Malnutrition Risk and the Psychological Burden of Anorexia and Cachexia in Patients With Advanced Cancer

Funding: Bryan Fellman was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health through M.D. Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

ABSTRACT

Background

Patients with advanced cancer are at risk for malnutrition and anorexia-cachexia syndrome. The study objective was to determine the frequency of these conditions in patients evaluated in an outpatient supportive care clinic (SCC).

Methods

One hundred patients with cancer were prospectively enrolled to complete a cross-sectional one-time survey. We collected patient demographics, cancer diagnosis, weight history and height and Zubrod performance status from electronic health records. Patients completed the Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale (FAACT-A/CS) questionnaire, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment–Short Form (PG-SGA-SF), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and a Body Image Scale (BIS). A PG-SGA-SF cut-off of ≥ 6 indicated malnutrition risk, and loss of appetite was defined as either ESAS ≥ 3 or FAACT-ACS ≤ 37.

Results

Of the 165 patients approached, 100 (61%) completed the survey. The average (SD) age was 61.6 years old (11.5). The majority were female (52%), White (75%) and married (80%). The most common cancers were gastrointestinal (22%) and genitourinary (21%). Sixty-one per cent (61%) screened positive for risk of malnutrition (PG-SGA-SF ≥ 6), anorexia was noted in 60% (ESAS ≥ 3) and 53% (FAACT-A/CS ≤ 37) of patients, 10% of patients were noted to have a body mass index < 18.5, and 28% had body image dissatisfaction (BIS ≥ 10). Documented > 5% weight loss over the past 6 months was noted in 49%; 61% noted > 10% lifetime weight loss, relative to usual adult body weight or at time of diagnosis. Patients with anorexia (FAACT-ACS ≤ 37) compared with no anorexia reported significantly higher HADS anxiety score (4.4 vs. 3.2, p = 0.04), depression (5.9 vs. 3.5, p = 0.001), body image distress (BIS 7.2 vs. 4.9, p = 0.03) and worse appetite (ESAS 1.4 vs. 0.6, p = 0.02). Symptoms including depression, anxiety and body image distress were not significantly different between patients with either a history of > 10% lifetime weight loss or > 5% weight loss over 6 months.

Conclusions

Malnutrition risk was noted in roughly 60% of patients with advanced cancer. Inclusion of patients' body mass index to malnutrition or cachexia criteria resulted in underdiagnosis. Subjective symptoms of anorexia, but not objective weight loss, was significantly associated with anxiety and depression. Routine malnutrition screening with the PG-SGA-SF should be incorporated into all outpatient SCC visits and, comparing current weight to documented pre-illness baseline weight, should be obtained to determine the severity of cachexia.

Abbreviations

-

- ACS

-

- anorexia-cachexia syndrome

-

- ASPEN

-

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

-

- BIA

-

- bioelectrical impedance analysis

-

- BIS

-

- Body Image Scale

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- ESAS

-

- Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale

-

- ESPEN

-

- The European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

-

- FAACT-A/CS

-

- Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale

-

- HADS

-

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

-

- NIS

-

- Secondary Nutrition Impact Symptoms

-

- PG-SGA-SF

-

- Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment–Short Form

-

- SCC

-

- supportive care clinic

1 Introduction

Patients with cancer are at risk of malnutrition and weight loss which increases treatment toxicities and hospital admissions and accounts for 10%–20% of mortality [1]. In 2019, a national survey conducted in outpatient cancer centres reported that 53% implemented screening for malnutrition and only 35% reported using validated screening tools [2]. In addition, cachexia is an extremely prevalent condition among patients with cancer and is often not recognized and under-treated by healthcare providers [3, 4]. Concerns regarding weight, altered eating habits and decreased caloric intake among patients with advanced cancer have been noted to be as high as 52% [5]. Anorexia, an abnormal loss of appetite for food, can be caused by cancer, AIDS, a mental disorder (i.e., anorexia nervosa), or other diseases. Anorexia is increasingly common in patients with advanced cancer and together with weight loss is often identified as the anorexia-cachexia syndrome (ACS) [6].

