Health-related quality scores in childhood interstitial lung disease: Good agreement between patient and caregiver reports

Abstract

Introduction

Childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD) is a heterogeneous group of mostly chronic respiratory disorders. Assessment of health-related quality of life (HrQoL) in chILD has become increasingly important in clinical care and research. The aim of this study was to assess differences between patient-reported (self) and caregiver-reported (proxy) HrQoL scores.

Methods

This study used data obtained from the chILD-EU Register. After inclusion (baseline), the patient's health status was followed up at predefined study visits. At each study visit, caregivers and patients were handed validated, age-specific HrQoL questionnaires. HrQoL data entered at baseline were used to compare self- and proxy-reported HrQoL scores. For the longitudinal analysis, we compared HrQoL scores between the baseline and the next follow-up visit.

Results

No differences between patient- and caregiver-reported HrQoL scores were found for school functioning, chILD-specific questionnaire score, and physical health summary score. Self-reported HrQoL scores were higher for the subscales emotional functioning (77.4 vs. 70.7; p < .001), social functioning (81.9 vs. 76.2; p < .001), as well as psycho-social summary score (76.5 vs. 71.8; p < .001) and total score (74.7 vs. 70.8; <.001). The longitudinal analysis showed that a significant change in a patient-reported HrQoL score resulted in a significant change in a caregiver-reported HrQoL score after a mean time of 11.0 months (SD 9.4).

Conclusions

We found a good agreement between children- and caregiver-related HrQoL scores. In chILD, caregivers are able to sense changes in children's HrQoL scores over time and may be used as a proxy for children unable to complete HrQoL questionnaires.

1 INTRODUCTION

Childhood interstitial lung diseases (chILD) are a heterogeneous group of rare and chronic respiratory disorders that mainly affect the lung parenchyma and gas exchange.1 Disease management is both challenging and lifelong. Treatment options are limited and differ depending on the underlying cause.2 Earlier studies have reported that clinicians have limited abilities to judge patients' health-related quality of life (HrQoL)3 and that patient-reported outcomes (PROs) often provide a superior understanding of the patient's perspectives regarding treatment benefits as well as health status.4 Therefore, the assessment of HrQoL has emerged as a powerful method of monitoring clinical courses, evaluating treatment outcomes, and identifying patients at risk for adjustment problems.5-7 Most questionnaires assess different domains like physical, emotional, and social function. The multidimensional construct helps assess components of well-being. Indeed, HrQoL scores yield a more comprehensive description of the medical condition than the sole reporting of clinical symptoms8 and are therefore frequently used for monitoring the patients' subjective health status and as outcome parameters in clinical trials.9-11

For children with chronic diseases, HrQoL scores can be challenging to assess as the patients might be too young or too sick to complete the questionnaires, and there is an ongoing debate whether proxy ratings can be considered an adequate substitute for the children's own ratings.5 Different studies assessed the relationship between children's and caregivers' HrQoL scores. Most commonly, the relationship was studied using Pearson's correlations as a statistical method, a major advantage of which is the simplicity of use. However, some authors claim this method to be insufficient as correlations reflect a direct conjunction, but do not assure that HrQoL scores are interchangeable.12 Some authors prefer to focus on the degree of difference between raters. The variability is determined by multiple t-tests for the different domains.13, 14 The advantage of this method is that it provides differences in HrQoL scores between children and proxies. However, using this method, a minimal difference with no clinical relevance can be statistically proven by increasing the number of participants. A way to overcome this methodological issue may be to assess the change of pairs of children and their proxies repetitively. To our knowledge, there have been no prior attempts to assess differences in HrQoL scores between children and caregivers longitudinally.

The aim of this study was to analyze the level of agreement between children and their caregivers regarding the different dimensions of HrQoL. Children with chronic impairment are under careful surveillance by their caregivers, so we suspected a good agreement between caregivers' and patients' HrQoL scores.

