Satisfaction and access to care for adults and adolescents with sickle cell disease: ASCQ-Me quality of care and the SHIP-HU study

Abstract

A lack of adult sickle cell providers has long been blamed for poor satisfaction and access to specialty care for adults with sickle cell disease (SCD). We were interested in comparing how adolescent and adult patients already in established SCD centers perceived access and quality of care. Hydroxyurea-eligible patients aged 15 years and older were enrolled in the Start Healing in Patients with Hydroxyurea trial, which required them to be affiliated with a SCD specialist. Patients were seen in one of three adult-oriented specialty clinic sites or one of three pediatric-oriented sites. At baseline, patients completed the Adult Sickle Cell Quality of Life Measurement Information System measure as part of a survey battery. Patients treated at adult clinic sites reported being less able to get timely ambulatory appointments (p = .004). They reported emergency department (ED) wait times of >1 h far more often (47.7 vs. 19.3%, p = .0048). They reported less overall satisfaction with care (7.47 vs. 8.77, p < .0001), and less satisfaction with care in the ED (2.88 vs. 3.4, p = .0068. Ambulatory satisfaction was no different between pediatric site versus adult site patients. Poorer systems of care appeared to underlie reported differences, rather than differences in biopsychosocial determinants. Even among specialty-care-affiliated SCD patients, those seen in adult clinics reported worse access to care and lower satisfaction with care than patients seen in pediatric clinics. In addition to increasing the number of adult SCD providers and better preparing pediatric SCD patients to transfer to adult programs, SCD clinical caregivers must also improve aspects of adult care quality to meet reasonable patient expectations of timeliness and interpersonal aspects of care quality.

Abbreviations

-

- ASCQ-Me

-

- Adult Sickle-Cell Quality of Life Measurement system

-

- AYA

-

- adolescent and young adult

-

- ED

-

- emergency department

-

- HU

-

- hydroxyurea

-

- MHC

-

- medical history checklist

-

- QoC

-

- quality of care

-

- SCD

-

- sickle cell disease

1 INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD), a set of genetic erythrocyte disorders affecting persons of African, Mediterranean, or Asian descent, was first described in 1910.1 As a result of dramatic improvements in care,2, 3 the vast majority of patients survive to adulthood so that there are currently more adults than children living with SCD in the United States.4 Despite this, adult SCD care in the United States is sorely lacking. Studies of access to care and utilization for adults with SCD compared with children using administrative databases find that transition-age patients and young adults have both higher emergency department (ED) utilization rates and unstable access to primary and subspecialty ambulatory care.5 A lack of adult SCD providers nationally has been blamed. Disparities in the availability of SCD care have been decried by national authorities6, 7 and have been blamed for the increased morbidity and mortality during the transition-of-care years, when adolescents and young adults (AYA) leave pediatric care and seek adult care. Further, morbidity and mortality continue at higher rates during adulthood8 again presumably due to lack of SCD specialty providers.

The quality of care (QoC) and the success of transition from pediatric to adult care for patients with SCD also lags, compared with the QoC for well children or those with other special health care needs.9-11 QoC indicators for SCD have only recently been proposed, published12 and/or measured, either for children13, 14 or for young and older adults.15-19 The first paper that outlined the necessary components of dedicated adult sickle cell treatment centers was only recently published6 and descriptions of patient reported experiences regarding QoC have only recently been published.20

We therefore were interested in comparing how adolescent and adult patients already in established SCD centers perceived access and QoC. We fielded a survey to test whether access to SCD care and satisfaction with SCD care were comparable when both pediatric and adult SCD specialty providers were available. We were interested in perceptions regarding timeliness of care, interpersonal aspects of QoC, and ratings of pain management, and whether they differed among adult versus pediatric centers. Further, we were interested not only in whether differences in these perceptions were reported, but also why they might be reported. We hoped to determine whether underlying structural differences in care were driving any reported differences in access and satisfaction by clinic type, versus differences in biopsychosocial determinants of perceived need for care. We were aware that disease severity and psychosocial need, both of which could drive patient perceptions, tend to increase in older patients and in those who require contact with the medical system more often, those more likely to be seen in adult clinics.

