How effective are behavioral interventions to increase the take-up of social benefits? A systematic review of field experiments

[Correction added on 2 April 2025, after first online publication: The third author's name has been corrected from ‘Alexandre Fortin-Chouinard’ to ‘Alexandre Fortier-Chouinard’.]

Abstract

Non-take-up of social benefits is a significant policy issue caused by factors such as lack of awareness, compliance costs, and stigma. While public information campaigns, default options, and in-person assistance are increasingly used, their effectiveness remains poorly understood. This study provides a systematic review of field experiments evaluating nudges and simple behavioral interventions on program take-up. We analyzed 93 interventions from 35 studies published over nearly 20 years, predominantly focusing on major U.S. programs. We compared study characteristics, including sample and intervention types, and assessed study quality. Due to high heterogeneity, we did not conduct a meta-analysis but used forest plots and thematic summaries instead. Most studies reported a positive impact on program take-up, but not on program application. Two types of interventions were notable for their impact on program application and take-up: 1) providing and framing information; and 2) providing assistance. We discuss the limitations of this review, including the cost and safety of nudges and the implications of focusing on field experiments. We conclude that further research is needed on simpler interventions outside the U.S., as well as on compliance and psychological costs. Additionally, improving the quality and transparency of field experiments is essential.

Non-take-up—the phenomenon where individuals do not receive the public services or social benefits they are entitled to—is pervasive across the globe (Chudnovsky & Peeters, 2021; Daigneault, 2023; Eurofound, 2015). This issue can lead to policy failure, increased inequality, poverty, and social exclusion (Daigneault, 2023; van Oorschot, 1991). While it affects all programs, means-tested benefits for low-income individuals are particularly vulnerable to non-take-up (Currie, 2004; Eurofound, 2015; Szeintuch, 2022).

While the causes of non-take-up are complex, simple behavioral interventions show promise to mitigate this issue (Bertrand et al., 2006; Herd & Moynihan, 2018; Van Gestel et al., 2023; Weaver, 2015). These include public information campaigns, in-person assistance, and leveraging psychological insights to nudge individuals towards program application. Scholars and practitioners increasingly evaluate these interventions through field experiments—the gold standard for assessing the effectiveness of administrative practices in real-world settings (Arceneaux & Butler, 2016; Bækgaard et al., 2015; Doberstein, 2017; Hopkins & Dorion, 2024; Jilke et al., 2016). However, our understanding of whether behavioral interventions generally increase the take-up of social benefits remains limited.

We address this research gap through a systematic review. This review contributes to the literature by systematically analyzing field experiments on the effectiveness of behavioral interventions in increasing social benefits take-up and by identifying existing research gaps. This article is structured into four sections. First, we discuss the significance of non-take-up and its causes, highlighting administrative burden, along with the potential of behavioral interventions to mitigate this issue. Second, we explain our review approach and methods. Third, we present the results of our systematic review, detailing the characteristics and findings of the included studies. Fourth, we discuss the implications and limitations of these results for understanding non-take-up and the effectiveness of behavioral interventions, concluding with a research agenda.

NON-TAKE-UP, ADMINISTRATIVE BURDEN, AND BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Non-take-up represents a significant, multifaceted policy problem. From a policy perspective, it may lead to policy failure, as the intended positive impacts on knowledge, attitudes, behavior, or material circumstances will not materialize if eligible individuals do not use public programs (Daigneault & Macé, 2020; Herd et al., 2023; Rossi et al., 2004). Additionally, non-take-up may indicate that social programs do not meet the needs of the target population, suggesting a need for program redesign (Lucas et al., 2021; Warin, 2012).

Non-take-up is also problematic from a social rights perspective (van Oorschot, 1991). For instance, “non-receipt”—when citizens are unduly denied benefits required by law (Warin, 2016, as cited in Daigneault & Macé, 2020)—is a breach of procedural justice, albeit an injustice that cannot be corrected by behavioral interventions. Beyond procedural justice, non-take-up has normative implications for distributive justice. While non-take-up is not problematic when individuals make a free and informed decision not to apply, it becomes an issue when it is involuntary due to lack of program awareness or “non-knowledge.” This can lead to illegitimate disparities in outcomes (Daigneault, 2023; van Oorschot, 1991). Disparities are also problematic when individuals need and want programs but do not apply due to confusing eligibility rules, stressful application processes, or stigma (Brodkin & Majmundar, 2010; Daigneault & Macé, 2020; Heinrich et al., 2022; Herd et al., 2013; Janssens & Marchal, 2022; Lasky-Fink & Linos, 2022).

Vulnerable groups are particularly affected by both the costs of interacting with the state to access social benefits and non-take-up (Bell et al., 2023; Christensen et al., 2020; Currie, 2004; Döring & Madsen, 2022; Herd & Moynihan, 2018; Herd et al., 2023). Moreover, non-take-up can reinforce existing socioeconomic inequalities, increasing the risks of poverty and social exclusion (Daigneault, 2023; van Oorschot, 1991). Ultimately, non-take-up may lead to resentment, distrust, resistance, or political disengagement, damaging the democratic bond (Bell et al., 2023; Daigneault, 2023; Daigneault et al., 2024; Lucas et al., 2021).

Non-take-up is complex and influenced by various institutional and individual factors (Daigneault et al., 2012; Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022; van Oorschot, 1998). Individual factors include the financial value and duration of benefits, the sense of stability in potential beneficiaries' lives, and their perceived need for the program (Currie, 2004; Gibson & Weisner, 2002; Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022). Scholars increasingly emphasize the role of administrative burdens in causing non-take-up (Christensen et al., 2020; Daigneault, 2023; Fox et al., 2023; Heinrich et al., 2022; Janssens & Marchal, 2022; Negoita et al., 2022). Administrative burdens refer to situations where individuals perceive policy implementation as onerous (Burden et al., 2012). Specifically, citizens encounter three types of costs when interacting with the state (Moynihan et al., 2015; but see Daigneault, 2024, 2025). Learning costs arise from acquiring information about public programs and evaluating their relevance, and often result in non-take-up (Barnes & Riel, 2022; Daigneault & Macé, 2020; Gibson & Weisner, 2002). Compliance costs arise from fulfilling programs’ rules and requirements such as providing documentation, completing forms, and waiting in line. The burdens associated with applying for a program, adhering to its rules, and interacting with street-level bureaucrats contribute to increased non-take-up rates (Brodkin & Majmundar, 2010; Chudnovsky & Peeters, 2021; Herd et al., 2013). This finding is consistent with the economic literature on targeting, ordeals, and hassle costs (e.g., Alatas et al., 2016; Bertrand et al., 2006). Psychological costs include stress, stigma, and feelings of powerlessness resulting from interacting with the state. Stigma in particular can discourage individuals from claiming benefits (Baumberg, 2016; Lasky-Fink & Linos, 2022; Stuber & Kronebusch, 2004).

