The positive significance of staged physical mental combined pain reduction nursing based on pain scoring for cancer pain patient

Xiaoqian Shao, Xuan Sun and Qiuyang Chen contributed equally to this article.

Abstract

To observe the positive of stage-based physical mental combined pain reduction nursing based on pain scoring for cancer pain patients. A total of 120 cancer pain patients admitted to our hospital from December 2022 to December 2023 were selected. They were randomly divided into a control group and an observation group, with 60 cases in each group. The control group received medication intervention nursing, whereas the observation group received phased physical mental combined pain reduction nursing. The visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores, Psychological Hope Level (HHI) score and Psychological Health Mood State Questionnaire (POMS) score of the two groups of patients were observed before nursing and at 1, 6, and 12 months after nursing. There was no difference in VAS scores between two groups at 1 month after nursing care (p > 0.05), but the observation group had lower VAS scores at 1, 6, and 12 months after nursing; In the HHI score of the observation group patients after nursing, there was no difference between the pre-nursing and 1 month post nursing scores and the control group (p > 0.05), but scores were lower than the control group at 6 and 12 months after nursing; The POMS score of the observation group patients after nursing was better than the control group. All the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Our findings suggest that staged physical mental combined pain reducing care has a positive impact on patients with cancer pain.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many people are impacted by cancer, and its prevalence is increasing as the population ages.1 A total of 18.1 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, of which 9.6 million cancer patients die across the globe, and this incidence rate will reach 29.5 million by 2040.2, 3 In 2022, the estimated number of new cancer cases in China is projected to be 4.8247 million cases, with 2.5339 million cases in males and 2.2908 million cases in females.4 Despite the absence of definitive statistical data indicating the number of patients currently suffering from cancer pain, it remains a prevalent condition accompanying the majority of cancer patients. Cancer pain is one of the common and distressing clinical symptoms of cancer patients, which brings a huge burden to the physical and mental health of patients.5 The prevalence of moderate pain or severe intensity in patients with advanced cancer is greater than 50% and is inadequately treated in approximately one third of people.6 The importance of adequate pain assessment and cancer pain complexity has long been emphasized.7 Although clinical practice guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for pain management, their adoption and adherence remain suboptimal.8 In addition, it is worth noting that pain management often takes a backseat to other cancer treatments, leading to inadequate pain treatment.9

Chronic pain remains one of the most common and disabling symptoms of cancer, although pain itself is not immediately life-threatening. Chronic pain is always associated with worse quality of life and reduced functioning because of psychological distress including fatigue and depression.10 There is some evidence that poor pain relief may reduce the survival rates of cancer.11

Effective pain management is essential to improve the quality of life of patients. With the continuous development of medical technology and a deeper understanding of the individual differences of patients, more and more studies have focused on the use of comprehensive and staged physical mental combined pain reduction nursing to relieve the pain symptoms of cancer pain patients.12-14

In this study, we will explore the positive significance of staged physical mental combined pain reduction nursing based on pain scoring for cancer pain patients. Through an in-depth analysis of the effects of this nursing on patients' pain level, physiological function, psychological state, and overall quality of life, the aim is to provide cancer pain patients with a more effective and comprehensive pain management, so as to alleviate their pain and improve their quality of life. By deeply exploring the staged physical mental combined pain reduction nursing, this article aims to provide scientific basis for medical practice, promote the application of a more individualized and comprehensive cancer pain management model, and provide cancer pain patients with more comprehensive care.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Participants and data collection

A total of 120 cancer pain patients admitted to our hospital from December 2022 to December 2023 were selected for observation. Using a random number allocation method, the patients were divided into a control group and an observation group, each consisting of 60 cases. The control group included 30 males and 30 females, with an age range of 62–97 years (mean age: 69.63 ± 5.52 years). The distribution of cancer types in the control group was as follows: 20 cases of gastric cancer, 20 cases of esophageal cancer, and 20 cases of colorectal cancer.

The observation group also comprised 30 males and 30 females, with an age range of 63–95 years (mean age: 68.45 ± 5.43 years). The distribution of cancer types in the observation group was 30 cases of gastric cancer, 10 cases of esophageal cancer, and 20 cases of colorectal cancer. There were no statistically significant differences in general patient characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05). This study has obtained ethical approval from our hospital.

