The Big Family: Informal Financing of Small- and Medium-Sized Businesses by Guanxi

Abstract

Guanxi facilitates interaction between companies and people in Confucian societies. Does this type of social construct still play the key role, when the entrepreneurs live in Western societies? The objective of this article is to verify the impact of Guanxi on the capacity of small and medium-sized businesses accessing financial resources informally. To this end, data collected from small Chinese entrepreneurs active in the principal business center of Brazil were used. From nonparametric tests, the results suggest that: (1) different levels of Guanxi allow small and medium-sized businesses to access informal financial resources; (2) different types of informal financing are mostly used, or judged to be more significant, depending on the level of Guanxi of the entrepreneur in terms of parental and nonfamily ties; and (3) unlike the Western literature on the financial cycles of start-ups, this type of informal financing can extend beyond the initial stage of the business. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Introduction

Recent studies, such as those carried out by Yang and Wang (2011), have defended the idea of Guanxi as a governance mechanism. Guanxi is essentially a social construction present in all Confucianist societies. Guanxi can be understood as a model of close relationships and exchange of mutual business favors (Kipnis, 1997; Lee, Pae, & Wong, 2001). In this line of argument, Yang (2002) proposes that Guanxi has played an increasing role in businesses developed in different economic and institutional contexts. Furthermore, in the past decade, Guanxi has been paid special attention in the academic community, notably based on their precedents and their consequences. Thus, on their precedents, the literature shows evidence suggesting that Guanxi is negatively associated with opportunism, and is positively influenced by the uncertainty in the taking of decisions and perception of similarity. In other words, it would seem that Guanxi is a form of mitigating risk in uncertain environments by means of including bonds of trust (Lee et al., 2001).

When the literature is examined for the consequences, Guanxi has been shown to contribute to the quality of relationships, interdependency, and growth of sales, but has less impact on the capacity to generate profits (Park & Luo, 2001). Evidence can also be found that in publicly traded companies, Guanxi can improve governance mechanisms and the performance of the firm from the market perspective (Luo & Chen, 1997; Yang & Wang, 2011). Thus, the research on questions in relation to Guanxi has covered both the precedents and the consequences (Wong, 2010). Furthermore, the studies on Guanxi have been characterized by the examination of the institutional environment in which large multinational companies operate, and that most of the opportunities are restricted to the Confucian region.

Few studies have specifically looked at the consequences of this type of Chinese social capital on the financing profile of the companies, although there is already a wide range of literature on finance emphasizing the importance of the use of network ties and social capital to obtain financial resources in the stages of a business or of a new venture (Berger & Udell, 1998; Shane & Cable, 2002). According to a survey carried out by Li (2006), there are different types of particular financing related to Guanxi. This approach was applied in an exploratory, qualitative, and empirical of small and medium-sized Chinese businesses in Brazil by Sheng (2008).

However, various questions still remain to be discussed. It is known that there are different levels of Guanxi, some stronger and others weaker (Lu & Reve, 2011). Guanxi may involve family or nonfamily ties. Do these differences in levels and intensity of Guanxi influence the type of financing? Which types of informal financing are most significant or most used by Chinese entrepreneurs in a more uncertain wider environment (business environment other than their cultural origin)? And what is the role of the different types (or channels) of formal financing in this context?

Given these arguments, the purpose of this study is to verify the existence of associations among various levels of Guanxi and the ability of small and medium-sized businesses to obtain informal access to financial resources in a highly uncertain business context. To this end, data were collected at the end of 2011 from a community of Chinese entrepreneurs who emigrated to Brazil, more specifically to the city of São Paulo, which is to say, an environment in which the Chinese entrepreneurs are not accustomed to the language and different institutions of another emerging economy.

- It provides empirical evidence of the characteristics of Guanxi in a Western country with an emerging economy, particularly on the different levels of Guanxi.

- It is a further study of the role of Guanxi as a form of reducing the asymmetry of information and conflict of interest between those needing and those offering capital loans in a non-Confucian institutional context.

- It offers evidence of the role that different forms of Guanxi may exercise on the gathering of informal financial resources for small and medium-sized businesses.

This article is organized into five sections, including this introduction. The next section concentrates on a review of the literature supporting the study. The third section details the methodological procedures used in the development of this study. The fourth section gives and discusses the empirical results found. Finally, the fifth section presents the final considerations of the study.

Literature Review

According to the line of thinking adopted by Venkataraman (1997, p. 120), entrepreneurialism can be seen as a process by which opportunities to supply future goods and services are discovered, created, and operated. But, assuming that people have different information and beliefs, some individuals recognize opportunities that others do not perceive (Shane, 2000). In accordance with these arguments, Kirzner (1973) advocates that it is the idiosyncrasies of information and beliefs on which there is the existence of opportunities to do business. According to this view, Shane and Venkataraman (2000) understand that if someone with the resources has the same information and beliefs as an entrepreneur, he (the one with the resources) will try to appropriate the business profits, adjusting the price of these resources to the point where the business profits will be eliminated. Furthermore, Schumpeter's (1934) point of view points to the idea that if other businesspeople have the same information and beliefs, the competition between businesspeople would eliminate the business opportunity.

