Empowerment-based education for established type 2 diabetes in rural England

Abstract

People with newly-diagnosed type 2 diabetes are offered structured education, but there are few programmes for those with established diabetes. The empowerment-based education approach from the United States has been advocated as one approach that supports self-management, but is not used in England. The aim of this study was to assess the acceptability of empowerment-based diabetes education for patients with established type 2 diabetes.

One 3.5-hour workshop was offered to participants joining a trial of peer support in rural Cambridgeshire, UK. Four main aspects of self-care (carbohydrates and portion size; truths and myths about diabetes; know your numbers and medications; keeping active and foot care) were addressed, followed by a question and answer session. Change in diabetes knowledge and participant perspectives were evaluated using questionnaires. Qualitative evaluation was by ethnographic observation of sessions.

Patient expectations were met in 93.5% of participants. Aspects thought to be particularly useful related to diet and carbohydrates and also medications. Ethnography revealed five main themes: diet, group process, health service experience, within session peer support, and educator clinical grounding. Sixty percent of those participating increased their ability to answer diabetes knowledge-based questions.

Adopting the ‘empowerment approach’ is a valid method of diabetes education for those with established type 2 diabetes in England. Delivery by experienced educators is important to address queries that arise during the sessions. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons.

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing,1 placing a growing burden on individuals, their families and health care systems.2 The cornerstone of management includes appropriate lifestyle choices supported by regular medication and blood glucose self-monitoring, where necessary. As daily care of diabetes is carried out almost entirely by the patients, it is especially important that they develop adequate self-management skills and healthy behaviours in relation to their diabetes.3

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a fundamental component of diabetes care that helps patients acquire the required knowledge, information, self-care practices, coping skills, and attitudes.4 The overall objectives of DSME are to support informed decision making, self-care behaviours, problem-solving and active collaboration with the health care team, and to improve clinical outcomes and quality of life.5 DSME interventions have a positive impact on diabetes-related health and psychosocial outcomes, specifically increasing knowledge and improving blood glucose monitoring, dietary and exercise habits, foot care, medication taking, coping, and improving glycaemic control, systolic blood pressure and weight.6-8

In the UK, there are two national structured, evidence-based education programmes for those with newly-diagnosed type 2 diabetes: DESMOND9 and X-PERT.10 However, there is less evidence for educational programmes for those with established type 2 diabetes in the UK.11 In the United States, the ‘empowerment’ approach to diabetes education, where content follows the questions from participants rather than in a structured format, has been shown to be beneficial in a randomised controlled trial.12

This study tested whether the ‘empowerment’ approach to patient education is acceptable and effective in increasing diabetes knowledge among patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes in the East of England.

Method

Participants and setting

This was a prospective, observational study of an empowerment approach to type 2 diabetes education, prior to randomisation in a randomised controlled trial comparing the impact of group and/or 1:1 peer support on metabolic control (RAPSID: RAndomised controlled trial of Peer Support In type 2 Diabetes – ISRCTN 66963621).13 All participants were invited to participate in diabetes education, using the same format, independent of, and prior to, commencing in their allocated peer-support intervention. All participants also received a type 2 diabetes management booklet. For the control group, the education session and the booklet were the only interventions received.

Adults with type 2 diabetes were invited into RAPSID from across Cambridgeshire, and adjacent areas in Essex and Hertfordshire, UK. Participants were recruited mainly through general practice, with a minority responding to posters in the community, as previously described.13 Those with terminal illness, psychosis or dementia were excluded. Following consent, baseline measurements included HbA1c, lipids, anthropometric measurements, blood pressure and measures of depression (PHQ814), quality of life (EQ5D15), diabetes self-efficacy,16 the Revised Diabetes Knowledge Scale (RDKS17), and diabetes distress.18 All consenting participants were offered a single diabetes education session prior to randomisation into the trial.

