Characterization of exhaustion disorder and identification of outcomes that matter to patients: Qualitative content analysis of a Swedish national online survey

Abstract

Fatigue is a common presenting problem in healthcare settings, often attributed to chronic psychosocial stress. Understanding of fatigue and development of evidence-based treatments is hampered by a lack of consensus regarding diagnostic definitions and outcomes to be measured in clinical trials. This study aimed to map outcome domains of importance to the Swedish diagnosis stress-induced exhaustion disorder (ED; ICD-10, code F43.8 A). An online survey was distributed nationwide in Sweden to individuals who reported to have been diagnosed with ED and to healthcare professionals working with ED patients. To identify outcome domains, participants replied anonymously to four open-ended questions about symptoms and expectations for ED-treatment. Qualitative content analysis was conducted of a randomized subsample of respondents, using a mathematical model to determine data saturation. Six hundred seventy participants (573 with reported ED, 97 healthcare professionals) completed the survey. Qualitative content analysis of answers supplied by 105 randomized participants identified 87 outcomes of importance to ED encompassing physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms as well as functional disability. Self-rating scales indicated that many ED participants, beyond reporting fatigue, also reported symptoms of moderate to severe depression, anxiety, insomnia, poor self-rated health, and sickness behavior. This study presents a map of outcome domains of importance for ED. Results shed light on the panorama of issues that individuals with ED deal with and can be used as a step to further understand the condition and to reach consensus regarding outcome domains to measure in clinical trials of chronic stress and fatigue. Preregistration: Open Science Framework (osf.io) with DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4VUAG

1 INTRODUCTION

Fatigue is a common presenting problem in healthcare settings (Nijrolder, van der Windt, de Vries, et al., 2009), and although the precise cause of fatigue is often unclear and multidetermined (Jason et al., 2010; Wessely, 2001) symptoms are commonly attributed by afflicted individuals to psychosocial stressors such as work-related problems, problems with relationships, housing, and economy (Nijrolder, van der Windt, de Vries, et al., 2009). Stress can be defined as an adaptive psychophysiological activation in response to perceived challenges. When sustained or repeated over prolonged periods of time, stress is associated with a range of physiological and psychiatric symptoms including mental and physical fatigue (Cohen et al., 2007; Grossi et al., 2015; McEwen, 2006). Symptoms of chronic stress contribute to high societal costs due to sick leave, staff-turnover, productivity loss, and increased healthcare consumption (Hassard J et al., 2018; Henderson et al., 2011). Despite the significant impact on the individual and on all aspects of society, there is a lack of international consensus regarding how to diagnose and measure fatigue and symptoms associated with chronic stress (Arends et al., 2012; Estevez Cores et al., 2021; Grossi et al., 2015; Jason et al., 2010; Nijrolder, van der Windt, de Vries, et al., 2009). This lack of consensus obstructs the comparison and combination of results from different studies and, in turn, the development of evidence-based treatment strategies.

In response to increasing sick leave rates due to mental disorders in the late 1990's in Sweden, together with clinical observations that many sick-listed individuals reported prolonged exposure to psychosocial stressors and symptoms of fatigue, tentative criteria for a new diagnosis, “exhaustion disorder” (ED), were introduced in 2003 (The National Board of Health and Welfare, 2003). Diagnostic criteria for ED, dominated by mental and physical fatigue, were subsequently accepted into the Swedish edition of the International Classification of Diseases (SE-ICD-10, code F43.8 A; see Table 1 for diagnostic criteria) as a specification of F43.8 other reactions to severe stress. Although the clinical picture of ED largely resembles that of other fatigue-dominated constructs such as clinical burnout (van Dam, 2021), allostatic overload (Fava et al., 2019), and chronic fatigue (Billones et al., 2021), only ED has been formally included as a medical diagnosis in a major diagnostic system. Since its introduction into the SE-ICD-10, prevalence of the ED diagnosis has approached that of major depression (Höglund et al., 2020), and ED has become the number one cause for long-term sick leave of all somatic and psychiatric disorders in Sweden (The Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2020, p. 8).

| A. Physical and mental symptoms of exhaustion during at least 2 weeks. The symptoms have developed in response to one or more identifiable stressors, which have been present for at least 6 months. |

| B. Markedly reduced mental energy, manifested by reduced initiative, lack of endurance, or increased time needed for recovery after mental efforts. |

| C. At least four of the following symptoms have been present most of the day, nearly every day, during the same 2-week period: |

| 1. Persistent complaints of impaired memory and concentration. |

| 2. Markedly reduced capacity to tolerate demands or to perform under time pressure. |

| 3. Emotional instability or irritability. |

| 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia. |

| 5. Persistent complaints of physical fatigue and lack of endurance. |

| 6. Physical symptoms such as muscular pain, chest pain, palpitations, gastrointestinal problems, vertigo, or increased sensitivity to sounds. |

| D. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

| E. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., abuse of a drug or medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism, diabetes, infectious disease). |

| F. If criteria for major depression, dysthymia, or generalized anxiety disorder are met simultaneously, exhaustion disorder is set as an additional specification to any such diagnosis. |

- a All criteria with capital letters must be met to set the diagnosis.

Given the substantial societal impact of chronic stress and fatigue, there is a need for further investigation into symptom presentation, diagnostic characterization, and steps towards standards regarding outcome domains to measure in clinical trials. Indeed, a recent review of all published studies on ED, published by our research group, indicated that research on the validity of the diagnostic construct is limited (Lindsäter et al., 2022). Assessment and measurement procedures for ED vary across studies, and specific symptom presentation as well as symptom overlap with other psychiatric and somatic conditions have been insufficiently mapped (Lindsäter et al., 2022). Similar challenges have been identified also for burnout and chronic fatigue (Bianchi et al., 2021; Billones et al., 2021; Jason et al., 2010; Nadon et al., 2022; Wessely, 2001). A core outcome set (COS) is an agreed-upon set of patient-relevant outcomes to be measured in all clinical trials to increase comparability and combination of findings (Williamson et al., 2017). The development of a COS is a stepwise process that initiates with identifying patient-relevant outcome domains in a target group (the what to be measured), to eventually result in consensus regarding which specific scales and methods that should be used (the how to measure). The need for a COS for chronic stress and fatigue has been highlighted in several publications (Ju et al., 2018; Lindsäter et al., 2022; Svärdman et al., 2022), but with the exception of a consensus workshop to discuss a COS for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis (Ju et al., 2018) no such processes have been initiated to the best of our knowledge.