This line of discussion is aligned with the idea that isolated individuals tend to have less access to information, or rather that companies that do not share ties in the context of the business milieu tend to have less access to the resources necessary to their operation (e.g., information, knowledge, status, capital). Furthermore, companies not linked in to networks of businesses tend to make redundant efforts as they do not have the access to resources already dominated by possible neighbors in the business environment. Thus, as Guanxi is a form of companies and people being included in the network, it is understood that this social construction can influence the performance of businesses, notably due to their power over the capacity of a company to access resources, including financial ones (Hwang, 1987; Yeung, 2006).

Complexity of the Guanxi Network

In the judgment of Wong (2010), China can be seen as a family formed of high-density relationships. In particular, China is a society based on Confucianism, in which people are highly connected by a variety of Guanxi, which can be seen as a network consisting of millions of Chinese firms within social and business networks, which has a strong influence on the results of these businesses (Gibb & Li, 2003; Pearce & Robinson, 2000). Also, according to Wong (2010), the definition of Guanxi is not so simple, given the complexity of questions involved in this social construction. However, according to this author, Guanxi is based on friendship and affection, on the reciprocal obligation to respond to requests for help or assistance.

To put this in another way, Guanxi networks can be seen as subnetworks (groups defined by people who share some characteristic, and this similarity is recognized as a catalyst in social interaction, in which Guanxi can take place most easily) of cells (e.g., organizations such as families or companies) consisting of individuals with Guanxi. People from the same origin tend to have affection for their hometown, this type of connection, and so forth, from one individual to another. These ties mean that individuals are seen to be connected and strengthen their ties of friendship, so that people come to interact in a kind of small world (Hammond & Glenn, 2004; Guo & Miller, 2010, p. 421).

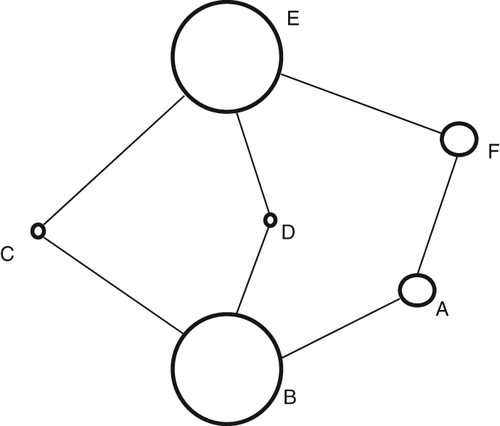

The small-world theorem explains how the interpersonal network impacts daily life: an organization or special structure in which people are connected in a regular pattern mixed in with a chaotic equilibrium (Watts & Strogatz, 1998). The small world shows a dynamic underlying the interconnection that reflects the way in which people are, think, and behave (Buchanan, 2002). Figure 1 illustrates strong and weak ties within a network. The number of degrees of separation between A and B jumps from one to four if the direct link between them is removed. The link is a kind of social bridge, a crucial connection linking the various parts of the social tissue.

Source: Elaborated by the authors from arguments developed by Wong (2010, p. 422). This figure illustrates an example of strong and weak ties in a hypothetical network. We can see that, if the tie between the vertices A and F were broken, the distance (degree of separation) between A and F goes up from 1 to 4 degrees. Put in another way, if the path A→F became impossible, these two people would be connected by a longer path (e.g., A→B→D→E→F).

In this sense, Granovetter (1973) defends the view that the weak ties are more important than the strong ties, as the former play the role of maintaining the network connection. According to arguments given by Wong (2010), a situation similar to this is found in Chinese society, and these ties (including the weak ones) are called Guanxi with differing characteristics. In examining the intuition of weak ties formalized by Burt (1992), it was understood to be reasonable to assume that weak ties are those in which, if broken, the participants of a network would have to undergo great distances (degrees of separation) to rebuild their connections. Another form of understanding is that if the ties are weak, the level of access to new information is higher. Alternatively, strong ties, if broken, require fewer steps to be rebuilt. For example, family members form a network characterized by strong ties.

- The ties originate within the family (blood ties), also pointing out that this also includes weak ties, which can be seen as a bridge by which outsiders can become insiders.

- In Chinese society, once established, strong ties become unbreakable.

- Frequent interactions with reciprocity strengthen Guanxi and bring the participants closer.

- All forms of Guanxi are rooted in the family.

According to this line of thought, Guanxi is understood to be a resource to be managed within the Confucian business environment (even if not geographically located in countries characterized by this culture), as, just like a network, each Guanxi mechanism acts like a synapse, transmitting resources (e.g., information, knowledge, coordinating activities).

Transaction Costs and Entrepreneurialism

Guanxi can be looked at from the perspective of transaction costs in which the entrepreneurs recognize the need to get out of the company in order to ensure and protect valuable resources (e.g., information, knowledge, financial resources, status or reputation), especially if the cultural context is minimized. Carlisle and Flynn (2005) share this thinking and add that the accumulation of capital by means of Guanxi (legitimacy) helps the business grow in a multicultural environment.

From Shane and Cable's point of view (2002, p. 365), one of the most representative transaction costs in the success of small businesses is the asymmetry of information. So the authors put the following question: how can entrepreneurs obtain funding to exploit opportunities when the asymmetry of information that led to the identification of funding opportunities is in itself a problem? Podolny (1993) assumes that under conditions of uncertainty, direct ties can offer an advantage to people wishing to obtain resources from others. The explanation for this behavior depends largely on two factors: social obligation and access to private information. These two factors are viable in relationships characterized by Guanxi. In a perspective of a connected domain, in relating Guanxi to the literature on social sciences, we can discuss the theme of business capital as a proxy for measurement of the results due to Guanxi. Finally, Kopnina (2005) confirms various benefits raised for Guanxi, such as the implicit family support at the start of the business, while at the same time pointing to the costs of tradition generated by this type of relationship in the building of modern small and medium-sized businesses in Singapore.

