The influence of illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related factors on real-life functioning of people with schizophrenia

Abstract

In people suffering from schizophrenia, major areas of everyday life are impaired, including independent living, productive activities and social relationships. Enhanced understanding of factors that hinder real-life functioning is vital for treatments to translate into more positive outcomes. The goal of the present study was to identify predictors of real-life functioning in people with schizophrenia, and to assess their relative contribution. Based on previous literature and clinical experience, several factors were selected and grouped into three categories: illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related factors. Some of these variables were never investigated before in relationship with real-life functioning. In 921 patients with schizophrenia living in the community, we found that variables relevant to the disease, personal resources and social context explain 53.8% of real-life functioning variance in a structural equation model. Neurocognition exhibited the strongest, though indirect, association with real-life functioning. Positive symptoms and disorganization, as well as avolition, proved to have significant direct and indirect effects, while depression had no significant association and poor emotional expression was only indirectly and weakly related to real-life functioning. Availability of a disability pension and access to social and family incentives also showed a significant direct association with functioning. Social cognition, functional capacity, resilience, internalized stigma and engagement with mental health services served as mediators. The observed complex associations among investigated predictors, mediators and real-life functioning strongly suggest that integrated and personalized programs should be provided as standard treatment to people with schizophrenia.

Despite significant advances in pharmacological and psychological treatments, schizophrenia still ranks among the first ten leading causes of disability worldwide. It has a direct negative influence on the real life of about 26 millions of people and an indirect negative impact on more than twice this number when considering patients' relatives and caregivers 1. Major areas of everyday life are impaired, including independent living, productive activities and social relationships 2.

The lessening of symptoms and the reduction of relapse rate contributes to improve real-life functioning, but is not sufficient to attain functional recovery 3-6. Enhanced understanding of factors that hinder functioning in schizophrenia is vital for treatments to translate into more positive outcomes 7. Studies carried out so far have led to partial and sometimes discrepant findings. Furthermore, they usually focused on neurocognitive deficits, negative symptoms and depression, and often failed to simultaneously consider several relevant variables 8-10.

For neurocognitive impairment, small to large correlations with global indices of functioning have been reported, depending on the investigated domains, the use of a composite score (higher correlations for the composite score than for individual cognitive domains) and the rater of patient functioning (higher correlations for clinician rating than for patient self-report) 11, 12. Recent studies have shown that the impact of neurocognitive impairment may be mediated by functional capacity, i.e., the ability to perform tasks relevant to everyday life in a structured environment, guided by an examiner. In some studies, the impact of cognitive impairment on real-life functioning was negligible when functional capacity was included in the model 13, 14. Discrepant results have also been reported, i.e., no correlation between neurocognitive indices or functional capacity and self-reported real-life functioning 15, or a significant influence of neurocognitive dysfunction on everyday-life functioning in the presence of no influence of functional capacity 16.

Social cognition is currently considered a domain partly independent of neurocognitive functions and encompassing a large array of mental functions, from social perception to affect recognition, to theory of mind 17, 18. Relationships between deficits in social cognition and impaired social and occupational functioning have been reported 17, 19, 20. According to some studies, social cognition mediates the effect of neurocognitive impairment on real-life functioning 21, 22.

Negative symptoms have also been associated with patients' functional outcome 9, 23, 24. Both direct and indirect relationships between this psychopathological domain and real-life functioning have been reported 7, 13. Evidence of the role of negative symptoms as mediators of the impact of other variables (i.e., neurocognition or functional capacity) on real-life functioning has also been provided 9, 25. However, several limitations of previous studies might prevent solid conclusions and generalizability. In fact, negative symptoms have generally been regarded as a unitary construct, while the most recent literature suggests that these symptoms are heterogeneous and include at least two factors, “avolition” and “poor emotional expression”, that might be underpinned by different pathophysiological substrates 26, 27 and show different relationships to functional outcome 23. Moreover, largely used scales for the assessment of negative symptoms have been criticized for the inclusion of items assessing neurocognition and the focus on behavioral aspects, as opposed to internal experience, which may lead to artefactual associations with functional outcome measures 28, 29.

An impact of depressive symptoms on real-life functioning in schizophrenia has also been reported 30-32. However, an association has generally been found only when studies examined subjective indicators of real-life functioning 13, 33, suggesting that depression affects person's self-evaluation of functioning but not “real” functioning. The symptoms of depression may also affect functioning by interfering with subject's motivation and ability to properly organize him/herself in daily living activities. In this respect, the simultaneous evaluation of negative and depressive symptoms is important to clarify the relative contribution of these two psychopathological domains to real-life functioning.

Besides the variables summarized above, some studies have reported that patients with comparable severity of psychopathology may differ in their real-life functioning as a result of differences in personal resources 34-36. Resilience is a construct encompassing several aspects of personal resources. It is variously defined as a personal trait protective against mental disorders and a dynamic process of adaptation to challenging life conditions 37-40. In patients with schizophrenia, a significant correlation between resilience and psychosocial functioning has been reported 41; furthermore, lower baseline resilience was found among ultra-high risk subjects who converted to frank psychosis than among those who did not 42. Resilience is also related to patterns of mental health service engagement of patients with schizophrenia, which can affect real-life functioning 43.

