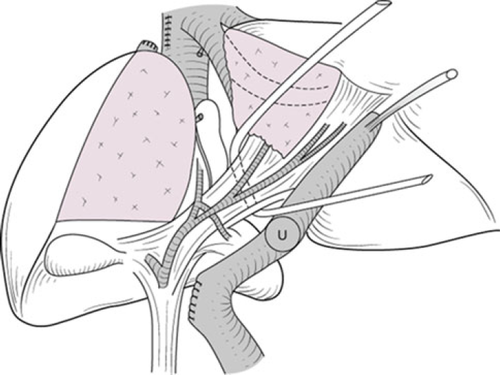

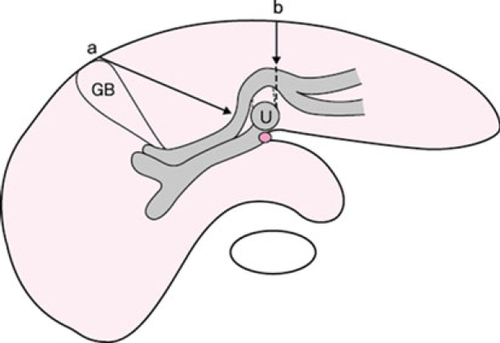

Preoperative three-dimensional (3D) images give valuable information to the surgeon simulating the planned hepatic and vascular resection 10. In right hemihepatectomy or trisectionectomy, the U-point and the middle hepatic vein are the landmarks for hepatic parenchymal dissection (Fig. 1). In right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1), hepatic parenchymal dissection is started from the Cantlie line just toward the right side of the middle hepatic vein. Once the main trunk of the middle hepatic vein is identified, the dissection line is slightly bent to the right side of the U-point. After exposure of the left hilar plate, it can be cut just to the right side of the U-point. Thus, the planned procedure can be achieved in a very similar manner to the preoperative simulation.

In most of the patients who require right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1), the resection rate of the liver parenchyma exceeds 60% of the whole liver volume. Preoperative portal vein embolization is preferable in such patients 11.

Basic surgical procedures

For safety, all procedures should be performed carefully and gently. Vessels should not be grasped directly. Connected tissues such as neural fibers adhering around the vessels must be grasped instead of directly pinching the vessels. Double ligation with a suture ligature is strongly recommended for dissection of the hepatic arteries. Careless traction on the vessel tapes may cause intimal dissection, especially in elderly or diabetic patients. In case of bleeding, the surgeon should gently press the bleeding point with the fingers. Then, dissect around the vessel to obtain a wide operative field. Bleeding from the small portal branch to the caudate lobe can be reduced by temporary clamping of the portal trunk. Loops may help safe and secure dissection and reconstruction of fine vessels.

Sequential procedures of right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy

Laparotomy

The abdomen is entered through a limited midline incision. Careful exploration of the abdomen to search for extrahepatic disease, such as peritoneal dissemination and liver metastasis, is performed. If there is no obvious unresectable factor, the midline incision is extended up to the xiphoid process. A right horizontal incision down to the middle axillary line is then added. Intraoperative ultrasonography may help to observe the relationship between the tumor and the portal vein. In patients with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, the catheter tract should be ablated using pure ethanol to prevent implantation recurrence.

Skeletonization of the hepatoduodenal ligament

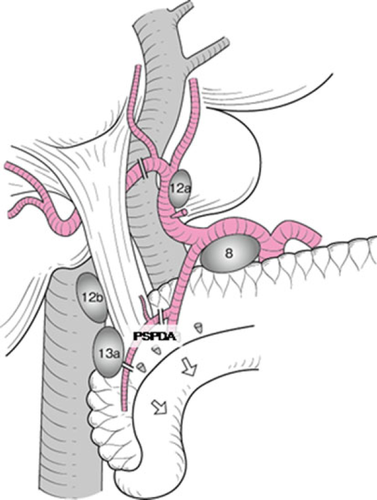

A Kocher maneuver is performed to obtain an entire view of the extrahepatic bile duct. The retropancreatic lymph nodes are dissected (Fig. 2). The common bile duct should be transected above the pancreas. When the posterior superior pancreatoduodenal artery is adherent to the common bile duct, it should be dissected with the bile duct. In patients with endoscopic biliary drainage, these stents should be removed. A 6Fr plastic tube is inserted from the cut end of the common bile duct to avoid biliary stasis during surgery (Fig. 3). Ductal margin should be submitted to frozen section analysis. The cut end of the lower bile duct is then closed by suture ligature.

