Communicating a Pediatric Leukemia Diagnosis to a Child and Their Family: A Qualitative Study Into Oncologists’ Perspectives

ABSTRACT

Background

A pediatric cancer diagnosis is overwhelming and stressful for the whole family. Patient-centered communication during the diagnostic conversation can support medical and psychosocial adaptation to the disease. Treatment of pediatric leukemia has become increasingly complex and requires a specific skillset from clinicians in effectively conveying information to families. The objective of the current study was to gain insight in the experiences and perspectives of pediatric oncologists when communicating leukemia diagnoses to families.

Procedure

In this exploratory qualitative study, oncologists were eligible to participate for each diagnostic conversation between May 2022 and February 2023 of families participating in a larger study. Twenty-six semi-structed interviews with 16 oncologists were thematically analyzed.

Results

Two interrelated conversational goals were identified: (i) informing the family about the illness, prognosis, and treatment; and (ii) creating trust and comfort for the family implying they are in the right place for maximal chance of survival. Oncologists experienced a challenge in balancing a high amount of information provision in a short timespan with simultaneously monitoring the (emotional) capacity and needs of the family to process information. Remarkably, oncologists commonly seem to rely on intuition to guide the family through the diagnostic conversation. They mentioned to sometimes postpone answering to family-specific informational needs and prioritized information they assume to be more helpful for the family at that time.

Conclusions

During diagnostic conversations, oncologists aim to convey information they assume supports the needs of the family. Future research should investigate how these communication strategies are perceived by families.

Abbreviations

-

- ALL

-

- acute lymphoblastic leukemia

-

- AML

-

- acute myeloid leukemia

1 Introduction

Even though survival rates have increased for pediatric leukemia, the life-threatening condition and intense treatment protocols with accompanying side effects can induce distress in patients and their parents [1-3]. High-quality communication is essential in supporting patients and families throughout the cancer care trajectory [4-6]. A key element of high-quality communication is the ability to monitor and adapt to family needs, which varies amongst parents and children [5, 7–12]. The first opportunity for high-quality patient–provider communication is during the diagnostic trajectory. Studies show that patient-centered communication can support family adjustment to a pediatric cancer diagnosis and enhances the establishment of the therapeutic alliance, hope, and trust [13-15].

Several core functions of patient-centered communication have previously been defined: exchanging information, responding to emotions, managing uncertainty, fostering healing relationships, making decisions, enabling self-management, providing validation and supporting hope [5, 16, 17]. While some domains are studied extensively in pediatric oncology, such as exchanging information, some gaps are identified for other domains, such as managing uncertainty and responding to emotions [18]. The latter is extremely relevant as parents and children go through a stressful and emotional time around diagnosis, which can influence information uptake and decision-making [12, 19, 20]. Additionally, the treatment of pediatric leukemia has become increasingly complex, which requires a broad skillset from clinicians in effectively conveying medical information to children and their families [21].

Studies that delve into how oncologists experience and approach the diagnostic conversation are still scarce [22, 23]. One study [24] focused on the preparation, content, and logistics during the diagnostic conversation rather than the explanation on how oncologists try to convey information. This study showed that while existing evidence claims that parents prefer to know prognostic information, the majority of oncologists normally do not mention prognosis during diagnostic conversations. Insight in the current state of communication during the diagnostic trajectory through how oncologists tackle this conversation helps to identify potential gaps in efficient communication and may support the development of educational material to further optimize diagnostic conversations in pediatric leukemia. Therefore, this study aimed to gain insight in the experiences and perspectives of oncologists while communicating a leukemia diagnosis to a child and their family.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

This qualitative study was part of a larger project named Communication Of a New diagnosis and Treatment to A Child and Their parents (the CONTACT study) aiming to observe and evaluate family–provider communication during diagnostic conversations in children (aged 0–19) with leukemia. For the current paper, we explored and thematically analyzed the pediatric oncologists’ perspectives using semi-structured interviews. Methods and results are presented according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist [25].

