Psychological symptoms and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in China: A multicenter study

Jixiang Zhang, Chuan Liu, Ping An, Min Chen, Yuping Wei, Jinting Li and Suqi Zeng have contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Aims

To investigate the current situation of mental psychology and quality of life (QoL) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in China, and analyze the influencing factors.

Methods

A unified questionnaire was developed to collect clinical data on IBD patients from 42 hospitals in 22 provinces from September 2021 to May 2022. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis was conducted, and independent influencing factors were screened out to construct nomogram. The consistency index (C-index), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, area under the ROC curve (AUC), calibration curve, and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to evaluate the discrimination, accuracy, and clinical utility of the nomogram model.

Results

A total of 2478 IBD patients were surveyed, including 1371 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 1107 patients with Crohn's disease (CD). Among them, 25.5%, 29.7%, 60.2%, and 37.7% of IBD patients had anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance and poor QoL, respectively. The proportion of anxiety, depression, and poor QoL in UC patients was significantly higher than that in CD patients (all p < 0.05), but there was no difference in sleep disturbance between them (p = 0.737). Female, higher disease activity and the first visit were independent risk factors for anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance in IBD patients (all p < 0.05). The first visit, higher disease activity, abdominal pain and diarrhea symptoms, anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance were independent risk factors for the poor QoL of patients (all p < 0.05). The AUC value of the nomogram prediction model for predicting poor QoL was 0.773 (95% CI: 0.754–0.792). The calibration diagram of the model showed that the calibration curve fit well with the ideal curve, and DCA showed that the nomogram model could bring clinical benefits.

Conclusion

IBD patients have higher anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, which affect their QoL. The nomogram prediction model we constructed has high accuracy and performance when predicting QoL.

Graphical Abstract

Key Summary

Summarize the established knowledge on this subject

-

Concomitant psychological problems are independent predictors of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptom severity, which not only negatively affect patients' quality of life (QoL), but also increase healthcare utilization and caregiver burden.

-

There are no large sample epidemiological survey data on the mental state and QoL of IBD patients in China.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

-

This study is the first multi-center large sample survey on the mental state and QoL of IBD patients, which truly reflects the current status of psychological symptoms, sleep quality and QoL of IBD patients in China.

-

IBD patients have higher anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, which affect their QoL.

-

Nomogram models with high accuracy and performance were constructed to predict psychological symptoms, sleep quality and QoL in IBD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic immune-mediated intestinal mucosal disease, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD), and its prevalence and incidence are increasing worldwide.1-3 The disease burden of IBD is a challenge for patients, not only when it comes to the physical manifestations of the disease, but also the additional psychological and social burden,4 as patients often have psychological comorbidities like anxiety and depression.5 A large amount of evidence shows that IBD patients are more likely to suffer from psychological problems, such as anxiety or depression, than the general population,6, 7 and the prevalence fluctuates in different countries.8 A recent systematic review9 showed that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in IBD patients was 32.1%, and the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 25.2%. These concomitant psychological problems are independent predictors of the severity of IBD symptoms, not only negatively affecting patients' quality of life (QoL), but also increasing healthcare utilization and caregiver burden.10-14 Therefore, the mental state of IBD patients has been given more attention.

Understanding the epidemiology of psychological comorbidities in IBD patients is very important for both treatment providers for IBD and payers, as it has a direct impact on healthcare utilization.14 At the same time, it is also vital to clarify the influencing factors of these combined psychological problems and determine effective intervention measures for the mental health of patients and the clinical work of medical staff. Screening people with IBD for psychological disorders have recently been shown to have mental health benefits.15 Patient questionnaires are readily available and can be used to diagnose anxiety and depression.16 Currently, there are no large sample epidemiological survey data on the mental state and QoL of IBD patients in China. Although there are local relevant data in other countries,8, 9 the sample size is not large enough. Through a national multicenter cross-sectional survey, this study aims to obtain the current status of mental psychology and QoL of IBD patients in China and its influencing factors, and to provide a basis for the timely diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in IBD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population

This is a national multicenter cross-sectional survey on the mental state and QoL of IBD patients in China, conducted by the Psychology Club of IBD Group of Gastroenterology Society of the Chinese Medical Association and the Chinese Association for Mental Hygiene from September 2021 to May 2022. This study is divided into three stages: observation, training, and investigation. In the observation stage, well-known psychological experts from the Chinese Association for Mental Hygiene went to many IBD centers for investigation, observing the process of diagnosis and treatment of patients by nurses and doctors and formed an observation report. According to the observation results, a survey meeting was held to form the standard language and the final draft of the survey questionnaire. In the training stage, the standard techniques for inquiry and treatment were provided to the investigators (doctors from 42 IBD centers) based on the information obtained from the observation stage by psychological experts. The investigators were also trained to use the questionnaire platform system. In the research stage, the investigators conducted research on IBD patients through an information platform. The questionnaire is in an electronic form and can be logged in by scanning the two-dimensional code. 66 gastroenterologists from 42 hospitals in 22 provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the Central Government) participated in the survey, and a total of 2478 valid questionnaires were collected.