In 2011, to improve recognition and treatment of weight loss, an international consensus of experts defined cachexia as ‘a multifactorial syndrome characterized by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support and leads to progressive functional impairment’ [7]. Diagnosis of malnourishment and cachexia have been defined by various criteria summarized in Table 1 [7-12]; however, no universally accepted definition or screening tool exists for either. There are some common features to both malnutrition and cachexia including loss of weight, anorexia or decreased energy intake, low BMI and inflammation. This inconsistency and complexity in definitions may be a contributor to malnutrition being used as a surrogate term for cachexia, or vice versa, by healthcare providers [13].

| Malnutrition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity | Decreased BMI (kg/m2) | Decreased energy intake | Weight loss | Loss of subcutaneous fat | Localized or generalized fluid accumulation | Loss of muscle mass (kg/m2) | Loss of muscle function | |

| Global Leadership on Malnutrition (GLIM 2018) | Moderate |

< 20 (< 70 years) or < 22 (≥ 70 years) |

≤ 50% energy reduction (ER) (> 1 week) or Any reduction (> 2 weeks) or Any chronic GI condition that impacts food absorption |

5%–10% (6 months) or 10%–20% (> 6 months) |

Not included | Not included | Mild to moderate | Not included |

| Severe |

> 10% (6 months) or > 20% (> 6 months) |

Severe | ||||||

| The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN 2012) | Moderate | Not included |

Acute injury < 75% ER (> 7 days) ≤ 50% ER (≥ 5 days) |

Acute injury 1%–2% (1 week) 5% (1 month) 7.5% (3 months) |

Mild | Mild | Mild | Not included |

|

Chronic illness < 75% ER (≥ 1 month) < 75% ER (≥ 1 month) |

Chronic illness 5% (1 month) 7.5% (3 months) 10% (6 months) 20% (1 year) |

Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | ||||

| Severe | Measurably reduced | |||||||

|

Social or environmental circumstances < 75% ER (≥ 3 months) ≤ 50% ER (≥ 1 month) |

Social or environmental circumstances 5% (1 month) 7.5% (3 months) 10% (6 months) 20% (1 year) |

Severe | Severe | Severe | ||||

| The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN 2015) | Not included | < 18.5 | Not included | Not included | Not included | Not included | Not included | Not included |

|

< 20 (< 70 years) < 22 (≥ 70 years) |

5% (3 months) or 10% (indefinite) |

FFMI < 15 (women) FFMI < 17 (men) |

||||||

| Cachexia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | Weight loss or BMI (kg/m2) | Biochemistry | Loss of muscle mass | Loss of muscle function | Symptoms | |||

| International Consensus Criteria (Fearon 2011) | Pre-cachexia |

≤ 5% (6 months) and Starvation absent |

Not included | Not included | Not included | Not included | ||

| Cachexia |

> 5% (6 months) or BMI < 20 and > 2% weight loss and reduced food intake Systemic inflammation |

Sarcopenia and > 2% weight loss |

||||||

| Refractory cachexia |

Variable degree of cachexia Pro-catabolic and not responsive to treatment Low performance score < 3-month Survival |

Not included |

||||||

| SCRINIO Working Group (2009) | Pre-cachexia | Asymptomatic Class 1 | > 5% of usual body weight | Not included | Not included | Not included | Absence of symptoms | |

| Symptomatic Class 2 |

Anorexia or Fatigue or Early satiety |

|||||||

| Cachexia | Asymptomatic Class 3 | > 10% of usual body weight | Not included | Not included | Not included | Absence of symptoms | ||

| Symptomatic Class 4 |

Anorexia or Fatigue or Early satiety |

|||||||

| Evans (2008) | Not included |

> 5% (12 months) Underlying chronic disease or BMI < 20 |

And 3 out of the next 5 criteria below | |||||

|

Abnormal biochemistry CRP > 5 mg/L Hb < 12 g/dL Albumin < 3.2 g/day |

Lean tissue depletion |

Decreased muscle strength | Fatigue | Anorexia | ||||

The primary objective of the study is to determine the proportion of patients with cancer seen in an outpatient supportive care clinic (SCC) at a tertiary cancer centre who screen positive for risk for malnutrition by the PG-SGA-SF, symptoms of anorexia or cachexia based on International Consensus Criteria (ICC) [7]. Secondary objectives will explore the difference in symptom burden, including depression and anxiety, and body image distress between patients with and without the ACS.