2 METHODS

2.1 chILD EU Register and study design

This study used data obtained from the chILD-EU Register (www.childeu.net). It is an observational, web-based management platform that prospectively collects clinical data of children diagnosed with chILD. Local physicians participated as referring centers after all necessary contractual, legal, and ethical requirements had been fulfilled. Each patient and/or caregiver gave age-appropriate assent and written informed consent. Following inclusion (baseline visit), completeness of data was checked, and in a multidisciplinary team meeting, the diagnosis was made in accordance with the clinical guidelines of the American Thoracic Society15 and the European management platform for interstitial lung diseases in children.16 Following this expert review process, data about the clinical course of the patients were prospectively collected at predefined visits and entered by participating centers. After inclusion (baseline), the patients were followed up at defined study visits. The implementation and use of the chILD EU Register have been described in detail elsewhere.16

2.2 Health-related quality of life

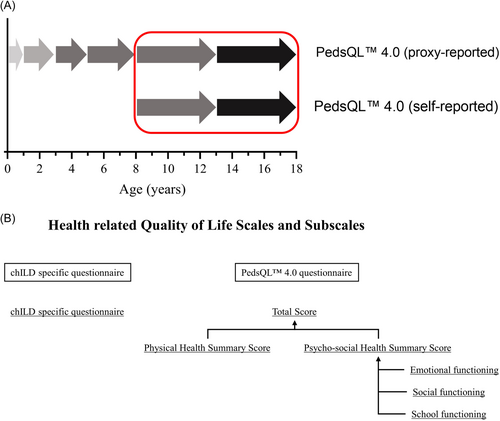

At every visit, the caregivers and patients were handed PROs, which were filled out separately by the patients (self-reported) and caregivers (proxy-reported). The questionnaires included the chILD-specific questionnaire and the generic pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL™ 4.0) questionnaire. Proxy-reported, age-specific questionnaires were available for the age groups: 0–12 months, 13–24 months, 2–3 years, 4–7 years, 8–13 years, and 14–17 years. Self-reported, age-specific questionnaires were available for the age groups: 8–13 and 14–17 years. There are no validated self-reported questionnaires for children under the age of 8 years available. In this study, HrQoL scores between caregivers and children at least 8 years of age were compared (Figure 1A). PROs were available in German, English, Turkish, Polish, Italian, Hungarian, Danish, Greece, and Spanish. HrQoL data entered at baseline were used to compare self- and proxy-reported HrQoL scores.

The generic PedsQL™ 4.0 questionnaire consisted of the two major scales: Physical health summary score and psycho-social health summary score, which may be combined to the total score. The psycho-social health summary score was composed of the subscales of emotional functioning, social functioning, and school functioning (Figure 1B). Each subscale consisted of multiple items assessing different sections of everyday life. For each item, a 5-point response scale was utilized (0 = never a problem; 1 = almost never a problem; 2 = sometimes a problem; 3 = often a problem; 4 = almost always a problem). The items were linearly transformed to a 0−100 point scale. Higher scores indicated better HrQoL. Feasibility, reliability, and validity as well as internal consistency for chILD specific questionnaire and generic PedsQL™ 4.0 questionnaire were reported before.9 HrQoL scores provided by patients (self-reported) and their caregivers (proxy-reported) were compared.

In addition, a longitudinal analysis was performed to evaluate the concordance between self- and proxy-reported HrQoL scores over time. First, the change in HrQoL scores between baseline and follow-up visits, as reported by the patients, was calculated. As absolute changes in patient-reported HrQoL scores of ∆5.0 was considered significant,17 each patient was allocated into one of the following groups: Group 1 (deteriorated HrQoL score) ∆HrQoL score ≤ −5.0, Group 2 (unchanged HrQoL score) −5.0 < ∆HrQoL score < 5.0, and Group 3 (improved HrQoL score) ∆HrQoL score ≥5.0. Next, for each patient-reported HrQoL score, the corresponding caregiver-reported HrQoL score was calculated.

2.3 Statistics

The statistical evaluation of the data was done with SPSS software for statistical analyses (Version 26.0) and GraphPad Prism (Version 8.4.3). Demographic data and sample characteristics were reported as means (standard deviations [SD]) or numbers (percent). Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution (Kolmogorov−Smirnov test), and differences between groups were analyzed using paired sample t-test or Wilcoxon sum rank test, as appropriate. The correlation between different variables was calculated using Spearman's correlation (two continual variables) or Eta (η) correlation (continual and nominal variables).

3 RESULTS

A total of 31 centers from nine different countries participated in this study that was conducted over a 10-year period between 2014 and 2023. During this time, 319 children with chILD and older than 8 years of age were included in the data platform of the Kids Lung Register by the participating centers. A total of 105 patients were excluded because of misdiagnosis/no diagnosis (n = 33) or no recorded HrQoL data (n = 72). HrQoL data were available from 214 patients. Males (52.8%) and females (47.2%) were almost equally distributed. Most patients were treated in Germany (55.1%), the UK (14.0%), Turkey (12.6%), Poland (7.9%), and Italy (5.6%). The spectrum of chILD categories and subcategories observed was broad. Characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1. Patients included in this study were older than patients with no HrQoL data recorded (12.8 [SD 3.9] vs. 11.3 [SD 3.1] years; p < .001). No differences were found regarding the distribution of diagnoses (p = .085; χ2) or sex (p = .066; χ2).