1.1 Objective

The main objective of the present study was to map central outcome domains expressed as important by individuals with a reported ED diagnosis and by healthcare professionals who work with ED patients. The aim was to delineate a coherent and informative set of clinical attributions that can inform choice of patient-reported outcomes and treatment development. A secondary objective was to describe the demographic- and health characteristics of respondents reporting to have been diagnosed with ED.

2 METHOD

2.1 Study design and recruitment

An online survey was distributed nationally in Sweden to (1) adults (18 years and older) who reported to have been diagnosed with ED by a healthcare professional and to (2) healthcare professionals who meet patients with ED in their clinical work (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, general practitioners, physiotherapists). To capture the full diversity of perspectives regarding sociodemographic factors and symptom domains, a range of websites and social media groups were targeted, including groups specifically dedicated to ED as well as associations for medical doctors and psychologists. Information about the study was also spread to primary and secondary healthcare centres across the country (see Supplementary Material S1 for details about recruitment). Because the survey was only available in Swedish, participation required ability to read and write in Swedish.

Study participants were guided to a webpage where they were able to read about the study and provide online informed consent before moving on to completing the survey. The survey was delivered via BASS4, a secure online platform offered by the eHealth Core Facility at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, with a recruitment period from July 6th to 30th October 2021. The study was registered on Open Science Framework (osf.io) with DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/4VUAG and was approved by the Ethical Review Agency, Sweden (Dnr 2021–02325).

2.2 Data collection

Participants responded to the survey anonymously. In the first step, they were asked to choose whether they replied as a “healthcare professional” or as a person who had been diagnosed with ED by a healthcare professional. If responding as the latter category, participants were asked to specify whether they replied as someone with “prior ED” (i.e., previously diagnosed but now in remission) or as a person with “current ED” to capture potential different phases and perspectives on the disorder.

All respondents first answered questions pertaining to sociodemographic information. Additional health information was collected from ED participants, such as number of episodes of ED, sick leave information, and treatment received. ED participants were also asked about potential stressors in the past 2 years based on stressors identified in the Adjustment Disorder New Module questionnaire (ADNM; Einsle et al., 2010). The ADNM includes 16 stressors relating to work (e.g., too much/too little work), private life (e.g., conflicts, disease, economic problems), life transitions (e.g., retirement, moving to a new home), and traumatic stressors (e.g., serious accident, assault). Healthcare professionals were asked about professional characteristics (e.g., profession, years of experience, and type of workplace).

Open-ended questions were subsequently administered to all respondents to identify symptom domains of importance for ED. The development of relevant questions for this purpose was based on the recent work of Chevance et al. (2020) in which outcome domains for depression were mapped. The questions were translated to Swedish and adjusted to the ED diagnosis in collaboration with clinicians, researchers, and a patient consultant with prior ED. An English translation of the open-ended questions used in this study is presented in the Appendix. Of note, the main purpose of the questions was to collectively elucidate different perspectives on ED symptoms and challenges described by participants, and thus they are not treated as separate questions to be answered in this paper. Finally, to further characterize the sample, ED participants were administered standardized self-rated symptom scales to assess a range of symptoms and potentially overlapping psychiatric conditions that have been identified as relevant for the ED population in previous studies (Lindsäter et al., 2022). The following self-rating scales were used:

The Karolinska Exhaustion Disorder Scale (KEDS; Beser et al., 2014) consists of nine items based on ED diagnostic criteria and common symptoms reported by patients with ED (scale range 0–54). A higher score signifies more severe symptoms and a score of 19 or more has been shown to discriminate between ED patients and healthy controls (Beser et al., 2014). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.91.

The Self-reported Exhaustion Disorder Scale (s-ED; Glise et al., 2010) consists of 4 items that follow diagnostic criteria for ED, to which respondents reply “yes” or “no”. To be classified into the self-rated ED group, participants must have answered “yes” to questions 1, 2, and 4 and have met at least four of the six conditions in question 3. The scale distinguishes between light/moderate and pronounced self-rated ED.

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Cohen et al., 1983) is the most common measure of perceived stress used in clinical trials of stress-related ill health (Estevez Cores et al., 2021; Svärdman et al., 2022) and measures how often one has perceived life as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading in the past month (scale range 0–40). A higher score indicates higher level of perceived stress. The Swedish version of the PSS-10 has been found to have good internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha 0.84) and adequate construct validity with anxiety (r = 0.68), depression (r = 0.57), and mental/physical exhaustion (r = 0.71) (Nordin & Nordin, 2013). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.87.

The Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS-S; Svanborg & Åsberg, 1994) assesses depression severity with nine items (scale range 0–54) where a score of 13–19 indicates minor depression, a score of 20-34 moderate depression, and a score of ≥35 severe depression (Svanborg & Åsberg, 1994). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.90. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) covers seven items with a scale range from 0 to 21. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90. A score of 5-9 indicates mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety, and ≥15 severe anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006). The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Morin et al., 1993) is a self-rating scale to assess insomnia severity with a scale range from 0 to 28 where a score of 0-7 suggests absence of insomnia, 8–14 sub-threshold insomnia, 15–21 moderate insomnia, and ≥22 severe insomnia (Morin et al., 1993). Cronbach's alpha was 0.90. Finally, the Self-Rated Health (SRH-5; Eriksson et al., 2001) was administered, as was the Sickness Questionnaire (SQ-10; Andreasson et al., 2018). The SRH-5 is a one-item questionnaire in which participants are asked to rate their general health status from “Very good (4)” to “poor (0)” on a 5-point scale. The SQ-10 is a 10-item scale that is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from agree (3) to disagree (0) with a maximum score of 30. It was developed to measure subjective sickness in humans and contains statements such as “I have a headache”, “I want to keep still”, “I feel shaky”. Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.82. A recent study showed mean SQ-scores in the general population of 5.4 (SD = 4.9) and 3.6 (SD = 2.7) in healthy subjects (Jonsjö et al., 2020), and ED patients that were previously recruited for a clinical trial scored on average 16.8 (SD = 5.7) (Lindsäter et al., 2018).