The common bile duct is turned upward together with associated connective tissue and lymph nodes. The portal trunk and the proper hepatic artery should be isolated and taped. The right gastric artery and the right hepatic artery are divided. When the middle hepatic artery runs close to the left hepatic duct, it can be cut to secure a free margin from the tumor. In such instances, we confirm arterial flow in the medial segment after test clamping of the middle hepatic artery with a small Bulldog clamp. Since most patients have received preoperative portal embolization, a demarcation line emerges on the liver surface.

Portal vein dissection

The entire extrahepatic bile duct is elevated together with associated portal connective tissue. The portal bifurcation can be observed anteriorly. Several small branches to the caudate lobe and the quadrate lobe are carefully ligated and divided. The caudal side of the ligamentum venosum is also ligated and divided. At that time, the surgeon should distinguish the left hepatic artery from the ligamentum venosum.

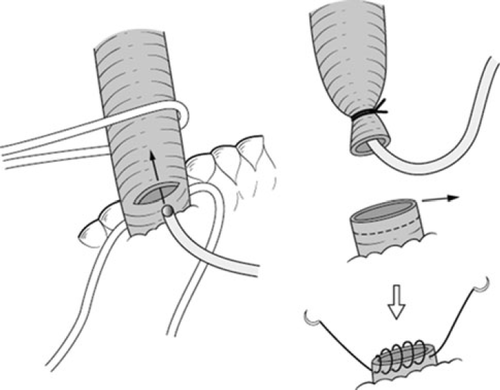

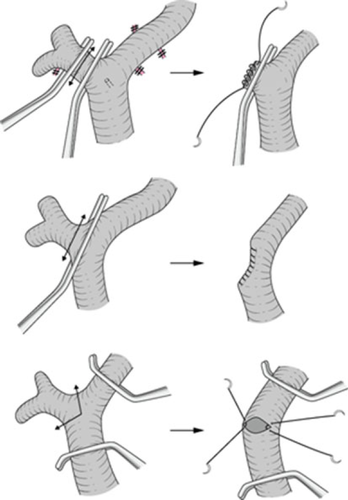

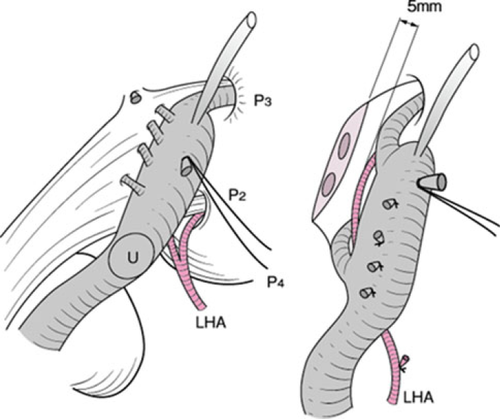

In patients in whom there is no tumor involvement of the portal vein, the right portal vein can be divided under clamping and oversewn using a 5-0 vascular suture (Fig. 4, upper).

If the right portal vein has to be divided without sufficient length from the portal bifurcation, it should be cut under cross-clamping of the main trunk of the portal vein and its left branch. Then the cut end of the right portal vein is sutured in the short axial direction using a 6-0 vascular suture (Fig. 4, lower). A longitudinal suture often results in a crooked and stenosed shape of the portal vein (Fig. 4, middle).

If the tumor involves the portal bifurcation, portal vein resection and reconstruction is performed at the final stage of this operation, i.e. after both hepatic parenchymal dissection and dissection of the left hepatic duct. Only an expert surgeon can perform portal reconstruction before hepatic resection 12. A 3-cm sleeve resection of the portal bifurcation can be restored without a vein graft. Portal reconstruction can be performed by the intraluminal technique using 6-0 vascular sutures. This technique has broad utility and must be mastered. If the length of portal vein resection is expected to exceed 3 cm, an autograft from the left renal vein 13 or internal jugular vein should be prepared.

