A Toolkit for Healthcare Transition for Adolescents With Classical Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

ABSTRACT

Classical myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are being identified more frequently in adolescents. There is no guidance on the healthcare transition of young MPN patients from pediatric to adult medicine. Therefore, we convened an international panel of experts in both pediatric and adult MPN care to develop three tools to facilitate high-quality healthcare transition: a physician education tool, a transition readiness assessment tool, and a consensus statement of practice recommendations to ensure a more seamless transition in the care adolescents receive. These tools can help ensure a better healthcare transition for young patients. The next steps include evaluating the readiness assessment tool with adolescent patients.

Abbreviations

-

- AAP

-

- American Academy of Pediatrics

-

- ASH

-

- American Society of Hematology

-

- AYA

-

- Adolescent and young adult

-

- ET

-

- Essential thrombocythemia

-

- HCT

-

- Healthcare transition

-

- IFN

-

- Interferon

-

- MPN

-

- Myeloproliferative neoplasm

-

- PMF

-

- Primary myelofibrosis

-

- PV

-

- Polycythemia vera

1 Introduction

Classical myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)—including essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF)—are chronic clonal marrow disorders complicated by varied clinical symptoms, thrombohemorrhagic events, and the potential for transformation to myelofibrosis and acute myeloid leukemia. While MPNs were historically thought of as diseases of older adults, there is now more data on children, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with MPNs [1-3]. It is thought that with the increased use of automated blood count analyzers, increased awareness of cancer and cancer prevention, and the availability of genetic testing, MPNs are being diagnosed more frequently in childhood [3, 4]. Patients with MPNs under the age of 40 years have been reported in recent cohorts to constitute anywhere from 5% to 27% of MPN populations [2, 5–7].

ET is the most common classical MPN diagnosed in young patients, and there are higher rates of “triple-negative” disease in younger patients (lack of an identified driver mutation in the JAK2, CALR, or MPL genes) [1, 2]. Young patients with MPNs are at risk of the same complications of MPNs as older adults, including thrombosis, bleeding, and disease transformation. JAK2V617F mutation is associated with thrombosis in young patients, while CALR mutation is associated with disease transformation, with lower occurrences of these complications in triple-negative patients (which is similar to older adults) [1, 2, 8–10]. Younger MPN patients have been reported to undergo bone marrow evaluation more frequently than older patients [11], and risk scores used in adults are largely untested in young patients [1].

Healthcare transition (HCT) is defined by the National Institutes of Health Pediatric Research Consortium as “The purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions or intellectual or developmental disabilities from child-centered to adult-oriented healthcare in a way that considers typical developmental processes at this stage of life as well as access, appropriateness, and continuity of healthcare services” [12]. Despite being a crucial part of the care for young patients, prior studies show that many children are not receiving transition preparation, with one national study demonstrating that 84% of adolescents with special healthcare needs did not receive adequate HCT preparation based on national performance measures (including time alone for the teen to speak to their physician and discussion between the physician and teen regarding seeing doctors who treat adult patients) [13]. Barriers to the transition process include issues related to insurance, distance from adult specialists, unstable living conditions, and lack of understanding of parents/caregivers of their role in helping teens gain independence as part of the transition process [13].

Lack of formal healthcare transition is associated with numerous adverse outcomes, including medical complications, increased emergency department use, and poorer medication adherence [12, 13]. Much work has been done in this area for more common illnesses, such as sickle cell disease [14, 15], yet there is no guidance on how to transition an adolescent with an MPN from a pediatric to an adult provider. Given the increasing recognition of MPNs occurring in the pediatric population, some differences in disease features between older and younger patients, and the importance of HCT, we sought to develop a toolkit to help guide the transition of care for young MPN patients.

2 Methods

2.1 Expert Panel

We convened an international panel of MPN physicians from France, Germany, Italy, and the United States to develop the materials necessary to safely transition young MPN patients from pediatric to adult practice. Pediatric and adult hematologists with expertise in caring for adolescent and young adult patients with MPNs participated in the panel. We felt it was important to create a partnership between pediatric and adult medicine to ensure both perspectives were included and encourage ongoing collaboration between pediatric and adult colleagues. Seven virtual panel meetings were held over 14 months.