2.2 Sample

A purposive sample of pediatric oncologists working at the hemato-oncology department of the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology (Utrecht, the Netherlands) were approached to participate in this study. Pediatric oncologists were eligible to participate when they (i) had communicated a pediatric leukemia diagnosis as the treating oncologist of a family who consented to participate in the CONTACT study; and (ii) provided consent themselves to participate in the CONTACT study. Pediatric oncologists were recruited for an interview about their perspectives after each individual diagnostic conversation. Maximum variation was aimed for with respect to gender and age of pediatric oncologists and with regard to characteristics of the diagnostic conversation (age/gender child, attendance in conversation).

2.3 Procedure

The study was classified as exempt of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act by the institutional medical ethics review board (number 22-019). Participation in the study was voluntary, and the study was approved by the institutional ethical committee. The PhD student (P.B.) introduced the research project at a staff meeting and before introducing the informed consent to participants individually. After obtaining informed consent, semi-structured individual interviews were conducted between June 2022 and February 2023. Interviews took place within 2 weeks after the diagnostic conversation, and were performed at the preferred time and location of the pediatric oncologist and were conducted by a trained qualitative researcher (P.B.). Interviews started with an open question to invite the pediatric oncologists to share their experiences: “How did you prepare for this diagnostic conversation?.” Follow-up questions were based on literature on patient-centered communication and expertise of the research team [5]. Further along in the study trajectory and during interim data analysis, more in-depth interview questions were added to the interview guide. Data collection continued until saturation was reached.

2.4 Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and pseudonymized. A thematic approach based on the Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven was adopted [26]. The analysis team consisted of researchers trained in qualitative research (P.B., R.A., D.Z.), a senior researcher and health psychologist (S.S.), and a former pediatric intensive care nurse and senior qualitative researcher (M.K.), ensuring researcher triangulation. The first interviews were individually read intensively, open-coded, and discussed by a part of the analysis team (P.B., S.S., M.K.). This was done during the data collection, with the aim to develop a preliminary code tree. Subsequently, interviews were coded and categorized (by P.B., R.A., D.Z.) in Nvivo (QRS International Pty Ltd., Version 14, 2023). During the analysis process, context summary sheets and narrative reports facilitated discussion and validation within the analysis team. Several times throughout analysis, preliminary results were evaluated and discussed within the larger multidisciplinary research team of the CONTACT study team (P.B., S.S., M.K., two pediatric oncologists [P.H., N.D.], a principal investigator in psycho-oncology [M.G.], and a clinical psychologist [E.B.]).

3 Results

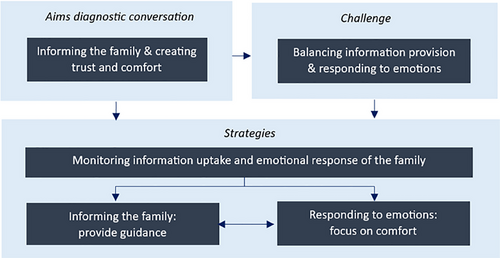

A total of 18 oncologists were eligible to participate. One oncologist did not provide informed consent, and one oncologist was unable to participate due to logistical reasons. In the end, 26 interviews with 16 oncologists (response rate 89%) reflecting the diagnostic conversations of 26 children with pediatric leukemia were thematically analyzed. Characteristics of the interviews, oncologists, and the diagnostic conversation are presented in Table 1. Based on the data acquired from the interviews, we identified the pediatric oncologists’ conversational goals, their experienced challenges, and the strategies they used to overcome these challenges (see Figure 1).

| Category or M | n | (%) or SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview characteristics | |||

