Cutting-edge information for the management of acute pancreatitis

Abstract

Considering that the Japanese (JPN) guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis were published in Takada et al. (J HepatoBiliary Pancreat Surg 13:2–6, 2006), doubts will be cast as to the reason for publishing a revised edition of the Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: the JPN guidelines 2010, at this time. The rationale for this is that new criteria for the severity assessment of acute pancreatitis were made public on the basis of a summary of activities and reports of shared studies that were conducted in 2008. The new severity classification is entirely different from that adopted in the 2006 guidelines. A drastic revision was made in the new criteria. For example, about half of the cases that have been assessed previously as being ‘severe’ are assessed as being ‘mild’ in the new criteria. The JPN guidelines 2010 are published so that consistency between the criteria for severity assessment in the first edition and the new criteria will be maintained. In the new criteria, severity assessment can be made only by calculating the 9 scored prognostic factors. Severity assessment according to the contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) grade was made by scoring the poorly visualized pancreatic area in addition to determining the degree of extrapancreatic progress of inflammation and its extent. Changes made in accordance with the new criteria are seen in various parts of the guidelines. In the present revised edition, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis is treated as an independent item. Furthermore, clinical indicators (pancreatitis bundles) are presented to improve the quality of the management of acute pancreatitis and to increase adherence to new guidelines.

Introduction

The first edition of the JPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis was published in 2006 in the journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery 2006;13:2–6 [1]. Looking back at the circumstances until the publication of the present English-language version, the results of longtime endeavor by the working group for developing the JPN guidelines become apparent. The first Japanese edition of the Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis was published in 2003 [2].

In 1994, the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine organized a working group involved in the preparation of guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. The first Japanese edition of the Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis was published owing to the painstaking activities on the part of the working group, including a search for systematic evidence and the preparation of a definite statement of recommendations along with the levels of the recommendations and a flow chart. A second edition was published 4 years after the publication of the first edition. During the 4 years after the publication of the first edition in 2003, the mortality rate of acute pancreatitis in Japan was reduced from 7.2 to 2.9%, although it exceeded 30% in the most severe cases. Under these circumstances, aid for medical expenses is provided for specified intractable diseases in Japan.

Doubts will be cast as to the reason for publishing a revised edition of the Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: the JPN guidelines 2010, at this time. The rationale for this is that new criteria for the severity assessment of acute pancreatitis were made public on the basis of activities and reports of shared studies that were conducted in 2008. The new severity classification is entirely different from that adopted in the 2006 guidelines. A drastic revision was made in the new criteria. For example, about half of the cases that have been assessed previously as being ‘severe’ are assessed as being ‘mild’ in the new criteria. The JPN guidelines 2010 are published so that consistency between the criteria for severity assessment in the first edition and the new criteria will be maintained. In the present new criteria, severity assessment can be made only by calculating the 9 scored prognostic factors. Severity assessment according to the contrast-enhanced CT grade was made by scoring the poorly visualized pancreatic area in addition to determining the degree of extrapancreatic progress of inflammation and its extent. Revisions made in accordance with the new criteria are seen in various parts of the guidelines. In the present revised edition, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis is treated as an independent item. Furthermore, clinical indicators (pancreatitis bundles) are presented to improve the quality of management of acute pancreatitis and increase adherence to guidelines.

The Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Pancreas Society, the Research Group (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare) for Intractable Diseases and Refractory Pancreatic Diseases (under the sponsorship of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare), the Japanese Radiological Society, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery were commissioned to produce the JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis.

The overall contents of the JPN Guidelines 2010 for the management of acute pancreatitis

The JPN Guidelines 2010 for the management of acute pancreatitis, to be published in the Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences (J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;1) are divided into the following 11 topics.

- Tadahiro Takada, et al. Cutting-edge information for the management of acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

-

Masahiro Yoshida et al. Health insurance and payment systems for severe acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

The Universal Medical Care Insurance system, which is a unique health insurance system of Japan, is described.

-

Miho Sekimoto, et al. National survey of effect of clinical practice guidelines for acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

Changes in the management of acute pancreatitis after the publication of the first edition of the JPN Guidelines are presented mainly on the basis of the results of questionnaire research.