2 METHOD

2.1 Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from a randomized controlled trial, Start Healing in Patients with Hydroxyurea (SHIP-HU). SHIP-HU was designed to improve adherence to HU among HU-eligible (Hb SS or Hb SBeta0 Thalassemia) SCD adolescents and adults already cared for by SCD specialists. The study utilized informed consent and was approved by the VCU Institutional Review Board as well as the Institutional Review Boards of participating sites. All participants were aged 15 years or older at enrollment. Patients included in this analysis were those being cared for in one of four adult or three pediatric clinic sites. Top line results from this study have been published elsewhere. 21 All of the pediatric sites had established transition readiness programs in place that aimed to prepare patients for transfer to adult care.

2.2 Study sites

The SHIP-HU study enrolled patients at six clinical sites, three caring for adult sickle cell patients and three caring for pediatric patients with SCD. Five of the sites are housed in academic medical centers. One of the pediatric sites is community based. All centers were in urban or suburban settings, and all but one was associated with level I trauma centers. All the sites reported that their EDs saw pediatric and adult patients in separate clinical facilities, and no center had a combined adult and pediatric emergency care space. Five sites reported that most of their patients sought care in their center's ED when needing acute care services. One site reported about half of their patients routinely sought care in their affiliated ED and the other half generally used outside emergency rooms.

With regards to outpatient care, all the sites offered 10–14 outpatient clinic sessions per week, defined as half-day clinics staffed by a single provider. There was no difference between appointment availability between the adult and pediatric sites, when the number of patients served was considered. The average wait time for routine appointments for established patients was less than 4 weeks during the enrollment period at all centers. Most centers reported that visits were routinely available in less than two weeks. Four of the six centers had outpatient infusion centers available to established patients, including all three pediatric sites and one of the adult sites. One adult center and two pediatric centers reported that infusion services were available every business day. The third pediatric site reported infusion services were available 3 days per week.

2.3 Assessment

Patients were assessed by trained research assistants blinded to patient assignment. As part of the baseline survey battery, patients completed scales from the Adult Sickle-Cell Quality of Life Measurement system (ASCQ-Me).22-24 ASCQ-Me was developed to describe the impact of SCD on the health and quality of life of individuals living with SCD.23 For this analysis, we used ASCQ-Me QoC measurement,24 which includes 27 items related to access to care as a quality metric in the ambulatory specialty and emergency room settings, as well as satisfaction measures in both of those clinical settings. It queries patients’ experience of QoC and communication in the ambulatory setting and the acute ED setting. Patients rate interaction with various staff in these settings, including providers, nurses, and reception staff. Patients report how quickly they can get care in the ambulatory and acute settings and on ED wait times. These item responses consist of a 4 or 5 item Likert scale. Additionally, the QoC survey queries self-reported utilization (quantity and quality) of ambulatory care and acute care. A final composite item queries overall satisfaction using a 0–10 Likert scale, with 10 being the most satisfied.23

In addition to ASCQ-Me QOC, patients completed the ASCQ-Me measures of emotional impact/distress, and the medical history checklist (MHC), a SCD comorbidity/complications measure as a proxy of disease severity.22 Social support was assessed with the multidimensional scale of perceived social support.25 We also collected patients’ age, race, HU use, gender, and confirmed genotype using hemoglobin fractionation at a central laboratory.

2.4 Analysis

We determined frequencies (percent) of categorical variables or means and standard deviations of continuous variables. We compared variables between groups using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables or ordinal variables. Analysis of covariance was used to control for social support as well as for ASCQ-Me MHC and emotional impact, when comparing groups for satisfaction outcomes. Outcomes for satisfaction related to ambulatory care also controlled for ASCQ-Me QOC quantity of visits, outcomes for satisfaction related to ED care also controlled for ASCQ-Me QOC quantity of ED visits, while the model for overall satisfaction with care included both quantity of ambulatory care visits and ED visits. An exploration of the effect of clinic, devoid of confounding effect of age on satisfaction used the subset of patients between the ages of 18 and 22 years, as these patients were seen in pediatric and adult clinics. Because the sample size was small (n = 26 each pediatric and adult sites), which would imply lack of power to detect differences, statistical inference was not performed (i.e., no p values presented).