Inclusion criteria: (1) All patients with IBD were diagnosed by doctors according to the Chinese Consensus on Diagnosis and Treatment in IBD (2018, Beijing)17; (2) Age ≥18 years old; (3) Patients who can understand and agree to be investigated (e.g., willing to accept the doctor's management and psychological investigation, obey the management of medication compliance, etc.); (4) Complete clinical data. Exclusion criteria: (1) Pregnant or lactating women; (2) Lack of reading and writing skills and communication difficulties; (3) Combined with other diseases that seriously affect the QoL and/or mental state of patients (other intestinal diseases, malignant tumors, etc.) or history of mental illness or previous/current treatment for mental illness (medication/psychotherapy, etc.). The screening flow chart of the patients is shown in Figure S1. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University.

Study assessments and data collection

General data collection

Collect and sort out different gender general clinical characteristics of IBD patients, including age, weight, the first visit, disease activity, disease course, main clinical manifestations (diarrhea, abdominal pain, hematochezia, parenteral, complications, etc.), drugs (5-aminosalicylic acid, glucocorticoid and immunosuppressants, biological agents, and traditional Chinese medicine), and surgery. Disease activity was determined according to the Chinese Consensus on Diagnosis and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (2018, Beijing).17 For example, the modified Mayo score and CDAI score were used to assess the disease activity of UC and CD, respectively. Modified Mayo score and CDAI score are currently the most commonly used clinical indicators to evaluate disease activity and efficacy. The modified Mayo score: <2 is considered in remission, 3–5 is mild activity, 6–10 is moderate activity, and 11–12 is severe activity; the CDAI score: <150 is clinical remission, 150–220 is mild activity, 221–450 is moderate activity, and >450 is severe activity. Diarrhea is usually defined as three or more bowel movements per day with stools that appear liquid or semi-liquid at the time of defecation. Abdominal pain is usually a sensation of discomfort, vague pain, or tingling in the abdomen that the patient feels. The first visit is defined as the patient's first visit to the hospital, that is, the patient comes to the hospital for professional diagnosis and treatment for the first time.

Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale and patient health questionnaire-9

Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) and patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are two widely used self-report screening tools for anxiety and depression. Both scales instruct participants to indicate how often they have been bothered by each symptom over the last 2 weeks using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). Possible scores on the PHQ-9 ranged from 0 to 27, and on the GAD-7 from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression and anxiety. Scores of 10 or higher are typically used to indicate probable diagnostic status on each of these measures.18-20 Therefore, 10 points were taken as the cut-off point in this study. The score ranges for anxiety and depressive symptom severity in both GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were as follows: minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–15), and severe (15+) symptoms.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality during the last 1 month, which is a well-validated self-assessment method. There are 7 dimensions in this scale, and the total score is between 0 and 21, with scores >5 indicating significant sleep disturbance.21 A score of 0–5 indicates good sleep quality, 6–10 indicates medium sleep quality, 11–15 indicates poor sleep quality, and 16–21 indicates very poor sleep quality.

Inflammatory bowel disease quality-of-life questionnaire

Inflammatory bowel disease quality-of-life questionnaire (IBD-Q) has been widely used to evaluate the QoL of IBD patients in the past 2 weeks, including 4 dimensions of bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional ability, and social ability, with a total of 32 items. Each item was divided into 7 grades, with 1–7 points, and the total score ranged from 32 to 224. The higher the total score, the better the QoL of patients, with scores <169 indicative of a poor QoL.18, 22

Statistical analysis

Excel 2021 was used to input and sort out the survey data, and the SPSS 26.0 and R 4.1.0 software was used for statistical analysis of the data. Count data were expressed as frequency and percentage, and a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for comparison between groups. The odds ratio (OR) ratio was considered significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) does not include 1. Measurement data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation ( ± s), and a comparison between the two groups was performed by a t-test. Indicators with p < 0.05 were further included in Logistic multivariate regression analysis, and independent influencing factors were screened out to construct the nomogram prediction models. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn, and the prediction ability of the model was evaluated by the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The Bootstrap method was used to resample the model 1000 times for internal verification. The consistency index (C-index) was used to evaluate the discrimination of the nomogram prediction model, and the calibration curve was drawn to evaluate the model calibration. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical utility. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of IBD patients

Two thousand four hundred and seventy eight IBD patients were enrolled, including 1371 UC patients (55.3%) and 1107 CD patients (44.7%), as shown in Table 1. The average age of IBD patients was 38.0 years, and the number of males (62.4%) was greater than that of females. 61.8% of IBD patients were in the disease's active stage, most of which were mild or moderate. 57.3%, 61.2%, and 42.7% of the patients had abdominal pain, diarrhea and hematochezia, respectively. At the same time, 8.0% of the patients had parenteral manifestations, and 8.3% of the patients had complications. 61.8%, 15.5%, 14.5%, 51.4%, 3.7%, and 12.3% of patients received 5-aminosalicylic acid, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, biological agents, Chinese Herbs, and surgery, respectively. There were significant differences in the above clinical characteristics between UC patients and CD patients (all p < 0.05).