2.1.1 Inclusion criteria

- Patients diagnosed with cancer and experiencing pain symptoms simultaneously.

- Patients with sufficient cognitive and communication abilities to actively participate in pain assessment and treatment.

- Patients willing and able to sign informed consent forms.

2.1.2 Exclusion criteria

- Patients with cognitive impairment, severe mental illness, or an inability to communicate effectively.

- Patients allergic to or intolerant of the physical and psychological interventions implemented in the study, such as those undergoing related treatment methods.

2.2 Assessment

The control group underwent drug intervention care, where patients were administered analgesic drugs to alleviate pain. Health education was provided, and collaboration with family members for support and encouragement was emphasized. Pain assessments were conducted, and medication adjustments were made promptly. The observation group, building upon the control group's approach, implemented a staged physical–mental combined pain reduction care based on pain scores. The specific strategies were as follows.

2.2.1 Staged physical-mental care based on pain scores

Patients with pain scores of 1–3

Emphasis was placed on prevention and early intervention. Regular pain assessments allowed early detection of patient pain, with emotional support and encouragement provided. Physical care included gentle exercise and comfortable positioning to improve blood circulation and alleviate pain transmission. Psychological interventions such as relaxation training and emotional support were incorporated. A collaborative relationship was established with patients to create personalized rehabilitation plans, including moderate exercise, a balanced diet, and sufficient rest, enhancing overall health. Patient and family education on the importance of self-pain management was integral. Although administering pain relief measures to patients, it is also crucial to accurately inform the patients and their families about the specific methods of pain alleviation. Family members play a significant role in guiding the patient to reduce the psychological burden caused by pain.

Patients with pain scores of 4–6

Care extended to address moderate pain challenges. Non-pharmacological pain relief methods, such as hot and cold compress applications, massage, and moderate exercise, were introduced. Non-opioid analgesics or mild analgesic drugs were selected to minimize potential adverse reactions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy became a more emphasized aspect of psychological care, aiming to reduce negative emotions and foster a positive attitude towards life. In this phase, the assistance of family members is particularly indispensable. When confronting the adverse reactions associated with pain and analgesic interventions, family members are required to adopt proactive psychological guidance measures to assist patients in enduring their suffering.

Patients with pain scores of 7–10

Intensive physical–mental care was implemented for patients facing severe pain. Stronger drug treatments, including analgesics and opioids, were considered, with close monitoring for potential dependency risks. Physical therapists played a crucial role in alleviating muscle tension and joint pain. Professional psychologists conducted in-depth psychological therapy to help patients cope with the psychological stress of pain.

2.2.2 Implementation of comprehensive care strategies

Effective communication channels were established to ensure comprehensive attention to patients' physiological, psychological, and social needs. Collaboration among healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, physical therapists, and psychologists, was essential. Regular team meetings and case discussions facilitated information exchange, ensuring each team member understood the patient's condition and care needs. The healthcare team remained flexible to adapt to changes in the patient's condition, adjusting care plans promptly.

2.2.3 Pain reduction care

Pain assessment

A comprehensive pain assessment was conducted before formulating pain reduction care plans. Assessment included determining the type, intensity, frequency, duration, and relationship with daily activities. The use of appropriate pain assessment tools, such as pain scoring charts, aided in objectively understanding the patient's pain condition.

Individualized treatment plans

Based on the results of pain assessment, individualized treatment plans were crucial, considering patient differences, pain type and intensity, as well as patient expectations and lifestyle. Individualized treatment plans better met unique patient needs, providing effective pain reduction.

Medication management

Medication management was the core of pain reduction care for cancer patients. Commonly used drugs included analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and antidepressants. Selection of suitable drugs was based on pain severity and individual differences. Careful assessment of patient drug tolerance and potential interactions was necessary, with personalized medication plans formulated. Monitoring patient vital signs and drug responses was essential to ensure the safety and effectiveness of pain management.

Physical therapy

Physical therapy played a crucial role in alleviating cancer pain. Methods such as massage, heat and cold therapy, traction, etc., helped relieve muscle tension, improve joint mobility, and reduce pain sensation.

Psychological support

Cancer pain not only affected the patient's body but also had negative impacts on mental health. Providing psychological support and therapy assisted patients in facing anxiety, depression, and emotional fluctuations related to pain. Psychological therapy helped patients establish positive coping strategies, enhancing their psychological resilience.