2.3 Analyses

All participants were included in the analysis of demographic- and health data. Responses to self-rated symptom scales completed by ED participants were analyzed separately for those responding as prior ED and current ED, by calculating means, standard deviations, and, when applicable, the proportion of participants reporting different severity levels of symptoms. The survey was constructed in such a way that each section could be saved only when all questions were completed, and hence there were no missing data.

The open-ended questions were analyzed using inductive multiple-round qualitative content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004) adapted in line with Chevance et al. (2020). Initially, five individuals (EL, FS, PR, AS, EK) completed a calibration exercise in which they independently read and coded all responses to 20 open-ended questions. Coding was conducted by dividing the full text answers to all questions into condensed units of meaning (any expression found within the text that expressed a central symptom or expected benefit of ED treatment). Each unit of meaning was subsequently given a code based on the abstracted content. Any discrepancies were solved by discussion. The remaining responses to the open-ended questions were then divided amongst the coders who coded independently. To reduce the interpretation bias, the coders had different background and training, including a clinical psychologist (PhD), a social scientist (PhD), a medical doctor (MD), a research assistant, and a psychologist student in training. In the second step, three coders (EL, FS and AS) worked together with a patient-consultant to translate codes from Swedish to English and merge and categorize the codes into a unique list of subcategories (e.g., “concentration”, “lack of energy”, “anxiety”) using both clinical, scientific, and patient expertise. All citations for respective subcategory were calculated and sustainable granularity versus loss of information were discussed on regular meetings. In the last step, the coders, the patient consultant, and a professor of health psychology (ML) worked together to arrange the list of subcategories into broader categories of symptom domains (e.g., “Cognitive symptoms”, “Physical symptoms”).

To determine data saturation (i.e., when the inclusion of new respondents in the analysis does not render a substantial amount of new response categories), a mathematical procedure described by Guest et al. (2020) was used. Random samples stratified by response category (prior ED, current ED, healthcare professional) were drawn from the total sample in incremental steps (first 25 participants from each response category, then 10 participants from each response category, and continuing with 10 participants per strata until <5% new subcategories were identified) (Guest et al., 2020). Randomization was conducted using a random number generator (www.random.org). To ensure that the final sample was representative of the total included sample, the samples were compared regarding demographic variables (sex, age, area of living) as well as profession (for healthcare professionals) and ratings of exhaustion symptoms (KEDS) for ED participants. These categories were compared using Chi2-statistics and Fisher's exact test.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Recruitment

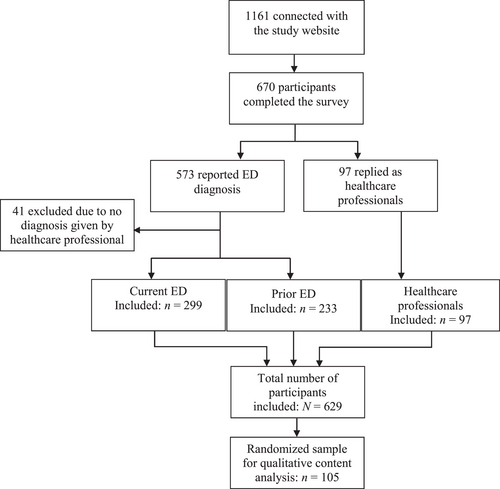

Between July 7th and Nov 1st in 2021, 1161 visitors connected to the study website. Of these, 670 signed informed consent and completed the survey (see Figure 1). Of those who initially responded as an ED participant (n = 573), 41 (7%) answered that they had not been formally diagnosed with ED by a healthcare professional and were thus excluded. The final sample consisted of 629 respondents, of which 532 (85%) responded as having a prior or current ED diagnosis and 97 (15%) responded as healthcare professionals working with ED. Of the total sample, 12% were from northern Sweden, 48% were from central Sweden, and 40% were from southern Sweden (see Supplementary Table S2 for information about recruitment in each region in relation to Sweden's total population in respective region).

Flowchart of participants through the study. Of note, exhaustion disorder (ED) and professional status is self-reported by anonymous participants. Participants who responded in the ED category (current or prior) were excluded if they reported to not formally have received the diagnosis from a healthcare professional.

3.2 Sociodemographic and health characteristics

Tables 2 and 3 present sociodemographic- and health data for ED participants and healthcare professionals respectively. ED participants were to a large majority women (497 [93%]), middle-aged (60% aged 30–49 years), with three or more years of college education (339 [64%]). A median of two previous ED episodes in life were reported (range 1–10 episodes), with a mean first age of onset of 37.8 years (SD = 9.5). Of those reporting a current ED episode, median symptom duration was 18 months (range 1–250 months) and 237 (79%) were on sick leave to some degree, mostly full time (138 [46%]). A majority (421[79%]) of ED respondents reported previous sick-leave episodes due to ED in the past 10 years, for a total median of 12 months (range <1–132 months). The most reported stressors in the last two years were “too much or too little work” (361[68%]), “deadlines/limited time” (217 [41%]), “illness of loved one” (194 [36%]), “conflicts at work” (177 [33%]), “family conflicts” (165 [31%]), “death of loved one” (124 [23%]), and “problems with economy” (121 [23%]).