3 RESULTS

A total of 224 patients aged 15 years and older were enrolled in the SHIP-HU study, but six were inappropriately randomized and were excluded. Another 34 provided no ASCQ-Me QOC data at baseline (n = 25) or were missing MHC (n = 9), leaving n = 184 for this analysis—54 treated at pediatric clinical sites and 130 treated at adult clinical sites. Generally, patients 18 and younger were cared for at pediatric sites, and patients older than 21 were seen in adult sites. However, young adults between the ages of 18 and 22 years were evenly split between pediatric and adult sites. Table 1 shows there were no statistical differences between pediatric versus adult site patients with regards to gender, genotype, HU use, social support, or number of ambulatory care visits. However, there was a statistically significant difference between pediatric versus adult site patients in SCD comorbidities and complications: patients treated in adult sites had a higher mean MHC score of 2.2 versus a mean score of 1.1 among those treated in pediatric sites (p < .0001) and more ED visits (for example, 23.4% at adult clinics vs. 41.5% at pediatrics had no ED visits, and 28.9 vs. 9.4% had four or more ED visits). In addition, patients treated in adult sites had a lower (worse) mean emotional impact scale score of 51.6 versus a mean score of 56.2 among those treated in pediatric sites (p = .0006).

| Pediatrics (n = 54) | Adults (n = 130) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.9 (2.1) | 33.2 (11.4) | <.0001 |

| Age group | <.0001 | ||

| 15–17 | 28 (51.8) | 0 ( 0.0) | |

| 18–22 | 26 (48.2) | 26 (20.0) | |

| 23–30 | 0 ( 0.0) | 42 (32.3) | |

| 31+ | 0 ( 0.0) | 62 (47.7) | |

| Male | 21 (38.9) | 59 (45.4) | .4183 |

| HU user | 48 (88.9) | 100 (76.9) | .0624 |

| SS genotype | 50 (92.6) | 109 (83.8) | .1149 |

| SCD-MHC overall score | 1.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.5) | <.0001 |

| Social support | 62.6 (23.7) | 58.3 (27.6) | .3248 |

| Emotional distress | 56.2 (9.0) | 51.6 (7.7) | .0006 |

| #Ambulatory care visits | .3427 | ||

| 0 | 5 ( 9.3) | 10 ( 7.7) | |

| 1 | 3 ( 5.6) | 5 ( 3.8) | |

| 2 | 8 (14.8) | 19 (14.6) | |

| 3 | 8 (14.8) | 38 (29.2) | |

| 4+ | 30 (55.6) | 58 (44.6) | |

| # ED visits | .0068 | ||

| 0 | 22 (41.5) | 30 (23.4) | |

| 1 | 12 (22.6) | 16 (12.5) | |

| 2 | 6 (11.3) | 24 (18.7) | |

| 3 | 8 (15.1) | 21 (16.4) | |

| 4+ | 5 ( 9.4) | 37 (28.9) |

- a Presented as frequency (%) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables.

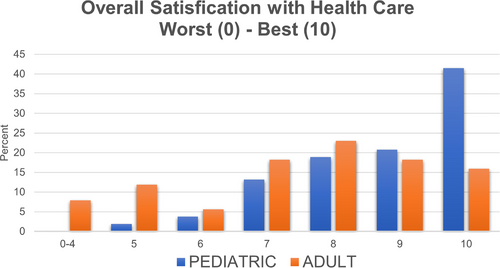

Regarding overall satisfaction with care, shown in Figure 1, on a scale of 0–10, satisfaction was significantly higher for patients treated in pediatric versus adult sites (mean 8.75 vs. 7.46, p < .0001). While 41.5% pediatric site patients reported their overall satisfaction with care was 10, only 17.8% of adult site patients scored overall satisfaction of 10. No pediatric site patients reported any value lower than 5, while 7.4% of adult site patients reported values of 0–4. When controlling for social support, ASCQ-Me MHC and emotional impact, and number of primary care and ED visits, the mean overall satisfaction values were similar to unadjusted values (8.51 vs. 7.55, p = .0059).