Rehabilitation care

Cancer patients may go through rehabilitation stages during treatment. The goal of rehabilitation care was to reduce pain through lifestyle adjustments, exercise, and improved nutrition. Rehabilitation care included physical therapy, rehabilitation training, dietary guidance, etc., helping patients gradually restore bodily functions and reduce pain intensity.

Regular follow-ups and adjustment of treatment plans: Pain is a dynamic process, and treatment plans need regular follow-ups and adjustments based on the patient's condition. Effective communication with patients to understand treatment effects and pain changes was crucial. Timely adjustment of medication doses and treatment plans ensured optimal pain reduction effects.

The nursing care for both groups was observed before and after 1, 6, and 12 months using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score, Hopefulness for the Future Inventory (HHI) score, and Profile of Mood States (POMS) score.

- 0 points: No pain, the patient experiences no pain.

- 1–3 points: Mild pain, slight pain that is tolerable.

- 4–6 points: Moderate pain, noticeable pain but still tolerable.

- 7–9 points: Severe pain, intense pain affecting normal activities.

- 10 points: Extreme pain, the patient experiences the most severe pain and cannot tolerate it.

- Patients typically mark their pain perception on a horizontal line, where 0 represents no pain, and 10 represents the most severe pain.

HHI score criteria includes positive attitudes toward reality and the future (T), taking positive actions (P), maintaining close relationships with others (I), with a total of 12 items. Scoring ranges from 1 to 4 points, and a higher score indicates a higher level of hopefulness.

POMS score criteria includes six dimensions: tension, anger, fatigue, depression, confusion, and vigor. A higher score indicates higher levels of tension, anger, fatigue, depression, confusion, and better vigor.

These assessments were conducted at specific intervals (before and after 1, 6, and 12 months) to evaluate the changes in VAS pain scores, HHI scores, and POMS scores, providing insights into the impact of the implemented nursing care on patients' pain perception, hopefulness, and psychological well-being. The scoring criteria for each assessment tool help quantify and analyze the observed outcomes in a systematic manner.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software. For quantitative data, paired t-tests were used and expressed as (`x ± s). For categorical data, chi-square tests were used and presented as percentages (%). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, indicating a significant difference. The choice of statistical tests and the significance threshold help ensure the rigor and reliability of the statistical analysis in evaluating the observed outcomes.

2.4 Ethics

Informed written consents were obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Comparison of VAS scores before and after nursing in two groups

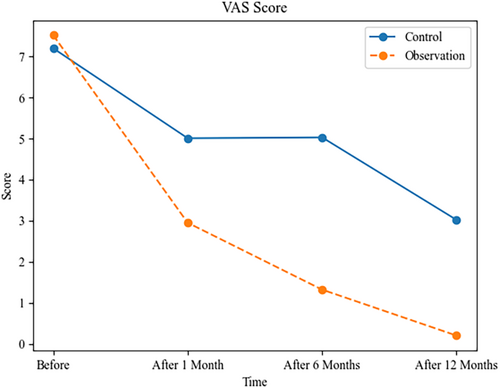

The VAS scores for the observation group's patients did not show a significant difference compared to the control group after 1 month of nursing care (p > 0.05). However, at 1, 6, and 12 months after nursing care, the VAS scores in the observation group were significantly lower, indicating a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). Refer to Table 1 and Figure 1 for detailed data and graphical representation. This suggests that the nursing interventions in the observation group contributed to a sustained reduction in pain perception over the specified time intervals compared to the control group.

| Group | Sample Size | VAS pain scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After 1 month | After 6 months | After 12 months | ||

| Control | 60 | 7.20 ± 1.32 | 5.01 ± 1.24* | 5.03 ± 0.44*, ** | 3.02 ± 0.32*, *** |

| Observation | 60 | 7.52 ± 1.41 | 2.95 ± 1.25* | 1.32 ± 0.24*, ** | 0.20 ± 0.22*, *** |

| t-Value | 1.283 | 9.063 | 57.338 | 56.250 | |

| p-Value | >.05 | <.05 | <.05 | <.05 | |

- Abbreviation: VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

- * Compared to before nursing, p < .05.

- ** Compared to after 1 month of nursing, p < .05.

- *** Compared to after 6 months of nursing, p < .05.