| Gender | Male | 7 | (47) |

| Female | 9 | (53) | |

| Years of work experience in pediatric cancera | 0-10 | 6 | (38) |

| 11–20 | 4 | (25) | |

| 21–30 | 5 | (31) | |

| 31–40 | 1 | (6) | |

| Average years of working experiencea | 16.7 | 16 | 9.1 |

| Number of interviews conducted per PO | 1 | 8 | (50) |

| 2 | 6 | (38) | |

| 3 | 2 | (13) | |

| Setting | In person | 24 | (93) |

| By telephone | 2 | (8) | |

| Duration in minutes | 27 | 26 | 6 |

| Days since diagnostic conversation | 10 | 26 | 4 |

| Diagnostic conversation | |||

| Age of the child | 0-4 | 11 | (42) |

| 5–8 | 3 | (12) | |

| 9–11 | 5 | (19) | |

| 12–16 | 5 | (19) | |

| 16+ | 2 | (8) | |

| Average age of the child | 7.9 | 26 | 5.1 |

| Gender of the child | Male | 18 | (69) |

| Female | 8 | (31) | |

| Diagnosis | ALL | 23 | (92) |

| AML | 3 | (8) | |

| Attendance: family members | One parent | 1 | (4) |

| Both parents | 8 | (31) | |

| Both parents and child | 16 | (62) | |

| Only the child | 1 | (4) | |

| Attendance: other healthcare providers | 0 | 12 | (46) |

| 1 | 13 | (50) | |

| 2 | 1 | (4) | |

- Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; M, mean; n, sample size; PO, pediatric oncologist; SD, standard deviation.

- a Work experience in pediatric cancer from fellowship and onwards.

3.1 Conversational Goals

Oncologists generally entered the diagnostic conversation aiming for families to understand the illness, the fact that most children survive, the upcoming treatment, and what to expect for the upcoming days. Most oncologists mentioned an underlying goal behind the information provision: to create trust and comfort for the family to enable them to understand their new situation and to be able to keep going. Oncologists experienced several challenges in achieving these goals and described several strategies to overcome these challenges (see Table 2).

| Conversational goals: Informing the family and creating trust and comfort | ||

|---|---|---|

| PO | Quote | |

| Content | PO5 | “They need to know what is going on, they need to know that there was nothing they could have done to prevent this from happening, and they need to know that it is well treatable. These are the aims: they need to remember that after the first conversation” |

| Goal | PO8 | “In the end, I want that the patient, and also the parents obviously, have some idea what lies ahead of them in the short-term, mid-term, and overall. I hope this will gain more trust in the process and the outcome.” |

| Experienced challenges: Balancing information provision and responding to emotions | ||

|---|---|---|

| PO | Quote | |

| Responding to emotions | PO9 | “Naturally you just want to tell things and it is also difficult to have people crying in front of you. Yes, that continues to be difficult. It is very understandable, but difficult to get them out of it or to leave it as it is. It is always a moment to consider whether I should continue providing information or whether I should just stop and leave them for a moment. That is always a difficult consideration where I keep in mind that I want to have told certain things.” |

| Child withdrawing | PO6 | “He [child] seemed to be withdrawing and was not receptive to hearing more information from us. So we tried to talk with him separately to discuss the side effects of the medication and to discuss his own questions, but he was not open to it. We have respected that until now.” |

| Time pressure | PO4 | “You [oncologist] are basically just dealing with the issue that you have to pass on a lot of information, because you are starting treatment the next day. You have to explain things to parents, otherwise they get overstressed by everything that is happening to them. And also, you have to give them the patient information forms for treatment where it is all written down. And if you have not mentioned it before, they will think: ‘Well, he only said half of it, what is all of this?’ and then they become insecure. So it also causes a lot of distress if you do not tell them, with the risk that half of what you are explaining goes in the one ear and out the other” |

- Abbreviation: PO, pediatric oncologist.

3.2 Experienced Challenges of Oncologists

Even though oncologists mentioned the main message of the diagnostic conversation was the fact that most children survive, they also had to explain the intense treatment and side effects. Many oncologists reported that they felt urged to convey a lot of information in a very short timeframe, as treatment commonly started the same day and they wanted to prepare families for the upcoming days. At the same time, they mentioned that they were aware that this information could be distressing for the family and might not be processed or understood due to increased emotional burden (see Table 2 for exemplar quotes). During the whole conversation, oncologists tried to find a balance in conveying essential information and keeping parents and children engaged in the conversation by monitoring signals of information uptake and emotional distress in the family. This was even more challenging when the child was present during the conversation. Oncologists mentioned that parents could be more restrained in asking questions and showing their emotions when the child was present. Also, several oncologists mentioned that teenagers can be less prone in showing their emotions and can withdraw during the conversation. Both situations made it more difficult to observe whether information is still being processed or not. Most oncologists explained they felt the time pressure to make sure the family is well-prepared for what is going to happen during the upcoming days. One oncologist explicitly mentioned it can also cause distress in families when they are not well informed before the start of treatment, which can damage trust. Therefore, many of them also found it difficult to decide to either stop the conversation and continue at a later moment in time or continue the conversation.