Although it is obvious that real-life functioning is also influenced by the societal context, which includes disability compensation, job or housing opportunities, residential support, and various elements of attitudes and stigma 2, the identification of the most appropriate indices to capture the complexity of these variables is not an easy task. The evaluation of subjects' functioning with respect to employment or housing, for example, must take into account the offer of employment or housing in the place where the patient lives and the availability of social support, such as a disability pension. According to a recent study, differences in residential outcomes are likely based on differences in social services systems 44. Similarly, in a two-year follow-up of people with schizophrenia after their first episode, only those who were receiving disability compensation or were supported by their families were living independently 45. Indeed, it appears likely that interventions which modify the level of social support have an impact on real-life functioning in people with schizophrenia.

A higher level of internalized stigma – the process whereby people with severe mental disorders anticipate social rejection and consider themselves as devalued members of society 46-48 – has been found in association with lower levels of hope, empowerment, self-esteem, self-efficacy, quality of life, social support and adherence to treatment 49, suggesting an impact of this variable on real-life functioning, and the need to consider it in relevant studies.

From the summarized evidence, it is clear that real-life functioning of people with schizophrenia depends on a number of variables, some related to the disease, others to personal resources, and some more to the context in which the person lives. In the light of this complexity, it is crucial to consider all these aspects in order to explore their relative contribution.

In this paper we report on a large Italian multicenter study aimed to identify factors affecting real-life functioning of patients with schizophrenia and to assess their relative contribution. Factors to be included were chosen in the light of the literature review briefly summarized and of clinical experience, and were grouped into three categories: illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related variables. We predicted a significant association between the impairment of real-life functioning and the severity of negative symptoms and cognitive deficits, such as the more severe the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits, the more impaired the everyday functioning. As to negative symptoms, we expected that avolition would show a stronger association with real-life functioning than poor emotional expression. An association between neurocognition and real-life functioning was also expected, partly or entirely mediated by functional capacity and social cognition. We also hypothesized that the variables included among personal resources mediate the impact of symptoms and cognitive impairment on real-life functioning. Due to the paucity of literature data, it was more difficult to predict which context-related variables would show a direct or indirect association with real-life functioning. Nevertheless, we anticipated that a large social network and having access to social and family incentives would have a favorable impact on functioning, and that internalized stigma would mediate the influence of symptoms and cognitive deficits on functioning.

Several limitations of previous studies were addressed in the present investigation. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS, 28) was used to assess negative symptoms; this is a recently developed instrument designed to overcome the above-mentioned limitations of other largely used scales for the assessment of negative symptoms. Depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms were evaluated to ascertain their possible influence on negative symptoms and real-life functioning. The MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) was chosen for cognitive assessment, as it is regarded as the “state of the art” neuropsychological battery for research purposes in schizophrenia 50, 51. A full assessment of different aspects of social cognition was carried out, including emotional intelligence, emotion recognition and theory of mind. Personal resources and context related factors were included in the study.

In the light of difficulties in defining and measuring real-life functioning 2, the Specific Levels of Functioning Scale (SLOF) was selected to measure social, vocational, and everyday living outcomes 52. This instrument was endorsed by the panel of experts involved in the Validation of Everyday Real-World Outcomes (VALERO) initiative as a suitable measure of real-life functioning 12, 53.

Due to the high number of included variables, a large multicenter study was designed to be carried out in 26 university psychiatric clinics and/or mental health departments, recruiting up to 1000 subjects with schizophrenia.

METHODS

Participants

Study participants were recruited from patients living in the community and consecutively seen at the outpatient units of 26 Italian university psychiatric clinics and/or mental health departments. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV, confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV - Patient version (SCID-I-P), and an age between 18 and 66 years. Exclusion criteria were: a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness; a history of moderate to severe mental retardation or of neurological diseases; a history of alcohol and/or substance abuse in the last six months; current pregnancy or lactation; inability to provide an informed consent; treatment modifications and/or hospitalization due to symptom exacerbation in the last three months.

All patients signed a written informed consent to participate after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures and goals.

Procedures

Approval of the study protocol was obtained from the Local Ethics Committees of the participating centers. Recruitment took place from March 2012 to September 2013.

Enrolled patients completed the assessments in three days with the following schedule: collection of socio-demographic information, psychopathological evaluation and neurological assessment on day 1, in the morning; assessment of neurocognitive functions, social cognition and functional capacity on day 2, in the morning; assessment of personal resources and perceived stigma either on day 3 (morning or afternoon) or in the afternoon of day 1 or 2, according to the patient's preference. For real-life functioning assessment, patient's key caregiver was invited to join one of the scheduled sessions.

Assessment tools

Evaluation of illness-related factors

A clinical form was filled in with data on age of disease onset, course of the disease and treatments, using all available sources of information (patient, family, medical records and mental health workers).

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, 54) was used to rate symptom severity. Scores for the dimensions “disorganization” and “positive symptoms” were calculated based on the consensus 5-factor solution proposed by Wallwork et al 55.

Negative symptoms were assessed using the BNSS, which includes 13 items, rated from 0 (normal) to 6 (most impaired), and five negative symptoms domains: anhedonia, asociality, avolition, blunted affect and alogia. The Italian version of the scale was validated as part of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses activities. In line with previous research 28, 56, domains evaluated by the scale loaded on two factors: “avolition”, consisting of anhedonia, asociality and avolition, and “poor emotional expression”, including blunted affect and alogia.

Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS, 57), a rating scale designed to assess the level of depression in people with schizophrenia.

Extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed by means of the St. Hans Rating Scale (SHRS, 58), a multidimensional rating scale consisting of four subscales: hyperkinesias, parkinsonism, akathisia and dystonia. Each subscale includes one or more items, with a score ranging from 0 (absent) to 6 (severe).

Neurocognitive functions were rated using the MCCB. This battery includes tests for the assessment of seven distinct cognitive domains: processing speed, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, social cognition, and reasoning and problem solving.

The assessment of social cognition, partly included in the MCCB Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) managing emotion section, was integrated by the Facial Emotion Identification Test (FEIT, 59) and The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT, 60), which is a theory of mind test.

Assessment of personal resources

Resilience was evaluated by the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA, 61), a self-administered scale including 33 items that examine intra- and inter-personal protective factors thought to facilitate adaptation when facing psychosocial adversity. Items are organized in six factors: perception of self, perception of the future, structured style, social competence, family cohesion, and social resources. To avoid overlap with other measures, the “structured style” and “social resources” factors were not included in the analysis.

The Service Engagement Scale (SES, 62), an instrument including 14 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale (with higher scores reflecting greater levels of difficulty engaging with services), was used to explore patients' relationship with mental health services. Items are grouped into four subscales: availability, cooperation, help seeking, and adherence to treatment. In the present paper, we used the total score provided by the instrument.

Evaluation of context-related factors

A socio-demographic questionnaire was developed ad hoc to collect data on gender, age, marital status, schooling, housing, eating habits, substance use, socio-economic status, availability of a disability pension, and access to family and social incentives.

The socio-economic status was determined from the education level and the type of work of each parent. The education level was measured on a 7-level scale (1=elementary school, 7=post-degree/specialization courses) and the type of work was ranked on 9 levels (1=laborer, 9=high level managerial position). The Hollingshead index was calculated as the average of the indices of the two parents 63.

The Social Network Questionnaire (SNQ, 64) was used to assess structural and qualitative aspects of participants' social network. This is a self-administered questionnaire including 15 items rated on a 4-point scale (from 1 "never" to 4 "always"), organized into four factors: quality and frequency of social contacts, practical social support, emotional support, and quality of an intimate relationship.

The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI, 65) was used to evaluate the experience of stigma and internalized self-rejection. It includes 29 items and 5 subscales for self-assessment of subjective experience of stigma. Each item is rated on a 4-level Likert scale, where higher scores indicate greater levels of internalized stigma.

Assessment of functional capacity and real-life functioning

Functional capacity was evaluated using the short version of the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills Assessment Brief (UPSA-B, 66), a performance-based instrument that assesses “financial skills” (e.g., counting money and paying bills) and “communication skills” (e.g., to dial a telephone number for emergency or reschedule an appointment by telephone). The total score, ranging from 0 to 100, was used in statistical analyses.

Real-life functioning was assessed by the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF), a hybrid instrument that explores many aspects of functioning and is based on the key caregiver's judgment on behavior and functioning of patients. It consists of 43 items and includes the following domains: physical efficiency, skills in self-care, interpersonal relationships, social acceptability, community activities (e.g., shopping, using public transportation), and working abilities. Higher scores correspond to better functioning. In our study, the key relative was interviewed, as usually this is the individual most frequently and closely in contact with the patient in the Italian context. The Italian version of the scale has recently been validated 67.

Training of researchers

For each category of variables (illness-related factors, personal resources and context-related factors), at least one researcher per site was trained. In order to avoid halo effects, the same researcher could not be trained for more than one category.

The inter-rater reliability was formally evaluated by Cohen's kappa for categorical variables, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) or percentage agreement for continuous variables. An excellent inter-rater agreement was found for the SCID-I-P (Cohen's kappa=0.98). Good to excellent agreement among raters was observed for SLOF (ICC=0.55-0.99, percentage agreement=70.1-100%); BNSS (ICC=0.81-0.98); PANSS (ICC=0.61-0.96, percentage agreement=67.7-93.5%); CDSS (ICC=0.63-0.90) and MCCB (ICC=0.87).

Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants and the scale scores were summarized as mean ±SD, median and interquartile range, and percentages where appropriate.

Structural equation models (SEM) were used to test the relationships of variables inherent to illness, personal resources and context with real-life functioning. These models can be interpreted as a set of simultaneous multiple regression models, in which variables can serve as predictors or outcomes. As a preliminary step, we examined the pairwise correlation and covariance matrix for the study variables. Given the large number of cases, correlations were interpreted taking into account the absolute value of the correlation coefficient and not its significance. We chose to consider correlation coefficients between predictors and SLOF scales ≥0.20 as trustworthy.

Since two variables may be connected in a SEM through several pathways, direct effects, indirect effects and total effects were estimated. A direct effect is a relationship between two variables not mediated by any other variable in the model. An indirect effect of one variable on another is a relationship mediated by one or more variables along a specific pathway and is calculated as the product of all the involved direct effects. The total effect is the sum of the direct and all indirect effects.