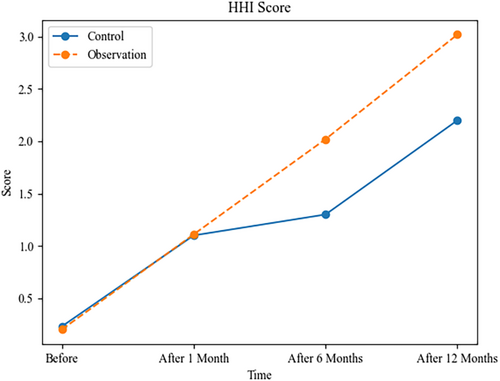

3.2 Comparison of HHI scores in two groups

After nursing care, there were no significant differences in T, P, and I scores between the observation and control groups at the pre-nursing assessments (p > 0.05). However, at 6- and 12-month post-nursing, the observation group exhibited higher scores compared to the control group, indicating a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). Refer to Table 2 and Figure 2 for detailed information.

| Group | Sample size | HHI scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After 1 month | After 6 months | After 12 months | ||

| Control | 60 | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 1.10 ± 0.20* | 1.30 ± 1.10*, ** | 2.20 ± 0.52*, *** |

| Observation | 60 | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 1.11 ± 0.21* | 2.02 ± 1.11*, ** | 3.02 ± 0.40*, *** |

| t-Value | 1.283 | 1.205 | 5.231 | 4.158 | |

| p-Value | >.05 | >.05 | <.05 | <.05 | |

- Abbreviation: HHI, hopefulness for the future inventory.

- * Compared to before nursing, p < .05.

- ** Compared to after 1 month of nursing, p < .05;

- *** Compared to after 6 months of nursing, p < .05.

The POMS (Profile of Mood States) scores for the observation group post-nursing were significantly better than those for the control group, with statistical significance (p < 0.05). Refer to Table 3 for detailed information.

| Group | Sample Size | Tension | Anger | Fatigue | Depression | Vigor | Confusion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||

| Control | 60 | 21.20 ± 3.02 | 14.82 ± 1.20 | 18.45 ± 3.52 | 12.02 ± 3.52 | 13.25 ± 3.20 | 12.36 ± 2.20 | 31.25 ± 4.12 | 20.33 ± 3.24 | 6.42 ± 2.32 | 11.20 ± 3.20 | 12.52 ± 2.52 | 8.78 ± 2.30 |

| Observation | 60 | 21.22 ± 3.20 | 11.15 ± 1.02 | 18.41 ± 3.33 | 8.25 ± 3.10 | 13.20 ± 3.41 | 8.36 ± 2.21 | 30.20 ± 4.10 | 15.48 ± 3.23 | 6.30 ± 3.52 | 15.42 ± 3.52 | 12.54 ± 2.31 | 6.13 ± 1.52 |

| t-Value | 0.563 | 8.623 | 0.581 | 9.263 | 0.451 | 8.752 | 0.362 | 10.236 | 0.364 | 83.461 | 0.752 | 7.468 | |

| p-Value | .821 | <.05 | .487 | <.05 | .871 | <.05 | .461 | <.05 | .5323 | <.05 | .365 | <.05 | |

4 DISCUSSION

Cancer pain is a persistent and complex pain caused by cancer.15 It may be caused by the tumor directly affecting the body tissues, nerves, and organs, or it may be an indirect effect of the treatment process such as surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.16 Cancer pain has a significant physical and psychological impact on patients, so effective nursing is essential. The goal of cancer pain nursing is to improve the quality of life of patients, relieve their pain, improve comfort, and promote rehabilitation. Good nursing care helps to relieve pain symptoms, massage therapy for example,17 maintain patients' physical function, promote treatment effects, and reduce patients' concerns about treatment, thereby promoting their better adherence to the treatment plan.18

Staged physical mental combined nursing based on pain score is a comprehensive nursing method that takes corresponding physical and mental nursing measures for different stages based on the pain level of patients. This model of nursing aims to provide a personalized and progressive care program based on the patient's pain score, focusing on both the physiological aspects of pain and the patient's psychological and emotional needs.19 Pain relief nursing refers to reducing or relieving the pain experience of patients through various means and methods. For patients with cancer pain, pain relief nursing is crucial, because cancer pain is often one of the serious problems faced by patients.20