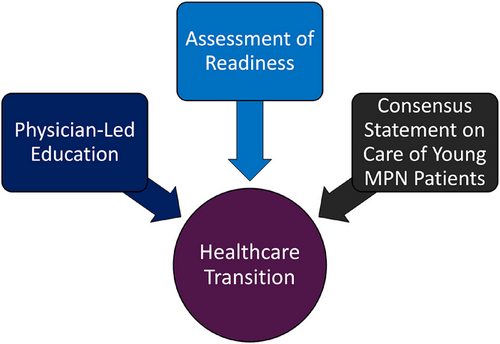

2.2 Toolkit Development

We identified three components for a comprehensive MPN-focused HCT toolkit (Figure 1) including an educational checklist for physicians to help guide their teaching of adolescents with MPNs, a transition readiness assessment tool to help gauge a young patient's readiness for transition, and a short consensus statement regarding clinical practice recommendations for both teens and younger adult patients to allow for consistency in care. The American Society of Hematology's “General Hematology Transition Readiness Assessment” tool [16] was used as a template from which the MPN transition readiness assessment tool was developed. The tool first assesses “transition importance and confidence” and seeks to understand the adolescent's general interest in self-management and confidence in their abilities using a 0–10 scale. The main portion of the tool focused on “my health and healthcare” parallels the education checklist, with three sections: disease knowledge, disease monitoring and treatment, and appointment management. A Likert scale of “no,” “sometimes,” and “yes” assesses the adolescent's level of agreement throughout the tool.

The education checklist was designed with a complimentary structure to the readiness assessment tool to help guide physicians when they educate their young patients on MPNs. Available literature and panelist experience and expertise were used to develop the consensus points, providing levels of evidence of Level C-LD (which includes limited data such as those found in observational or registry studies) and Level C-EO (which includes expert opinion consensus based on clinical experience) as per the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [17]. The final versions of all three documents were agreed upon by all panel members. This toolkit is designed to be used starting in the early teenage years, and can continue through later adolescence/early young adulthood until the healthcare transition is complete.

3 Results

3.1 Education Checklist (Table S1)

To prepare an adolescent for transition to adult care, education on various elements of their disease is paramount. To help physicians provide this education, we developed a checklist of key points for physicians to discuss with their young MPN patients to better prepare them for managing their own healthcare needs. This document was divided into the following sections: disease knowledge, disease management, and appointment management. This checklist is meant to provide a guide for physicians, which can be individualized as needed. We recommend that it be incorporated into multiple visits with an adolescent patient.

Disease knowledge included recognition of what an MPN is, what type of MPN a patient has, and understanding the chronic nature of these disorders. Disease-specific key points included recognizing the risk of thrombosis and lifestyle factors that could add to thrombotic risk, the possibility of symptoms associated with MPNs, and the concepts of disease transformation (such as ET developing into PV), or progression of MPNs to overt myelofibrosis or acute myeloid leukemia over time. It is important to educate patients on the different risks of thrombosis and disease progression with different driver mutations (i.e., patients with JAK2V617F mutations have an increased risk of thrombosis [1, 4]). The panel also thought it was important to introduce the concept of MPNs potentially affecting fertility and pregnancy. Disease management includes highlighting different aspects of an MPN that contribute to treatment decisions, a review of various treatments used in MPNs, and factors to consider when selecting the most appropriate therapy. Patients on medications should be educated about the drug, including potential side effects. The checklist also recommends introducing the concept of clinical trials to teen patients, as there are many clinical trials available to adult MPN patients. Appointment management knowledge includes various aspects of attending a medical appointment, including being able to complete a medical history and carrying a copy of their insurance card.

3.2 Readiness Assessment Tool (Figure S1)

In the first section, disease knowledge is assessed with statements that focus on MPN type, risk factors for thrombosis, clinical symptoms of thrombosis, symptoms of MPNs, and disease progression. The second section on disease monitoring and treatment assesses knowledge of disease monitoring, such as routine labs and bone marrow studies, and knowledge of treatments for MPNs. This section also evaluates specific knowledge regarding a medication an individual patient may be taking. These first two sections are more specific to hematology and MPNs, whereas the appointment management section addresses healthcare office visits and knowledge of appointment processes, insurance and referral understanding, and emergency access. The tool ends with an opportunity for the adolescent to set a goal for that day's visit. This tool is meant to be administered at consecutive visits to allow the adolescent to achieve a response of “yes” for more and more knowledge assessments.

It has been suggested that the use of transition readiness assessment tools could begin as early as 14 years of age [18]. We propose using the educational checklist to guide the formal teaching of adolescent patients beginning at age 14 years, and to begin utilizing the readiness assessment tool at 16 years. There have been varied recommendations for the frequency of administering readiness assessment tools, and we would recommend this tool be administered every 6 months. This would provide ample opportunity to provide age-appropriate education, evaluate changes in knowledge and readiness over time, and have both the patient and the clinician identify ongoing areas of needed education.