| Characteristics | IBD (n = 2478) | UC (n = 1371) | CD (n = 1107) | Statistical value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old, ± s) | 37.96 ± 12.54 | 41.64 ± 12.59 | 33.40 ± 10.88 | 17.468a | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg, ± s) | 61.51 ± 11.76 | 62.57 ± 11.81 | 60.19 ± 11.57 | 5.039a | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | 72.291 | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 1547 (62.4) | 754 (55.0) | 793 (71.6) | ||

| Female | 931 (37.6) | 617 (45.0) | 314 (28.4) | ||

| First visit, n (%) | 50.543 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 493 (19.9) | 343 (25.0) | 150 (13.6) | ||

| No | 1985 (80.1) | 1028 (75.0) | 957 (86.4) | ||

| Disease activity, n (%) | 98.610 | <0.001 | |||

| Remission | 946 (38.2) | 404 (29.5) | 542 (49.0) | ||

| Active | 1532 (61.8) | 967 (70.5) | 565 (51.0) | 0.287 | 0.866 |

| Mild | 588 (38.4) | 369 (38.2) | 219 (38.8) | ||

| Moderate | 734 (47.9) | 462 (47.8) | 272 (48.1) | ||

| Severe | 210 (13.7) | 136 (14.1) | 74 (13.1) | ||

| Disease duration, n (%) | 35.219 | <0.001 | |||

| <2 years | 939 (37.9) | 583 (42.6) | 356 (32.2) | ||

| 2–5 years | 764 (30.9) | 365 (26.7) | 399 (36.0) | ||

| >5 years | 773 (31.2) | 421 (30.8) | 352 (31.8) | ||

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 52.884 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1517 (61.2) | 927 (67.6) | 590 (53.3) | ||

| No | 961 (38.8) | 444 (32.4) | 517 (46.7) | ||

| Hematochezia, n (%) | 514.415 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1058 (42.7) | 863 (62.9) | 195 (17.6) | ||

| No | 1420 (57.3) | 508 (37.1) | 912 (82.4) | ||

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 51.770 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1419 (57.3) | 697 (50.8) | 722 (65.2) | ||

| No | 1059 (42.7) | 674 (49.2) | 385 (34.8) | ||

| Extraintestinal manifestation, n (%) | 4.076 | 0.044 | |||

| Yes | 198 (8.0) | 96 (7.0) | 102 (9.2) | ||

| No | 2280 (92.0) | 1275 (93.0) | 1005 (90.8) | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 142.636 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 205 (8.3) | 32 (2.3) | 173 (15.6) | ||

| No | 2273 (91.7) | 1339 (97.7) | 934 (84.4) | ||

| 5-Aminosalicylic acid, n (%) | 890.945 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 947 (38.2) | 165 (12.0) | 782 (70.6) | ||

| Yes | 1531 (61.8) | 1206 (88.0) | 325 (29.4) | ||

| Mesalamine | 1512 (61.0) | 1192 (86.9) | 320 (28.9) | 867.292 | <0.001 |

| Sulfasalazine | 66 (2.7) | 59 (4.3) | 7 (0.6) | 31.839 | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 33.914 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2095 (84.5) | 1107 (80.7) | 988 (89.3) | ||

| Yes | 383 (15.5) | 264 (19.3) | 119 (10.7) | ||

| Prednisone | 235 (9.5) | 142 (10.4) | 93 (8.4) | 2.731 | 0.098 |

| Methylprednisolone | 46 (1.9) | 36 (2.6) | 10 (0.9) | 9.974 | 0.002 |

| Dexamethasone | 31 (1.3) | 29 (2.1) | 2 (0.2) | 18.555 | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 162.524 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2118 (85.5) | 1283 (93.6) | 835 (75.4) | ||

| Yes | 360 (14.5) | 88 (6.4) | 272 (24.6) | ||

| Thiopurines | 320 (12.9) | 61 (4.4) | 259 (23.4) | 195.514 | <0.001 |

| Methotrexate | 25 (1.0) | 15 (1.1) | 10 (0.9) | 0.223 | 0.637 |

| Biological agents, n (%) | 691.674 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1205 (48.6) | 992 (72.4) | 213 (19.2) | ||

| Yes | 1273 (51.4) | 379 (27.6) | 894 (80.8) | ||

| Infliximab | 854 (34.5) | 200 (14.6) | 654 (59.1) | 536.761 | <0.001 |

| Vedolizumab | 254 (10.3) | 153 (11.2) | 101 (9.1) | 2.760 | 0.097 |

| Adalimumab | 103 (4.2) | 27 (2.0) | 76 (6.9) | 36.853 | <0.001 |

| Ustekinumab | 69 (2.8) | 3 (0.2) | 66 (6.0) | 74.630 | <0.001 |

| Chinese herbs, n (%) | 69.823 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2386 (96.3) | 1281 (93.4) | 1105 (99.8) | ||

| Yes | 92 (3.7) | 90 (6.6) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Surgery, n (%) | 324.222 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2174 (87.7) | 1349 (98.4) | 825 (74.5) | ||

| Yes | 304 (12.3) | 22 (1.6) | 282 (25.5) | 25.853 | <0.001 |

| Small bowel surgery | 128 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 128 (11.5) | ||