Cancer pain management is a multimodal and individualized approach. The WHO analgesic ladder serves as a guide, starting with non-opioids for mild pain, progressing to weak opioids for moderate pain, and strong opioids for severe pain. Adjuvant medications may be used to address specific pain syndromes. Interventional techniques like nerve blocks and epidural analgesia provide targeted relief. Psychological support and interdisciplinary teams enhance overall pain control, addressing emotional and physical needs. Regular pain assessments guide treatment adjustments to optimize pain relief and quality of life.21, 22

Through effective pain relief nursing, the following aspects can be achieved, so as to improve the pain score, HHI score and POMS score of cancer pain patients. First, pain relief nursing helps to reduce the pain score. Reasonable drug therapy, physical therapy and other pain management methods can effectively relieve the pain of patients and make them more comfortable in daily life.23

What's more, pain relief nursing can improve the psychological hope level of patients. Through effective pain relief, patients not only gain physical comfort but also establish a more optimistic attitude psychologically. Reducing pain improved the overall well-being of patients, increased their confidence in treatment, and prompted a more positive approach to the disease.24, 25 This comprehensive pain relief nursing not only helps to improve the pain score but also has a positive impact on the psychological hope level and mental health state of patients, bringing them a more comprehensive rehabilitation experience. Cancer pain is often accompanied by anxiety, depression and other psychological problems, and effective pain relief nursing can not only relieve the psychological burden caused by pain but also improve the mental health level of patients through psychological support, psychological counseling and other means, so as to affect the POMS score.26, 27

In general, through staged physical mental combined nursing based on pain score, providing customized pain reduction nursing plan for individual differences of cancer pain patients not only helps to improve the pain experience of patients but also positively affects their mental health status. This comprehensive nursing model provides comprehensive and personalized care for patients with cancer pain, which helps to improve their quality of life and enhance their confidence in fighting cancer.

4.1 Limitations

The main strength of our study is the findings which, combined with results from prior research, presents implications with potentially high clinical value for patients treated with cancer pain. Our study is not without limitations. First, it is imperative to acknowledge that this investigation is a single-center study, inherently limiting its generalizability. The sample size is notably small and heterogeneous, comprising patients with varying demographics, comorbidities, and baseline characteristics. This heterogeneity poses a challenge in disentangling the specific effects of the procedure under investigation from the confounding influence of these pre-existing factors. Consequently, the findings may be skewed by unrecognized biases and may not accurately reflect the true nature of the procedure's outcomes in a broader, more diverse patient population. Moreover, the dearth of data in this study underscores a critical limitation. The scarcity of information could potentially obscure the true impact of the procedure, as the results may merely mirror preexisting conditions or external factors unrelated to the procedural aftermaths. This limitation underscores the need for larger, multicenter studies to accumulate sufficient statistical power and robustly assess the procedure's effectiveness while mitigating the influence of confounding variables. Furthermore, the absence of raw data from the reference study on cancer pain represents a potential source of bias. Without direct access to the primary, unprocessed data, it becomes difficult to compare and contrast the results of the current study with the established literature. This gap in information could lead to misinterpretation or inaccurate conclusions, as the analysis may be based on secondary, potentially misrepresented or aggregated data. Therefore, it is essential to strive for direct access to the original data whenever possible to ensure the validity and reliability of comparisons and conclusions drawn from this study. In summary, although the study provides valuable insights, its single-center design, small and heterogeneous sample, lack of data, and unavailability of raw data from the reference study on cancer pain all contribute to significant limitations that must be carefully considered when interpreting its results. Future research endeavors should aim to address these limitations by conducting larger, multicenter studies with more representative and homogeneous samples, while ensuring access to comprehensive and unadulterated data sources.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Xueqin Lv.; methodology, Xuan Sun.; software, Xuan Sun. and Qiuyang Chen.; validation, Xiaoqian Shao. and Qiuyang Chen.; formal analysis, Lingyun Shi.; investigation, Lingyun Shi and Yeping Wang; resources, Sun Xuan; data curation, Yeping Wang.; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoqian Shao and Xuan Sun.; writing—review and editing, Qiuyang Chen and Xueqin Lv.; visualization, Lingyun Shi.; supervision, Xueqing Lv.; project administration, Xueqing Lv.; funding acquisition, Xueqing Lv. and Xiaoqian Shao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The research was funded by Research Project of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital (No. ZH202110) and thanks for Cai Hongzhou's guidance and coordination.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.