The impact of cancer on the mental health of patients parenting minor children: A systematic review of quantitative evidence

Abstract

Objective

To provide an overview of quantitative data on the impact of cancer on the mental health of patients parenting minor children. We focused on mental health outcomes, their levels and prevalence, and applied measurement tools.

Methods

MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Web of Science were searched up to March 2021. We included quantitative studies, published in a peer-reviewed journal and reporting outcomes on the mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety) of cancer patients parenting minor children (≤ 21 years). Study quality was assessed based on the National Institute for Health assessment tool for observational studies. This study is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019141954).

Results

A total of 54 articles based on 36 different studies were included in this systematic review. Studies differ markedly regarding study and sample characteristics (e.g., outcome measures, sample size, parental health status). Depression and anxiety levels range from normal to abnormal, according to applied measurement tools. 7%–83% of parents with cancer have depression scores indicating probable depression and 19%–88% have anxiety scores indicating anxiety disorder.

Conclusions

This review reveals the dimension of mental burden affecting cancer patients parenting minor children. To identify, address and timely treat potentially arising mental health problems and support needs, affected parents should be closely monitored by healthcare professionals and referred to specialized support offers, if necessary. In the context of a comprehensive patient- and family-oriented care, it is highly relevant to integrate mental health (including parental) issues routinely into oncological care by proactively asking for the patient's psychosocial situation and the family status.

1 BACKGROUND

A cancer disease is not only associated with physical but also with mental burden.1 Prevalence studies on mental burden reveal that between 35% and 52% of cancer patients experience elevated or even high levels of distress.2, 3 In a large sample of cancer patients, the prevalence for any mental disorder was 32%, reporting highest rates for any mental disorder in breast cancer patients (42%).4 Furthermore, study results indicate that mental burden in cancer patients may be modulated by parenthood: comparing the levels of mental burden in cancer patients with and without minor children resulted in significantly higher depression and anxiety rates for parents of minor children.5 According to findings of a systematic review (based on data from Germany, Norway, Japan and USA), a substantial proportion of cancer patients (14%–25%) are parents of minor children (≤ 25 years).6 In addition to disease related burden, cancer patients with minor children are affected by parenting issues as well, such as concerns and worries about the impact of the disease on their children and uncertainties regarding how to communicate and inform children about the disease.7 Affected parents experience sudden disruptions of daily lives, role changes within the family and the need to adjust life plans according to the new situation.8 Balancing out one's own role as a patient and as a parent might be one major challenge of affected parents, as patient needs may counteract with the parental role. Due to parental concerns of not being able to address the children's needs sufficiently, feelings of guilt, insufficiency and loss of control may arise.7 Results of a study by Inhestern and colleagues (2016) indicate that affected parents experience mental burden not only in times of diagnosis and its treatment, but also up to six years after the diagnosis.9 Cancer and its side effects are stressors that may not only affect the patient him- or herself, but also his or her family, including the children.10 Findings of a systematic review indicate that most children of early-stage cancer patients do not experience severe psychosocial difficulties.11 Nevertheless, they are at a slightly increased risk to develop internalizing problems (e.g., sleep problems, somatic complaints, anxieties).11 While having an ill mother or a depressed parent is associated with a worse psychosocial adjustment of the children (e.g. more internalizing or externalizing problems), studies found an association between good family functioning (e.g., expression of feelings, open communication) and better adjustment of the children.12, 13 Distress in mothers is especially negatively associated with the mental health of their adolescent daughters.14 Regardless of a cancer diagnosis, the parental mental health status is associated with the children's mental health. One study was found that about 40% of children with severely depressed parents develop a psychiatric disorder before the age of 20.15 Hence, screening of the parental mental health status in routine cancer care is not only relevant for identifying and ideally addressing parental burden, but also for detecting family support needs and to prevent negative long-term effects in the children.

-

Which outcome parameters and measurement tools are mainly applied in current research to assess the impact of cancer on the mental health of patients parenting minor and young adult children?

-

What levels and prevalence rates of mental burden (e.g., depression, anxiety, quality of life (QoL) and parenting issues) are reported in cancer patients parenting minor and young adult children?