Education intervention

The education intervention was delivered in groups of up to 15 to build on group learning processes and held at local community centres, general practice or hospital venues. The format was based upon the ‘empowerment approach’19 and was delivered using a variety of interactive tools (group discussion, quizzes, experiential learning and identifying carbohydrates). The role of the facilitator (a diabetes specialist dietitian or nurse) was to engage the participants in group discussion, increasing awareness about diabetes-related facts while maximising peer learning and activities that would enhance their understanding of self-care.

- Identifying carbohydrates and understanding portions.

- Truths and myths about diabetes.

- Knowing your numbers and medications.

- Keeping active and looking after your feet.

Evaluation

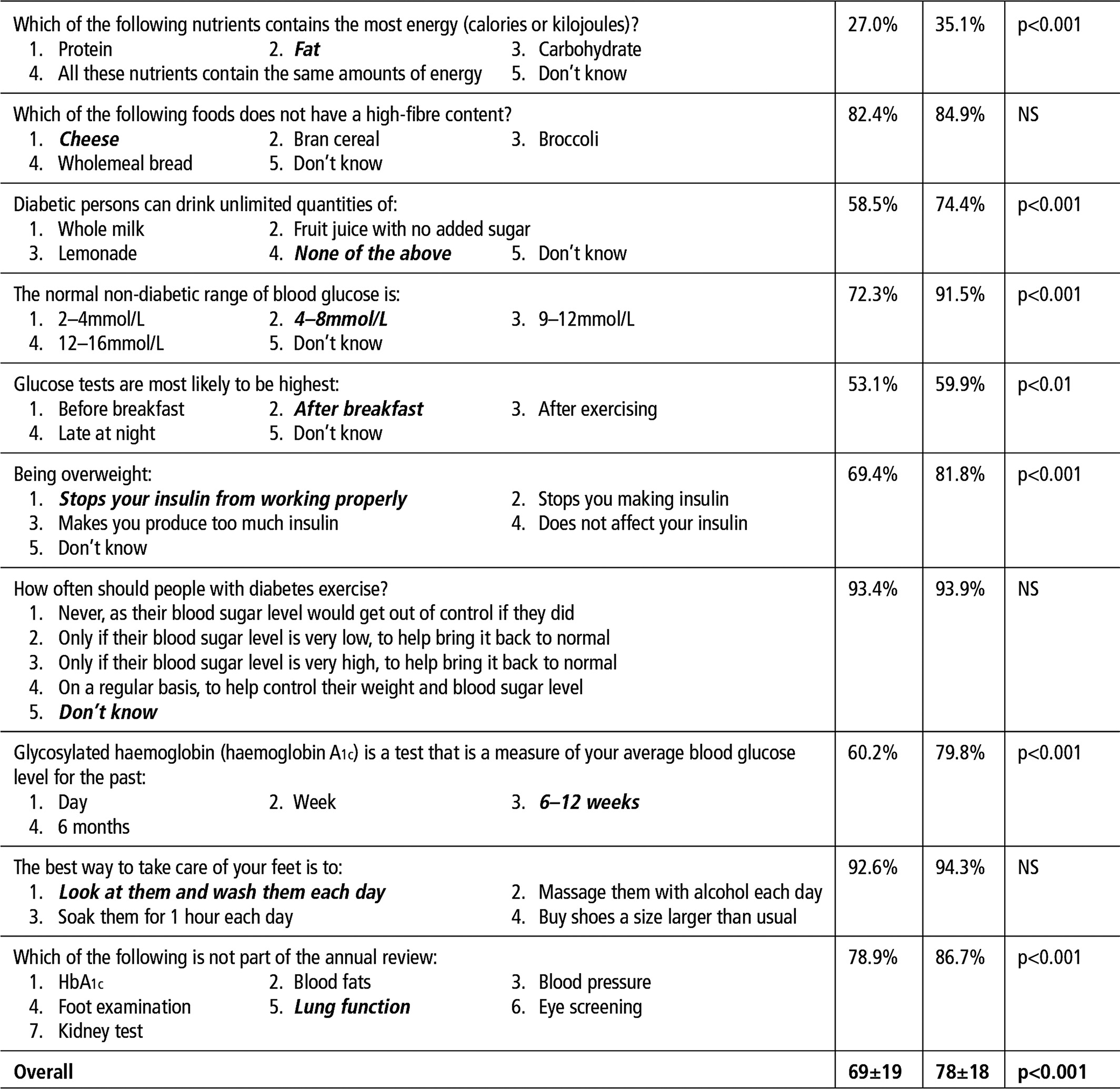

Knowledge about diabetes was assessed by participants being asked to complete the RDKS at the beginning and end of the education sessions.17 The original instrument consists of 23 knowledge test items developed and validated by the Michigan Diabetes Research Training Center.17 The first 14 items are a general test, with an additional nine-item sub-scale which is only appropriate for people who use insulin. To tailor the questions to the aims of the education programme, 10 items were selected, covering food (three items), blood glucose, glucose testing, weight management, physical activity, HbA1c, foot care and the annual review.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 19. Characteristics were compared using analysis of variance (continuous variables) or chi-squared (discrete variables) test. The effect of the group session on the proportion of correct answers was tested by paired-sample t-tests. The characteristics of those who increased their scores by ≥10% were investigated using stepwise logistic regression. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All tests were 2-tailed.

At the end of the workshop, participants were also asked to complete an anonymous evaluation form which asked what they found most and least useful, and whether their expectations were met.

Ethnographic observations