Political decision-makers may intentionally impose rules, procedures, and processes that create significant administrative burdens (Herd & Moynihan, 2018; Peeters, 2020). This can serve as a deliberate strategy to limit access to public services and programs—referred to as “policymaking by other means” (Herd & Moynihan, 2018; Moynihan et al., 2016). Street-level bureaucrats may also impose such burdens to manage the public service gap—the disparity between their expected roles and the resources available to fulfill them (Hupe & Buffat, 2014; see also Brodkin & Majmundar, 2010; Tummers et al., 2015). Even in cases where decision-makers and public servants aim to maximize program participation, the administrative burden borne by citizens can deter them from accessing benefits (Daigneault & Macé, 2020).

The behavioral turn in public administration offers solutions to issues of unintended administrative burdens and non-take-up of benefits (Bertrand et al., 2006; Bhanot & Linos, 2020; Daigneault, 2025; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2017; Van Gestel et al., 2023; van de Walle et al., 2017). Decision-makers and scholars have increasingly drawn on psychological insights to influence individual behavior and improve policy compliance and outcomes (Gopalan & Pirog, 2017; Linos et al., 2020; Tummers, 2019; Weaver, 2015). Simple interventions from behavioral economics, known as nudges, are particularly promising. Thaler and Sunstein (2008) defined nudges as “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding options or significantly changing economic incentives. To count as a nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid” (p. 6). Nudges use cognitive mechanisms like priming, social norms, the spotlight effect, and anchoring to reduce administrative burdens and non-take-up. They include sending reminders, simplifying application processes, using default payment options, and reframing messages to emphasize collective benefits of online applications (Bhanot, 2020; Daigneault et al., 2012; John & Blume, 2017). Behavioral interventions are “quick, simple, cheap, and (perhaps most importantly) low-risk” (Bhanot & Linos, 2020, p. 169) as well as socially acceptable, making them likely to be adopted by public authorities. Beyond nudges (Hansen, 2019; Mertens et al., 2022), traditional microeconomic interventions such as information campaigns and rational persuasion also reduce administrative burdens. These methods are similarly simple, low-risk, and inexpensive, making them particularly suitable for addressing non-take-up that results from rational cost-benefit calculations (Bertrand et al., 2006).

However, determining the effectiveness of nudges and other simple behavioral interventions in increasing the take-up of social benefits is surprisingly difficult. First, while many behavioral studies focus on citizen–state interactions such as voter turn-out (e.g., Gerber & Tucker, 2024) or public recruitment (e.g., Bhanot & Heller, 2022; Linos et al., 2017), their findings are not necessarily transferable to the take-up of social benefits. Second, existing reviews on non-take-up discuss the issue based on selected sources, without systematically examining the impact of behavioral interventions (Currie, 2004; Daigneault, 2023; Daigneault et al., 2012; Eurofound, 2015; Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022). While some systematic reviews exist, they have examined program take-up only indirectly. For example, Halling and Bækgaard (2023) studied the relationship between administrative burden and take-up but discussed only one evaluation study on behavioral interventions. Similarly, the reviews by Szaszi et al. (2018) and Mertens et al. (2022) examined few studies on the effectiveness of nudges on the non-take-up of social benefits. Third, identifying field experiments across different settings and academic disciplines is challenging. Therefore, there is a pressing need to take stock of the evidence on the impact of behavioral interventions on non-take-up. Specifically, we must identify the most promising interventions for policymakers and public managers.

METHODS

How effective are nudges and other simple behavioral interventions at increasing the take-up of social benefits? This article addresses this question through a systematic review of the literature. We also aim to map the characteristics of published studies to take stock of scientific production on this theme, including identifying research gaps (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Ianniello et al., 2019; Van Dijck & Steen, 2023). To manage the ever-growing literature, we focused on journal articles, reports, and working papers published since 2005.1 The review process followed the PRISMA framework (Moher et al., 2009).

Search strategy

We used a comprehensive search strategy, recognizing that relevant studies span various disciplines (e.g., public administration, economics, social policy, social work), use related but distinct terms for take-up/non-take-up, and address diverse social benefits. An information specialist helped develop and execute the search strategy for electronic databases (see Appendix A2). We searched six electronic databases and Google Scholar, combining terms related to social benefits, take-up, and nudges/behavioral interventions and logical operators (AND, OR, NEAR).

Screening process

We imported 2,370 references into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovations), an online systematic review management tool. Two coders independently screened the references. They first reviewed titles and abstracts to exclude clearly irrelevant references, then assessed the full text of the remaining publications (see Appendix B). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

The definitive inclusion and exclusion criteria for full-text screening are listed in Appendix C. We focused on randomized field experiments, excluding natural and quasi-experiments (e.g., Dahan & Nisan, 2011) to identify the most rigorous evidence on intervention effectiveness (Hansen & Rieper, 2009; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). We also excluded studies lacking a standard control group, such as Hom et al. (2017) who evaluated pairs of interventions without a counterfactual scenario.3 Moreover, we tightened the programs and population criterion to exclude basic rights-based benefits (e.g., public pensions, unemployment insurance). We only included “minimal income protection,” which guarantees a social minimum (e.g., welfare/social assistance), and “tied benefits,” which do not (e.g., housing benefits, student financial aid; Bahle et al., 2010). These means-tested programs specifically target low-income individuals, who have the fewest resources and are the most affected by administrative burden and non-take-up (Bell et al., 2022; Heinrich, 2016; Herd et al., 2023). We also excluded studies focused on workfare programs (e.g., the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme; see Das et al., 2021) and those testing behavioral interventions in the context of institutional changes (e.g., Medicaid expansion; see Lanese et al., 2018). Finally, we excluded studies where the outcome variable was the timing of program take-up rather than its level, for instance Study 1 (Common Application) in Bird et al. (2019, 2021).

Data extraction

Coders performed data extraction independently in Covidence, reaching consensus through discussion. They used a standard grid, including study aims, design, methods, participants, setting (i.e., social program and country), interventions, control groups, outcome variables, results, statistical controls where applicable,4 and significance levels. They collected primary data on positive and negative outcomes for program application and/or program take-up in experimental and control groups. For multiple outcomes, we selected the most relevant variables.5 We calculated effect sizes, relative risk or risk ratios (RR), and confidence intervals, to compare findings across studies (Barratt et al., 2004). All effect sizes were calculated at the individual level, except for Page et al. (2020) and Avery et al. (2020), Study 2, which were at the school level. We contacted authors for clarifications and/or missing data when necessary.6

We documented details about the intervention medium (written documents, SMS, phone calls, in-person assistance). We prioritized the interventions’ descriptions in the appendix (when available) over those in the main publication because they are more precise and detailed.7 In composite interventions (i.e., combining multiple mediums), we distinguished between primary (X) and secondary or indirect (x) mediums, based on both the authors’ intentions and our evaluation of the intervention. Interventions were coded based on their focus (learning, compliance, psychological costs) and underlying mechanism(s). Using an inductive approach, we initially categorized interventions into four types: 1) providing information and/or changing its format (e.g., framing); 2) simplifying the application process (e.g., streamlined online application, simplified content, in-person assistance); 3) appealing to social norms, personal values or identities, or messenger trustworthiness (e.g., the tax credit rewards hard work); and 4) altering decision structures, promoting commitment and active decision-making to counter inertia (e.g., default options, self-imposed deadlines). These four simple categories helped us to organize the data in our sample.

