Effects of a single exercise workout on memory and learning functions in young adults—A systematic review

Abstract

Background

Physical exercise improves mental health and cognitive function. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the current literature examining the acute effects of a single exercise workout on learning and memory functions in young adults.

Methods

The review was conducted in alignment with the PRISMA guidelines. Studies were included if they were indexed in PubMed, published between 2009 and 2019, used an experimental study design and conducted on young human adults. The MeSH terms “exercise,” “learning,” and “young adults” were used together with the filters Publication dates—10 years; Human Species; and Article types—Clinical Trial.

Results

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated. The types of exercise stimulus that were used was walking, running, or bicycling. Several different test instruments were used such as Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test A and B, and Stroop Color Word Test. Exercise for two minutes to one hour at moderate to high intensity had a favorable effect on learning and memory functions in the selected studies.

Conclusions

This systematic review shows that aerobic, physical exercise before encoding improves learning and memory functions in young adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

Exercise usually refers to a physical or mental activity to improve health, well-being, a physical or mental skill. Physical exercise improves mental health and cognitive function.1, 2 Children who exercise regularly and have a high aerobic capacity perform better on tests of memory and cognitive function than those who do not exercise.3 High aerobic capacity and cognitive function in children are linked to high blood flow, volume and neuroplastic function in the hippocampus as well as better memory function.4-6 Furthermore, exercise in children leads to a thinning of the gray substance in the frontal cortex, upper temporal area, and lateral occipital cortex, which is associated with improved mathematical and arithmetic ability.7 Regular exercise increases microstructures in the white matter of the corpus callosum which integrate cognitive, motor and sensory information between the hemispheres and are of importance for cognition and behavior in children.8 A number of studies have shown links between regular exercise and cognitive function in children, teenagers and the elderly, but there is a lack of studies in young adults, here defined as individuals between 18 and 35 years of age.

There are three phases in the learning process when information is stored in memory denoted encoding, consolidation, and retrieval.9 Encoding takes place immediately and includes processing of the information. Subsequently, the consolidation phase follows when information is moved to the more stable long-term memory.10 There are several types of memory including sensory memory, short-term memory, working memory, and long-term memory.9 The latter could be divided into explicit/declarative memory (memory of facts, data, and events), implicit/procedural memory (unconscious memory or automatic memory), and prospective memory (ability to remember to carry out intended actions in the future). Studies have shown that recall of information is improved when emotional stimulus and exercise is added.11-13

Several single studies have shown that chronic, repeated physical exercise improves cognitive functions, learning, and memory. However, review studies with meta-analysis analyzing the effect of a single, acute exercise activity have reported varying effects from favorable to small or adverse effect.14-16 Exercise duration, intensity, and type of cognitive performance assessed seems crucial for the outcome. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the current literature examining acute effects of a single exercise workout on learning and memory function in young adults.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

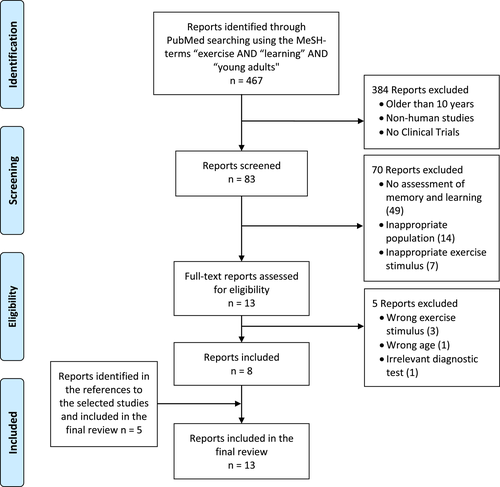

A systematic review was conducted in alignment with the PRISMA guidelines. Studies were included if they were indexed in PubMed, published between 2009 and 2019, written in the English language, used an experimental study design (ie, a randomized, controlled trial using an exercise intervention) and conducted on healthy young human adults (Figure 1). Reports were accepted if the participants were between 18 to 35 years of age. Studies of one or both sexes were accepted. Studies on subjects with a specific disease or condition were excluded. The participants were randomized to either rest or exercise alternatively; they completed both sessions and were their own controls. Physical aerobic exercise on a bicycle ergometer, walking, and running was accepted as exercise interventions. Only reports conducting neuropsychological tests of learning, memory, and cognition were accepted.