2 Methods

Patients who were potentially eligible for the study (as determined by chart screening done by research personnel) were contacted in person during their visit, over the phone, MyChart, or through any HIPAA-compliant, institutionally approved video-conferencing platform (e.g., Skype, FaceTime or Zoom).

Inclusion criteria included patients referred to the SCC for either consultation or a follow-up visit. All patients eligible must have been diagnosed with advanced cancer defined as locally advanced, recurrent/relapsed or metastatic, be able to read and speak English and must be 18 years of age or older. Exclusion criteria included patients who refused to participate in the study or noted to be cognitively impaired by the treating physician or nurse with a memorial delirium assessment scale score of ≥ 7.

The one-time, computer-assisted, self-reported survey and study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Information obtained from patients including patient's demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, height and weight) (calculated BMI [kg/m2], education level and marital status) was recorded. Weight history and date obtained during outpatient visits were recorded at the time of the survey and extracted from the electronic medical records. Weights that were obtained while patients were acutely hospitalized were excluded. Type and status of primary cancer at initial supportive care consultation was obtained, and the Zubrod performance status, a scale from 0 to 4 (0 = normal activity, 1 = symptomatic and ambulatory; cares for self, 2 = ambulatory > 50% of time; occasional assistance, 3 = ambulatory ≤ 50% of time; nursing care needed, 4 = bedridden), was recorded.

2.1 Screening for Symptom Distress

2.1.1 Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale (FAACT-A/CS) Questionnaire

The Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale (FAACT-A/CS) (4th version, Dutch) is a 12-item questionnaire scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit and 4 = very much) was completed [14]. The total score ranges from 0 to 48, whereby a lower score indicates decreased appetite, and is calculated using the FACIT manual [15]. Quality of life in the presence of anorexia and/or cancer cachexia is commonly measured in the Functional Assessment of Cancer of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT-A/CS). A FAACT-A/CS score of ≤ 32 was proposed for anorexia in patients with cancer with a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 81% [16].

2.1.2 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) consists of 14 items with 4-point numeric rating scales, including seven items on depression (HADS-D) and seven items on anxiety (HADS-A). HADS has been validated for depression and anxiety in various settings. The average Cronbach alpha for HADS-A was 0.83 and 0.82 for HADS-D. Using a cut-off of 8 or greater for either subscale, the sensitivity and specificity were both approximately 80% for both HADS-A and HADS-D [17].

2.1.3 Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS)

Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) on the day the survey was completed. The ESAS, first described in 1991, assesses common symptoms for patients receiving palliative care and has been reported to be practical, reliable and valid [18]. The ESAS yields a total score and two subscale scores: a total symptom distress score and a physical distress score (sum of 7 symptoms including pain, nausea, fatigue, sedation, appetite, dyspnoea and sleep) and psychological distress subscale (sum of 3 symptoms including depression, anxiety and feeling of well-being).

2.2 Malnutrition Screening

Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment–Short Form (PG-SGA-SF) Boxes 1–4 was completed. The PG-SGA-SF is a detailed screening tool that eliminates the physical examination, disease/condition and metabolic demand assessment components of PG-SGA but retains the medical history including weight history, food intake and nutrition impact symptoms, as well as activities and function [19]. The PG-SGA-SF has comparable sensitivity and specificity to the full-length PG-SGA [19]. The PG-SGA-SF calculates the total score of the four boxes. The higher the additive score places patients at a higher risk for developing weight loss. A PG-SGA-SF score of ≥ 6 had a high sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 77.6% in detecting malnutrition in patients with cancer seen in an outpatient clinic [20].

- How much weight have you gained or lost during the past 3 months?

- How much weight have you gained or lost during the past 6 months?

- How much weight have you gained or lost during the past 12 months?

- How much weight have you gained or lost during the past 5 years?

- Prior to your illness, what was your heaviest weight in your lifetime?

2.3 Assessment of Body Image Distress

The Body Image Scale (BIS) is a 10-item scale designed to be used in clinical trials and has been validated for assessing body image changes in cancer patients [21]. Each item will be answered as either not at all, a little, quite a bit or very much, scoring as 0, 1, 2 or 3. The higher the BIS total scores indicate dissatisfaction with appearance with a clinical cut-off ≥ 10 of 30 indicating body image dissatisfaction [22].