The model parameters, which provide information about the relationships among the variables, can be interpreted as standardized regression weights, as in linear regression models. Squared multiple correlations (R2) were obtained for each endogenous variable to estimate the amount of variance explained by its predictors. Lastly, the standardized coefficients for indirect effects were examined to evaluate mediation effects. Significant effects suggest mediation is present, and full mediation is indicated by the direct path no longer being significant.

An advantage of SEM is the use of latent variables. This implies using more than one variable to map onto a theoretical construct, thus allowing reduction of the measurement error and a more accurate estimation of the true value of the construct than it would be possible using a single variable.

In the present study, neurocognition, social cognition, resilience and real-life functioning (SLOF) were defined as latent variables. Neurocognition included the MCCB domains “processing speed”, “attention”, “working memory”, “verbal memory”, “visual memory” and “problem solving”; social cognition corresponded to FEIT, TASIT and MSCEIT scores; resilience combined “perception of self”, “perception of the future”, “social competence” and “family cohesion”, and SLOF reflected the five domains of the scale, i.e., “skills in self-care”, “interpersonal relationships”, “social acceptability”, “community activities” and “working abilities”.

For the purpose of the SEM, neurocognition, social cognition and functional capacity variables were standardized with respect to Italian normative data. All the other variables were transformed into z-scores. Disability pension was coded as a dichotomous variable (yes/no). Other incentives, including financial and/or practical support from the family, as well as registration in an unemployment list, were used as a count variable, ranging from 0 to 3.

To define our initial SEM model, we hypothesized relationships between variables consistent with published research. Specifically, we hypothesized that psychopathology (including positive symptoms, disorganization, negative symptoms and depression), neurocognition, extrapyramidal symptoms, incentives, and socio-economic status would predict functioning both directly and indirectly, through the mediation of social cognition and functional capacity. Moreover, we assumed first that SES, resilience, and ISMI would be further mediators of the relationship of predictors with functioning and tested this hypothesis in the model.

The final model was obtained by removing non-significant effects and correlations among predictors lower than 0.20 and testing alternative hypotheses on the relationships among mediators.

Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI, 68), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI, 69) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, 70). TLI and CFI values >0.90 reflect acceptable fit and values >0.95 imply very good fit 71. RMSEA values <0.05 indicate close model fit; values up to 0.08 suggest a reasonable error of approximation in the population, and values >0.10 indicate poor fit 72. The fit indices were assessed collectively, such that a single index that fell just outside the acceptable range was not necessarily considered to reflect poor model fit, provided that the other statistics indicated good model fit. Power analysis was carried out using MacCallum et al's 73 criterion to test the hypothesis of RMSEA's not-close fit. The best-fitting models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, 74). This index has no predefined cut-offs and can only be interpreted when comparing two different models. A lower AIC indicates better model fit.

Analyses were carried out using Stata, version 13.1, and Mplus, version 7.1.

RESULTS

Out of 1691 screened patients, 1180 were eligible; of these, 202 refused to participate, 57 dropped out before completing the procedures and 921 were included in the analyses (641 males, 280 females). Data on demographic and illness-related variables are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Almost all patients were treated with antipsychotics, mostly second-generation drugs, and about one quarter received an integrated treatment, i.e., psychosocial interventions in addition to pharmacotherapy (including cognitive rehabilitation, psychoeducation, social skills training, self-help groups or sheltered employment).

| Gender (% males) | 69.6 |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 40.2±10.7 |