| Study cohort | |

|---|---|

| Total sample size | 214 |

| Age (years) | 12.9 (3.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 113 (52.8%) |

| Female | 101 (47.2%) |

| Caregiver completing the questionnaire | |

| Mother | 153 (71.5%) |

| Father | 56 (26.2%) |

| Foster parent | 5 (2.3%) |

| The country the patient was treated in | |

| Germany | 118 (55.1%) |

| UK | 30 (14.0%) |

| Turkey | 27 (12.6%) |

| Poland | 17 (7.9%) |

| Italy | 12 (5.6%) |

| Othera | 10 (4.7%) |

| Disease category | |

| A1 - DPLD-diffuse developmental disorders | 3 (1.4%) |

| A2 - DPLD-growth abnormalities deficient alveolarization | 7 (3.3%) |

| A3 - DPLD-infant conditions of undefined etiology | 28 (13.1%) |

| A4 - DPLD-related to alveolar surfactant region | 45 (21.0%) |

| B1 - DPLD-related to systemic disease processes | 45 (21.0%) |

| B2 - DPLD-in the presumed immune intact host related to exposures | 36 16.8%) |

| B3 - DPLD-in the immunocompromised host or transplanted | 8 (3.7%) |

| B4 - DPLD-related to lung vessels' structural processes | 22 (10.3%) |

| B5 - DPLD-related to reactive lymphoid lesions | 3 (1.4%) |

| Bx - DPLD-unclear RDS in the non-neonate | 4 (1.9%) |

| By - DPLD-unclear non-neonate | 3 (1.4%) |

- Note: Data are presented as numbers (%) or mean (standard deviation).

- a Hungary 4 (1.9%), Denmark 3 (1.4%), Greece 2 (0.9%), and Spain 1 (0.5%)

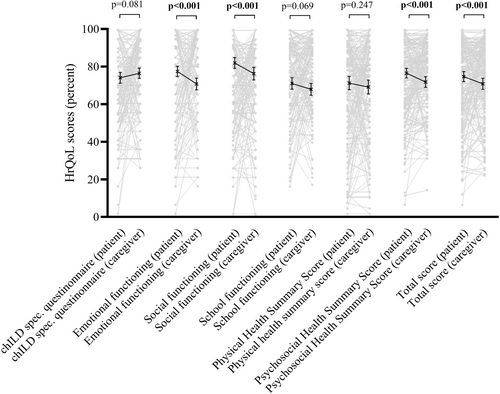

At baseline, correlation analysis between patient- and caregiver-reported HrQoL scores revealed a moderate to strong correlation for all scales (Table 2). Patient-reported HrQoL scores were higher than caregiver-reported scores for psycho-social summary score (76.5 [SD 18.5] vs. 71.8 [SD 20.8]; p < .001) and the total score (74.7 [20.0] vs. 70.8 [22.0]; <0.001), as well as the subscales emotional functioning (77.4 [SD 20.1] vs. 70.7 [SD 23.1]; p < .001) and social functioning (81.9 [SD 21.1] vs. 76.2 [SD 24.8]; p < .001) (Table 3 and Figure 2). No differences between patient- and caregiver-reported HrQoL scores were found for school functioning (71.0 [SD 22.5] vs. 67.9 [SD 22.9]; p = .069), chILD specific questionnaire score (74.1 [SD 20.5] vs. 76.5 [SD 19.4]; p = .081), and physical health summary score (71.2 [SD 26.1] vs. 69.1 [SD 27.3]; p = .247) (Table 3 and Figure 2). The fact that a caregiver (mother, father, foster parent) completed the questionnaire had only a small effect for all dimensions: chILD specific questionnaire (η2 0.03), emotional functioning (η2 0.04), social functioning (η2 0.07), school functioning (η2 0.05), physical health summary score (η2 0.04), psycho-social health summary score (η2 0.07), and total score (η2 0.06). In a subanalysis, differences between patients' and caregivers' HrQoL scores were found only for the age group of children below 13 years but not in the age group of 13 years and older (Supporting Information S1: Table 1a/b).