2 METHODS

The reporting of this systematic review follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guideline.19 A review protocol was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD 42019141954).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria (IC) were specified in advance and documented in the review protocol. Studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: quantitative study design (IC1), explicitly collecting data on cancer patients (IC2) with at least one minor or young adult child (≤ 21 years) (IC3), assessing levels and/or prevalence rates of mental burden (IC4), published in a peer-reviewed journal (IC5), written in English or German (IC6) and accessible full text (IC7). Publications were excluded if no data was collected on the impact of cancer on parental mental health, if the patient's youngest child was older than 21, or if no information on the children's age was given.

2.2 Database search

We searched the following databases up to 26 March 2021: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Web of Science. We did not limit the search according to the year of publication. Key terms for the search strategy were developed in cooperation with a librarian of the local academic library of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. The list of search terms included the following key terms: (cancer OR neoplasm*) AND (parent* OR mother OR father) AND (burden OR stress* OR strain OR distress OR “quality of life” OR depress* OR anxiety). Terms like NOT (pediatric OR “childhood cancer” OR qualitative [Title]) were used to exclude studies on childhood cancer as well as exclusively qualitative studies (see supplemental Material S1 for an exemplary search strategy). To identify further relevant studies, we conducted backward citation.

2.3 Study selection

One author (LJ) screened titles and abstracts of all identified records. For full text screening, we developed a checklist of predefined criteria. This checklist was previously piloted by three independent raters to identify any ambiguities or different interpretations using 10 exemplary publications. The raters' feedback gave no reason for adjusting the checklist. Next, two researchers (LJ, MB) independently screened full-text articles using the developed checklist. In case of disagreement, consensus was reached on inclusion or exclusion by discussion and if necessary, by consulting a third researcher (LI).

2.4 Data extraction, data synthesis and quality assessment

Data from included publications was extracted independently by two researchers (LJ, MB) using a developed data extraction form. We collected data on study characteristics (e.g., country of study conduct, sample size, children's age, gender distribution), investigated mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety), measurement tools (e.g., HADS, PCQ) and results on the level of impact (M, SD) and on the prevalence (in %). In case of longitudinal interventional study designs, we only included pre-intervention data for synthesis. In case of reported data on the patient's QoL using measures comprising more than the mental health impact, we only included data on mental health outcomes (e.g., the mental health component of the SF-8). Two researchers (LJ, MB) assessed risk of bias in the included studies using a developed 10-criteria checklist based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies of the National Institute for Health (NIH).20 We neglected 5 criteria of the NIH-checklist that focus on exposures (Q6-Q8, Q10, Q12), as we defined “cancer diagnosis” and “having minor children” as inclusion criteria in advance. To assess the representativeness of included samples as a condition for external validity, we added one item based on the quality assessment tool for quantitative studies of the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP). All criteria could be rated as yes, no, unclear or not applicable (see Supplemental Table S2). The rating of the ten items resulted in a global rating based on the number of fulfilled criteria.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study selection