3.3 Communication Strategies of Oncologists

Oncologists provided a variety of strategies to create balance in the child's and parents’ processing of information and management of emotions. First of all, oncologists mentioned they constantly monitored the information uptake and emotional distress of the family. When families were too emotionally distressed to process and understand the information, oncologists reported they focused more on providing trust and comfort. When oncologists believed the family was emotionally capable to process information, they provided direction for the family and focused on making sure the family understood the information that they believed was most helpful for them. The next section will elaborate on these three themes.

3.3.1 Monitoring Information Uptake and Emotional Response of the family

All oncologists mentioned they constantly monitored both verbal and nonverbal signs reflecting the information uptake as well as the emotional distress (see Table 3 for exemplar quotations). The majority of oncologists mentioned that they monitored the emotional distress by observing families’ facial expressions and body language to make an estimation whether they could still process information. Most oncologists reported that they used the questions posed by the family in order to estimate whether the family understood the information. Some oncologists mentioned that when they were in doubt whether the information was still processed based on observing the nonverbal expressions of the family, they checked with the family if the information was enough for now or if they should continue with providing information. Nevertheless, the estimation of the family's ability to process information and the decision to continue providing information was described to be mostly based on intuition. Interestingly, almost no oncologist mentioned they verbally validated the emotional distress with the family during the conversation, and one oncologist mentioned explicitly that he does not ask how the family is feeling during diagnostic conversations. On the other hand, all oncologists described to be observant of emotional distress, and described how they acted upon these emotions. The latter is presented in the strategies below.

| Monitoring Information uptake and emotional response of the family | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strategies | PO | Quote |

| Observe nonverbal expressions | PO12 | “I think it is hard to say, it is mostly body language, a feeling whether they want to continue with the conversation. Sometimes you also have to say, I think this is enough for now and I will be back tomorrow. I think it is mostly nonverbal, it is hard to explain … It is also very intuitive.” |

| Evaluate questions by the family | PO7 | “Well, they mainly kept listening well, and they all had very good question and stayed on topic. You see some people who jump all over the place because they still have so many questions in their heads and they cannot think in a structured way. So, while you are talking about one subject, they suddenly have a question about something for in 2 years. So you know, they are clearly not focused on what you are talking about. Those kinds of things, you pick up on those signals and then you know that it is enough for now.” |

| Asking the family | PO4 | “I believe I have asked it once, I am not sure anymore, but I think I just asked it once to the mother if she wanted me to continue with the conversation or are there any things you want to know? And then I was a bit in doubt whether she was hearing what I was saying or if she was just dreaming a bit.” |

| Not asking about emotions | PO10 | “I did not explicitly ask about their emotions, like: ‘how does this affect you?’. I did not do that, I actually never do that, no.” |

- Abbreviation: PO, pediatric oncologist.

3.3.2 Informing the family: Providing Guidance

When oncologists felt the family was still (emotionally) capable of processing information, they described to guide the family through the information that they believed was most helpful for them (see Table 4 for exemplar quotations). As stated earlier, oncologists described to be aware of the fact that information might not be processed due to the emotional distress of the family. Therefore, oncologists described to use several strategies to make sure the family understood and remembered the most important information. For example, to make sure the family remembered the key messages they wanted to convey, oncologists explained to repeat and summarize important information. Similarly, most oncologists mentioned they preferred to divide the information over different conversations, as that creates the opportunity to repeat information and summarize the most important information. Most oncologists mentioned they used visual support to facilitate understanding. This was either a piece of paper and a pen to draw some explanations when talking to the family, or a pre-printed treatment schedule. Additionally, most oncologists described they adapted the manner of providing information based on the context of the family. They used different words for families with different educational or literacy levels, and used examples that are relevant for the family. Some oncologists preferred to align their communication with the informational needs of the family (e.g., information the family is asking for) to guide the conversation. Others mentioned they tried to guide the family through the information they think was most helpful for them at the time and for this reason delayed providing the information the family was asking for. Oncologists explained that during the diagnostic conversations in pediatric leukemia, in general, few decisions regarding the treatment itself need to be made in collaboration with the family. However, some logistical aspects do require decisions. Some oncologists described they preferred to make these decisions for the parents based on what they feel that the parents would want. The latter was to protect the parents and child from too much burden.