Social Capital as Guanxi Proxy

The concept of social capital has received significant attention in the past decade, both in academic studies and in public debate. However, its application to economic problems is still seen with a certain skepticism (Arrow, 2000; Dasgupta, 2000). Nevertheless, some prominent researchers in the area of finance accept the concept, incorporating it into the set of economic terms, while at the same time seeking to make use of metrics to enable the dimensioning of its importance. Becker (1996), starting from a theoretical perspective, treated social capital as a variable in which the usefulness of an individual is considered. Some empirical approaches to social capital have been given by authors such as Knack and Keefer (1997), Knack (1999), Cooke and Wills (1999), and Temple (1999).

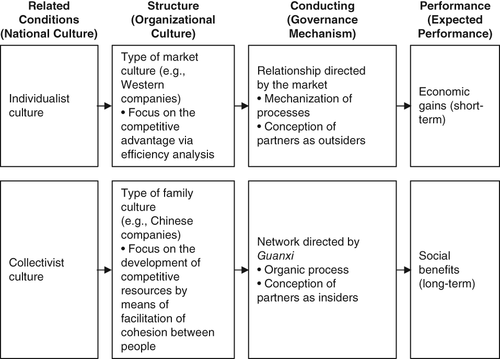

There are various conceptions for social capital, and one definition given by Westlund and Bolton (2003) is based on the argument that social capital can be seen as a kind of nonformalized social network (such as Guanxi) made up of the agents in a network with rules, values, preferences, and other attributes and social characteristics. Fukuyama (2000) defines social capital as an informal rule that promotes cooperation between the individuals. In the economic sphere, transaction costs are reduced, and in the political sphere, it promotes the kind of associative life necessary to the success of governments and of modern democracy. Arrow (1972) assumes that the central element of commercial transactions is trust, and also attributes the lack of such to explain the economic backwardness of some countries around the world. The literature shows differences in the set of determinant aspects in the acquisition of social capital in collectivist societies (such as the Chinese one) and individualist (such as the Western ones). Thus, extensions and the precedents of social capital are analyzed in a comparative approach (Wong & Leung, 2001). Figure 2 illustrates the differences found in these two types of social organization in summarized form, as discussed by Lovett, Simmons, & Raja (1999) and by Vanhonacker (2004).

Source: Extracted from Li, Chang, and Hsieh (2010, p. 381). This figure shows the conceptual model of the process of acquisition of relational capital in the western world and in Chinese culture, in summarized form. One can see that the orientation toward economic gains, the consideration of partners as being outside of the business, due to the priority of the individualist culture in the western world, in diametrically opposite position to that of Chinese culture.

Luhmann (1998) assumes that the meaning of the word trust is centered on the ability of certain organizations to function satisfactorily or, rather, the expectation that experts are able to develop their role in the context of the organizations. In this sense, treating Guanxi as a social construct in the form of a network, one can treat social capital as one representation of Guanxi, just as social capital supports the formation of networks; that is, social capital induces trust, which in turn determines the making and maintaining of ties (Buskens, 2002). Furthermore, as small and medium-sized businesses are less formalized and frequently less transparent, they face obstacles in obtaining access to capital. In this context, personal ties can be a channel for access to resources characterized by trust and of lower informational asymmetry (Berger & Udell, 1998, p. 622).

Legitimacy and Social Ties

The notion of reciprocity is not grounded in the market economies, but rather on the informal exchanges of goods, favors, and work. In principle, this is sharing something without someone necessarily expecting something in return. The reciprocity, according to Mauss (1969) tends to maintain the social order, as it balances ties and leads to the perception that an individual needs the other. This vision is shared from a cultural script. Sahlins (1972) suggests that reciprocity is entrusted with establishing the equilibrium of the relationship between two close individuals, which is at times characterized by the convenience of return.

The actions of reciprocity between friends are not of the “give-and-take” type (Halpern, 1997, p. 842), consisting of positive reciprocity. Immediate retribution, when strong ties are involved, may even be taken as an offense by the players, as if it were a payment for services rendered, rather than being an alliance. In return, when the ties are weak, in Sahlins's view (1972), the reciprocity is more easily controlled by a negative, that is, the idea that the players take more than they give.

Self-interest, rather than the interest of the other, is frequently seen as an a priori motivation in transactions involving distant individuals (strangers/weak ties), meaning that violation of contracts or other selfish behavior is possible (Castanzias & Helfat, 1991). However, when motivational factors other than self-interest are considered, such as the need for realization or friendship by affinity, the players may behave in a way in which the interests of the other are given priority (Seabright, Levinthal, & Fischman, 1992). A contribution to behavioral finance is that the notion of “friendship” as well as its script, differs from the rational perspective, which assumes the maximization of utility to the individual themselves. Put in another way, the decisions in the transactions are not necessarily toward the well-being of the friend. This is the argument of the traditional view of the economy, based on the rationality of the investor, disputed initially by Tversky and Kahneman (1974).