Quality assessment

We used a slightly adapted version the PEDro scale (1999), to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. The PEDro scale is a validated tool (De Morton, 2009; Yamato et al., 2017) that was initially developed for physiotherapy. Whereas the PEDro scale measures some methodological practices that are less common in social sciences—for instance, blinding of the “therapists,” which in our case are instead referred to as treatment providers—it remains a useful tool to assess the risks of bias in primary studies. However, we removed item 4 (“the groups were most similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators”) because conducting balance tests on randomly assigned data was called into question in a recent study by Mutz et al. (2019), who noted that considering these tests can lead to erroneous conclusions.

Synthesis approach

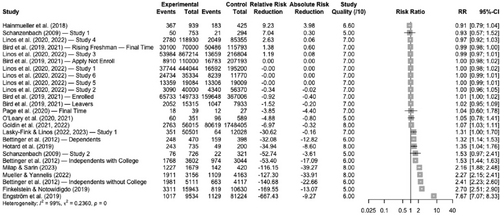

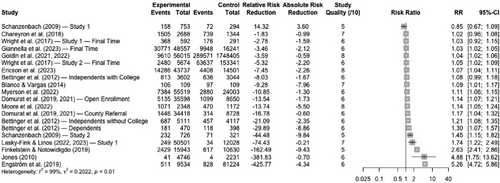

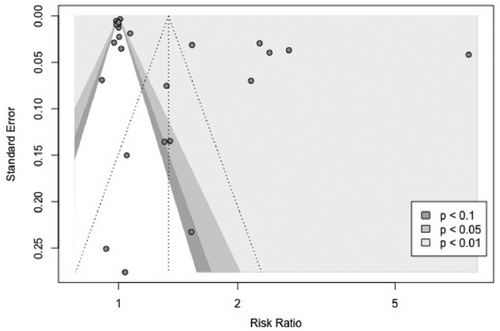

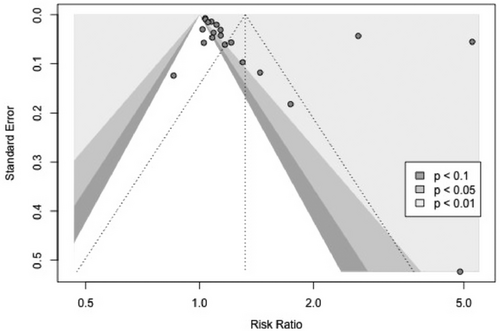

We employed two approaches to synthesize the results of the studies in our sample. First, forest plots illustrate the impact of interventions on program application or take-up. We did not include summary estimates of the pooled effect size (meta-analysis) due to the high heterogeneity in our sample (see the results section for discussion).

Second, we created thematic summaries, an alternative to meta-analysis (Kågesten et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2012). Unlike forest plots, we used the intervention, not the study, as the unit of analysis, including results derived from the same control group (e.g., Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, see n. 2). We used a slightly revised version of the inductive classification presented above for intervention mechanisms. Notably, appealing to norms, values, or identities is a type of framing. Other than their names, the other categories remained the same. We coded each intervention into four broad categories: providing information, framing information, providing assistance (including streamlining the process but excluding content simplification), and facilitating commitment, along with their combinations.8 While more complex classifications exist (Benish et al., 2023; Caraban et al., 2019; Mertens et al., 2022; Szaszi et al., 2018; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008), these four simple categories offer a comprehensive and detailed picture of the interventions in our sample for thematic summaries.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

We included 35 studies, identified with an asterisk (*) in the References section, and extracted data from them.8 A few observations stand out (see Table 3 at the end of this article). First, the field experiments included in this systematic review exhibit significant disparities in sample sizes, ranging from fewer than 100 to 1.8 million participants.

| Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Program and geographic location | Institutional partnership for implementing the field experiment | Sample | Description (treatment/experimental condition) | Intervention type | Cost type | Key findings related to program application and take-up |

| Avery et al. (2020, 2021) — Study 1 (National Study) | Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), US | College Board (private non-profit); uAspire, a non-profit organization focused on college affordability; and Signal Vine, a private for-profit text-messaging platform provider | 70,285 students from 745 public high schools primarily serving low-income students in 15 US states in the 2016 cohort (results aggregated at the school level) (Avery et al., 2021, p. 4) |

Intervention 1 — National Study Text message outreach by virtual advisors related to steps in the college-going process from the spring of junior year of high school through the summer after high school graduation. “The text message outreach provided reminders about college-going tasks and related deadlines along with the invitation to follow up with a counselor for additional guidance and support. […] the text outreach [was] coupled with virtual, text based advising as a stand-alone intervention” (Avery et al., 2021, p. 2) |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | No significant change in FAFSA completion (outcome measured at 7 different pts in time) |

| Avery et al. (2020, 2021) — Study 2 (Texas Study) | Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), TX, US | College Board (private non-profit); uAspire, a non-profit organization focused on college affordability; and Signal Vine, a private for-profit text-messaging platform provider | 21,001 students from 72 public high schools primarily serving low-income students in eight school districts in the Austin and Houston areas in the 2016 cohort (results aggregated at the school and student levels) (Avery et al., 2021, p. 2) |

Intervention 1 — Texas Study Text message outreach by virtual advisors related to steps in the college-going process from the spring of junior year of high school through the summer after high school graduation. “The text message outreach provided reminders about college-going tasks and related deadlines along with the invitation to follow up with a counselor for additional guidance and support. […] the text outreach [was] coupled with school counselor follow up support as integrated into the existing system of college going supports in one's own school.” (Avery et al., 2021, p. 2). |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance |

Increase in FAFSA completion at the school level from May onwards (8-10 pct. pts) Increase in FAFSA completion at the individual level from March onwards (4-5 pct. pts) No significant change in FAFSA completion at the school level before May or individual level before March |

| Bettinger et al. (2012) | Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), OH and NC | H&R Block (private, for-profit organization) | 788 high school seniors and recent graduates who are typically financially dependent on their parents, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1211) |

Intervention 1.1 — FAFSA Treatment (Simplication and Assistance with Aid Eligibility Information), Dependents A software and H&R Block professionals helped individuals complete the FAFSA. The “software first used individuals’ tax returns to answer about two-thirds of the questions on the FAFSA. Then, it led the H&R Block tax professional through an interview protocol to answer the remaining questions” (Bettinger, 2012, 1212). The software calculated individualized aid eligibility estimates and provided a written description of their aid eligibility and a list of the tuitions of four nearby colleges. Participants were “offered to have H&R Block submit the FAFSA electronically to the Department of Education (DOE) free of charge or send a completed paper FAFSA by mail so that individuals could submit it themselves. If not all information could not be collected, an external call center contacted the household to collect answers to remaining questions. FAFSAs were completed as much as possible and mailed to households with a prepaid envelope or filed directly with the DOE when applicants agreed” (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1213) |

Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

No significant change in federal student loan take-up Increase in FAFSA completion (16 pct. pts) Increase in Pell Grant reception (11 pct. pts) |

| 8,506 independent adults (nontraditional students) with no college degree, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1211) |

Intervention 1.2 — FAFSA Treatment (Simplification and Assistance with Aid Eligibility Information), Independents with No College Same as intervention 1.1 but different sample. |

Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

No significant change in federal student loan take-up Increase in FAFSA completion (27 pct. pts) Increase in Pell Grant reception (3 pct. pts) |

|||

| 6,129 independent adults (nontraditional students) with a college degree, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1211) |

Intervention 1.3 — FAFSA Treatment (Simplification and Assistance with Aid Eligibility Information), Independents with College Same as intervention 1.1 but different sample. |

Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psycho-logical |

Increase in FAFSA completion (20 pct. pts) No significant change in Pell Grant reception |

|||

| 478 high school seniors and recent graduates who are typically financially dependent on their parents, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1211) |

Intervention 2.1 — ‘Information-Only Treatment’ (Aid Eligibility Information), Dependents “For this group, we calculated individualized aid eligibility estimates using information from the tax return that the participant had just completed at the H&R Block office. We also gave individuals a written description of their aid eligibility and a list of the tuitions of four nearby colleges. To receive the aid amounts, the tax professional then encouraged individuals in this group to complete the FAFSA on their own (no help was given on the form as the emphasis for this group was only on providing information).” (Bettinger, 2012, p. 1213) |

Providing information | Learning |

No significant change in FAFSA completion No significant change in Pell Grant reception |

|||

| 4,839 independent adults (nontraditional students) with no college degree, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, 1211) |

Intervention 2.2 — ‘Information-Only Treatment’ (Aid Eligibility Information), Independents with No College Same as intervention 2.1 but different sample. |

Providing information | Learning | ||||

| 3,561 independent adults (nontraditional students) with a college degree, screened for FAFSA eligibility after completing their taxes in an H&R Block tax preparation office (Bettinger, 2012, 1211) |

Intervention 2.3 — ‘Information-Only Treatment’ (Aid Eligibility Information), Independents with College Same as intervention 2.1 but different sample. |

Providing information | Learning | ||||

| Bhargava & Manoli (2015) (2009 California Sample; short-term results for all participants; linked to Manoli & Turner (2014) — Study 2 below) | Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) CA, US | Internal Revenue Service (IRS) (public organization) | 3,058 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 1 — Simple Notice A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail. “While the initial notice was a textually dense, two-sided document that emphasized eligibility requirements repeated later in the worksheet, the new notice was single-sided, featured a larger and more readable font (Frutiger), a prominent headline, and did not repeat eligibility information” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3500) |

Framing information | Learning | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments |

| 3,589 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 2 — Simple Worksheet A simplified version of the official CP worksheet received months earlier by eligible persons was sent by mail. “[W]e redesigned the worksheet from the original CP notice by eliminating repetition, changing the font, and using a cleaner layout. The resulting single page worksheet (two-sided for those with dependents) carries a similar design aesthetic to the simplified notice” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3500–3501) |

Framing information | Learning; Compliance | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 3,679 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice |

Intervention 3 — Benefit Display (Low and High) A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail which prominently reported the upper bound of one's potential benefit in the headline, that is, “eligibility for a benefit “… of up to $457” in the case of no dependents and “… of up to $5,657” in the case of three or more dependents. In order to generate variation in the magnitude of perceived benefits, for subjects in this treatment with either one or two dependents, we additionally randomized the amount reported to either reflect the maximum dependent specific benefit (i.e., $3,043 for one dependent, and $5,028 for two dependents) or for the program as a whole (i.e., $5,657)” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3501) |

Framing information | Learning | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 3,069 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 4 — Transaction Cost Display (Low and High) A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail which provided varying guidance as to worksheet completion time: ““… less than 60[10] minutes” where the specific magnitude, (i.e., 60 or 10), was again randomized among those assigned to this treatment” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3501) |

Framing information | Learning; Compliance | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 4,814 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 5 — Indemnification Message A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail. In this version, a bold message on the worksheet indemnified respondents against penalties for unintentional errors: “Complete to the best of your ability—you will NOT be penalized for unintentional errors.” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3502) |

Framing information | Learning; Psychological | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 3,154 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 6 — Informational Flyer A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail which contained a one-page flyer with a trapezoidal benefit schedule. The flyer “displayed benefit information and marginal incentives through an annotated graphical display (customized by estimated number of dependents; figures are for single, as opposed to married, filers). […] The flyer also contained a section enumerating program “myths and realities” intended to clarify potentially confusing aspects of eligibility requirements (e.g., “I need to have a bank account to receive EIC benefits”)” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3502) |

Framing information | Learning | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 4,780 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 7 — Envelope Message A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail for which the envelope indicated “that the enclosed contents may benefit the recipient: “Important—Good News for You” […]. By IRS request, the treatment envelopes also included a parenthetical Spanish translation of the message.” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3502) |

Framing information | Learning | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 2,795 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 8 — Personal Stigma Reduction A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail which emphasized in its headline that the credit “was an earned consequence of hard work rather than a welfare transfer: “You may have earned a refund due to your many hours of employment.”” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3502) |

Framing information | Learning; Psychological | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| 2,786 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3498–3499) |

Intervention 9 — Social Stigma Reduction A simplified version of the official CP notice received months earlier was sent by mail which tackled social stigma in its headline “by invoking a, stigma-reducing, descriptive social norm: “Usually, four out of every five people claim their refund”” (Bhargava & Manoli, 2015, p. 3502) |

Framing information | Learning; Psychological | Estimates were not provided for this intervention only, but only for combinations of treatments | |||

| Bird et al. (2019, 2021) | Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), US | Large state public agency (public): sent text messages | 185,793 students “who graduated from high school in summer 2016 and applied to college using the state application portal for fall 2016” (Bird et al. 2021, p. 116) |

Intervention 1.1 — Large State Intervention, Rising Freshman A state agency sent six text messages spread through time “reminding students about steps they could take to apply for financial aid” (Bird et al. 2021, p. 117). Three combinations of variations were introduced in the intervention (analyzed jointly here): 1) information presentation (infographics vs. text); 2) variations in the timing of the message (early vs. on-time); 3) motivational framing activating a positive identity (motivated student) and highlighting the progress made by students and encouraging them to take the next steps. Text messages included a link to the FAFSA information portal as well as the possibility to receive tips through text messages, assistance through chat or a hotline. |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | No significant change in FAFSA completion |

| 317,193 students “who applied prior to Fall 2016 to college but who had not enrolled in school in the previous three years” (Bird et al. 2021, n. 5) |

Intervention 1.2 — Large State Intervention, Apply Not Enroll Same as intervention 1.1 but different sample. |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | No significant change in FAFSA completion | |||

| 516,739 “currently enrolled college students who had previously used the application portal” (Bird et al. 2021, n. 5) |

Intervention 1.3 — Large State Intervention, Enrolled Same as intervention 1.1 but different sample. |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | No significant change in FAFSA completion | |||

| 23,248 students “who had attempted 60 credits at a university or 30 credits at a community college and left without obtaining a degree” (Bird et al. 2021, n. 5) |