| Strategies | PO | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Adapt words to health literacy or age-appropriate level | PO16 | “You have to find a way to communicate with each other. And that has something to do with the level at which you communicate: are you communicating with a medical student or colleague, that is different compared to when parents have a low literacy. It has something to do with finding the right words, such that we understand each other.” |

| Use relevant examples | PO14 | “I think if I would have known that he participated in car-racing, then you start using that as an example to say: you will have very low platelets, which means that you get bruised very easily or bleed more extensively and that it could be dangerous to do stuff like that” |

| Provide summaries | PO10 | “I try to finish the diagnostic conversation with two or three take-home messages: it is a life-threatening disease, we have to treat it, but we can also cure it.” |

| Repeat important information | PO6 | “I try to emphasize that it is a lot of information and that it is not weird that we have to repeat some information and that sometimes we say things multiple times” |

| Use visual support | PO9 | “Then I explain what leukemia is: that they are rapidly dividing cells of an early precursor in the bone marrow and then I draw that. I can also explain that chemotherapy targets that, so it makes the conversation easier when you draw it.” |

| Align with family needs | PO13 | “Well, when parents start asking questions like ‘What does the treatment look like exactly?’, What will you do tomorrow?’, or ‘What medications will he receive?’, it is clear that they have a need for more information. [Patient's] parents started asking these kind of questions, so I started explaining the treatment plan for the upcoming days.” |

| Set own agenda | PO5 | “Obviously, a lot of people want to know the logistics, appointments, how things will progress in the long term, for example regarding vacation and school. Most of the time, I keep it a bit vague and suggest we will revisit those topics at a later moment and say: ‘let's talk about the first 4 weeks for now.’ To bring them back to the level where I think they should be.” |

| Making decisions | PO4 | “You do not have to literally present the choice to them. That can also be very threatening to parents, because it can come across as if the doctors really do not know what to do with their child anymore. I have learned my lesson with that in the past with shared decision-making —it sounds fantastic, but I think with shared decision-making, that the doctor decides, because otherwise the parents have to carry the weight, but you decide what you feel the parents would want.” |

- Abbreviation: PO, pediatric oncologist.

3.3.3 Responding to Emotions: Create Trust and Comfort

Oncologists explained that when they observed that families became too emotionally distressed to process and understand the information, they either stopped the conversation or responded to these emotions by using strategies that are specific for creating trust and comfort (see Table 5 for exemplar quotations). Most oncologists explained that when emotions were prominent, they tried to create space for the family to process their emotions by using attentive silence. One oncologist even mentioned to wait for the family to start talking again before continuing the conversation. Next to this, oncologists tried to provide reassuring comforting information when emotions were prominent. That is, all oncologists mentioned that the main and most comforting message they wanted to convey is the fact that most children are cured and that the treatment is very effective. Moreover, oncologists tried to reassure the family that there is nothing the family could have done to prevent the child from becoming ill and that it would not have mattered if the diagnosis was detected earlier. They explained to the family that they intend to always be open and honest to the family. The latter was to avoid any suspicion in the family that the oncologist will hold certain information behind. The latter strategy was expressed to be especially important for teenagers when they were not attending the conversation. In that case, oncologists explicitly explained to the child that they would tell everything they also told the parents. They furthermore tried to build trust by showing the expertise of the hospital (and themselves) and by explaining that there is consensus throughout Europe about the standardized treatment protocol that is followed. Some oncologists mentioned that an empathic response and understanding that the family is going through a really difficult time was important in creating trust and comfort during the diagnostic conversation. Some oncologists indicated they explicitly mentioned their role and availability during the trajectory of the child: they will be the families’ main contact person and there is always someone they can reach out to for support or questions.