| Colon surgery | 66 (2.7) | 13 (1.0) | 53 (4.8) | ||

| Rectal or anal surgery | 83 (3.3) | 6 (0.4) | 77 (7.0) | ||

| Others | 27 (1.1) | 3 (0.2) | 24 (2.2) | ||

| Surgery timeframe | 3.183 | 0.364 | |||

| <2 years | 95 (3.8) | 7 (0.5) | 88 (7.9) | ||

| 2–5 years | 85 (3.4) | 8 (0.6) | 77 (7.0) | ||

| 5–10 years | 49 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | 48 (4.3) | ||

| >10 years | 16 (0.6) | 2 (0.1) | 14 (1.3) |

- Abbreviations: CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

- a Refers to t value, others refer to χ2 value; the above drugs only show the commonly used drugs, and there may be overlapping use between different drugs.

Psychological symptoms, sleep quality and quality of life in IBD patients

Scores of psychological symptoms, sleep quality and quality of life related scales in IBD patients

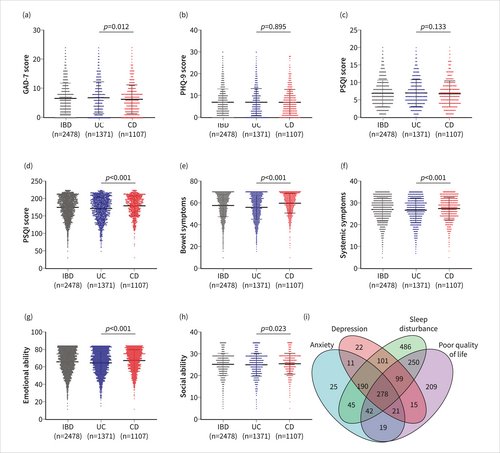

The GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PSQI scores of UC patients were slightly higher than those of CD patients, and the IBD-Q score of UC patients was significantly lower than that of CD patients (p < 0.001), indicating that the mental state and QoL of UC patients were worse than those of CD patients, as shown in Figure 1a–h and Table S1.

Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale score (a), patient health questionnaire-9 score (b), Pittsburgh sleep quality index score (c), IBD-Q score (d) and Venn diagram (i) of IBD patients, IBD-Q score including 4 dimensions of bowel symptoms (e), systemic symptoms (f), emotional ability (g), and social ability (h). CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-Q, inflammatory bowel disease quality-of-life questionnaire; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Psychological symptoms, sleep quality and quality of life in IBD patients

The results showed that 25.5%, 29.7%, 60.2%, and 37.7% of IBD patients had anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL, respectively, as shown in Table 2. Among them, 278 IBD patients (11.2%) had anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL (Figure 1i). The proportion of anxiety, depression, and poor QoL in UC patients was higher than that in CD patients (all p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in sleep quality between the two groups (p = 0.737). Meanwhile, we analyzed the clinical characteristics of IBD patients with anxiety or depression or coexisting anxiety and depression, as shown in Table S2. In addition, we analyzed the prevalence of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL in IBD, UC, and CD according to different classifications, such as gender, age, disease duration, disease activity, and severity (Figure S2–S4).

| IBD (n = 2478) | UC (n = 1371) | CD (n = 1107) | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 13.687 | <0.001 | |||