3.3 Consensus Statement on the Care of Young MPN Patients (Table S2)

Recognizing the challenge in ensuring continuity of care between pediatric and adult practice, and the theoretical benefit continuity could provide to ease the burden of transition, the panel felt strongly that identifying some points of consensus to help guide management was essential for this transition toolkit. The consensus management points were separated into diagnosis and management sections, with management including monitoring, counseling, and treatment. The panel agreed that with rare exceptions, a bone marrow examination was necessary to properly diagnose an MPN. In addition to evaluating for the presence of known driver mutations, the panel recommended checking variant allele frequency of known mutations and a broader myeloid gene panel when feasible, recognizing that this testing is not accessible everywhere. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was recommended at diagnosis to evaluate spleen size and ensure no splanchnic thrombosis was present, and routine reimaging every 1–3 years should be considered, especially in those with difficult abdominal exams.

The panel agreed that labs should generally be monitored every 3–4 months, and this could be adjusted for patients on cytoreduction therapy or those experiencing changes in clinical symptoms. Routine bone marrow follow-up evaluations were not recommended for patients with stable clinical and lab findings. Our panel also agreed that patients should be counseled on thrombohemorrhagic risks, including the potential thrombotic risks associated with pregnancy or use of hormonal contraception (two areas with very limited guidance in MPNs), and hemorrhagic risks associated with participation in contact sports in the setting of acetylsalicylic acid or anticoagulation use or presence of acquired von Willebrand's disease.

One of the most critical points agreed upon by the panel was that treatment should not be initiated in a young MPN patient based solely on the height of the platelet count. We agreed that cytoreduction medications were indicated for thrombohemorrhagic events and could also be considered for symptoms or bleeding risks that were affecting quality of life, as the goal of treatment should be to help young patients feel and live well. Based on recent data [19-21], the panel agreed that treatment with pegylated interferons (IFN) should be considered for the possibility of improving long-term outcomes, specifically in young patients with JAK2V617F- or CALR-mutated MPNs. Our panel agreed that IFN was the preferred first-line agent for cytoreduction when available.

4 Discussion

MPNs are most common in adults over 60 years old [1, 22], which means that data used to develop diagnostic criteria and management recommendations are largely derived from, and geared toward, older patients [23]. The issue of HCT was not previously recognized as being important for MPN patients given their typical age, yet we now know more young patients are being diagnosed with MPNs [3]. Therefore, it is imperative to ensure we prepare our adolescents with MPNs for the transition from the pediatric to adult medical home. This international collaborative work represents the first opportunity to specifically support HCT for young patients with classical MPNs by developing disease-specific educational and assessment tools and offering some suggested practice elements that can be adopted by both pediatric and adult providers.

Our first item for the transition toolkit was an education checklist for physicians because education is essential for preparing a teenage patient for HCT, especially for someone with a rare disease [14, 24]. Based on recommendations of the AAP, the process of HCT should begin well before a patient leaves their pediatric practice and the checklist allows for inclusion of disease-specific teaching at each visit. Providing a concise checklist of important points for physicians to use to guide their patients’ education will ensure proper education of young patients before they transition. For pediatric hematologists/oncologists who may not have much clinical experience caring for young MPN patients, this could be a valuable tool. It could also be of use to adult hematologists who have limited experience with younger MPN patients.

Caregivers play an important role in the HCT process. Healthcare in childhood is largely caregiver-driven, and HCT means moving to a patient-driven model of care. Often, caregivers do not feel their child is able to, or comfortable with, participate in healthcare conversations and decisions, and may have hesitation in letting their teen lead [12, 25]. Caregivers need to support and encourage young patients to gain the necessary knowledge about their disease and the healthcare system to begin to direct their own care [4]. Whenever possible, clinicians should try to include caregivers in their educational sessions and should partner with caregivers to help educate and embolden pediatric patients with MPNs to build their knowledge base and comfort with medical decision-making.

An appropriate transition readiness assessment tool is a critical component of a high-quality HCT plan for young patients [18]. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) recognized the challenging nature of HCT for those with hematologic conditions, and developed readiness assessment forms for general hematology use, hemophilia care, and sickle cell disease care. The general hematology assessment tool served as a base for the development of the MPN-focused assessment tool, and the extensive experience of the panel caring for young patients with MPNs allowed for the translation of that form to include the MPN-specific elements. It will be important going forward to have young patients trial the form and provide feedback.