Thirty-six of the 128 education sessions were observed by a social scientist (CB) using ethnographic methods.20 The researcher's presence and purpose were made known to the participants both at the education sessions and in the study consent form. Notes were taken by hand, transcribed and entered into NVivo 10 for analysis, using a grounded theory approach.21 A subset of the transcriptions was read by another social scientist to check the interpretive processes through which the emergent themes were derived. Ethics approval was received from the Cambridgeshire REC2 Committee.

Results

Across the 63 participating practices: 21 961 were invited to join the RAPSID trial; 3932 responded to the invitation; 2028 of these responses were positive; 1366 were recruited and, of these, 797 (58.3%) attended the diabetes education sessions. Randomisation occurred after the education session and 1299 were randomised to one of the four arms.13 Despite contacting participants three times, some were unable to attend one of the 128 educations sessions on offer. Of those attending, 578 completed the RDKS before and after the session, and Table 1 provides information on these. A further 38 completed the RDKS only before and 17 only after the session. Those completing the RDKS before and after the session were similar to others besides having a lower BMI (data not shown). Observation data indicated that participants who did not complete both before-and-after RDKS tended to either arrive late or to have a need to leave early (such as another social engagement), and that some chose not to complete the questionnaire, perhaps due to literacy issues.

| Characteristics | n=578 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65±10 |

| % male | 56.7% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.7±5.6 |

| Non-British origin | 7.6% |

Educational qualifications:

|

19.0% 33.4% 26.0% 21.5% |

| Attended diabetes education session before | 54.8% |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 9±11 |

| Insulin treatment | 18.4% |

| HbA1c mmol/mol (%) | 57±14 (7.4%) |

| PHQ8 depression score (0–24)* | 4.4±4.9 |

| EQ5D quality of life score (0–1)** | 0.77±0.26 |

| Diabetes self-efficacy (8–80)** | 58±16 |

| Diabetes knowledge score (0–15)** | 11±3 |

| Diabetes distress (4–24)* | 6±4 |

- Data shown are mean ± SD or %.

- * Reference range: lower means better.

- ** Reference range: higher means better.