| Sociodemographic and health information | Total (n = 532) | Prior ED (n = 233) | Current ED (n = 299) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 33 (6) | 18 (8) | 15 (5) |

| Female | 497 (93) | 213 (91) | 284 (95) |

| Other | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Age, years, n (%) | |||

| 18–29 | 37 (7) | 14 (6) | 23 (8) |

| 30–39 | 135 (25) | 52 (22) | 83 (28) |

| 40–49 | 186 (35) | 80 (34) | 106 (36) |

| 50–59 | 130 (24) | 60 (26) | 70 (23) |

| 60+ | 44 (8) | 27 (12) | 17 (6) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 164 (31) | 67 (29) | 97 (32) |

| Partner | 368 (69) | 166 (71) | 202 (68) |

| Has children, n (%) | 399 (75) | 182 (78) | 217 (73) |

| Nr of children, median (range) | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) |

| Region of living, n (%) | |||

| Northern Sweden | 69 (13) | 30 (13) | 39 (13) |

| Central Sweden | 242 (45) | 116 (50) | 126 (42) |

| Southern Sweden | 221 (42) | 87 (37) | 134 (45) |

| Highest education, n (%) | |||

| College/university ≥3 years | 339 (64) | 160 (69) | 179 (60) |

| College/university <3 years | 97 (18) | 40 (17) | 57 (19) |

| Secondary school 2–3 years | 87 (16) | 30 (13) | 57 (19) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Public sector | 237 (45) | 100 (43) | 137 (46) |

| Private sector | 195 (37) | 87 (37) | 108 (36) |

| Othera | 117 (22) | 61 (26) | 56 (19) |

| Current sick leaveb, n (%) | 254 (48) | 17 (7) | 237 (79) |

| Full time | 147 (28) | 9 (4) | 138 (46) |

| Part time, 75% | 35 (7) | 0 (0) | 35 (12) |

| Part time, 50% | 46 (9) | 6 (3) | 40 (13) |

| Part time, 25% | 26 (5) | 2 (1) | 24 (8) |

| Duration of current sick leave, months, n (%) | |||

| 0 to 3 | 29 (5) | 1 (0) | 28 (9) |

| 3 to 6 | 43 (8) | 0 (0) | 43 (14) |

| 6 to 12 | 54 (10) | 1 (0) | 53 (18) |

| >12 | 128 (24) | 15 (6) | 113 (38) |

| Previous sick leave episodec, n (%) | 421 (79) | 216 (93) | 205 (69) |

| Months 2011–2021, median (range) | 12 (<1–132) | 12 (<1–120) | 12 (<1–132) |

| First healthcare contact for ED, n (%) | |||

| Primary healthcare | 344 (65) | 144 (62) | 200 (67) |

| Occupational healthcare | 107 (20) | 52 (22) | 55 (18) |

| Secondary healthcared | 48 (9) | 19 (8) | 29 (10) |

| Othere | 33 (6) | 18 (8) | 15 (5) |

| Follow-up by, n (%) | |||

| Physician | 525 (99) | 231 (99) | 294 (98) |

| Psychosocial therapistf | 446 (84) | 190 (82) | 256 (86) |

| Physiotherapist | 224 (42) | 78 (33) | 146 (49) |

| Occupational therapist | 189 (36) | 60 (26) | 129 (43) |

| Otherg | 249 (47) | 109 (47) | 140 (47) |

| Diagnoses other than ED, n (%) | 390 (73) | 169 (73) | 221 (74) |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | 283 (53) | 115 (49) | 168 (56) |

| Somatic diagnoses | 258 (48) | 105 (45) | 153 (51) |

| Psychiatric and somatic diagnoses | 151 (28) | 51 (22) | 100 (33) |

| Non-pharmacological treatment, n (%) | |||

| Talking-therapy | 444 (83) | 198 (85) | 246 (82) |

| Other treatmenth | 280 (53) | 115 (49) | 165 (55) |

| Work-focused interventions | 286 (54) | 108 (46) | 178 (60) |

| Antidepressant medication, n (%) | 238 (45) | 91 (39) | 147 (49) |

| Anxiolytic/hypnotic medication, n (%) | |||

| Anxiolytic ≥1/week | 41 (8) | 16 (7) | 25 (8) |

| Hypnotic ≥1 week | 92 (17) | 30 (13) | 62 (21) |

| Anxiolytic + hypnotic ≥1 week | 41 (8) | 5 (2) | 36 (12) |

- Note: Data are integer count (%) or decimal mean (SD).

- a for example, unemployed, student, retired.

- b Due to stress-related disease or psychiatric diagnoses.

- c Due to stress-related or psychiatric diagnoses.

- d Hospital, specialist clinic (e.g., psychiatric clinic, emergency room).

- e for example, private practitioner, student health care.

- f Psychologist, psychotherapist, healthcare curator.

- g for example, nurse, assistant nurse, psychiatric aide, rehabilitation coordinator, naprapat.

- h for example, basic body awareness, mindfulness.

| Sociodemographics | HCP (n = 97) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 22 (23) |

| Female | 74 (76) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Age, years, n (%) | |

| 18–29 | 7 (7) |

| 30–39 | 32 (33) |

| 40–49 | 24 (25) |

| 50–59 | 24 (25) |

| 60+ | 10 (10) |

| Region of work, n (%) | |

| Northern Sweden | 8 (8) |

| Central Sweden | 60 (62) |

| Southern Sweden | 29 (30) |

| Highest education, n (%) | |

| College/university ≥3 years | 94 (97) |

| College/university <3 years | 2 (2) |

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Psychologist | 35 (36) |

| Physician | 34 (35) |

| Psychotherapist | 5 (5) |

| Physiotherapist | 4 (4) |

| Occupational therapist | 4 (4) |

| Othera | 15 (16) |

| Professional experience, n (%) | |

| < 7 years | 23 (24) |

| 7–15 years | 35 (36) |

| > 15 years | 39 (40) |

| Workplace, n (%) | |

| Primary healthcare | 41 (42) |

| Secondary healthcareb | 44 (45) |

| Occupational healthcentre | 6 (6) |

| Otherc | 13 (13) |

| Frequency of ED-visitsd, n (%) | |

| Daily | 29 (30) |

| Weekly | 46 (47) |

| Monthly | 19 (20) |

| More rarely | 3 (3) |

- a for example, nurse, assistant nurse, psychiatric aide.

- b Hospital, specialist clinic for example, psychiatric clinic, emergency room.

- c Private practice.

- d In the past 6 months.