| Strategies | PO | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Stop conversation | PO14 | “It was definitely enough. And you could see this more in posture compared to words, I think. At some point we also said that we think it is enough for now.” |

| Focus on increased comfort | PO4 | “The more nervous and confused they are, the shorter I keep the first conversation, because otherwise they just do not process the information. With those people, I focus on other things: I focus on making sure they get some comfort and calmness.” |

| Give space for emotions | PO6 | “I think I tried to make some space for the emotions, so by letting it be there. I think that was the right thing. I think it is my thing to create some space for the emotions and let them show their emotions and then continue the conversation. At some point I felt there was a lot of emotion, so I should just not talk right now.” |

| Provide reassuring information | PO11 | “I always try to nuance it a little bit, so I often say that chemo is not like in the movies, it is not that your child is only extremely ill. It obviously depends on what type of conversation you have, but I believe that with an ALL-patient you can calmly say that a child will not get deathly ill, and it can vary between therapies, but we can also provide medicine against sickness … But that with this therapy you really can get better.” |

| Transparency | PO14 | “I say that I am not going to hold things back, definitely with teenagers, I will not hold things back or tell things differently. And this definitely helps with teenagers. They are sometimes afraid that they are protected, and they become a bit suspicious.” |

| Expertise | PO4 | “And that is why I always tell, like I did in this conversation: a lot of people will shout out a lot of stuff, but we [the oncologists] really know. Also to give them some trust that we are not a bunch of amateurs.” |

| Empathy | PO15 | “I think that an emotional reflection is important, to show some sort of compassion or that you know that they are going through a very tough time” |

| Explaining role and availability | PO2 | “I think I gain the most trust by telling they are going to see me all the time at the outpatient clinic, that they get all the phone numbers and that they can always call for every doubt: day and night and that is what we are here for. I think that is how I try to give them trust and for the other things you need time.” |

- Abbreviation: PO, pediatric oncologist.

4 Discussion

This qualitative study shows that during diagnostic conversations in pediatric leukemia, pediatric oncologists aim to inform families about the diagnosis and treatment and to establish trust and comfort to ensure families feel that they are at the right place for care and survival. Oncologists struggle in finding a balance between the provision of detailed medical information in a short timeframe and the emotional distress of the family given the situation and in response to this information. During the conversation, they carefully judge the family's ability to process information, often adjusting the pace, duration, and content of the conversation based on emotional cues and perceived understanding of the family. Additionally, oncologists use a variety of communication strategies to manage different informational needs and emotional responses within the family, ensuring that all family members receive appropriate and comprehensible information.

One of the key messages oncologists want to provide is the fact that most children survive. At the same time, oncologists need to convey information on the intense treatment protocol and corresponding side effects, which is overwhelming and stressful for the family [1-3]. Results show that oncologists respond to emotions by creating space for emotional expression by using silence, an empathic response, or shifting to strategies that are more focused on creating trust and comfort, such as providing reassuring information. Our results show that while oncologists mentioned to pay much attention to implicitly monitoring emotional cues and responding to those cues, almost no oncologist mentioned to explicitly explore or ask about the emotional distress of the family during the diagnostic conversation. This raises the question whether families would appreciate being explicitly asked about their emotions. Studies show that parents might want to downgrade their emotions during conversations with their healthcare provider in order to be an equally competent partner during the conversation or to provide comfort and safety for their child [27, 28]. Similarly, parents might prefer to not show their emotions during diagnostic conversations so they do not burden the oncologists, who is crucial in their child's chance for survival [29]. Therefore, future research should explore what the specific emotional needs of families are during the diagnostic conversation in pediatric oncology.

Additionally, our study shows that oncologists sometimes postpone answering to questions of the family when they believe other information is more beneficial at the time. When family informational needs, such as questions about the long-term planning, diverge from the oncologists agenda, they often redirect the conversation toward information they believe is more helpful at this stage for the family. Previous studies show that acknowledging parental concerns is a core trait of healing communication [30]. Therefore, redirecting the conversation when parents try to gain information on a specific topic might not be the most helpful approach for the family. Previous studies in pediatric cancer showed that acquiring extensive information can serve as a coping mechanism for parents in order to feel control over the situation [31, 32]. However, another study also suggests that parents appreciate limited information provision that aligns with the family's capacity to process it [20]. Therefore, it remains uncertain how families of children with cancer perceive the dismissal of specific questions during diagnostic conversations.

