High vaccination coverage and infection rate result in a robust SARS-CoV-2-specific immunity in the majority of liver cirrhosis and transplant patients: A single-center cross-sectional study

J. Schulze Zur Wiesch and M. Sterneck contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Background

In the third year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, little is known about the vaccine- and infection-induced immune response in liver transplant recipients (LTR) and liver cirrhosis patients (LCP).

Objective

This cross-sectional study assessed the vaccination coverage, infection rate, and the resulting humoral and cellular SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses in a cohort of LTR and LCP at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany between March and May 2023.

Methods

Clinical and laboratory data from 244 consecutive patients (160 LTR and 84 LCP) were collected via chart review and a patient survey. Immune responses were determined via standard spike(S)- and nucleocapsid-protein serology and a spike-specific Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

Results

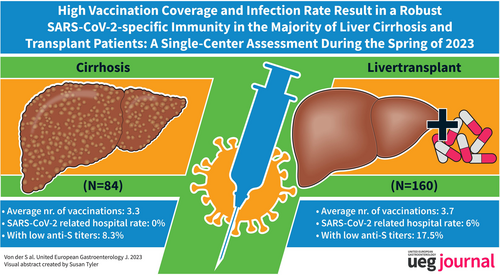

On average, LTR and LCP were vaccinated 3.7 and 3.3 times, respectively and 59.4% of patients received ≥4 vaccinations. Altogether, 68.1% (109/160) of LTR and 70.2% (59/84) of LCP experienced a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Most infections occurred during the Omicron wave in 2022 after an average of 3.0 vaccinations. Overall, the hospitalization rate was low (<6%) in both groups. An average of 4.3 antigen contacts by vaccination and/or infection resulted in a seroconversion rate of 98.4%. However, 17.5% (28/160) of LTR and 8.3% (7/84) of LCP demonstrated only low anti-S titers (<1000 AU/ml), and 24.6% (16/65) of LTR and 20.4% (10/59) of LCP had negative or low IGRA responses. Patients with hybrid immunity (vaccination plus infection) elicited significantly higher anti-S titers compared with uninfected patients with the same number of spike antigen contacts. A total of 22.2% of patients refused additional booster vaccinations.

Conclusion

By spring 2023, high vaccination coverage and infection rate have resulted in a robust, mostly hybrid, humoral and cellular immune response in most LTR and LCP. However, booster vaccinations with vaccines covering new variants seem advisable, especially in patients with low immune responses and risk factors for severe disease.

Graphical Abstract

Key summary

Summarizing the established knowledge on this subject

-

Vaccination is an important tool to protect vulnerable liver transplant recipients (LTR) and liver cirrhosis patients (LCP) from severe COVID-19.

-

Little is known about the real-world situation encompassing vaccination coverage, infection rate and the subsequent hybrid immunity in LTR and LCP in the third year of the pandemic.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

-

Vaccination coverage in LTR and LCP was high, and approximately 60% of patients received ≥4 vaccinations.

-

The infection rate was high, reaching 68% and 70% in LTR and LCP, respectively, with a low hospitalization rate of <6%.

-

An average of 4.3 spike antigen exposures, by vaccination and/or infection, resulted in a seroconversion rate of 98.4%.

-

However, there were still low anti-S RBD titers detectable in 14.3% of patients and an insufficient cellular response in 22.8% of patients.

INTRODUCTION

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies reported high mortality rates among liver transplant recipients (LTR) and liver cirrhosis patients (LCP).1-3 Additionally, in both patient groups, multiple studies showed a decreased immune response after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2,4-8 especially in those LTR and LCP who were particularly vulnerable to severe COVID-19 courses due to their advanced age and the presence of multiple comorbidities.5, 6, 9 Additional vaccine doses were shown to augment the immune response and increase seroconversion rates, leading to the general practice of administering multiple booster doses to these patients.4, 10 It has been estimated that vaccination reduces the risk of mortality by up to 100-fold in LTR.11 Recently, studies in healthy controls (HC) have shown that the humoral and cellular immune response is particularly robust in case of vaccination plus breakthrough infection – termed hybrid immunity.12-15 However, similar data are largely missing for immunosuppressed patients.