| Married (% yes) | 7.8 |

| Working (% yes) | 29.2 |

| Education (years, mean±SD) | 11.6±3.4 |

| Age at first psychotic episode (years, mean±SD) | 24.0±7.2 |

| Antipsychotic treatment (%) | |

| First generation | 14.2 |

| Second generation | 48.5 |

| Both | 14.1 |

| None | 3.2 |

| Integrated treatment (% yes) | 26.8 |

| Suicide attempts (% yes) | 17.1 |

| Mean±SD | Min/Max | |

|---|---|---|

| PANSS positive | 9.8±4.7 | 4/28 |

| PANSS disorganization | 8.6±3.8 | 3/21 |

| BNSS poor emotional expressivity | 12.8±8.0 | 0/33 |

| BNSS avolition | 20.7±9.6 | 0/45 |

| CDSS (total score) | 4.0±4.0 | 0/21 |

| TMT (total time) | 66.3±46.2 | 15/300 |

| BACS SC (correct responses) | 31.5±13.2 | 0/96 |

| Fluency (number animal names) | 16.5±5.7 | 0/47 |

| CPT-IP (D Prime average) | 1.7±0.8 | −0.39/4.03 |

| WMS-III SS (correct sequences) | 12.3±4.1 | 1/26 |

| LNS (correct responses) | 10.4±4.2 | 0/21 |

| HVLT-R (correct recalls) | 19.0±5.6 | 0/35 |

| BVMT-R (total score) | 16.3±8.8 | 0/36 |

| NAB mazes (total score) | 9.7±6.4 | 0/26 |

| TASIT Sect. 1 (correct items) | 19.7±5.4 | 0/28 |

| TASIT Sect. 2 (correct items) | 36.9±11.7 | 0/60 |

| TASIT Sect. 3 (correct items) | 37.4±12.2 | 0/64 |

| FEIT (correct responses) | 36.8±8.5 | 7/53 |

| MSCEIT (SS-B4) | 78.5±9.0 | 54.6/109.2 |

- PANSS – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, BNSS – Brief Negative Symptom Scale, CDSS – Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, TMT – Trail Making Test - Part A, BACS SC – Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia Symbol Coding, Fluency – Category Fluency, Animal Naming, CPT-IP – Continuous Performance Test, Identical Pairs, WMS-III SS – Wechsler Memory Scale Spatial Span, LNS – Letter-Number Span, HVLT-R – Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised, BVMT-R – Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised, NAB – Neuropsychological Assessment Battery, TASIT – The Awareness of Social Inference Test, FEIT – Facial Emotion Identification Test, MSCEIT – Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, SS-B4 – standard score for the managing emotions branch

Data on personal resources, context-related factors and functional capacity, and SLOF scale scores are provided in Table 3. Overall, study participants showed a modest degree of functional impairment. SLOF domains showing a moderate degree of impairment included interpersonal relationships, community activities and working abilities.

| Personal resources | |

| SES (total score, mean±SD, min/max) | 12.9±7.7, 0/42 |

| Resilience Scale for Adults (mean±SD, min/max) | |

| Perception of self | 18.1±5.5, 0/30 |

| Perception of future | 10.8±4.3, 0/20 |

| Social competence | 18.9±5.3, 6/30 |

| Family cohesion | 20.3±5.7, 3/30 |

| Context-related factors | |

| ISMI (total score, without stigma resistance, mean±SD, min/max) | 2.1±0.5, 1.00/3.92 |

| Number of incentives (%)a | |

| None | 12.7 |

| One | 29.2 |

| Two | 32.9 |

| Three | 18.2 |

| Four | 7.0 |

| Functional capacity and real-life functioning | |

| UPSA-B (total score, mean±SD, min/max) | 67.5±22.3, 0/100 |

| SLOF (mean±SD, min/max) | |

| Physical functioning | 24.2±1.3, 15/25 |

| Skills in self-care | 31.7±4.0, 10/35 |

| Interpersonal relationships | 22.3±6.1, 7/35 |

| Social acceptability | 32.5±3.3, 14/35 |

| Community activities | 45.9±8.6, 11/55 |

| Working abilities | 20.0±6.2, 6/30 |

- SES – Services Engagement Scale, ISMI – Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness, UPSA-B – UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment, SLOF – Specific Levels of Functioning

- a Including financial support from the family, practical support from the family, registered in an unemployment list, disability pension

Inspection of the bivariate correlation matrix revealed that the socio-economic status (Hollingshead index), the social network and extrapyramidal symptoms were unrelated to all mediators and SLOF; therefore, these variables were not used in further analyses.

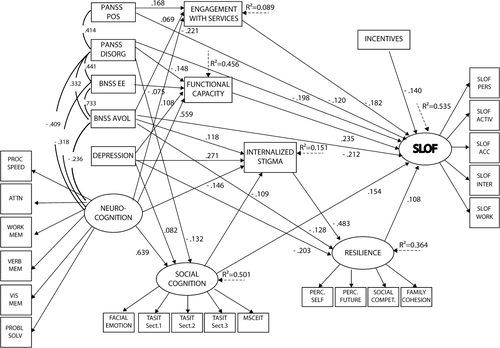

In our first SEM model (Figure 1), PANSS positive, PANSS disorganization, BNSS avolition, BNSS poor emotional expression, depression, neurocognition, and incentives were used as independent predictors; social cognition, functional capacity, internalized stigma, resilience and service engagement were used as mediators, and SLOF was the dependent variable.

Initial structural equation model. Neurocognition, social cognition, resilience and SLOF are latent variables (with arrows pointing to their respective indicators). PANSS POS, PANSS DISORG, BNSS avolition, BNSS-EE, depression, neurocognition and incentives are independent predictors. Social cognition, functional capacity, internalized stigma, resilience and service engagement are mediators, and SLOF is the dependent variable. PANSS – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, POS – positive, DISORG – disorganization, BNSS – Brief Negative Symptom Scale, EE – poor emotional expression, AVOL – avolition, PROC SPEED – processing speed, ATTN – attention, WORK MEM – working memory, VERB MEM – verbal memory, VIS MEM – visuospatial memory, PROBL SOLV – problem solving, TASIT – The Awareness of Social Inference Test, MSCEIT – Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, PERC. SELF – perception of self, PERC. FUTURE – perception of the future, SOCIAL COMPET. – social competence, SLOF – Specific Level of Functioning, PERS – skills in self-care, ACTIV – community activities, ACC – social acceptability, INTER – interpersonal relationships, WORK – working abilities

PANSS positive and PANSS disorganization, as well as BNSS avolition, proved to have significant direct and indirect effects; depression had no significant effect on SLOF, and BNSS poor emotional expression was only indirectly and weakly related with SLOF (Table 4, Figure 1). Neurocognition had only indirect effects on SLOF. Incentives proved to be a significant predictor, and social cognition, functional capacity, resilience, internalized stigma and service engagement served as mediators, as hypothesized.