3 RESULTS

The PubMed search was conducted using the following terms: ((”exercise”[MeSH Terms]) AND (”learning”[MeSH Terms]) AND (”young adults”[MeSH Terms])). This search resulted in 467 unique studies. Next, the filters “Publication dates, 10 years,” “Human Species,” and “Article types, Clinical Trial” were applied yielding 83 studies whose titles and abstract the author No.1 reviewed.

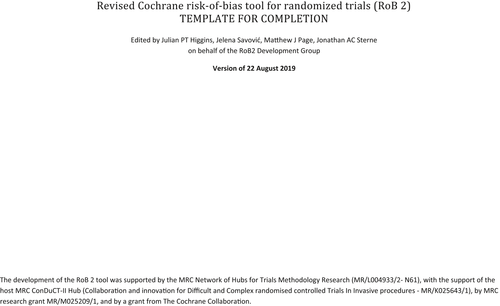

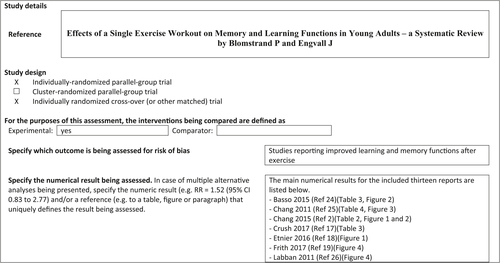

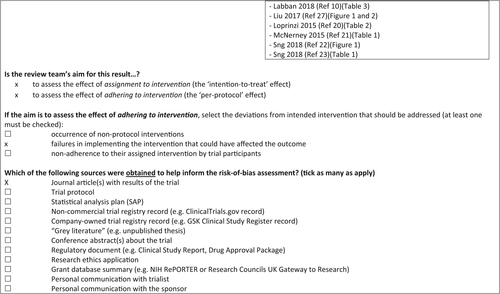

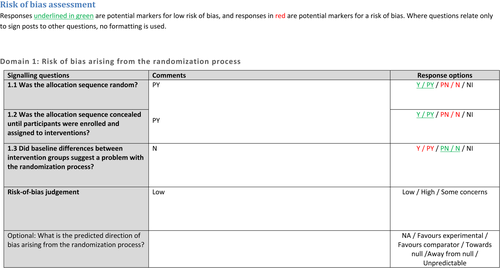

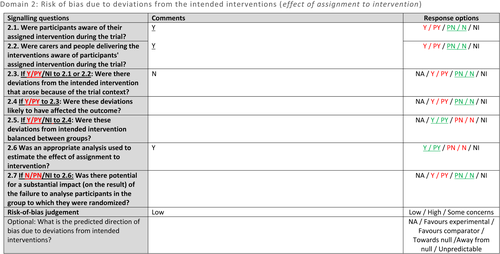

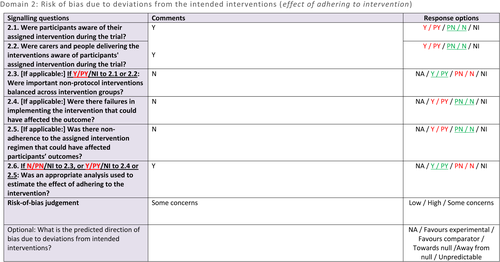

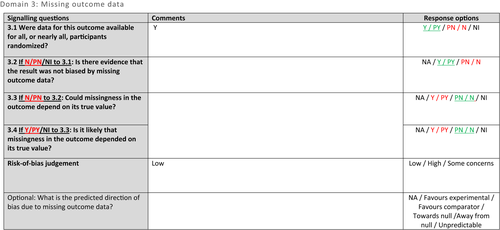

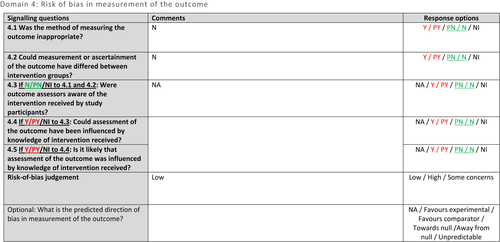

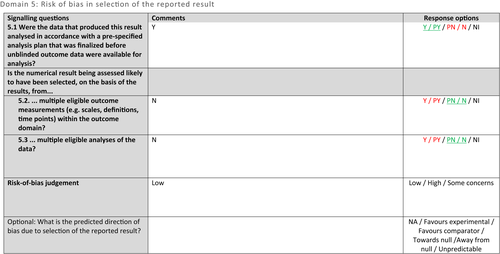

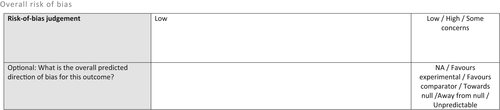

Forty-nine studies were excluded since they did not assess memory and learning functions. Twelve reports were omitted since they concerned studies of patients with a specific disease or condition. One study was performed on non-humans and another on adults >35 years. Seven studies did not involve an exercise stimulus and were excluded. Thirteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the study. These thirteen studies were scrutinized in their entirety by author No. 1. Five studies were excluded: two examined the effect of chronic and not acute exercise, one investigated both young and old adults, one investigated the effect of prolonged exercise-induced fatigue, and one did not concern effects on learning and memory. Eight studies met the established criteria and were included in the study. Another five studies were identified from the references published with the eight initially included studies. In total, thirteen studies were included in this systematic review. A Cochrane “Risk-of-Bias2”-analysis was performed, which found low risk of bias as for the outcome of the systematic review in relation to the included primary studies, see Appendix.

Results of the thirteen evaluated studies are shown in Table 1. The participants were randomized either to exercise versus rest, or within subject repeated measures using different exercise and rest protocols. The exercise stimulus used in the studies were walking, running, or bicycling varying from light and moderate to vigorous intensity. Seven studies used walking or running and six studies used bicycle ergometer as physical activity to improve learning functions.2, 10, 17-27 The duration of the exercise stimulus varied between 2,21 15,19, 22, 23 30,10, 18, 25, 26 and 60 minutes.24 Two studies analyzed the impact of several different durations (10-60 minutes).2, 17

| Author and citation | Year | Study design |

Population Age Gender |

Characteristics of exercise stimulus | Instruments | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basso et al 24* | 2015 |

Experimental randomized controlled design. |

Young adults 18-35 y, mean age 22 y. n = 85 (51 female) (34 male) |