Thus, 3 years after the beginning of this pandemic, there is scant knowledge of the overall level of immune protection of these vulnerable patient populations. It is not known to what extent adequate SARS-CoV-2-specific immune protection exists and whether further booster vaccinations should be recommended. Therefore, this large single-center study aimed to assess the current real-world situation regarding vaccination and infection status as well as the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in a cohort of LTR and LCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adult LTR and LCP who visited the outpatient clinic of University Hospital Hamburg, Germany, between February 28th, and 12 May 2023, were prospectively included in the study. After obtaining written informed consent, participants were requested to complete a questionnaire, and blood samples were collected. Clinical data and patient characteristics were obtained from electronic medical records. As a reference point for robust humoral and cellular immune response levels, we used uninfected healthy controls (HC) from our database of previous studies who had been vaccinated three times.4

Epidemiologic data on the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections and vaccination status of the general population in Hamburg, Germany, were obtained from the COVID-19 Data Hub of the Robert Koch Institute.16, 17 This study was approved by the local ethics committee of Hamburg, Germany (Reg. numbers PV7103 and PV7298, 28/01/2021).

Assessment of the SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular spike-specific immune response

The humoral immune response was determined by quantifying the spike-specific antibody (anti-S) levels against the receptor-binding domain (RBD) with the Roche Elecsys SARS-CoV-2 S assay in arbitrary units (AU) per ml with a linear range from 0,4 AU/mL to 25,000 AU/mL as previously described.6, 15 SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (NC) antibodies were assessed by the Elecsys anti-NC-SARS-CoV-2 Ig assay (Roche, Mannheim Germany; cut-off ≥1 COI/mL). The spike antigen T-cell response was determined by a commercial spike-specific Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA, EUROIMMUN) and quantified according to the manufacturer's instructions with values >100 mIU/ml interpreted as low positive and values >200 mIU/ml as high-positive as previously described.4, 6, 10, 18

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including median and interquartile range (IQR) or average (range) for continuous variables or the number of patients and percentages for categorical variables were used to present epidemiological data. SPSS statistics version 27 (IBM Corp) was used for statistical analysis, including significance tests according to the respective questions (Pearson's chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, Mann-Whitney U Test, or Kruskal-Wallis test). Binary logistic regression was performed to assess predictive factors for future vaccination denial, anti-S RBD <1000 and ≥10,000 AU/ml, and anti-NC antibody negativity after COVID-19. Prism GraphPad Version 8.0.1 for Windows (Graph-Pad Software) was used to create graphs and figures.

RESULTS

Current COVID-19 vaccination status and attitude toward further vaccinations

Altogether, 244 consecutive patients (160 LTR and 84 LCP) were included in this study. Clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of LCP (n = 51, 60.7%) had decompensated Child–Pugh B or C cirrhosis. Most LTR were long-term recipients (median time since liver transplantation: 7 (IQR 3–15.8) years) and 121 (75.6%) had received their graft before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

| LTR | LCP | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 160 | n = 84 | ||

| n (%)/Median (IQR) | n (%)/Median (IQR) | ||

| Age [years] | 56 (44–65) | 57.5 (47–63) | 0.527 |

| Females | 69 (43.1) | 34 (40.5) | 0.691 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 24.4 (22–27.6) | 27.4 (23.3–31.2) | <0.001 |

| (n = 81) | |||

| Time since LT [years] | 7 (3–15.8) | - | |

| LT after 02–2020 | 39 (24.4) | ||

| Etiology of liver disease | |||

| ALD | 22 (13.8) | 35 (41.7) | |

| NASH | 7 (4.4) | 16 (19) | |

| AILD | 45 (28.1) | 14 (16.7) | |

| Viral | 24 (15) | 5 (6) | |

| Pediatric | 9 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Genetic | 18 (11.3) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Other | 35 (21.9) | 12 (14.3) | |

| HCC | 23 (14.4) | 6 (7.1) | |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diabetes | 37 (23.1) | 29 (34.5) | 0.057 |

| Arterial hypertension | 91 (56.9) | 28 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Age >60 years | 63 (39.4) | 37 (44) | 0.481 |

| eGFR <45 mL/min | 54 (33.8) | 11 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 18 (11.3) | 24 (29.6) (n = 81) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 risk factors | 36 (22.5) | 21 (25) | 0.661 |

| CCI | 5 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 0.145 |

| Immunosuppression | |||

| Monotherapy | 42 (26.3) | ||

| Tacrolimus | 32 (20) | ||

| Cyclosporine | 6 (3.8) | ||

| mTORi | 3 (1.9) | ||

| MMF | 1 (0.6) | ||

| AZA | 3 (3.6) | ||

| Prednisone | 1 (1.2) | ||

| CNI + MMF | 38 (23.8) | ||

| CNI + AZA | 3 (1.9) | ||

| CNI + mTORi | 16 (10) | ||

| CNI + prednisone | 21 (13.1) | ||

| mTORi + MMF | 1 (0.6) | ||

| mTORi + AZA | 0 (0) | ||

| mTORi + prednisone | 4 (2.5) | ||

| AZA + prednisone | - | 2 (2.4) | |

| ≥3 Immunosuppressants | 35 (21.9) | ||

| Child-pugh-score | |||

| Child-pugh class A | - | 33 (39.3) | |

| Child-pugh class B | - | 33 (39.3) | |

| Child-pugh class C | - | 18 (21.4) | |

| MELD-score | - | 12 (9.3–15) (n = 80) | |

| TIPS | - | 19 (22.6) | |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Leucocytes [Mrd/l] | 6 (4.6–7.5) | 5.3 (3.8–6.6) | 0.021 |