| No (GAD-7<10) | 1847 (74.5) | 982 (71.6) | 865 (78.1) | ||

| Yes (GAD-7≥10) | 631 (25.5) | 389 (28.4) | 242 (21.9) | ||

| Symptom severity | 17.277 | 0.001 | |||

| Minimal | 976 (39.4) | 539 (39.3) | 437 (39.5) | ||

| Mild | 871 (35.1) | 443 (32.3) | 428 (38.7) | ||

| Moderate | 397 (16.0) | 246 (17.9) | 151 (13.6) | ||

| Severe | 234 (9.4) | 143 (10.4) | 91 (8.2) | ||

| Depression | 3.865 | 0.049 | |||

| No (PHQ-9<10) | 1741 (70.3) | 941 (68.6) | 800 (72.3) | ||

| Yes (PHQ-9≥10) | 737 (29.7) | 430 (31.4) | 307 (27.7) | ||

| Symptom severity | 12.883 | 0.005 | |||

| Minimal | 1032 (41.6) | 588 (42.9) | 444 (40.1) | ||

| Mild | 709 (28.6) | 353 (25.7) | 356 (32.2) | ||

| Moderate | 422 (17.0) | 243 (17.7) | 179 (16.2) | ||

| Severe | 315 (12.7) | 187 (13.6) | 128 (11.6) | ||

| Sleep disturbance | 0.113 | 0.737 | |||

| No (PSQI≤5) | 987 (39.8) | 542 (39.5) | 445 (40.2) | ||

| Yes (PSQI>5) | 1491 (60.2) | 829 (60.5) | 662 (59.8) | ||

| Sleep quality | 5.382 | 0.146 | |||

| Good | 987 (39.8) | 542 (39.5) | 445 (40.2) | ||

| Medium | 1073 (43.3) | 579 (42.2) | 494 (44.6) | ||

| Poor | 353 (14.2) | 215 (15.7) | 138 (12.5) | ||

| Very poor | 65 (2.6) | 35 (2.6) | 30 (2.7) | ||

| Quality of life | 26.564 | <0.001 | |||

| Not poor (IBD-Q≥169) | 1545 (62.3) | 793 (57.8) | 752 (67.9) | ||

| Poor (IBD-Q<169) | 933 (37.7) | 578 (42.2) | 355 (32.1) | ||

| IBD-Q score range | 26.899 | <0.001 | |||

| 177–224 | 1355 (54.7) | 702 (51.2) | 653 (59.0) | ||

| 129–176 | 920 (37.1) | 526 (38.4) | 394 (35.6) | ||

| 81–128 | 191 (7.7) | 135 (9.8) | 56 (5.1) | ||

| 32–80 | 12 (0.5) | 8 (0.6) | 4 (0.4) |

- Abbreviations: CD, Crohn's disease; GAD-7, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-Q, inflammatory bowel disease quality-of-life questionnaire; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Influencing factors of psychological symptoms, sleep quality, and quality of life in IBD patients

Univariate analysis of influencing factors of psychological symptoms, sleep quality, and quality of life in IBD patients

Gender, first visit, disease activity, and hematochezia symptoms were statistically significant in anxiety, depression, sleep quality, and QoL of IBD patients (all p < 0.05). The use of different drugs (5-aminosalicylic acid, immunosuppressants, and biological agents) and surgical treatment could affect the anxiety of patients (all p < 0.05), and diarrhea, and abdominal pain symptoms could affect the depression of patients (all p < 0.05). The disease course, abdominal pain, diarrhea symptoms, use of biological agents and surgical treatment could all affect the QoL of patients (all p < 0.05). In addition, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL affected each other (See Table S3). IBD patients were divided into UC and CD groups, and univariate analyses were performed, respectively, as shown in Table S4 and Table S5.

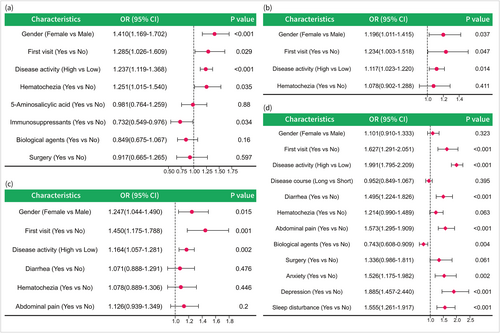

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of influencing factors of psychological symptoms, sleep quality, and quality of life in IBD patients

Female, high disease activity, and the first visit were independent risk factors for anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance in IBD patients (all p < 0.05). The disappearance of hematochezia symptoms and the use of immunosuppressants could alleviate the anxiety of patients (all p < 0.05). At the first visit, high disease activity, abdominal pain and diarrhea symptoms, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance were independent risk factors for patients' QoL, and the use of biological agents can improve the QoL of patients (all p < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2 and Table S6. Similarly, IBD patients were divided into UC and CD groups and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, respectively, as shown in Table S7 and Table S8.

Forest plots of independent influencing factors of anxiety (a), sleep disturbance (b), depression (c), and poor quality of life (d) in IBD patients. CD, Crohn's disease; CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; OR, odds ratio; UC, ulcerative colitis.

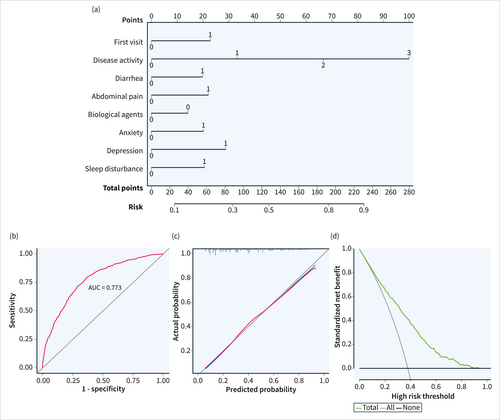

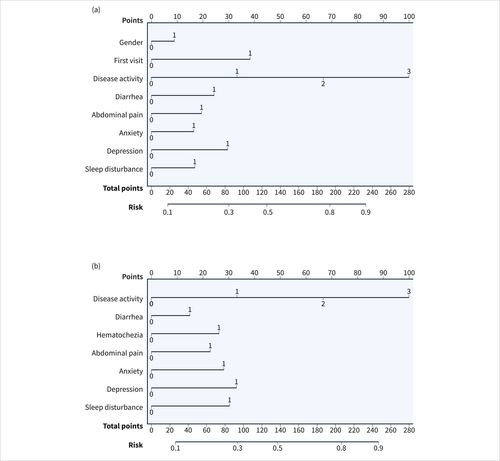

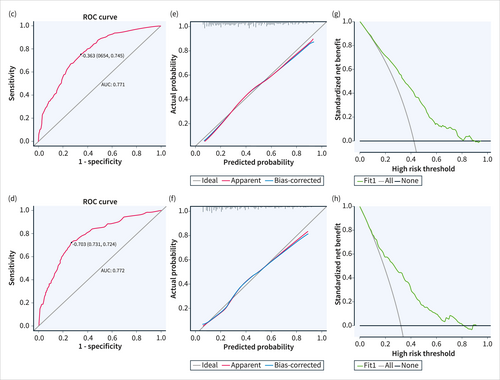

Construction and verification of the nomogram for predicting anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor quality of life in IBD patients