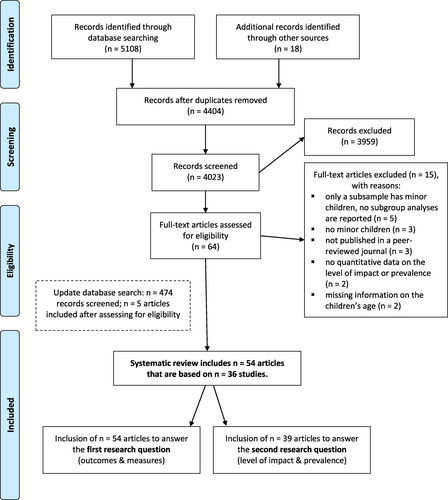

We identified 5108 publications through database search and 18 through handsearching including backward citation. After removing duplicates, 4023 publications were screened based on titles and abstracts and 64 publications remained for the full-text screening of two researchers (LJ, MB). The inter-rater agreement between the two researchers in the full-text screening was 92%. In six publications, where the rating of the two researchers deviated, decisions were discussed and in two publications a third researcher (LI) was consulted. The full-text screening resulted in the inclusion of 54 studies (Figure 1). Common reasons for the exclusion of publications at the stage of full-text screening were that (i) only a subsample had minor children and no data explicitly on parents were reported (n = 5), (ii) the cancer patients had no minor children (n = 3), (iii) the article was not published in a peer-reviewed journal (n = 3), (iv) no quantitative data on the level or the prevalence of mental burden was reported (n = 2) or (v) there was no information on the children's age (n = 2). For an overview of outcomes and applied measures (first research question), we included 54 publications. Of those, we included 39 publications for the synthesis of findings on the levels and prevalence of mental burden (second research question). Studies were excluded at the stage of synthesis for the second research question, if included data had already been reported in another publication with a more comprehensive sample derived from the same study.13, 21-32 Publications based on the same study were only included, if they reported any additional results with relevance to the research questions of this systematic review.

Flow chart of the selection process

3.2 Study characteristics

A total of 54 publications, based on 36 studies, were included (supplemental table S3). Since some publications did not report results on the level or prevalence of mental burden and some results were reported in more than one publication, the synthesis of results on the second research question was based on 39 publications. Supplemental table S4 presents substantial characteristics and findings of the 39 publications reporting relevant information according to the second research question.

3.2.1 Study samples

Among all articles, the systematic search revealed 9 studies with at least 2 publications on the same study sample (see supplemental table S3). In total, articles differed regarding several characteristics. Sample size. The reported sample size of cancer patients with minor children ranged from n = 12 to n = 1809. Focus on family members. While 33 articles focused directly on the parent's mental health situation, seven primarily focused on the children's situation while parental burden was a secondary outcome (e.g., for analyzing associations between parental burden and children's reaction). 13 articles focused on families altogether, and one publication focused on the cancer patient's partner. Geographical region. Data of most articles were collected in Europe (n = 29; n = 18 in Germany, n = 3 in Netherlands, n = 3 in Italy, n = 1 in Finland, n = 1 in Greece, n = 1 in Portugal, n = 1 in UK, n = 1 multinational) and North-America (n = 20; n = 18 in the USA, n = 2 in Canada), followed by Asia (n = 4; n = 2 in Bangladesh, n = 1 Israel, n = 1 in Japan) and Australia (n = 1). Children's age. We only included studies with parents of minor children aged 21 or less. Nevertheless, children's age varied. Children were mostly aged < 18 (n = 21) or ≤ 18 (n = 13), in six articles they were aged ≤ 21 (one article with children between 8 and 19 years), in six articles they were aged ≤ 16 (one article with children between 3 and 14 years) and in six articles they were aged ≤ 12 (mostly called “school aged children”), whereas one article included mothers with newborns < 1 year. Gender. Most articles included both female and male cancer patients. Nevertheless, in the context of 21 publications, only female cancer patients were included. Study design. Most included studies were observational studies using cross-sectional designs. Seven studies focused on interventions in different settings or with different target groups: rehabilitation and after cancer treatment,33, 34 interventions for parents only35-37 and a group intervention for both, affected parents and their children.38 One study obtained data from a prospective cohort study conducted in the context of a cancer rehabilitation program.39 Seven studies had longitudinal designs.29, 36, 37, 40-43

3.2.2 Methodological quality

The results of the methodological quality assessment indicate heterogeneity regarding study quality. Most articles defined clear research questions and were based on secure exposure measures (cancer diagnosis). Only one publication reported a sample size calculation.44 The amount of fulfilled quality criteria varied between 22% and 89%. Comprehensive information on the studies' quality assessment is provided as supplemental material (Supplemental Table S2).

3.3 Synthesis of results

3.3.1 Research question 1: Reported outcomes and measures

Most articles reported the assessment of depression (n = 38), anxiety (n = 28), quality of life (n = 23) and parenting issues (n = 16) . Some publications measured outcomes such as patient's adjustment, perceived stress, overall/cancer-related/symptom distress, mood state or symptoms of a stress-response syndrome after cancer as a major life event. Table 1 summarizes mainly reported outcomes, measures and their frequency of use in included studies. Furthermore, few articles reported measures on other outcomes, for example, using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI, n = 3), the Distress Thermometer (n = 2), the Impact of Event Scale (IES, n = 2), the Profile of Mood States (POMS, n = 2), the National Institute of Health's Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS, n = 2) or the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAM, n = 2). The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised and the German questionnaire on fear of disease progression (Progredienzangstfragebogen, PAF-K) were applied in one article each.