Table 2 shows that more correct answers were given after the session, particularly in relation to sugary drinks, the normal blood glucose range, the impact of excess weight on the action of insulin, and HbA1c. Overall, 60% increased their correct answers by at least one question. Those taking insulin increased the proportion of correct knowledge answers by five (95% confidence interval: 3–8) while others increased theirs by 10 (95% confidence interval: 9–12). In a logistic regression, those increasing their correct answers by ≥10% had a lower proportion of correct answers at baseline but no other variables showed significant associations.

Workshop evaluation

The post-session evaluation form was returned by 456 participants. In all, 193 (42%) reported that learning about diet and foods was most useful, 71 (16%) referred to learning about diabetes and its management, 26 (6%) referred to the format of the sessions and discussing the condition with others, 80 (18%) said it was ‘all useful’ and 78 (17%) left this blank. Only 70 (15%) identified any aspect as ‘least useful’. Adverse comments on content related to: medication (n=15), diet and foods (n=10), medical information about diabetes (n=8), alcohol (n=5), and exercise (n=3). Some found the quizzes and flipcharts unhelpful (n=6), were irritated by other participants (n=6), or felt the session was too long or complicated (n=6). A total of 93.5% said the session met their expectations.

Ethnographic observations

Dissecting diet

The group interactions observed by CB suggested that participants found the material on diet and food to be of most use, in line with the survey results. The allotted time for discussion of dietary practices often over-ran and groups frequently spent much of their time asking educators to comment on advice they had received in the past. Discussion was not limited to advice received from health professionals, but also extended to suggestions that patients had received from others with diabetes, as shown in Table 3. In the latter case, it seemed that the educator was steering the group away from unhelpful and scientifically problematic advice rather than allowing the dietary ‘myths’ to become a focus of conflict between the ‘expert’ health professional and the ‘naïve’ patient. The educator empowered participants by offering them an alternative understanding of how beans and root vegetables interact with blood glucose levels.

| Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Dissecting diet – health professional advice | PB3: ‘But I was told not to eat the ripe ones [bananas] by the diabetes specialist nurse at the surgery. She also said don't have bananas and grapes on the same day – I can have one or the other.’ Ed1: ‘That's not true. You can have them on the same day, you just have to space them out.’ |

| Dissecting diet – advice from others |

PF6: ‘Runner beans and French beans, they're meant to be a no-no, aren't they?’ Ed4: ‘No, I wouldn't say that. We've got no reason to think runner or French beans are bad for your blood glucose. Quite the opposite – they're good for you. I've never heard of that before.’ PF2: ‘It's the things that grow underground that you have to worry about – it's all sugar, isn't it? I mean, that's the gardener's rule.’ Ed4: ‘I see your point, [PF2], but with many foods it's not true, like carrots. They have some carbs in them, but we don't break it down, so we don't count it. When we break down foods in labs, we find every last chemical. But our bodies aren't labs – they don't get everything out of food, so some things remain. With carrots, and as we said about broccoli earlier, the sugar doesn't get accessed.’ |

| Group consultations |

PH6: ‘I have a pork pie on the golf course – I usually feel a little faint around hole 9.’ Ed4: ‘And what food group is that?’ PH6: ‘All 3, I think.’ Ed4: ‘Yes, but not much carbohydrate, so it won't help you – it's mostly fat and protein.’ PH6: ‘Ah yes, okay.’ Ed4: ‘You need to talk to your GP – it might be that when you exercise, you need to reduce the tablets.’ |

| Experiencing health services |

PBA3: ‘My diabetes nurse is a little Rottweiler, if the levels go up, she's on it! A right task master! She's great – I feel she keeps me on track.’ PBA7: ‘You must go to the same surgery as me – she's a cracker, isn't she?’ PBA9: ‘Well I don't know what you're talking about – my nurse never tells me any of these numbers – I've not heard of this HABC thing.’ Ed2: ‘Unfortunately not every health professional takes the time to explain these different tests and numbers. But they should!’ PBA2: ‘You should ask – it's your body. I think I'm at the same practice as you and I asked and they gave me one of these record cards – I have all the numbers for the last few years.’ |

| Peer support |

PY3: ‘And I often forget to take my tablets – they're usually right in front of me, but I still forget.’ PY5: ‘You should get a pill box.’ PY4: ‘Yeah, mine's fantastic. I put it next to the kettle – keeps it in my mind!’ PY3: ‘A wonderful idea!’ |

- Participants are labelled by their interview number. Ed = educator.