| Direct | p | Total indirect | p | Total | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional capacity | 0.245 | <0.001 | - | - | 0.245 | <0.001 |

| Social cognition | 0.169 | <0.001 | - | - | 0.169 | <0.001 |

| Internalized stigma | - | - | −0.061 | 0.001 | −0.061 | <0.001 |

| Resilience | 0.116 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.116 | <0.001 |

| Neurocognition | - | - | 0.302 | <0.001 | 0.302 | <0.001 |

| PANSS positive | −0.117 | 0.001 | −0.031 | <0.001 | −0.148 | <0.001 |

| PANSS disorganization | −0.201 | <0.001 | −0.063 | <0.001 | −0.264 | <0.001 |

| BNSS avolition | −0.210 | <0.001 | −0.046 | 0.001 | −0.255 | <0.001 |

| Incentives | −0.142 | <0.001 | - | - | −0.142 | <0.001 |

| Service engagement | −0.184 | <0.001 | - | - | −0.184 | <0.001 |

- SLOF – Specific Levels of Functioning, PANSS – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, BNSS – Brief Negative Symptom Scale

CFI and TLI indices for this model were 0.925 and 0.916, respectively, and the RMSEA index was 0.047, denoting a good fit to the data. The included variables explained 53.5% of SLOF variance.

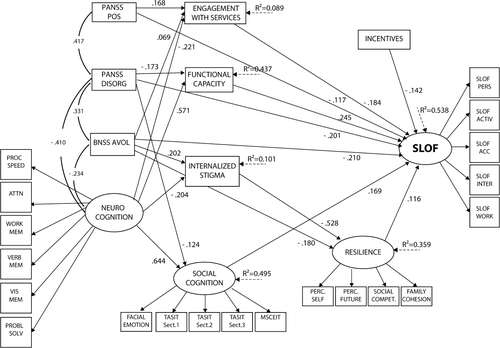

After trimming non-significant paths (from neurocognition, CDSS, BNSS poor emotional expression to SLOF, and from social cognition to internalized stigma), a final model was obtained with five predictors and five mediators (Figure 2). This model accounted for 53.8% of variance of the SLOF, was more parsimonious and proved to have a better fit compared with the initial model (CFI=0.940, TLI=0.932, RMSEA=0.044). Comparison of the AIC indices for the initial and the final model (84686.906 and 80400.015, respectively) further supported the choice of the latter to represent the relationships among variables without loss of information.

Final structural equation model after trimming of non-significant paths. Neurocognition, social cognition, resilience and SLOF are latent variables (with arrows pointing to their respective indicators). PANSS POS, PANSS DISORG, BNSS avolition, neurocognition and incentives are independent predictors. Social cognition, functional capacity, internalized stigma, resilience and service engagement are mediators, and SLOF is the dependent variable. PANSS – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, POS – positive, DISORG – disorganization, BNSS – Brief Negative Symptom Scale, EE – poor emotional expression, AVOL – avolition, PROC SPEED – processing speed, ATTN – attention, WORK MEM – working memory, VERB MEM – verbal memory, VIS MEM – visuospatial memory, PROBL SOLV – problem solving, TASIT – The Awareness of Social Inference Test, MSCEIT – Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, PERC. SELF – perception of self, PERC. FUTURE – perception of the future, SOCIAL COMPET. – social competence, SLOF – Specific Level of Functioning, PERS – skills in self-care, ACTIV – community activities, ACC – social acceptability, INTER – interpersonal relationships, WORK – working abilities

In this final model, PANSS positive, PANSS disorganization and BNSS avolition showed a negative direct effect on SLOF (Table 4), indicating that higher levels of psychopathology are associated with poorer functioning. Several indirect effects on SLOF were also observed: PANSS positive through service engagement, PANSS disorganization through functional capacity, and BNSS avolition through service engagement and resilience. BNSS avolition had also an effect on internalized stigma that, in its turn, was indirectly associated with SLOF through resilience. Neurocognition showed indirect effects on SLOF through four different mediators: service engagement, functional capacity, internalized stigma (through resilience) and social cognition, and when compared with other predictors of the same mediator, it always showed the strongest effect (Figure 2).

Table 4 provides a summary of direct, indirect and total effects on SLOF of variables included in the final model. Neurocognition showed the strongest total effect, followed by disorganization, avolition, functional capacity, service engagement, social cognition, positive symptoms, incentives, resilience and internalized stigma.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study carried out so far on factors associated with real-life functioning in people with schizophrenia, in terms of both sample size and number of investigated domains. According to our findings, variables relevant to the disease, personal resources and social context explain 53.8% of real-life functioning variance in patients with schizophrenia living in the community and treated with antipsychotics, mainly second-generation drugs.

Neurocognition exhibited the strongest association with real-life functioning. This result corroborates previous findings of moderate to large correlations of neurocognition with everyday functioning measures 75-77. Our use of neurocognition as a latent variable, to reduce its measurement error, further supports the robustness of the finding. In line with previous research 77, 78, neurocognition proved to be a distal variable with respect to real-life functioning, since its relationship with SLOF was mediated by functional capacity, social cognition, service engagement and internalized stigma.