| Lymphocytes [Mrd/l] | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) (n = 82) | 0.063 |

| eGFR [ml/min] | 55 (39.2–80) | 83.5 (62.5–102) | <0.001 |

- Note: Baseline characteristics of all study participants. Frequencies and percentages are given for nominal and ordinal variables. For numerical variables median and interquartile range were calculated. If no “n” value is given, data were available for all study participants. Statistical analysis was performed with Pearson's chi-squared Test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant and highlighted in bold.

- Abbreviations: AILD, Autoimmune liver disease; ALD, Alcoholic liver disease; AZA, Azathioprine; BMI, Body Mass Index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CNI, Calcineurin inhibitors; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IQR, Interquartile range; LCP, liver cirrhosis patients; LT, liver transplantation; LTR, liver transplant recipients; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; mTORi, mTOR inhibitor; NASH, Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

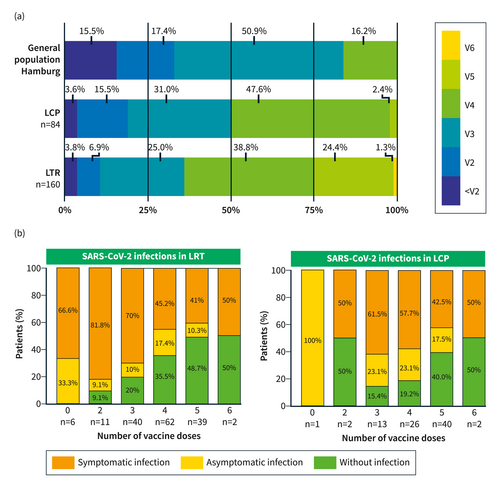

On average, LTR were vaccinated 3.7 (range: 0–6) and LCP 3.3 (range: 0–5) times. Fewer than 5% (9/244) of individuals had not received primary immunization defined as at least two vaccine doses (Figure 1a). On the other hand, 89.4% of LTR and 81% of LCP received ≥3 vaccine doses and 64.4% of LTR and 50% of LCP received ≥4 vaccine doses, compared to only 16.2% of the general population.16 Altogether, LTR received the highest number of vaccinations, and 25.6% (41/160) of LTR had received five or six vaccine doses. In both patient groups, the median time interval since the last vaccination was approximately one year (LTR: 342 (IQR 163–448.5) days; LCP: 352 (IQR 237–440) days). Twenty-four (15%) LTR received at least one SARS-CoV-2 vaccination before transplantation.

(a) Vaccination status in LCP, LTR, and the general population of Hamburg (age >18 years, in 06–2023). The Data concerning the general population of Hamburg was obtained from the COVID-19 Data Hub of the Robert Koch Institute; <V2: less than 2 vaccinations, V2: 2 vaccinations, V3: 3 vaccinations, V4: 4 vaccinations (the group of V4 in the general population of Hamburg contains all individuals ≥4 vaccinations), V5: 5 vaccinations, V6: 6 vaccinations; (b) Percentage of infections in LTR and LCP in relation to the total number of administered vaccine doses.

The attitude towards further vaccinations was available for 92.2% of patients (n = 225; 147 LTR and 78 LCP). The majority of patients, but more LTR (83%) than LCP (67.9%) agreed to receive additional SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations if recommended by their physician, but 17% of LTR and 32.1% of LCP (p = 0.01) would refuse additional doses in the future. A univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to assess factors associated with the refusal of further SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations (Table 2). Patients opposed to future booster doses had received fewer vaccinations in the past and were more likely to not have received yearly vaccinations against influenza. In the multivariate analysis, having received ≤3 vaccinations was an independent factor for unwillingness to receive further vaccinations (OR 5.924 (2.608–13.455)).

| Agreed/neutral to further vaccinations n = 175 (n; %) | Declined further vaccinations n = 50 (n; %) | p-value univariate | p-value multivariate (n = 209) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously had COVID-19 | 90 (51.4) | 27 (54) | 0.748 | ||

| ≤3 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses | 53 (30.3) | 38 (76) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5.924 (2.608-13.455) |

| Age [years] | 56 (44–64) | 56 (45.5–64) | 0.816 | ||

| Female sex | 66 (37.7) | 25 (50) | 0.119 | ||

| LCP | 53 (30.3) | 25 (50) | 0.010 | 0.075 | 1.961 (0.934–4.118) |

| CCI >5 | 56 (32) | 14 (28) | 0.590 | ||

| No yearly influenza vaccination (n = 209) | 43 (26.2) n = 164 | 23 (51.1) n = 45 | 0.001 | 0.613 | 1.228 (0.554–2.722) |