Subjects were randomized to two groups: Fifty minutes cycle ergometer exercise at high intensity, 85% of maximal heart rate (n = 43) Video watching, Serie 24, for 60 min (n = 42) Randomly assigned to accomplish cognitive testing after 30, 60, 90 or 120 min recovery. 10-12 subjects from each group at each test session. |

- Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised - Modified Benton Visual Retention Test - Stroop Color Word Test - Symbol Digit Modalities Test - Digit Span Test Forward and Backward - Trail Making Test A and B - Controlled Oral Word Association Test - Wechsler Test of Adult Reading |

Bicycle exercise for 60 min improves prefrontal cortex-dependent function such as cognitive areas of working memory, processing speed, verbal fluency, and cognitive inhibition. Hippocampal functioning such as spatial memory, object recognition, passive avoidance learning did not improve. The effects remain for 30-120 min. |

| Chang et al 25* | 2011 | Experimental randomized controlled design. |

University students 22 ± 2 y. n = 42 (29 female) (13 male) |

Two groups: Bicycle exercise for 30 min at moderate to high intensity (n = 20). Text reading for 30 min (n = 22). Cognitive tests were done before and immediately after exercise or text reading. |

- Tower of London test | An acute bout of aerobic exercise on moderate to high-intensity level improves executive functions of planning and problem-solving. |

| Chang et al 2 | 2015 | Repeated measurements within group presented in a randomized counterbalanced order. |

University students 21 ± 1 y. n = 26 (all male) |

All participants completed four sessions: - 10, 20, and 45 min of exercise using a cycle ergometer at moderate intensity. - Rest. Text reading for 30 min. Five minutes later the cognitive test was conducted. |

- Stroop Color Word Test | Twenty minutes of bicycle exercise at moderate intensity improves verbal selective attention, whereas shorter or longer durations of exercise have negligible benefits. |

| Crush & Loprinzi 17* | 2017 | Counterbalanced, crossover randomized controller design using 16 groups. |

Young adults 18-35 y. n = 352. (258 female) (94 male) |

16 groups: Running on a treadmill at moderate intensity for 10, 20, 30, 45, or 60 min. 5, 15, or 30 min of recovery. |

- Trail Making Test A and B - Spatial Span - Stroop Color Word Test - Tower of London Test |

1. A short recovery period (ie, 5 min) may improve memory functions but not planning-based cognitive functions. 2. Exercise durations of 10-60 min may have different effects on memory, based on the recovery period. Cognitive functions improved only when exercise was followed by 5 min of recovery. 3. Acute exercise may have a more beneficial effect on verbal selective attention and memory functions in those with low cognitive ability. |

| Etnier et al 18 | 2016 | Repeated measurements within-group design. |

Young adults 23 ± 2 y. n = 16 (7 female) (9 male) |

All participants completed three sessions: - One session running on a treadmill at high intensity for 30 min. - Two sessions running on a treadmill at moderate intensity for 30 min. |