Table 2 outlines differences between pediatric site patients versus adult site patients with respect to satisfaction with ED care. On a 1–4 Likert scale, patients treated at pediatric sites reported statistically higher means on overall satisfaction with care in the ED (3.4 vs. 2.88, p = .0068), items querying whether their ED doctors or nurses cared about them (3.33 vs. 2.74, p = .0038; 3.33 vs. 2.77, p = .0053 respectively), whether their ED staff believed their pain (4.32 vs. 3.63, p = .0038) and whether their ED staff was able to help with their pain (4.26 vs. 3.67, p = .0131). The same relationships held when controlling for social support, emotional impact, MHC and number of ambulatory visits (3.35 vs. 2.74, p = .0047; 3.29 vs. 2.79, p = .0175, 4.38 vs. 3.61, p = .0015; 4.29 vs. 3.66, p = .0064, respectively) (Table S1).

| Pediatrics N = 54 | Adults N = 130 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often did the doctors treating you seem to really care about you? | 3.33 (0.18) | 2.74 (0.10) | .0038 |

| How often did the nurses treating you seem to really care about you? | 3.33 (0.17) | 2.77 (0.10) | .0053 |

| How often did the clerk/receptionist treat you with courtesy and respect? | 3.47 (0.15) | 3.15 (0.8) | .0711 |

| How often were you satisfied with the care you received? | 3.40 (0.17) | 2.88 (0.09) | .0068 |

| How much were the emergency room doctors and nurses able to help your pain? | 4.26 (0.10) | 3.67 (0.11) | .0131 |

| How much did the emergency room doctors and nurses believe that you had very bad sickle cell pain? | 4.32 (0.20) | 3.63 (0.11) | .0038 |

The majority of patients treated at both adult (68%) and pediatric (85.7%) sites reported that they were always satisfied with ambulatory sickle cell care (Figure S1). Table 3 outlines satisfaction with ambulatory care. Patients generally felt that their medical providers listened carefully, understood how sickle cell impacted the patient personally, and treated them with courtesy and respect. There were no statistically significant differences in any of these measures based on treatment site. However, patients cared for at pediatric sites reported significant higher overall satisfaction with scheduled appointments (3.70 vs. 3.43, p = .0399) as well as time spent with patient (3.80 vs. 3.56, p = .0281). These latter two significant relationships though were no longer significant after controlling for social support, emotional impact, MHC, and number of visits (3.58 vs. 3.47, p = .4346 and 3.77 vs. 3.58, p = .0933, respectively) (Table S2).

| Pediatrics N = 54 | Adult N = 130 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often were you satisfied with the care you received during these scheduled appointments? | 3.70 (0.11) | 3.43 (0.07) | .0399 |

| How often did this doctor or nurse explain things in a way that is easy to understand? | 3.64 (0.10) | 3.64 (0.06) | .9884 |

| How often did this doctor or nurse listen carefully to you? | 3.78 (0.09) | 3.71 (0.06) | .5023 |

| How often did this doctor or nurse treat you with courtesy and respect? | 3.85 (0.07) | 3.82 (0.04) | .7139 |

| How often did this doctor or nurse spend enough time with you? | 3.80 (0.09) | 3.56 (0.06) | .0281 |

| How much does this doctor or nurse know how SCD affects you personally? | 4.36 (0.15) | 4.11(0.10) | .1650 |