Intervention 1.4 — Large State Intervention, Leavers Same as intervention 1.1 but different sample. |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | No significant change in FAFSA completion | |||

| Blanco & Vargas (2014) | Emergency Humanitarian Help (Medical services, housing, household supplies, food), Colombia | Acción Social (AS) (public) | 218 internally displaced households that migrated to Bogotá over a 6-month period as per the Unique Registry of Displaced Population (RUPD) |

Text Message A concise text message (fitting in one text message) was sent informing the displaced household of their inclusion in the RUPD and asking them to go to the closest office (Attention and Orientation Unit) (Blanco & Vargas, 2014, p. 67) |

Providing information | Learning | No significant change in take-up of medical care, housing, supplies and food |

| Chareyron et al. (2018) |

Revenu de Solidarité Active (RSA or Solidarity Earned Income Supplement), département of Seine-et-Marne (metropolitan Paris area), France |

Conseil Général de Seine-et-Marne (General Council of Seine and Marne, public) | 4,032 “households from Seine-et-Marne that entered the RSA regime between October 2014 and March 2015” (Chareyron et al., 2018, p. 786) |

Intervention 1 — Simplified Mailing A letter written in such a way that the information it conveys is easier to understand, simpler and clearer than the standard letter was sent in order to reduce the intimidating effect and stress of the standard letter. The goal was to encourage beneficiaries to comply with the obligation to have an interview with a social worker. No information was added compared to the standard letter (Chareyron et al., 2018, p. 787) |

Framing information | Learning; Psychological | No significant change in take-up of RSA guidance interview |

|

Intervention 2 — Salient Information Mailing A letter highlighting the potential benefits of participating in the guidance interview […] By rendering the unexpected benefits more noticeable, it is designed to investigate whether this provision of supplemental information can play a role in inducing them to participate in the guidance interview. More specifically, the mailing highlights both features of the programs related to the receipt of the income benefit as well as the support measures that can facilitate the re-integration into the labour market […] It mentions that the beneficiary has a right to receive this free public transportation benefit [the FGT]. It also explicitly mentions that the beneficiary will be followed by a single case-worker (thus ensuring continuity of service) in order to develop an “action plan” involving counselling and/or vocational training tailored to his/her profile.’’ (Chareyron et al., 2018, p. 787–8) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning | No significant change in take-up of RSA guidance interview | ||||

| Domurat et al. (2019, 2021) |

Covered California, the state's health benefits exchange under the Affordable Care Act, CA, US |

Covered California (public organization) | 87,394 California “consumers that had an active determination of eligibility for Covered California 2016 coverage, but had not yet selected a plan. Consumers in this study entered the Funnel through two pathways” (Domurat et al., 2021, p.1554): open enrollment and county referrals |

Intervention 1 — Reminder Only/Basic Letter/Arm 2: Letter reporting “the open enrollment deadline, general benefits of insurance, and the Covered California website and telephone number where they could shop for plans” (Domurat et al., 2021, p. 1556) |

Providing information | Learning |

Increase in Covered California take-up in open enrollment (2 pct. pts) No significant change in Covered California take-up in county referral |

|

Intervention 2 — Subsidy/Subsidy and Penalty/Arm 3 Intervention 1 “…plus the household's estimated monthly subsidy and tax penalty, based on their reported income and household size.” (Domurat et al., 2021, p. 1556) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning |

Increase in Covered California take-up in open enrollment (2 pct. pts) Increase in Covered California take-up in county referral (1 pct. point) |

||||

|

Intervention 3 — Subsidy + Price/Price Compare/Arm 4 Interventions 1 and 2 “…plus a table listing the Silver and Bronze plans offered in their market, with their net-of-subsidy premium.” (Domurat et al., 2021, p. 1556) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning |

Increase in Covered California take-up in open enrollment (1 pct. point) Increase in Covered California take-up in county referral (1 pct. point) |

||||

|

Intervention 4 — Subsidy + Price + Qual/Price and Quality Compare/Arm 5 Intervention 3 “…but the table also included plans’ quality rating under the ACA's five-star quality rating system (QRS).” (Domurat et al., 2021, p. 1556) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning |

Increase in Covered California take-up in open enrollment (2 pct. pts) Increase in Covered California take-up in county referral (1 pct. point) |

||||

| Engström et al. (2019) |

Housing allowance for pensioners, Sweden |

Swedish Pensions Agency (public organization) | 90,758 “single pensioners […] with sufficiently low income to potentially qualify for the housing allowance drawn in May 2016” (Engström et al., 2019, p. 1354) |

Intervention 1 — Base Letter “The Base Letter informed that many pensioners who might be eligible for the housing allowance had not yet applied for it and that the recipient might be one of those. Furthermore, there was information on an income level for eligibility, where to apply, how the allowance is paid out and what it is. The letter also included a link to an online tool that pensioners can use to get a preliminary check of their eligibility status. The title of the Base Letter was “Have you heard about the housing allowance?”” (Engström et al., 2019, p. 1360). An application form was included. |

Providing information | Learning; Compliance |

Increase in housing allowance application (9 pct. pts) Increase in housing allowance take-up (4 pct. pts), but statistical significance unknown |

|

Intervention 2 — Myths Letter The Myths Letter had, in addition to the information provided in the Base Letter, information aiming to correct for four widespread myths about the housing allowance: The letter explained that the allowance does not depend on the type of housing (tenancy, condominium or own property) nor the value of the residence; that those with low income can have a certain wealth and still be eligible for the allowance; that those who share residence with others may be eligible; and that certain life changes that pertain to housing, income or marital status, might affect eligibility. The purpose of the Myths Letter was also to de-stigmatize the take-up of means-tested benefits. The title of this letter was: “280,000 pensioners receive housing allowance today—are you eligible, too?” (Engström et al., 2019, p. 1360). An application form was included. |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

Increase in housing allowance application (11 pct. pts) Increase in housing allowance take-up (5 pct. pts), but unknown statistical significance |

||||

|

Intervention 3 — Rule of Thumb Letter “The Rule of Thumb Letter showed, in addition to the information provided in the Base Letter, three examples of the possible level of allowance given three different. combinations of income and wealth. The purpose of this letter was to make the eligibility criteria with respect to income and wealth more transparent. An application form was included. […] The rules of thumb might help people overcome the rather complicated eligibility calculation.” (Engström et al., 2019, p. 1360–1361) An application form was included. |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance |

Increase in housing allowance application (9 pct. pts) Increase in housing allowance take-up (5 pct. pts), but unknown statistical significance |

||||

|

Intervention 4 — Table Letter “[T]he Table Letter showed nine potential combinations of income and wealth and the resulting housing allowance. Thus, this letter was similar in spirit to the Rule of Thumb Letter except that it included more detailed information on wealth and income criteria (and presented in table form)” (Engström et al., 2019, p. 1361). An application form was included. |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance |

Increase in housing allowance application (9 pct. pts) Increase in housing allowance take-up (4 pct. pts), but unknown statistical significance |

||||

| Ericson et al. (2023) | Massachusetts Health Connector, a state health insurance Marketplace under the Affordable Care Act, MA, US |

Massachusetts Health Connector (public organization) | 58,238 “non-elderly adults aged 18–64 in households where only one person was eligible for ConnectorCare” (Ericson et al., 2023, p. 6). Some individuals had “received an eligibility redetermination indicating that they were no longer eligible for Medicaid but were now eligible for ConnectorCare” (p. 5), and others “applied for coverage and were confirmed eligible for ConnectorCare, but had not completed the plan selection step” (p. 5) |

Intervention 1 — Generic Reminder Letter (Arm 2) “Individuals were sent letters via postal mail that reminded them of their eligibility for ConnectorCare insurance and provided information about how to apply for coverage. These letters did not contain any personalized information.” (Ericson et al., 2023, p. 6) |

Providing information | Learning | Increase in ConnectorCare take-up (1 pct. point) |

|

Intervention 2 — Personalized Information Letter (Arm 3) Intervention 1 “…but with the addition of a table with personalized after-subsidy premium costs for each of their plan options.” (Ericson et al., 2023, p. 6) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning | Increase in ConnectorCare take-up (2 pct. pts) | ||||

|

Intervention 3 — Streamlined-Enrollment (“Check-the-Box”) Letter (Arm 4) Letter similar to intervention 2 “but which also allowed them to enroll by simply checking a box for their selected plan and sending back the form in a pre-paid envelope.” (Ericson et al., 2023, p. 6) |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | Increase in ConnectorCare take-up (3 pct. pts) | ||||

| Finkelstein & Notowidigdo (2019) | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), PA, US | Benefits Data Trust (BDT) (private nonprofit organization) and Pennsylvania's Department of Human Services (DHS) (public organization) |

15,945 “elderly individuals in Pennsylvania who are on Medicaid, and therefore likely eligible for SNAP, but not currently enrolled in SNAP” (Finkelstein & Notowidigdo, 2019, p. 1552) . |

Intervention 1 — Information plus Assistance “The information component consists of proactively reaching out by mail to individuals whom they have identified as likely eligible for SNAP and following up with a postcard after eight weeks if the individual has not called BDT. Letters and postcards inform individuals of their likely SNAP eligibility […] and typical benefits […] and provide information on how to apply […] offering a number at BDT to call […] These materials are written in simple, clear language for a fourth- to sixth-grade reading level […] The assistance component begins if, in response to these outreach materials, the person calls the BDT number. BDT then provides assistance with the application process. This includes asking questions so that BDT staff can populate an application and submit it on their behalf, advising on what documents the person needs to submit, offering to review and submit documents on their behalf, and assisting with postsubmission requests or questions from the state regarding the application. BDT also tries to ensure that the individual receives the maximum benefit for which they are eligible by collecting detailed information on income and expenses (the latter contributing to potential deductions)” (Finkelstein & Notowidigdo, 2019, p. 1521–1522). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

Increase in SNAP application (16 pct. pts) Increase in SNAP take-up (12 pct. pts) |

|

Intervention 2 — Information Only The “Information Only intervention contains only the letters and follow up postcards to nonrespondents sent as part of the outreach materials. They are designed to be as similar as possible to the information content of the Information Plus Assistance intervention: both are sent from the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (DHS) and include virtually identical language and layout. Some minor differences were naturally unavoidable” (Finkelstein & Notowidigdo, 2019, pp. 1522–23). |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

Increase in SNAP application (7 pct. pts) Increase in SNAP take-up (5 pct. pts) |

||||

| Giannella et al. (2023) | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)/ CalFresh, Los Angeles County, Ca, US | Los Angeles County and Department of Public Social Services (public organization) | 64,798 “Los Angeles County SNAP applicants. [The] sample includes all cases that applied to the program through GetCalFresh.org, an online application system which receives more than half of the SNAP applications in Los Angeles” (Giannella et al., 2023, p. 1) |

Alternative Interview Process/Flexible Interview through the “End-to-End” (E2E) Call Line “All applicants, regardless of experimental group, were assigned a scheduled interview date through the standard process. Modified communication provided applicants with information on how to contact the ‘end-to-end’ (E2E) line to complete their interview. Applicants could call this number at their convenience and connect directly to a caseworker to complete their interview. Treatment group members who did not call the E2E line by their scheduled interview date were contacted by the county for an interview through the standard channels.” (Giannella et al., 2023, p. 1–2) |

Providing assistance | Compliance |

Increase in SNAP take-up after 5 days (14 pct. pts) Increase in SNAP take-up after 150 days (2 pct. pts) Increases in SNAP take-up at various pts in time between 5 and 150 days (decreasing increases with time) |

| Goldin et al. (2021, 2022) | Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC), US | Internal Revenue Service (IRS) (public organization) | 1,804,420 taxpayers “drawn from a random 10% sample of all taxpayers who did not file a tax return for the prior tax year (2017), but who […] appeared to have 2017 income above zero and below $55,000 - the maximum threshold to qualify for free assistance through both Free File and VITA. […] we restricted the sample to individuals who lived within 30 miles of at least two VITA sites. […] because the intervention could not have affected their behavior, we excluded from the sample individuals who filed a 2018 tax return before the experimental letters were sent (i.e., returns posted to the IRS database prior to mid-March, 2019).” (Goldin et al., 2022, p. 3) |

Letter from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) “A one-time letter from the IRS was addressed to the taxpayer. […] The letter contained information about free tax preparation programs – either Free File, VITA, or both – including a description of the program, benefits of assisted preparation, eligibility criteria and information on how to access the program. The language used to describe the documents taxpayers were required to provide was drawn from the Free File and VITA websites. The letters were designed to highlight the likely eligibility of the specific recipient (“According to our records, you may qualify”) as well as the broad eligibility of the program (“Two out of three taxpayers qualify”).” (Goldin et al., 2022, p. 3–4) |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | Increase in EITC application (0.3 pct. point) |

| No significant change in CTC application (0.2 pct. point) | |||||||

| Increase in tax return filings with a refunding claim (0.6 pct. point) | |||||||

| Hainmueller et al. (2018) |

Public/private naturalization program organized by the New York State Office for New Americans (ONA) NY, US |

New York State Office for New Americans (public organization) and Opportunity Centers (OCs), community-based organizations contracted by the Office for New Americans | 1,347 “immigrants who were interested in naturalization and registered for the public/private naturalization program online, by phone, or in person during the registration window between July and September 2016” (Hainmueller et al., 2018, p. 947) |

Intervention 1 — Letter A English- or Spanish-language letter was sent from the Office for New Americans reminding registrants of their potential fee waiver eligibility. |

Providing information | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | No significant change in applications for naturalization |

|

Intervention 2 — Letter + Metro Card Intervention 1 plus a $10 MetroCard to travel to an Opportunity Center. |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 3 — Letter + Text Messages Intervention 1 plus four text SMS reminders (one per week over four weeks) were then sent in English or Spanish. In addition to a link to a website, the SMS contained encouragements such as ‘Applying for citizenship is easier than you think’. |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 4 — Call and Appointment A call was made from Opportunity Center (OC) to schedule an in-person appointment with an attorney. |

Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | |||||

|

Intervention 5 — Mixed Outreach Strategy A call was made from Opportunity Center (OC) to schedule an in-person appointment with an attorney. Then, up to four telephone reminders were sent by staff. An email or letter contact was made if the phone contact failed. A $10 MetroCard to travel to an Opportunity Center conditional on appointment attendance was also joined. |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | |||||

| Hotard et al. (2019) |

Public/private naturalization program organized by the New York State Office for New Americans (ONA) NY, US, and Federal Fee Waiver |

New York State Office for New Americans (public organization) | 935 fee-waiver-eligible registrants: “immigrants in New York City that were over 18 years old registered online for the state sponsored program to receive assistance with their naturalization application. All participants were screened as being eligible to naturalize, live in New York State, and were screened as being eligible for the federal fee waiver.” (Hotard et al., 2019, reporting Summary, p. 2) |

Fee Waiver Notice At the end of the registration process, the final online registration screen “stated that participants were probably eligible for the federal fee waiver program The prompt also provided a link to a resource webpage where they could learn about naturalization and find a nearby immigrant service provider that could assist them with their application.” (Hotard et al., 2019, p. 679) |

Providing information | Learning; Compliance | Increase in applications for naturalization (9 pct. pts) |

| Jones (2010) | Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), US | Private, for-profit organization: “a large-scale, nationwide firm in the retail sector” (Jones, 2010, p. 151) | 6,977 low-income workers from the private sector who were eligible for the EITC |

Intervention 1 — Advance EITC Only Treatment Employees were provided with ‘‘a color flier and short video presentation, encouraging them to sign up for the Advance. The fliers tell employees that they may increase their take-home pay by signing up for the Advance and receiving the EITC earlier. The flier also explains the eligibility requirements, the procedure for enrolling in the program, and additional details […] In addition, these employees are given the IRS W-5 form needed to begin Advance payments. […] I train managers either in person or over conference calls, and also provide information packets to aid in determining the eligibility of employees. Managers distribute the Advance EITC information during routine group meetings. Those employees who are both interested and eligible can then sign up for the program at their work site. […] Employees are given a soft deadline of two weeks to hand in a form indicating their preference, even if they are not interested in the program. The deadline forces procrastinators to hand in paperwork. Both employees who select the Advance option and those who decline must submit a form. This makes it harder to infer who is enrolling in the program and reduces a stigma effect. (Jones et al., 2010, p. 152) |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance; Facilitating commitment | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | No significant change in EITC take-up |

|

Intervention 2 — Advance EITC and 401(k) Treatment Same as intervention 1 (above), but employees also received ‘‘informational materials [suggesting] that additional payment received from the Advance EITC may be channeled into a 401(k) plan. They are told via a video presentation, “now you can take the extra $30 per week from the Advance EITC and put it into your 401(k) plan. Managers are given an additional table outlining the 401(k) contribution level needed to roughly offset Advance payments. In addition to Advance EITC forms, the employees also receive the necessary forms for 401(k) enrollment […and] are likewise subject to a soft deadline of two weeks in which to make a decision. If individuals believe that they lack the discipline to receive Advance payments with their paycheck, they can use 401(k) contributions to automatically put the funds toward retirement. However, if individuals only wish to put the money away for a short period of time, then the 401(k) account may prove too illiquid. Therefore, this test only addresses a forced savings motive that includes long-term savings goals” (Jones et al., 2010, p. 152–153) |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance; Facilitating commitment | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | Increase in EITC take-up (1 pct. point) | ||||

| Lasky-Fink & Linos (2022, 2024) — Study 1 (Denver Study) | Emergency rental assistance (ERA) program, CO, US |

Denver County's Department of Housing Stability and Office of Social Equity and Innovation (public organization) |

62,529 renter households eligible to the County's temporary rental assistance program |

Intervention 1 — Information Only “Renters […] were sent a postcard that provided clear and simple information about Denver County's rental assistance program and instructions for applying. […] All information was provided in English and Spanish, and language aligned with the County's status quo communications.” (Lasky-Fink & Linos, 2024, p. 273) |

Providing information | Learning; Compliance |

No significant change in application to the Denver County's temporary rental (housing) assistance program Increase of take-up of the Denver County's temporary rental (housing) assistance program (0.2 pct. point) |

|

Intervention 2 — Information + Stigma Intervention 1 “…but with subtle language changes to target potential sources of anticipated and internalized stigma associated with program participation” (Lasky-Fink & Linos, 2024, p. 273) |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Compliance; Psychological |

Increase in application to the Denver County's temporary rental (housing) assistance program (0.2 pct. point) Increase of take-up of the Denver County's temporary rental (housing) assistance program (0.2 pct. point) |

||||

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 1 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 639,244 low-income potentially EITC eligible households from California who did not claim it |

Basic Informational Message + Link “Text messages were sent manually by GSO volunteers in March and April 2018, with observations sequenced randomly. Texts informed recipients of their potential eligibility and of the need to file a return in order to claim the credit and included a link with more information to reduce learning costs.” (Linos et al., 2022, p. 441) |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning | No significant change in the federal EITC application |

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 2 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 96,370 low-income potentially EITC eligible households from California who did not claim it |

Intervention 1 — FTB Formal “There were four treatment arms, delivered as different letters, that addressed learning costs and psychological costs related to potential mistrust of the messenger or message. Letters varied in two dimensions that both addressed source credibility: the source (GSO or FTB) and the formality. Each sender's letters used the relevant logos, signatures, and return addresses. In addition, half were structured as formal letters and half as informal flyers. The front of each letter was printed in English; the back contained the same information in Spanish.” (Linos et al., 2022, p. 441). Intervention 1 was a letter sent from the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) (source credibility = government messenger) structured as a formal letter (high level of formality) |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |

|

Intervention 2 — FTB Informal Intervention 2 was a letter sent from the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) (source credibility = government messenger) structured as an informal flyer (low level of formality) which used social marketing strategies such as injunction in color and large font size: ‘Claim your refund!’ (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 3 — GSO Formal Intervention 3 was a letter sent from the Golden State Opportunity Foundation (GSO) (source credibility = NGO) as a formal letter (high level of formality). (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 4 — GSO Informal Intervention 4 was a letter sent from the Golden State Opportunity Foundation (GSO) (source credibility = NGO). The informal letter used social marketing strategies such as injunction in color and large font size: ‘Claim your refund!’ (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 3 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 1,084,018 low-income potentially EITC eligible households from California who did not claim it |

Intervention 1 — Basic Info “There were four treatment arms, each consisting of a single text message. To target learning costs, each message informed recipients about potential eligibility and the need to file taxes to claim the credit. Treatment arms 2 and 3 also targeted compliance costs by offering assistance through a hotline or via text, respectively. Treatment arm 4 included additional information on the average benefit amount to further address learning costs.” (Linos et al., 2022, p. 441). Intervention 1 was a text message sent by a volunteer of the Golden State Opportunity Foundation informing recipients about potential eligibility and the need to file taxes to claim the credit and providing a link to a website for more information about eligibility. |