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, 30 min and 24 h after exercise |

No significant difference in effect on short term, memory between exercising at high and moderate intensity. There was a nearly significant difference in learning as a function of exercise intensity. Running at high intensity improved long-term memory as assessed after 24 h more than running at moderate intensity. |

| Frith et al 19* | 2017 | Randomized controlled design using four groups. |

Young adults 22 ± 2 y. n = 88 (48 female) (40 male) |

Four groups: Running on a treadmill at high intensity for 15 min before learning. Running on a treadmill at high intensity during learning. Running on a treadmill at high intensity after learning. Control group. |

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, 20 min and 24 h after exercise. |

High-intensity exercise prior to memory encoding enhances long-term memory both 20 min and 24 h after exercise. There was no difference between the groups regarding short-term memory |

| Labban & Etnier 26* | 2011 | Randomized controlled design using three groups. |

University students Mean age 22 y. n = 48 (33 female) (15 male) |

Three groups: Bicycle exercise at moderate intensity for 30 min before exposure. Bicycle exercise at moderate intensity for 30 min after exposure. Rest for 30 min before exposure. |

- Standard New York University Paragraphs for Immediate and Delayed Recall, 60 min and 24 h after exercise | Moderately intense exercise enhances long-term memory when it occurs before encoding. |

| Labban & Etnier 10 | 2018 | Repeated measurements within-group design. |

University students Mean age 22 y. n = 15 (10 female) (5 male) |

Participants completed three sessions: Bicycle exercise for 30 min at moderate intensity before encoding. Bicycle exercise for 30 min at moderate intensity after encoding. Rest for 30 min before encoding. |

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, 60 min and 24 h after exercise | Students who exercise at moderate intensity before encoding have significantly better recall at 60 min and 24 ho than those who do not exercise. |

| Liu, Sulpizio, Kornpetpanee & Job27* | 2017 | Randomized controlled design using two groups balanced for gender and age. |

University students Mean age 20 y. n = 40 (20 female) (20 male) |

Two groups: Exercise using a bicycle ergometer at moderate intensity during learning. Conventional learning at rest. |

- Word-Picture Verification Task - Sentence Semantic Judgement Task |

Students who perform physical exercise while learning English improve their learning. Physical activity improves long lasting linguistic ability and sentence processing. |

| Loprinzi & Kane20 | 2015 | Counterbalanced, crossover, randomized controlled design. Participants were randomized to four groups. |

University students 21 ± 2 y. n = 87 (36 female) (51 male) |

Four groups: Running on a treadmill for 30 min at light intensity (n = 24). Running on a treadmill for 30 min at moderate intensity (n = 24). Running on a treadmill for 30 min at high intensity (n = 22). Rest (no exercise) (n = 19). |

- Trail Making Test A and B - Spatial Span - Paired Association Learning Task - Grammatical Reasoning Test - Odd One Out - Feature Match - Polygon - Spatial Search - Spatial Slider - Trail Making Test A and B |

Moderate-intensity exercise improves concentration-related cognitive functions. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with reasoning-related cognitive function. |

|

McNerney & Radvansky |

2015 | Randomized controlled design using two groups. |

University students 19 ± 1 y. n = 136. |

Two groups: Five minutes stretch followed by two minutes of sprint at high intensity and 3 min break. - Sudoku for 30 min. |

- Serial Order Task - Paired Association Learning Task - Sentence Memory Test |

Exercise prior encoding improves procedural memory and sentence memory but not paired-associate learning. |

|

Sng, Frith, & Loprinzi |

2018 | Quasi-experimental design. Participants were classified into four different groups. |

University students 23 ± 4 y. n = 88. (42 female) (46 male) |

Four groups: Walking on a treadmill at moderate intensity for 15 min followed by 5 min rest before learning (n = 22). Walking on a treadmill at moderate intensity for 15 min during learning (n = 22). Walking on a treadmill at moderate intensity for 15 min after learning (n = 22). Rest 20 min before learning (n = 22). |

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test - Red Pen Task 20 mi and 24 h after learning |

Fifteen minutes of walk at moderate intensity before encoding improves learning and long-term episodic memory. |

|

Sng, Frith, & Loprinzi |

2018 | Randomized, controlled design using two groups. |

University students 22 ± 2 y. n = 44. (29 female) (15 male) |

Two groups: Running on a treadmill at increasing intensity for 15 min followed by 5 min rest before learning Rest 20 min before learning |

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test | Fifteen minutes of high-intensity exercise before encoding improves learning and memory. |

- * Studies found in the originally PubMed search.