| Health related quality of life dimensions | Spearman's correlation coefficient (p-value) |

|---|---|

| chILD specific questionnaire | 0.40 (p < .001) |

| Emotional functioning | 0.41 (p < .001) |

| Social functioning | 0.54 (p < .001) |

| School functioning | 0.51 (p < .001) |

| Physical health summary score | 0.51 (p < .001) |

| Psycho-social health summary score | 0.55 (p < .001) |

| Total score | 0.55 (p < .001) |

- Abbreviation: chILD, childhood interstitial lung disease.

| Patient-reported health related quality of life score | Caregiver-reported health related quality of life score | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| chILD specific questionnaire | 74.1 (20.5) | 76.5 (19.4) | .081 |

| Emotional functioning | 77.4 (20.1) | 70.7 (23.1) | <.001 |

| Social functioning | 81.9 (21.1) | 76.2 (24.8) | <.001 |

| School functioning | 71.0 (22.5) | 67.9 (22.9) | .069 |

| Physical health summary score | 71.2 (26.1) | 69.1 (27.3) | .247 |

| Psycho-social health summary score | 76.5 (18.5) | 71.8 (20.8) | <.001 |

| Total score | 74.7 (20.0) | 70.8 (22.0) | <.001 |

- Note: Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), and differences between groups were analyzed using paired sample t-test or Wilcoxon sum rank test, as appropriate.

- Abbreviation: chILD, childhood interstitial lung disease.

A total of 121 patients provided follow-up data after a mean time of 11.0 months (SD 9.4). Results of the responsiveness analysis revealed a good agreement between patient- and caregiver-reported changes in HrQoL scores. A change of patient reported HrQoL scores above |5.0| between two visits resulted in change of caregiver-reported HrQoL scores above the corresponding minimal important differences (MIDs).17 In contrast to that, smaller changes of patient-reported HrQoL scores revealed no meaningful changes in caregiver-reported HrQoL scores (Table 4). A significant change in a patient-reported HrQoL score resulted in a significant change in a caregiver-reported HrQoL score.

| Group 1 (deteriorated HrQoL score) ∆ health related quality of life score ≤−5.0 | Group 2 (unchanged HrQoL score) −5.0 < ∆ health related quality of life score <5.0 | Group 3 (improved HrQoL score) ∆ health related quality of life score ≥5.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ chILD specific questionnaire | −4.7 (14.0) | 1.6 (11.9) | 4.8 (15.8) |

| ∆ Emotional functioning | −4.7 (16.9) | 2.2 (17.3) | 8.5 (20.7) |

| ∆ Social functioning | −4.7 (17.3) | 2.0 (17.7) | 5.9 (21.1) |

| ∆ School functioning | −7.9 (23.1) | 1.1 (22.4) | 9.2 (21.7) |

| ∆ Physical health summary score | −5.0 (20.1) | 0.5 (17.9) | 5.6 (16.4) |

| ∆ Psycho-social health summary score | −6.1 (19.0) | 0.5 (18.0) | 5.8 (20.6) |

| ∆ Total score | −6.9 (14.4) | 1.6 (15.1) | 8.8 (16.6) |

- Abbreviations: chILD, childhood interstitial lung disease; HrQoL, health-related quality of life.

- The table shows the caregiver-reported change of HrQoL in relation to the patient-reported HrQoL.

- First, the change in HrQoL scores between baseline and follow-up visits, as reported by the patients, was calculated. As absolute patient-reported HrQoL score change of ∆5.0 is considered significant,17 each patient was allocated into one of the following groups: Group 1 (deteriorated HrQoL score) ∆HrQoL score ≤ −5.0, Group 2 (unchanged HrQoL score) −5.0 < ∆HrQoL score < 5.0, and Group 3 (improved HrQoL score) ∆HrQoL score ≥5.0. Finally, for each patient-reported HrQoL score, the corresponding caregiver-reported HrQoL score was calculated. The table displays the corresponding means (standard deviation) of the HrQoL scores as reported by the caregivers.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first study to compare patient- and caregiver-reported HrQoL scores for a large cohort of children diagnosed with chILD. We found good agreement between self- and proxy-reported HrQoL scores reflecting physical activity or functioning (chILD-specific questionnaire and physical health summary score) but lower agreement reflecting emotional or social domains (emotional functioning, social functioning, and psycho-social health summary score). The differences in the psycho-social subscales found in this analysis can be considered clinically relevant as the difference in the HrQoL scores was above the previously reported MIDs in chILD.17 MIDs reflect the smallest change in a parameter that is considered to have a clinical impact or prompting a potential change in treatment.18-21