Group consultations

The empowerment approach that informed the educators’ responses to dietary queries helped establish a dynamic resembling that of a clinical consultation, but within the group setting. Patients often raised questions about their condition, how it is monitored and what actions they should take in situations they find themselves in, such as hypos. A typical exchange is shown in Table 3, where the educator responds to PH6's practice of eating pork pies to alleviate ‘feeling faint’ on the golf course by reasoning out the low carbohydrate content of the food. However, the consultation dynamic often expanded beyond exchanges between individual patients and professionals into something approaching a ‘group consultation’.

Experiencing health services

Participants swapped experiences of the health service, usually during the section on what they should expect from annual review appointments. Because most sessions brought together patients from either the same GP practice or from neighbouring areas, much of the discussion related to the minutiae of local health care provision and identified disparities between the care received within the group. The example in Table 3 shows PBA9 receiving encouragement from a patient registered with the same GP practice, as well as from the educator. In such moments, the education session moved beyond didactic delivery of information, and allowed participants to compare their experiences of the health service with those of others.

Peer support

Participants often began to discuss the idea of helping one another as a key aspect of the RAPSID trial. In some instances, this led participants to exchange ideas and experiences relating to self-management, as shown in Table 3. Through such exchanges, participants began to share techniques for self-management and thereby to support their peers.

Clinical grounding

The clinical experience of the educators allowed them to establish a trusting environment in which they were able to facilitate participants to explore their diets, medications, conditions and experiences of health care and to begin to support one another. The fact that the educators who delivered these sessions were experienced dietitians and specialist nurses used to delivering group education and working within a multidisciplinary diabetes hospital clinic, allowed them to speak with confidence about this host of topics. The importance of this clinical grounding was also evident in the interaction in Table 4, where Ed3 invokes a multidisciplinary ‘we… in the clinic’. By offering a balanced and experientially-grounded account of why some patients are asked to use test strips and others are not, Ed3 was able to add to the group's understanding of the ‘NHS position’ without disregarding or reinforcing PC3's objections.

| Participants | Quotations |

|---|---|

| PC2 | ‘What about testing? We haven't spoken about this. I don't test, but I did to start with. My GP won't let me now – he tells me that those on pills don't need to test, as they can't adjust their medication.’ |

| Ed3 | ‘That's often said – it's the NHS position on testing at the moment.’ |

| PC3 | ‘I don't agree with it all – we should be given test strips. I was given them when I was first diagnosed and I used them to work out how different foods affected me. It was so useful. It still helps now.’ |

| PC2 | ‘Yes, I always felt that would be useful, but one doesn't like to question the doctor!’ |

| Ed3 | ‘Absolutely, I understand – and, yes, [speaking to PC3], you're right. We often do this kind of thing with the patients in the clinic. It helps some get control. But for many it is true that there is no need to test.’ |

| PC3 | ‘Okay, that makes sense. I guess not everyone gets something from the strips, but I know I do. Maybe I'm like those you see in your clinic.’ |

- Participants are labelled by their interview number. Ed = educator.

