Impact of a pharmacist in extended role on an acute mental health ward

Abstract

Specialist mental health pharmacist roles are recognised in providing medicines optimisation for people with mental health disorders. Here, the authors describe an initiative that examined whether a pharmacist could fulfil the role of an ‘extended role practitioner’ on an acute psychiatric ward, so releasing consultant psychiatrist clinical time. The study considers how extended roles such as advanced clinical practitioner can be utilised and service provision redesigned around new patient-facing roles.

The role of specialist mental health pharmacists is well recognised in providing care for medicines optimisation for people with mental health disorders.1–7 Lord Carter's report on mental health services8 recommended that National Health Service (NHS) trusts should develop plans to ensure pharmacy staff spend more time in patient-facing activities in multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's good practice guidance9 recommends pharmacists take a patient-centred approach to medicines optimisation.

In line with the ‘NHS People Plan’,10 which emphasises the need to maximise staff potential, the trust wanted to explore the impact of health care professionals taking on new roles and responsibilities within the MDT.

An experienced specialist mental health pharmacist acted as an ‘extended role practitioner’ (ERP) on one 16-bedded mixed sex acute general adult psychiatric ward to assess the viability of the pharmacist working outwith their usual role to deliver timely access to appropriate interventions and care. The term ‘ERP’ was chosen, being generic, therefore potentially allowing other professionals to undertake similar roles in the future. The ERP role was 0.8 of a whole time equivalent; during the remaining time they continued to deliver a routine daily clinical pharmacy service to that ward.

The objectives of the pharmacist ERP were:

To demonstrate the pharmacists’ ability to provide senior clinical leadership to the MDT on an acute psychiatric ward in line with medical competencies.

To release consultant time from face-to-face patient reviews to use for supervision of senior staff, and other trust strategic objectives.

Methods

The remit of the pharmacist ERP

- Assessment and management of multiple and complicated pathologies.

- Psychiatric history taking, mental state examination, risk assessment and management, mental health diagnosis and case formulation, chairing care planning meetings.

- Managing referrals and the interfaces between teams and other psychiatric and medical teams and service providers.

- Legal responsibilities of an approved or responsible clinician

- Providing evidence to tribunal or manager's hearings

- Other medicolegal work (eg court reports)

- Prescribing medication.

Prescribing was excluded as the aim of this new role was to establish whether another professional would have suitable leadership skills to perform this senior role. The value of non-medical prescribers in mental health services has already been established.11

The pharmacist ERP had 11 years post-registration experience – approximately three years in an acute hospital and eight years in psychiatry across a broad range of services, including acute working-age adult inpatient care, older adults, mental health rehabilitation, psychiatric liaison, learning disabilities, and four years of managerial responsibilities. The pharmacist had completed postgraduate pharmacy qualifications in this speciality (certificate and diploma). There was no crossover between this new ERP role and their existing ward pharmacist role.

The consultant psychiatrist provided weekly supervision to the pharmacist ERP. Workplace-based performance assessments were completed in keeping with those undertaken for psychiatric trainees.12

- Number and types of interventions made by the pharmacist ERP.

- Number of MDT and patient review meetings the pharmacist ERP chaired.

- Proportion of consultant psychiatrists’ weekly workload that was ward-based clinical work over one month, at baseline and compared with one month at the end of the project.

- Pharmacist ERP leadership skills, assessed in line with ST4-6 competencies using the supervision framework and the General Medical Council (GMC) revalidation questionnaire.

- Patient, informal carer, and relatives’ perception of the pharmacist ERP, assessed by a questionnaire adapted from a GMC revalidation tool.

A pharmacist medicine intervention is ‘any verbal or written communication between a pharmacist and a prescriber, undertaken with the intention of influencing prescribing’.13 Based on this we took a non-medicines intervention to be ‘any verbal or written communication between the ERP and MDT, undertaken with the intention of influencing the non-medicine care plan’.

As control measures data were collected for average length of stay (LOS), emergency readmission rate, and number of patients admitted to the mental health unit.

Approval for this pilot role was obtained through the trust's clinical governance structures. Patients were informed of the project and could ask to see the consultant psychiatrist if they preferred.

Results

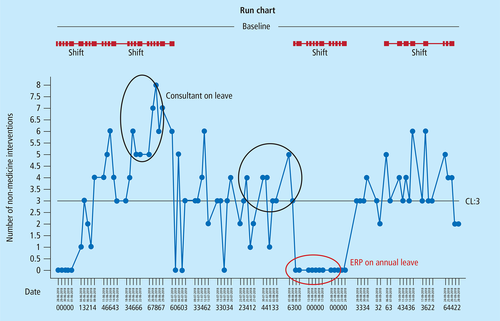

Number of non-medicine interventions

The number of non-medicine interventions shifted significantly over the four-month data collection period. The first shift from zero occurred when the ERP pharmacist integrated into the MDT, peaking when the consultant psychiatrist was on leave. The last shift occurred when the ERP pharmacist worked increasingly independently as they became more confident, leading more MDT handovers and reviews.