In exchange relationships between friends there is one component to be considered, the socially constructed role of the meaning of friend, which is common in Guanxi. Despite the difficulties inherent to the definition of the term, the expectations generated in relation to the behavior of an individual seen as a “friend” include aspects that establish the scripts of “friendship” in transactions, as listed by Halpern (1994, p. 3). In this context, Cummings and Anton (1990) argue that an individual (in the role of agent) may be taken to act in benefit of friends (in the role of principal), even when their friends (principal) do not know they are receiving such attention (from the agents). Thus, the role of “friend” supposes that the conduct of individuals is more toward the role of friend than the actual role of player. So the friends, in the role of agents, want to do something for their friends, in the role of principal, which is better than they would do for an unknown person or one who is outside their circle of personal relationships.

Guanxi and Financing of Business

We can see that the interest in the impact of Guanxi on the access to resources necessary to the operation of a firm is not recent (Hwang, 1987), but the resources are interpreted as general resources and not just financial ones. There have been few studies that deal specifically with the use of Guanxi to finance business activity. On the basis of small and medium-sized businesses of the Western model, Kopnina (2005) discusses the advantages and disadvantages of the traditional model of Guanxi on the organizational structure and workforce of small and medium-sized businesses in Singapore. One of the advantages found was the support Guanxi offers “hidden benefits” to the entrepreneur who manages to obtain start-up capital.

This discussion was more directly broached by Li (2006) who carried out a survey on informal financing of companies in China. This author suggests that informal financing mechanisms, such as Huei, are unstable and tend to be reduced with the improvement of the institutional financial environment.

In another study, Sheng (2008) analyzed financing of small and medium-sized Chinese businesses in Brazil, but this was an exploratory and qualitative study, as the researcher only managed to find seven cases with interviews of Chinese small and medium-sized business entrepreneurs in Brazil. The results of Sheng (2008), as well as Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt, Maksimovic, & Smith (2010), suggest that with Guanxi, entrepreneurs are able to obtain informal financing, to reduce the cost of credit, to prolong the periods of payment to local suppliers, reducing the need for investment in working capital. These results also suggest that the institutional environment influences this type of informal loans.

For the purposes of financing with the largest number of observations, most of the studies have discussed the question from the point of view of network ties and have attributed potential expansion of the frontier of knowledge of finance to this line of study.

According to the point of view of Evans and Leighton (1989) and of Casson (1982), often entrepreneurs do not have sufficient financial resources to exploit business opportunities. Thus, these authors defend the position that in situations of this nature, searching for external resources is imperative. This line of thought is present in the foundations of the theory of dependence on resources, according to which the firm will very unlikely be able to gather all the resources needed to operate from within the company, including the financial and nonfinancial resources on the markets, whether formally negotiated or not (e.g., reputation, status, and knowledge) (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Provan, 1980).

The consequences of social ties (e.g., friendship and sharing in social circles) on the financing of companies has been widely discussed in the literature on financing of new ventures. Shane and Cable (2002) defend that strong network ties is fundamental in the financing of a new business. This strong tie between entrepreneurs and seed-stage investors is based on two mechanisms: transfer of information and social obligation.

This idea is also shared by Berger and Udell (1998). Within the scope of studies in the field of small and medium-sized businesses, a recurring question is the treatment of information for the taking of financial decisions (i.e., financing and investment). The participation of insider finance (people who know the business and the entrepreneur well) is fundamental for financing of business even with little information for the external investor. These authors, in detailing the financing cycle of small and medium-sized businesses, point out that the financial resources from family ties play a limited role in the start-up phase. Along the same line of study, Engelberg, Gao, and Parsons (2012) concentrate on discussing the role of trust between the investor and the one using the resources to obtain loans.

Methodology

Data Collection

This study is based on primary data collected in the second half of 2011. Invitations were sent to 110 Chinese entrepreneurs established in the business center of the city of São Paulo, Brazil. The invitations as well as the application of the questionnaire to these entrepreneurs took place on the telephone or by means of personal visit.

- Profile social of the entrepreneur and of the business.

- Belonging to family networks (first or second degree of relationship exclusively) and nonfamily (i.e., religious and nonreligious associations).

- Attributes contributing to the formation of personal relationships networks (Guanxi).

- Relevance of the types (or channels) in obtaining finance, including the formal and informal ones.

- Frequency of use of the types of financing considered in this study.

- Destination of the financial resources obtained by the entrepreneur.

The last four parts of the questionnaire used to collect the data consisted of dimensions measured using the 10-point Likert scales, where 1 represents completely irrelevant aspects and 10 represents extremely important aspects.

It should be underlined that due to the difficulty of access to entrepreneurs (even using Mandarin interpreters), the size of the set of data was relatively low considering the intention to subject the data to multivariate treatment. For this reason, nonparametric tests were used, specifically Mann–Whitney U, as an alternative quantitative treatment because of the low number of observations (Royle, 1999). Furthermore, the fact that the access to the network of personal relationships of Chinese entrepreneurs in the city of São Paulo contributed to the success of the data collection.