Based on the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis, four nomogram models were constructed to predict the risks of anxiety (Figure S5A), depression (Figure S5B), sleep disturbance (Figure S5C), and poor QoL (Figure 3a) in IBD patients. The ROC curves were used to analyze the predictive ability of the nomogram prediction models, and the AUC values of the models for predicting anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL were 0.614 (95% CI: 0.588–0.639) (Figure S5D), 0.580 (95% CI: 0.555–0.604) (Figure S5E), 0.550 (95% CI: 0.528–0.573) (Figure S5F), and 0.773 (95% CI: 0.754–0.792) (Figure 3b), respectively, indicating that the predicted values were acceptable. The Bootstrap method was used to repeatedly sample 1000 times to verify the modeling effect of the nomogram. The C index of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL prediction models were 0.608, 0.576, 0.547, and 0.768, respectively, indicating that the discrimination of the model was acceptable. The calibration diagrams of the four models showed that the calibration curves fit well with the ideal curve (Figure 3c, Figure S5G-I), indicating that the accuracy of the models was high. DCA (Figure 3d, Figure S5J-L) showed that the clinical benefit of the nomogram models based on risk factors was significantly higher than that of the models without risk factors, especially the nomogram for predicting poor QoL (Figure 3d). In addition, IBD patients were classified into UC and CD, and the prediction models were constructed and validated, respectively, as shown in Figure 4 and Figures S6, S7.

Establishment of a nomogram model for predicting poor quality of life (a) in IBD patients, and internal validation and evaluation of the nomogram model (the ROC curve [b], calibration curve [c] and decision curve [d] for poor quality of life). (Disease activity: 0 = Remission, 1 = Mild active, 2 = Moderate active, 3 = Severe active; Other variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic).

Establishment of nomogram models for predicting poor quality of life (a: UC; b: CD) in IBD patients, and internal validation and evaluation of nomogram models (the ROC curves [c: UC; d: CD], calibration curves [e: UC; f: CD] and decision curves [g: UC; h: CD] for poor quality of life). (Disease activity: 0 = Remission, 1 = Mild active, 2 = Moderate active, 3 = Severe active; Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Other variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes; CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; UC, ulcerative colitis).

Establishment of nomogram models for predicting poor quality of life (a: UC; b: CD) in IBD patients, and internal validation and evaluation of nomogram models (the ROC curves [c: UC; d: CD], calibration curves [e: UC; f: CD] and decision curves [g: UC; h: CD] for poor quality of life). (Disease activity: 0 = Remission, 1 = Mild active, 2 = Moderate active, 3 = Severe active; Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Other variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes; CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; UC, ulcerative colitis).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, the prevalence of IBD has been increasing worldwide and is projected to reach 1% by 2030, creating a significant global burden.2, 23 The study showed that the proportion of mental disorders in IBD patients was 7.69%, which was significantly higher than that in non-IBD people.24 There is a mutual influence on the mental and physical health of IBD patients,25 and this psychological burden not only increases the physical burden of the disease but is also related to direct and indirect costs.11-14 Therefore, it is very important to identify and intervene in the psychological abnormalities of IBD patients.

It was reported26 that in the past 12 years, the peak age of UC diagnosis changed from 55 to 59 years old to 20–24 years old, while the peak age of CD changed from 19 years old to 17 years old, and males accounted for the majority of both CD and UC, which was consistent with this study and both showed a gradual younger incidence. A descriptive study27 showed that the most common gastrointestinal symptoms in adult IBD patients were abdominal pain (63.9%) and diarrhea (62.3%), which were basically consistent with this study (57.3% and 61.2%, respectively). At present, the treatment of IBD is mainly drug therapy, including aminosalicylate, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, and biological agents,28, 29 which has also been shown in this study, and 5-aminosalicylic acid is the basic drug used by most IBD people.30

This survey showed that the proportion of IBD patients with anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and poor QoL was 25.5%, 29.7%, 60.2% and 37.7%, respectively. A systematic review9 of 77 studies involving 30,118 patients showed that the incidence of anxiety and depression in IBD patients was 32.1% and 25.2%, respectively, which was slightly different from that of this study. This may be due to different scoring scale criteria and different regional populations,6, 8 but is nevertheless significantly higher than the non-IBD population,7 which should still be paid attention to. The study31 reported that the proportion of poor sleep quality in active and inactive IBD patients was 76.71% and 48.84%, respectively, and the research32 concluded that the proportion of sleep disturbances in IBD patients was 67.5%, which was basically consistent with the results of this survey. Hence, IBD patients need to take relevant measures to improve sleep quality. A Dutch study33 showed that the average IBD-Q score of the patients was 182.17, while the average of this study was 175.82. The difference between the two was not significant, but the difference may be due to the better medical conditions in developed countries, such as effective remote assistance and home treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.33 Therefore, we should provide patients with more social support in daily life, which is helpful in improving patients happiness.34 The Venn diagram revealed that 11.2% of IBD patients had concomitant anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and poor QoL, indicating a significant overlap and interrelation within this subgroup, possibly due to a combination of multiple factors. Firstly, the chronic inflammation and worsening symptoms inherent to IBD may contribute to increased physical and psychological burden, leading to the development of anxiety and depression.35 Secondly, sleep disturbances may result from disease-related pain, abdominal discomfort, and frequent nocturnal bowel movements. The compounded effects of these psychophysical factors can mutually influence each other, ultimately resulting in a decline in QoL.