3 Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients. Frequency of cachexia and anorexia were estimated along with 95% confidence intervals. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared by cachexia and anorexia. The chi-squared test of Fisher's exact test was used when comparing categorical variables and the t-test or rank-sum test for continuous variables. Cohen's kappa was calculated to assess the agreement between self-report and documented history of cachexia. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP v18.0 (College Station, TX).

4 Results

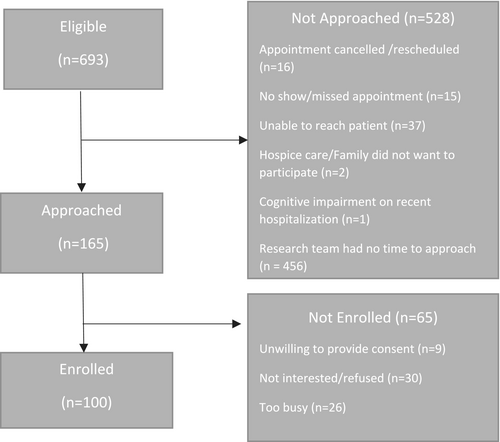

Of the 165 patients seen in an outpatient supportive care clinic who were approached, a total of 100 patients enrolled (61%). The consort diagram is outlined in Figure 1. Demographic and disease characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 2. Fifty-two per cent (52%) of participating patients were female. The mean age was 61.6 years (SD ± 11.5) for the patient population. The majority (75%) of patients were white and (82%) married. Fifty-two per cent (52%) had a college or professional school education. The mean BMI of the patient population was 26.5 kg/m2 (SD ± 6.4). The common types of advanced cancer were gastrointestinal (22%) or genitourinary (21%) with 83% of patients having metastatic disease.

| Patient characteristics | n = 100 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 61.6 (11.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 52 (52) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (4) |

| Black | 10 (10) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 11 (11) |

| White | 75 (75) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/living with partner | 82 (82) |

| Divorced/widowed | 12 (12) |

| Single/never married | 6 (6) |

| Education | |

| College graduate/professional school | 52 (52) |

| High school graduate/technical school | 41 (41) |

| Some middle/high school (Grades 6–12) | 7 (7) |

| Height, mean ± SD (cm) | 169 (10.0) |

| Weight, mean ± SD (kg) | 76.0 (20.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 ± SD | 26.5 (6.4) |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Breast | 12 (12) |

| Gastrointestinal | 22 (22) |

| Genitourinary | 21 (21) |

| Gynaecological | 8 (8) |

| Head and neck | 8 (8) |

| Haematological | 10 (10) |

| Other/unknown primary | 10 (10) |

| Thoracic | 9 (9) |

| Cancer status | |

| Metastatic | 83 (83) |

| Recurrent/relapsed | 10 (10) |

| Locally advanced | 7 (7) |

| Body Image Dissatisfaction (BIS ≥ 10) | 28 (28) |

| Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale | |

| Anxiety (total score ≥ 8) | 17 (17) |

| Depression (total score ≥ 8) | 21 (21) |

| Zubrod performance status, mean ± SD | 1.1 (1.0) |

Body image distress (BIS ≥ 10) was noted in 28% of patients, anxiety (HADS total score for anxiety ≥ 8) in 17% and depression (HADS total score for depression ≥ 8) in 21% of patients. The risk of malnutrition, as defined by a score of ≥ 6 on the PG-SGA-SF, was identified in 61% of the patient population. The percentage of 100 patients who responded yes to the following symptoms interfering with food intake in the past 2 weeks on the PG-SGA-SF include things taste funny or have no taste (31%), nausea (27%), pain (27%), fatigue (26%), constipation (23%), feeling full quickly (22%), diarrhoea (21%), dry mouth (17%), smells bother me (8%), vomiting (7%) and mouth sores (5%) and also identified heart burn (3%) stomach cramping or bloating (2%) as ‘other’ symptoms which interfere with food intake.