- Note: Comparison of patients who were neutral towards or agreed with further vaccinations and patients who declined further vaccinations. Frequencies and percentages are given for nominal and ordinal variables. For numerical variables median and interquartile range were calculated. If no “n” value is shown, data were available for all study participants. Statistical analysis was performed with Pearson's chi-squared Test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant and highlighted in bold. A multivariate binomial logistic regression analysis was performed including clinically and statistically relevant predictor variables.

- Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; LCP, liver cirrhosis patients; LTR, liver transplant recipients.

SARS-CoV-2 infection status

From March 2020 until March 2023, 85/160 (53.1%) LTR and 42/84 (50%) LCP had a history of confirmed COVID-19 with positive PCR or antigen test results and typical symptoms. Of 85 infected LTRs, 14.1% (12/85) developed COVID-19 before transplantation and only 6.9% (11/160) of LTRs and 3.6% (3/84) of LCP were infected prior to vaccination. In addition, 24 (15%) LTR and 17 (20.2%) LCP were found to have anti-NC antibodies, as an indication of a previous asymptomatic infection. This resulted in an overall infection rate of 68.1% (109/160) and 70.2% (59/84) in LTR and LCP, respectively. Moreover, 11 (6.9%) LTR and 3 (3.6%) LCP had already suffered from two or more SARS-CoV-2 infections. Thus, LTR and LCP had on average 4.5 (range: 1–8) and 4.0 (range: 1–6) spike antigen exposures, respectively (Suppl. Figure S1).

Figure 1b depicts the frequency of past SARS-CoV-2 infections in relation to the total number of vaccine doses administered. All patients who refused vaccination (100%, n = 7) were infected in the meantime, as well as 84.2% (48/57) of LTR and 81% (34/42) of LCP who received ≤3 vaccinations. On average, LTR and LCP had been vaccinated 3.1 and 2.8 times, respectively, before developing a breakthrough infection.

In line with the epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate of the general population in Northern Germany, only a few COVID-19 cases occurred up to the end of the third pandemic wave in June 2021 (7.6% in LTR, 5.7% in LCP, and 10.1% in the general population).17 Most LTR and LCP developed COVID-19 during the Omicron wave in 2022.19 However, infections occurred slightly later in LTR and LCP than in the local population (Suppl. Figure S2). By the end of June 2022, around 76% of all infections until May 2023 had occurred in the general population of Hamburg, but only 40.9% and 42.9% of all infections in LTR and LCP, respectively.

In total, 16/109 (14.7%) LTR and 1/59 (1.7%) LCP reported having been hospitalized during their SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, only 6 (5.5%) LTR and no LCP required hospitalization due to COVID-19-related complications (Suppl. Table S1). The remaining 10 LTR and 1 LCP (Suppl. Table S2) were hospitalized for either unrelated medical reasons (n = 2), surveillance (n = 2), or for SARS-CoV-2-specific treatment (n = 7). Among the LTR requiring hospitalization, a high number of comorbidities was observed (Charlson comorbidity index 7 (IQR 5.6–7.3)); arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 45 mL/min in 100%, 50%, and 50%, respectively) and 83% were 60 years or older. Overall, 43.5% (37/85) of LTR and 35.7% (15/42) of LCP reported persisting symptoms for more than 4 weeks, defining osCOV-19.20 The most common symptoms were fatigue (57.7%), concentration problems (32.7%), shortness of breath (30.8%), cough (28.8%), loss of smell/taste (26.9%), and headaches (23.1%). Additionally, 16.5% (14/85) of LTR and 19% (8/42) of LCP reported that the symptoms persisted for >12 weeks.