There were several instruments used for assessment of cognitive function, memory, and learning in the selected studies (Table 1). Most frequently used was Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test A and B, and Stroop Color Word Test. There was a predominance of tests that measure verbal memory, short-term memory, learning, and visual perception.

Exercise at moderate to high intensity improved learning memory, planning and problem-solving, concentration-related cognitive functions, long-term memory, working memory, verbal fluency but not spatial memory, object recognition, or passive avoidance learning. The effects remained for 30-120 minutes. A short, 5 minutes of recovery, before encoding improved memory functions. Exercise durations of 10-60 minutes may have different effects on memory functions based on the recovery period. In summary, the studies showed that a single boost of aerobic exercise workout followed by a brief recovery before encoding improves attention, concentration learning, and long-term memory in young adults.

4 DISCUSSION

This systematic review shows that aerobic exercise improves the learning ability and storage in memory when exercise is performed before and in close connection with the learning activity.

How long time should the exercise effort should last and with what intensity to get the most beneficial effect on learning? In these studies, there is support for exercise sessions from a couple of minutes to one hour in duration of moderate to high intensity. Two studies compared different lengths of the efforts one of whom recommended a bicycle exercise session consisting of a 5 minutes warm-up, 20 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise, and a 5 minute cooldown.2 Crush and Loprinzi claimed that the duration of exercise might be important for cognition but is less important for the memory function.17 Two studies compared physical training of different intensity with conflicting results. One study found support for high-intensity exercise being preferable and the other for moderate intensity being best.18, 20 Crush and Loprinzi compared recovery periods from 5 to 30 minutes and found that a short recovery of 5 minutes may have favorable effect on memory functions but not on planning ability.17 Whereas exercise improves the first encoding phase of learning, exercise immediately after learning, in conjunction with the consolidation phase, has less favorable effect.10, 19 Several cognitive functions associated with learning were improved after an exercise stimulus in the selected studies such as: attention, concentration, working memory, short-term memory, long-term memory, verbal fluency, and capability to plan and solve problems. These higher orders of executive processes are depending on the prefrontal cortex.24 However, more studies are needed to identify optimal exercise strategies to improve learning and memory.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how acute exercise can improve memory and learning functions. Exercise-induced long-term potentiation (LTP) represents a sustained post-synaptic potentiation and a cellular mechanism of episodic memory function.28 Physical activity may induce plasticity-related proteins that tag nearby synapses for capturing by the memory stimuli.29 Exercise may enhance attention and memory encoding through modulation of dopamine transmitters and increase the expression of dopamine.30 Animal studies have demonstrated increased post-synaptic excitatory activity and improved long-term memory after high-intensity exercise.31, 32 Physical training may affect the levels of cAMP-responsive element binding protein-1 (CREB-1) and neuronal excitability which may facilitate prime neuronal cells to encode memory.33, 34 Brain-derived neutropic factor (BDNF) may also promote memory functions.18 In summary, several mechanisms have been suggested but more research is needed to understand how morphological, neurochemical, and electrophysiological alterations in various regions interact.

5 PERSPECTIVES

The present study provides knowledge about how a single boost of aerobic exercise workout improves attention, concentration, and learning and memory functions in young adults. Identifying optimal exercise strategies may have important education-related implications.

6 LIMITATIONS TO THE STUDY

There are some limitations to the study. A meta-analysis would have strengthened the validity of the paper but was not performed. The search was only performed in PubMed and limited to the last 10 years. There are several older studies published in the field.12 There are other databases available such as PsycINFO (American Psychological Association) and ERIC (Institute of Education Sciences), however, PubMed is the far greatest of them all and covers the knowledge area. The delimitation is performed in order to focus on the current state of knowledge. Exercise in the form of walking, running, and bicycling has been used as exercise stimulus without findings supporting that these forms of activity would improve learning better than other forms of exercise. However, in our review, the results are comparable regardless of type of exercise used.

7 CONCLUSION

This systematic review strongly suggests that aerobic, physical exercise followed by a brief recovery before encoding improves attention, concentration, and learning and memory functions in young adults. The results of this review may have important education-related implications. Identifying optimal exercise strategies may help students to enhance their learning and memory.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.