Mobilization of the liver

The ligamentum teres is divided, and the falciform ligament is incised and separated from the anterior abdominal wall, then the right triangular ligament is incised. To mobilize the right lobe, dissection between the liver and the diaphragm is completed. The left triangular ligament is left intact in order to fix the future remnant liver. The right lobe of the liver is gradually turned left. The right adrenal gland may adhere to the right lobe of the liver, and thus is divided under clamping and oversewn using a 4-0 vascular suture (Fig. 5). The vena cava ligament is then divided. The right hepatic vein can be encircled by a tape.

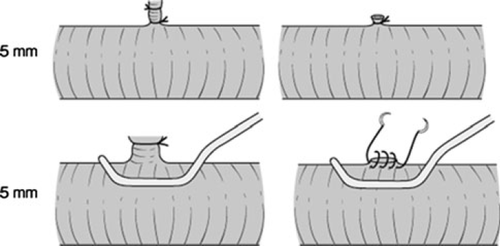

Complete exposure of the inferior vena cava is required after division of the short hepatic veins. If the short hepatic vein is thick (more than 5 mm in diameter), it is divided under cross-clamping using a Satinsky vascular clamp (Fig. 6). A full turn of the liver may induce ischemia of the hepatic parenchyma. A break is necessary to avoid unexpected liver damage.

Dissection of the ligamentum venosum and mobilization of the left caudate lobe

The left caudate lobe is then mobilized. In some patients with a hypertrophied left caudate lobe, the left edge of the caudate lobe has to be clamped using a Satinsky clamp, and divided and oversewn using a 4-0 vascular suture (Fig. 7). The cranium of the ligamentum venosum is then ligated and divided. The shoulder of the left caudate lobe can be mobilized, and the whole caudate lobe is free from the inferior vena cava.

Dissection of the liver

Parenchymal transection of the liver can be performed in several fashions. A tissue fracture technique or the use of an ultrasonic dissector and bipolar coagulator are popular. The portal vein and left hepatic artery are intermittently occluded during parenchymal transection.

Parenchymal dissection is started along the demarcation line on the liver surface. When the middle hepatic vein emerges from the liver parenchyma, the dissection should proceed along its right margin. Intraoperative ultrasonography is performed to identify the middle hepatic vein and to secure it within the future remnant liver. The branches from segment V and VIII are ligated and divided.

The parenchyma is then divided posteriorly to the middle hepatic vein just anterior to the ligamentum venosum. To ensure the direction to the ligamentum venosum, the operator can hold the caudate lobe in the left hand, so that the parenchymal dissection is performed toward the operator's fingertips (Fig. 8). Alternatively, a hanging maneuver 14 is useful (Fig. 9). The parenchymal dissection proceeds naturally to the right side of the U-point. This maneuver of the liver can also reduce blood loss during parenchymal transection. Finally, the right hepatic vein is divided. The stump is closed with an over-and-over 4-0 vascular suture or a vascular stapler.

Hemostasis is secured by the application of sutures to any obvious hemorrhage from the cut surface. A sheet of fibrin sealant (TachoComb®) and/or Argon Beam Coagulator is used for additional hemostasis.

Transection of the hilar plate

The left sheath (hilar plate) should be transected just to the right side of the U-point (Fig. 10). At that time, the hilar side of the left hepatic duct must be clamped to avoid spillage of the contaminated bile. A stay suture should be put on the distal end of the left hepatic duct. The cut end of the left hepatic duct is sent for frozen section analysis. Bleeding from the cut end of the left hepatic duct is stopped by sutures using a 6-0 vascular suture.