The respondents were made aware of the content of data to be collected and of possible discomfort that might be caused, as their consent to participate in the study did not necessarily imply their obligation to respond to all the questions asked by the authors of this study. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the majority were male individuals, most of whom speak Portuguese (essential level) and Chinese, with a medium level of education, and most of whom owned a bazaar-related establishment. In general, the longer-standing immigrants to Brazil are Chinese from China Taiwan (38.5%), whereas the most recent immigrants come from continental China (61.5%).

| Social Aspects of the Entrepreneurs | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 61.5 | 16 |

| Education | ||

| Lower school | 30.8 | 8 |

| High school | 57.7 | 15 |

| University | 11.5 | 3 |

| Born in China | 96.2 | 25 |

| Only speak Chinese | 46.2 | 12 |

| Origin in China | ||

| Continental China | 61.5 | 16 |

| Taiwan | 38.5 | 10 |

| Current age of the entrepreneurs | ||

| < 40 | 0.38 | 10 |

| Between 40 and 60 | 0.50 | 13 |

| > 60 | 0.12 | 3 |

| Age of the entrepreneurs when arriving in Brazil | ||

| < 20 | 0.12 | 3 |

| Between 20 and 30 | 0.42 | 11 |

| > 30 | 0.46 | 12 |

- Source: Elaborated by the authors from the data collected. N = 26.

| Aspect of the Company | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sector of activity | ||

| Bazaar | 14 | 0.54 |

| Clothing | 4 | 0.15 |

| Bijouterie | 3 | 0.12 |

| Electronics | 3 | 0.12 |

| Decoration | 2 | 0.08 |

| No. of staff | ||

| < 10 | 18 | 0.69 |

| Between 10 and 20 | 4 | 0.15 |

| > 20 | 4 | 0.15 |

- Source: Elaborated by the authors from the data collected. N = 26.

Variables and Analysis Tools

- Step 1: In accordance with the criteria of closeness proposed by Lu & Reve (2011), group the entrepreneurs according to their level of Guanxi in four different ways: degree of family relationship in the city of São Paulo (family ties); strong nonfamily ties, for example, religious and nonreligious associations (strong ties with associations); weak ties, whether family or at the level of local associations involving exclusively Chinese (weak Guanxi); accumulated first-degree family ties and belonging to religious associations and simultaneously nonreligious associations (Guanxi strong).

- Step 2: Test the possible association between the variables described in the first step with the aspects measured on the Likert scale (whether in relation to its relevance to the business or the frequency with which the entrepreneur has made use of this in the past 36 months), as follows:

- Bank loans: Consists of a formal instrument for obtaining financial resources for business activities used by the entrepreneurs from banking institutions.

- Huei (Li, 2006): This is the most commonly used type of financing in China. It works like a kind of “consortium,” in which the organizing leader of this consortium invites their friends and relations to take part, and they in turn invite more friends (with Guanxi) to come in. Each one of the consortium members contributes with an amount, and the total amount is to be used in the first round and without payment of interest by the leader. The nonpayment of interest is a kind of payment of an administration fee by the consortium members. After the first round, the total volume may be auctioned at a monthly interest rate or in an order predefined before the organization of the consortium. In this organization, due to the good Guanxi, the credit risks of all the consortium members are considered equal.

- Loans from close relatives: Informal agreement between first- and/or second-degree family relations in order to finance business activities.

- Loans from friends: Informal agreement between people considered close (or friends), who may have known each other personally in their country of origin and/or in local social activities, in order to finance business activities.

- Commercial credit: Consists of informal commercial agreements established between entrepreneurs and suppliers in order to grant additional periods for payments.

- Financial assistance from nonreligious associations: Informal agreement by which entrepreneurs belonging to this circle of personal relationships, predominantly from the same province in their country of origin obtain financial resources, usually of small amounts.

Empirical Results

Precedents to the Formation of Guanxi Networks

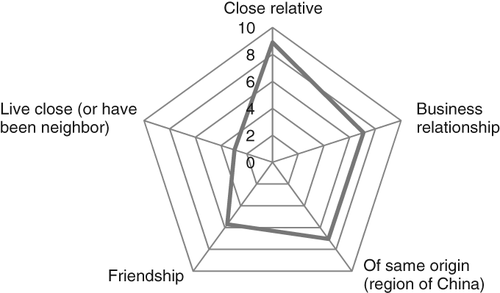

Chinese entrepreneurs in Brazil tend to favor family relationship from among the five alternatives presented in the construction of Guanxi for their businesses (Figure 3). Then, commercial interactions and provincial ties are also valued. Finally, living close by or having been a neighbor was the aspect with the least contribution. This suggests that the trust necessary for the formation of Guanxi seems to be strongly associated with the blood ties between the participants of a Guanxi network, at least from the point of view of the respondents participating in the study.

Source: Calculations by the authors from the data collected (N = 26). Note: This graphic reflects the rating (average) of relevance respondents gave to attributes of a person wanting to acquire Guanxi. Thus, on a 10-point scale (where 10 means very relevant, and 1 means indifferent), being a close relation is the most relevant attribute in the formation of Guanxi.

These results are in line with the studies carried out by Lovett et al. (1999) and Vanhonacker (2004), which suggest the differentiated treatment that individuals allege to certain people in relation to the construction of Guanxi. In addition, this evidence also corroborates studies on the existence of strong and weak ties. Assuming that Guanxi is considered to be a significant code in business transactions, this result is in line with Thaler's (1985) thinking concerning what he called transactional utility. In other words, the individuals may appreciate noneconomic attributes in the formation of Guanxi networks, and they in their turn have an influence on business transactions, suggesting that the family ties may be a decisive factor in the doing of business through Guanxi networks.