| Outcome | Measure | Frequency of use |

|---|---|---|

| Depression (n = 38) | HADS | 21 |

| BDI | 5 | |

| CES-D | 5 | |

| PHQ-9 | 2 | |

| Zung depression scale | 1 | |

| DASS-SF | 1 | |

| Anxiety (n = 28) | HADS | 21 |

| STAI | 3 | |

| BAI | 1 | |

| GAD-7 | 1 | |

| Parenting issues (n = 16) | PCQ | 12 |

| PaSS | 3 | |

| Parenting stress index | 1 | |

| Quality of life (n = 23) | FACT-G | 7 |

| SF-8 | 6 | |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | 5 | |

| SF-36 | 3 | |

| SF-12 | 1 | |

| EUROHIS-QoL scale | 1 |

- Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Questionnaire; DASS-SF, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale –Short Form; EORTC-QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; EUROHIS-QoL, Scale; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy -General; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PaSS, Parental Stress Scale; PCQ, Parenting Concerns Questionnaire; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form of SF-36; SF-8, 8-item short form of SF-36; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

3.3.2 Research question 2a: Reported outcome levels

Of 54 included articles, 34 articles only reported findings on the outcome level (means and standard deviations), 13 articles reported findings on both outcome level and prevalence of clinically relevant levels of burden and one study only reported results on (depression) prevalence. Six articles only reported results of bivariate analyses (e.g., beta weights or correlations). Levels of mental burden varied according to applied measurement tools (supplemental table S5). Depression levels. Depression levels measured with HADS (total score range 0–21) ranged from M = 3.8 to M = 17.55 indicating normal (score 0–7) to clinically relevant depression scores (score 11–21).5, 38, 41, 45-51 Depression levels measured with CES-D (total score range 0–60) ranged from M = 9.51 to M = 14.63, indicating clinically relevant depression symptoms (score 10–16).35, 37, 43 Depression levels measured with BDI/BDI-II (total score range 0–63) ranged from M = 10.94 to M = 13.4, indicating mild depression (score 10–19).52, 53 Depression levels measured with PHQ-9 (total score range 0–27) ranged from M = 5.32 to M = 10.7, indicating mild to moderate depression symptoms.54, 55 Anxiety levels. Anxiety levels measured with HADS (total score range 0–21) ranged from M = 6.7 to M = 15.72, indicating normal (score 0–7) to clinically relevant (score 11–21) anxiety scores.5, 38, 41, 45-51 Anxiety levels measured with STAI (total score range 20–80) ranged from M = 34.08 to M = 47.41, indicating no/low anxiety (score 20–37) to high anxiety (score 45–80).35, 37, 56 Anxiety levels measured with BAI (M = 8.59) indicated mild anxiety (score 8–15) and anxiety levels measured with GAD-7 indicated a moderate level of anxiety (score 10–14).52, 55 Parenting issues. The total level of parenting concerns measured with PCQ (total score range 1–5) ranged from M = 1.76 to M = 2.33, indicating that parents described themselves as not or little concerned (score 1–2) to somewhat concerned (score 2–3) (based on the categorization of Inhestern et al., 201625). Subscale scores on the practical impact (range M = 1.76 to M = 2.85), the emotional impact (M = 1.84 to M = 2.7) and the patient's concerns regarding the co-parent (range M = 1.55 to M = 2.41) indicate that parents describe themselves as not/little concerned (score 1–2) to somewhat concerned (score 2–3). Although parental stress was measured with PaSS in three studies, only one article reported results. Hence, we could not report a range on the parental stress level. Quality of Life. The total score level of QoL measured with FACT-G (total score range 0–108) ranged from M = 65.5 to M = 70.29. The level of mental health as a component of QoL measured with SF-8 (total score range 0–100) ranged from M = 38.39 to M = 50.6. Level of QoL measured with EORTC-QLQ-C30 (global scale, total score range 0–100) ranged from M = 43.7 to M = 72.2. Emotional functioning as a subscale of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 ranged from M = 35.4 to M = 66 indicating clinically relevant problems in this area.57 Results on levels of QoL measured with SF-36 (total score range for psychosocial summary 0–100) were only reported in one publication, ranging from M = 44.9 in women to M = 49.7 in men. Other Outcomes. Two studies reported findings on results regarding maternal mood applying POMS. The level of total mood disturbance (higher scores indicate a greater degree of mood disturbance) ranged from M = 26.444 to M = 49 (total score range: 0–60).58 Since results on psychological distress measured with BSI (M = 57), the Distress thermometer (M = 4.31, total score range: 0–10) and the IES-Revised (M = 19.83, total score range: 0–88) were only reported in one publication each,38, 44, 49 we could not report a range on findings of parental distress.