Associations between functional capacity and neurocognition have previously been reported in cross-sectional studies 79-81. In our model neurocognition was the strongest predictor of functional capacity, which reflects its important contribution to the latter construct. Actually, both measures assess the individuals' capability of performing tasks and/or behaviors in a standardized setting, but tests of functional capacity do so in more “ecological” way, i.e., simulating everyday life tasks, though not carried out in the community 15, 82. The role of functional capacity as mediator of the impact of neurocognition on real-life functioning reported in our study has also been previously observed 13, 14.

The correlation between social cognition and real-life functioning ranged from small to large in previous studies, mainly depending on the examined aspect of social cognition, with largest effects observed for theory of mind tasks 17, 20. Our findings confirm that social cognition accounts for a unique proportion of functioning variance, independent of neurocognition 83-87, support its independence from negative symptoms 18, 22, and do not support its role as mediator of the impact of negative symptoms on real-life functioning 7.

To our knowledge, the role of service engagement and internalized stigma as mediators between neurocognition and real-life functioning has not been investigated in previous studies. In our model, service engagement was directly associated with SLOF, while internalized stigma showed, in its turn, an indirect association with SLOF, mediated by resilience. Service engagement, as assessed in the present study, reflects subject's degree of collaboration with mental health services (e.g., active participation in defining treatment plans, ability to seek service help if needed and to show up on time for the appointments) and adherence to prescribed treatments. According to our results, impaired cognitive functioning interferes with subject's collaboration to treatment and therefore it is an obstacle to successful outcome.

Internalized stigma, according to a recent meta-analysis including 127 studies, is directly associated with severity of psychiatric symptoms and inversely related to levels of hope, empowerment, self-efficacy, quality of life and adherence to treatment 49. Our data confirm the previously reported association between internalized stigma and negative symptoms 88, and extend this finding to neurocognition. An association between social cognition and internalized stigma has been reported by other authors 89, but has not been observed in our model. A possible interpretation of this discrepancy could be that the relationship between social cognition and internalized stigma is spurious; in other words, it is possible that neurocognitive impairment underlies both these variables and therefore accounts for their relationship.

The illness-related variables disorganization, positive symptoms and avolition were both directly and indirectly related to functioning. The key role of disorganization observed in our study deserves comments. The PANSS items “conceptual disorganization”, “difficulties in abstract thinking” and “poor attention” are generally considered core aspects of the disorganization factor 90-92; in the present study, the structure of the PANSS disorganization dimension was defined according to the consensus 5-factor solution proposed by Wallwork et al 55, in which the three above-mentioned items load on the disorganization factor. The overlap of the items “difficulties in abstract thinking” and “poor attention” with neurocognitive impairment cannot be underestimated. As a matter of fact, in our data, neurocognition and disorganization showed a significant inverse correlation and a similar pattern of association with SLOF, through functional capacity and social cognition.

Avolition had both a direct and an indirect relationship with SLOF. In the indirect path, it has service engagement, resilience and internalized stigma (in its turn associated with SLOF through resilience) as mediators. In the initial model, both BNSS factors had been included, but BNSS poor emotional expression only showed an indirect and weak relation with SLOF, and its exclusion from the final model did not worsen the fit or reduce the explanatory power of the model.

A significant relationship between avolition and poor social outcome has been reported in previous studies 93-95. In a recent investigation on long-term stability and outcome of negative symptoms, Galderisi et al 23 found that avolition has a higher predictive value of functional outcome than poor emotional expression at 5-year follow-up. The scarce relevance of poor emotional expression to real-life functioning is in line with Foussias et al's findings 96.

The strong impact of avolition on real-life functioning might be due to the partial overlap between these two measures. However, the degree of overlap was most probably limited in our study, since avolition, as measured by the BNSS, provides an assessment of both behavioral (e.g., deficit in initiating and persisting in different activities) and inner experience aspects (e.g., lack of interest and motivation in different activities, impaired anticipation of rewarding outcome), while the real-life assessment provided by a caregiver mainly focuses on subject's performance and behavior in several types of everyday activities. Efforts aimed to improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of avolition represent a priority of research in schizophrenia, and the implementation of treatments targeting motivation is likely to be an important tool to enable people with schizophrenia to achieve a meaningful life.

At odds with previous literature 8, 13, 14, 53, 97, 98, no impact of depression on real-life functioning was observed in our study. The discrepancy with previous studies might be due to the use of different instruments for the assessment of depression (mostly the Beck Depression Inventory, a self-report measure, in prior investigations) and the low degree of severity of depression in our sample (mean score=4, with a cutoff of 6/7 for depression in the CDSS).

Extrapyramidal symptoms, family socio-economic status and social network were not included in the SEM, as they showed no or weak associations with SLOF and mediating variables. As to extrapyramidal symptoms, we cannot exclude that the prevalence of treatment with second-generation antipsychotics yielded a floor effect, making their impact on SLOF negligible, while for both social network and socio-economic status we cannot rule out the possibility of redundancy with other variables, or poor performance of the used instruments.

Access to family and social incentives had a negative association with SLOF, i.e., a higher number of incentives was associated with a poorer real-life functioning. Due to the cross-sectional study design, this association may be interpreted either way, i.e., access to incentives may be due to functional impairment or incentives may have a negative impact on real-life functioning. In fact, many patients would not renounce to the disability pension or the support received by the family for a job, as the latter is generally regarded as less stable and more effortful. Directly relevant to this point is the finding by Rosenheck et al 99 that disability compensation status, which is often linked to the individual's health insurance coverage, had the largest negative impact on vocational outcomes of all the measured predictors.