-

Seiki Kiriyama, et al. New diagnostic criteria of acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

In making a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, reference is often made to cut-off values of serum pancreatic enzymes, such as a level that is elevated by more than 3 times the normal range. However, due to the lack of definite evidence of the relevance of these values, discussion of these cut-off values was excluded. Furthermore, the diagnostic shortcomings of an elevated level of serum amylase are referred to, and the reason for inclusion of the significance of serum lipase tests is presented.

- Kazunori Takeda, et al. Assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis according to new prognostic factors and CT grading: JPN Guidelines 2010 Severity assessment made according to the scored prognostic factors and the contrast-enhanced CT grading is discussed. The severity assessment made according to two methods is described by comparison with the old severity scoring used in the first edition. For those cases that have been assessed as being severe according to the prognostic factors of either of the two methods, the mortality rate can be calculated more clearly when severity assessment is made by combination with the contrast-enhanced CT grade.

- Morihisa Hirota, et al. Fundamental and intensive care of acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010 Description is focused on the basic treatment policy for acute pancreatitis (fluid replacement, nasogastric tube, nutrition, antibiotics, and protease inhibitors. Also described as special treatment are selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD), continuous hemodiafiltration (CHDF), continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitors, and the use of antibiotics.

- Hodaka Amano, et al. Therapeutic intervention and surgery for acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010 Changes in operative indications for acute pancreatitis, necrotizing pancreatitis, and infected pancreatitis are discussed in particular.

-

Yasutoshi Kimura, et al. Gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

Description is focused on the algorithm of gallstone-induced pancreatitis.

-

Shinju Arata, et al. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

Assessment of post-ERCP pancreatitis as an independent item; its epidemiology, risk factors, and diagnosis are described.

-

Keita Wada, et al. Strategy for the management of acute pancreatitis: JPN Guidelines 2010

By means of a flow chart, explanation is given that shows how to cope with patients in whom acute pancreatitis is suspected or those with a definitive diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. The flow chart for the management of gallstone-induced pancreatitis is presented independently.

-

Toshihiko Mayumi, et al. Pancreatitis bundles: JPN Guidelines 2010

Current characteristics of other bundles and pancreatitis bundles are presented.

Categories of evidence and the grading of recommendations

The evidence obtained from each reference item was evaluated in accordance with the method of scientific classification used at the Cochrane Library (March, 2009) (Table 1) [1-3], and the quality of evidence for each parameter associated with the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis was determined. The relevant terms used are explained in the footnote of Table 1 [13]. Based on the results obtained from these procedures, recommendation grades of A–D were determined according to the definitions shown in Table 2, and the recommendation grades are mentioned, as required, in the text of the Guidelines. The grading is based on the classification of the modified Tokyo guidelines [4].

Recommendations graded as either A or B indicate high quality. Grade C1 shows that the use of the procedures may be considered, although there is only a small amount of scientific evidence for them. On the other hand, Grade C2 shows that the use of the procedures cannot be definitely recommended due to lack of a sufficient amount of scientific evidence. Procedures graded as D are considered to be unacceptable. It must be borne in mind that such recommendation grades merely represent standards and should not be used to compel adherence to a given method of medical management in an actual clinical setting. The medical management method that is applied should be selected after taking into account the conditions prevailing at the relevant institution (e.g., staff, experience, and equipment) and the characteristics of the individual patient.

| Level | Therapy/prevention, etiology/harm | Prognosis | Diagnosis | Differential diagnosis/symptom prevalence study | Economic and decision analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | SR (with homogeneitya) of RCTs | SR (with homogeneitya) of inception cohort studies; CDRb validated in different populations | SR (with homogeneitya) of level 1 diagnostic studies; CDRb with lb studies from different clinical centers | SR (with homogeneitya) of prospective cohort studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of level 1 economic studies |

| 1b | Individual RCT (with narrow confidence intervalc) | Individual inception cohort study with >80% follow-up; CDRb validated in a single population | Validatingk cohort study with goodi reference standards; or CDRb tested within one clinical center | Prospective cohort study with good follow-upm | Analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; systematic review(s) of the evidence; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses |

| 1c | All or noned | All or none case-series | Absolute SpPins and SnNoutsg | All or none case-series | Absolute better-value or worse-valueh analysesj |

| 2a | SR (with homogeneitya) of cohort studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of either retrospective cohort studies or untreated control groups in RCTs | SR (with homogeneitya) of level >2 diagnostic studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of 2b and better studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of level >2 economic studies |

| 2b | Individual cohort study (including low-quality RCT; e.g., <80% follow-up) | Retrospective cohort study or follow up of untreated control patients in an RCT; Derivation of CDRb or validated on split-samplef only | Exploratoryk cohort study with goodi reference standards; CDRb after derivation, or validated only on split-samplef or databases | Retrospective cohort study, or poor follow up | Analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; limited review(s) of the evidence, or single studies; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses |

| 2c | “Outcomes” Research; Ecological studies | “Outcomes” Research | Ecological studies | Audit or outcomes research | |

| 3a | SR (with homogeneitya) of case–control studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of 3b and better studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of 3b and better studies | SR (with homogeneitya) of 3b and better studies | |

| 3b | Individual case–control study | Non-consecutive study; or without consistently applied reference standards | Non-consecutive cohort study, or very limited population | Analysis based on limited alternatives or costs, poor quality estimates of data, but including sensitivity analyses incorporating clinically sensible variations | |

| 4 | Case-series (and poor quality cohort and case–control studiese) | Case-series (and poor quality prognostic cohort studiel) | Case-control study, poor or non-independent reference standard | Case-series or superseded reference standards | Analysis with no sensitivity analysis |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on economic theory or “first principles” |

- Produced by Bob Phillips, Chris Ball, Dave Sackett, Doug Badenoch, Sharon Straus, Brian Haynes, Martin Dawes since November 1998. Updated by Jeremy Howick March 2009

- Users can add a minus-sign “–” to denote the level of a study that fails to provide a conclusive answer because there is

- EITHER a single result with a wide confidence interval OR a systematic review with troublesome heterogeneity

- Such evidence is inconclusive, and therefore can only generate Grade D recommendations

- a By homogeneity we mean a systematic review that is free of worrisome variations (heterogeneity) in the directions and degrees of results between individual studies. Not all systematic reviews with statistically significant heterogeneity need be worrisome, and not all worrisome heterogeneity need be statistically significant. As noted above, studies displaying worrisome heterogeneity should be tagged with a “–” at the end of their designated level

- b Clinical Decision Rule. (These are algorithms or scoring systems that lead to a prognostic estimation or a diagnostic category.)

- c See note above for advice on how to understand, rate, and use trials or other studies with wide confidence intervals

- d Met when all patients died before the treatment (Rx) became available, but some now survive on it; or when some patients died before the Rx became available, but none now die on it

- e By poor quality cohort study we mean one that failed to clearly define comparison groups and/or failed to measure exposures and outcomes in the same (preferably blinded), objective way in both exposed and non-exposed individuals and/or failed to identify or appropriately control known confounders and/or failed to carry out a sufficiently long and complete follow up of patients. By poor quality case–control study we mean one that failed to clearly define comparison groups and/or failed to measure exposures and outcomes in the same (preferably blinded), objective way in both cases and controls and/or failed to identify or appropriately control known confounders

- f Split-sample validation is achieved by collecting all the information in a single tranche, then artificially dividing this into “derivation” and “validation” samples

- g An “Absolute SpPin” is a diagnostic finding whose Specificity is so high that a Positive result rules-in the diagnosis. An “Absolute SnNout” is a diagnostic finding whose Sensitivity is so high that a Negative result rules-out the diagnosis

- h Good, better, bad, and worse refer to the comparisons between treatments in terms of their clinical risks and benefits

- i Good reference standards are independent of the test, and are applied blindly or objectively to all patients. Poor reference standards are haphazardly applied, but still independent of the test. Use of a non-independent reference standard (where the ‘test’ is included in the ‘reference’, or where the ‘testing’ affects the ‘reference’) implies a level 4 study

- j Better-value treatments are clearly as good but cheaper, or better at the same or reduced cost. Worse-value treatments are as good and more expensive, or worse and equally or more expensive