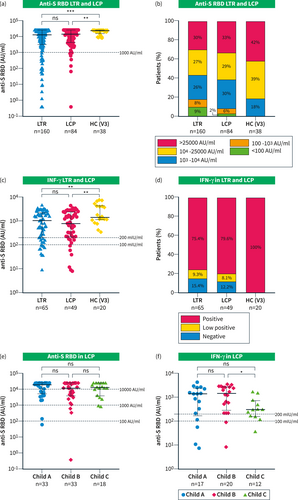

Humoral and cellular immune status

The majority of LTR and LCP had a detectable and robust immune response (Figure 2). The median anti-S RBD titers were quite high and comparable between LTR and LCP after an average of 4.5 (range: 1–8) and 4 spike (range: 1–6) antigen encounters with medians of 12,357 (IQR 3068–25000) AU/ml and 13,957 (IQR 4273–25000) AU/mL, respectively (p = 0.301, Figure 2a). However, in comparison, in our historical cohort of uninfected HC after a median of 3 weeks after the third vaccination, the median anti-S RBD titer was significantly higher with 22,692 (IQR 14566–25000) AU/mL (p = 0.002).4 Only 3 LTR (1.9%) and 1 LCP (1.2%) were found to be seronegative after an average of 4 and 1 antigen exposures, respectively. Also, a low anti-S RBD titer (<1000 AU/mL) was found in 28 (17.5%) LTR and 7 (8.3%) LCP (p = 0.052) after an average of 3.6 (range: 1–6) and 2.5 (range: 1–4) spike antigen contacts, respectively (Figure 2b). Factors associated with low titers - as revealed by a multivariate analysis - were ≤3 vaccinations, no previous infection, eGFR <45 mL/min, and serum IgG levels <6.5 g/L (Suppl. Table S3). On the other hand, a high titer of anti-S RBD antibodies (>10,000 AU/mL) was observed in 56.9% of LTR and 61.9% of LCP after an average of 4.9 (range: 3–8) and 4.3 (range: 2–6) antigen exposures, respectively. Additional multivariate analysis revealed that high anti-S RBD levels were associated with ≥4 vaccinations (OR 4.5; p < 0.001), a previous infection (OR 6.8; p < 0.001), and a higher total serum IgG (OR 1.1; p < 0.001) (Table 3). On the other hand, an interval of >180 days to the last antigen contact was not significantly different in the multivariate analysis and there was no significant difference concerning the type of immunosuppressive treatment. Also, there was no difference between the mean anti-S RBD titers between patients with different Child–Pugh classes (Figure 2e). Of note, the average number of vaccinations (Child A: 3.4, Child B: 3.2, Child C: 3.3) and the infection rates (Child A: 84.8%, Child B: 60.6%, Child C: 61.1%) did not differ between patients with different Child–Pugh classes.

(a–d) Humoral and cellular immune response in all LTR and LCP versus previously assessed HC three weeks after third vaccination from our database; (a) Scattergram presenting individual anti-S RBD levels of LTR, LCP, and HC; (b) Percentages of anti-S RBD titers in LTR and LCP and HC between <100, 100–1000, 1000–10000, 10,000–25000, and >25,000 AU/mL; (c) Scattergram with individual IFN-γ levels in LTR, LCP, and HC; (d) Percentages of LTR, LCP, and HC with a negative (<100 mlU/mL), low positive (100–200 mlU/mL); and high positive (>200 mlU/mL) spike-specific T-cell response as measured by IFN-γ release; (e-f) Immune response in LCP divided by Child-Pugh-Class A, B, and C; (e) Scattergram presenting individual anti-S RBD levels; (f) Scattergram with individual IFN-γ levels; Statistical analysis was performed by Mann–Whitney U test (a, C, E, F), ns and * represent a p-value >0.05 and ≤0.05, respectively.

| Characteristics | Anti-S RBD ≥10,000 AU/mL n = 143 | Anti-S RBD <10,000 AU/mL n = 101 | p-Value univariate | p-Value multivariaten = 219 | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)/median (IQR) | n (%)/median (IQR) | ||||

| Age [years] | 56 (45–86) | 57 (41.5–65) | 0.945 | ||

| Females | 62 (43.4) | 41 (40.6) | 0.667 | ||

| LT during basic vaccination | 9 (6.3) | 7 (6.9) | 0.939 | ||

| LTR at time of inclusion | 91 (63.6) | 69 (68.3) | 0.449 | ||

| ≥4 SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations | 95 (66.4) | 50 (49.5) | 0.008 | <0.001 | 4.537 (2.147-9.586) |

| Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection | 116 (81.1) | 52 (51.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 6.752 (3.233-14.102) |

| Time since last antigen contact >180 days | 61 (42.6) | 67 (68.4) | <0.001 | 0.432 | 1.312 (0.667–2.597) |

| (n = 143) | (n = 98) | ||||

| Risk factors | |||||

| Diabetes | 39 (27.3) | 28 (27.7) | 0.938 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 69 (48.3) | 51 (50.5) | 0.730 | ||