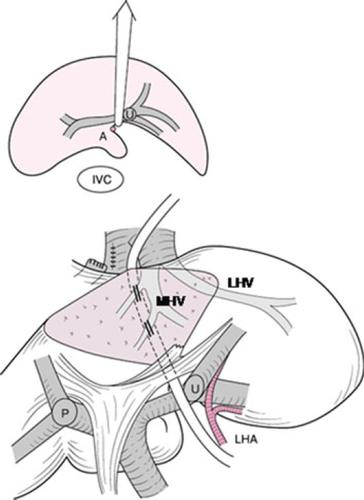

Right trisectionectomy

If the tumor extends up to the second biliary radicles, right trisectionectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1) should be applied 15 (Fig. 11). All portal branches to the medial section are transected. Consequently, the umbilical portion of the left portal vein can be turned left and several portal branches to the medial section should be transected. The umbilical plate is then transected just to the left side of the umbilical portion (Fig. 12).

Usually, one or two bile ducts (segments II and III) emerge on the cut end of the umbilical plate. The operator must pay attention to the left hepatic artery passing between the umbilical portion and left hepatic duct. A length of at least 5 mm from the cut end of the left hepatic duct should be secured to obtain a margin to sew up.

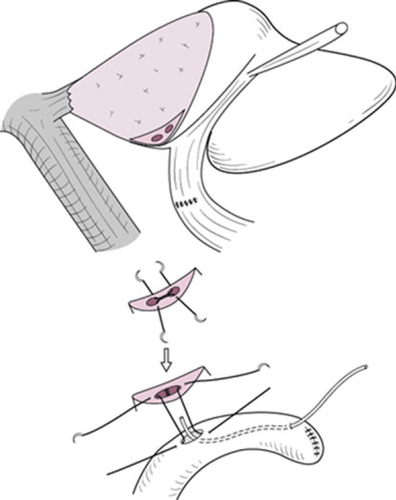

Biliary reconstruction

When the left hilar plate is transected at the right side of the U-point, two or three orifices emerge. As the dissection level of the hilar bile ducts gets higher, the number of bile duct orifices increase and the wall of the bile ducts becomes thin. Careful and gentle sutures using fine needles is mandatory for safe bilio-enteric anastomosis.

These ductal orifices may be approximated using 5-0 absorbable sutures prior to the bilio-enteric anastomosis (Fig. 13). A Roux-en-Y loop of the jejunum is brought up in a retrocolic fashion.

Stay sutures on the anterior wall of the bile duct may help to obtain an adequate view of the posterior ductal wall. The posterior row of sutures is placed from the patient's left and working toward the right using 5-0 absorbable sutures with 1–2 mm of margin to sew up. When the patient has a thin ductal wall, the margin for sewing up must be widened. While the operator is putting a suture on the posterior ductal wall, attention must be paid to the left hepatic artery and the left portal vein just beneath the posterior ductal wall.

Four to 6Fr transanastomotic biliary stents are placed through the jejunal limb. They are fixed to the ductal wall.

Closure of the abdomen

Two closed suction drains are placed posterior to the pancreatic head and right subphrenic space. A transjejunal feeding tube is placed for early enteral nutrition after surgery. The ligamentum teres is fixed to the anterior wall of the abdomen to avoid torsion of the remnant liver.

Discussion

In the 1970s, resectability was low (13–31%) in carcinoma of the hilar area and proximal bile ducts [16-19]. As anatomical knowledge of the hepatic hilum accumulated and surgical procedures were established, resection rates of hilar cholangiocarcinoma increased in the following decades [4, 20]. However, curative resection was still not possible in most cases. Surgical resection with negative margin became the next goal of hepatobiliary surgeons. Mizumoto 4 emphasized the anatomical importance of the caudate lobe based on anatomical study and showed that the potentially curative resection rate is higher in patients with combined caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1). Nimura et al. 1 also demonstrated the feasibility of various kind of hepatic segmentectomy with complete caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1). Sugiura et al. 21 indicated the survival superiority of combined caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1) in a multi-institutional study. Thus, hepatectomy with complete resection of the caudate lobe became defined as the standard operative procedure worldwide 22.