Most ED participants (344 [65%]) first sought help in primary healthcare, and almost all were followed up by general practitioners (525 [99%]) as well as by a “psychosocial therapist” (446 [84%]), that is, a clinical psychologists, psychotherapist, or healthcare curator. Follow-up by physiotherapists (224 [42%]) and occupational therapists (289 [36%]) was also common. Most participants received some type of talking therapy (444 [83%]), often in combination with other therapies (280 [53%]; e.g., mind-body interventions) and work-focused interventions (284 [54%]). Concurrent psychiatric and/or somatic disorders were reported by 390 (73%) ED participants, and antidepressant medication was used by almost half of respondents (91 [39%] of those with prior ED and 147 [49%] of those with current ED).

Healthcare professionals were primarily female psychologists and physicians working in central Sweden in primary healthcare clinics (41 [42%]) or secondary specialist clinics (44 [45%]). A majority (75 [77%]) of healthcare professionals reported seeing ED patients on a daily or weekly basis.

3.3 Outcome domains for exhaustion disorder

In total, a comprehensive list of 87 outcome subcategories were identified using inductive qualitative content. Two randomized samples were drawn from the total sample of respondents. In the first sample, constituting 25 respondents from each response category (prior ED, current ED, and healthcare professionals) answers to 300 open-ended questions generated 86 subcategories of outcome domains of importance to participants. In the second randomized sample an additional 120 answers to open ended questions were analysed from 30 respondents (10 from each response category), generating only one new subcategory. Given that this addition corresponded to less than 5% new subcategories, the total randomized sample of 105 respondents was considered to provide sufficient data saturation. No significant differences were found between the randomized sample and the total included sample regarding age, sex, area of living, profession (healthcare professionals) or mean KEDS-scores (ED respondents). Supplementary Table S3 presents sample characteristics of the randomized sample on these selected variables together with statistics.

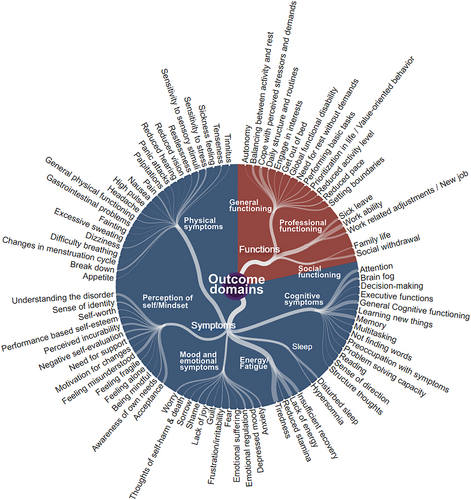

The 87 subcategories of outcomes were grouped in nine overarching categories of ED-relevant outcome domains, and subsequently divided in two major sections related to symptoms (6 categories; 69 subcategories) and function (3 categories; 18 subcategories). Figure 2 presents an illustration of the distribution of outcome categories and subcategories from the qualitative content analysis. A more detailed description of each subcategory, including example citations, can be found in the online supplement (Table S4).

Fourteen subcategories were grouped as “Cognitive symptoms”. The most frequently reported subcategories were general cognitive functioning (35 [33%]), memory (34 [33%]), attention (31 [30%]) and brain fog (25 [24%]). General cognitive functioning refers to citations where no specific cognitive symptom was specified, for example, “…but a large part [of the patients] rate the cognitive problems as the most unbearable” (healthcare professional, physician, woman). The subcategory brain fog was mostly described by participants as a sense of cloudiness of the brain and by some as a perceived slowness of thoughts. One woman with current ED, age 30–39, wrote: “It is hard to experience the world as muddy/foggy (a bit like being hungover) and having problems taking in what's going on around you…”.

Twenty-three subcategories were identified as “Physical symptoms”. The most frequently reported subcategories were sensitivity to stress (17 [16%]), break down (16 [15%]), pain (15 [14%]) and sensitivity to sensory stimuli (14 [13%]). Sensitivity to stress refers to descriptions of experiencing that physical stress reactions are triggered easily, more often or more intensely than expected, for example, “Today, it feels like my body can't withstand stress at all. Not in everyday life or for example when being physically active” (woman with current ED, age 50–59). Break down refers to the experience of total (often sudden) lack of bodily function, for example, “I really had no choice when I realized that neither my body nor my brain functioned anymore” (woman with prior ED, age 50–59) and “My body shuts down when I have done too much. I become almost paralyzed. Everything from just the legs to the whole body and speech” (woman with current ED, age 50–59).

Twelve subcategories related to “Mood and emotional symptoms” were identified. The most frequently reported subcategory was depressed mood (20 [19%]), followed by emotional regulation (19 [18%]), anxiety (15 [14%]), and worry (15 [14%]). Anxiety and worry were distinguished in such that anxiety was characterized by a more general feeling of anxiety, for example, “…as well as anxiety, immense anxiety” (woman with prior ED, age 19–29), while the subcategory worry was dominated by expressions related to a feeling of insecurity or fear regarding future events such as returning to work, getting prolonged sick leave reimbursement or ever recovering, for example, “So that I can have a social life and meet people without having to worry about being able to get up the next day” (woman with current ED, age 50–59).

Four subcategories were classified as “Energy/fatigue”: Tiredness (50 [48%]), lack of energy (43 [40%]), insufficient recovery (35 [33%]) and reduced stamina (6 [6%]). Tiredness was the most frequently reported symptom of all and was usually described in terms of being “constant” or “overwhelming”, for example, “I had been feeling incredibly tired for a long period of time…” (woman with prior ED, age 30–39). Lack of energy refers to specific expressions of not having enough energy to engage in activities like before. For example, a woman with prior ED (age 18–29) wrote “Wanting to, but not having the energy to get out and do activities”. The subcategory reduced stamina was characterized by descriptions of getting tired quickly during activities, and healthcare professionals mentioned enhanced stamina as an important sign of recovery from ED. Two subcategories related to “Sleep” were identified: Disturbed sleep (24 [23%]) and hypersomnia (9 [9%]).