Previous studies showed that the level of agreement is dependent upon the health domain being examined. Inferior concordance between HrQoL scores reported by patients and their caregivers reflecting psycho-social rather than physical domains have been described before.22-26 It is unclear whether these discrepancies may reflect real differences in perspectives or lack of insight into the children's lives.27 Caregivers may perceive psycho-social issues to have a more negative impact on the children's well-being than the children themselves do.5, 28 Some authors argue that caregivers are better able to judge physical rather than psycho-social domains as the former can be observed directly.29 Others argue that discrepancies reflect a lack of insight into the children's lives.30, 31 A lower level of agreement is plausible with respect to activities like psycho-social interaction that exist outside the home. Interestingly, the post-hoc analysis of our data revealed that differences in HrQoL scores for psycho-social domains were only present in children below 13 years of age but not in the older age group. One may speculate that greater verbal skills in adolescents may facilitate abilities to express feeling to their caregivers, leading to better concordance in their respective evaluations.5 Consequently, for patients between 8 and 13 years of age, self- and proxy-reported HrQoL questionnaires may be seen as complementary and should therefore be filled out by both.

In the longitudinal analysis, there was a good agreement between the caregiver- and patient-reported changes in HrQoL scores for all assessed scales and subscales. This finding suggests that caregivers are susceptible to children's HrQoL variations for all dimensions. HrQoL scores provided by caregivers are a useful tool to monitor disease progression and may be used to assess treatment responses in children not capable of completing HrQoL questionnaires themselves. For chronically-affected children, it is not clear in what time period HrQoL questionnaires should be handed out to the patients and their caregivers. One might argue that HrQoL reports are complementary to the assessment of clinical symptoms used for monitoring the patient's medical condition, and HrQoL questionnaires should, therefore, be filled out depending on the medical condition at the respective routine clinical visit.

There are some limitations to interpreting our findings. In chILD, there exist no validated self-reported HrQoL questionnaires for children under the age of 8 years. Children at that age usually lack the linguistic and cognitive skills required for understanding and responding to the questions in the questionnaire.5 Also, although the questionnaires were usually returned during the clinical visit, we did not collect data proving that the PROs were not filled out at another place or at a later time point. An earlier report found that HrQoL score agreement between children and caregivers was higher when the questionnaires were completed at home.32 Furthermore, this was not a population-based study and we did not monitor compliance to fill out HrQoL questionnaires. HrQoL data of some patients may also be missing because the questionnaires were not handed out by the centers, not completed by the caregivers, or the data was not entered into the Kids Lung Register. Patients with no HrQoL data were significantly younger than children with a complete data set. It might be that some of the data is missing because completing the HrQoL questionnaire constituted too much of a challenge for some young children with a chronic respiratory condition. However, the distribution of diagnoses was not different between patients included and not included in the study. Finally, we were not able to include a cohort large enough to create a robust statistical model to assess how the level of agreement between self- and proxy-reported HrQoL scores may be influenced by the level of physical activity.

In summary, we found a good agreement between children's and caregivers' HrQoL scores. In chILD, caregivers are able to sense changes in children's HrQoL scores over time and may thus be used as proxies for children unable to complete the HrQoL questionnaire.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elias Seidl developed the theoretical framework, processed the analytic calculations, performed the data interpretation, and took the lead in writing the manuscript. Matthias Griese organized the project and the platform, as well as contributed to the manuscript providing critical feedback. Clinical principal site investigators of the project were Elias Seidl, Matthias Griese, Nicolaus Schwerk, Julia Carlens, Martin Wetzke, Nural Kiper, Nagehan Emiralioglu, Honorata Marczak, Joanna Lange, Katarzyna Krenke, Nicola Ullmann, Dora Krikovszky, Susanne Hämmerling, and Holger Köster. All participating centers contributing less than 2% of the analyzed data were listed under the chILD-EU collaborator's group, which is included as a contributing author.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the European Register and Biobank on Childhood Interstitial Lung Diseases (chILD-EU register), which was funded by the European Commission under FP7-HEALTH-2012-INNOVATION-1, HEALTH.2012.2.4.4-2: Observational trials in rare diseases. M. G. is supported by DFG (Gr 970/9-2), FP7 Coordination of Non-Community Research Programmes (305653-chILD-EU), Cost CA (16125 ENTeR-chILD), and European Respiratory Society Clinical Research Collaboration (CRC).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest

ETHICS STATEMENT

All caregivers of the patients provided written informed consent and the participants' verbal assent to participate in the chILD EU Register. The responsible lead ethics board, the Ethical Review Committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich, Germany (EK 026-06, 257-10, 111-13, 20-329) approved the register and the data analysis for this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.