Ratings of Relevance and Frequency of Use of Types of Financing

Informal financing is both the more relevant and more used in the past three years than formal loans as sources of financing of small and medium-sized businesses with Chinese entrepreneurs in Brazil.

Table 3 shows that of the four informal sources, such as loans from relatives, commercial credit has a rating of over 6 on a scale of 10 in terms of relevance. Whereas the formal bank loan was given a rating of just 2.69, a lower rating than the consortium (Huei) and help from associations. The bank loan (2.38) was also less used in the past three years than loans from relations (4.77) and commercial credit (5.85). This result is similar to the results obtained by Sheng (2008).

| Relevance | Relevance in financing | Frequency of use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| For financing | In investments | ||

| Loans from relations | 7.24 | 4.77 | |

| Commercial credit | 6.77 | 5.85 | |

| Consortium (Huei) | 3.00 | 1.73 | |

| Bank loan | 2.69 | 2.38 | |

| Loan from friends (Guanxi) | 2.65 | 1.77 | |

| Help from association | 3.08 | ||

| Working capital | 8.38 | ||

| Seasonal sales | 8.19 | ||

| Expansion | 4.12 | ||

- Source: Elaborated by the authors from the data collected (N = 26). Note: This table shows the average values found for the types of financing and investment, according to the opinion of the 26 Chinese entrepreneurs participating in the study. If the figures in the second column are examined, we see that the loans obtained from relations were indicated as the most relevant source of business financing, and bank financing as one of the least relevant. The last column shows the average values obtained for the frequency given for the destination of the resources within the businesses, showing that working capital as more frequent than expansion of the business. The values shown in this table refer to the notes attributed by the respondents on a scale of 10 points, where 1 = Totally Irrelevant, and 10=Extremely Important.

This result is in line with the evidence found by Kopnina (2005) in small and medium-sized businesses in Singapore, where the Chinese cultural tradition helps to provide initial capital. Apart from this, this result also contributes to the study by Berger and Udell (1998), which defends the use of insider finance for nontransparent companies (with little information) in the initial stage of the business. According to these authors, insider finance consists of a source of capital through loans from the family, friends, or venture capitalists who know the business or entrepreneur very well.

In fact, this lack of transparency is present both for suppliers of finance and for Chinese entrepreneurs in Brazil who are unaware of most of the local financial instruments available due to the difficulty with the local language. Thus, Guanxi ensures transparency between the people in the same network of contacts and helps in obtaining informal finance for their business activities for working capital (rating 8.38) and seasonal sales (rating 8.19).

Influences of Business Experience of the Entrepreneur and Size of Business in the Use of Informal Financing

Although the use of informal financing is significant for small and medium-sized businesses in Brazil, it is not clear whether the entrepreneurs cease to use these types as they become more experienced in business or increase their businesses.

These results apparently suggest bias in the traditional financial studies on the importance of the use of informal financing only at the beginning of the cycle of companies (Berger & Udell, 1998) and use of network ties to finance the initial stage of a new venture (Shane & Cable, 2002). According to these authors, one would expect businesses to make use of more formal financing with the greater maturity of the business, as the uncertainty associated with the initial stage of the business lessen as time spent in the business or the size of the business increases.

The results of this study suggest that the importance of informal financing may extend beyond the initial stage. According to Table 4, only loans from friends lessen significantly, when the entrepreneurs in the sample have more experience and more number of staff. Despite the positive sign, bank loans (formal financing) are not shown to have statistically significant results. The other types of informal financing continue to be used by bigger size of companies.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bank loan | - | |||||

| 2. Huei | −0.223 | |||||

| (0.273) | ||||||

| 3. Loan from close relatives | −0.350c | 0.036 | ||||

| (0.080) | (0.862) | |||||

| 4. Loan from friends | −0.258 | 0.198 | −0.056 | |||

| (0.202) | (0.333) | (0.785) | ||||

| 5. Commercial credit | −0.255 | 0.032 | 0.275 | 0.282 | ||

| (0.208) | (0.876) | (0.175) | (0.162) | |||

| 6. Business experience of the entrepreneur | 0.106 | Ð0.200 | 0.074 | −0.479b | 0.284 | |

| (0.606) | (0.327) | (.720) | (0.013) | (0.160) | ||

| 7. Number of staff | 0.227 | Ð0.204 | −0.250 | −0.377c | 0.180 | 0.788a |

| (0.264) | (0.317) | (0.218) | (0.057) | (0.378) | (0.000) |

- Notes: Between parentheses is the p-value.

- a p-value < 0.01;

- b p-value < 0.05;

- c p-value < 0.1. The definition of the metrics related to the types of financing listed in this table is given in Subsection 4.2. For the purposes of business experience of the entrepreneur, the difference between their current age and the age when they arrived in Brazil was used, measured in years (for entrepreneurs who arrived in Brazil with less than 21 years of age, 21 was considered as the initial age). By way of proxy for the size of the business the number of staff informed by the entrepreneur was used.

- Source: Calculations made by the authors on the basis of the data collected in the study. N = 26.

One of the possible reasons that extends the importance of informal financing beyond the initial stage could be the context of high level of uncertainty of the sample used in the article, where the Chinese small and medium-sized businesses face difference of language, business practice, culture, and financing environment that impede the use of formal financing earlier.