Table 3 reports the frequency of anorexia as defined by either an ESAS ≥ 3 or a FAACT-ACS ≤ 37 and cachexia based on various criteria. Anorexia as defined by ESAS ≥ 3 was noted in 59% of patients and by the FAACT-ACS criteria in 53% of patients. Cachexia, based on Fearon's ICC criteria, was noted in 52% of patients and the ESPEN criteria identified 15% (SD 9–25) as at risk for malnutrition. Based on changes in documented weight over time, the frequency of > 10% weight loss over a patient's lifetime, relative to usual weight or weight at diagnosis, was 61%, and > 5% weight loss over 6 months was noted in 49% of patients. Self-reported weight loss, > 10% lifetime, was noted in 62% and > 5% over 6 months in 52% of patients. Agreement was moderate between self-reported and documented weight loss over the previous 6 months ( = 0.46 [95% CI 0.28–0.63], p < 0.001) but poor between self-reported and documented > 10% lifetime weight loss ( = 0.015 [95% CI: −0.19–0.22], p < 0.8). Agreement between documented > 5% weight loss over 6 months and > 10% lifetime weight loss was also moderate ( = 0.50 [95% CI 0.33–0.67], p < 0.001).

| Assessment | Percentage % 95% CI (LL, UL) |

|---|---|

| Anorexia | |

|

ESAS ≥ 3 n = 100 |

59 (49, 69) |

|

FAACT-ACS ≤ 37 n = 100 |

53 (43, 63) |

| Malnutrition risk | |

|

PG-SGA-SF (≥ 6) n = 100 |

61 (51, 71) |

|

ESPEN criteria n = 99 |

15 (9, 24) |

| Cancer cachexia | |

|

ICC criteria n = 99 |

52 (41, 62) |

|

> 10% weight loss over lifetime n = 99 |

61 (51, 70) |

|

>5% weight loss over 6 months n = 99 |

49 (39, 60) |

|

> 10% weight loss over lifetime (self-reported) n = 96 |

62 (51, 72) |

|

> 5% weight loss over 6 months (self-reported) n = 97 |

52 (43, 63) |

Table 4 reports the relationship between symptoms of anorexia (FAACT-ACS ≤ 37) and weight loss with symptom distress in patients with cancer. Patients with symptoms of anorexia compared with no anorexia reported significantly higher total scores for anxiety (4.4 vs. 3.2, p = 0.04), depression (5.9 vs. 3.5, p = 0.001), body image distress (7.2 vs. 4.9, p = 0.03) and worse appetite as measured by the ESAS (1.4 vs. 0.6, p = 0.02). Symptom burden, including depression and anxiety, as well as body image distress were not significantly different between patients with either a history of > 10% lifetime weight loss or > 5% weight loss over 6 months. The score for PG-SGA-SF score was notably higher for patients with anorexia (9.3 vs. 4.6, p < 0.001), ≥ 10% lifetime weight loss (8.0 vs 6.3, p = 0.005) and ≥ 5% weight loss over 6 months (8.1 vs. 6.0, p = 0.01).

|

Patient characteristics N = 100 |

No anorexia n = 47 |

Anorexia n = 53 |

p |

< 10% weight loss n = 39 |

≥ 10% weight loss n = 60 |

p |

< 5% weight loss/6 months n = 50 |

≥ 5% weight loss/6 Months n = 49 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS Anxiety (mean [SD]) | 3.2 (3.2) | 4.4 (3.2) | 0.04 | 4.5 (3.8) | 3.4 (2.7) | 0.29 | 3.9 (3.6) | 3.7 (2.8) | 0.93 |

| HADS Depression | 3.5 (2.6) | 5.9 (3.8) | 0.001 | 5.1 (4.1) | 4.6 (3.1) | 0.95 | 5.1 (3.7) | 4.4 (3.3) | 0.37 |

| PG-SGA SF | 4.6 (3.3) | 9.3 (4.0) | < 0.001 | 5.6 (4/2) | 8.0 (4.3) | 0.005 | 6.0 (4.2) | 8.1 (4.4) | 0.01 |

| BIS | 4.9 (5.3) | 7.2 (6.0) | 0.03 | 6.3 (6.1) | 6.1 (5.6) | 0.99 | 6.7 (5.8) | 5.5 (5.6) | 0.36 |

| ESAS (Total Score 0–100) | 17.1 (10.8) | 31.1 (12.4) | < 0.001 | 24.0 (14.0) | 24.6 (13.3) | 0.82 | 23.0 (14.2) | 25.7 (12.7) | 0.32 |