- k Validating studies test the quality of a specific diagnostic test, based on prior evidence. An exploratory study collects information and trawls the data (e.g. using a regression analysis) to find which factors are ‘significant’

- l By poor quality prognostic cohort study we mean one in which sampling was biased in favor of patients who already had the target outcome, or the measurement of outcomes was accomplished in <80% of study patients, or outcomes were determined in an unblinded, non-objective way, or there was no correction for confounding factors

- m Good follow up in a differential diagnosis study is >80%, with adequate time for alternative diagnoses to emerge (for example, 1–6 months acute; 1–5 years chronic)

| Grade of recommendation | Contents |

|---|---|

| A | Recommended strongly to perform |

| Evidence is strong and clear clinical effectiveness can be expected | |

| B | Recommended to perform |

| Evidence is moderate or strong, although evidence of effectiveness is sparse | |

| C1 | Evidence is sparse, but may be considered to perform |

| Effectiveness can possibly be expected | |

| C2 | Scientific evidence is not sufficient, so clear recommendation cannot be made |

| Evidence is not sufficient to support or deny effectiveness | |

| D | Considered to be unacceptable |

| There is evidence to deny effectiveness (to show harm) |

- The Minds Manual for Preparation of Management Guidelines [2007 edition] (included as a reference after translation into English) cited with modifications from the Tokyo Guidelines [4]

The quality of evidence in each item related to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was determined on the basis of the assessment of evidence introduced in each reference according to the evidence-based classification adopted in the Cochrane library (Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine and Levels of Evidence) (March, 2009) [1-3]. The levels of evidence in all the references cited in the present Guidelines are shown in parentheses at the end of each reference in the reference list.

The grades of recommendation were determined and included as appropriate in the present guidelines by considering medical circumstances in Japan (characteristics of medical practice and the insurance system) and in reference to the level of evidence obtained from each reference and the grades of recommendation shown in Table 2. In making use of the grades of recommendation in actual situations, consider the notes that are included as appropriate.

Note that the above recommendations are the most standardized criteria, but that the present guidelines have no intention of compelling the use of the recommendations in actual medical practice. The final decision should be made after having taken into consideration the condition of facilities (e.g., personnel, experience, and equipment)and circumstances that individual patients are placed in.

Procedures can be rated as Grade A or B, in which performance is recommended. On the contrary, the performance of procedures rated as Grade D is not recommended. As for Grade C, Grade C1 suggests that effectiveness can be expected although there is only a small amount of scientific evidence, while Grade C2 suggests that there is an insufficient amount of scientific evidence to support or deny effectiveness.

Notes on the use of the guidelines

The Guidelines are evidence-based and determined with a grade for each medical practice, taking actual conditions into account. The Guidelines specify the criteria for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and the assessment of its severity that have been prepared by the Research Group and are in widespread use in Japan. Because the Guidelines address so many different topics, an index of all works used is included at the end of the Guidelines. Dosages described in the text of the guidelines are for adult patients.

Definition of terminology

A certain degree of consensus has been obtained to date concerning the definition of acute pancreatitis and its complications, in reference to the guidelines of international conferences in Marseilles (1963) [5], Cambridge (1983) [6], Marseilles (1984) [7], Marseilles-Rome (1988) [8], and Atlanta (1992) [9], as well as the guidelines of the Intractable Pancreatic Disease Investigation and the Research Group of the Japanese Ministry of Health, and Welfare (1987) [10] and those of the British Society of Gastroenterology 1998) [11]. However, there remain many ambiguous elements in the definitions of terminology associated with acute pancreatitis, so new terminology is proposed below.

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is defined as an inflammation that has occurred in the pancreas and that can affect remote organs as well as the adjacent organs. It was decided that acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis should be dealt with in separate items according to the causes that give rise to acute pancreatitis (such as acute alcoholic pancreatitis and gallstone-induced pancreatitis).

Clinical features of acute pancreatitis

In most cases, acute pancreatitis occurs suddenly and is accompanied by upper abdominal pain and various types of abdominal manifestations (from mild tenderness to rebound pain). It is often accompanied by vomiting, fever, tachycardia, and elevated levels of white blood cells and blood or urinary pancreatic enzymes.