Impact of the Level of Guanxi of the Entrepreneurs in the Choice of the Type of Financing

The results of Table 5 suggest there may be a hierarchy of preferences of informal financing by entrepreneurs. Some types of financing are more used or are considered as more relevant by one among groups of entrepreneurs with different degrees of Guanxi (family ties; strong ties with associations; weak Guanxi and strong Guanxi).

| Scales of Relevance and Priority for the Channels of Access to Financial Resources* | Grouping Variables (Belonging to Chinese Groups in the City of São Paulo) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Ties(a) | Strong Ties with Associations(b) | Weak Guanxi(c) | Strong Guanxi(d) | |

| Panel A: Relevance of types of financing for small and medium-sized businesses | ||||

| Bank loans (financial industry) | × | ✓** | × | × |

| Huei (Guanxi) | × | × | × | × |

| Loans from close relatives (Guanxi) | ✓* | × | ✓* | × |

| Loans from friends (Guanxi) | ✓** | × | × | ✓* |

| Commercial credit supplier (Guanxi) | × | × | × | × |

| Financial assistance granted by association (Guanxi) | × | × | × | × |

| Panel B: Frequency of use of types of financing for small and medium-sized businesses | ||||

| Bank loans (financial industry) | × | ✓* | × | × |

| Huei (Guanxi) | × | × | × | ✓* |

| Loans from close relatives (Guanxi) | × | × | × | × |

| Loans from friends (Guanxi) | × | × | × | × |

| Commercial credit (Guanxi) | × | × | ✓* | × |

| Panel C: Forms of use (investment) of capital in the small and medium-sized businesses | ||||

| Working capital | × | × | × | × |

| Seasonal sales | × | × | × | × |

| Expansion of the company | × | × | × | × |

- Note: This table gives the results of the nonparametric independence test between types of Guanxi in relationship to relevance and independence of channels of financing and forms of investment, by means of Mann–Whitney U test. (a) this variable groups the respondents according to their degree of relationship with their families in Brazil: first and second degrees of relationship, (b) this variable classifies the respondents in two groups: i) entrepreneurs with weak ties (second degree relationship or without family relations in Brazil) who participate in the two types of associations (religious and non-religious) simultaneously, ii) entrepreneurs in the alternative situation; (c) this variable groups the respondents in two groups: i) entrepreneurs with second degree family relations or who have no relations in the city of São Paulo and who participate in at least one association (also includes entrepreneurs who do not participate in any associations involving Chinese); (d) this variable groups respondents in two groups: (1) entrepreneurs with first degree family relations in São Paulo and who also maintain links with religious and nonreligious associations in the city of São Paulo, (2) entrepreneurs who satisfy none of the above premises.

- ** p-value < 0.05;

- * p-value < 0.1. ✓ hypothesis of equality refuted; × hypothesis of equality not refuted.

- * Panel C refers to the report from the entrepreneurs participating in the study regarding the use of the financial resources within their business (i.e. investment decisions).

- Source: Calculations made by the authors on the basis of the data collected in the study.

The Huei type stood out in the use by entrepreneurs with strong Guanxi. Entrepreneurs belonging to the group with most Guanxi in associations and who had first-degree family relations (strong Guanxi) tend to use the type of financing by Huei more frequently in comparison with individuals with no Guanxi due to associations and without first-degree family relations in the city of São Paulo, at the level of significance of 10%. It is important to remember that this does not mean that these entrepreneurs use more Huei than they do commercial credit (in terms of volume). This result is in accordance with the characteristics of high credit risk of Huei referred to in the previous sections.

This evidence converges with the low frequency of use of Huei in Table 3 (1.73) by the entrepreneurs, as only those with strong roots in all the forms of social networks manage to make use of Huei in recent years. In fact, according to reports from various entrepreneurs, Huei was more widely used in former times (prior to 1999), but with successive economic crises in recent years, the level of credit default among Huei participants was very high, and this type of financing became unsustainable. This evidence is in accordance with the argument by Li (2006) that the informal financing mechanism such as Huei is unstable and liable to suffer from economic crises. The fact that Huei is not a family loan also contributes to its instability.

Apparently, loans between friends can be substituted by financing from the family for business. Loans from friends is not considered as relevant by the groups of entrepreneurs with strong family ties and strong Guanxi (strong Guanxi group). This result suggests that the reciprocity between friends is insufficient to overcome the strength of family ties in a highly uncertain environment. Entrepreneurs belonging to the group with most first-degree family Guanxi tend to attribute greater relevance to financing by close relatives loans (family loans) as compared with individuals with second-degree family Guanxi at the 10% significance level. This evidence complements the literature that uses personal relationships to obtain resources (Engelberg et al., 2012)

Commercial credit is most used by the group of entrepreneurs with weak Guanxi. This is explained by the selective composition of this group of entrepreneurs who do not have strong family ties in Brazil and who take relatively little part in religious and nonreligious associations. In this case, they also do not consider financing by relatives as relevant to their businesses.

Finally, the results of Table 5 also suggest that Guanxi can be strengthened by greater involvement of entrepreneurs (with weak family ties) in the religious and nonreligious associations in Brazil. This result is also in line with the discussion of network initiation and network maintenance in the study by Lu & Reve (2011).