Fourteen subcategories were themed as “Perception of self, and mindset”. Although not representing symptom outcomes per se, analysis of open-ended questions revealed recurrent reports of the importance of (or difficulties with) acceptance of symptoms and the reduced functional ability that they entail (27 [26%]). Other subcategories in this domain refer to the experience of feeling misunderstood (27 [26%]), which was most often reported by prior ED participants (15 [43%]), for example,: “The hardest thing is to explain to others, and additionally, you don't always understand yourself” (woman with prior ED, age 30–39). Further identified subcategories pertained to the desire to, and importance of, understanding the disorder (25 [24%]), perceived incurability (18 [17%]), need for support (15 [14%]), and sense of identity (14 [13%]).

Of the 18 subcategories that were classified as relating to functional ability, thirteen were categorized as “General functioning” where the most frequently reported subcategories were cope with perceived stressors and demands (33 [31%]), balancing between activity and rest (25 [24%]), setting boundaries (15 [14%]), and daily structure and routines (14 [13%]). Three subcategories were identified that related to “Professional functioning”: Work ability (43 [41%]), sick leave (23 [22%]), and work-related adjustments/new job (20 [19%]). Work ability was reported by a majority of healthcare professionals (20 [57%]), referring both to reduced function in work situations and to the view that returning to work is a treatment goal and sign of recovery. Sick leave was most frequently reported by current ED participants (13 [37%]). The subcategory work-related adjustments/new job was the most reported by prior ED participants (12 [34%]).

Two subcategories were classified as “Social functioning”: Social withdrawal (22 [21%]) and family life (14 [13%]). Social withdrawal was reported by all three groups but most frequently by individuals with current ED (9 [26%]) of which one answered, “To not have the energy to be with the most important people in my life and therefore having less or loosing contact” (woman with current ED, age 30–39). The subcategory family life included descriptions of not being able to, or having the energy to, engage in their children and/or partners. For example, “That you don't have the same energy as usual with the kids. You cannot put them on pause” (woman with prior ED, age 40–49) and “That you make your children or friends disappointed and sad when you totally forget a meeting or…” (woman with prior ED, age 40–49).

An additional 204 units of meaning were retrieved from participant answers that could not be classified as outcome domains. Rather, these were characterized by, for example, which types of therapeutic interventions were desired or specific behaviours that participants engaged in (such as taking a walk in the woods). For the purpose of the present study, these will not be further reported.

3.4 Symptom self-rating scales

Table 4 illustrates ED participants' scores on standardized self-rated symptom scales. Participants with current ED reported significantly more severe symptoms compared with those who responded as “prior ED” on all measures, including significantly reduced self-rated health. Of note, however, 159 (68%) of individuals with prior ED reported ED symptoms above 19 on the KEDS, which has been suggested to distinguish ED patients from healthy individuals (Beser et al., 2014), and 80 (34%) of prior-ED respondents reported pronounced self-rated ED. Approximately half of all ED participants reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression (258 [48%]), 220 (41%) reported moderate to severe symptoms of general anxiety disorder, and 225 (42%) reported moderate to severe insomnia. Individuals with both prior and current ED reported stronger subjective sickness as well as poorer self-rated health relative to general population values.

| Self-rating scales | Prior ED (n = 233) | Current ED (n = 299) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEDS (0–54), mean (SD) | 23.7 (9.9) | 34.2 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Score ≥19, n (%) | 159 (68) | 290 (97) | |

| s-ED, n (%) | <0.001b | ||

| No s-ED | 118 (51) | 24 (8) | |

| Light/moderate s-ED | 35 (15) | 18 (6) | |

| Pronounced s-ED | 80 (34) | 257 (86) | |

| PSS (0–40), mean (SD) | 18.7 (6.7) | 24.4 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| MADRS-S (0–54), mean (SD) | 15.8 (8.6) | 22.7 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Minor depression (13–19), n (%) | 72 (31) | 72 (24) | |

| Moderate depression (20–34), n (%) | 67 (29) | 152 (51) | |

| Severe depression (≥35), n (%) | 4 (2) | 35 (12) | |

| Suicidal ideationc | 10 (4) | 36 (12) | |

| GAD-7 (0–21), mean (SD) | 7.0 (4.8) | 10.0 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Mild anxiety (5–9), n (%) | 82 (35) | 91 (30) | |

| Moderate anxiety (10–14), n (%) | 46 (20) | 80 (27) | |

| Severe anxiety (≥15), n (%) | 21 (9) | 73 (24) | |

| ISI (0–28), mean (SD) | 11.2 (6.6) | 14.2 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| No insomnia (0–7), n (%) | 82 (35) | 46 (15) | |

| Sub-threshold insomnia (8–14), n (%) | 72 (31) | 107 (36) | |

| Moderate insomnia (15–21), n (%) | 63 (27) | 105 (35) | |

| Severe insomnia (≥22), n (%) | 16 (7) | 41 (14) | |

| SRH-5 (0–4), mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Quite good or very good (score 3–4), n (%) | 98 (42) | 42 (14) | |

| Quite poor or very poor (score 0–1), n (%) | 57 (24) | 180 (60) | |

| SQ-10 (0–30), mean (SD) | 13.4 (6.3) | 17.6 (5.7) | <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; ISI, Insomnia severity index; KEDS, Karolinska Exhaustion Disorder Scale; MADRS-S, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale-10; S-ED, Self-reported Exhaustion Disorder Scale; SRH-5, Self-rated health; SQ-10, Sickness Questionnaire.

- a Independent t-test comparisons between the groups “prior” and “current” ED.

- b Comparison of number of “No s-ED”, “Light/Moderate s-ED”, and “Pronounced s-ED” participants between the groups “prior” and “current” ED using χ2-test.

- c Suicidal ideation identified by a score of ≥4 on item 9 in the MADRS-S.