Another central aspect of HCT for both patients and caregivers to be considered is that of psychosocial development and support systems. It is important to include discussions and assessments related to various topics, including home environment, mental health, education/employment, sexuality, and substance use. There are various existing tools for providing frameworks and questions to guide these conversations, such as the HEADSSS assessment, which can support the educational and readiness assessment tools provided here. Involving a multidisciplinary team to support families through HCT, including social workers and psychologists, has been shown to be an important part of the HCT process [26], and can help support families in the transition from caregiver medical management to young patient medical self-management. Patient advocacy groups can also be a good resource for families, both for education and for providing a sense of community.

While there are consensus guidelines for the management of MPNs [27, 28], there are none focused specifically on young MPN patients [1]. Therefore, the panel felt that providing some consensus points regarding the care of young MPN patients would be extremely valuable for practitioners. These recommendations are based on expert opinion, knowledge of the literature, and significant clinical experience, and can be helpful both in providing some basic guidance for pediatric clinicians with limited experience caring for children with MPNs and in allowing for more continuity between pediatric and adult practices that might ease some of the strain associated with HCT.

One key diagnostic point the group agreed on was having bone marrow at diagnosis for a young patient with an MPN. Diagnostic criteria for MPNs may not be appropriate for children [29] and given increased rates of triple-negative ET [1], bone marrow is necessary for confirming an MPN diagnosis and determining the MPN type. There are no data to support ongoing, routine marrow re-evaluations in young patients who have stable labs and clinical findings and are not on cytoreductive therapy, so this was not recommended. Given that splanchnic thrombosis is not rare in young MPN patients [1, 2, 8], the panel felt a baseline abdominal ultrasound to assess liver and spleen size and splanchnic vessels was appropriate.

An additional focus of importance for the consensus statement was around the use of cytoreduction. The European LeukemiaNet MPN management recommendations state that cytoreduction should be started for patients with PV or ET who have a platelet count over 1500 × 10E9/L [27]. Young patients have lower rates of hemorrhage than thrombosis, and there are no data that higher platelet counts in children make them at higher risk, so similar to other recommendations [4, 30], the panel felt strongly that there is no specific platelet count to use as the indication for starting cytoreduction. In addition to thrombotic or serious hemorrhagic events as triggers for using cytoreduction, the panel felt that disease control and modification were important considerations. IFN has been used successfully in many young patients [1, 31], and there are compelling data in younger adult MPN patients that IFN use can extend myelofibrosis-free and overall survival [19–21, 32]. This is especially relevant for pediatric patients who will be living with their disease for many decades. Therefore, the panel felt that discussing the potential disease-modifying benefits of IFN with young patients was important and its use for this purpose should be considered. Future studies and formal guidelines for the management of MPNs in young patients would be of great value to the field.

When discussing the limitations of this work, the first consideration is our study team, as only a small number of physicians were included. Partnering with additional clinicians to identify gaps in the educational checklist and identify challenges to utilizing it in practice will be an important next step. The ASH general hematology transition readiness assessment form that was adapted for MPN patients was originally developed with the help of both pediatric and adult hematologists and a psychologist with transition expertise. Additional team members who would be valuable in a formal evaluation of our readiness assessment tool include statisticians and developmental experts with questionnaire development experience. Partnering with patients and families to pilot the tool and debrief in interviews or focus groups will allow for assessments of clarity and ease of use. In addition, prospectively evaluating the impact of the toolkit on patient satisfaction and outcomes after HCT has occurred will be an important future step.

With increased awareness of MPNs in younger patients, and a clear understanding of the importance of HCT, it is imperative to develop an effective process for HCT from pediatric to adult care. Our team took the first step toward this goal by developing a toolkit to help streamline the HCT process for AYAs with MPNs. More work is needed to further enhance and implement the use of these resources in the MPN community and evaluate their impact on the HCT process for our young MPN patients.

Author Contributions

N.K., M.G., and J.J.K. designed the study. All authors served as panel members and participated in the conduct of the study and development of the components of the toolkit. N.K. drafted the manuscript and all authors provided critical review and revisions. All authors approved of the final draft of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

N.K.: Consultancy—PharmaEssentia, Protagonist Therapeutics; Conference speaker—AOP Health. M.G.: Consultancy—AOP Health, Novartis, BMS, AbbVie, Pfizer, Roche, Jannsen, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Sierra, Lilly, GSK; Honorarium—AOP Health, Novartis, BMS, AbbVie, Pfizer, Roche, Jannsen, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Sierra, Lilly, GSK. J.J.K.: Consultancy—Novartis, GSK, AOP Health; Advisory board: BMS, Incyte, Abbvie, PharmaEssentia.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.