In conclusion, we found that some illness-related variables (neurocognition, disorganization, avolition and positive symptoms) and incentives predict real-life functioning either directly or through the mediation of resilience, stigma, social cognition, functional capacity and engagement with mental health services. The final SEM model explained about 54% of the SLOF variance, a higher percentage compared with those reported in similar studies that used neurocognition, social cognition, social competence and negative symptoms to predict real-life functioning (7-25%) 7, 22, 83, 87.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size and the use of state-of-the-art instruments to assess neurocognitive, psychopathological, social cognition, and personal resources domains. Some possible limitations include the restricted variability range of patients' clinical characteristics and functioning in the real life (most of the patients showed a mild/moderate degree of symptoms severity and functional impairment); the use of SLOF as a latent variable, which might have advantages, but might also prevent the identification of predictors of specific domains, and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow to test causal relationships.

Our findings can have important treatment and research implications. The impact of neurocognition and social cognition on real-life functioning suggests that training addressing neurocognitive and social cognition impairment should be part of integrated treatment packages for schizophrenia. A greater emphasis on social cognition than on neurocognition has been suggested, given the greater proximity and higher direct explanatory power of the former, with respect to the latter domain 100. However, there is no evidence that social cognitive training alone counteracts neurocognitive impairment, whose impact on other domains, i.e., functional capacity and service engagement, would probably persist, in spite of possible improvement in social cognition.

The complexity of the pathway from neurocognition to real-life functioning through internalized stigma suggests that, in order to enhance the impact of interventions targeting neurocognitive impairment on functioning in the real life, we also need to promote reduction of internalized stigma related to mental illness and minimize its negative effects. Data have been provided that anti-stigma interventions are effective at reducing internalized stigma 101-103, but the impact of such positive outcome on other dimensions of the disorder and on patients' functioning does need further investigation.

Our finding that avolition is an independent domain with respect to both neurocognition and social cognition suggests that the search for treatments with an impact on this domain should be a priority of mental health research strategies.

The contribution of resilience to real-life functioning highlights the importance of personalization when designing treatment plans and defining life goals together with our patients. Prejudicial optimistic or, more frequently, pessimistic attitudes should always be modulated by the awareness that individuals do vary a lot in terms of personal resources, and such a variability does not allow undue generalization.

Improved understanding of factors that hinder real-life functioning is vital for treatments to translate into more positive outcomes. Findings from the present study provide a valuable contribution in this direction; in particular, the observed complex associations among investigated predictors, mediators and real-life functioning strongly suggest that integrated and personalized programs should be provided as standard treatment to people with schizophrenia.

Appendix

Members of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses include: Marcello Chieffi, Stefania De Simone, Francesco De Riso, Rosa Giugliano, Giuseppe Piegari, Annarita Vignapiano (University of Naples SUN, Naples); Grazia Caforio, Marina Mancini, Lucia Colagiorgio (University of Bari); Stefano Porcelli, Raffaele Salfi, Oriana Bianchini (University of Bologna); Alessandro Galluzzo, Stefano Barlati (University of Brescia); Bernardo Carpiniello, Francesca Fatteri, Silvia Lostia di Santa Sofia (University of Cagliari); Dario Cannavò, Giuseppe Minutolo, Maria Signorelli (University of Catania); Giovanni Martinotti, Giuseppe Di Iorio, Tiziano Acciavatti (University of Chieti); Stefano Pallanti, Carlo Faravelli (University of Florence); Mario Altamura, Eleonora Stella, Daniele Marasco (University of Foggia); Pietro Calcagno, Matteo Respino, Valentina Marozzi (University of Genoa); Ilaria Riccardi, Alberto Collazzoni, Paolo Stratta, Laura Giusti, Donatella Ussorio, Ida Delauretis (University of L'Aquila); Marta Serati, Alice Caldiroli, Carlotta Palazzo (University of Milan); Felice Iasevoli (University of Naples Federico II); Carla Gramaglia, Sabrina Gili, Eleonora Gattoni (University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara); Elena Tenconi, Valeria Giannunzio, Francesco Monaco (University of Padua); Chiara De Panfilis, Annalisa Camerlengo, Paolo Ossola (University of Parma); Paola Landi, Grazia Rutigliano, Irene Pergentini, Mauro Mauri (University of Pisa); Fabio Di Fabio, Chiara Torti, Antonino Buzzanca, Anna Comparelli, Antonella De Carolis, Valentina Corigliano (Sapienza University of Rome); Giorgio Di Lorenzo, Cinzia Niolu, Alfonso Troisi (Tor Vergata University of Rome); Giulio Corrivetti, Gaetano Pinto, Ferdinando Diasco (Department of Mental Health, Salerno); Arianna Goracci, Simone Bolognesi, Elisa Borghini (University of Siena); Cristiana Montemagni, Tiziana Frieri, Nadia Birindelli (University of Turin).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, the Italian Society of Psychopathology (SOPSI), the Italian Society of Biological Psychiatry (SIPB), Roche, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck and Bristol-Myers Squibb.