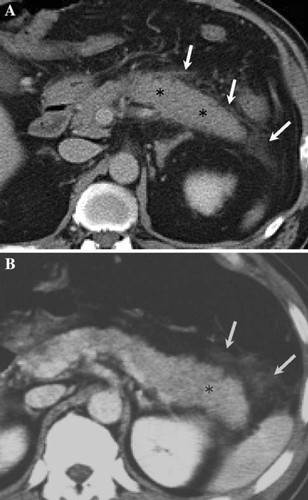

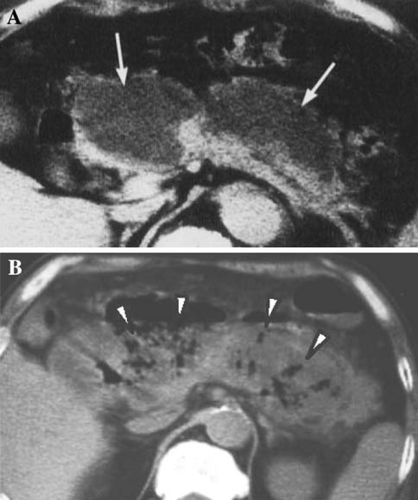

Acute edematous pancreatitis (Fig. 1)

Pancreatitis usually results in diffuse or localized enlargement of the pancreas along with inflammation. Although edematous pancreatitis induces necrosis in severe cases, it is defined as that type of pancreatitis not accompanied by necrosis.

Clinical features

Edematous pancreatitis has no area in which there is no infection according to contrast-enhanced CT, although enlargement of the pancreas is observed.

Acute fluid collection (Fig. 2)

Acute fluid collection is defined as exudate collection that often occurs within the pancreas or in the parapancreatic tissue in the early phase of the disease. It may progress as far as the anterior paraphrenic cavity, the mesocolon, and beyond the inferior renal portion. It is also characterized by lack of the fibrous wall.

Clinical features

Although acute exudate collection occurs in 30–50% of patients, spontaneous resolution is achieved in half of them (level 4) [12, 13]. Clinical differentiation from pseudocysts is made according to the presence or absence of the cystic wall. Pleural fluid, ascites, and fluid collection as far as the cavity of the omental bursa occur as a reaction against inflammation, so these features are not defined as acute exudate collection.

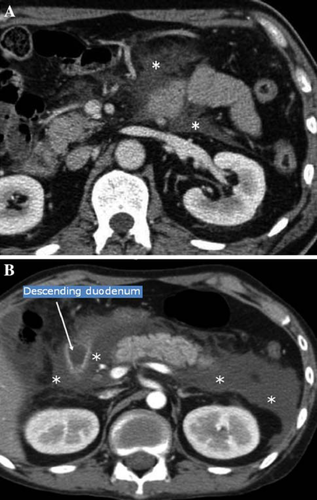

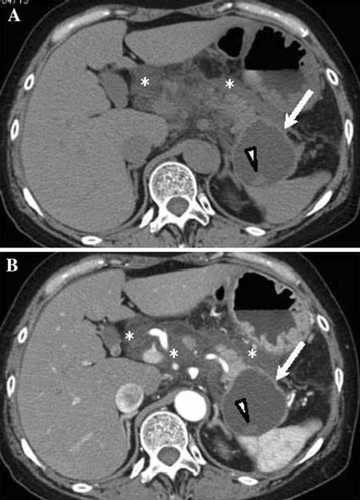

Necrotizing pancreatitis (Fig. 3)

Pancreatic necrosis is defined as diffuse or localized necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma and is differentiated from necrosis occurring around the pancreas and that of extrapancreatic adipose tissue [14, 15]. However, pancreatic necrosis is often accompanied by necrosis around the pancreatic adipose tissue. Clinically, in cases of pancreatic necrosis, a poorly visualized area of the pancreatic parenchyma is observed distinctly by contrast-enhanced CT. However, there have been reports in recent years pointing out that the detection of a poorly visualized area by contrast-enhanced CT does not necessarily suggest the presence of necrosis in all the cases involved and that detection of an area that is not visualized, particularly in the acute phase, may suggest the presence of temporary ischemia, which can be reversible [14, 16].