| Age >60 years | 57 (39.9) | 45 (44.6) | 0.464 | ||

| eGFR <45 mL/min | 37 (25.9) | 28 (27.7) | 0.748 | ||

| BMI >30 kg/m2 | 23 (16.1) | 20 (20.4) | 0.447 | ||

| (n = 237) | 26 (18.6) | 13 (13) | 0.249 | ||

| ≥3 risk factors (n = 240) | 43 (30.1) | 34 (33.7) | 0.552 | ||

| CCI >5 | |||||

| Immunosuppression in LTR (n = 160) | (n = 91) | (n = 69) | |||

| Monotherapy | 28 (30.8) | 13 (18.8) | 0.087 | ||

| ≥3 | 18 (19.8) | 17 (24.6) | 0.462 | ||

| Immunosuppressants | 30 (33) | 28 (40.6) | 0.321 | ||

| MMF | 29 (31.9) | 27 (39.1) | 0.340 | ||

| CNI + MMF | 21 (23.1) | 13 (18.8) | 0.517 | ||

| mTORi | 29 (31.9) | 29 (40) | 0.186 | ||

| prednisone | |||||

| Laboratory values | |||||

| Leucocytes <3.8 Mrd/l | 19 (13.3) | 18 (17.8) | 0.331 | ||

| Lymphocytes <1.07 | 50 (35.5) | 45 (45) | 0.125 | ||

| Mrd/l (n = 241) | (n = 141) | (n = 100) | |||

| IgG (g/L) (n = 219) | 13.6 (11.3–17.3) | 11.6 (8.7–14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.138 (1.063-1.220) |

- Note: Comparison of patients with anti-S RBD ≥10,000 AU/ml and <10,000 AU/ml. Frequencies and percentages are given for nominal and ordinal variables. For numerical variables median and interquartile range were calculated. If no “n” value is shown, data were available for all study participants. Statistical analysis was performed with Pearson's chi-squared Test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant and highlighted in bold. A multivariate binomial logistic regression analysis was performed including clinically and statistically relevant predictor variables.

- Abbreviations: Anti-S RBD, anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain; BMI, Body Mass Index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CNI, Calcineurin inhibitors; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; LT, Liver transplantation; LTR, liver transplant recipients; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; mTORi, mTOR inhibitor.

In a subset of patients (65 LTR and 49 LCP), the spike antigen-specific T-cell response was determined by a spike-specific IGRA. The median spike-specific IFN-γ expression upon stimulation was similar in both patient cohorts (1011 and 790 mIU/mL, p = 0.745, Figure 2c). No or only a very weak T-cell response was detectable in 24.6% of LTR and 20.4% LCP (Figure 2d) after an average of 4.6 and 3.4 antigen contacts, respectively. LCP with a Child–Pugh class C showed a lower median IFN-γ response than LCP with Child–Pugh A and B (Child A and B vs. C: 1421 vs. 317.4 mIU/mL, p = 0.034, Figure 2f).

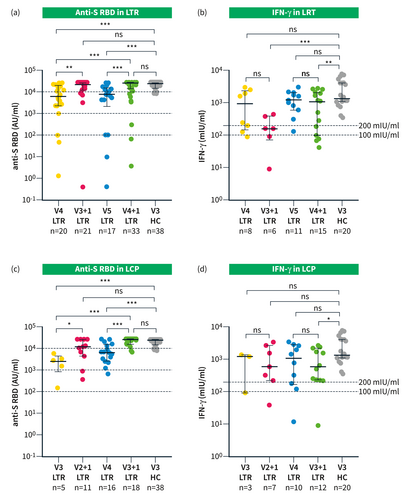

To understand the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infections compared with additional vaccinations on the patients´ overall immune response, we compared the anti-S RBD titers and IGRA results of patients with an equal number of antigen exposures, that is, 4 or 5 vaccinations (V4, V5) versus 3 or 4 vaccinations plus one infection (V3+I, V4+I) in LTR and 3 or 4 vaccinations (V3, V4) versus 2 or 3 vaccinations plus one infection (V2+I and V3+I) in LCP. In both LTR and LCP, median anti-S RBD titers were significantly higher in patients who had a previous infection (LTR: V4 vs. V3+I 5954 vs. 21,127 AU/mL, p = 0.015; V5 vs. V4+I 7345 vs. 22,898 AU/mL, p = 0.007; LCP: V3 vs. V2+I 2500 vs. 11,497 AU/mL, p = 0.034; V4 vs. V3+I 6265 vs. 25,000 AU/mL, p < 0.001; Figures 3a and 3c). In contrast to the humoral response, there was no significant difference between the level of IFN-γ production in LTR and LCP with an equal number of antigen contacts with or without a previous infection (LTR: V4 vs. V3+I 945.4 vs. 160.7 mIU/ml, p = 0.181; V5 vs. V4+I 1220 vs. 1124 mIU/mL, p = 0.474; LCP: V3 vs. V2+I 1230 vs. 596.3 mIU/mL, p = 0.833; V4 vs. V3+I 1112 vs. 573.6 mIU/ml, p = 0.674; Figures 3b,d). There was no difference between LTR and LCP when matched for the number of vaccinations and infections regarding the median antibody titer and IFN-γ expression (Suppl. Figures S3A,B).