4 DISCUSSION

This study presents the first initiative to systematically map outcome domains that matter to individuals reporting to have been diagnosed with ED and to healthcare professionals that treat ED patients. Using qualitative content analysis of open-ended questions, 87 subcategories of outcome domains were identified, encompassing first and foremost expressions of fatigue, but also cognitive symptoms, physical symptoms, mood and emotional symptoms, disturbed sleep, and issues pertaining to self-perception. Functional impairment within both private and occupational spheres was described. Validated self-rating scales supported results from the qualitative analysis, indicating that many ED participants, beyond reporting symptoms of exhaustion, also reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, poor self-rated health, and sickness feelings. Results shed light on the panorama of issues that individuals with ED deal with and can be used as a step to further understand the condition and to reach consensus regarding outcome domains to measure in clinical trials of chronic stress and fatigue.

4.1 Outcome domains of importance to exhaustion disorder

Many of the outcome domains identified in the present study mirror diagnostic criteria for ED (see Table 1). However, because all domains were generated from detailed descriptions of participants' personal or professional experience of ED, the study contributes with more fine-grained definitions of their meaning. For example, the domain “Mood and emotional symptoms” is covered only as an optional diagnostic criterion (“emotional lability and irritability) and is most often measured using common self-rating scales of depression and anxiety in clinical trials. Results from the present study informs of a broad spectrum of experiences including fear of symptoms and difficulties with emotion regulation. These components are generally not included in symptom scales of depression and general anxiety. Similarly, the diversity of reported physical symptoms is noteworthy: twenty-three different subcategories were identified, but each subcategory was reported only by relatively few respondents. Even though several physical symptoms are exemplified in an optional diagnostic criterion for ED, results from the present study suggest a significant, heterogeneous physical symptomatology with possible implications for choice of treatment and relevant outcome measures.

The most frequently reported category identified in the present study was that of “Energy/Fatigue”, suggesting that the experience of persistent tiredness, lack of energy, and insufficient recovery constitutes a core perceived problem of individuals with ED. Importantly, Leavitt and DeLuca (2010) noted that the subjective experience of fatigue likely is a summation of a variety of factors such as sleepiness, psychiatric comorbidities, medication effects, and lack of exercise etcetera. Previous publications have pointed to the multifactorial nature of fatigue and the difficulty of identifying its exact meaning (Billones et al., 2021; Wessely, 2001). It is possible that experience of fatigue described in the present study cannot be considered a unique and delimited outcome domain, but rather that it is closely linked to other, often longstanding, symptom expressions and behavioral repertoires. For example, in a recent study by Chevance et al. (2020) in which outcome domains for depression were identified using qualitative content analysis, 15% of depressed respondents explicitly reported fatigue. There appears to be a significant symptom overlap between depression and ED, as between depression and burnout (Bianchi et al., 2021), and no consistent discrimination between fatigue and anhedonia (a component of depressive disorders defined by reduced ability to experience pleasure) has been established to date (Billones et al., 2020). Nevertheless, finding appropriate measurement scales to capture the experience of fatigue is importance to monitor the effect of treatments.

Another domain that was identified as important by participants was “Perception of self, and mindset”. This category captures how individuals view themselves, their needs, and their symptoms, factors that are not part of ED diagnostic criteria and are not commonly assessed in clinical trials. Previous studies have found that perceived competence partly mediated the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on symptoms of exhaustion in ED patients (Santoft et al., 2019), that patient expectations about fatigue chronicity is a central predictor of symptom progression (Nijrolder, van der Windt, & van der Horst, 2009), and that change in beliefs about fatigue is associated with symptom improvement (Wearden & Emsley, 2013). In speculation, an individual's mindset influences aspects of motivation and hope which contribute to building up of energy and ability to change in a chronic condition. This would correspond to findings from experimental studies in which stress mindset is demonstrated to lead to placebo/nocebo-like changes in performance as well as behavioral and biological outcomes (Crum et al., 2014, 2017). Hence, there is indication that aspects of self-perception and mindset may be of importance to monitor in clinical trials.

4.2 Characterization of exhaustion disorder

Demographic and clinical data collected from ED-participants through closed-ended questions and symptom questionnaires in the present study indicate a clinical picture that is similar to findings from previous qualitative and quantitative inquiries into aspects of ED (Lindsäter et al., 2022). The fact that a large part of participants responding as prior ED patients still reported significant symptoms is in line with findings from long-term follow-up studies of ED, suggestive of prolonged struggle with reduced energy, cognitive difficulties, and uncertainty about one's health (Ellbin, Jonsdottir, & Bååthe, 2021; Ellbin, Jonsdottir, Eckerström, & Eckerström, 2021). Importantly, approximately 50% of ED participants in the present study reported having been diagnosed with other psychiatric or somatic disorders. High comorbidity has been noted also in previous trials of ED (e.g., Glise et al., 2012; Salomonsson et al., 2019), and is a recurring theme in the fatigue literature (Billones et al., 2020; Jason et al., 2010; Leavitt & DeLuca, 2010). It should also be noted that high subjective feelings of sickness were reported in individuals with current ED in the present study, well on par with levels observed in patients with chronic pain, chronic fatigue syndrome/ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) and healthy individuals being made experimentally sick with an injection of the bacterial compound endotoxin (Jonsjö et al., 2020). In summary, findings suggest that the ED diagnosis encompasses a multifaceted and extended symptomatology that is similar to the concept of chronic/persistent fatigue (Billones et al., 2021; Jason et al., 2010; Leavitt & DeLuca, 2010) as well as with burnout (Nadon et al., 2022; van Dam, 2021) and depression (Chevance et al., 2020; Fried & Nesse, 2015). Given the limited evidence to support construct validity of ED to date (Lindsäter et al., 2022), the question of utility of the diagnosis, unique to the Swedish version of the ICD-10, is merited.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

There are several methodological strengths to this study. First, the use of both qualitative and quantitative data provides a unique possibility to deepen the understanding of ED that might contribute to the development of relevant outcome measures and novel treatment strategies. Respondents replied to open-ended text questions and were thus able to freely describe their experiences. The range of respondents (individuals in remission, individuals with current and recurring episodes of ED, and healthcare professionals) and qualitative analysts (clinicians, researchers, and a patient consultant) provides different perspectives on the ED experience which strengthens the validity of the results.