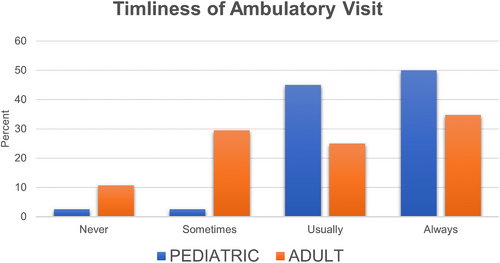

Access to care in both the ED and ambulatory settings was better for patients in pediatric sites versus adult sites. Pediatric site patients were more likely to be able to get timely ambulatory appointments when necessary (p = .004) (Figure 2). There was no difference between sites with regards to provider continuity at each visit, with approximately 95% of all patients reporting that they would see their usual provider when making ambulatory appointments regardless of clinical site. Access to ED care was measured by reported wait times (Figure 3). Fully 47.7% of patients in adult sites reported their longest wait times of >1 h, whereas only 19.3% of patients at pediatric sites reported wait times of >1 h (p = .0048). Of note, while 66.4% of adult site patients and 40.7% of pediatric site patients reported ever delaying or avoiding ED care, only 1.5 and 1.6% respectively of those reported delayed care due to concerns related to insurance, suggesting that insurance was not a significant barrier to care in this population.

To explore differences in site controlled for age, we analyzed the population aged 18–22 years as a separate group. These patients were evenly divided between pediatric and adult care sites (Table S3). Differences between patients seen at pediatric versus adult sites were more similar for MHC, social support, emotional impact, and utilization than for the full sample. We found no obvious differences between either access to care or satisfaction with care based on treatment site, with the data showing no numerical trend toward improved scores for patients seen at pediatric sites (Tables 4 and 5). Generally, differences between sites were diminished. Because the sample size was small, which would imply lack of power to detect differences, statistical inference was not performed (thus no p values presented).

4 DISCUSSION

We found, among patients with established care at pediatric or adult SCD clinics, differences in reported access to care and satisfaction with care, using a validated QOC instrument. Patients treated in pediatric clinics reported higher overall satisfaction with care as well as higher satisfaction with ambulatory and ED care. Similarly, patients treated in pediatric clinics reported better access to care, both ED and ambulatory care, than patients treated in adult clinics. The most striking differences seen between pediatric versus adult clinics were in access to ED care and satisfaction with ED care.

We controlled our results for the relatively worse reported comorbidity and complexity of SCD patients cared for in adult clinics based on the SCD-MHC score, for social support, and for emotional impact of SCD. ED utilization is known to be higher for patients treated at adult clinics5 and was reported higher for patients seen in adult clinics in our sample. This higher utilization, plus worse comorbidity in patients seen in adult sites in our sample, raised the hypothesis that SCD satisfaction with care and access to care in our sample declined simply as a function of perceived need, which was higher among older, more complicated patients. Controlling for MHC, social support, and emotional impact did not confirm this hypothesis, suggesting that the decreased access and satisfaction were instead related to differences in the care delivery systems themselves.

Findings of differences in SCD pediatric and adult access and quality usually blame two major barriers: lack of adult sickle cell providers and lack of appropriate insurance coverage. We acknowledge these barriers are important and impactful and must be addressed. However, in this study, few patients cited lack of insurance as a barrier to ED care.

Further, although increased age was likely associated with decreased access and QoC in both populations, the sample we studied had adequate structural access. All had an established relationship with an adult SCD expert who was part of a larger health care system. Limiting our investigation to this study sample forces us to explain our findings by postulating factors other than access to care. We conclude our findings are best explained by differences in the quality of systems of adult versus pediatric SCD care at the studied sites. Differences in comprehensive care, rather than differences in the outpatient hematology clinics or the SCD providers where patients received their specialty care, were reported by study patients.