| Pain | 1.2 (2.0) | 1.3 (2.2) | 0.91 | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.3 (2.3) | 0.80 | 1.3 (2.1) | 1.2 (2.1) | 0.57 |

| Fatigue | 1.7 (2.2) | 2.1 (2.6) | 0.55 | 1.9 (2.6) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.85 | 1.9 (2.3) | 1.9 (2.6) | 0.80 |

| Nausea | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.20 | 0.20 (1.0) | 0.13 (0.7) | 0.96 | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.61 |

| Depression | 1.0 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.9) | 0.32 | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.3 (1.8) | 0.57 | 1.2 (2.0) | 1.2 (1.7) | 0.67 |

| Anxiety | 2.2 (2.4) | 2.1 (2.3) | 0.98 | 1.9 (2.1) | 2.3 (2.5) | 0.55 | 2.0 (2.1) | 2.4 (2.5) | 0.56 |

| Drowsiness | 1.1 (2.1) | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.26 | 0.6 (1.2) | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.35 | 0.5 (1.3) | 1.3 (2.1) | 0.07 |

| Shortness of breath | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.4 (1.6) | 0.35 | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.57 | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.4 (1.7) | 0.26 |

| Sleep | 2.9 (2.6) | 2.4 (2.4) | 0.40 | 2.9 (2.6) | 2.6 (2.5) | 0.53 | 3.0 (2.6) | 2.4 (2.4) | 0.20 |

| Appetite | 0.6 (1.5) | 1.4 (2.0) | 0.02 | 0.8 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.9) | 0.33 | 1.1 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.60 |

| Feeling of wellbeing | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.0 (2.1) | 0.70 | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.2) | 0.99 | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.1 (2.0) | 0.80 |

- Note: Bolded values were significant p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: BIS = Body Image Scale, ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, FAACT-A/CS = Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PG-SGA SF = Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment–Short Form.

- a Anorexia defined by Functional Assessment of Anorexia Therapy–Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale ≤ 37; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment–Short Form; Body Image Scale; and Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale.

5 Discussion

Patients with advanced cancer evaluated in an outpatient SCC are at substantial risk for malnutrition, 61% screened positive (PG-SGA-SF ≥ 6). The subjective symptom of anorexia was prevalent in 53% of patients (FAACT-ACS ≤ 37 cut-off), and approximately 52% of patients would be diagnosed with cancer cachexia per ICC criteria. Subjective symptoms of anorexia were significantly associated with depression and anxiety (HADS) and body image distress (BIS); however, weight loss, greater than 10% (lifetime) or 5% (over 6 months), was not associated with any specific symptom burden including fatigue (ESAS), anxiety and depression or body image distress in patients with advanced cancer.

Anorexia and reduced food intake may result from physical obstruction due to the cancer mass (e.g., inability to swallow in patients with head and neck cancers), decreased central drive to eat or impaired gastric motility. Reduced food intake may also result from nutrition impact symptoms (NIS), which include dry mouth, belching, depression, constipation or diarrhoea, and pain. Increasing NIS has been associated with weight loss and decreased quality of life [23]. In our study, the subjective symptom of anorexia, but not a history of weight loss, was associated with increased psychological distress, including anxiety and depression. Anorexia, being an acute symptom may have a more direct impact on symptom burden than weight loss, which could have slowly progressed over several months, allowing patients to emotionally adapt or cope with their weight changes. Emotional distress, such as anxiety, has been significantly associated with food aversion [24], which could contribute to symptoms of anorexia. Cachexia, in our study, was not associated with emotional distress. In patients with advanced cancer, the aetiology of cachexia is often multifactorial and has been attributed to cancer and host interactions, chronic inflammation, autonomic dysfunction and hormonal changes.

In our study, the PG-SGA-SF, which was significantly associated with both anorexia and cancer cachexia, does factor NIS, which all can contribute to weight loss or risk for malnutrition. Common NIS in our patient population were altered or loss of taste (31%), nausea (27%), pain (27%), fatigue (26%), constipation (23%), early satiety (22%), diarrhoea (21%) and xerostomia (17%). Future prospective studies are needed examining NIS over time and their relationship with ACS.