Discussion

Our study has shown that the ‘empowerment approach’ for ongoing education for those with type 2 diabetes is acceptable, increases knowledge and provides the opportunity to tailor education to patients in the group setting. The impact of such education programmes on metabolic control are notoriously difficult to evaluate, with a recent meta-analysis suggesting a minimum of 10 hours per annum is needed to reduce HbA1c among patients with type 2 diabetes.22

Indeed, even with patients with newly-diagnosed type 2 diabetes, education was associated with improved HbA1c in X-PERT,10 but not DESMOND. Bearing this in mind, as the original evidence for adopting the ‘empowerment approach’ came from the US following a randomised controlled trial, it was felt that its adaptation to a UK setting needed evaluation in terms of its acceptability and impact on knowledge, rather than in a trial with clinical outcomes, i.e. equipoise had already been reached.

This programme had a purpose different from the original empowerment programme,19 which is a series of six sessions, and the X-PERT and DESMOND programmes for those with newly-diagnosed diabetes. The sessions were not designed to address skills acquisition (e.g. glucose monitoring or insulin self-treatment). Structured diabetes education was available across the study area for those who were newly diagnosed so, in principle, all that should have been needed was a ‘catch up’. However, the questionnaire revealed that only 54.8% had previously received structured education. Many would otherwise have had education from the practice nurse or perhaps a visiting dietitian. Even so, the low level of knowledge was surprising and suggests that more diabetes education is needed. The demand for knowledge about food/diet was a consistent theme, highlighting a potential gap in existing services.

The ethnographic study also suggested that delivering this ongoing diabetes education requires a high level of experience and skill. This may be better delivered by those with past participation in a multidisciplinary hospital clinic or relevant further training in diabetes care, so that a broader range of experiences can inform the answers given.

One gap in patient diabetes education in the UK is its provision to those who have already undertaken structured education.23 X-PERT has developed a module and DESMOND advises that theirs can be used in this way; however, neither has been validated and the cost would probably be more than this 3.5-hour session. It is suggested that the approach used here could be offered on a regular basis, perhaps annually, organised locally to answer questions, address new developments and fill any important gaps in knowledge. Those taking insulin should receive a separate programme. One key feature would be to ensure a quality assurance and training framework to mandate consistency and quality, as included in the NICE recommendations11 and consistent with current work on health professional competency frameworks.24-26 This would fit well with the current national X-PERT programme.27

Strengths and limitations

Repeating a questionnaire could reflect question familiarity (i.e. the participants were sensitised to the questions asked before the session) and the topics covered were limited, hence the improvement in response did not necessarily reflect a similar degree of learning. However, the ethnographic observations confirm a learning environment was created and the anonymous post-workshop evaluation showed that the participants felt that they benefitted from the session. Those treated with insulin had less benefit, possibly because they knew more beforehand from their prior education about insulin. Another limitation was the relatively low participation rate, which was largely a product of practical difficulties in arranging sessions in spite of multiple contacts and with organising sessions at local venues.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that a 3.5-hour diabetes education session, following the United States developed ‘empowerment approach’, is associated with an increase in knowledge and is well accepted and appreciated by participants. The study poses the question as to whether a regular session like this should be arranged for all patients with type 2 diabetes and if it were, whether this would lead to significant improvements in patients’ effectiveness in managing their diabetes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peers for Progress and the Clinical Research Network for financial support, the Primary Care Research Network and Medical Research Council Units for assistance with recruitment, and Takeda for educational materials. We also thank Caroline Taylor, Anne Marie Monk and Kim Mercer for administrative support, and James Brimicombe for assistance with the database. We thank Simon Cohn for assistance with the study including support for the qualitative analyses.

Ethics approval was received from the Cambridgeshire REC2 Committee.

Declaration of interests

Key points

- A short diabetes education session following the empowerment approach was associated with an increase in knowledge, was well accepted and appreciated by the participants, and provided the opportunity to tailor education to patients in the group setting

- The approach used here could be offered on a regular basis, perhaps annually, organised locally to answer questions, address new developments and fill any important gaps in knowledge. However, those taking insulin should receive a separate programme

- The ethnographic observations demonstrated a learning environment was created, and the anonymous post-workshop evaluation showed that the participants felt that they benefitted from the session