In general, our study shows that oncologists try to align their communication and information provision to the emotional and informational needs of the family. However, this alignment is commonly based on the clinicians’ judgment and intuition rather than explicit verification with the family. This is in line with a framework suggested by Sisk and Dubois in which they claim that everyday clinical interaction is based on intuition, but can be influenced by reflections (e.g., based on rational thinking) on their clinical interactions. Healthcare providers seem to naturally want to protect patients from distress and provide guidance to the family to release the burden [23]. Nevertheless, their intuition might not always be right. Previous research has demonstrated that intuition can lead to discrepancies between the preference of families and presumed preferences of the family by healthcare providers [7, 33]. Therefore, it remains essential to educate oncologists that their intuition is not always accurate, encouraging them to be mindful of how their intuitive judgments influence their communication with families. These reflections can support oncologists to validate their assumptions with families during the conversation, for example, by explaining their reasoning for their preference to postpone discussing certain topics or to stop the conversation.

Translating these findings into the core functions of patient-centered communication as described by Epstein and Street, results show that some domains of patient-centered communication are prominent during the diagnostic conversation in pediatric leukemia, whereas others are less evident [5]. For the domain of exchanging information, results show that oncologists do not only want to provide information, but are also constantly monitoring whether the information is well understood. Regarding responding to emotions, physicians respond to emotions, though they do not always explicitly inquire into the emotional experiences of both parents and children. Managing uncertainty is addressed to some extent, with efforts made to reduce uncertainty where possible by explaining what the short-term will look like and to guide parents to what to prioritize regarding information exchange. The two domains specific for pediatric oncology, supporting hope and providing validation are strong aspects during the diagnostic conversation [17]. Oncologists explain to families that most children diagnosed with leukemia survive, which supports hope. The message that the family did nothing wrong in causing the disease validates good parenting. All of these domains together, next to all the strategies that are focused on creating trust and comfort, also represent the focus on fostering healing relationships during the diagnostic trajectory. Enabling self-management and making decisions were less prominent identified domains during the diagnostic conversation. Oncologists explained that not many decisions need to be made regarding treatment with the parents of child during the diagnostic conversation, which is in line with previous research [34]. Additionally, enabling self-management might be a more prominent domain after the diagnostic conversation, towards the moment where families leave the hospital and go home.

This study offers valuable insights into oncologists’ experiences and perspectives during diagnostic conversations in the acute and stressful context of pediatric leukemia. Previous literature has mainly focused on content and logistics of diagnostic conversations rather than the perspectives and approach of oncologists. Given the short interval between the diagnostic conversations and the interviews, the findings represent communication challenges and strategies of that specific conversation. However, this study is also limited to the context of pediatric leukemia and may not be generalizable to other diagnoses with other, mostly longer, diagnostic trajectories and/or with less favorable prognoses. Additionally, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity among the families to which the oncologists had to disclose a diagnosis might limit generalizability to other cultural backgrounds.

To conclude, oncologists aim to provide comprehensive information about the diagnosis and treatment plan while fostering trust and comfort during diagnostic conversations in pediatric leukemia. A key challenge is balancing the provision of detailed medical information next to monitoring the emotional distress of families. Oncologists try to align their communication to the emotional and informational needs of the family. However, this alignment seems to be predominantly based on the oncologists’ judgment and intuition, which may not always align with the needs of the family. Therefore, it remains essential to educate oncologists to be mindful of how their intuition influences the conversation with families and be aware of the importance of validating their decisions with families. Future research should explore parental experiences during the diagnostic trajectory.

Acknowledgments

We thank all pediatric oncologists for participating in the study and sharing their experiences. Additionally, we want to express our gratitude toward Mieke Oorschot and Dennis Bot for their valuable assistance in transcribing the interviews. We also want to thank Janine Kops and Marjolein ter Haar for their valuable reflections on the interview guide. This study was funded by the Irenestichting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.