Means to measure malnutrition include the PG-SGA-SF, which is quick and easy to use and assesses short-term weight history and food intake. Due to the obesity epidemic in the United States, relying on BMI might be misleading and underdiagnose malnutrition risk as well as cancer cachexia. The ESPEN criteria, which incorporates BMI, for malnutrition noted only 15% of patients. In addition, questions regarding weight loss should ideally be anchored and compared to pre-illness weight as opposed to a narrow time limit, that is, the past 6 months, to better determine the degree of weight loss and catabolic state. Recent studies show patients with pancreatic cancer had unintentional loss of adipose tissue 6 months and skeletal muscle wasting one and a half year prior to a cancer diagnosis [25]. Healthcare providers need to be aware that unintentional weight loss of adipose tissue or skeletal muscle in healthy patients may be a harbinger of underlying cancer indicating a need to monitor body composition for all patients.

In our study, the PG-SGA-SF was significantly associated with both anorexia and weight loss over 6 months and a patients' lifetime history. The PG-SGA-SF may be the ideal tool to screen for malnutrition and both anorexia and cachexia in an outpatient SCC, although currently there is no universally accepted ‘gold standard’. A recent American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) systematic review recommended, in addition to the PG-SGA-SF, five other malnutrition screening tools including Mini Nutritional Assessment, Malnutrition Screening Tool, patient-led Malnutrition Screening Tool, Nutrition/risk Screening-2002 and the NUTRISCORE [26]. These were all validated for use in outpatient settings for patients with cancer, but none in a patient population from the United States. The authors also highlight the lack of clarity of ‘routine’ screening including timing (ideally every 4–8 weeks, with additional screening during treatment, e.g., surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy) [26]. In the future, the feasibility, and benefits of screening at various time intervals in SCC should be examined.

In a study of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, the clinical assessment alone is often inadequate to identify cancer cachexia, which was noted to be 9%, but ICC criteria (> 5% weight loss over 6 months or BMI < 20 and > 2% weight loss) identified 52% of patients [27]. In our study, cachexia by ICC criteria was noted in 52% of patients and simply obtaining a history of > 10% lifetime weight loss without factoring BMI identified 61%. Both decreased BMI and loss of weight in patients with cancer have been strongly associated with poor prognosis [28]. Evans criteria [11], which factors chronic inflammation, anaemia, protein depletion, decreased food intake and muscle strength, and lean tissue depletion, were superior to ICC criteria in predicting prognosis in one study [29], indicating the weight loss alone may be not an ideal prognostic indicator. Also, in a large population of elderly patients with cancer, the PG-SGA and the PG-SGA-SF performed similarly to predict mortality but better than GLIM malnutrition criteria [30]. The PG-SGA-SF may be an ideal tool to not only screen for malnutrition and ACS but also provide prognostic information.

Anthropometrics in patients with cancer should be documented and monitored over time, but a recent study noted that BMI measurements were documented in only 55% of cases [31]. Also, the body roundness index (BRI), which incorporates the measurement of waist circumference, may also have clinical significance, and recent epidemiological study notes an elevated risk of colorectal cancer for patients with increased BRI [32]. Ideally, a more detailed assessment of body composition is needed to detect issues including sarcopenia or sarcopenic obesity, but there is no consensus on a universal measure [6]. Options include dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (considered the gold standard), cross-sectional imaging, such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging which are expensive limiting their practicality. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), which is clinically feasible in daily practice and can estimate body composition by analysing the conductance of different body tissues [6, 33]. Unfortunately, only 26 patients were able to undergo a BIA at our SCC (data not reported) due to logistical hurdles resulting from the COVID-19 epidemic. Future studies are needed to examine ways to integrate results of body composition assessments, which have no reference standards to race or ethnicity, in outpatient SCC and apply the results into clinical care.