Clinical features

A marked difference is observed in the mortality rate depending upon the presence or absence of infectious complications in the necrotizing pancreatic tissue (level 4) [17], so the differentiation between infected and noninfected pancreatitis is important.

Infected pancreatic necrosis (Fig. 4)

Infected pancreatic necrosis is the type of necrosis that is complicated by infections such as bacterial infections in the pancreatic parenchyma and parapancreatic tissue [14]. There are not a few cases in which differentiation from noninfected pancreatic necrosis is difficult, so a bacterial culture by fine needle aspiration (FNA) under imaging guidance is required to make the diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis.

Clinical features

A marked difference is observed in the mortality rate depending upon the presence or absence of infectious complications in the necrotizing pancreatic tissue (level 4) [17]; the prognosis of necrotizing pancreatitis is reported to be poor when it is accompanied by infections in the necrotic tissue (34–40%) [18, 19].

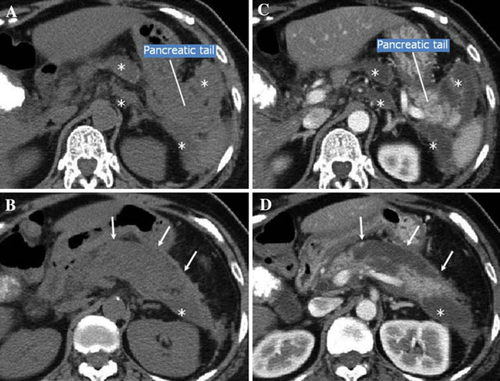

Pancreatic pseudocyst (Fig. 5)

Irrespective of the presence or absence of a communication between the pseudocyst and the pancreatic duct, pancreatic pseudocyst is defined as the type of pseudocyst with a wall structure of granulation or fibrotic tissue. It is accompanied by the collection of pancreatic juice and the tissue of liquefaction necrosis, and often occurs 4 weeks after the onset of acute pancreatitis. It may resolve spontaneously, although it may persist for a long time. It may be complicated by infections or bleeding.

Clinical features

In patients with acute pancreatitis, a pseudocyst can be detected by diagnostic imaging, as well as by palpation. The pseudocyst usually contains large amounts of pancreatic enzymes, although in many cases pseudocysts do not contain bacteria.

Pancreatic abscess (Fig. 6)

Pancreatic abscess is the type of abscess that is accompanied by localized pus collection in the pancreas and adjacent organs. However, there is usually no necrosis within the pancreas, or there is only a small amount if any. Because pancreatic abscess consists of necrotic tissue as well as liquid components, there are indications that it is induced by the liquefaction of tissue necrosis [14, 15].

Clinical features

Pancreatic abscess presents with a wide spectrum of clinical pictures, although it also presents with pictures of infections in many patients. It often occurs 4 weeks after the onset of severe acute pancreatitis. Differentiation between pancreatic abscess and infected pancreatic necrosis is often difficult, and it is reported, according to present knowledge, that their mortality rates are almost the same [20]. An abscess that has occurred following an operation for acute pancreatitis should be assessed as a postoperative abscess and differentiated from an abscess that has occurred while the disease is being managed conservatively.

Alcoholic pancreatitis

Alcoholic pancreatitis is defined as acute pancreatitis associated with alcohol consumption; however, there is no report to date that has defined alcoholic pancreatitis clearly. It is thought that mechanisms involved in its occurrence include contraction of the Oddi sphincter, obstruction of the pancreatic duct due to the sedimentation of an insoluble protein plug, and activated pancreatic protease. Genetic mutation and smoking are also reported to be cofactors that induce pancreatitis [21].

Gallstone-induced pancreatitis

Gallstone-induced pancreatitis is defined as acute pancreatitis caused by gallstones. Although its mechanism is not known, it is assumed that it can be induced by obstruction of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, which can occur when gallstones are excreted into the duodenum through the common bile duct. Findings that suggest the presence of biliary sludge (obstructive jaundice) are often observed. There can be a complication of cholangitis. Edema of the Vater papilla after gallstones have been excreted, as well as obstruction of the bile duct and pancreatic duct, is also assumed to cause gallstone-induced pancreatitis [22, 23].