Type of non-medicine intervention

To allow subanalysis of the type of non-medicine intervention additional data were collected for one month; interventions were categorised by type. Of the 153 non-medicine interventions made during this period the largest subcategory related to ‘referrals to other professionals, organisations or teams’ (31%, n=47/153), followed by ‘nursing observation level’ (20%, n=31/153) then ‘leave status’ (18%, n=28/153).

A number of non-medicine interventions (12%, n=18/153) were identifying new or pre-existing physical health problems, referring them to other secondary care teams or to the ward doctors for assessment.

Medicines interventions

Over the whole four-month period the number of medicine related interventions was broadly consistent varying between 0–7 per day, although there was a gradual downward trend, reflecting perhaps the impact of having a full-time clinical pharmacist within the team.

Number of ERP pharmacist-led MDT handovers and review meetings

The ERP pharmacist usually led 2 or 3 (range 0–4) MDT patient review meetings throughout each week, updating risk and care plans, in place of the consultant psychiatrist.

Consultant psychiatrist activity

There was a significant reduction in the amount of face-to-face time the consultant psychiatrist spent reviewing patients during the second one-month period compared with the baseline month. This corresponded with a consistent level of MHA-related work and a proportional increase in non-clinical work such as trust strategic and quality improvement activities.

Measures of patient flow

There was no change in average LOS during the project period; it was comparable with the other three general adult acute psychiatric wards in the building. Throughput (number of admissions and transfers per bed) was similar for the project ward as for the other three general adult acute psychiatric wards. There was no change in emergency readmission rate within 30 days of discharge.

Discharge medicine supplies

There were 40 discharges. No patients left the ward without discharge medicines, which were available on average four days prior to discharge.

Patient and carer experience

Thirty questionnaires were distributed to service users, of which 21 were completed (70%) – 16 by patients, 4 by parents and 1 from a spouse or partner. This was felt to be a representative sample. All respondents were confident in the ability of the pharmacist ERP to provide care and 85% were completely happy to see the practitioner again; 15% (n=3) did not answer. There were no negative responses.

Staff perception

Twenty GMC revalidation questionnaires were completed by MDT colleagues. Respondents viewed the ERP favourably and noted no areas of concern. Across the 18 questions 64% (n=231) of responses were rated as ‘very good’, 28% (n=99) as ‘good’ and 8% (n=30) rated as ‘don't know’. The majority (16/18) considered the ERP fit to practice, the remaining 4 respondents were unsure.

Overall, staff perceived the pharmacist ERP as demonstrating behaviours and skills similar to those of a higher trainee doctor and practising safely. Staff specifically highlighted the ERP's teaching input into the MDT as noteworthy.

Discussion points

These data demonstrate that an experienced specialist mental health pharmacist was capable of undertaking the leadership aspects of the role of a higher psychiatric trainee within the MDT. Using this professional in this new way conferred benefits to the MDT at a time when there were challenges in filling medical staffing posts; it enabled the consultant psychiatrist to release time for other key activities.

Importantly, there was no deterioration in any related performance measures for the ward, such as emergency readmissions or patient flow through the ward.

Generally, patients, relatives and informal carers and staff responded positively to the pharmacist ERP role. They considered the ERP to perform in a manner similar that of a competent doctor and met their expectations for care.

There were some unintended additional benefits from the pharmacist ERP role and presence in the ward. For example, all medicine supplies for discharge and leave were on the ward before the days they were required, minimising the chance of a patient leaving the ward without medicines.

For this pilot project the pharmacist was not an independent prescriber, which focussed the attention on the impact of their leadership skills rather than prescribing activity. Prescribing was done by medical staff based on recommendations by the pharmacist (de facto prescribing). Medical staff could challenge, discuss changes to medicines and escalate any concerns to the consultant psychiatrist. It is anticipated that had the pharmacist also been a prescriber then the de facto prescribing would have moved to prescription writing, which may be a further benefit.

The pharmacist ERP was not qualified as an advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) and had not undertaken enhanced clinical diagnostic skills training. At the time of the project these qualifications were not widely available for pharmacists in mental health settings.14 Following this successful pilot project the service chose to continue the role through an ACP nurse who was a prescriber. This has led to ACPs being engaged in other areas of clinical practice and reconsideration of the use of non-medical prescribers (NMPs) in services.

Conclusions

This pilot project demonstrated that a pharmacist could successfully undertake an extended role in the MDT fulfilling many roles of a higher trainee psychiatrist in addition to their traditional clinical pharmacist role. This new ERP role was widely embraced by staff, patients and informal carers. It is envisaged as that as a prescriber there could be even greater benefit to this development. Extended roles such as ACPs should be explored and service provision may need to be redesigned around new patient facing roles.

Key messages

- Specialist mental health pharmacist roles are recognised in providing medicines optimisation for people with mental health disorders.

- In secondary care mental health services pharmacists commonly work as part of the MDT. Some have extended roles in medicines optimisation as qualified prescribers.

- This study demonstrated that a specialist mental health pharmacist has suitable skills to provide similar leadership to the MDT as a senior trainee doctor.

- The pharmacist successfully fulfilled the remit of the new role, which was beyond the traditional one in medicines optimisation or supply.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and service users of Danube ward, St Charles Hospital; the pharmacy team and the medical directors of Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust for allowing and enabling this project to occur.

Declaration of interests

No conflicts of interest were declared.