Symptom burden can be a result of anorexia and/or cancer cachexia. The loss in muscle mass and overall change in physical appearance and physique associated with the classic ‘wasting’ of cachexia may coincide with physical symptoms such as cancer-related fatigue. In our patient population, weight loss was not strongly associated with any specific symptoms including fatigue. In patients with advanced cancer admitted to specialized home palliative care programmes, 77% of patients were malnourished, which was, on multivariate analysis, significantly associated with fatigue and anxiety [34]. Patients in an outpatient SCC, despite having a history of weight loss, may not be as functionally debilitated and burdened with symptoms of fatigue as patients at the end-of-life stage, who may be homebound or hospitalized. Future studies should prospectively evaluate changes in body composition or loss of lean body mass to determine the threshold associated with symptoms of fatigue or physical deconditioning.

Body image distress was noted to be present in 28% of the patient population. At the onset of cachexia, cancer patients may be pleased with the weight loss and report an improved body image; however, the overall response of patients to the physical manifestations of cachexia appears to be primarily negative when weight loss persists. Studies reveal that weight loss in persons with advanced cancer has been associated with body image dissatisfaction and have noted the effects of weight loss and markers of systemic inflammation on decreased overall quality of life [35-37].

Previously, the BIS has been used to assess the effect of physical changes in cancer, including in patients suffering from cachexia [21, 35]. Although the BIS has been successfully used to examine the associations between weight loss, BMI, symptom distress and overall body image, its use in cancer cachexia is complicated by a portion of the scale referring to surgical scars [21, 35]. Regardless, in a study by Rhondali et al., 39% of patients reported changes in their weight were the main reason for their change in body image [35]. However, in our patient population, the average BMI of our patient population was within normal limits (25.6 kg/m2), suggesting further weight loss later in the disease trajectory may eventually lead to body image dissatisfaction.

Emotional distress regarding lack of caloric intake is a common complaint among patients with advanced cancer [38]. Many further qualitative studies have established that psychosocial impacts resulting from cachexia are significant to patients, though most studies focus on interviews with families and caregivers [37, 39, 40]. Many patients and their families often view weight loss in advanced cancer as stressful, and they associate cachexia with poor prognosis and decreased survival [37, 39, 40]. Our study population seen in an outpatient SCC reported that despite a high proportion of patients with weight loss, psychological distress was not significantly more common. Patients with weight loss may not perceive moderate weight loss as problematic until they become less functional or exhibit signs of severe wasting.

Limitations of our study include the small sample size and the varying degrees of documentation of weight by healthcare professionals. Also, agreement was poor between self-reported and documented lifetime weight loss history of > 10% but moderate between self-reported and documented history of > 5% over 6 months, suggesting that patients may be able to recall recent weight changes better than over a longer period and more emphasis is needed on accurately measuring weight or body composition during clinical encounters. The ICC criteria for cachexia incorporates sarcopenia, the ESPEN criteria low fat-free muscle index, which were not captured by our limited assessments of body composition due to COVID-19 epidemic. In addition, lab abnormalities such as elevated C-reactive protein were not obtained. Future studies are needed to evaluate the benefits of incorporating body composition assessments and lab abnormalities in identifying malnutrition risk and ACS in patients with cancer being evaluated in outpatient SCC.

6 Conclusions

Approximately 60% of patients with advanced cancer seen in an outpatient SCC were identified at risk for malnutrition. The subjective symptom of anorexia was significantly associated with depression, anxiety and body image distress; however, the history of weight loss was not associated with any specific psychological distress or symptoms burden including fatigue. Routine screening with the PG-SGA-SF as well as documenting BMI and weight changes, comparing current weight to documented pre-illness baseline weight, should be incorporated into all outpatient visits. In an outpatient SCC, nutritional support and interventions to treat anorexia and weight loss, preferably by an interdisciplinary team, should be offered to most patients.

Author Contributions

Rony Dev: conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), formal analysis, investigation (supporting), methodology (lead), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (lead). Patricia Bramati: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Marvin Omar Delgado Guay: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), methodology (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Bryan Fellman: conceptualization (supporting), formal analysis (lead), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Ahsan Azhar: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Michael Tang: data curation (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Jegy Tennison: conceptualization (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Josue Becerra: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Sonal Admane: data curation (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Shalini Dalal: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). David Hui: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), methodology (supporting), project administration (supporting), resources (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Egidio Del Fabbro: conceptualization (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Eduardo Bruera: conceptualization (supporting), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), methodology (supporting), project administration (supporting), resources (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.