3.3.3 Research question 2b: Prevalence rates

Prevalence rates for depression and anxiety are based on summarized findings among articles according to established cut off values (Table 2). Depression. Prevalence of clinically elevated depression levels (HADS score: 8–10, CES-D ≥ 10, PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) in parents with cancer ranged from 9.4% to 59.1%.5, 42, 46-48, 50, 55, 59 Prevalence of probable depression in parents ranged from 7.2% to 82.9%. These estimated rates were based on n = 10 publications,5, 35, 37, 42, 46-48, 50, 53, 55, 59, 60 assessing depression with HADS (score ≥ 11), CES-D (score ≥ 16) or BDI (score ≥ 16). Anxiety. Prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety (HADS score: 8–10) in parents with cancer ranged from 11.4% to 57.1%. Based on n = 6 articles, the prevalence of probable anxiety disorders measured with HADS (score ≥ 11)5, 46-48, 50 or STAI (score ≥ 39)37 ranged from 18.9% to 87.8%. Parenting issues. Regarding parenting issues, findings of one publication indicated that 25% of the patients were concerned regarding their minor children (assessed with self-created open-ended questions).55 Findings of another publication, measuring parenting concerns with PCQ, indicated that 15.6% of the patients had concerns on at least one of the three subscales of PCQ, 13.8% on two of the 3 subscales and 9.6% reported concerns on all 3 subscales.60 There are no publications reporting the prevalence of decreased QoL.

| Outcome | Rating | Measure | Cut off | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Clinically elevated depression (borderline cases) | HADS | score 8–10 | 9.4%–59.1% |

| CES-D | score ≥ 10 | |||

| PHQ-9 | score ≥ 10 | |||

| Probable depression (probable cases) | HADS | score ≥ 11 | 7.2%–82.9% | |

| CES-D | score ≥ 16 | |||

| BDI | score ≥ 16 | |||

| Anxiety | Clinically elevated anxiety (borderline cases) | HADS | score 8–10 | 11.4%–57.1% |

| Probable anxiety disorder (probable cases) | HADS | score ≥ 11 | 18.9%–87.8% | |

| STAI | score ≥ 39 |

- Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

4 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work systematically reviewing quantitative data on the impact of a cancer disease on the mental health of patients with minor or young adult children (≤ 21) . Since the disease's impact on mental health may be defined and operationalized in various ways, this work comprises findings on four relevant outcomes: depression, anxiety, parenting issues and quality of life. Findings demonstrate that the disease and its consequences affect mental health in a varying but overall substantial number of parents with cancer. Between 7% and 83% of affected parents met criteria indicating probable clinical depression and even 19%–88% for probable anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, findings must be considered with caution due to heterogeneity in outcomes, measures, and study characteristics.

Addressing the first research question on outcomes and measures in included publications, we can state that most articles reported to assess depression using HADS, CES-D or BDI/BDI-II and most articles reported to assess anxiety using HADS or STAI. Parenting issues were mostly assessed with PCQ or PaSS and QoL with FACT-G, SF-8 or EORTC-QLQ-C30 . These commonly applied measures seem to represent a weighing of two crucial criteria: First, the manageability, meaning an appropriate number of items, especially in the sensitive context of cancer patients, and second, the measurement's psychometric properties. According to findings of a systematic review of Vodermaier and colleagues (2009) on the assessment of emotional distress in cancer patients, we found that the majority of frequently applied measures are short measures, with a number of items between 5 and 20 (e.g., HADS, CES-D, SF-8, PCQ) and mainly measures with good (e.g., HADS) or even excellent (e.g., CES-D, BDI) psychometric properties.61 By contrast, rarely applied instruments tend to comprise more items (e.g., SF-36) or have poorer psychometric properties according to the work of Vodermaier and Colleagues (2009) (e.g., BAI, Zung Depression Scale).61