The main limitation of the study pertains to the fact that because respondents were anonymous, ED diagnosis could not be verified by clinical assessment or medical registers. Further, the sample was highly dominated by female responders (93%) which limits generalizability of findings to men and individuals with other gender identities. However, prior evidence indicates that gender differences in reported symptoms of ED are very limited (Glise et al., 2012; Glise et al., 2014), and the proportion of women in the present study is similar to what has been found in previous clinical trials on ED (Lindsäter et al., 2022). Recruitment was largely carried out online, which likely introduces some selection bias, and even though recruited individuals represented a geographical spread that largely corresponds to population size of different Swedish regions, most participants were from larger cities. Outreach might also have been limited by the comprehensiveness of the survey, as indicated by the fact that 42% of those who visited the study website did not respond to the survey.

4.4 Considerations for the development of a core outcome set

Many clinical trials of ED and other stress-related conditions use an array of outcomes to measure a multitude of outcome domains, usually encompassing a burnout measure (e.g., Shirom-Melamed Burnout questionnaire (Lundgren-Nilsson et al., 2012)) as well as measures of perceived stress, depression, anxiety, insomnia, functional disability, and different assessments of sick leave/work ability (Perski et al., 2017; Svärdman et al., 2022). The abundance of different measurement scales to assess these outcomes and the lack of a standard primary outcome measure aggravates comparisons across trials and may result in overly strenuous administration for study participants with increased risk of data loss. Further, mean scores on a variety of symptom rating scales may not capture the clinical aspects that are most important to the afflicted individual. For example, results from the present study indicate that as many as 63% of individuals with current ED report symptoms of moderate to severe depression (MADRS-S) and 51% report symptoms of moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7). When using open-ended questions to ask about the most debilitating symptoms, however, only approximately 15%–20% of participants explicitly mention depressed mood or anxiety.

In recent years, the KEDS (administered in the present study) has been suggested to be a disorder-specific, unidimensional instrument to assess symptoms of ED (Beser et al., 2014). The KEDS includes items that cover many of the symptom domains raised by participants (ability to concentrate, memory, physical stamina, mental stamina, recovery, sleep, hypersensitivity to sensory impressions, experience of demands, and irritation and anger). Of note, to date the KEDS has only been psychometrically evaluated in one study using an ED sample, and its proposed unidimensionality and international currency remains to be further investigated.

In a recent review, Billones et al. (2021) identified that eight fatigue dimensions (physical, cognitive, mental, central, peripheral, emotional, motivational, and psychosocial) are commonly measured in trials of non-oncological fatigue, with 83% of the 46 included studies measuring multiple dimensions at once. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (Smets et al., 1995), encompassing five fatigue dimensions, was identified as one of the most commonly used instrument across clinical trials of fatigue. A conclusion from the review was that, even though it may be of value to have validated condition-specific clinical measures of fatigue, psychometrics should reflect a common conceptualization of fatigue along with the use of subscales that allow for recognition of its multidimensional nature (Billones et al., 2021). International consensus regarding first-hand choice of a fatigue-inventory to be used in clinical trials of ED and other conditions related to chronic stress and fatigue might inform about potential similarities and differences between constructs and facilitate the joint quest to identify efficacious treatments.

4.5 Implications for research and practice

The high comorbidity of ED with other psychiatric and somatic disorders suggests that ED may in fact encompass a broad group of fatigued individuals with diverse psychiatric and somatic difficulties. Of note, a diagnosis of ED can be set after symptom duration of only 2 weeks, thus presenting a risk of including individuals with nonpathological fatigue and contributing to increased heterogeneity of the diagnosis. Whether reported stressors can be considered causative of the symptomatic development (and motivate a diagnostic placement in the ICD-section dedicated to “Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders”, F43) merits further investigation. Looking to the broader fatigue literature might provide guidance to distinguish between fatigue as a symptom and as a syndrome. For example, symptoms of fatigue that last fewer than 3 months and has an identifiable cause are commonly considered to be nonpathological, whereas pathological fatigue (often experienced by individuals with chronic illnesses) can be categorized into “prolonged” (1–5 months) or “chronic” (6 months or longer) (Jason et al., 2010). Suggestions have been put forth that future revisions of the DSM should include a classification of fatigue by severity, duration, and frequency (Billones et al., 2020), which might apply also to fatigue as defined in the ICD-11 (code MH22).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study presents a unique characterization of ED, a Swedish fatigue-dominated diagnosis defined by the presumed etiology of persistent psychosocial stressors. Results, based on quantitative and qualitative data collected via a national survey from 629 participants, indicate a multidimensional symptom presentation with associated functional disability that resembles international descriptions of persistent fatigue (independent of etiology), burnout, and depression. Further steps towards establishing a core outcome set, necessary to facilitate growth of evidence of much needed treatment strategies, require increased international consensus regarding definitions of fatigue and diagnostic categorization.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge and thank Margot Hinzdahl who has contributed to the qualitative analysis with the important patient perspective of a person previously struggling with exhaustion disorder. We also wish to thank Evelina Kontio for work with the initial coding procedure in the qualitative analysis, as well as Ludwig Franke and Madelene Schander for creating the illustration of outcome domains (Figure 2). This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant numbers 2020–06201 and 2021–06469), by Region Stockholm (FoUI-967372), and by AFA Insurance (190082), none of which were involved in any aspects related to study design, data collection, interpretation of results or publication.

Illustration of the distribution of categories and subcategories from the qualitative content analysis. Dots represent subcategories of outcome domains identified using qualitative content analysis of responses to 420 open-ended questions replied to by 105 randomized participants (35 individuals reporting to have current exhaustion disorder (ED), 35 reporting to have had prior ED, and 35 healthcare professionals).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1 Open ended questions posed to participants reporting to have been medically diagnosed with exhaustion disorder (ED; prior and current) and healthcare professionals working with ED, respectively

| Open questions for ED participants |

|

|

|

- Note: Questions were presented to study participants in Swedish and have been translated to English for the purpose of this publication.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENTS

All data underlying the results (e.g., full survey in Swedish and anonymous replies to closed- and open-ended questions) can be retrieved from authors upon request.