Our results are consistent with those of the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium who administered the ASCQ-Me QOC to 440 adolescent and adult patients across 7 sites. Their population also scored low with regards to access to emergency care and satisfaction with ED visits and staff. They did not analyze patients by treatment site, but rather by age, and found that satisfaction was significantly higher for patients less than 19 years of age when compared to those older than 19 years of age.20

Our results force us to consider differences in the structure of pediatric versus adult SCD care. In all of the study's participating centers, pediatric sickle cell outpatient and acute care appeared to be more fully integrated such that pediatric SCD patients had a single care team during regardless of the clinical location. Pediatric ED care generally involved the pediatric SCD team early, seeking input and guidance from the providers who already had an established relationship with the patient. If patients were admitted to the hospital, they were cared for by a sickle cell specialist from their known practice group. This was not the case for participating adult sickle cell centers, where acute care in the ED or inpatient environment was largely carried out by providers without any specific sickle cell expertise and with minimal involvement of the SCD care team.

Our results have implications for adult SCD care. Patients with SCD are living longer. Yet there remains a lack of understanding about, comfort with, and acceptance of SCD adults by nonhematologist adult medicine specialists, including ED physicians and primary care physicians.26 Holistic integration of SCD adult care across all facets of the medical center may improve adult SCD care quality. Systems will need to focus on education and training of adult providers27 and must develop coordination-of-care teams that include adult SCD specialists. Additionally, systems need to implement evidence-based practice models to better serve this population. For example, EDs appear inferior to SCD-specific infusion centers or day hospitals to administer care for acute SCD pain.28 Such centers use individualized pain plans, standardized treatment pathways, and rapid analgesic titration algorithms for patients with SCD, and vastly improve the likelihood of timely analgesia and lower the likelihood of admission to the hospital. Additionally, they are staffed by medical providers with training and expertise in SCD. Even when similar evidence-based strategies to improve care are implemented in the ED, care in infusion centers appears to be superior.29 All of the pediatric patients in the SHIP-HU study had access to infusion centers as part of their sickle cell care. Only two of the clinical sites serving adults had an infusion center during the study period. While the tools used to assess satisfaction with care specifically asked about experience in the ED, this disparity may have contributed to our findings. This is one example of the differences in the pediatric and adult systems of care in this particular study.

Our study has some limitations. Chief among them, the SHIP-HU study used ASCQ-Me for the evaluation of adolescent patients ages 15–18. The ASCQ-Me QOC questionnaire was not validated in this age group. It has been used by other groups to assess QoC.20 However, it cannot be assumed that all ASCQ-Me measurements are appropriate for use in adolescent patients. Future work could validate the ASCQ-Me tools in the adolescent population. This could be particularly helpful in defining successful health care transitions in this high-risk population. A second limitation of our study is that it did not include patients seen primarily outside of SCD specialty centers. Extrapolation of these results to patients seen in more remote settings requires further investigation.

Finally, in an attempt to control for age, we analyzed a small group of AYA patients split between pediatric and adult centers finding no numeric difference between accesses to care or satisfaction to care based on treatment site. However statistical power was insufficient to determine whether site differences might exist for this group. We also recognize that the transition age group may not be fully representative, given their unique position. Although many of these patients have established care with an adult sickle cell provider, they are just starting to learn the complex and very different adult system of care. As a result, we cannot fully differentiate between the effect of age and the effect of treatment site on our results for this population.

We conclude that, while future work is necessary to define quality metrics and program structure for adult care, recent calls for improved access to SCD care and improved SCD care quality are valid and apply to all adult providers.7 It also highlights a potential fallacy of transition-of-care programs in SCD—the idea that the main goal of the pediatric SCD provider is to educate adolescents and then find a willing adult SCD provider. Simply moving a patient to an adult system of care does not guarantee the quality of that care. Instead, our findings support calls for improved QoC of patients seen in adult SCD clinics and suggest there is much systematic work to be done.6 Perhaps such changes would encourage more providers to create centers of excellence for adults with SCD, where comprehensive support systems are in place to ensure excellent quality care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The SHIP-HU Study, Enhancing Use of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Disease using Patient Navigators, is supported through NHLBI IR18HL112737 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Registered with Clinicaltrials.gov NCT# 02197845.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data collected in this study are available from the authors, and because the study was funded by NHLBI, are public domain. They are not yet available in BioLinCC, NHLBI's biologic specimen and data repository information coordinating center that is free to the public [https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/], but should be within the next 2–3 years.