Providing information | Learning | |

|

Intervention 2 — 211 Info Same text as intervention 1 plus a local hotline phone number for assisting them in applying to the program (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | |||||

|

Intervention 3 — Text-Based Assistance Offered Same text as intervention 1 plus text-based assistance for applying to the program, if needed (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | |||||

|

Intervention 4 — Benefit Value Intervention 4 combined intervention 1 and 3, but “…included additional information on the average benefit amount to further address learning costs.” (Linos et al., 2022, p. 441). The text mentioned ‘Eligible families got back an average of $2,000 last year’ (see interventions 1 and 3 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 4 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 204,285 low-income potentially EITC eligible households from California who did not claim it and had not filed taxes in the past three years |

Intervention 1 — Simple Letter, Formal “There were eight treatment arms, delivered as different letters. […] Letters came from the FTB and contained one of four different messages: a simple message about the credit; a simple message that also included information about the average value of the credit (addressing learning costs); a message that added information about the location, hours, and contact information of the nearest in-person free tax preparation assistance site (addressing compliance costs); and a message that included both the average value of the credit and tax assistance information. Each message was delivered in a formal and an informal version, with the idea that formal letters might signal more source credibility (addressing psychological costs). The front of each letter was printed in English; the back contained the same information in Spanish. In addition, each letter contained a URL at which recipients could find the letter translated into Korean, Vietnamese, Chinese, or Russian.” (Linos et al., 2022, pp. 441–442). Intervention 1 is a letter sent from the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) structured as a formal letter (high level of formality). |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Psychological | |

|

Intervention 2 — Formal Letter, Credit Amount Intervention 1, but the letter included the average amount received by participant (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 3 — Formal Letter and VITA Intervention 1 but the letter included detailed information about the location, hours, and contact information of the nearest in-person free tax preparation assistance site (Volunteer Income Tax Assistance or VITA). (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 4 — Formal Letter, Credit Amount and VITA Intervention 4 combined intervention 2 and 3 (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 5 — Simple Letter, Informal Letter similar to intervention 1, but informal (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 6 — Informal Letter, Credit Amount Letter similar to intervention 2, but informal (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information | Learning; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 7 — Informal Letter, VITA Letter similar to intervention 3, but informal (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 8 — Informal Letter, Credit Amount and VITA Intervention 8 combined intervention 6 and 7 (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 5 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 38,093 low-income potentially EITC eligible households from California who did not claim it and who participate in the CalFresh program |

Sequence of Text Messages “All treated individuals received the same sequence of text messages, designed to address both learning and compliance costs. The first message included a personalized benefit amount estimated using the recipients’ household composition and quarterly earnings data. […] If the recipient texted “1” for more information, they were provided the URL to an online free tax-preparation software. If they responded “1” again, they were provided the address and hours of the closest Volunteer Income Tax Assistance or VITA site to the client's 9 digit zip code. When that site required appointments, the text also included a link for registration. Texts were sent in English or Spanish, depending on the language indicated in the CalFresh record” (Linos et al, 2022, p. 442) |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance | |

| Linos et al. (2020, 2022) — Study 6 | Federal and California Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), CA, U.S. (only the federal EITC is analyzed here) | California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS (public organizations) and a private, not-for-profit organization, Golden State Opportunity (GSO) receiving funding from the state | 47,104 potential EITC eligible claimers who did not claim it and who participate in the CalFresh program |

Intervention 1 — Basic Text “There were three treatment arms, each delivered by text message. The first treatment arm was a simple text, informing recipients of their potential eligibility, and provided a URL to calculate their credit and a hotline to learn where to file for free. The second treatment arm provided the same information as the first text, along with the average benefit amount. The third treatment arm, as in Study 5, included a personalized credit amount. The three treatments did progressively more to address learning costs. Moreover, the fact that they came from the local CalFresh program should have increased source credibility and reduced psychological costs. Texts were delivered in March 2019 in the language indicated in the recipient's CalFresh record: English, Spanish, Chinese, or Vietnamese. Speakers of other languages received the English message.” (Linos et al, 2022, p. 541). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |

|

Intervention 2 — Average Benefit Intervention 1 but the average benefit amount was also provided (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

|

Intervention 3 — Personalized Benefit Intervention 1 but the personalized benefit amount was also provided (see also intervention 1 above). |

Providing information; Framing information; Providing assistance | Learning; Compliance; Psychological | |||||

| Manoli & Turner (2014) — Study 2 (2009 California Sample; medium-term results by type of participants; linked to Bhargava & Manoli (2015) — Study 1 above) | Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) CA, US | Internal Revenue Service (IRS) (public organization) | 75,107 individuals from California who filed a tax return for tax year 2009 but failed to claim an EITC credit and satisfied a set of eligibility screens that resulted in the receipt of a CP09 (with dependents) or CP27 (without dependents), and who did not respond to this CP notice |

Intervention 1 — Simplified Notice ‘‘Simplified notices which aimed to reduce complexity by clarifying eligibility conditions and making response worksheets shorter and easier to read. […] The simple notice headline was “You may be eligible for a refund” (Manoli & Turner, 2014, pp. 9–10 and n. 15) (see also Intervention 1 — Simple Notice in Bhargava & Manoli, 2015) |

Framing information | Learning |

No significant change in EITC application in returns without kids and returns with kids No significant change in EITC take-up in returns without kids and returns with kids |

|

Intervention 2 — Benefit Notice ‘‘Benefit notices which aimed to increase the salience of maximum credit amounts. […] the benefit notice headline was “You may be eligible for a refund up to $5,657” (Manoli & Turner, 2014, p. 10 and n. 15) (see also Intervention 3 — Benefit Display (low and high) in Bhargava & Manoli, 2015) |

Framing information | Learning |

Decrease in EITC application in returns without kids (-19 pct. pts) and returns with kids (-5 pct. pts) Decrease in EITC take-up in returns without kids (-37 pct. pts) and returns with kids (-53 pct. pts) |

||||

|

Intervention 3 — Social Influence Notice ‘‘Social influence notices which aimed to use information on peer take-up to influence responses. […] the social influence notice was “You may be eligible for a refund. Usually, 4 out of every 5 people claim their refunds” (Manoli & Turner, 2014, p. 10 and n. 15) (see also Intervention 9 — Social stigma reduction in Bhargava & Manoli, 2015) |

Framing information | Learning; Psychological |

Increase in EITC application in returns without kids (17 pct. pts) Increase in EITC take-up in returns without kids (8 pct. pts) No significant change in EITC application or take-up in returns with kids |

||||

|

Intervention 4 — Claiming Time ‘‘Claiming time notices which aimed to reduce perceptions of the necessary time to respond to the notices. […] the claiming time notice headline was “You may be eligible for a refund. Claiming your refund usually takes less than 10 minutes.” (Manoli & Turner, 2014, p. 10 and n. 15) (Intervention 4 — Transaction cost display (low and high) in Bhargava & Manoli, 2015) |

Framing information | Learning; Compliance |