Addressing the first part of the second research question on parental levels of mental health impact, findings reveal depression scores indicating normal to clinically relevant depression and anxiety scores indicating normal to clinically relevant anxiety, according to applied measurement tools. While lowest depression and anxiety levels were found in a German study sample of cancer survivors up to six years after initial cancer diagnosis, excluding patients with cancer diagnoses of high mortality rates due to ethical reasons,46 highest rates were found in women of a Bangladesh study with an average of 13 months after diagnosis.5 Parenting issues were mostly assessed with the PCQ. Levels of parenting concerns across all three subscales indicate that parents feel little or somewhat concerned. QoL, measured with FACT-G ranges from M = 65.5 to M = 70.29 and from M = 38.39 to M = 50.6 if measured with SF-8. One study demonstrated that a worse QoL of the mother is associated with a higher need of psychosocial support in both mothers and their children.39

Addressing the second part of the second research question, we can provide prevalence rates for different outcomes and across different applied measures. Between 4% and 59% of parents with cancer met the criteria for clinically elevated depression and even between 7% and 93% met the criteria for probable (pathological) depression. 11% to 57% of parents with cancer met criteria for clinically elevated anxiety and even 19%–88% for probable anxiety disorder. Considering, scoring above a cut-off score may be an indication but not automatically confirm a diagnosis, clinical assessment may be additionally needed. Variations in estimated prevalence rates can be explained by heterogeneity in study designs (e.g., cross-sectional, longitudinal), study populations (e.g., mothers with breast cancer, recently diagnosed cancer patients, cancer survivors) and other study characteristics (e.g., children's age, applied outcome measures, deviating cultural environments). Findings on depression prevalence reveal higher depression rates for single mothers,59 for parents with advanced cancer50 and for parents shortly after cancer diagnosis.47 Lower depression rates were found for cancer patients up to six years after initial cancer diagnosis46 and for partnered women.59 By far the highest depression rates were found in a Bangladesh study sample of married cancer patients with minor children.5 Results on anxiety prevalence indicate higher anxiety rates for mothers47 and parents with an advanced cancer disease.50

A parental cancer disease is associated with consequences for the whole family system, including the children.11, 62 A cancer patient with minor children is not only burdened by dealing with physical symptoms and side effects of the disease and its treatment, but also by concerns of how the disease affects their children's life, how the parental role will or has changed and how to balance one's own needs as a patient and a parent as well.8 The parental status may even influence treatment decisions, leading parents to take additional and/or more aggressive treatments.63, 64 Emotional reactions to a cancer diagnosis can range from understandable sadness and fears (representing a normal response to a stressful life event) to the extent of a psychiatric diagnosis such as depression. We need an underlying fundamental understanding that the care of cancer patients comprises not only medical issues but also psychosocial and parental issues. HCPs need to be open to and sensitive about parental issues during cancer care, asking for family status and enabling affected parents to express their concerns and support needs at any time. Fortunately, several strategies have been evolved to address parental cancer and affected families. First, by providing supporting interventions for affected families in dealing with parental cancer, for example, on inner family communication and coping.65, 66 Second, by empowering HCPs in caring for parents with cancer by enhancing professionals' competencies and awareness.67-69 Third, by sensitizing school personnel to support affected families and especially the children.70, 71 Supporting affected parents with mental burden may not only help the patient him- or herself but the whole family. Therefore, it is necessary to identify how a cancer disease affects the mental well-being of patients including their parental role.