The third column shows that entrepreneurs with “strong ties with associations” not only behave differently to obtain investment than other types of informal financing, They also consider and use banks loans financing less relevant than the others.

This unfavorable judgment of the use of bank credit is also related to the lack of knowledge of the entrepreneur and the high interest rates for small and medium-sized businesses in Brazil, in accordance with the responses and comments by entrepreneurs to the final, more open questions. Only the younger interviewees with a university education responded as using bank credit for working capital. The others did not know about the bank finance procedures.

Although they did not obtain bank financing, various of these entrepreneurs make financial applications (fixed-income investment funds) with surplus cash. The main reasons for making this application is the rise of the real currency and high interest rate remuneration of funds (current nominal interest rate of Brazilian government bonds in R$ is around 11% per annum). This greater involvement of current Chinese entrepreneurs with the local bank, even in the application, is a different result than that of the study by Sheng (2008). In that study, the results suggested that Chinese entrepreneurs avoid all types of banking services.

Final Considerations

The results of this article suggest that different Guanxi levels enable the small and medium-sized businesses to obtain informal access to financial resources in a different business and cultural environment (from one emerging market to another emerging market). The informal financing are relevant and used by small and medium-sized business Chinese entrepreneurs when they are submitted, and Guanxi plays a fundamental role as a governance mechanism. This result is in accordance with that found by Sheng (2008).

In the case of Brazil, a formal loan such as a bank loan obtained only a rating of low relevance and use, whereas loans from family relations (close relatives) and commercial credit are more relevant and more widely used by entrepreneurs.

However, unlike the literature on the financing cycle and insider finance (Berger & Udell, 1998) and on the uses of network ties in the financing of new ventures (Shane & Cable, 2002), the results of this study suggest that the relevance of informal financing extends beyond the initial stage of the business. One of the possible explanations may be that the entrepreneurs of small and medium-sized Chinese businesses in Brazil have to face the difference of languages, business practices, financing culture, and environment, which may impede them from making use of facilitated formal financing.

Besides this, the results also suggest that there may be a hierarchy of preferences of informal financing by entrepreneurs. Some types of financing are more used or are considered more relevant by one of the groups of entrepreneurs with different degrees of Guanxi (family ties, strong ties with associations, weak Guanxi, and strong Guanxi).

The Huei type stands out for its use by entrepreneurs with strong Guanxi. This evidence is in accordance with the low frequency of use of Huei by entrepreneurs, as only those who are deeply rooted in all the forms of social networks have been able to use Huei in recent years due to the economic crises that affected the level of defaulting. This evidence is in accordance with the argument put by Li (2006) that the not necessarily family informal mechanisms of financing such as Huei are unstable and liable to suffer from the economic crises.

Apparently, loans from friends are not considered as relevant by the groups of entrepreneurs with strong family and strong Guanxi ties (strong Guanxi group). This result suggests that the reciprocity among friends is insufficient to overcome the strength of family ties in a highly uncertain environment. This evidence complements the literature studying personal relationships to obtain resources (Engelberg et al., 2012).

Commercial credit is most used by the group of entrepreneurs with weak Guanxi. Loans from close relatives are most used by the group of entrepreneurs with strong family ties, those with first-degree family relations. Bank loans (formal financing), in accordance with our previous discussion, are less used by the entrepreneurs who, despite weaker family ties, are able to acquire more Guanxi through their involvement with entrepreneurs in the religious and nonreligious associations in Brazil.

Thus, although some empirical results have been obtained in this study, there are limits that should be borne in mind. First, due to the difficulty in collecting data, not all of the Chinese entrepreneurs contacted in the city of São Paulo wished to give interviews. Second, the low sample size may have led to some bias in the analysis of results.

- Carry out similar studies of informal financing as this one, seeking to increase the number of observations over time.

- From a comparative approach between Confucianist and Western markets, analyze the impact of personal relationships on the capacity of small and medium-sized businesses to attract financial and nonfinancial resources (e.g., knowledge and technology).

- Analyze the precedents on the formation and acquisition of Guanxi in non-Confucian societies.

- Analyze the relationship between networks of Chinese and Western small and medium-sized business entrepreneurs, integrating the Western theory of social networks and Guanxi (Shane & Cable, 2002; Lu and Reve, 2011).

Biographies

Hsia Hua Sheng is professor of finance at Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV-EAESP) and at Federal University of Sao Paulo (UNIFESP). He is coordinator of the International Financial Management study of the Finance Institute of FGV. He graduated in economics from the University of São Paulo and holds a PhD and a master's degree in business administration (finance) from FGV-EAESP. Before joining the FGV faculty, he worked for multinational companies in Brazil, and his last position was senior manager at Deloitte, consulting division. His research interest is financial and multinational management in emerging countries, in particular financing strategies to support international finance and expansion; risk management and treasury operation to deal with cross-border investment.

Wesley Mendes-Da-Silva is a professor of finance at Fundação Getulio Vargas (São Paulo, Brazil). He is one of the founders of the Brazilian Society of Finance, and a member of the National Association of Post Graduation Studies and Research in Administration, Finance Division. He received a doctorate degree (2010) in business administration (finance), at the Economics and Administration College of the University of São Paulo. He has published papers and has received awards in Brazil and abroad, focusing on the capital market and corporate finance. His research interests are directed to the capital markets, corporate finances, behavioral finances, and entrepreneurial performance.