This study showed that the incidence of UC is higher than CD in China, which is consistent with most Asian countries,36 such as Japan and Korea. Similarly, an American study37 also showed a higher incidence of UC than CD. Our findings also showed a higher prevalence of anxiety-depression and poorer QoL in patients with UC compared with CD, which is consistent with the trend of some studies,38, 39 but inconsistent with the results of many studies in other countries.40-44 In the studies by Caplan et al.39 and Ganguli et al.,38 the results obtained showed a higher QoL in the group of patients with CD, although none of these studies showed statistically significant differences between groups. However, among Western countries, a UK study40 showed a higher prevalence of anxiety-depression in CD than in UC, and a systematic review in Spain41 showed a higher prevalence of anxiety-depression in CD than in UC among adults. A study from Korea,41 despite being an Asian country, showed a higher prevalence of anxiety-depression in CD than in UC, although there was no statistical difference. Meanwhile, a Spanish study43 showed that QoL was worse in CD than in UC, and a Brazilian study44 also showed that QoL scores were lower in UC than in CD. This difference may be due to multiple factors.36 On the one hand, this may be due to the fact that the UC patients in this study were older, more female, and mostly active compared to the CD patients. On the other hand, this may be due to a combination of genetic factors, environmental factors, differences in medical practice and diagnostic criteria, and cultural and social factors.35, 45, 46 Further research could provide insight into the relationship between these factors to better understand the variability of IBD globally and provide targeted support and interventions to improve patients' QoL and mental health.

Consistent with this study, a series of studies47-50 have shown that females and patients with active disease are more likely to suffer from anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Compared to their male counterparts, female patients may have more emotional problems influenced by factors such as physical and psychological endurance.51 Consequently, female patients should receive more psychological support.52 Higher PSQI scores48 were associated with female gender, implying that women have worse sleep quality. Previous studies have emphasized that anxiety and depression are higher in active diseases than in inactive diseases, and QoL scores seem to be lower,50, 53 so disease activity has a significant impact on the mental health of patients. In particular, patients in the active stage are more likely to suffer from psychological problems and sleep disturbance,49 leading to a decline in their QoL,18, 54 which may be due to the increased level of circulating inflammatory mediators in IBD patients in the active stage.55 Additionally, patients who visit the clinic for the first time might initially find it difficult to accept the occurrence of the disease, resulting in a heavy psychological burden, affecting their QoL. Research56 has shown that abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating were associated with depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance, and even during remission, gastrointestinal symptoms were the main factors that influence QoL in IBD patients, which might be due to brain-gut interaction.57 In addition, it is well known that mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance can lead to poorer QoL.32, 58

Mental health issues have long been a prominent area of concern in IBD patients. Previous research has shown a close association between anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and poor QoL with the onset and clinical course of IBD.9, 47-50 However, up to this point, there have been no predictive models that fully meet the specific needs of IBD patients. The innovation of this study lies in the construction of four distinct nomogram models, each addressing different aspects, and subjecting them to comprehensive performance evaluations. This research bridges an existing gap in the literature by providing a comprehensive predictive tool for addressing the psychological well-being of IBD patients, offering promising clinical applications. These nomogram models provide a robust reference point for the clinical management and intervention of IBD patients. They enable healthcare professionals to better identify high-risk patients and take timely measures to improve their QoL. It's worth noting that while these nomogram models exhibit superior performance in predicting a decline in the QoL, they still hold significant value in predicting anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances since these psychological health issues are closely intertwined with the overall QoL for IBD patients. In summary, this study offers a feasible predictive tool for addressing the mental health issues of IBD patients and underscores the significance of psychological well-being in the treatment and management of IBD. Future research can further enhance these nomogram models to improve their predictive capabilities and explore additional intervention measures. Furthermore, there is a need for more in-depth research to elucidate the etiological mechanisms behind the psychological health issues in IBD patients, allowing for a better understanding and intervention strategies.

The mechanism of psychological problems in IBD patients may involve inflammation, intestinal microecology, and brain-gut axis.4, 55, 57, 59, 60 The surge of inflammatory cytokines in the body and their effect on the brain is suggested as a plausible explanation for the increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders,55 as inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of mood disorders.4 The study59 demonstrated associations of psychological outcome parameters including anxiety, depression, and perceived stress with differences in mucosa-associated microbiota diversity and abundance in IBD patients since the gut microbiome has been linked to mood, stress, anxiety, and depression.61 The brain-gut axis provides the physiological link between the CNS and gastrointestinal tract that might facilitate these relationships.57 Psycho-neuro-endocrine-immune modulation through the brain-gut axis likely plays a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD.60 Psychoneuroimmune modulation may be the platform that serves to interface the human experience, the state of mind, the gut microbiome, and the immune response that ultimately drives the phenotypic expression of IBD, which to date has been the focus of IBD therapy.60 Although the number of studies examining the relationship between IBD and psycho-psychological abnormalities has increased substantially in recent years, there is still a distinct lack of research into the causes of the increase in psychological disorders in IBD. It is possible that the psychological impact of the gastrointestinal symptoms could be sufficient to induce depression or anxiety. However, the inflammatory mediators themselves may also lead to changes in mood or anxiety.4