(a, b) Immune response in LTR after 4 (V4) and 5 (V5) vaccinations and after 3 and 4 vaccinations plus infection (V3+I and V4+I); (c, d) Immune response in LCP after 3 (V3) and 4 (V4) vaccinations and after 2 vaccinations and 3 vaccinations plus infection (V2+I and V3+I); (a–d) Immune response in previously assessed HC 3 weeks after the third vaccination from our database; (a) Scattergram presenting individual anti-S RBD level in LTR and HC. Median time since the last immunological event (vaccination or infection): V4: 293 (IQR 149.8 d-383.8) days; V3+I: 277 (IQR 147.5–363) days; V5: 133 (IQR 100d-190) days; V4+I 148.5 (IQR 101.3–197.3) days; (b) Scattergram with individual IFN-γ levels in LTR and HC; (c) Scattergram presenting individual anti-S RBD level in LCP and HC. Median time since the last immunological event: V3: 458 (IQR 375–481) days; V2+I: 365 (IQR 257–596) days; V4: 226 (IQR 155.8d-343.8) days; V3+I 238 (IQR130.3–411.8) days; (d) Scattergram with IFN-γ levels in LCP and HC; Statistical analysis was performed by Mann–Whitney U test (a, B, C, D); ns, *, ** and *** represent a p-value >0.05, ≤0.05, <0.01, and <0.001, respectively.

Overall, 22% (28/127) of patients with confirmed previous COVID-19 lacked anti-NC antibody levels above the cut-off level (LTR vs. LCP: 28.2% vs. 9.5%, p = 0.017) after a median of 247 (IQR 131–356) days after the infection. A comparison between patients with and without anti-NC antibodies is shown in Table 4. In the multivariate analysis, anti S-RBD titer <1000 AU/mL and eGFR <45 mL/min were independent factors predicting negative anti-NC antibodies (OR: 2.9 and 6.9, respectively). There was no difference between the anti-NC positive and negative groups with respect to the time interval between antibody determination and infection, age, or other risk factors for a low immune response.

| Characteristics | NC negative patients | NC positive patients | p-value | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 28 | n = 99 | univariate | multivariate | ||

| n (%)/median (IQR) | n (%)/median (IQR) | (n = 127) | (n = 114) | ||

| LTR | 24 (85.7) | 61 (61.6) | 0.017 | ||

| Age [years] | 53 (42.5–62) | 54 (39–63) | 0.911 | ||

| Females | 17 (60.7) | 48 (48.5) | 0.253 | ||

| BMI (n = 125) | 24.49 (21.54–26.83) (n = 28) | 24.86 (21.96–28.46) (n = 97) | 0.792 | ||

| Risk factors | |||||

| Diabetes | 5 (17.9) | 29 (29.3) | 0.334 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 15 (53.6) | 40 (40.4) | 0.214 | ||

| Age >60 years | 7 (25) | 33 (33.3) | 0.402 | ||

| eGFR <45 mL/min | 12 (42.9) | 17 (17.2) | 0.009 | 0.050 | 2.932 (0.998-8.614) |

| ≥3 risk factors | 4 (14.3) | 19 (19.2) | 0.782 | ||

| CCI >5 | 5 (17.9) | 25 (25.3) | 0.614 | ||

| Time since infection [days] | 244.5 (99–341) | 248 (133–357) | 0.558 | ||

| Anti-S RBD <1000 AU/mL | 7 (25) | 5 (5.1) | 0.005 | 0.008 | 6.894 (1.671-28.443) |

| Laboratory values | |||||

| Leucocytes <3.8 | 6 (21.4) | 14 (14.1) | 0.350 | ||

| Mrd/l | 11 (40.7) | 39 (39.4) | 0.899 | ||

| Lymphocytes <1.07 | (n = 27) | (n = 99) | |||

| Mrd/l (n = 126) | 3 (12) | 1 (1.1) | 0.033 | 0.239 | |

| IgG <6.5 g/L (n = 114) | (n = 25) | (n = 89) | 4.928 (0.346–70.09) | ||

- Note: Comparison of all patients with and without nucleocapsid antibodies with previous COVID-19. Frequencies and percentages are given for nominal and ordinal variables. For numerical variables median and interquartile range were calculated. If no “n” value is shown, data were available for all study participants. Statistical analysis was performed with Pearson's chi-squared Test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant and highlighted in bold. A multivariate binomial logistic regression analysis was performed including clinically and statistically relevant predictor variables.