Due to the proximity of the tumor to major vascular structures, hilar cholangiocarcinoma often involves the portal bifurcation. Resection of hilar vessels was another issue in accomplishing curative resection. Introduction of vascular surgical techniques helped to increase resectability 23. Recently, hepatectomy with en bloc portal vein resection has been performed in many institutions [24-26]. Kondo et al. 12 advocated the advantage of portal vein reconstruction prior to hepatectomy without dissecting the hilar tumor from the portal vein. Furthermore, they emphasized that routine no-touch resection of the portal bifurcation in right hepatectomy was feasible and safe 27. Basically, this procedure contains potential hazards; all procedures should be performed carefully and gently

Although many surgeons have emphasized the importance of major hepatectomy in terms of curative resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer, this procedure results in a high incidence of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Portal embolization was introduced in 1990 to increase the safety of major hepatectomy for hilar bile duct carcinoma 11. Nagino et al. 28 performed PVE in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma who were to undergo right hepatectomy or right or left trisectionectomy. Routine use of preoperative portal embolization may play a role in decreasing hospital mortality [5, 6]. Kawasaki reported a low in-hospital mortality (1 of 79) even with extended hepatectomy. However, hepatic lobectomy with vascular resection still results in high operative mortality [25-27, 29-31] (Table 1). Postoperative portal vein thrombosis is one of the severe complications after portal reconstruction. Further improvement of perioperative management is needed to reduce operative mortality in such instances.

| Authors | N | R0 | Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nimura et al. 25 | 29 | 17.2 (5/29) | |

| Neuhaus et al. 26 | 23 | 14/23 | 17.4 (4/23) |

| Ebata et al. 29 | 52 | 9.6 (5/52) | |

| Miyazaki et al. 30 | 41 | 19/34a | 8.8 (3/34) |

| Hirano et al. 27 | 64 | 62/64 | 4.7 (3/64) |

| Hemming et al. 31 | 42 | 5.0 |

- a Portal vein resection alone

Several authors recommended right hemihepatectomy as a suitable type of hepatectomy for Bismuth type II tumors. Kawasaki et al. 5 performed extended right hemihepatectomy routinely for all patients with Bismuth I, II, IIIa, and IV according to several anatomical considerations. The left hepatic duct is longer than the right hepatic duct, and the right hepatic artery passes behind the common hepatic duct, thus the right hepatic artery is frequently involved by the tumor. Caudate lobe resection can be carried out more easily in patients undergoing right-sided than left-sided hepatectomy. Portal vein resection can be performed more easily with the left than the right portal vein. Kondo et al. 6 also emphasized the superiority of right hemihepatectomy because it most likely enabled en-bloc resection of the hepatic ductal confluence and its surrounding structures. However, left hepatectomy should be indicated in patients in whom the left hepatic duct was dominantly invaded. Patients with small left hemiliver (<25%) should also be treated by left hemihepatectomy 5.

Precise anatomical studies of the hepatic hilum have improved diagnostic and surgical outcomes. Direct cholangiography through the PTBD catheter was thought to be the most reliable diagnostic modality in the 1990s 1. However, it is not accurate enough to provide precise information about longitudinal cancer extension. Recent progress in imaging of hepatobiliary pancreatic disease has led to the development of multi-detector-row computed tomography (MDCT) 32 with 3D imaging. Although 3D cholangiography provides superior images of intraluminal tumor spread, it has a flaw concerning extraluminal infiltration to the surrounding tissues. On the other hand, multiplanar reconstructed images (MPR) have better diagnostic power for extraluminal, i.e., vertical invasion of the tumor, than 3D images and conventional axial 2D images alone. Thus, 3D imaging with complimentary use of MPR have led to a better topological understanding of tumor-vascular tree relations in the individual patient. It is therefore expected that margin-negative resection could be increased by the induction of 3D reconstructive imaging complimentary with MPR.

In conclusion, an aggressive surgical approach, right hemihepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (segmentectomy 1), may increase the number of patients eligible for curative resection, and thus should be the standard procedure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma except for patients with small left hemiliver or impaired liver function. Portal vein reconstruction is often required for en-bloc resection. Further pursuit of safe and careful surgical procedures is mandatory.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.