This work has several strengths. While previous studies and systematic reviews mainly focused on the children of cancer patients, their well-being and development, we directly focused on the parent him- or herself. We integrated findings not only on commonly investigated outcomes (e.g., depression and anxiety) but also on parent-specific outcomes (e.g., parenting concerns), representing the wide range of mental burden in our target group of parents with cancer. We consciously did not limit our search to patient characteristics such as cancer type, stage, or treatment. Therefore, we can provide findings that are grounded on an authentic base of study samples, increasing the generalizability. By reviewing quantitative data, we can provide estimated prevalence rates that support and complement qualitative findings on parental burden. Furthermore, we consciously followed the PRISMA guideline, registered the present work within PROSPERO and integrated multiple researchers in full-text-screening, quality assessment and pre-checking of the inclusion checklist for ensuring the methodological quality of this work.

4.1 Limitations

This work has several limitations that need to be considered. We limited database search to studies in English or German, excluding studies published in other languages. We did not limit our search to patient characteristics (e.g., cancer type, stage, treatment, treatment intensity) that may be associated with varying levels of mental health outcomes. Nevertheless, some studies did not include patients with cancer diagnoses of high mortality rates to avoid additional strain on the patients and their families. Included studies also differ regarding sample characteristics and measures. We included studies investigating the mental health of parents parenting children aged 21 or younger. However, the inclusion of offspring aged 18–21 years, may under-represent parental burden since parents of younger children may tend to be higher burdened than parents of older children. Due to this heterogeneity, essential conditions for conducting a meta-analysis were not fulfilled and reported estimates of prevalence rates should be considered with caution. We can only report estimated rates across all different studies and their varying designs. Prevalence rates may under- or overestimate the burden of affected parents as for example several studies exclude potentially high burdened patients in palliative cancer stages with poor physical or mental conditions or with cancer diagnoses characterized by high mortality rates for ethical reasons, as described above.13 Furthermore, most included studies comprised study samples with exclusively women or a large female proportion, mental burden of fathers with minor children is less often investigated. Even if breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer type in women aged between 30 and 64, representing the age range of mothers parenting minor children, we can neither exclude selection bias nor be sure that findings apply for fathers in the same way. Noting that none of the included studies used for example comparative designs it is not possible to attribute parental distress solely to the cancer disease. Possibly, level of distress relates to other unmeasured variables (e.g., social determinants of health). Moreover, because most studies used a cross-sectional study design, we decided on developing a quality assessment checklist based on the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Still, the rating cannot represent the full range of methodological quality criteria and misjudgments are possible due to a lack of reporting in included studies.

4.2 Clinical implications

Our review suggested that there is a great impact of cancer on the mental health of patients parenting minor children. As stated in the World Cancer Declaration of 2013, distress in cancer patients should be routinely measured as the 6th vital sign.72 Screening for parental distress is not only relevant to improve the treatment of the patients themselves, but also because of its association with the child's well-being and psychosocial adjustment. In the context of a patient- and family-oriented care, HCPs should routinely integrate both psychosocial and parental issues into oncological care by asking for the patient's well-being and his or her family situation.

4.3 Conclusion

This review provides a comprehensive overview of existing quantitative data on the impact of cancer on the mental health of patients parenting minor or young adult children. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focusing on quantitative data providing prevalence rates to estimate the number of clinically relevant burdened parents. Our findings support the relevance of screening for mental burden and the relevance of integrating parenting issues routinely into cancer care, since parenthood is associated with additional burden. Nevertheless, more high-quality studies including cancer patients with different cancer types, in different disease stages, of different countries (including lower-income countries) and uniformly applied measurement tools are necessary to validate previous findings. This systematic review may support the sensitivity for the relevance of the mental burden of cancer patients with minor children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The study, in which the present paper is embedded, is funded by the innovations fund of the Federal Joint Committee in Germany (01VSF17052).

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lene Johannsen (LJ) drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and supplemented by the co-authors (Corinna Bergelt (CB), Laura Inhestern (LI), Maja Brandt (MB), Wiebke Frerichs (WF)). CB, LI, WF and LJ made substantial contributions to the conception of this work. LJ and MB were involved in the data searching, data extraction and quality assessment. LI was consulted in case of disagreement between LJ and MB. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The present study does not involve human participants or animal subjects. The comprehensive study, in which the present work is embedded (funded by the innovations fund of the Federal Joint Committee in Germany [01VSF17052]) was approved by the Local Psychological Ethics Committee of the Center for Psychosocial Medicine of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (LPEK-001).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.