- Abbreviations: Anti-S RBD, anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain; BMI, Body Mass Index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LCP, Liver cirrhosis patients; LTR, liver transplant recipients; NC, anti-Nucleocapsid antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Overall, we find almost complete vaccination coverage in spring 2023. The rate of vaccine refusers was very low (<3%) and approximately 60% of patients had received at least 4 vaccinations, in some cases even up to 6 doses. Additionally, just over two-thirds of patients and all vaccine refusers developed a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. In LTR, the overall hospitalization rate of 5.5% for complications related to COVID-19 was higher than previously reported in the general population,21 but much lower compared to initial reports for this patient population.1, 10, 22, 23 Presumably, this is due to the large numbers of infections that occurred during the Omicron wave in the second half of 2022 in patients with robust vaccination status.

Thus, in spring 2023, after an average of 4.3 (range: 1–8) spike antigen exposures due to vaccination and/or SARS-CoV-2 infection (Suppl. Figure S1), almost all patients showed a humoral immune response to the spike antigen. A high anti-S RBD titer was found in more than half of the patients, but 17.5% of LTR and 8.3% of LCP still had low titers (<1000 AU/mL). In accordance with previous results of the general population, a SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered a higher anti-S RBD titer compared with an additional vaccination (Figure 3).15, 24-26 Thus, only after a natural infection LTR and LCP reached the median anti-S RBD level of HC after the third vaccination.4, 15 Although there is no cut-off level known that offers protection, higher SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels have been demonstrated to decrease the risk of severe COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients.10, 22

Another result of this study indicating a less robust immunity in the population examined than in healthy individuals is the negative or only low T-cell response in as many as 24.6% and 20.4% of LTR and LCP, respectively. Also, there were no differences evident between infected and vaccinated patients regarding T-cell immunity determined by IGRA (Figures 3b,d). Previously, Kirchner et al. reported a stable cellular immune response over 1 year in convalescent LTR despite a decline in the humoral response.27 The clinical significance of a low cellular SARS-CoV-2 immune response in these patients and ways to overcome this require further investigation. However, there is a general understanding that the T-cell response is essential in preventing severe disease courses.22, 28, 29

Although the anti-S RBD is typically used to assess immune competence, low anti-NC antibody levels were previously found to correlate with more severe clinical outcomes in healthy subjects,30 and potentially play a role in the protection against severe COVID-19. In our cohort, anti-NC antibodies were absent in 22% of patients despite a confirmed previous infection within a median time period of 8 months. Also, in our study, lack of anti-NC antibodies was associated with lower anti-S RBD levels and poor renal function, which are both risk factors for a severe course of COVID-19.6, 10, 22

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our single-center study conducted in Germany, as the findings are not necessarily directly applicable to other countries. Furthermore, due to our cross-sectional study design, we could not assess mortality rates. In addition, the exclusion of patients who died of COVID-19 entails a potential bias since these patients might have had a particularly weak immune response. However, overall, we are aware of only two LTR from the Liver Transplant Center Hamburg who died of COVID-19. Also, the study design does not allow the delineation of whether immunity was induced by vaccination or infection, nor does it allow assessment of the waning immune response over time, as previously investigated by others.31, 32

In summary, we found an overall high vaccination coverage and infection rate in spring 2023, which resulted in spike-seropositivity in almost all LTR and LCP. However, a proportion of patients still lacked a sufficient humoral or cellular immune response. Therefore, while for most patients, future breakthrough (re)infections will probably pose only a small risk of developing a severe course, it is important to note that older patients with several comorbidities and lower immune responses might remain susceptible to a more severe disease. Furthermore, the level of protection against potential future variants, and also against the currently prevalent XBB variants, remains unclear. Given the patients' decreasing motivation to receive additional vaccine doses,33 healthcare providers should encourage vaccination according to current guidelines and offer advice based on the individual immune status and risk of severe disease. Prospective studies should assess the immune response to vaccines targeting new variants. Additionally, there is a medical need to better understand the risk of developing a severe course or long-term sequelae of COVID-19 due to re-infections in immunosuppressed patients.34, 35

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all study participants and contributing departments of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf for their active participation in the study. The authors would like to thank Maria Marder for her assistance and support in the laboratory work. Julian Schulze zur Wiesch received research funding from SFB1328, project A12 and DZIF; Marylyn Martina Addo reported funding from the DZIFTTU 01709. No further funding was used in the reported research. We acknowledge financial support from the Open Access Publication Fund of UKE - Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf and DFG – German Research Foundation.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare that they have no known competing financial, professional, or personal conflicts that could have influenced the work reported in this paper. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee of Hamburg, Germany (Reg. Numbers PV7103 and PV7298; 28/01/2021) and the Paul Ehrlich Institute, the German Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines (Reg. number NIS508).

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Individual participant data will not be shared.