This study is the first multi-center large sample survey on the mental state and QoL of IBD patients carried out by the Psychology Club of IBD Group of Gastroenterology Society of the Chinese Medical Association and the Chinese Association for Mental Hygiene,52 and it truly reflects the current status of psychological symptoms, sleep quality and QoL of IBD patients in China. The survey results can help medical staff to early identify high-risk groups of IBD patients who may have psychological abnormalities, and carry out timely intervention and disease monitoring, which is of great significance for the long-term treatment and health management of IBD patients. However, this paper also has limitations inherent in cross-sectional studies, such as unrecorded confounders and the inability to infer causality for the described associations. The lack of a healthy control is also a major limitation of the present study. Due to the limitations of the survey and the way the data were collected, we are unable to provide complete information on disease classification, such as the analysis of the Montreal classification. Furthermore, this study can only reflect the psycho-psychological status of IBD patients in a recent period of time, but it cannot reflect their dynamic changes. Given that this study was performed within the COVID-19 pandemic, it might have interfered with the psychological aspects of the patients. In addition, the nomogram prediction model in this study has not been verified externally, so its applicability needs to be verified in a larger data range.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, IBD patients have higher anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, which affect the QoL of patients. In addition, we constructed a nomogram prediction model with high accuracy and performance to predict poor QoL in IBD patients. In the clinical diagnosis and treatment of IBD patients, we should actively identify whether patients have psychological abnormalities and their severity, and provide effective health education and intervention measures in a timely manner according to the specific conditions of patients, so as to improve the mental health and QoL of IBD patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

(I) Conception and design: Jixiang Zhang, Chuan Liu, Ping An, Min Chen, Kaichun Wu, Weiguo Dong; (II) Administrative support: Weiguo Dong, Kaichun Wu; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Jixiang Zhang, Chuan Liu, Ping An, Min Chen, Kaichun Wu, Weiguo Dong; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Jixiang Zhang, Chuan Liu, Ping An, Min Chen, Dan Xiang, Yanhui Cai, Jun Li, Baili Chen, Liqian Cui, Jiaming Qian, Zhongchun Liu, Changqing Jiang, Jie Shi, Kaichun Wu, Weiguo Dong; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Jixiang Zhang, Chuan Liu, Ping An, Min Chen, Suqi Zeng, Yuping Wei, Jinting Li; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All author.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank 42 participating institutions and associated IBD physicians for their help in this study, listed below (in no particular order): Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Hong Lyv), the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University (Fenrong Chen, Sumei Sha), Peking University First Hospital (Tian Yuling), Peking University Third Hospital (Jun Li), Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (Ye Zong, Haiying Zhao), Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (Tianyu Zhang), First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Baili Chen, Ren Mao, Yao He, Shenghong Zhang), General Hospital, Tianjin Medical University (Hailong Cao, Shuai Su, Wenyao Dong, Lili Yang), Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Qian Liu, Rongrong Zhan), Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Jing Liu), the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Xiangrong Chen, Xiaowei Chen, Lingyan Shi), the Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Ningbo University (Jinfeng Wen), Jiangsu Province Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Jingjing Ma), Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Lei Zhu), General Hospital of Eastern Theater Command of Chinese People's Liberation Army (Juan Wei), the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Han Xu), Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (Nan Nan, Feng Tian), the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Xiuli Chen, Jingwei Mao), Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Liangru Zhu), Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (Mei Ye), Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Shuijiao Chen), the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Hanyu Wang), Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (Xue Yang, Yinghui Zhang), the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Juan Wu), Qilu Hospital, Shandong University (Xiaoqing Jia), the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Xueli Ding, Jing Guo, Ailing Liu), the First Hospital of Jilin University (Haibo Sun, Jing Zhan), the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (Yating Qi), General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University (Shaoqi Yang, Ting Ye), the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Sumin Wang, Dandan Wang), the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Xiaoping Lyu, Junhua Fan, Shiquan Li), Chongqing General Hospital (Chongqing Hospital, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences) (Lingya Xiang), the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (Ping Yao, Hongliang Gao), the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Wanying Li), the First Affiliated Hospital of the University of Science and Technology of China, Anhui Provincial Hospital (Xuemei Xu), Daping Hospital, Army Medical University (Zhuqing Qiu), Affiliated Hangzhou First People's Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Wen Lyu), the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University (Xiaolin Zhong), General Hospital of Southern Theater Command of People's Liberation Army (Ang Li, Xiangqiang Liu, Yanchun Ma), Suzhou Municipal Hospital (North District), Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Suzhou Hospital (Zhi Pang). In addition, the authors would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82170549) funded this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. The clinical research Ethics Review approval number of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University was WDRY2022-K150.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.